Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant shift to virtual resident education. While novel methods for virtual resident training have been described, many of these demonstrate a substantial change from previous instructional methods and their efficacy cannot be directly compared to in-person teaching. We sought to determine if the conversion of our intern “summer school” from an in-person to online format (a) impacted the knowledge acquisition of interns, and (b) their preferences for senior resident-led didactics.

DESIGN

A senior-resident led intern summer curriculum was started in an in-person format with the 2019-2020 academic year. Interns underwent assessments of their knowledge and surveys of changes in subject confidence. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the curriculum was shifted to an online format for the academic year 2020-2021.

SETTING

Washington University in St. Louis, an academic medical center located in St. Louis, Missouri

PARTICIPANTS

PGY1 general surgery residents during academic year 2019-2020 (n = 13) and 2020-2021 (n = 14).

RESULTS

In both years, interns demonstrated significant increases in confidence pre- and post-summer school in all domains (p <0.01). This was no different between the in-person and the virtual administration of the bootcamp (p 0.76). In both virtual and in-person curricula, interns demonstrated increased knowledge as measured by multiple choice, boards-style question quizzes. There were no significant differences between virtual and in-person formats. In both formats, interns reported a preference for senior residents as teachers (81% v. 77%) and increased comfort in asking questions in senior resident-led vs. attending-led didactics (91% v 100%).

CONCLUSION

Virtual senior-resident led intern educational sessions are equally as effective as in-person sessions for knowledge acquisition and improving confidence in intern-specific domains. In both virtual and in-person settings, interns prefer senior resident teachers to attendings. Virtual senior resident-led education is an effective and simple method for intern instruction, regardless of the format/approach.

KEY WORDS: surgical education, virtual education, intern “bootcamp”

COMPETENCIES: Medical Knowledge, Patient Care

INTRODUCTION

Interns are required to absorb a vast amount of information within the first few weeks of their transition into residency from medical school. To ease this transition, many surgical residencies have instituted intern “bootcamps”.1 These transitional education sessions have previously been demonstrated to improve intern confidence in technical skills,2 medical knowledge,3 and overall preparation for surgical residency.4 Additionally, intern bootcamps have been demonstrated to correlate with PGY-1 level clinical performance.5 Generally, these bootcamps are led by attending surgeons or medical school faculty. However, significant research has also been generated to demonstrate the strength of resident-led education.6 , 7 A senior resident-led intern bootcamp can result in increased interactions between junior and senior surgical residents, which may improve intern comfort working with senior residents outside of the classroom. Greater team dynamics due to comfort of junior team members has been linked to improved patient outcomes.8 Based on these findings, we implemented a senior resident-led intern summer school, called “Transition to Internship and Education in Surgery ” (TIES), for the last several years at our institution with the intention of improving junior surgical resident knowledge, patient care, confidence, and interaction with senior surgical residents.

Given the prior success of this resident-led curriculum, we were concerned about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on our ability to maintain the improvements in confidence and knowledge of junior surgical learners after summer school education. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a rapid change in the structure of surgical education. Due to the need for social distancing, many previously in-person surgical education activities have been shifted into a virtual format.9, 10, 11 This change has necessitated the rapid adaptation of learners and educators. While there are benefits to the shift to online learning including the ability to safely reach an increased number of learners,12 the effects of this shift are still undergoing investigation. Modified didactic,13 surgical skills,14 , 15 and mock oral board examination16 curricula were enacted at multiple centers demonstrating feasibility and resident satisfaction. Many educational formats have required significant restructuring in order to convert to a virtual setting, and thus direct comparison to the outcomes of previous, in-person formats is limited and the effectiveness of these new formats is not well understood.17

Direct comparison between online and in-person learning can provide important information about the effects of virtual learning on surgical education. Without the ability to directly compare in-person and virtual events, we are unable to determine the effects of virtual learning on knowledge uptake and learner educational preferences. Because of the prior success of our TIES curriculum, during the 2020 academic year, we sought to maintain the best aspects of this curriculum in a virtual environment. Here, we describe the direct comparison of our intern boot camp before and after the shift to online learning. We hypothesized that the transition to a virtual environment might result in a negative impact on our curriculum. As such, the aim of our work was to investigate the effects of virtual learning on surgical intern knowledge uptake and preferences regarding instructional methods and instructors.

METHODS

Bootcamp Curriculum Design

The TIES curriculum included didactic sessions covering important topics identified by prior needs analysis. Senior residents and key faculty were identified and included in focus groups to determine the appropriate topics which are important to the ability of interns to manage patients. Prior to beginning the TIES curriculum, interns participated in a two-week orientation that has been in place for many years at our program. In both academic years in this study, interns received curricular training on essential knowledge for success as an intern including training on how to answer common calls, management of common issues with surgical drains and lines, and management of intensive care unit (ICU) level patients. A summary of these topics and the curricular delivery format used in each year can be found in Table 1 . Additional non-knowledge-based topics were covered in this curriculum, including lectures on study methods during surgical residency, wellness, and use of the electronic medical record (EMR). The results of these latter areas were not surveyed or tested for this study.

Table 1.

Curricular Comparison Between In-Person and Virtual Formats

| 2019-2020 In-Person Curriculum | 2020-2021 Virtual Curriculum | |

|---|---|---|

| Common Calls | Instruction: Small group interactive sessions Evaluation: Quiz |

Instruction: Small group virtual interactive sessions Evaluation: REDCap Survey |

| Tubes and Drains | Instruction: Large group case-based lecture Evaluation: Quiz |

Instruction: Virtual case-based lecture Evaluation: REDCap survey |

| ICU Care | Instruction: Large group case-based lecture Evaluation: Quiz |

Instruction: Virtual case-based lecture Evaluation: REDCap survey |

Both categorical and preliminary general surgery residents were included in our study. Local institutional review board (IRB) research approval was obtained. All participants consented to participation in the study in both academic years and data were collected according to IRB protocol.

Lectures

All TIES didactic lectures were provided by senior surgical residents with interest in surgical education who received preparation regarding curricular goals and assessment metrics. Goals and objectives for each lecture were identified by discussion between key senior residents and faculty, as well as review of the Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE) curriculum objectives for each topic.18 The SCORE modules identified as relevant for each topic have been included in the supplemental materials (Supplemental Materials 1).

Senior surgical residents developed their own lecture materials including images, PowerPoint slides, and other tools. Each lecture occurred during protected didactic time over seven subsequent weeks during July and August and took one hour, each for a total of seven hours of additional instruction.

Quiz Development

After review of each senior resident's lecture and review of the SCORE objectives for each topic, quiz questions were generated. These were randomly assigned into pre- and post-lecture quizzes by random number generator to prevent bias of question assignment. Senior residents were provided the pre- and post-lecture quizzes to review before their lecture. Not all lecture topics included knowledge assessment.

Survey Development

Pre-curriculum and post-curriculum surveys were developed to gauge each intern's confidence levels and areas of weakness. Interns were asked to rate their confidence on a Likert scale from 1 (no confidence) to 5 (full confidence). Interns were provided with identical questions to rate their confidence after completion of the two-month curriculum. Additionally, interns were asked to rate their satisfaction with the education they received during each lecture on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). At the end of the curriculum, interns were additionally asked to rate their preferences regarding senior resident or attending surgeon instruction, their comfort participating in these sessions, and their comfort interacting with senior residents. During in-person iterations of the curriculum, these surveys were distributed on paper and entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database (version 9) hosted at Washington University in St. Louis. During virtual iterations of the curriculum, interns received survey links by email to directly enter their survey results into REDCap.

Online Reformatting

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing requirements necessitated the conversion of our previously delivered curricula to an online format (Table 1). All online lectures were given using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, version 5). Small group sessions occurred using the breakout function of zoom. Pre- and post-lecture quizzes were converted to REDCap surveys using identical questions to the in-person sessions to allow for direct comparison. Resident teachers were already familiar with zoom functionality and received no additional training in online teaching methodology. In all but one case, lecture (ICU Care) the lecturer was the same during both years. Lecture topics, format, objectives, and design was maintained as similarly as possible to the in-person curricular delivery in order to allow for direct comparison between in-person and virtual iterations of the curriculum.

Statistical Evaluation

Graphpad (version 8.4, San Diego, CA) was used for data analysis and figure development. Changes in confidence were determined as the difference between the post-curricular confidence rating and the pre-curricular confidence rating. Data is expressed as the median score +/- standard deviation. Descriptive statistics were evaluated to examine intern preferences regarding teaching. Confidence scores and lecture ratings were compared using Mann-Whitney U testing for non-parametric, ordinal data. Quiz scores were evaluated by Student's t-test for paired data. In all cases, a p value <0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Confidence in Completing Essential Skills

A total of 27 categorical and preliminary general surgery interns completed our TIES curriculum over two academic years (AY 2019-2020 n = 13, AY 2020-2021 n = 14).

We assessed intern confidence regarding curricular objectives on a Likert scale from one (no confidence) to five (full confidence). When considering the changes between pre-curricular confidence and post-curricular confidence, no significant difference in the change in confidence was noted between in-person and virtual curricula in topics evaluated: common calls (mean change 1.3 v 1.8, p 0.34), managing surgical drains and lines (0.9 v. 1.6 p 0.07), and care of ICU patients (1.2 v 1.2, p 0.89) (Fig. 1 ).

FIGURE 1.

Virtual and In Person Bootcamp Curricula are an Effective Method for Increasing Intern confidence in Completing Essential Skills Across both academic years, interns demonstrated similar increases in confidence in all domains.

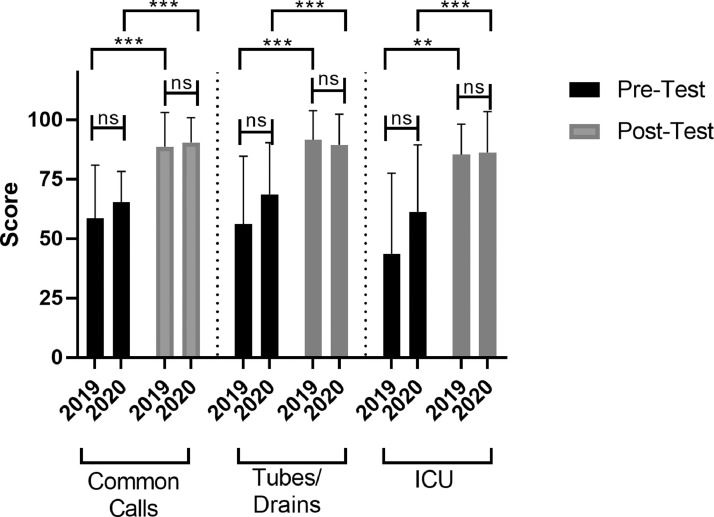

Knowledge Acquisition

To determine the efficacy of our curriculum, interns completed pre- and post-lecture quizzes focused on lecture objectives. In both in-person and virtual formats, interns demonstrated significant knowledge acquisition in all sessions (Fig. 2 ). In the in-person curricula (AY 19-20), interns demonstrated significant gains in mean quiz scores for all sessions. Common calls mean quiz scores increased from 58.6% to 88.8% (p <0.01), tubes and drains mean quiz scores increased from 56.3% to 91.7% (p < 0.01), and care of ICU patients quiz scores increased from 43.7% to 61.4% (p < 0.01). Very similar trends were seen in the virtual iteration of the curriculum with mean quiz scores increasing significantly in all curricular sessions. In the virtual setting, the common calls quiz scores increased from 65.5% to 90.5% (p < 0.01), tubes and drains scores 68.8% to 89.6% (p <0.01), and ICU scores from 61.3% to 86.4% (p 0.02). There were no significant differences between the pre- and post-session quiz scores between the two academic years.

FIGURE 2.

Virtual and In Person Bootcamp Curricula are Equally as Effective in Knowledge Acquisition. In both in-person and virtual iterations of our curriculum, interns demonstrated statistically significant increases in knowledge of tested domains. No significant differences were noted in pre-test and post-test scores between academic years.

Senior Residents as Teachers

After completion of the TIES curriculum, interns were surveyed regarding their preferences for who provided their instruction. All sessions in the TIES curriculum were led by senior residents. In both in-person and virtual formats, interns expressed preference for senior residents over attendings as teachers for the summer school sessions with 81.8% and 76.9% preferring senior resident teachers, respectively (Fig. 3 a). Interns were also asked if senior resident-led sessions increased their comfort interacting with senior residents. In both in-person and virtual settings, similar percentages of interns reported increased comfort interacting with senior residents (81.1% vs 84.6%) (Fig. 3b). Finally, interns reported their comfort asking questions during these senior resident-led sessions as compared to their comfort asking questions in traditional attending-led didactic sessions. In both in-person and virtual formats, the vast majority of interns reported they were more comfortable (91.1% v. 100%) asking questions in TIES sessions as compared to traditional large group, attending-led didactics (Fig. 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Residents Express the Preference for Senior Resident Teachers Regardless of Curricular Delivery Method. (a) No change in preference for senior resident teachers was noted between in-person (81.8%) and virtual (76.9%) versions of the curriculum (b) Interns were equally likely to report increased comfort interacting with senior residents after in-person (81.1%) and virtual (84.6%) versions of the curriculum (c) Interns reported similar increases in comfort asking questions in these sessions between in-person (91.9%) and virtual (100%) curricula

Lecture Satisfaction: In-Person versus Virtual

At conclusion of each summer school lecture, interns were asked to rate their satisfaction with the lecture on a Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) (Fig. 4 ). Lecture ratings were nearly identical between in-person and virtual formats. Common calls sessions received mean ratings of 4.4 and 4.7 for in-person and virtual delivery, respectively. Drains and tubes sessions received ratings of 4.5 and 4.9, respectively. ICU sessions were rated an average of 4.6 and 4.5, respectively. There were no significant differences in lecture ratings when comparing the two academic years.

FIGURE 4.

Interns Report Similar Usefulness of Lectures with Delivery in Virtual and In Person Formats. Lectures were given similar ratings in the in-person and virtual format of our curriculum with all lectures receiving average mean scores for usefulness on a scale of 1 (useless) to 5 (very useful) of over 4.

Taken together, we concluded that virtual and in-person delivery of an extended intern boot camp curricula results in equal improvements in intern confidence and knowledge acquisition. Additionally, interns are equally satisfied with in-person and virtual curricula, and their preference for these sessions to be led by senior residents is not affected by different curricular delivery methods.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that virtual delivery of intern summer school education sessions is equally as effective compared with in-person delivery of content, contrary to our initial hypothesis. Subjective measures of intern satisfaction and objective measures of intern performance did not show a significant decrease after switching to a virtual mode of teaching. Additionally, interns reported similar satisfaction with lectures and reported no changes in their preferences for senior resident teachers in virtual learning sessions.

After the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the transition to online learning, recent literature has explored the effect of this transition on multiple learning modalities at the medical student and resident level.19 However, much of the research describes innovative and significant shifts in instructional or testing methods,20 not allowing for direct comparison between pre- and post-intervention outcomes. Our summer school format allowed for a unique opportunity to compare similar instructional materials and methods, time points, and evaluation with virtual learning as the only manipulated variable. The findings of our study suggest that virtual learning is equivalent to in-person learning for didactic instructional material that is provided during an intern summer school curriculum. Our study was able to demonstrate Kirkpatrick Level 221 educational outcomes, allowing for demonstration of changes in the knowledge of surgical learners. Changes in intern practice patterns or patient outcomes were not assessed.

There were limitations to our study. We investigated a small number of learners at a single large, academic institution, which may limit the generalizability of the data. As this study was conducted over two different academic years, the individuals in each sample are from different intern classes, and additional differences may exist which may have affected the study. Both classes of interns were comprised of excellent residency candidates with strong academic experience, however no control was made for personal experiences with the material, learning style, or other individualized factors which may have influenced our results. Due to the small sample size, we did not collect demographic data about our participants to prevent participants from feeling as though their quiz scores or curricular evaluations could be identified. This presents a limitation that is common to many multi-year educational research studies with a small number of participants. We are unable to determine if demographic differences between our two samples may have confounded our results. Virtual curricula with larger groups of learners might be able to more adequately address the impact of individual differences on educational outcomes in virtual and in-person formats. Additional iterations of this curriculum which randomly divide interns into virtual or in person learning, or split sessions between in-person and virtual learning would be able to more accurately evaluate these findings.

Interns who participated in the virtual iteration of this curriculum did not have the opportunity to participate in the in-person modality of learning, so no direct comparison by individuals could be made. Additionally, the interns who participated in virtual learning would have had some experience with virtual curricula during the end of their medical school with the shift to remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is unclear if these results would be applicable to participants without previous online learning experience, or if interns would demonstrate the same satisfaction if in-person learning were a possibility.

In most cases, senior resident lecturers were identical between both in person and virtual curricula, however these senior residents had one additional year of clinical training, which may have improved their mastery of the material or teaching style. Finally, these sessions were conducted at the beginning of the academic year and interns were asked to rate their preferences for senior resident or attending teachers. While these junior residents had several weeks of participating in the large-group didactic sessions attended by all surgical residents at our program, we are not certain that this finding would persist once interns had completed additional weeks of residency.

Surgical learning requires both didactic and hands-on components. Didactic learning and evaluation can easily lend itself to the virtual platform, however the use of remote learning for manual skill acquisition and development demonstrates significant challenges. For surgical interns, at the beginning of their training, this is especially important. Many solutions for virtual skills training have been suggested, including at-home use of laparoscopic box trainers, immersive operative room simulation, and use of at-home suturing models.23, 24, 25 At our institution, we utilized several of these innovative strategies to deliver skills-based curricula during our intern summer school. While additional investigation of the effect of this shift is ongoing, due to the significant changes between virtual and hands-on training in the skills aspect of our curriculum, we did not directly compare its effects in this study.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer the unique ability to directly compare the results of an in person and virtual curriculum. While virtual learning easily lends itself to didactic content, it is unlikely that virtual learning will fully replace in-person learning. Surgical interns require procedural instruction which, while remote learning has been demonstrated to be equivalent for basic technical skills,22 cannot replace complex technical learning in an in-person setting. However, virtual learning offers several unique advantages for the surgical intern, including asynchronous participation, which may allow learners to review material at their own pace and/or in a just-in-time fashion. Virtual learning may also allow interns who are working night-shift rotations to review educational material at a separate time without violation of duty hours.

As social distancing requirements are relaxed in the future as the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, surgical educational leaders will need to weigh the potential benefits of virtual learning against its difficulties or pitfalls. With a growing body of data demonstrating the non-inferiority of virtual learning in many educational settings, it is likely that virtual learning in some form will remain a part of many educational endeavors. Additional research is needed to examine the long-term effects of virtual learning and to determine the impact of virtual learning on practice patterns and patient care outcomes.

CONCLUSION

At the completion of a senior resident-led summer school, surgical interns demonstrate gains in surgical knowledge and increased confidence interacting with senior residents. The described curriculum is effective in both in-person and virtual models demonstrating similar knowledge acquisition and improvements in confidence from both modes of educational delivery. As increased virtual education becomes a part of surgical residency, demonstrating the ability of virtual curricula to result in similar or improved outcomes over in-person curricula is an important goal of educational research.

TIES VIRTUAL LEARNING 5.10 - SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS.DOCX

mmc1.docx

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all the members of the Washington University Curriculum Committee who assisted in curricular planning and execution.

Footnotes

Access to the REDCap database is supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Grant [UL1 TR000448] and Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA091842. Dr. Caldwell was provided salary support by the Washington University School of Medicine Surgical Oncology Basic Science and Translational Research Training Program Grant (T32CA009621) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.05.009.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

REFERENCES

- 1.Neylan CJ, Nelson EF, Dumon KR, et al. Medical School Surgical Boot Camps: A Systematic Review. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acosta D, Castillo-Angeles M, Garces-Descovich A, et al. Surgical Practical Skills Learning Curriculum: Implementation and Interns’ Confidence Perceptions. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandian TK, Buckarma EH, Mohan M, et al. At Home Preresidency Preparation for General Surgery Internship: A Pilot Study. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minter RM, Amos KD, Bentz ML, et al. Transition to surgical residency: a multi-institutional study of perceived intern preparedness and the effect of a formal residency preparatory course in the fourth year of medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90:1116–1124. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez GL, Page DW, Coe NP, et al. Boot cAMP: educational outcomes after 4 successive years of preparatory simulation-based training at onset of internship. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryg PA, Hafler JP, Forster SH. The Efficacy of Residents as Teachers in an Ophthalmology Module. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duran-Nelson A, Baum KD, Weber-Main AM, Menk J. Efficacy of peer-assisted learning across residencies for procedural training in dermatology. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:391–394. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00218.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer SJ, Falwell A, Gaba DM, et al. Identifying organizational cultures that promote patient safety. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34:300-311. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181afc10c [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Coe TM, Jogerst KM, Sell NM, et al. Practical Techniques to Adapt Surgical Resident Education to the COVID-19 Era. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e139–e141. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okland TS, Pepper J-P, Valdez TA. How do we teach surgical residents in the COVID-19 era? J Surg Educ. 2020;77:1005–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calhoun KE, Yale LA, Whipple ME, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on medical student surgical education: Implementing extreme pandemic response measures in a widely distributed surgical clerkship experience. Am J Surg. 2020;220(1):44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson KJ, Gronseth SL. Application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Principles to Surgical Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:1008–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabharwal S, Ficke JR, LaPorte DM. How We Do It: Modified Residency Programming and Adoption of Remote Didactic Curriculum During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins GC, Thomson SE, Baker J, et al. COVID-19 lockdown and beyond: Home practice solutions for developing microsurgical skills. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:407–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoopes S, Pham T, Lindo FM, et al. Home Surgical Skill Training Resources for Obstetrics and Gynecology Trainees During a Pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:56–64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shebrain S, Nava K, Munene G, et al. Virtual Surgery Oral Board Examinations in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic. How I Do It! J Surg Educ. 2020;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolu LB, Feyissa GT, Ezeh A, et al. Managing Resident Workforce and Residency Training During COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review of Adaptive Approaches. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:527–535. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S262369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi ART, Klingensmith ME, Malangoni MA, et al. Best Practice for Implementation of the SCORE Portal in General Surgery Residency Training Programs. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:e11–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, et al. Medical and Surgical Education Challenges and Innovations in the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. In Vivo. 2020;34:1603-1611. doi:10.21873/invivo.11950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using Technology to Maintain the Education of Residents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77:729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2006. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Co M, Chung PH-Y, Chu K-M.Online teaching of basic surgical skills to medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case-control study. Surg Today. 25, 2021. http://doi:10.1007/s00595-021-02229-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hoopes S, Pham T, Lindo FM, et al. Home Surgical Skill Training Resources for Obstetrics and Gynecology Trainees During a Pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:56–64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pérez-Escamirosa F, Medina-Alvarez D, Ruíz-Vereo EA, et al. Immersive Virtual Operating Room Simulation for Surgical Resident Education During COVID-19. Surg Innov. 2020;27:549–550. doi: 10.1177/1553350620952183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins GC, Thomson SE, Baker J, et al. COVID-19 lockdown and beyond: Home practice solutions for developing microsurgical skills. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:407–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.