Abstract

Background and Aims

Common mental health symptoms (CMHS) like depressive moods, anxiety, and stress are the underlying causes of suicidal behavior. The incidence of suicide is higher among Bangladeshi students. Due to the pandemic, students of health/rehabilitation sciences are at the most significant risk. This study aimed to measure the prevalence rate and predicting factors for depression, anxiety and stress, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts in Bangladeshi undergraduate rehabilitation students.

Methods

This cross‐sectional study included data from 731 participants. Descriptive analyses estimated prevalence, and multivariate logistic regression models identified the factors associated with CMHS and suicidal behavior after adjusting the confounders.

Results

The result shows a high prevalence of moderate to very severe CMHS and a higher risk of suicidal ideation among rehabilitation students. Sociodemographic factors, illness, behavior, institution, and subject‐related issues were identified as the predicting factors of CMHS and suicidal behavior. The students suffering from mental health symptoms reported suicidal ideation and attempted at a significantly higher rate.

Conclusion

To deal with CHMS and suicide risk, a holistic, supportive approach from government and academic institutions are essential for minimizing the predicting factors identified by this study. The study is helpful for the government regulatory body and policymakers to take immediate steps for preventing CMHS and suicidal behavior among rehabilitation students in Bangladesh.

Keywords: anxiety, Bangladesh, COVID‐19 pandemic, depression, rehabilitation, stress, suicidal behavior, undergraduate student

1. INTRODUCTION

Physiotherapists, Occupational therapists, and Speech and Language therapists are the three significant professionals representing a rehabilitation team. 1 Bangladesh has a few (about 12/million) rehabilitation professionals, and they are poorly regulated, merely recognized, and have yet to be included in mainstream health services. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The country started the undergraduate program in rehabilitation since her independence as a part of the government initiative. The development's initiatives include unification of course curriculum, determining eligibility criteria, and regulating education, employment, and clinical practice through the government regulatory body. 2 , 6 However, most of these initiatives are poorly monitored and filed on official paper only without proper implementation. As a result, large‐scale rehabilitation services are provided and patronized by nongovernment organizations as a charity model. Qualified professionals mainly serve in private chambers, but lack of regulation, physician dominance, and professional conflict with physicians drag them to challenges and lower their credibility. 2 However, the strength of the rehabilitation professionals arises from the extensive service demand: 10%–15% of the population are persons with disabilities, 7 increment of the elderly population, 8 and survivors of non‐communicable disease. 9

Students of rehabilitation have the dream of serving as a health professional inspired by this colossal service demand. The undergraduate programs are affiliated with the university, and the professional scope of health service contribution for the imposed social demand motivates them to enter a rehabilitation degree program. Gradually, they observe poor staffing, a lower standard of the educational environment, and poor regulation. 6 These professional issues and comparative inequality with other health professionals are driving factors for depressive symptoms. There is a higher chance of developing mental health symptoms or even suicidal behavior among rehabilitation students. The reason might not be solely professional issues, but mental health issues are a growing concern among university students in Bangladesh. These common mental health symptoms (CMHS) can be evident through depression, anxiety, and stress.

In Bangladesh, depression, anxiety, and stress prevalence are as high as 54.3%, 64.8%, and 59.0%, respectively. 10 Previous studies suggested that other factors, academic environment, and subject‐related future worries are strongly associated with mental health problems in Bangladeshi undergraduate universities. 10 , 11 Additionally, the COVID‐19 pandemic poses an enormous threat to the mental health of the world population. This unprecedented situation has victimized students by putting them at a higher risk of mental health problems. 12 A study conducted among Bangladeshi university students suggested that at the time of the COVID‐19 pandemic rise, 62.9%, 63.6%, and 58.6% of university students showed depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, respectively. 13

CMHS is found to be the underlying factor for most suicide cases. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 The incidence of suicide is even higher among the student cohort in Bangladesh. 18 , 19 Specifically, health science students are at the most significant risk, 20 and this pandemic fueled the fire. Our previous study among Bangladeshi rehabilitation professionals and Pakistani rehabilitation students revealed a remarkably high prevalence of CMHS. 6 , 21 Given this high prevalence among these cohorts suggested additional study among Bangladeshi rehabilitation students. Therefore, the current study aimed to (1) measure the prevalence rate of depression, anxiety and stress, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt; (2) identify the factors predicting depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt among undergraduate rehabilitation students in Bangladesh.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants and data collection

This cross‐sectional study was conducted between January 7 and March 27, 2021. We have collected data from the students studying Bachelor of Science in Physiotherapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech and Language Therapy. Students from all the institutes of Bangladesh had participated in this study. A margin of 2.5% error, a confidence level of 95%, and a response distribution of 50% were used to calculate the sample size to target a population of 1200 students and secure a minimum sample size of 675 participants. This sample size calculation technique was found suitable in a previous Bangladeshi study. 22 However, 800 undergraduate rehabilitation students were invited by email provided by respective institutes. By giving a 94.1% response rate, 753 students have filled and submitted the provided questionnaire prepared by the “Google Form” platform. However, we have considered data from 731 participants who answered all the questions consistently for the final analysis.

2.2. Sociodemographic, behavior, health, and study subject‐related factors

A wide range of sociodemographic, behavioral, and health‐related factors, study subject, institute, and future career‐related factors were included in the self‐reported questionnaire.

The sociodemographic factors asked in the questionnaire comprised of age, gender, relationship status, family type, resident type, monthly family income, regular religious practice (yes/no), regular exercise habit (yes/no), smoking habit (yes/no), average hours of sleep per night, the satisfaction of sleep quality (yes/no), and hours of daily social media use. In this section, participants were asked if they had suffered from physical and mental conditions in the past year, if they had had a hard time last year and if they had COVID‐19. Participants were also asked if they take any antipsychotic drug or sleeping pill. All these questions have a dichotomous answer (yes/no).

Study subject, institute, and future career‐related factors include study year (first to final year), satisfaction regarding the academic environment, and academic result. Participants were asked questions about subject suitability and their future, for example, (a) do you think rehabilitation is suitable for you, (b) did you know about rehabilitation before you were admitted here, (c) do you think the future of rehabilitation science (RS) bright, (d) will you change this subject if get an opportunity, (e) do you suffer from identity crisis or inferiority complex as a rehabilitation student, (f) do you think admitting here was a right decision? Furthermore, participants were also asked about a future career question and the persons who influenced them to admit to RS (specify what RS is). Finally, participants were asked two more general questions: (a) Do you think the mental health problems you are suffering are COVID‐19 related, (b) Do you think that the mental health problems you are suffering are subject related.

2.3. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS‐21)

This study used the Bangla version Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale‐21 (DASS‐21) 10 , 13 , 23 to assess depression, anxiety, and stress. Predefined thresholds for mild, moderate to severe, or extremely severe symptom levels were used to categorize depression, anxiety, and stress levels. For depression symptoms, cutoff points were as follows: normal 0–9, mild 10–13, moderate 14–20, severe 21–27, and extremely severe +28. For anxiety, 0–7, 8–9, 10–14, 15–19, and +20 points were considered as normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe symptoms, respectively. Stress symptoms were categorized as normal (0–14), mild (15–18), moderate (19–25), severe (26–33), and extremely severe +34. 6 , 13

2.4. Suicidal behavior

To measure suicidal behavior, a suicidal behavior questionnaire contained two items that were included: (1) suicidal ideation (have you seriously considered suicide in the last 12 months?), and (2) attempted suicide (have you attempted suicide in last year?). 11 , 24 , 25 The response options were yes and no.

2.5. Data analysis

SPSS version 22.0 software was applied for data analysis. For descriptive analysis, moderate, severe, and very severe were combined to calculate depression, anxiety, and stress scores on the DASS‐21. 6 , 26 , 27 Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, percentages, and χ 2/Fisher's exact tests) were used for categorical data. After adjusting the confounders, multivariable logistic regression models were employed to identify the factors associated with mental health symptoms. The results were interpreted with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values. We consider a p‐value less than or equal to 0.05 as significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Prevalence of mental health symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt

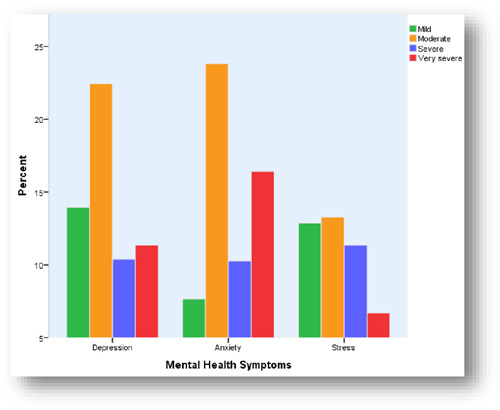

The prevalence of moderate to very severe depression, anxiety and stress were 44.2%, 50.5%, and 31.3%. However, 14% mild, 22% moderate, 10% severe, and 11% very severe depression; 8% mild, 24% moderate, 10% severe, and 16% very severe anxiety; 13% mild and moderate, 11% severe, and 7% very severe stress symptoms were recorded in this study. On the other hand, 16.3% of participants had suicidal ideation in the last year, and 3% attempted suicide. Details can be found in Tables 1, 2, and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis

| Variables | N (%) | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | Suicidal ideation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | p value | Yes, n (%) | p value | Yes, n (%) | p value | Yes, n (%) | p value | ||

| Total | 731 (100) | 323 (44.2) | – | 369 (50.5) | – | 229 (31.3) | – | 119 (16.3) | – |

| Subject | 0.269 | 0.519 | 0.474 | 0.675 | |||||

| Physiotherapy | 561 (76.85) | 256 (45.6) | 288 (51.3) | 181 (32.3) | 93 (16.6) | ||||

| Occupational therapy | 60 (8.21) | 26 (43.3) | 31 (51.7) | 19 (31.7) | 11 (18.3) | ||||

| Speech therapy | 110 (15.04) | 41 (37.3) | 50 (45.5) | 29 (26.4) | 15 (13.6) | ||||

| Gender | 0.050 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.025 | |||||

| Female | 355 (48.56) | 170 (47.9) | 197 (55.5) | 133 (37.5) | 69 (19.4) | ||||

| Male | 376 (51.44) | 153 (40.7) | 172 (45.7) | 96 (25.5) | 50 (13.3) | ||||

| Age group | 0.964 | 0.342 | 0.825 | 0.247 | |||||

| ≤20 | 148 (20.25) | 66 (44.6) | 80 (54.1) | 48 (32.4) | 22 (14.9) | ||||

| 21–24 | 499 (68.26) | 221 (44.3) | 252 (50.5) | 157 (31.5) | 88 (17.6) | ||||

| ≥25 | 84 (11.5) | 36 (42.9) | 37 (44) | 24 (28.6) | 9 (10.7) | ||||

| Relationship status | 0.899 | 0.118 | 0.100 | 0.470 | |||||

| Single | 560 (76.6) | 245 (43.8) | 276 (49) | 166 (29.6) | 86 (15.4) | ||||

| In a relationship | 102 (13.95) | 46 (45.1) | 50 (49) | 34 (33.3) | 20 (19.6) | ||||

| Married | 69 (9.4) | 32 (46.4) | 43 (62.3) | 29 (42) | 13 (18.8) | ||||

| Family type | 0.533 | 0.125 | 0.296 | 0.208 | |||||

| Nuclear | 590 (80.7) | 190 (32.2) | 306 (51.9) | 190 (32.2) | 101 (17.1) | ||||

| Joint | 141 (19.3) | 39 (27.7) | 63 (44.7) | 39 (27.7) | 18 (12.8) | ||||

| Resident type | 0.143 | 0.027 | 0.006 | 0.149 | |||||

| Rented | 213 (29.14) | 106 (49.8) | 124 (58.2) | 85 (39.9) | 39 (18.3) | ||||

| Own | 292 (39.95) | 124 (42.5) | 137 (46.9) | 81 (27.7) | 38 (13) | ||||

| Hostel/mess | 226 (30.92) | 93 (41.2) | 108 (47.8) | 63 (27.9) | 42 (18.6) | ||||

| Family income (BDT) | 0.331 | 0.050 | 0.362 | 0.005 | |||||

| ≤15,000 | 167 (22.85) | 81 (48.5) | 97 (58.1) | 58 (34.7) | 40 (24) | ||||

| 15,000–30,000 | 330 (45.14) | 146 (44.2) | 165 (50.0) | 95 (28.8) | 51 (15.5) | ||||

| ≥30,000 | 234 (32.01) | 96 (41.0) | 107 (45.7) | 76 (32.5) | 28 (12.0) | ||||

| Permanent address | 0.701 | 0.996 | 0.786 | 0.311 | |||||

| Village | 336 (45.96) | 143 (42.6) | 169 (50.3) | 104 (31.0) | 48 (14.3) | ||||

| Town | 237 (32.42) | 109 (46.0) | 120 (50.6) | 78 (32.9) | 40 (16.9) | ||||

| Semi‐town | 158 (21.61) | 71 (44.9) | 80 (50.6) | 47 (29.7) | 31 (19.6) | ||||

| Perform 30 min physical exercise | 0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.026 | |||||

| No | 502 (68.67) | 243 (48.4) | 270 (53.8) | 183 (36.5) | 92 (18.3) | ||||

| Yes | 229 (31.33) | 80 (34.9) | 99 (43.2) | 46 (20.1) | 27 (11.8) | ||||

| Regular religious practice | 0.023 | 0.111 | 0.001 | 0.022 | |||||

| No | 224 (30.64) | 113 (50.4) | 123 (54.9) | 90 (40.2) | 47 (21.0) | ||||

| Yes | 507 (69.36) | 210 (41.4) | 246 48.5) | 139 (27.4) | 72 (14.2) | ||||

| Smoking habit | 0.684 | 0.354 | 0.461 | 0.193 | |||||

| No | 678 (92.75) | 301 (44.4) | 339 (50.0) | 210 (31.0) | 107 (15.8) | ||||

| Yes | 53 (7.25) | 22 (41.5) | 30 (56.6) | 19 (35.8) | 12 (22.6) | ||||

| Got physical illness last year | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.013 | |||||

| No | 365 (49.9) | 142 (38.9) | 143 (39.2) | 83 (22.7) | 47 (12.9) | ||||

| Yes | 366 (50.1) | 181 (49.5) | 226 (61.7) | 146 (39.9) | 72 (19.7) | ||||

| Got mental illness last year | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 434 (59.4) | 139 (32) | 165 (38) | 85 (19.6) | 33 (7.6) | ||||

| Yes | 297 (40.6) | 184 (62) | 204 (68.7) | 144 (48.5) | 86 (29) | ||||

| Passed hard time last year | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 220 (30.1) | 47 (21.4) | 66 (30) | 29 (13.2) | 6 (2.7) | ||||

| Yes | 511 (69.9) | 276 (54) | 303 (59.3) | 200 (39.1) | 113 (22.1) | ||||

| Use sleeping pill | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 680 (93.02) | 287 (42.2) | 327 (48.1) | 199 (29.3) | 100 (14.7) | ||||

| Yes | 51 (6.98) | 36 (70.6) | 42 (82.4) | 30 (58.8) | 19 (37.3) | ||||

| Satisfied with sleeping quality | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 216 (29.55) | 144 (66.7) | 151 (69.9) | 115 (53.2) | 58 (26.9) | ||||

| Yes | 515 (70.45) | 179 (34.8) | 218 (42.3) | 114 (22.1) | 61 (11.8) | ||||

| Night time sleeping hour | 0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Normal 7–9 | 449 (61.42) | 181 (40.3) | 213 (47.4) | 112 (24.9) | 53 (11.8) | ||||

| More than normal >9 | 38 (5.2) | 12 (31.6) | 14 (36.8) | 10 (26.3) | 7 (18.4) | ||||

| Less than normal <7 | 244 (33.38) | 130 (53.3) | 142 (58.2) | 107 (43.9) | 59 (24.2) | ||||

| Onscreen time | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | |||||

| <2 | 92 (12.6) | 28 (30.4) | 37 (40.2) | 22 (23.9) | 19 (20.7) | ||||

| 2–4 | 310 (42.4) | 127 (41) | 142 (45.8) | 82 (26.5) | 31 (10.0) | ||||

| 5–6 | 196 (26.8) | 87 (44.4) | 110 (56.1) | 70 (35.7) | 37 (18.9) | ||||

| >6 | 133 (18.2) | 81 (60.9) | 80 (60.2) | 55 (41.4) | 32 (24.1) | ||||

| Got COVID‐19 | 0.527 | 0.177 | 0.604 | 0.394 | |||||

| No | 688 (94.12) | 302 (43.9) | 343 (49.9) | 214 (31.1) | 110 (16.0) | ||||

| Yes | 43 (5.88) | 21 (48.8) | 26 (60.5) | 15 (34.9) | 9 (20.9) | ||||

| Study year | 0.432 | 0.134 | 0.610 | 0.036 | |||||

| First | 310 (42.41) | 135 (43.5) | 160 (51.6) | 102 (32.9) | 60 (19.4) | ||||

| Second | 162 (22.16) | 67 (41.4) | 80 (49.4) | 45 (27.8) | 28 (17.3) | ||||

| Third | 141 (19.29) | 61 (43.3) | 61 (43.3) | 42 (29.8) | 12 (8.5) | ||||

| Forth/final | 118 (16.14) | 60 (50.8) | 68 (57.6) | 40 (33.9) | 19 (16.1) | ||||

| Satisfy with academic environment | <0.001 | 0.120 | <0.001 | 0.261 | |||||

| No | 238 (32.56) | 131 (55) | 130 (54.6) | 98 (41.2) | 44 (18.5) | ||||

| Yes | 493 (67.44) | 192 (38.9) | 239 (48.5) | 131 (26.6) | 75 (15.2) | ||||

| Academic result | 0.001 | 0.320 | 0.004 | 0.050 | |||||

| Excellent | 50 (6.84) | 19 (38) | 29 (58) | 15 (30) | 6 (12) | ||||

| Good | 300 (41.04) | 113 (37.7) | 140 (46.7) | 75 (25) | 37 (12.3) | ||||

| Fair | 131 (17.92) | 72 (55) | 70 (53.4) | 51 (38.9) | 24 (18.3) | ||||

| Poor | 33 (4.51) | 22 (66.7) | 20 (60.6) | 17 (51.5) | 9 (27.3) | ||||

| Not applicable | 217 (29.69) | 97 (44.7) | 110 (50.7) | 71 (32.7) | 43 (19.8) | ||||

| Do you think rehabilitation is a suitable subject for you | 0.028 | 0.481 | 0.097 | 0.006 | |||||

| No | 87 (11.9) | 48 (55.2) | 47 (54) | 34 (39.1) | 23 (26.4) | ||||

| Yes | 644 (88.1) | 275 (42.7) | 322 (50) | 195 (30.3) | 96 (14.9) | ||||

| Know about your subject before admission | 0.036 | 0.132 | 0.982 | 0.808 | |||||

| No | 472 (64.6) | 222 (47) | 248 (52.5) | 148 (31.4) | 78 (16.5) | ||||

| Yes | 259 (35.4) | 101 (39) | 121 (46.7) | 81 (31.3) | 41 (15.8) | ||||

| Future of your subject bright | 0.007 | 0.058 | 0.001 | 0.087 | |||||

| No | 165 (22.57) | 88 (53.3) | 94 (57) | 69 (41.8) | 34 (20.6) | ||||

| Yes | 566 (77.43) | 235 (41.5) | 275 (48.6) | 160 (28.3) | 85 (15) | ||||

| Intension of changing your subject | 0.002 | 0.270 | 229 (31.4) | 0.042 | 119 (16.3) | 0.014 | |||

| No | 588 (80.4) | 243 (41.4) | 290 (49.4) | 174 (29.6) | 86 (14.7) | ||||

| Yes | 143 (19.6) | 80 (55.9) | 78 (54.5) | 55 (38.5) | 33 (23.1) | ||||

| Identity crisis as rehabilitation student | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 350 (47.88) | 125 (35.7) | 156 (44.6) | 80 (22.9) | 40 (11.4) | ||||

| Yes | 381 (52.12) | 198 (52) | 213 (55.9) | 149 (39.1) | 79 (20.7) | ||||

| Inferior complexity as rehabilitation student | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 552 (75.51) | 206 (37.3) | 258 (46.7) | 141 (25.5) | 74 (13.4) | ||||

| Yes | 179 (24.49) | 117 (65.4) | 111 (62) | 88 (49.2) | 45 (25.1) | ||||

| Get a suitable job after completing course | 0.001 | 0.153 | 0.005 | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 149 (20.38) | 84 (56.4) | 83 (55.7) | 61 (40.9) | 38 (25.5) | ||||

| Yes | 582 (79.62) | 239 (41.1) | 286 (49.1) | 168 (28.9) | 81 (13.9) | ||||

| Do you think it was right decision to choice rehabilitation | <0.001 | 0.045 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 117 (16) | 70 (59.8) | 69 (59) | 55 (47) | 32 (27.4) | ||||

| Yes | 614 (84) | 253 (41.2) | 300 (48.9) | 174 (28.3) | 87 (14.2) | ||||

| Will you change profession after graduation | 0.001 | 0.368 | 0.006 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 615 (84.13) | 255 (41.5) | 306 (49.8) | 180 (29.3) | 84 (13.7) | ||||

| Yes | 116 (15.87) | 68 (58.6) | 63 (54.3) | 49 (42.2) | 35 (30.2) | ||||

| Were you bound to admit here | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.366 | |||||

| No | 558 (76.33) | 226 (40.5) | 264 (47.3) | 163 (29.2) | 87 (15.6) | ||||

| Yes | 173 (23.67) | 97 (56.1) | 105 (60.7) | 66 (38.2) | 32 (18.5) | ||||

| COVID pandemic causing mental health symptoms | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.905 | 0.984 | |||||

| No | 497 (68) | 192 (38.6) | 235 (47.3) | 155 (31.2) | 81 (16.3) | ||||

| Yes | 234 (32) | 131 (56) | 134 (57.3) | 74 (31.6) | 38 (16.2) | ||||

| Subject causing mental symptoms | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 597 (81.67) | 225 (37.7) | 280 (46.9) | 157 (26.3) | 84 (14.1) | ||||

| Yes | 134 (18.33) | 98 (73.1) | 89 (66.4) | 72 (53.7) | 35 (26.1) | ||||

Note: Sociodemographic, illness, behavior, institution, subject‐related factors and depression, anxiety, stress symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis

| Variables | Suicidal ideation | p value | Suicide attempt | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| All | 119 (16.3) | 612 (83.7) | – | 22 (3.0) | 709 (97.0) | – |

| Depression symptoms | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 24 (5.9) | 384 (94.1) | 3 (0.70) | 405 (99.3) | ||

| Yes | 95 (29.4) | 228 (70.6) | 19 (5.9) | 304 (94.1%) | ||

| Anxiety symptoms | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 25 (6.9) | 337 (93.1) | 4 (1.10) | 358 (98.9%) | ||

| Yes | 94 (25.5) | 275 (74.5) | 18 (4.90) | 351 (95.1) | ||

| Stress symptoms | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 38 (7.6) | 464 (92.4) | 5 (1.0) | 497 (99.0) | ||

| Yes | 81 (35.4) | 148 (64.6) | 17 (7.40) | 709 (92.6) | ||

Note: Mental health symptoms with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Figure 1.

Percent of participants experiencing mental health symptoms, stratified by severity using DASS‐21 (depression, anxiety and stress) (N = 731)

3.2. Sociodemographic, behavior, and health‐related factors, and mental health symptoms and suicidal ideation

Around half (48.56%) of the participants were female; the mean age was 22.20 (SD = 2.33). Significantly higher prevalence has been found among female participants for depression (p = 0.050), anxiety (p = 0.008), stress (p = 0.001) and suicidal ideation (p = 0.025). In this study, 76% of students were single, 80% have come from a nuclear family, 39% lived in their own house, 45% were from a middle‐class family (monthly family income 15,000–30,000 [currency?]), 46% were from rural villages. However, those who lived in a rented house reported anxiety (p = 0.027) and stress (p = 0.006) at a higher rate. Similarly, participants from middle‐income family showed higher stress symptoms (p = 0.050) and suicidal ideation (p = 0.005).

A total of 68% of participants said they do not perform regular exercise, 69% practice religion, and only 7% smoke regularly. Statistically, a significantly higher rate of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation has been found in those who do not perform the exercise and religious practice regularly, p = 0.001/0.023, p = 0.008/0.111, p < 0.001/0.001, and p = 0.026/0.022, respectively for depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation.

In this study, 50% of participants said that they had suffered from physical illness last year, while 40% and 70% had faced mental health conditions and hard times, respectively. Though 30% of the participants were not satisfied with their sleep quality, only less than 7% use sleeping pill or similar drugs. Only 33% of participants said they used to sleep <7 h at night, and 18.2% spent >6 h on screen. However, all the participants mentioned above showed a statistically significant higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal ideation. Details can be found in Table 1.

3.3. Study subject, institute and future career‐related factors, mental health symptoms, and suicidal ideation

In this study, 42% of students were in the first year (old and new first year), and a statistically significant number thought about committing suicide in the last year (p = 0.036). On the other hand, one‐third of the participants were not satisfied with the academic environment of their respective institutes, and a high number of them were suffering from depression and stress symptoms (p ≤ 0.001). A total of 77% of the participants were optimistic about the future of their study subjects, and less number of them reported depression and stress (p = 0.007 and p = 0.001). About 20% of students want to change their study subject if a chance is given, and most of them reported depression, stress, and suicidal ideation (p = 0.002, p = 0.042, p = 0.014).

Additionally, the participants were questioned whether they are suffering from identity crisis and inferiority complex as RS students. Surprisingly, 52% and 24% answered yes, respectively. A 16% of participants said that admitting to this subject was not correct. Unsurprisingly, a significantly high number of these subgroup participants reported all mental health symptoms with suicidal ideation. Table 1 depicts the statistics in detail.

Finally, one‐third of the participants thought that the mental health problems they were suffering from were due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, while one‐fourth thought these were due to the subject they were studying. However, those who thought the mental health problems they are suffering from due to their subject have reported in significantly high rate for all the given mental health problems (p ≤ 0.001) and suicidal ideation (p = 0.001). Detailed results can be found in Table 1.

3.4. Multivariable analysis

Multivariable logistic regression suggested that being female, living in a rented house, not performing physical exercise, physical illness, facing mental health conditions, and challenging times, using the sleeping pill or similar drugs, sleeping less than regular hours, dissatisfaction with sleeping quality, high onscreen time (>6 h), inferiority complex, poor academic performance and changing profession after graduation were statistically significantly associated with mental health symptoms and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, from the logistic regression, it has been revealed that subject‐related mental health was the common factor for all given mental health symptoms and suicidal ideation. Details have been given in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of the variables with depression

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.492 | 1.032–2.158 | 0.033 |

| Male | Reference | ||

| Perform 30 min physical exercise | |||

| No | 1.450 | 0.973–2.162 | 0.068 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Regular religious practice | |||

| No | 1.087 | 0.732–1.615 | 0.679 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Got physical illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.912 | 0.634–1.311 | 0.618 |

| Got mental illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.604 | 1.089–2.362 | 0.017 |

| Passed hard time last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.623 | 1.693–4.063 | <0.001 |

| Use sleeping pill | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.406 | 1.148–5.042 | 0.020 |

| Night time sleeping hour | |||

| Normal (7–9 h) | 1.461 | 0.942–2.265 | 0.090 |

| More than 9 h | 0.385 | 0.157–0.944 | 0.037 |

| Less than 7 h | Reference | ||

| Satisfied with sleep quality | |||

| No | 2.677 | 1.687–4.249 | <0.001 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Onscreen time | |||

| <2 h | Reference | ||

| 2–4 h | 1.238 | 0.688–2.230 | 0.476 |

| 5–6 h | 1.571 | 0.850–0.850 | 0.149 |

| >6 h | 2.397 | 1.214–4.730 | 0.012 |

| Satisfy with academic environment | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.771 | 0.512–1.161 | 0.213 |

| Academic result | |||

| Excellent | Reference | ||

| Good | 0.597 | 0.287–1.240 | 0.167 |

| Fair | 1.203 | 0.541–2.677 | 0.651 |

| Poor | 1.549 | 0.503–4.769 | 0.446 |

| Not applicable | 0.825 | 0.393–1.731 | 0.612 |

| Study subject suitability | |||

| No | 2.092 | 1.018–4.303 | 0.045 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Know about your subject before admission | |||

| No | 0.978 | 0.666–1.437 | 0.911 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Future of your subject bright | |||

| No | 1.443 | 0.858–2.427 | 0.167 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Intension of changing your subject | |||

| No | 1.051 | 0.586–1.886 | 0.867 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Identity crisis as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.973 | 0.652–1.451 | 0.894 |

| Inferior complexity as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.668 | 0.982–2.832 | 0.050 |

| Get a suitable job after completing course | |||

| No | 0.826 | 0.477–1.431 | 0.496 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Were you bound to admit here | |||

| No | 0.777 | 0.497–1.214 | 0.267 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Do you think it was right decision to choice rehabilitation | |||

| No | 0.993 | 0.519–1.900 | 0.984 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Will you change profession after graduation | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.302 | 0.704–2.405 | 0.400 |

| COVID pandemic causing mental health symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.599 | 1.086–2.356 | 0.017 |

| Subject causing mental symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.598 | 2.010–6.441 | <0.001 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of the variables with anxiety

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.525 | 1.078–2.158 | 0.017 |

| Male | Reference | ||

| Resident type | |||

| Rented | 1.420 | 0.908–2.220 | 0.124 |

| Own | 1.126 | 0.741–1.712 | 0.578 |

| Hostel/mess | Reference | ||

| Family income (BDT) | |||

| ≤15,000 | 1.984 | 1.232–3.195 | 0.005 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 1.254 | 0.851–1.847 | 0.253 |

| ≥30,000 | Reference | ||

| Perform 30 min physical exercise | |||

| No | 1.214 | 0.834–1.767 | 0.312 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Got physical illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.745 | 1.240–2.454 | 0.001 |

| Got mental illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.137 | 1.471–3.105 | <0.001 |

| Passed hard time last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.682 | 1.124–2.516 | 0.011 |

| Use sleeping pill | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.165 | 1.400–7.156 | 0.006 |

| Night time sleeping hour | |||

| Normal (7–9 h) | Reference | ||

| More than 9 h | 0.265 | 0.116–0.603 | 0.002 |

| Less than 7 h | 0.732 | 0.485–1.106 | 0.138 |

| Satisfied with sleep quality | |||

| No | 2.290 | 1.484–3.536 | <0.001 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Onscreen time | |||

| <2 h | Reference | ||

| 2–4 h | 1.163 | 0.673–2.007 | 0.588 |

| 5–6 h | 1.670 | 0.936–2.980 | 0.083 |

| >6 h | 1.736 | 0.916–3.291 | 0.091 |

| Future of your subject bright | |||

| No | 0.887 | 0.560–1.405 | 0.609 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Identity crisis as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.010 | 0.688–1.482 | 0.961 |

| Inferior complexity as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.063 | 0.647–1.746 | 0.811 |

| Were you bound to admit here | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.368 | 0.910–2.057 | 0.132 |

| Do you think it was right decision to choice rehabilitation | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.271 | 0.726–2.224 | 0.401 |

| COVID pandemic causing mental health symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.084 | 0.750–1.567 | 0.668 |

| Subject causing mental symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.714 | 0.999–2.941 | 0.050 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of the variables with stress

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.808 | 1.215–2.688 | 0.003 |

| Male | Reference | ||

| Resident type | |||

| Rented | 1.852 | 1.131–3.031 | 0.014 |

| Own | 1.330 | 0.823–2.148 | 0.244 |

| Hostel/mess | Reference | ||

| Perform 30 min physical exercise | |||

| No | 1.872 | 1.199–2.923 | 0.006 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Regular religious practice | |||

| No | 1.423 | 0.948–2.137 | 0.089 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Got physical illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.388 | 0.946–2.036 | 0.093 |

| Got mental illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.100 | 1.409–3.130 | <0.001 |

| Passed hard time last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.949 | 1.177–3.225 | 0.009 |

| Use sleeping pill | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.044 | 1.026–4.071 | 0.042 |

| Night time sleeping hour | |||

| Normal (7–9 h) | Reference | ||

| More than 9 h | 0.495 | 0.202–1.212 | 0.124 |

| Less than 7 h | 1.230 | 0.794–1.905 | 0.354 |

| Satisfied with sleep quality | |||

| No | 2.115 | 1.353–3.305 | 0.001 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Onscreen time | |||

| <2 h | Reference | ||

| 2–4 h | 0.905 | 0.478–1.715 | 0.760 |

| 5–6 h | 1.345 | 0.696–2.598 | 0.377 |

| >6 h | 1.190 | 0.580–2.441 | 0.634 |

| Satisfy with academic environment | |||

| No | 1.235 | 0.808–1.887 | 0.330 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Academic result | |||

| Excellent | Reference | ||

| Good | 0.415 | 0.183–0.937 | 0.034 |

| Fair | 0.690 | 0.289–1.648 | 0.404 |

| Poor | 1.121 | 0.366–3.434 | 0.841 |

| Not applicable | 0.665 | 0.294–1.503 | 0.327 |

| Future of your subject bright | |||

| No | 0.968 | 0.576–1.625 | 0.901 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Intension of changing your subject | |||

| No | 1.530 | 0.836–2.801 | 0.168 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Identity crisis as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.264 | 0.822–1.944 | 0.285 |

| Inferior complexity as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.471 | 0.862–2.511 | 0.157 |

| Get a suitable job after completing course | |||

| No | 0.775 | 0.445–1.348 | 0.366 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Were you bound to admit here | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.903 | 0.574–1.421 | 0.659 |

| Do you think it was right decision to choice rehabilitation | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.001 | 0.540–1.857 | 0.996 |

| Will you change profession after graduation | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.883 | 0.493–1.581 | 0.675 |

| Subject causing mental symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.212 | 1.272–3.847 | 0.005 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of the variables with suicidal ideation

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.736 | 1.069–2.822 | 0.026 |

| Male | Reference | ||

| Family income (BDT) | |||

| ≤15,000 | 2.843 | 1.491–5.422 | 0.002 |

| 15,000–30,000 | 1.429 | 0.803–2.541 | 0.225 |

| ≥30,000 | Reference | ||

| Perform 30 min physical exercise | |||

| No | 1.617 | 0.926–2.824 | 0.091 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Regular religious practice | |||

| No | 1.222 | 0.740–2.017 | 0.433 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Got physical illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.829 | 0.515–1.333 | 0.439 |

| Got mental illness last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.987 | 1.782–5.006 | <0.001 |

| Passed hard time last year | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.970 | 2.016–12.252 | <0.001 |

| Use sleeping pill | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.528 | 1.156–5.528 | 0.020 |

| Night time sleeping hour | |||

| Normal (7–9 h) | Reference | ||

| More than 9 h | 0.806 | 0.284–2.285 | 0.685 |

| Less than 7 h | 1.590 | 0.921–2.745 | 0.096 |

| Satisfied with sleep quality | |||

| No | 1.031 | 0.594–1.790 | 0.913 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Onscreen time | |||

| <2 h | 0.243 | 0.114–0.520 | <0.001 |

| 2–4 h | 0.640 | 0.308–1.326 | 0.230 |

| 5–6 h | 0.697 | 0.314–1.547 | 0.374 |

| >6 h | Reference | ||

| Study year | |||

| First year | 1.694 | 0.748–3.837 | 0.206 |

| Second year | 1.661 | 0.780–3.535 | 0.188 |

| Third year | 0.565 | 0.234–1.365 | 0.204 |

| Final year | Reference | ||

| Academic result | |||

| Excellent | Reference | ||

| Good | 0.934 | 0.303–2.882 | 0.906 |

| Fair | 1.858 | 0.558–6.184 | 0.313 |

| Poor | 1.897 | 0.453–7.953 | 0.381 |

| Not applicable | 1.191 | 0.353–4.024 | 0.778 |

| Do you think rehabilitation is a suitable subject for you | |||

| No | 1.208 | 0.544–2.684 | 0.643 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Intension of changing your subject | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.790 | 0.376–1.662 | 0.535 |

| Identity crisis as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.591 | 0.924–2.738 | 0.094 |

| Inferior complexity as rehabilitation student | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.841 | 0.437–1.619 | 0.604 |

| Get a suitable job after completing course | |||

| No | 1.449 | 0.772–2.721 | 0.248 |

| Yes | Reference | ||

| Were you bound to admit here | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.903 | 0.574–1.421 | 0.659 |

| Do you think it was right decision to choice RS | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.778 | 0.365–1.658 | 0.515 |

| Will you change profession after graduation | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.207 | 1.102–4.420 | 0.026 |

| Subject causing mental symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.796 | 0.415–1.525 | 0.491 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

3.5. Association between mental health symptoms and suicidal behavior

It was revealed that a higher portion of participants who were suffering from mental health symptoms reported suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. The regression analysis suggested that depression and stress symptoms were the statistically significant predictors of suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] = 2.96, 95% CI = 1.7–5.2, p ≤ 0.001; OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.7–5.0, p ≤ 0.001). On the other hand, stress was significantly associated with suicide attempts (OR = 3.64, 95% CI = 1.1–12.5, p = .040; Tables 7 and 8).

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of the mental health symptoms with suicidal ideation

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.959 | 1.673–5.233 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.665 | 0.951–2.917 | 0.075 |

| Stress symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.966 | 1.752–5.020 | <0.001 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

Table 8.

Logistic regression analysis of the mental health symptoms with suicide attempt

| Variables | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.469 | 0.821–14.655 | 0.091 |

| Anxiety symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.329 | 0.371–4.757 | 0.662 |

| Stress symptoms | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.643 | 1.063–12.486 | 0.040 |

Note: Bold faces are significant at 5% significance level.

4. DISCUSSION

This study found a high prevalence of moderate to very severe CMHS and a higher risk of suicidal ideation among Bangladeshi rehabilitation science students. These higher levels of prevalence and risk were clustered by gender, resident type, family income, physical exercise, institute related‐factors, and psychological health‐related factors. The students suffering from mental health symptoms reported suicidal ideation and attempted at a significantly higher rate. The study is helpful for the government regulatory body, and policymakers take an immediate step for preventing CMHS and suicidal issues.

A recent systematic review and meta‐analyses suggested that the global prevalence rate of depression and anxiety among health science students was 28% and 34%, respectively. 28 , 29 Another systematic review suggested that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in South Asia during this pandemic was 34% and 41%, respectively. 30 In contrast, we found that about 50% of the participants were suffering from moderate to very severe types of depression and anxiety symptoms, which is much higher than the global and pandemic time rate in South Asia. Similar to our study, another evaluation conducted during the pandemic among Bangladeshi medical college students also suggested that 50% and 65% of the participants were suffering from at least a mild type of depression and anxiety, respectively. 31 Furthermore, an additional study conducted during the pandemic among Indian medical students revealed that around one‐third were suffering from mild to very severe types of anxiety and stress, while 50% reported mild to very severe depression. 32 Another study conducted during the pandemic in the United States among medical college students reported a lower rate of depression (24%) and anxiety (30%) prevalence. 33 Prepandemic Bangladeshi data‐based systematic review estimated up to 31% prevalence of CMHS among the general population. 34 Our previous study with Bangladeshi rehabilitation professionals (not students) found the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress 51.0%, 58.6%, and 33.6%, respectively. 6 CMHS was associated with economic stressors, professional and employment‐related factors in that study. 6

A 2016 systematic review and meta‐analysis suggested that the overall global prevalence of suicidal ideation among medical students was 11.1% (95% CI: 9.0%–13.7%). 35 Another recent systematic review revealed that the annual prevalence of suicidal ideation amongst adolescent students was 14.0% (95% CI: 10.0%–17.0%). A prepandemic Bangladeshi study suggested that the annual prevalence of suicidal ideation in university students was 14.7%. 36 However, recent reports suggested that the prevalence of suicidal behavior has been significantly increased globally since last year due to the pandemic. 37 , 38 Nonetheless, a study conducted in the pandemic among undergraduate Bangladeshi university students found that the annual prevalence of suicidal ideation was 12.8%. 39 A similar study among healthcare workers and the general population found the prevalence of suicidal behavior at 6.1%. 40 In contrast, we found a significantly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation (16.3%) and suicidal attempts (3.0%) among rehabilitation students in Bangladesh. Our study also revealed that above half of the participants suffer from an identity crisis as rehabilitation students. However, one‐third of the participants were not satisfied with the academic environment, and one‐fourth suffered from inferiority complex as rehabilitation students. Further, many rehabilitation students thought they were suffering from mental health issues because they were studying rehabilitation. Unsurprisingly, a large number of these subgroup students reported mental health symptoms and suicidal ideation. Our regression models suggested that suicidal ideation is more than two times higher among participants who wanted to leave the profession after completing their degree in a rehabilitation program (study subject‐selection reasons). These subject‐selection reasons explained the higher prevalence rates of suicidal ideation among Bangladeshi students. 11 Additional research is warranted to find in‐depth relations between subject‐related factors and suicidal behavior. Besides subject‐related factors, this study revealed a range of subgroups associated with CMHS and suicidal behavior. In line with the previous study findings, 13 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 this study also found gender, resident type, monthly family income, regular exercise, regular practice of religion, facing hard times and mental health issues, sleeping pill use, sleeping quality, sleeping hour and onscreen time factors were associated with CMHS and suicidal behavior.

A systematic review and meta‐analysis concluded that CMHS undermine suicide globally. 48 A study using the psychological autopsy method in Bangladesh revealed that CMHS was not significantly associated with suicide among the younger population. However, CMHS was associated with older adults' suicide. 49 A case‐control psychological autopsy study conducted in Bangladesh suggested that psychological disorders, immediate life events, and previous suicide attempts were associated with suicide. 50 Our study found that depression and stress symptoms significantly predicted suicidal thought; however, only stress symptoms significantly predicted suicide attempt(s). In line with our findings, a recent study found that depression and stress were significantly associated with suicidal behavior among Chinese university students. 51 Additionally, a 2017 systematic review and meta‐analysis also suggested that depression was associated with suicidal behavior among university students. 52

Recent systematic reviews and meta‐analyses suggested that the prevalence of COVID‐19 pandemic time CMHS and suicidal behavior was higher among different cohorts worldwide. 12 , 53 Previous studies have found the association between COVID‐19 related factors and CMHS and suicidal behavior among students and young adults in Bangladesh. 54 , 55 Furthermore, another systematic review and meta‐analysis confirmed that COVID‐19 related factors were associated with suicidal behavior among Bangladeshi. 56 However, we did not find a significant association between COVID‐19 related factors and CMHS and suicidal behavior among rehabilitation students. Subject‐related factors might outweigh the impact of COVID‐19 among this cohort. Additional study is warranted to find the in‐depth relation between COVID‐19 related factors, subject related factors, and CMHS and suicidal behavior among rehabilitation students in Bangladesh.

Universal limitations of cross‐sectional study and methods bias of self‐reported data collection must be recognized for this study. We did not take the participants' family history of mental health symptoms and suicidal behavior that could confound the result in this study. Data regarding substance abuse could further strengthen the study result. Additionally, limitations of subjective questions used in this study must be acknowledged. Despite these limitations, this study sets baseline evidence from a lower‐middle‐income country regarding the prevalence and predicting factors for CMHS and suicidal behavior among rehabilitation students.

5. CONCLUSION

This study reported a significantly high prevalence of CHMS and suicidal behavior among Bangladesh's relatively less prioritized student cohort. Sociodemographic factors, illness, behavior, institution, and subject‐related issues were identified as the predicting factors of CMHS and suicidal behavior. To deal with CHMS and suicide risk, a holistic, supportive approach from government and academic institutions is essential to reduce this study's identified predicting factors. Implementing appropriate government regulation on the rehabilitation profession can ensure career dignity, social status, and better job opportunities, which helps minimize CHMS and suicide risk.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures were approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Uttara Adhunik Medical College and Hospital (UAMC‐IRB‐2020/12). Prospective observational trial registration was obtained from the World Health Organization endorsed Clinical Trial Registry‐CTRI/2021/01/030297 (Registered on January 6, 2021). The study was conducted following the Helsinki declaration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mohammad Ali: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; writing–original draft. Funding acquisition: Not applicable. Mohammad Ali, Zakir Uddin, Kazi M. Amran Hossain, Turjo Rafid Uddin: Resources; writing–review and editing. Zakir Uddin: Supervision. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Dr. Mohammad Ali had full access to all the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All the authors acknowledge the participants for providing us the information to conduct the study. The authors also thank the institution offices and those who provided email addresses and helped in the data collection process.

Ali M, Uddin Z, Amran Hossain KM, Uddin TR. Depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal behavior among Bangladeshi undergraduate rehabilitation students: an observational study amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5:e549. 10.1002/hsr2.549

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data were available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jesus TS, Landry MD, Dussault G, Fronteira I. Human resources for health (and rehabilitation): six rehab‐workforce challenges for the century. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mamin FA, Hayes R. Physiotherapy in Bangladesh: inequality begets inequality. Front Public Health. 2018;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy . World Confederation for Physical Therapy. June 27, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.wcpt.org/node/25749

- 4. World Federation of Occupational Therapists . Available from: https://www.wfot.org/member-organisations/bangladesh-bangladesh-occupational-therapy-association

- 5. Jesus TS, Koh G, Landry M, et al. Finding the “Right‐Size” Physical Therapy Workforce: international perspective across 4 countries. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1597‐1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali M, Uddin Z, Hossain A. Economic stressors and mental health symptoms among Bangladeshi rehabilitation professionals: a cross‐sectional study amid COVID‐19 pandemic. Heliyon. 2021;7(4):e06715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization . World report on disability who library cataloguing‐in‐publication data [Internet]. April 22, 2021. Accessed April 1, 2021. www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html

- 8. El‐Saharty S, Ahsan KZ, Koehlmoos TLP & Engelgau MM Tackling Noncommunicable Diseases in Bangladesh: now is the Time. Directions in Development—Human Development, Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/15784

- 9. Bangladesh Society of Medicine . Noncommunicable disease risk factor survey Bangladesh 2010; 2011.

- 10. Mamun MA, Hossain MS, Griffiths MD. Mental health problems and associated predictors among Bangladeshi students. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019:1‐15. 10.1007/s11469-019-00144-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakib N, Islam M, Al Habib MS, et al. Depression and suicidality among Bangladeshi students: subject selection reasons and learning environment as potential risk factors. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2020;57(3):1150‐1162. 10.1111/ppc.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang JJ, Ji Y, Li YH, Pan HF, Su PY. Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students during COVID‐19 pandemic: a meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:242‐254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Islam M, Sujan SH, Tasnim R, Sikder T, Potenza M, van Os J. Psychological responses during the COVID‐19 outbreak among university students in Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0245083. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brådvik L. Suicide risk and mental disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Milner A, Page A, LaMontagne AD. Long‐term unemployment and suicide: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e51333. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milner A, Witt K, LaMontagne AD, Niedhammer I. Psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: a meta‐analysis and systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(4):245‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1425. Available from: www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shah MMA, Ahmed S, Arafat SMY. Demography and risk factors of suicide in bangladesh: a six‐month paper content analysis. Psychiatry J. 2017;2017:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arafat SMY, Al Mamun MA. Repeated suicides in the University of Dhaka (November 2018): strategies to identify risky individuals. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;39:84‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mamun MA, Misti JM, Griffiths MD. Suicide of Bangladeshi medical students: risk factor trends based on Bangladeshi press reports. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;48:101905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Syed A, Syed SA, Khan M. Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among the undergraduate physiotherapy students. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2018;34(2):468‐471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali M, Hossain A. What is the extent of COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? A cross‐sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e050303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alim SAHM, Kibria SME, Lslam MJ, et al. Translation of DASS 21 into Bangla and validation among medical students. Bangladesh J Psychiatry. 2017;28(2):67‐70. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Turecki G, Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet. 2016;387:1227‐1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu H, Qin L, Wang J, et al. A cross‐sectional study on risk factors and their interactions with suicidal ideation among the elderly in rural communities of Hunan, China. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010914. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rafi MA, Mamun MA, Hsan K, Hossain M, Gozal D. Psychological implications of unemployment among Bangladesh Civil Service job seekers: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:578. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00578/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mamun MA, Akter S, Hossain I, et al. Financial threat, hardship and distress predict depression, anxiety and stress among the unemployed youths: a Bangladeshi multi‐city study. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:1149‐1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Puthran R, Zhang MWB, Tam WW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta‐analysis. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):456‐468. 10.1111/medu.12962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quek TTC, Tam WWS, Tran BX, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta‐analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hossain MM, Rahman M, Trisha NF, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Heliyon. 2021;7(4):e06677. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Safa F, Anjum A, Hossain S, et al. Immediate psychological responses during the initial period of the COVID‐19 pandemic among Bangladeshi medical students. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;122:105912. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chaudhuri A, Mondal T, Goswami A. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students in a developing country during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a pilot study. J Sci Soc. 2020;47(3):158‐163. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Halperin SJ, Henderson MN, Prenner S, Grauer JN. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:238212052199115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hossain MD, Ahmed HU, Chowdhury WA, Niessen LW, Alam DS. Mental disorders in Bangladesh: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):216. 10.1186/s12888-014-0216-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214‐2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mamun MA, Rayhan I, Akter K, Griffiths MD. Prevalence and predisposing factors of suicidal ideation among the university students in Bangladesh: a single‐site survey. J Ment Health Addict. 2020; 10.1007/s11469-020-00403-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheung T, Lam SC, Lee PH, Xiang YT, Yip PSF. Global imperative of suicidal ideation in 10 countries amid the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:588781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(2):229‐238. 10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tasnim R, Islam MS, Sujan MSH, Sikder MT, Potenza MN. Suicidal ideation among Bangladeshi university students early during the COVID‐19 pandemic: prevalence estimates and correlates. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105703. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mamun MA, Akter T, Zohra F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of COVID‐19 suicidal behavior in Bangladeshi population: are healthcare professionals at greater risk? Heliyon. 2020;6(10):e05259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Solomou I, Constantinidou F. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID‐19 pandemic and compliance with precautionary measures: age and sex matter. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ali M, Ahsan GU, Khan R, Khan HR, Hossain A. Immediate impact of stay‐at‐home orders to control COVID‐19 transmission on mental well‐being in Bangladeshi adults: patterns, explanations, and future directions. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Faisal RA, Jobe MC, Ahmed O, Sharker T. Mental health status, anxiety, and depression levels of Bangladeshi university students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Ment Health Addict. 2021. 10.1007/s11469-020-00458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arusha AR, Biswas RK. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression due to examination in Bangladeshi youths: a pilot study. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116:105254. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Islam MA, Barna SD, Raihan H, Khan MNA, Hossain MT. Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a web‐based cross‐sectional survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238162. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Basheti IA, Mhaidat QN, Mhaidat HN. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during COVID‐19 pandemic among healthcare students in Jordan and its effect on their learning process: a national survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249716. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mamun MA, Misti JM, Hosen I, Mamun F. Suicidal behaviors and university entrance test‐related factors: a Bangladeshi exploratory study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2022;58:(1):278–287. 10.1111/ppc.12783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Too LS, Spittal MJ, Bugeja L, Reifels L, Butterworth P, Pirkis J. The association between mental disorders and suicide: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of record linkage studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:302‐313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arafat SMY, Mohit MA, Mullick MSI, Khan MAS, Khan MM. Suicide with and without mental disorders: findings from psychological autopsy study in Bangladesh. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;61:102690. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arafat SMY, Mohit MA, Mullick MSI, Kabir R, Khan MM. Risk factors for suicide in Bangladesh: case–control psychological autopsy study. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(1):e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, et al. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well‐being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0217372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang YH, Shi ZT, Luo QY. Association of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among university students in China: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(13):e6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Farooq S, Tunmore J, Ali W, Ayub M. Suicide, self‐harm and suicidal ideation during COVID‐19: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021;306:114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hosen I, Al Mamun F, Mamun MA. The role of sociodemographics, behavioral factors, and internet use behaviors in students' psychological health amid COVID‐19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heal Sci Reports. 2021;4(4):e398. 10.1002/hsr2.398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mamun MA, Al Mamun F, Hosen I, et al. Suicidality in Bangladeshi young adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic: the role of behavioral factors, COVID‐19 risk and fear, and mental health problems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:4051‐4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mamun MA. Suicide and suicidal behaviors in the context of COVID‐19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a systematic review. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:695‐704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data were available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.