Abstract

Although studies have investigated the association between conventional tobacco smoking and mental outcomes among adolescents in the United States, few studies have examined the association between electronic vaping products (EVPs) and mental health among adolescents. This study aimed to investigate the cross-sectional association between EVPs use, symptoms of depression, and suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Data were pooled from the 2017 and 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. An analytic sample of 14,285 adolescents (50.3% female) was analyzed using binary logistic regression. The outcome variables investigated were symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempts, and the main explanatory variable was EVPs use. Of the 14,285 adolescents, 22.2%, 19.2%, and 58.8% were current, former and never users of EVPs, respectively. Controlling for other factors, current users of EVPs were significantly more likely to report having symptoms of depression (AOR=1.82, 95% CI=1.58-2.09), having suicidal ideation (AOR=1.55, 95% CI=1.30-1.86), making a suicide plan (AOR=1.62, 95% CI=1.34-1.97), or attempting suicide (AOR=1.75, 95% CI=1.41-2.18) when compared to never users of EVPs. Sex moderated the association between EVPs use, symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide plan. Racial minority identity, sexual minority identity, sexual violence victimization, victim of school and cyberbullying, alcohol use, and cigarette smoking were all significantly associated with depression and suicidal behaviors. Study findings support the association between EVPs use and adolescent mental health. Future studies that employ longitudinal designs may offer more insight into the mechanisms underlying this association.

Keywords: Electronic vaping products, mental health, symptoms of depression, suicidal behaviors, sex differences, adolescents

1. Introduction

Depression and suicidal behaviors, which includes suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempts, are common mental health problems experienced by adolescents in the United States (U.S.; Mojtabai et al., 2016; Rockett et al., 2016). Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 13-19 years in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). A significant risk factor for death by suicide is a prior suicide attempt (Bridge et al., 2006). Data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) shows that about one in three adolescent high school students in the U.S. experienced symptoms of depression, 18.8% experienced suicidal ideation, 15.7% made a suicide plan, and 8.9% attempted suicide at least once in 2019 (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020).

The age of onset for these mental health problems is often early in life. Kessler et al. (2005) found that nearly half of all mental health problems start by age 14 and 75% by age 24. Depression can have a significant deleterious impact on overall well-being and can lead to engagement in suicidal behaviors (Baiden et al., 2017; Hirdes et al., 2020). Early identification and treatment of mental health can help prevent future problems (Hirdes et al., 2020).

Past studies suggest a significant association between cigarette smoking, symptoms of depression, and suicidal behaviors (Gart & Kelly, 2015; Kahn & Wilcox, 2020; Ranjit, Buchwald, et al., 2019). For example, Ranjit, Buchwald, et al. (2019) found that cigarette smoking at age 14 significantly predicted depressive symptoms at age 17. Additionally, Dasagi et al. (2021) found that adolescents who engaged in heavy cigarette smoking (smoking 11 or more cigarettes per day) were 3.43 times more likely to report symptoms of depression, 2.97 times more likely to report suicidal ideation, and 2.11 times more likely to report ever planning a suicide attempt.

In 2007, electronic vaping products (EVPs) entered the U.S. market advertised as a less harmful alternative to cigarettes (Sen Choudhury, 2021). Since, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of EVPs use among adolescents (Chen-Sankey et al., 2019; Niaura et al., 2014). Data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study showed that in 2015, EVPs had the highest 30-day prevalence of all tobacco products among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders (Miech et al., 2016). Possible reasons for the increase in use of EVPs include that they are considered less harmful than conventional cigarettes (Nutt et al., 2016), less stigmatized (Martinez et al., 2018; Tokle & Pedersen, 2019), and come in different flavors (Sen Choudhury, 2021; Tsai et al., 2018).

The extant literature has found sex differences in patterns of EVPs use (Buu et al., 2020; Wong & Fan, 2018; Yimsaard et al., 2021). For instance, some studies have found that compared to males, females tend to prefer EVPs that resemble cigarettes (Dawkins et al., 2013) and are more likely to use EVPs that are sweet and fruit-flavored (Bunch et al., 2018) or have a non-tobacco flavor and lower nicotine strength (Pineiro et al., 2016). Other studies, however, have found that males are more likely to prefer tobacco-flavored EVPs (Pineiro et al., 2016). Understanding sex differences in the use of EVPs is important given that research has found that the type of EVPs device and content may affect patterns of EVPs use (Yamsaard et al., 2021). Such an understanding may also have implications for the utility of EVPs as nicotine replacement. Previous studies have also found sex differences in reasons for the use of EVPs. For instance, some scholars have found that whereas females are more likely to report continuing use of EVPs to deal with stress, males are more likely to report continuing use of EVPs to help cut down smoking and for enjoyment (Pineiro et al., 2016). In addition, previous research has linked EVPs use to weight management among females (Jackson et al., 2019), although at least one published study found no sex differences in EVPs use for weight management (Morean & Wedel, 2017).

Research suggests that individuals who engage in the use of EVPs are more likely to have a history of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems (Buu et al., 2020; Chun et al., 2020). For instance, Buu et al. (2020) examined data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (PATH) and found that internalizing (e.g., depression and anxiety) and externalizing (e.g., aggression and delinquency) behavior problems at Wave 1 significantly predicted the initiation and progression of use of EVPs at Wave 2. However, there is a dearth of studies examining the association between use of EVPs and mental health including suicidal behaviors among adolescents in the U.S. (Chadi et al., 2019; Eberlein et al., 2014). The increasing use of EVPs among adolescents (Chen-Sankey et al., 2019; Miech et al., 2016; Niaura et al., 2014) and the association of cigarette smoking with depression and suicidal ideation (Gart & Kelly, 2015; Kahn & Wilcox, 2020) warrant further investigation of this phenomenon.

Scholars hypothesized that adolescents who experienced depression and/or suicidal behaviors may use EVPs to self-soothe, and that adolescents who use EVPs experience other risk factors such as sexual violence or bullying victimization, both of which have been found to significantly predict depression and suicidal behaviors (Chadi et al., 2019; Sen Choudhury, 2021). Drawing from self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1997), some scholars have maintained that substance use, including use of EVPs, may be part of an individual’s response to emotional or psychological distress, oftentimes arising from past traumatic experiences (Maniglio, 2015, 2017; Stewart et al., 2013). Melka et al. (2019) examined data from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health and found that women who experienced sexual abuse before aged 16 years were 1.4 times more likely to report the use of EVPs at aged 26 when compared to their non-abused counterparts. In the U.S., Doxbeck et al. (2021) examined data from the 2017 YRBS and found that history of sexual violence had a significant direct effect on use of EVPs. Analyzing data from the 2016-2017 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, Azagba et a. (2019) also found that school bullying victimization was significantly associated with higher odds of use of any EVPs. Doxbeck (2020) further found that controlling for demographic factors and other substance use behaviors, adolescents who were victims of school bullying or cyberbullying were significantly more likely to report using EVPs during the past 30 days when compared to their counterparts who were not victimized. Taken together, the findings from these studies suggest that adolescents with a history of sexual violence or who were victims of bullying may resort to the use of EVPs as means of self-soothing past traumatic experiences.

Other factors associated with mental health and suicidal behaviors among adolescents include sexual violence victimization, school bullying and cyberbullying victimization, and alcohol and cigarette use. Analyzing data from the Add Health study, Thompson et al. (2019) found that adolescents with a history of sexual violence had between 1.4 to 2.7 times increased odds of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adulthood. Experiencing sexual violence may increase the victim’s ability to habituate to pain, thereby acclimatizing them to the fear associated with bodily injury and increasing their capability for lethal self-harm (Van Orden et al., 2010). Other scholars have also maintained that notwithstanding the fact that sexual violence victimization is more common among females, males who experience sexual violence may face additional stigma given norms around masculinity and disclosure of sexual abuse (Javaid, 2018); potentially exacerbating feelings of burdensomeness or thwarted belonging - two critical risk factors for a suicide attempt as demonstrated by the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005). School bullying and cyberbullying victimization have also been found to significantly predict symptoms of depression (Baiden et al., 2017) and suicidal behaviors (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2016). Various meta-analytic studies have found a significant association between school bullying and cyberbullying victimization and the onset of depressive symptoms (Kowalski et al., 2014; Modecki et al., 2014; Ttofi et al., 2014; Zych et al., 2019).

Demographic factors such as sex, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity have all been found to be associated with poor mental health and suicidal behaviors. Compared to adolescent males, adolescent females are more likely to experience suicidal ideation and attempt suicide (Felez-Nobrega et al., 2020; Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019). Some scholars have attributed the higher prevalence of suicidal behaviors among adolescent girls to biological transition and pubertal onset, which occurs on average earlier for girls than for boys (Lee et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2020). Depressive symptomatology which is one of the strongest predictors of suicidal behaviors (Nock et al., 2008), is also known to increase more quickly for girls during adolescence than for boys (Adrian et al., 2016; Boeninger et al., 2010). Available literature also suggests that victimization related experiences such as school bullying and cyberbullying significantly predisposes sexual minority youth to experience mental health problems such as depression (Mustanski et al., 2016; Veale et al., 2017), and engaging in suicidal behaviors (Hatchel et al., 2019). With respect to race/ethnicity, some scholars have found that whereas Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) and Hispanic adolescents are less likely to experience mental health problems and engage in suicidal ideation than their White counterparts, BIPOC adolescents are more likely to make a suicide attempt when compared to their White counterparts (Kann et al., 2018). A systematic review by Colucci and Martin (2007) also found a higher prevalence of suicide attempts among adolescent Black males relative to their White male counterparts.

1.1. Current study

Few studies in the U.S. have utilized large nationally representative cohort data to examine the associations between EVPs use and adolescent mental health outcomes (Becker et al., 2021). Relevant studies are limited to less up-to-date samples, and do not examine former EVPs users and suicidal behaviors besides suicidal ideation (Chadi et al., 2019). Identification of former EVPs users may contribute to a more nuanced understanding of who is at risk for mental health problems. For example, reports of making a suicide plan and/or attempting suicide demonstrate an elevated suicide risk (Nock et al., 2008). Lastly, research is needed to explore gender differences regarding the association between EVPs and mental health outcomes, as adolescent females are more likely than males to report symptoms of depression (Geiger & Davis, 2019) and engage in suicidal behaviors (Baiden et al., 2020; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020; Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019).

Informed by frameworks from the fields of substance use (Khantzian, 1997) and suicide research (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010), this study seeks to extend the existing literature by drawing on a large nationally representative sample of adolescents in the U.S. to examine the cross-sectional association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors. We hypothesized that controlling for the effects of known risk factors for depression and suicidal behaviors, there would be an association between EVPs and symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempts. We further hypothesized that the association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors would depend on gender.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data for this study were obtained from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The YRBS is a cross-sectional school-based national survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) every two years to examine health-risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death and disability among youth in grades 9 to 12 in the U.S. The objectives, methodology, and sampling procedure for the YRBS have been described elsewhere (Brener et al., 2013; Kann et al., 2018; Underwood et al., 2020). In brief, the YRBS utilized a three-stage cluster sample design to recruit 9th to 12th graders from both public and private schools to complete self-administered surveys. A nationally representative sample of schools and a random sample of classes within those schools were selected to participate in the 2017 and 2019 YRBS. First, schools were selected systematically with probability proportional to enrollment in grades 9 through 12 using a random start from primary sampling units (PSUs), made up of entire counties, groups of smaller adjacent counties, or parts of larger counties. PSUs were categorized into different strata based on their metropolitan statistical area status (e.g., urban or rural) and the percentages of non-Hispanic Black (Black) and Hispanic students in each PSU. For the second-stage sampling, secondary sampling units were sampled with probability proportional to school enrollment size. The third and final stage of sampling comprised of a random sampling of one or two classrooms in grades 9 through 12 from either a required subject (e.g., English or social studies) or a required period (e.g., homeroom or second period). All students in sampled classes were eligible to participate. Schools, classes, and students who refused to participate were not replaced in the sampling design. The YRBS dataset have been used in several studies and the measures have been found to have strong psychometric properties (Brener et al., 2013). The YRBS was approved by the CDC’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), and the de-identified data are publicly available. The current study was exempted from IRB approval by the lead author’s institution as the data had already been de-identified and did not contain any personally identifying information. We followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines in the conduct of this study (Von Elm et al., 2007).

2.2. Sample

For the purposes of this study, data from high school students from the 2017 and 2019 national YRBS were combined to obtain a sufficient sample size. The resulting sample size for the combined 2017 and 2019 national YRBS was 28,442 high school students. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion of cases. Imputation of missing data is not recommended for studies using the YRBS (Brener et al., 2013); hence, the analyses presented in this study were restricted to adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18 years and had complete data on all the variables included in the analysis. This resulted in a final analytic sample of n = 14,285.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Outcome variables

The outcome variables examined in this study included symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempt and were measured as binary variables. Symptoms of depression were measured based on the question, “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” Adolescents who answered “yes” were coded as 1, whereas those who answered “no” were coded as 0. Suicidal ideation was measured based on response to the question, “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” Adolescents who answered “yes” were coded 1, whereas adolescents who answered “no” were coded 0. Suicide plan was measured based on response to the question, “During the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?” Adolescents who answered “yes” were coded 1, whereas adolescents who answered “no” were coded 0. Suicide attempt was measured based on response to the question, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” Adolescents who attempted suicide at least once during the past 12 months were coded as 1, whereas adolescents who did not attempt suicide during the past 12 months were coded as 0.

2.3.2. Explanatory variable

The main explanatory variable examined in this study was the use of EVPs and was defined to include e-cigarettes, vapes, vape pens, e-cigars, e-hookahs, hookah pens, and mods. EVPs was measured as an ordinal variable using two questions: 1) Have you ever used an electronic vapor product, and 2) During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use an electronic vapor product? Adolescents who have never used EVPs were coded as 0. Adolescents who reported ever using EVPs but not within the past 30 days were considered former users and coded as 1. Adolescents who reported using EVPs within the past 30 days were considered current users and coded as 2.

2.3.3. Covariates

Covariates examined included victims of sexual violence (SV), school bullying, cyberbullying, current cigarette smoking, and current alcohol use. In addition, the following demographic variables were also included as control variables, age, race, gender, and sexual orientation. The specific variables, survey questions used, and coding used for the statistical analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of demographic variables and covariates derived from the 2017 and 2019 national YRBS

| Variable name | Survey question | Analytic coding |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | What is your sex? | 0 = Male 1= Female |

| Age | How old are you? | 12–18 years |

| Race | What is your race | 0 = non-Hispanic White 1 = Black/African American 2 = Hispanic 3 = Othersa |

| Sexual orientation | Which of the following best describes you? | 0 = Straight 1 = Lesbian/gay 2 = Bisexual 3 = Not sure |

| Victim of school bullying | During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property? | 0 = No vs. 1 = Yes |

| Victim of cyberbullying | During the past 12 months, have you ever been electronically bullied? (Count being bullied through texting, Instagram, Facebook, or other social media). | 0 = No vs. 1 = Yes |

| Cigarette smoking | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes? | 0 = 0 days vs. 1 or more days |

| Alcohol use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol? | 0 = 0 days vs. 1 or more days |

| Victim of sexual violence | During the past 12 months, how many times did anyone force you to do sexual things that you did not want to do?” (Count such things as kissing, touching, or being physically forced to have sexual intercourse) | 0 = 0 times vs. 1 or more times |

Adolescents who did not identify primarily with one of the three racial/ethnic categories provided (i.e., Non-Hispanic White, Black/African American, or Hispanic).

2.4. Data analyses

Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate analytic techniques were employed. First, the general distribution of all the variables included in the analysis was examined using frequencies and percentages. The association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors was then examined using Pearson chi-square test of association. The main analysis involves using binary logistic regression to examine the association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors while controlling for other covariates and demographic factors. To examine whether the association between use of EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors is dependent on gender, a two-way interaction term between use of EVPs and gender was examined. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) are reported together with their 95% Confidence Intervals (C.I.). Variables were considered significant if the p-value was less than .05. Stata’s “svyset” command was used to account for the weighting and complexity of the cluster sampling design employed by the YRBS. All analyses are based on the weighted data were performed using STATA version 15 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Table 2 below shows the general distribution of the study variables. Of the 14,285 adolescents, 22.2% currently use EVPs, 19.2% formerly used EVPs, and 58.8% have never used EVPs. In 2017, 66% of adolescents never used EVPs compared to 52% of adolescents who never used EVPs in 2019, and 22% of adolescents were former users of EVPs in 2017 compared to 16.1% of adolescents who were former users of EVPs in 2019. About 12% of adolescents currently use EVPs in 2017 compared to 32% of adolescents who currently use EVPs in 2019. About one in three adolescents (33.7%) had symptoms of depression, 18% reported experiencing suicidal ideation, 14% made a suicide plan, and 6.6% attempted suicide during the past 12 months. The sample was evenly distributed by gender (50.3% female). See Table 2 for the distribution of the other variables.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (N = 14,285)

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Outcome variables | |

| Symptoms of depression | |

| No | 9472 (66.3) |

| Yes | 4813 (33.7) |

| Suicidal ideation | |

| No | 11,780 (82.5) |

| Yes | 2,505 (17.5) |

| Suicide plan | |

| No | 12,288 (86.0) |

| Yes | 1,997 (14.0) |

| Suicide attempts | |

| No | 13,346 (93.4) |

| Yes | 939 (6.6) |

| Main explanatory variable | |

| Use of electronic vaping products | |

| Never | 8,397 (58.8) |

| Former user | 2,745 (19.2) |

| Current use | 3,143 (22.0) |

| Control variables | |

| Age | |

| 14 years | 1,633 (11.4) |

| 15 years | 3,589 (25.1) |

| 16 years | 3,644 (25.5) |

| 17 years | 3,483 (24.4) |

| 18 years or older | 1,936 (13.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7,095 (49.7) |

| Female | 7,190 (50.3) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight | 12,242 (85.7) |

| Lesbian/gay | 327 (2.3) |

| Bisexual | 1,163 (8.1) |

| Unsure | 553 (3.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 8,049 (56.3) |

| Black/African American | 1,309 (9.2) |

| Hispanic | 3,358 (23.5) |

| Other | 1,569 (11.0) |

| Victim of sexual violence | |

| No | 12,982 (90.9) |

| Yes | 1,303 (9.1) |

| Victim of school bullying | |

| No | 11,631 (81.4) |

| Yes | 2,654 (18.6) |

| Victim of cyberbullying | |

| No | 12,196 (85.3) |

| Yes | 2,089 (14.6) |

| Currently smoke cigarette | |

| No | 13242 (92.7) |

| Yes | 1043 (7.3) |

| Currently drinks alcohol | |

| No | 10,238 (71.7) |

| Yes | 4,047 (28.3) |

3.2. Bivariate association between EVPs and suicidal behaviors

As seen in Table 3, there was a significant bivariate association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors. Close to one in two adolescents (47%) who currently use EVPs had symptoms of depression compared to 38.3% of former users, and 27.3% of those who have never used EVPs (χ2(2) = 431.05, p<.001). More than one in four adolescents (26.1%) who currently use EVPs compared to one in five (19.9%) who are former users, and 13.6% of those who have never used EVPs experienced suicidal ideation (χ2(2) = 262.57, p<.001). Similarly, about 21% of adolescents who currently use EVPs compared to 16.9% of adolescents who are former users, and 10.3% of those who have never used EVPs made a suicide plan (χ2(2) = 252.73, p<.001). About 12% of adolescents who currently use EVPs compared to 7.6% of adolescents who are former users, and 4.3% of adolescents who have never used EVPs attempted suicide (χ2(2) = 212.60, p<.001).

Table 3.

Use of electronic vaping products by suicidal Behaviors (N = 14,285)

| Outcome variables | Use of electronic vaping products | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (%) |

Former user (%) |

Current user (%) |

χ2 value | |

| Symptoms of depression | 431.05 (p < .001) | |||

| No | 72.8 | 61.7 | 53.0 | |

| Yes | 27.2 | 38.3 | 47.0 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 262.57 (p < .001) | |||

| No | 86.4 | 80.1 | 73.9 | |

| Yes | 13.6 | 19.9 | 26.1 | |

| Suicide plan | 252.73 (p < .001) | |||

| No | 89.7 | 83.1 | 78.7 | |

| Yes | 10.3 | 16.9 | 21.3 | |

| Suicide attempt | 212.60 (p < .001) | |||

| No | 95.7 | 92.4 | 88.3 | |

| Yes | 4.3 | 7.6 | 11.7 | |

3.3. Logistic regression results examining the association between EVPs and suicidal behaviors

Table 4 shows the multivariable logistic regression results of the association between EVPs and symptoms of depression and the three suicidal behaviors. When controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to violence, and substance use, there was a significant association between EVPs and the four outcome variables. Compared to adolescents who have never used EVPs, adolescents who currently use EVPs are more likely to report having symptoms of depression (AOR=1.82, p<.001, 95% CI=1.58-2.09), suicidal ideation (AOR=1.55, p<.001, 95% CI=1.30-1.86), making a suicide plan (AOR=1.62, p<.001, 95% CI=1.34-1.97), and attempting suicide (AOR=1.75, p<.001, 95% CI=1.41-2.18). Adolescents who formerly used EVPs are more likely to report having symptoms of depression (AOR=1.42, p<.001, 95% CI=1.25-1.62), experiencing suicidal ideation, (AOR=1.32, p<.001, 95% CI=1.12-1.56), making a suicide plan (AOR=1.48, p<.005, 95% CI=1.22-1.79), and attempting suicide attempt (AOR=1.44, p=.003, 95% CI=1.13-1.83) when compared to their counterparts who have never used EVPs.

Table 4:

Multivariate logistic regression results predicting suicidal behaviors (N = 14,285)

| Variables | Symptoms of depression |

Suicidal ideation | Suicide plan | Suicide attempts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% C.I.) |

p- value |

AOR (95% C.I.) |

p- value |

AOR (95% C.I.) |

p- value |

AOR (95% C.I.) |

p- value |

|

| Use of electronic vaping products (Never) | ||||||||

| Former user | 1.42 (1.25-1.62) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.12-1.56) | .001 | 1.48 (1.22-1.79) | <.001 | 1.44 (1.13-1.83) | .003 |

| Current user | 1.82 (1.58-2.09) | <.001 | 1.55 (1.30-1.86) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.34-1.97) | <.001 | 1.75 (1.41-2.18) | <.001 |

| Age in years | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | .273 | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | .663 | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) | .519 | 0.88 (0.81-0.95) | .002 |

| Gender (Male) | ||||||||

| Female | 1.82 (1.61-2.05) | .001 | 1.33 (1.14-1.54) | <.001 | 1.23 (1.06-1.44) | .008 | 1.22 (0.96-1.57) | .109 |

| Sexual orientation (Straight) | ||||||||

| Lesbian/gay | 3.15 (2.30-4.31) | .001 | 4.58 (3.54-5.92) | <.001 | 3.76 (2.89-4.89) | <.001 | 2.66 (1.83-3.87) | <.001 |

| Bisexual | 3.55 (3.04-4.14) | .001 | 5.12 (4.41-6.17) | <.001 | 4.65 (3.89-5.56) | <.001 | 3.65 (2.86-4.67) | <.001 |

| Unsure | 2.00 (1.52-2.63) | .001 | 2.80 (2.15-3.64) | <.001 | 2.79 (2.19-3.56) | <.001 | 1.81 (1.30-2.51) | .001 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White) | ||||||||

| Black/African American | 1.02 (0.85-1.22) | .852 | 1.02 (0.81-1.28) | .891 | 1.09 (0.81-1.46) | .577 | 1.81 (1.27-2.57) | .001 |

| Hispanic | 1.46 (1.28-1.66) | .001 | 0.98 (0.85-1.12) | .743 | 1.13 (0.97-1.31) | .115 | 1.35 (1.04-1.74) | .023 |

| Other | 1.46 (1.27-1.69) | .001 | 1.54 (1.27-1.87) | <.001 | 1.70 (1.40-2.07) | <.001 | 1.97 (1.61-2.41) | <.001 |

| Victim of sexual violence (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.78 (2.41-3.21) | .001 | 2.32 (1.92-2.79) | <.001 | 2.37 (1.92-2.92) | <.001 | 2.74 (2.12-3.53) | <.001 |

| Victim of school bullying (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.35 (2.07-2.66) | .001 | 2.31 (2.00-2.66) | <.001 | 2.16 (1.82-2.55) | <.001 | 2.32 (1.81-2.97) | <.001 |

| Victim of cyberbullying (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.85 (1.62-2.10) | .001 | 1.55 (1.33-1.82) | <.001 | 1.51 (1.25-1.82) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.39-2.38) | <.001 |

| Currently drinks alcohol (No) | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.24 (1.08-1.43) | .003 | 1.25 (1.05-1.50) | .014 | 1.26 (1.05-1.52) | .013 | 1.19 (0.93-1.53) | .163 |

| Current cigarette use (No | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.20 (0.96-1.49) | .106 | 1.51 (1.20-1.91) | .001 | 1.39 (1.05-1.82) | .021 | 2.09 (1.66-2.63) | <.001 |

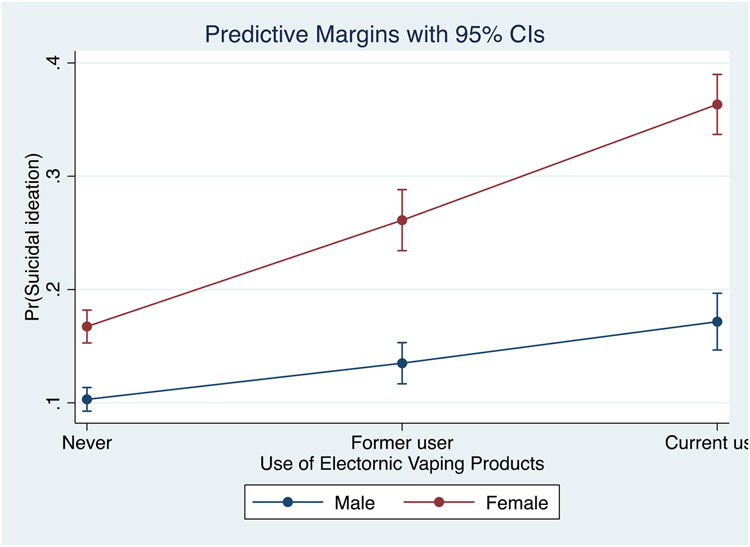

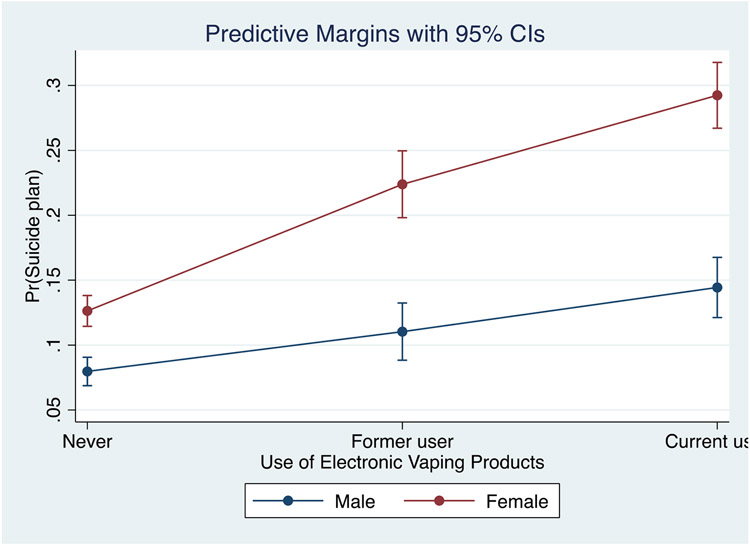

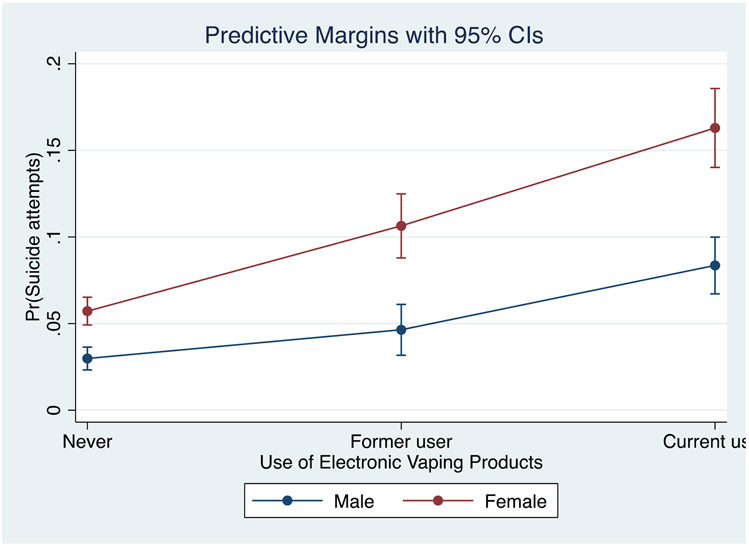

To examine whether the association between EVPs and the four outcome variables is dependent on gender, we conducted a two-way interaction between EVPs and gender. The results presented in Table 5 shows that there was a significant interaction effect between EVPs and gender on symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide plan. However, there was no significant interaction effect between EVPs and gender on suicide attempts. Adolescent females who currently use EVPs had 1.51 times higher odds of experiencing symptoms of depression (AOR=1.51, p<.001, 95% CI=1.21-1.90), 1.49 times higher odds of experiencing suicidal ideation (AOR=1.49, p<.001, 95% CI=1.14-1.94), and 1.35 times higher odds of making a suicide plan (AOR=1.35, p=.048, 95% CI=1.01-1.83) when compared to adolescent males who currently use EVPs. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the predictive margins plot of the interaction between gender and EVPs use for suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempts, respectively.

Table 5:

Interaction between EVPs and gender in predicting suicidal behaviors (N = 14,285)

| Variables | Symptoms of depression | Suicidal ideation | Suicide plan | Suicide attempts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | AOR (95% C.I.) | p-value | AOR (95% C.I.) | p-value | AOR (95% C.I.) | p-value | AOR (95% C.I.) | p-value |

| Use of EVPs | ||||||||

| Former user | 1.35 (1.16-1.58) | <.001 | 1.43 (1.17-1.76) | .001 | 1.53 (1.16-2.01) | .003 | 1.79 (1.21-2.66) | .004 |

| Current user | 2.10 (1.78-2.47) | <.001 | 1.97 (1.59-2.45) | <.001 | 2.16 (1.70-2.76) | <.001 | 3.51 (2.63-4.69) | <.001 |

| Gender (Male) | ||||||||

| Female | 1.81 (1.60-2.06) | <.001 | 1.38 (1.16-1.64) | <.001 | 1.31 (1.09-1.56) | .004 | 1.59 (1.22-2.06) | .001 |

| Interaction effects | ||||||||

| Use of EVPs x gender | ||||||||

| Female x Former user | 1.43 (1.13-1.81) | .003 | 1.20 (0.92-1.56) | .167 | 1.30 (0.96-1.75) | .086 | 1.08 (0.67-1.75) | .738 |

| Female x Current user | 1.51 (1.21-1.90) | <.001 | 1.49 (1.14-1.94) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.01-1.83) | .048 | 0.96 (0.67-1.37) | .798 |

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities for the interaction between EVPs and gender on suicidal ideation

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities for the interaction between EVPs and gender on suicide plan

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities for the interaction between EVPs and gender on suicide attempts

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to contribute to the literature on the mental health effects of EVPs use among adolescents. The findings of this study suggest that EVPs use is associated with symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide plan among adolescents and that these associations were stronger for adolescent females. Our finding that more than one in five adolescents reports current use of EVPs is remarkably higher than prevalence estimates reported in prior studies (Chadi et al., 2019; Dai & Hao, 2017; Riehm et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016), but similar to findings in more recent national assessments (Gentzke et al., 2019). Differences in the operationalization of EVPs and nuances in data collection (pencil/paper versus computer-based) and sampling approaches (household versus school-based) across surveys may account for the disparities in prevalence estimates (Boyd et al., 2020). For instance, Riehm et al. (2019) used data from the 2014 PATH study and measured the use of EVPs and combusted cigarettes from a list of products. Mutually exclusive exposure categories were then generated and coded into 1) exclusive e-cigarette use, 2) exclusive combusted cigarette use, 3) dual-product use, and 4) no use of either product. Riehm et al. (2019) found that 6.3% of adolescents reported exclusive use of EVPs, and 5% reported use of EVPs and combusted cigarettes.

Prior research has found that conventional tobacco smoking is associated with adverse mental health outcomes among adolescents, including depression and suicidal behaviors (Dasagi et al., 2021; Gart & Kelly, 2015; Kahn & Wilcox, 2020; Lawrence et al., 2021; Rodelli et al., 2018). Our findings extend the literature by showing a similar association between EVPs use and mental health indicators. Furthermore, after adjusting for potential confounders, we found that compared to adolescents who have never used EVPs, adolescents who currently use EVPs had elevated odds of reporting worse mental health outcomes (symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors). Past studies on EVPs use and mental health both in the U.S. (Chadi et al., 2019; Lechner et al., 2017; Leventhal et al., 2016) and non-U.S. adolescent populations (Kim & Kim, 2021; Lee & Lee, 2019) have observed similar findings. These findings are further supported by observations in a recent systematic review which shows that EVPs use is associated with mental health problems, particularly among teenagers (Becker et al., 2021). Thus, the association between EVPs use, depressive symptoms, and suicidal behaviors observed in this study are reasons for concern and warrant more research attention.

Although the mechanism through which EVPs use may be associated with depression and suicidal behaviors is less understood, some mechanisms have been hypothesized that may help explain our findings. First, evidence suggests that aerosols, vapor, and other non-nicotine related products contained in EVPs can induce oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory responses, which is highly toxic to the brain (Lerner et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2016), and the developing adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to neurobiological oxidative damage and could result in mental health problems (Cobley et al., 2018; Ikonomidou & Kaindl, 2011). Second, studies show that nicotine uptake into the brain induces hypoxic and oxidative damage, which can result in negative affect, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dysregulation, thereby potentially exacerbating depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors (Ruszkiewicz et al., 2020; Swann et al., 2021; Tobore, 2019). Whereas the neural mechanisms proposed so far remain inconclusive, alarmingly, a growing trend observed in recent literature is that EVPs have emerged as a method of attempting suicide (Jalkanen et al., 2016; Maessen et al., 2020; Park & Min, 2018). Third, other researchers have posited that the association between EVPs and mental health may be more complex and bidirectional, suggesting that poor mental health may lead to a higher likelihood of EVPs use (Bandiera et al., 2017; Lechner et al., 2017). One plausible explanation for this is that adolescents with mental health struggles may use EVPs to self-soothe (Tsai et al., 2018), which aligns with the premise of self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1997). This is further supported by one longitudinal study, which followed 5,455 college students for one year and found that depressive symptoms at Time 1 predicted EVPs use at follow-up (Bandiera et al., 2017). It is also possible that the association between social determinants of health factors such as sexual violence and bullying victimization and mental health and suicidal behaviors may occur through the use of EVPs whereby individuals who have been victimized may resort to the use of EVPs to self-soothe their traumatic experience that they might not be able to control using other means.

Our findings also indicate that gender differences exist in mental health outcomes among adolescent vapers. Adolescent females who currently use EVPs had higher odds of experiencing symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and making a suicide plan when compared to adolescent males who currently use EVPs. Past research on health outcomes among tobacco users in both adolescent and adult populations have shown that females who smoke experience worse overall health outcomes than their male counterparts who smoke (Gold et al., 1996; Holmen et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2012; Sung, 2021; Thompson et al., 2015). One potential mechanism that could explain the poor mental health outcomes among females in our study stems from neurobiological research, which suggests that gender differences in the brain metabolic response to nicotine may affect mood, behavior, and impulsivity, which could predispose females to worse mental health outcomes (Fallon et al., 2005). An additional explanation to the traditionally higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation among adolescent females could be how adolescent females are socialized to respond to emotional distress (e.g., internalizing behaviors) versus adolescent males (e.g., externalizing behaviors) (Bannink et al., 2014; Bor et al., 2014). Thus, as suggested by our findings, current EVPs use among females may serve as an external behavior to signal that a young female is attempting to self-medicate in response to less-visible distress (Bolton et al., 2006; Khantzian, 1997). Given the lack of studies on the gendered differences in mental health outcomes among adolescent EVPs users, our findings extend the limited literature in this area and posit that although EVPs use is associated with depression and suicidal behaviors among adolescents, this association could be worse for females (Lee & Lee, 2019). Thus, public health authorities and policymakers should incorporate gender-specific approaches to combat EVPs use among teenagers. Future studies should also examine whether the mental health effects of EVPs use also differs by race/ethnicity or sexual orientation.

Associations between adolescent demographic characteristics and risk factors and mental health outcomes supported prominent trends in the related literature. Findings suggest that adolescents who identify as a sexual and/or racial/ethnic minority (including those who identify as “other” racially) are overall more likely to report depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors than their heterosexual and non-Hispanic White peers (Hatchel et al., 2019; Kann et al., 2018). Even when controlling for demographic characteristics, participants who experienced sexual violence and school bullying were over two times more likely to report depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors than peers without such experiences (Baiden et al., 2017; Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2016). Both findings support the constructs of the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010), as adolescents who identify as a minority may feel less connected and burdensome to others because of society’s predominantly White heteronormative narrative (Baams et al., 2015; Hollingsworth et al., 2017). Also, adolescents who experience violence and who use substances (another risk factor for mental health outcomes identified in our study) may have a greater acquired capability to attempt suicide (Silva et al., 2015).

4.1. Study Implications

The implications of this study call for additional efforts to prevent or reduce EVPs use among adolescents. School and family health clinics may be ideal settings to extend universal tobacco prevention programs. School staff, pediatricians, and family physicians may play an important role in screening for co-occurring adolescent use of EVPs and mental health needs (Becker et al., 2021; Chadi et al., 2019). Parents and guardians should also be educated on the harmful effects of EVPs on adolescent mental health problems, including offering resources on how and where their children can receive behavioral and mental health services. As demonstrated by our findings, former and current EVPs users will likely require support with both EVPs cessation and emotional distress.

Currently, there are no known effective treatments for adolescent EVPs cessation (Garey et al., 2021). A recent systematic review of published studies on the use of EVPs and mental health among adolescents and young adults noted that although EVPs manufacturers have created brochures to help reduce underage use and misuse, this information has several limitations (Becker et al., 2021). Based on the smoking cessation evidence-based, adapted group-based behavioral interventions may be effective in supporting in-need adolescents (Fanshawe et al., 2017). Parent and school administrator accounts of initiating restrictions of EVPs have been mainly unsuccessful (Chaker, 2018; Zernike, 2019), suggesting that EVPs interventions may function best in a behavioral health setting. The continued promotion of policies that divert EVPs marketing away from younger consumers is also needed (Bhalerao et al., 2019).

4.2. Study Limitations

There are some limitations with this study that are worth noting. First, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to out-of-school adolescents in the U.S., such as home-schooled teenagers and those who frequently skip school, as the sample is made up of school-going adolescents. The use of a school-based sample also suggests that the estimates of EVPs use reported in this study may be underestimated as research has shown that cigarette smoking levels are substantially higher among adolescents who drop out of school (Bachman et al., 2008). Second, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow causal inferences. It is possible that some adolescents may have experienced symptoms of depression or suicidal behaviors prior to them using EVPs. Hence, only an association can be inferred. Longitudinal studies may be more beneficial in establishing directionality and potential causal link between EVPs, depression, and suicidal behaviors. Third, the use of secondary data limits our analysis to variables present in the dataset. Although we adjusted for covariates, we were unable to account for other known risk factors for depression and suicidal behaviors such as family history of mental illness, adverse childhood experiences, parental factors, socioeconomic status, and environmental factors; thus, the potential for bias due to residual confounding could not be eliminated. Also, symptoms of depression and suicidal behaviors were measured using a single item instead of multiple items. Future studies should consider measuring these constructs standardized assessment instruments such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1984), which has been found to have strong psychometric properties among adolescents (Osman et al., 2008; Rausch et al., 2017). Fourth, data on depression was obtained by self-report and may be subject to social desirability bias. Additionally, EVPs use was measured using a single item. Therefore, product characteristics such as brand type, nicotine content, flavors, and the presence of other substances such as cannabinoids could not be assessed. Therefore, whether a specific type of EVPs is associated with more adverse mental health outcomes could not be ascertained. Lastly, we were unable to explore reasons for use of EVPs among adolescents in the study. Thus, future studies should examine reasons for use of EVPs among adolescents with adverse mental health and consider including theoretically important risk factors to better understand the exact association between EVPs use and mental health among adolescents.

4.3. Conclusion

This study expands the literature on adolescent use of EVPs and suggests that although EVPs use may influence adverse mental health outcomes, its use among adolescent females is associated with a more severe risk profile for mental health outcomes. Therefore, we report that use of EVPs may predispose adolescents to depression and suicidal behaviors. Given the increase in uptake and popularity of EVPs, ease of access and availability, as well as aggressive and targeted advertising and marketing aimed at the adolescent population by vaping manufacturers, policies and prevention efforts are critically needed to curb the rise in adolescent tobacco use trends. School-based prevention initiatives for tobacco use should include screening for mental health conditions as well. In addition, parents, guardians, and school staff should be included in tobacco prevention and cessation efforts.

Highlights.

About one in five adolescents were current users of electronic vaping products (EVPs)

Current and former users of EVPs were more likely to report depression and suicidal behaviors than never users.

Sex moderated the association between EVP use, symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide plan.

Acknowledgements:

This paper is based on public data from the 2017 and 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The study was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant T37MD014218 (PI: Dr. Cavazos-Rehg). The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC, NIMHD, or their partners. Dr. Baiden had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: None to disclose.

References

- Adrian M, Miller AB, McCauley E, & Vander Stoep A (2016). Suicidal ideation in early to middle adolescence: sex-specific trajectories and predictors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(5), 645–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S, Mensah NA, Shan L, & Latham K (2020). Bullying victimization and e-cigarette use among middle and high school students. Journal of School Health, 90(7), 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2008). The education-drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baiden P, LaBrenz CA, Asiedua-Baiden G, & Muehlenkamp JJ (2020). Examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents: Findings from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 125, 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiden P, Stewart SL, & Fallon B (2017). The mediating effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between bullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Findings from community and inpatient mental health settings in Ontario, Canada. Psychiatry Research, 255, 238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiden P, & Tadeo SK (2020). Investigating the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents: Evidence from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 102, 104417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera FC, Loukas A, Li X, Wilkinson AV, & Perry CL (2017). Depressive symptoms predict current e-cigarette use among college students in Texas. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(9), 1102–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannink R, Broeren S, van de Looij–Jansen PM, de Waart FG, & Raat H (2014). Cyber and traditional bullying victimization as a risk factor for mental health problems and suicidal ideation in adolescents. PloS One, 9(4), e94026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Steer RA (1984). Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(6), 1365–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TD, Arnold MK, Ro V, Martin L, & Rice TR (2021). Systematic review of electronic cigarette use (vaping) and mental health comorbidity among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 23(3), 415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalerao A, Sivandzade F, Archie SR, & Cucullo L (2019). Public health policies on e-cigarettes. Current Cardiology Reports, 21(10), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeninger DK, Masyn KE, Feldman BJ, & Conger RD (2010). Sex differences in developmental trends of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts among European American adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(5), 451–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J, Cox B, Clara I, & Sareen J (2006). Use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(11), 818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;48(7):606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, Veliz P, Evans-Polce RJ, Eisman AB, & McCabe SE (2020). Why Are National Estimates So Different? A Comparison of Youth E-Cigarette Use and Cigarette Smoking in the MTF and PATH Surveys. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81(4), 497–504. 10.15288/jsad.2020.81.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kinchen S, Eaton DK, Hawkins J, & Flint KH (2013). Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system—2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports, 62(1), 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, & Brent DA (2006). Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3–4), 372–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch K, Fu M, Ballbè M, Matilla-Santader N, Lidón-Moyano C, Martin-Sanchez JC, … & Martínez-Sánchez JM (2018). Motivation and main flavour of use, use with nicotine and dual use of electronic cigarettes in Barcelona, Spain: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 8(3), e018329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, Hu Y-H, Wong S-W, & Lin H-C (2020). Internalizing and Externalizing Problems as Risk Factors for Initiation and Progression of E-cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use in the US Youth Population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC’s web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Chadi N, Li G, Cerda N, & Weitzman ER (2019). Depressive symptoms and suicidality in adolescents using e-cigarettes and marijuana: A secondary data analysis from the youth risk behavior survey. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 13(5), 362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Sankey JC, Unger JB, Bansal-Travers M, Niederdeppe J, Bernat E, & Choi K (2019). E-cigarette marketing exposure and subsequent experimentation among youth and young adults. Pediatrics, 144(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Yu M, Kim J, & Kim A (2020). E-Cigarette, Cigarette, and Dual Use in Korean Adolescents: A Test of Problem Behavior Theory. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 52(1), 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobley JN, Fiorello ML, & Bailey DM (2018). 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biology, 15, 490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci E, Martin G, 2007. Ethnocultural aspects of suicide in young people: a systematic literature review part 2: Risk factors, precipitating agents, and attitudes toward suicide. Suicide Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(2), 222–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, & Hao J (2017). Electronic cigarette and marijuana use among youth in the United States. Addictive Behaviors, 66, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasagi M, Mantey DS, Harrell MB, & Wilkinson AV (2021). Self-reported history of intensity of smoking is associated with risk factors for suicide among high school students. Plos One, 16(5), e0251099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins L, Turner J, Roberts A, & Soar K (2013). ‘Vaping’ profiles and preferences: an online survey of electronic cigarette users. Addiction, 108(6), 1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxbeck CR (2020). Up in smoke: exploring the relationship between bullying victimization and e-cigarette use in sexual minority youths. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(13), 2221–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxbeck CR, Jaeger JA, & Bleasedale JM (2021). Understanding pathways to e-cigarette use across sexual identity: A multi-group structural equation model. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberlein CK, Frieling H, Köhnlein T, Hillemacher T, & Bleich S (2014). Suicide attempt by poisoning using nicotine liquid for use in electronic cigarettes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(8), 891–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Keator DB, Mbogori J, Taylor D, & Potkin SG (2005). Gender: A major determinant of brain response to nicotine. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 8(1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanshawe TR, Halliwell W, Lindson N, Aveyard P, Livingstone-Banks J, & Hartmann-Boyce J (2017). Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felez-Nobrega M, Haro JM, Vancampfort D, & Koyanagi A (2020). Sex difference in the association between physical activity and suicide attempts among adolescents from 48 countries: A global perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 266, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Scott-Sheldon LA, Olofsson H, Nelson KM, & Japuntich SJ (2021). Electronic Cigarette Cessation among Adolescents and Young Adults. Substance Use & Misuse, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gart R, & Kelly S (2015). How illegal drug use, alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms affect adolescent suicidal ideation: A secondary analysis of the 2011 youth risk behavior survey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(8), 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger AW, & Davis L (2019). A growing number of American teenagers–particularly girls–are facing depression. Pew Research Center, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Willis G, Jamal A, & King BA (2019). Vital Signs: Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2011-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(6), 157–164. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DR, Wang X, Wypij D, Speizer FE, Ware JH, & Dockery DW (1996). Effects of cigarette smoking on lung function in adolescent boys and girls. New England Journal of Medicine, 335(13), 931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, Ingram KM, Mintz S, Hartley C, Valido A, Espelage DL, & Wyman P (2019). Predictors of suicidal ideation and attempts among LGBTQ adolescents: The roles of help-seeking beliefs, peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and drug use. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2443–2455. [Google Scholar]

- Hirdes JP, van Everdingen C, Ferris J, Franco-Martin M, Fries BE, Heikkilä J, Hirdes A, Hoffman R, James ML, & Martin L (2020). The interRAI suite of mental health assessment instruments: An integrated system for the continuum of care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmen TL, Barrett-Connor E, Clausen J, Langhammer A, Holmen J, & Bjermer L (2002). Gender differences in the impact of adolescent smoking on lung function and respiratory symptoms. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, Norway, 1995–1997. Respiratory Medicine, 96(10), 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, & Kaindl AM (2011). Neuronal death and oxidative stress in the developing brain. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 14(8), 1535–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N, Lowry R, & Brown M (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SE, Brown J, Aveyard P, Dobbie F, Uny I, West R, & Bauld L (2019). Vaping for weight control: A cross-sectional population study in England. Addictive Behaviors, 95, 211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob L, Smith L, Jackson SE, Haro JM, Shin JI, & Koyanagi A (2020). Secondhand smoking and depressive symptoms among in-school adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(5), 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalkanen V, Värelä V, & Kalliomäki J (2016). Case report: Two severe cases of suicide attempts using nicotine containing e-cigarette liquid. Duodecim; Laaketieteellinen Aikakauskirja, 132(16), 1480–1483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaid A (2018). Male rape, masculinities, and sexualities. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 52, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn GD, & Wilcox HC (2020). Marijuana use is associated with suicidal ideation and behavior among US adolescents at rates similar to tobacco and alcohol. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, & Thornton J (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4(5), 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, & Kim K (2021). Electronic cigarette use and suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Public Health, 43(2), 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SM, Jung J-W, Park I-W, Ahn CM, Kim Y-I, Yoo K-H, Chun EM, Jung JY, Park YS, & Park J-H (2016). Gender differences in relations of smoking status, depression, and suicidality in Korea: Findings from the Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey 2008-2012. Psychiatry Investigation, 13(2), 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, & Lattanner MR (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Johnson SE, Mitrou F, Lawn S, & Sawyer M (2021). Tobacco smoking and mental disorders in Australian adolescents. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 00048674211009617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner WV, Janssen T, Kahler CW, Audrain-McGovern J, & Leventhal AM (2017). Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 96, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Ahn IY, Park CS, Kim BJ, Lee CS, Cha B, … & Choi JW (2020). Early menarche as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in girls: the Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. Psychiatry Research, 285, 112706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, & Lee K-S (2019). Association of depression and suicidality with electronic and conventional cigarette use in South Korean adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(6), 934–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner CA, Sundar IK, Yao H, Gerloff J, Ossip DJ, McIntosh S, Robinson R, & Rahman I (2015). Vapors produced by electronic cigarettes and e-juices with flavorings induce toxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response in lung epithelial cells and in mouse lung. PloS One, 10(2), e0116732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Sussman S, Kirkpatrick MG, Unger JB, Barrington-Trimis JL, & Audrain-McGovern J (2016). Psychiatric comorbidity in adolescent electronic and conventional cigarette use. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 73, 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Oshri A, Baezconde-Garbanati L, & Soto D (2016). Profiles of bullying victimization, discrimination, social support, and school safety: Links with Latino/a youth acculturation, gender, depressive symptoms, and cigarette use. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maessen GC, Wijnhoven AM, Neijzen RL, Paulus MC, van Heel DA, Bomers BH, Boersma LE, Konya B, & van der Heyden MA (2020). Nicotine intoxication by e-cigarette liquids: A study of case reports and pathophysiology. Clinical Toxicology, 58(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R (2015). Association between peer victimization in adolescence and cannabis use: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R (2017). Bullying and other forms of peer victimization in adolescence and alcohol use. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 18(4), 457–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez LS, Hughes S, Walsh-Buhi ER, & Tsou M-H (2018). “Okay, we get it. You vape”: An analysis of geocoded content, context, and sentiment regarding e-cigarettes on Twitter. Journal of Health Communication, 23(6), 550–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, Cebria A, Gabilondo A, & Gili M (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 265–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SM, Seegan PL, Roush JF, Brown SL, Sustaíta MA, & Cukrowicz KC (2016). Retrospective cyberbullying and suicide ideation: The mediating roles of depressive symptoms, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(16), 2602–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, & Runions KC (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, & Han B (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, & Wedel AV (2017). Vaping to lose weight: Predictors of adult e-cigarette use for weight loss or control. Addictive Behaviors, 66, 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, Puckett JA, 2016. The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Glynn TJ, & Abrams DB (2014). Youth experimentation with e-cigarettes: Another interpretation of the data. Jama, 312(6), 641–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, De Girolamo G, & Gluzman S (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ, Phillips LD, Balfour D, Curran HV, Dockrell M, Foulds J, Fagerstrom K, Letlape K, Polosa R, & Ramsey J (2016). E-cigarettes are less harmful than smoking. The Lancet, 387(10024), 1160–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Williams JE, & Bailey J (2008). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in nonclinical adolescent samples. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(1), 83–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, & Min Y-G (2018). The emerging method of suicide by electronic cigarette liquid: A case report. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 33(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro B, Correa JB, Simmons VN, Harrell PT, Menzie NS, Unrod M, … & Brandon TH (2016). Gender differences in use and expectancies of e-cigarettes: online survey results. Addictive Behaviors, 52, 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit A, Buchwald J, Latvala A, Heikkilä K, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, & Korhonen T (2019). Predictive association of smoking with depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of adolescent twins. Prevention Science, 20(7), 1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit A, Korhonen T, Buchwald J, Heikkilä K, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Rose RJ, Kaprio J, & Latvala A (2019). Testing the reciprocal association between smoking and depressive symptoms from adolescence to adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch E, Racz SJ, Augenstein TM, Keeley L, Lipton MF, Szollos S, … & De Los Reyes A (2017). A multi-informant approach to measuring depressive symptoms in clinical assessments of adolescent social anxiety using the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Convergent, incremental, and criterion-related validity. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46(5), 661–683. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, He J-P, Curry L, & Merikangas K (2012). Cigarette smoking and mood disorders in US adolescents: Sex-specific associations with symptoms, diagnoses, impairment and health services use. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(4), 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehm KE, Rojo-Wissar DM, Feder KA, Mojtabai R, Spira AP, Thrul J, & Crum RM (2019). E-cigarette use and sleep-related complaints among youth. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E, Fraser A, Gunnell D, Joinson C, & Mars B (2020). Timing of menarche and self-harm in adolescence and adulthood: a population-based cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 50(12), 2010–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IR, Lilly CL, Jia H, Larkin GL, Miller TR, Nelson LS, Nolte KB, Putnam SL, Smith GS, & Caine ED (2016). Self-injury mortality in the United States in the early 21st century: A comparison with proximally ranked diseases. Jama Psychiatry, 73(10), 1072–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodelli M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Dumon E, Portzky G, & DeSmet A (2018). Which healthy lifestyle factors are associated with a lower risk of suicidal ideation among adolescents faced with cyberbullying? Preventive Medicine, 113, 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkiewicz JA, Zhang Z, Gonçalves FM, Tizabi Y, Zelikoff JT, & Aschner M (2020). Neurotoxicity of e-cigarettes. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 138, 111245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddleson ML, Kozlowski LT, Giovino GA, Homish GG, Mahoney MC, & Goniewicz ML (2016). Assessing 30-day quantity-frequency of US adolescent cigarette smoking as a predictor of adult smoking 14 years later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen Choudhury R (2021). Vaping Regulations and Mental Health of High School Students. Available at SSRN; 3773745. [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Homa DM, & King BA (2016). Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(14), 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SL, Baiden P, & den Dunnen W (2013). Prescription medication misuse among adolescents with severe mental health problems in Ontario, Canada. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(5), 404–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B (2021). Gender Difference in the Association Between E-Cigarette Use and Depression among US Adults. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 12(1), 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Graham DP, Wilkinson AV, & Kosten TR (2021). Nicotine inhalation and suicide: Clinical correlates and behavioral mechanisms. The American Journal on Addictions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Carr T, Oke O, Jaunky T, Breheny D, Lowe F, & Gaça M (2016). E-cigarette aerosols induce lower oxidative stress in vitro when compared to tobacco smoke. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 26(6), 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AB, Tebes JK, & McKee SA (2015). Gender differences in age of smoking initiation and its association with health. Addiction Research & Theory, 23(5), 413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kingree JB, & Lamis D (2019). Associations of adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behaviors in adulthood in a US nationally representative sample. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(1), 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobore TO (2019). On the potential harmful effects of E-Cigarettes (EC) on the developing brain: The relationship between vaping-induced oxidative stress and adolescent/young adults social maladjustment. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokle R, & Pedersen W (2019). “Cloud chasers” and “substitutes”: E-cigarettes, vaping subcultures and vaper identities. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(5), 917–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, Sharapova SR, Johnson SE, Kennedy SM, & Caraballo RS (2018). Reasons for electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(6), 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Bowes L, Farrington DP, & Lösel F (2014). Protective factors interrupting the continuity from school bullying to later internalizing and externalizing problems: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of School Violence, 13(1), 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JM, Brener N, Thornton J, Harris WA, Bryan LN, Shanklin SL, Deputy N, Roberts AM, Queen B, & Chyen D (2020). Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, et al. , 2017. Mental health disparities among Canadian transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Glasser AM, Johnson AL, Collins LK, Niaura RS, & Abrams DB (2017). Frequency of youth e-cigarette and tobacco use patterns in the United States: measurement precision is critical to inform public health. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(11), 1345–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, & Vandenbroucke JP (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(8), 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DN, & Fan W (2018). Ethnic and sex differences in E-cigarette use and relation to alcohol use in California adolescents: the California Health Interview Survey. Public Health, 157, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yimsaard P, McNeill A, Yong HH, Cummings KM, Chung-Hall J, Hawkins SS, … & Hitchman SC (2021). Gender differences in reasons for using electronic cigarettes and product characteristics: Findings from the 2018 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 23(4), 678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zych I, Farrington DP, & Ttofi MM (2019). Protective factors against bullying and cyberbullying: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 4–19. [Google Scholar]