Abstract

The extant literature on suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (STB) has highlighted increased patterns of risk among specific minoritized populations, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, intersex, two spirit, and queer (LGBTQ+) youth. Compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers, LGBTQ+ youth are at increased risk for having STB. Identity-specific stressors such as homonegativity and anti-queerness are among the unique factors posited to contribute to this risk and inhibit factors that protect against suicide. The school setting has been a focal point for suicide prevention and intervention and may also play a key role in linking students to care; however, schools also hold the potential to provide supports and experiences that may buffer against risk factors for STB in LGBTQ+ students. This systematic literature review presents findings from 44 studies examining school-related correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ students, informing an ecological approach to suicide prevention for school settings. Findings underscore the importance of school context for preventing STB in LGBTQ+ youth. Approaches that prioritize safety and acceptance of LGBTQ+ youth should span multiple layers of a student’s ecology, including district and state level policies and school programs and interventions, such as Gender and Sexuality Alliances and universal bullying prevention programs. Beyond their role as a primary access point for behavioral health services, schools offer a unique opportunity to support suicide prevention by combating minority stressors through promoting positive social relationships and a safe community for LGBTQ+ students.

Keywords: LGBTQ+, Sexual Gender Minoritized, Gender Diverse, Suicide, Schools, Sexual Orientation

Introduction

Over the past decade there has been a significant increase in adolescent deaths by suicide and hospitalizations for suicide-related thoughts and behaviors (STB; e.g., ideation, attempts, intentional self-harm with the intention to die; Plemmons et al., 2018). As compared to adolescents who identify as heterosexual and/or cisgender, sexual and gender minoritized youth identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, questioning, intersex, two spirit, and queer (LGBTQ+) appear to be at greater risk of STB (Di Giacomo et al., 2018; Johns et al., 2020), with LGBTQ+ students comprising 16%–24% of deaths by suicide (Ream, 2019). LTBTQ+ youth are at significantly higher risk of making a suicide attempt, with 23% of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth reporting having made a suicide attempt in the past year as compared to 5.4% of heterosexual youth (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). The risk may be even greater for transgender youth, with self-report estimates suggesting that 40% of transgender individuals made a suicide attempt within their lifetime and 73% reported their first attempt before the age of 18 years (James et al., 2016).

Although it is well established that multiple factors contribute to risk for suicide among youth, LGBTQ+ youth commonly encounter unique stressors related to their sexual orientation or gender identity, including homonegativity and anti-queerness. These biases may manifest as rejection by parents, peers, and teachers, and experiences of sexual prejudice in their communities and schools, which in turn may exacerbate risk for STB (Hong et al., 2011). Schools influence STB through quality of in-school relationships, implicit messaging about the acceptability or unacceptability of sexuality and gender diversity, and access to comprehensive suicide prevention programs and evidence-based interventions (Espelage et al., 2019; Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage, 2019; Hong et al., 2011). Schools may promote a sense of safety and acceptance by way of inclusive policies and positive adult relationships (Kosciw et al., 2018); however, they can also harbor stressors for suicide-related risk, such as discriminatory policies and anti-LGBTQ+ bullying, harassment, aggression, and violence (Kosciw et al., 2018). These experiences permeate social interactions, relationships, feelings of safety, values, and beliefs (Hong et al., 2011) that comprise adolescent perceptions of school climate (Rudasill et al., 2018) and can extend into social media and the community.

Despite the critical role schools can play in mitigating suicide risk for LGBTQ+ youth (di Giacomo et al., 2018) and for all youth (Singer et al., 2019), findings regarding the role of schools in preventing suicide among LGBTQ+ students have yet to be systematically integrated. Although previous reviews have explored suicide-related risk and protective factors in LGBTQ+ youth more broadly (e.g., Gorse, 2020; Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage 2019), no reviews have taken a strengths-based approach to understanding school-related correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ youth. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesize research on school-related correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ youth. Using an ecologically informed, strengths-based approach, we also aimed to develop a school-based suicide prevention model for LGBTQ+ students based on these findings.

LGBTQ+ Youth and Risk for STB

The term LGBTQ+ encompasses a diverse population of youth, including, but not limited to, individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (indicating sexual identity) and individuals identifying as transgender and nonbinary (indicating gender identity). The terms questioning and queer are often used as umbrella terms to refer to non-cisgender and non-heterosexual identities. Questioning is typically used to describe those questioning their sexual orientation and/or gender identity and queer (or two-spirited in First Nation, Aboriginal, Native American, Alaskan Native, and Indigenous individuals) can reflect a spectrum of identities and orientations that counter mainstream and colonial constructions of gender and sexual orientation (The Trevor Project, n.d.). Within and across LGBTQ+ identities, individuals may experience environments differently (from one another and from heterosexual and cisgender peers).

LGBTQ+ youth share the common experience of navigating heteronormative environments, or environments that normalize and privilege heterosexuality (Herz & Johansson, 2015), as sexual and gender minoritized youth. Collectively, they exhibit increased risk of STB, as compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers. In a global sample of 2.5 million sexual and gender minoritized youth, those who identified as gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth were approximately four times as likely to attempt suicide as compared to their cisgender, heterosexual peers, and transgender youth were nearly 6 times as likely to do so (di Giacomo et al., 2018). Although confidence intervals around these odds ratios are somewhat wide (suggesting substantial heterogeneity among intragroup experiences; di Giacomo et al., 2018), the extant literature consistently indicates that LGBTQ+ youth experience suicidal thoughts, make plans, and attempt suicide at higher rates than their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Marshal et al., 2011; Saewyc et al., 2007).

In a meta-analysis of 44 LGBTQ+-only samples, Hatchel, Polanin, and Espelage (2019) found that gender non-conformity was the strongest identity correlate of STB. Indeed, the Trevor Project (2020a) estimated that 21% of trans and non-binary youth had attempted suicide and 52% had considered it. Limited by few studies disaggregating risk for transgender youth specifically, Di Giacomo and colleagues (2018) also found that transgender youth may face the highest risk among LGBTQ+ youth for suicide attempts when compared to heterosexual youth. In contrast, rates do not appear to vary widely among lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) students (Di Giacomo et al., 2018; Saewyc et al., 2007). Prevalence rates of suicidal ideation in the United States (U.S.) and Canada have ranged from 20%–72% in bisexual students, 26%–71% in gay or lesbian students, and 11%–35% in mostly heterosexual students; for suicide attempts they have ranged from 12%–47% in bisexual students, 9%–44% in gay or lesbian students, and 7%–23% in mostly heterosexual students (Saewyc et al., 2007).

Prevalence of STB may also differ across racial and ethnic backgrounds. As suicide rates among Black and Indigenous youth rise in the U.S., they also increase for Black and Native American/Alaskan Native queer and two-spirit youth (and other LGBTQ+ youth of color) at alarming rates (Lindsey et al., 2019; Pritchard, 2013). According to recent data, about 35% of Black queer or LGBTQ+ youth have seriously considered ending their lives and approximately 19% have attempted suicide (The Trevor Project, 2019a, 2020b). Likewise, about 33% of Native American or Alaskan Native LGBTQ+ youth reported a past-year suicide attempt (The Trevor Project, 2020c). The same researchers found that, among other queer racial and ethnic identity groups, about 17% of Latinx, 15% of Asian or Pacific Islander, and 18% of White non-Latinx youth reported a past-year suicide attempt (The Trevor Project, 2019b).

Intersectionality and STB

Variability in prevalence of STB among LGBTQ+ youth by sexual, gender, racial, and ethnic identities indicate the need to apply an intersectional lens. Intersectionality acknowledges the ways in which interlocking systems of privilege, power, and oppression produce different experiences for individuals based on their combination of identities (Crenshaw, 1989). In other words, a person’s LGBTQ+ identity is inseparable from their other identities in shaping an individual’s social experiences and worldview.

Students who represent various minoritized identities are impacted by multiple forces of discrimination and oppression that create challenges that are unique to the individual (Films Media Group, 2016). For example, Black students may face racism and race-based discrimination in addition to homonegativity and anti-queerness in schools, whereas white students may only face the latter type of discrimination. Likewise, the stressors associated with identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual may be compounded for students also identifying as transgender (Le Salle et al., 2019). Thus, data on youth risk for contemplating and attempting suicide must be considered in the context of their intersecting sexual, gender, racial, ethnic, cultural, and other identities.

Previous work also suggests that although risk for STB appears to be higher among LGBTQ+ youth than heterosexual youth overall (Saewyc et al., 2007), these discrepancies in risk may vary for particular racial and ethnic groups. For example, among American Indian youth, rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts appear to be consistent across sexual and gender identities, perhaps because risk is higher for American Indian youth overall (Saewyc et al., 2007). In Black youth, however, preliminary findings suggest higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide plans in LGB youth as compared to heterosexual youth (Mereish et al., 2019). Findings from an adult sample of LGB individuals reporting on suicide attempts before the age of 24 years also support a link between being Black or Latinx and reporting a suicide attempt that is not explained by youth onset depression or substance use (O’Donnell et al., 2011). In other words, irrespective of mental health functioning during childhood and adolescence, racism (and other racial and ethnic minoritization experiences) may confer risk for STB in LGBTQ+ individuals.

Importantly, youth of all orientations and identities contemplate suicide with varying levels of intention and risk of attempt and injury (Ribiero et al., 2016; Silverman & Berman, 2014). Moreover, LGBTQ+ youth may engage in self-injurious behavior for reasons other than attempting to end one’s life (e.g., self-soothing or gaining attention from others; Carr, 1977; Iwata et al., 1994; Liu et al., 2019), resulting in their overrepresentation among youth requiring treatment for non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors and STB (Berona et al., 2020). Thus, the prevalence of STB, likely compounded by engagement in non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors, as well as the heterogeneity of risk factors for suicide, signify the urgency for identifying and intervening in suicide risk in LGBTQ+ youth.

School-Related Risk and Protective Factors for STB in LGBTQ+ Youth

Schools are often called on to provide suicide prevention supports and services (e.g., Singer et al., 2019) and have a legal and ethical duty to do so (more than half of the states in the U.S. are required to provide suicide prevention training to school staff; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2020). In practice, schools are a primary mechanism for delivering emotional and behavioral interventions to adolescents with psychiatric disorders (e.g., Costello et al., 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Yet, frameworks for approaching suicide prevention in schools have largely focused on tiered approaches to interventions without identifying specific recommendations for supporting LGBTQ+ students in schools (e.g., Singer et al., 2019; Miller & Mazza, 2018).

In general, both research and media have focused more narrowly on the link between bullying and increased risk for STB in LGBTQ+ youth (Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, 2020). Although empirical work consistently supports a strong correlation between bullying and STB in LGBTQ+ youth (Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage, 2019), this emphasis can overlook the significant toll of systemic marginalization on LGBTQ+ youth and obscure the need for critical policy change (Payne & Smith, 2013). Instead, multiple interpersonal and ecological factors should be considered in identifying pathways that confer risk for suicide (Silverman & Berman, 2014).

School climate and related constructs, such as feelings of safety and support in the school ecosystem, have been identified as important considerations for preventing suicide in LGBTQ+ youth (Espelage, Merrin, & Hatchel, 2018; Kosciw et al., 2018). Schools can be considered a place where youth connect with supportive adults, find excitement and self-confidence in academic achievement, and develop peer communities, all of which may provide a safe and affirming environment and protect against STB (Bilsen, 2018; Kidd et al., 2006; Whitlock et al., 2014). A robust literature supports the association between school connectedness or feelings of belonging (i.e., the extent to which students feel accepted, included, and close to other members of the school community; Goodenow, 1993) and healthier mental and behavioral outcomes, including lower risk for STB (King et al., 2019; Marraccini & Brier, 2017).

Unfortunately, LGBTQ+ youth appear less likely to feel connected to school as compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Joyce, 2015). As noted by Hong and colleagues (2011), there is extensive research indicating that LGBTQ+ youth may perceive their school’s climate as less warm, supportive, and caring as compared to other students (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2018; White et al., 2018), with these negative experiences intensifying for students identifying as both gender minoritized and sexual minoritized (La Salle et al., 2019). This compounding effect likely extends to ethnic and racial minoritized students as well, with the intersection of oppression and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity potentially further exacerbating negative school experiences (La Salle et al., 2019).

Inclusive school-based sexuality education can have a positive impact on the mental health of LGBTQ+ youth (Naser et al., 2020; Proulux et al., 2019); however, teachers receive little guidance on how to deliver inclusive sexuality education (Schneider & Hirsch, 2020). In fact, in several states, laws and school standards actively prohibit curricula from including sexual and gender diverse identities (Elia & Eliason, 2010). A lack of training and support may leave teachers at a loss for how best to support their LGBTQ+ students and in turn may erect barriers between them and their students (Meyer, 2008).

Feeling unsupported by teachers (Diaz et al., 2010) and experiencing bullying and other problems with peer relationships (Gower, Rider, McMorris, & Eisenberg, 2018) can exacerbate fear of being at school and ultimately prevent incident reporting that could link students to care (Russell et al., 2016). Peer bullying and harassment related to school-based sexual prejudice have also been consistently identified as contributors to risk for several negative health outcomes, including STB (e.g., Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Friedman et al., 2006; Gower, Rider, McMorris, & Eisenberg, 2018; Moyano et al., 2020). Fortunately, positive social interactions with others in the school community (e.g., peer and teacher-led interventions and support) may buffer against the negative effects of attending a school that might otherwise feel hostile (De Pedro et al., 2018; Wernick et al., 2014).

One way that schools attempt to affirm and develop LGBTQ+ identities and foster community is through the formation of Gender and Sexuality Alliances ([GSAs] formerly known as Gay-Straight Alliances; Poteat et al., 2020). GSAs can help foster a sense of collective civic engagement and advocacy (Poteat et al., 2018), building on the many strengths inherent to the LGBTQ+ community who have consistently advocated for and actualized safer and improved environments for LGBTQ+ youth (Diemer et al., 2020). The presence of a GSA at school has been found to mitigate victimization of LGBTQ+ youth (Marx & Kettrey, 2016) and when schools include LGBTQ+-focused curricula and have a GSA, they are perceived to be safer for queer youth (Toomey et al., 2012; Poteat et al., 2015). In these contexts, schools have the potential to provide caring and supportive relationships for youth, thereby facilitating positive identity development to reinforce the many cultural and community strengths of LGBTQ+ youth and potentially buffer against risk for STB.

Theoretical Understanding of Suicide Risk

Several theories have been proposed to guide understanding of suicide risk, with contemporary theories applying an “ideation-to-action” framework. These theories prioritize understanding of the processes by which an individual moves from the development of suicidal ideation to making a suicide attempt, positing that the development of capability for making a suicide attempt may help explain this transition (Klonsky & May, 2015; Van Orden et al., 2010). The capability to make a suicide attempt may be strengthened through dispositional factors such as elevated pain tolerance and diminished fear by way of behavioral experiences such as self-injury and other forms of violence and pain that may desensitize the fear response to pain and death, which can otherwise serve as a protective mechanism against self-harm (Klonsky et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2010).

Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, a commonly studied ideation-to-action framework, posits that ideation results from feeling hopeless about both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, with higher capabilities for suicide leading to an attempt (Van Orden et al., 2010). Other ideation-to-action frameworks (e.g., integrated motivational-volitional model [IMV], O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018; the three-step theory of suicide, Klonsky & May, 2015) postulate similar factors that may differentiate ideation and attempts, with convergence around the importance of psychological pain, hopelessness, and feelings of disconnect for understanding suicidal ideation. IMV identifies feelings of defeat and entrapment as leading to ideation and volitional motivators (e.g., access to lethal means, exposure to suicidal behavior, planning, and impulsivity) as leading to attempt (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Klonsky and May (2015) proposed the three-step theory of suicide in which pain (i.e., emotional and psychological), hopelessness, connectedness, and suicide capacity are considered the primary factors underlying ideation and attempts. Specifically, a combination of pain and hopelessness are posited to lead to suicidal ideation, which is intensified or mitigated in accordance with levels of connectedness.

Researchers have called for improved understanding of ideation-to-action frameworks addressing suicide risk in LGBTQ+ individuals (Hatchel, Ingram, et al., 2019; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2018). A recent review guided by an ideation-to-action framework to understand suicide risk in transgender individuals highlighted the need to attend to sources of psychological pain, social connectedness, and capability for suicide, as well as intersections with other cultural factors such as race and ethnicity (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2018). Psychological or emotional pain can stem from any combination of experiences including physical suffering, social isolation, feelings of disconnect, negative self-perceptions, and defeat and entrapment (Klonsky & May, 2015). Yet, LGBTQ+ youth face additional stressors unique to systemic biases (e.g., homonegativity, binegativity, transnegativity) that invalidate, discriminate against, and harm people with LGBTQ+ identities, which may also contribute to feelings of hopelessness and disconnect.

According to the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003), both proximal and distal risk factors specific to minoritized sexual and gender identities can exacerbate psychological distress in LGBTQ+ youth. These may include experienced and perceived prejudice (victimization, violence, heterosexism), expectations of prejudice, identity concealment, and internalized sexual prejudice (Meyer, 2003). Findings from numerous studies provide evidence for the detrimental effects of these experiences on mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), self-harm, and suicide ideations and attempts (Burns et al., 2014; Chodzen et al., 2019; Fulginiti et al., 2020; Lucassen et al., 2017).

When situated within an ideation-to-action framework, minority stressors may intersect with other types of pain, which in turn can contribute to feelings of disconnect and burdensomeness (Baams et al., 2015; Fulginiti et al., 2020). As a result, youth may experience feelings of hopelessness that ultimately intensify suicidal ideation. Individuals in their communities (schools and others) often fail to meaningfully connect with minoritized students, who face widespread homonegativity and transnegativity (Frohard-Dourlent, 2018; Ullman, 2017). Moreover, the internalization of discriminatory beliefs that prevent individuals from valuing their own identities may contribute to feelings of hopelessness (Chodzen, et al., 2019; Hall, 2018). Taken together, many components of the minority stress model align with risk factors that can lead to or intensify suicidal ideation (Fulginiti et al., 2020). When considering the strong link between the severity of suicidal ideation and future suicide attempts, such risk factors may facilitate the shift from ideation to action (Fulginiti et al., 2020; Horowitz et al., 2015).

Theoretical Framework for Understanding School Context and Suicide Risk

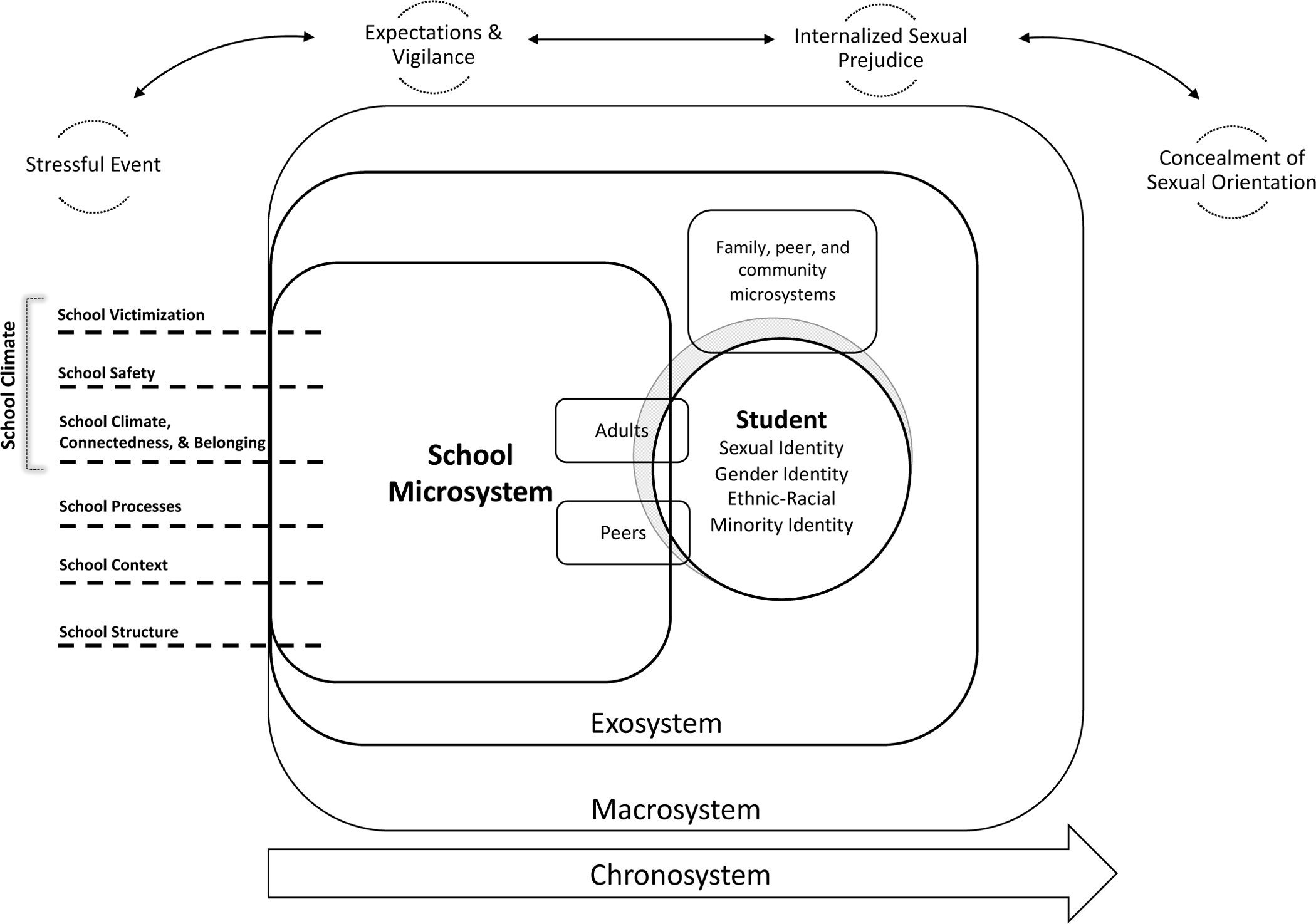

Risk and protective factors associated with pain, hopelessness, connectedness, and suicide capacity should be considered across all aspects of the lives of LGBTQ+ youth. Understanding school-related risk and protective factors for STB is particularly important when considering the significant amount of time youth spend in school or school-related environments (e.g., extra-curricular activities, social media platforms interacting with school peers). Therefore, we frame seminal theories (ideation-to-action and minority stress model) for understanding suicide risk in LGBTQ+ youth within a systems view of school climate (SVSC), which applies an ecological lens to conceptualizing school climate (Rudasill et al., 2018). Although a traditional ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1996) places the adolescent (or youth ontosystem) at the center of multiple systems (i.e., microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem), the SVSC instead positions the school microsystem at the center of the framework. That is, school microsystems can be viewed as interfacing indirectly with students and other microsystems and as situated within a broader ecological framework.

SVSC defines the school microsystem based on four main characteristics: (a) school climate, (b) school structure, (c) school processes, and (d) school context. Within this microsystem, critical aspects of school climate include shared beliefs and values among school members; peer and adult relationships; and perceptions of social, emotional, and physical safety in school. The remaining three components of the school microsystem include the school structure (e.g., school size, availability of courses), processes (e.g., disciplinary hierarchies, decision-making), and context (e.g., student-body characteristics; Rudasill et al., 2018).

In addition to traditional mesosystems, which comprise connections between microsystems (e.g., school, family, peer), Rudasill and colleagues (2018) introduced the concept of nanosystems, which are unique to schools and refer to groups nested within microsystems. Instead of interfacing directly with students, the school microsystem is proposed to connect students by way of these nanosystems, such as classrooms, extracurricular activities, and informal peer groups. As in the traditional ecological framework, school, family, and peer microsystems are situated within more distal systems, including the (a) community exosystem (e.g., indirect contexts such as family workplaces), (b) social and educational macrosystem (e.g., beliefs and practices related to community and culture), and (c) chronosystem (e.g., maturation, change over time).

Purpose of the Current Work

For LGBTQ+ youth, minority stressors are embedded across all aspects of the student’s ecology. Accordingly, risk and protective factors within the school microsystem and across school-family and school-community mesosystems may interact with minority stressors to modulate the intensity of suicidal ideation and influence pathways from ideation to action. This relationship is likely transactional, with LGBTQ+ youth’s perceptions of their school ecology and relationships reciprocally influencing their experiences, expectations, and internalization of prejudice and discrimination. Thus, applying a SVSC lens for understanding how school-related risk and protective factors may influence STB among LGBTQ+ youth may provide important insights for improving school-based suicide prevention efforts prioritizing LGBTQ+ youth.

Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to (a) identify school-related correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ youth and (b) develop a school-based approach to suicide prevention grounded in an ecological and strengths-based framework. Because schools play a significant role in supporting developing youth, a deeper understanding of how the school ecology can better protect against suicide-related risk for LGBTQ+ youth is warranted. In addition to serving as a primary access point for behavioral and mental health services, schools may be able to diminish some of the stressors faced by LGBTQ+ youth by fostering positive social relationships among students and adults and by providing safe communities for LGBTQ+ youth. Although existing reviews and meta-analyses have explored correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ youth more broadly (e.g., Gorse, 2020; Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage, 2019), no reviews have explicitly addressed school-related correlates of STB in LGBTQ+ youth or focused on school ecology for preventing suicide in LGBTQ+ youth taking a strengths-based approach.

Method

We conducted a systematic search and retrieval process following guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009). This review was part of a larger project that identified peer-reviewed, published articles examining school-related constructs (e.g., school bullying, school connectedness, school engagement) and suicide-related outcomes in both LGBTQ+ and ethnic-racial minoritized youth. The review of studies focused on ethnic-racial minoritized youth is presented separately (see Marraccini et al., 2020); thus, for the current study, we present the search and retrieval process for both studies and then focus specifically on findings related to LGBTQ+ youth.

The primary aim of this review was designed to be hypothesis-generating, as opposed to a hypothesis-testing, to better understand a wide range of school-related influences of STB in minoritized student populations to inform practice and future research. We made methodological choices in service of this aim. Conducting a rigorous systematic review and using a salient and supported framework to organize, examine, and interpret findings allowed us to capture a broad view of the published literature, with an emphasis on examining variability in context and methods as well as gaps in primary data. We did not complete a quantitative meta-analysis for two reasons. First, meta-analysis is not well suited to the aims of the current study. Second, our sample of studies is not sufficiently powered. In other words, there is not a justifiable way to group our sample’s studies such that they are sufficiently representative of larger population(s) in large enough numbers to meet assumptions for analyses.

Search and Retrieval Process

Search terms were selected to represent three categories: (a) suicide-related thoughts and behaviors, (b) school, and (c) LGBTQ+ and racial-ethnic minoritized status (specific terms are listed in Supplementary Materials). The comprehensive search was performed once, on August 8, 2019, in PsycINFO, PubMed, Academic Search Premier, ERIC, and Education Full Text. Because the larger review focused on both racial-ethnic minoritized youth and LGBTQ+ youth, we also selected articles from additional reviews focused on ethnic-racial minoritized individuals (presented in Supplementary Materials) and identified one review that focused on Latinx youth identifying as LGBTQ+ (Garcia-Perez, 2020). Accordingly, we also selected studies from the Garcia-Perez (2020) review for the current paper.

Although the search did not include any review of reference sections in selected articles or articles citing identified manuscripts, to assess the appropriateness of the review search terms and databases, we searched for relevant studies within two review studies (presented in the Introduction) that focused on ecological influences of STB in LGBTQ+ youth (Hong et al., 2011) and bullying among LGBTQ+ youth (Gower, Rider, McMorris, & Eisenberg, 2018). We found that all studies meeting eligibility criteria were already identified in the larger search, indicating preliminary support for our data search and retrieval process in capturing relevant review articles focused on school-related experiences in relation to STB in LGBTQ+ youth.

The first, fifth, and seventh authors completed a training in eligibility criteria. Following the training, we examined titles, abstracts, and full texts independently (i.e., the records were split evenly between authors). Studies were selected for this review based on the following eligibility criteria:

The study used a direct assessment of STB such as suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths (indirect measures exclusively focused on depression and anxiety were excluded).

The study examined a school related construct (e.g., school climate, bullying, school relationships) in relation to suicide-related thought or behaviors.

The study presented findings that either (a) were based on a LGBTQ+ K-12 population; or (b) compared differences between LGBTQ+ and majority (i.e., heterosexual/cisgender) students in a K-12 population.

The study was published between 1999 and 2019. This time period was selected because of the increase in scholarship focused on the topic of LGBTQ+ youth in schools over this period (Graves, 2015; Heck et al., 2016), with longitudinal datasets such as the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS) beginning to devote questions ascertaining sexual identity and sex of sexual contacts during the mid-1990s (CDC, 2017).

The study was peer-reviewed and published in English. Given the wide scope of the review, in that it aimed to understand a broad range of school-related influences of STB, studies that were not published in peer-reviewed journals (e.g., dissertations, unpublished datasets) were excluded.

The study was conducted in the US. Because there are distinct sociopolitical and sociocultural considerations in the treatment of and acceptance towards LGBTQ+ individuals and policy influencing school practices that vary across the globe (Poushter & Kent, 2020), studies conducted in countries outside of the US were excluded.

Data Extraction and Coding

Data were extracted into a predetermined, standardized coding manual that identified the sampling method, study population, sample size, location, demographic characteristics, school construct and measure, suicide construct and measure, and key findings. Although quality of studies was not coded during data extraction, we identified the larger study or sampling method to ascertain study rigor. The majority of findings (37 studies out of 46 studies) were based on standardized, national, or statewide studies such as the YRBS and the Dane County Youth Assessment study.

Findings were organized based on the school constructs they explored, which were in turn categorized according to components of the school microsystem identified within the SVSC (climate, structures, processes, and context; see Supplementary Materials for coding structure). The SVSC was selected to guide the coding structure of study findings because it provides a multisystems view of school climate and other school-related factors and provides guidance for specifying levels of these factors for research and analysis. The first and fifth author independently coded each of the study findings based on the definitions provided by Rudasill (2018; see Supplementary Materials). In the case of discrepancies, authors met to come to consensus. Interrater agreement was adequate (percent agreement was 87%).

The second author checked final study information and key findings for accuracy, which are presented in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1. When available, effect sizes are presented along with key findings, with interpretations based on broad recommendations (i.e., small odds ratio [OR] = 1.52, medium OR = 2.74, or large OR = 4.72; Chen et al., 2010) and consideration of indicators of precision and variability (e.g., confidence intervals; Durlak, 2009). Both LGBTQ+ identity (e.g., sexual minoritized1 youth, LGB) and type of STB (e.g., suicidal ideation, suicide attempts) are presented in accordance with descriptions provided by individual studies, with STB indicating a combined measure of multiple suicide-related thoughts or behaviors.

Table 1.

Included Studies Exploring School-related Factors and Suicide in LGBTQ+ Youth

| Study | Sample size | Sample | Dataset/Sampling Method | School level or age | Geographical location | School construct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annor et al. (2018) | 6790 | Sexual orientation discordance, or sexual contact inconsistent with identity | 2015 National YRBS | High | US | Victimization |

| Ballard et al. (2017) | 1550 | LGBQ | YRBS | High | Rural Appalachia in Western NC | Victimization |

| Barnett et al. (2019) | 10,593 | Gay, lesbian, bisexual, not sure | 2012 DC YRBS | NR | District of Columbia | Victimization; Safety |

| Birkett et al. (2009) | 7376 | LGB | 2004 Dane County Youth Assessment | Middle | Dance County, WI | Climate |

| Bontempo & D’Augelli (2002) | 315 | LGB | 1995 Massachusetts and Vermont YRBS | High | VT and MA | Victimization |

| Bouris et al. (2016) | 1907 | Sexual minoritized | 2011 Chicago YRBS | High | Chicago, IL | Victimization; Safety |

| Button (2015) | 2639 | LGBQ | 2007 Delaware YRBS | High | DE | Victimization; Connectedness |

| Button & Worthen (2014) | 539 | LGBQ and youth involved in same-sex behavior | 2003, 2005, 2007 Delaware YRBS | High | DE | Victimization |

| Colvin et al. (2019) | 240 | Sexual/gender minoritized | Randomized control trial of a game-based intervention for sexual/gender minoritized youth using social media recruitment methods | High | US | Climate; Connectedness; Processes |

| Coulter et al. (2017) | 24,459 | LGBQ | 2012 MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey | High | Boston, MA | Connectedness |

| DeCamp & Bakken (2016) | 7326 | Sexual minoritized | 2006, 2007, 2009 Delaware YRBS | High | Delaware | Victimization |

| Dunn et al. (2017) | 9300 | Sexual minoritized (gay, lesbian, bisexual, not sure) | 2009, 2011, 2013 Rhode Island YRBS | High | RI | Victimization |

| Duong & Bradshaw (2014) | 951 | LGB | 2009 NY YRBS | High | New York City, NY | Victimization; Victimization and Connectedness; Connectedness |

| Eisenberg et al. (2016) | 122,180 | LGBQ | 2013 Minnesota Student Survey | 8,9,11 | Minnesota | Victimization; Context |

| Espelage et al. (2008) | 13,921 | LGB | 2000 Dane County Youth Survey | High | Dane County, WI | Victimization and Climate; Victimization and Connectedness |

| Espelage et al. (2018) | 11,794 | LGBTQ | 2015 Dane County Youth Survey | High | Dane County, WI | Victimization; Safety |

| Evans-Campbell et al. (2012) | 447 | Two-sprit American Indian/Alaska Native | Targeted, partial network, and respondent-driven sampling | Adults (retrospective assessment of high) | NR | Context |

| Feinstein et al. (2019) | 18,515 | Bisexual | 2011–2015 YRBS | 9–12 | NR | Victimization |

| Friedman et al. (2006) | 96 | Gay males | Recruitment from gay community- or university-based organizations | Adults (retrospective assessment of elementary, middle, and high) | NR | Victimization |

| Goldblum et al. (2012) | 290 | Transgender | Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Survey | NR | Virginia | Victimization |

| Goodenow et al. (2006) | 202 | Sexual minoritized | 1999 Massachusetts YRBS | High | Massachusetts | Victimization; Connectedness; Processes; Safety; Context |

| Gower, Rider, Brown, et al. (2018) | 2168 | Transgender and gender diverse | 2016 Minnesota Student Survey | Grades 5, 8, 9, 11 | Minnesota | Safety; Connectedness |

| Hatchel, Merrin, & Espelage (2019) | 934 | LGBTQ | 2005 and 2007 YRBS (8 states and cities) | High | Midwest | Victimization and Climate; Climate |

| Hatchel, Ingram, et al. (2019) | 713 | LGBTQ | Randomized clinical trial of Sources of Strength | High | Colorado | Victimization; Connectedness |

| Hatzenbuehler (2011) | 31,852 | LGB | 2006–2008 Oregon Healthy Teens Study | Grade 11 | Oregon | Processes |

| Hatzenbuehler & Keyes (2013) | 31,852 | LGB | 2007–2008 Oregon Healthy Teens Study | Grade 11 | Oregon | Victimization; Processes |

| Hatzenbueler et al. (2014) | 55,559 | LGB | 2005 and 2007 YRBS; and 2010 School Health Profile | NR | Chicago, Delaware, Maine, MA, New York, NY, RI, San Francisco, VT | Processes and Structure |

| King et al. (2018) | 11,364 | LGBQ with disabilities | 2015 Youth Survey | High | Midwest | Victimization; Climate |

| LeVasseur et al. (2013) | 11,887 | LGB | 2009 New York City YRBS | High | New York | Victimization |

| Mereish et al. (2019) | 1129 | Black lesbian, gay, bisexual or mostly heterosexual | 2014 Youth Development Survey | Middle and high | NC | Victimization |

| Mueller et al. (2015) | 75,344 | LGB | 2009 and 2011 YRBS | High | National | Victimization |

| Perez-Brumer et al. (2017) | 946,743 | Transgender | California Healthy Kids Survey; California Student Survey | High | California | Victimization |

| Peterson & Rischar (2000) | 18 | High ability LGB | Recruitment from LGB support groups at 8 midwestern college or university campuses of highly selective institutions | Young adults (retrospective) | Midwest | Connectedness |

| Poteat et al. (2011) | 15,923 | LGBTQ | 2009 Dane County Youth Assessment | Grades 7–12 | Dane County, WI | Victimization |

| Poteat et al. 2013) | 15,965 | LGBTQ | 2009 Dane County Youth Assessment | Grades 7–12 | Dane County, WI | Processes |

| Proulx et al. (2019) | 47,730 | LGBTQ | 2015 State Level YRBS | High | US | Structure |

| Robinson & Espelage (2012) | 11,033 | LGBTQ | 2008–2009, Dane County Youth Assessment | Grades 7–12 | Dane County, WI | Victimization |

| Russell et al. (2011) | 245 | LGBT | Family Acceptance Project | Adults (retrospective assessment of high) | San Francisco, CA | Victimization |

| Seelman & Walker (2018) | 140,356 | LGBQ | 2005–2015 YRBS | High | US | Processes |

| Seil et al. (2014) | 8910 | LGB | 2009 NY YRBS | High | NY | Connectedness |

| Shields, et al. (2012) | 2154 | LGB | San Francisco 2009 YRBS | High | San Francisco, CA | Victimization |

| Taliaferro et al. (2018) | 922 | Bisexual | 2015 National YRBS | High | US | Victimization |

| Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp (2017) | 79,339 | LGBQ | 2013 Minnesota Student Survey | High | Minnesota | Victimization; Safety; Connectedness |

| Toomey et al. (2019) | 116,925 | Bisexual, mostly lesbian/gay, only lesbian/gay | Research Institute’s Profiles of Student Life: Attitudes and Behaviors (PSL-AB) survey data collected between June 1, 2012 and May 31, 2015 | Middle and high | US | Safety; Climate; Connectedness |

| Walls et al. (2008) | 182 | Sexual minoritized (LGBTQ) | Recruitment from LGBTQ Community Center | High | Denver, CO | Victimization; Connectedness; Processes |

| Walls et al. (2013) | 284 | Sexual minoritized (LGBTQ) | Recruitment from LGBTQ Community Center | Community center (retrospective) | Denver, CO | Processes |

Note. LGB = lesbian, gay, bisexual; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning/queer; NR = not reported; YRBS = Youth Risk Behavioral Survey.

Results

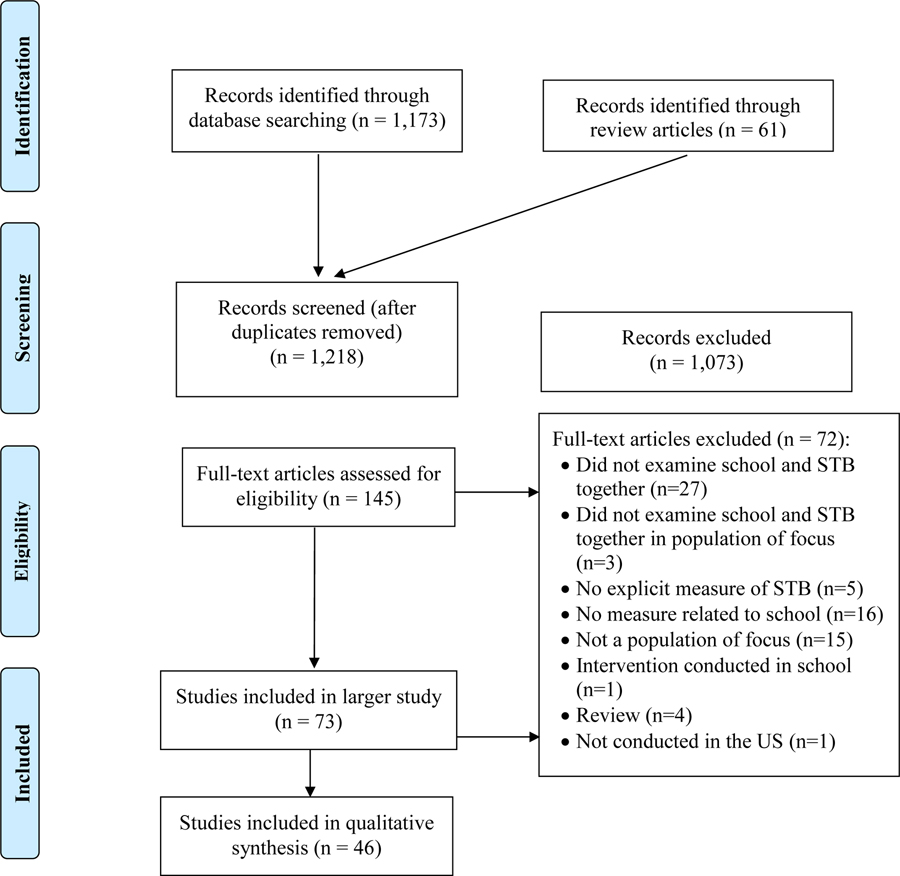

A total of 1,173 peer reviewed articles were identified based on the literature search and a total of 61 peer reviewed articles were identified by searching within published review articles selected for the larger review (see Supplementary Materials). After removing duplicates, a total of 1,218 records were reviewed by screening titles and abstracts, of which 1,073 were removed because it was clear that these studies did not meet eligibility criteria based on review of titles and abstracts alone. We reviewed the full text of the remaining 145 articles, of which 72 articles were excluded based on additional details presented in the body of the text. A total of 73 articles that examined LGBTQ+ and ethnic-racial minoritized students were maintained for the larger project. For the current study, an additional 27 studies were excluded because they focused on ethnic-racial minoritized youth and did not address LGBTQ+ youth specifically, resulting in a total of 46 articles for inclusion. See Figure 1 for PRISMA style flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram of School-Related Influences of Suicide-Related Thoughts and Behaviors in LGBTQ+ Youth

School Constructs

Findings are categorized according to the four components of school microsystems identified by the SVSC. Specifically, constructs represented either school climate (victimization, school safety, school connectedness, and broad measures of school climate), school processes, school context, or school structure. We present findings separately for subdomains of school climate (i.e., victimization, safety, and school connectedness and climate), due to their vast and robust literature base. Thus, we describe findings in four primary domains (one of which included four subdomains): (1) school climate, which included (1a) victimization, (1b) school safety, (1c) school connectedness and belonging, and (1d) broad measures of climate; (2) school processes; (3) school context; and (4) school structure.

Within the domain of school climate, a total of 31 studies explored victimization experiences, which included bullying, discrimination, and harassment. School safety was examined in seven studies and included experiencing fear at school, as well as school disciplinary practices. Studies exploring perceptions of school connectedness or belonging, and school climate more broadly, are presented together. Thirteen studies addressed some form of school belonging or connectedness (i.e., connectedness to in-school adults, perceptions of adult supports, in-school help-seeking, academic engagement, and parent involvement in education) and six studies measured school climate more broadly. Studies in the latter category typically measured multiple indicators of school climate, including a combination of some of the other sub-categories of school climate such as school safety and school connectedness. School processes (e.g., programs, policies, services) such as state-level anti-bullying laws and GSAs were examined in 10 studies. Finally, school context was explored in three studies exclusively exploring school demographics characteristics and school structure was explored in two studies in relation to health and sexual education curricula.

Victimization

Findings exploring queer students broadly (i.e., not disaggregated by specific LGBTQ+ identity within the queer umbrella) overwhelmingly supported a direct relationship between victimization and STB, with effect sizes ranging from small to large (Annor et al., 2018; Ballard et al., 2017; Barnett et al., 2019; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Bouris et al., 2016; Button, 2015; Button & Worthen, 2014; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Eisenberg et al., 2016; Espelage et al., 2018; Friedman et al., 2006; Goldblum et al., 2012; Goodenow et al., 2006; Hatchel, Ingram, et al., 2019; Hatchel, Marrin, & Espelage, 2019; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013; King et al., 2018; Poteat et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2011; Shields et al., 2012; Taliaferro et al., 2018; Walls et al., 2008). Multiple studies accounting for demographic characteristics and/or other significant predictors of STB (e.g., hopelessness, depressive symptoms, drug and alcohol use) also supported the significant negative effects of victimization on STB, with small to moderate effect sizes (e.g., Button, 2015; Goodenow et al., 2006; Perez-Brumer et al., 2017; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017; Walls et al., 2008). One study reported non-significant effects of victimization on suicidal ideation after accounting for other predictors (e.g., depressive symptoms, future drug use), although findings remained significant for suicide attempts (Hatchel, Ingram, et al., 2019). With exception (i.e., Walls et al., 2008), results also supported significant effects (small to moderate in size) when examining types of STB separately, including suicidal ideation and attempts, plans, and/or multiple types of attempts (e.g., with or without an injury; Barnett et al., 2019; Eisenberg et al., 2016; Goodenow et al., 2006; Hatchel, Ingram, et al., 2019).

Victimization by LGBTQ+ Identity

When disaggregated by LGBTQ+ identity, differences in victimization findings emerged. In a sample of nearly 80,000 ninth and eleventh grade students that included 4,960 LGBQ students, Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp (2017) found that bisexual and questioning youth with prior victimization experiences (e.g., bullying due to sexual orientation, school violence) were at increased risk of lifetime suicidal ideation or suicide attempts (effect size range: OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.11, 1.76] to OR = 2.74, 95% CI [1.68 to 4.48]); however, gay and lesbian students were not. The authors hypothesized that bisexual and questioning youth may be at heightened risk for negative psychological outcomes as these youth may face barriers to acceptance in both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ communities. In contrast, Button and Worthen (2014) found that, among 539 LGBQ youth and youth involved in same-sex behavior, school victimization experiences were significantly related to STB regardless of identity. Other studies (Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013) have supported significant effects of victimization on STB for individual LGBTQ+ groups; however, these studies did not explore differences between groups.

Explorations of gender and/or sex differences in the relationship between victimization and STB revealed mixed results. In one study, bullying victimization was significantly related to past year report of suicidal ideation for sexual minoritized girls but not for boys (DeCamp & Bakken, 2016). Results from another study supported an interaction effect between sex and victimization in predicting past year suicide attempts, with victimized LGB males exhibiting a higher risk for reporting an attempt than victimized LGB females (d = 1.3; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002). Nevertheless, in a separate study, Button and Worthen (2014) did not find a significant interaction effect for victimization and sex on STB in LGBTQ+ youth.

Finally, Feinstein et al. (2019) compared rates of suicidal ideation between White, Hispanic, and Black bisexual students, with and without accounting for bullying experiences. Although significant differences in suicidal ideation between White and Hispanic bisexual students were not supported, Black bisexual students were less likely to report suicidal ideation than White bisexual students, even after controlling for bullying (OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.41, 0.85]). Moreover, Hispanic bisexual students were more likely to report past year suicidal ideation compared to bisexual Black students with or without accounting for bullying (OR = 1.74, 95% CI [1.29, 2.34]; Feinstein et al., 2019).

LGBTQ+ Students Compared to Heterosexual Students

Studies exploring differences between STB outcomes in LGBTQ+ and heterosexual students experiencing victimization have also revealed mixed findings. Some studies have found that, as compared to heterosexual students, LGBTQ+ students are at greater risk for suicidal ideation (Dunn et al., 2017; King et al., 2018; Mueller et al., 2015), suicide plans (Shields et al., 2012), suicide attempts (Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002), and STB (Annor et al., 2018; Espelage et al., 2018). However, results from Dunn et al. (2017) indicated that although sexual minoritized girls experiencing any type of bullying were more likely to report past year suicidal ideation than heterosexual boys experiencing bullying (school bullying: adjusted OR [aOR] = 3.34, 95% CI [1.85, 6.04]; school and electronic bullying: OR = aOR = 2.86, 95% CI [1.65, 4.96]), sexual minoritized boys were only at increased risk relative to heterosexual boys when both school and electronic bullying were considered jointly (aOR = 2.56, 95% CI [1.38, 4.75]; Dunn et al., 2017).

Two studies reported no statistical differences between the two populations for STB (Barnett et al., 2019) or suicide attempts (Shields et al., 2012). Barnett and colleagues’ (2019) findings are particularly striking because the researchers explored anti-LGB victimization (i.e., harassment in school based on perceived gender or sexual orientation) and did not find differential effects of victimization on suicidal ideation, suicide plans, or suicide attempts in sexual minoritized youth when compared to heterosexual students. Additionally, Shields and colleagues (2012) found a significant interaction effect between sexual orientation and victimization (in or out of school), wherein heterosexual students exposed to victimization were at increased odds for reporting suicide plans (aOR = 3.0, 95% CI [2.0, 5.0]), but not suicide attempts, as compared to sexual minoritized students also reporting victimization.

Some of these differences may be due, in part, to LGBTQ+ status accounting for more variance than victimization experiences in predicting STB. For example, Robinson and Espelage (2012) found that, although victimization accounted for some disparities in suicide risk between LGBTQ+ and heterosexual students, LGBTQ+ status still accounted for some ideation and attempt risk. When analyzed by identity, status was significant for bisexual and questioning youth but not for lesbian, gay, or transgender youth (i.e., victimization better explained risk; Robinson & Espelage, 2012). When LGBTQ+ youth were matched with heterosexual peers with similar demographic and victimization profiles, they were still over 3 times more likely to consider suicide (OR = 3.32) and approximately 3 times as likely to report an attempt (OR = 2.95; Robinson & Espelage, 2012).

Similar findings emerged from a study exploring disparities in suicide risk between ethnic-racial minoritized LGBTQ+ students after accounting for bullying experiences. Specifically, Mueller and colleagues (2015) found that, as compared to White heterosexual individuals, Latinx and Black youth considered separately by race and LGBTQ+ group (i.e., gay males, lesbian females, bisexual males, and bisexual females) had higher odds of reporting past year suicidal ideation with small to moderate effect sizes, with or without accounting for bullying (effect sizes after accounting for bullying range from OR = 1.97, 95% CI [1.07, 3.65] to OR = 5.01, 95% CI [3.79, 6.62]; Mueller et al., 2015).

Finally, another explanation for mixed findings may relate to important differences between ethnic-racial groups. LeVasseur et al. (2013) reported that, among non-Hispanic sexual minoritized students and Hispanic heterosexual students, victimization was related to STB; however, this relationship was not significant for Hispanic sexual minoritized students.

Victimization as a Mediator

Several studies have modeled victimization as a mediator between LGBTQ+ status and STB. Two studies found small to moderate effect sizes for this model (Bouris et al., 2016; Perez-Brumer et al., 2017). Findings from another study did not support the model in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and questioning students (Ballard et al., 2017), and a fourth study found support for it, but findings varied by identity and type of STB (Mereish et al., 2019). More specifically, this last study found support for victimization as a mediator only for mostly heterosexual students, but not youth identifying as LGB, and only for some behaviors (i.e., planning; Mereish et al., 2019). This study was one of few specifically examining this relationship among Black sexual minoritized students.

Another study found that victimization mediated the relationship between masculinity and STB in middle school, suggesting students with low masculinity may be bullied and in turn experience STB (Friedman et al., 2006). Poteat and colleagues (2011) explored the indirect effects of bullying victimization on academic outcomes (i.e., grades, truancy, and the importance of graduating) through STB, finding support for this model in both ethnic-racial minoritized heterosexual students and LGBTQ+ students, as well as White heterosexual students, but not for White LGBTQ+ students. Interestingly, when examining homonegativity victimization specifically (although not in-school only), findings were the reverse for LGBTQ+ White and ethnic-racial minoritized students; that is, STB was a significant mediator for White but not ethnic-racial minoritized LGBTQ+ students.

Protective Factors against Effects of Victimization on STB

Regarding protective factors in the association of LGBTQ+ status and STB, school connectedness (feeling connected to an adult in school; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014) and positive school climate (Espelage et al., 2008; Hatchel, Merrin, & Espelage, 2019) have been shown to play a protective role (yielding small effect sizes) against the negative effects of victimization on STB in LGBTQ+ youth. Moreover, greater representation of LGBQ students in schools was shown to mitigate the negative effects of bullying experiences on suicide attempts for girls (but not boys; Eisenberg et al., 2016). Note, however, that findings reported by Eisenberg et al. (2016) did not support a significant interaction between the proportion of LGBQ students at the school-level and bullying victimization in predicting past year suicidal ideation.

In contrast to the protective effects of school connectedness and climate, parent and peer support were not shown to mitigate suicide-related risk of bullying victimization in a sample of adult gay men reporting on their school experiences retrospectively (Friedman et al., 2006) or in a school sample of LGB youth (Espelage et al., 2008). Thus, although peer and parental support may demonstrate protective effects against STB independently (Friedman et al., 2006), school-wide support may be especially important for mitigating the effects of victimization in LGBTQ+ students.

School Safety

A total of seven studies examined STB in relation to student perceptions of school safety, which included experiencing fear at school and perceptions of school disciplinary practices, in sexual minoritized students. Findings largely supported the protective role for feelings of school safety, with small effect sizes (Barnett et al., 2019; Goodenow et al., 2006; Gower, Rider, Brown et al., 2018; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017; Toomey et al., 2019). Although most of these studies explored student-level perceptions, Goodenow and colleagues (2006) used a school level indicator of safety (percent of tenth grade students perceiving their school as safe). Contrary to their expectations, the researchers found increased risk for suicide attempts with injuries for students in schools perceived to be safe (OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.85, 0.99]); however, significant differences were not supported for other measures of suicide attempts (those with or without an injury).

Safety by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Although only two studies explored the relationship between perceived school safety and STB in subgroups of sexual minoritized youth, findings differed based on sexual minoritized status. Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp (2017) found support for a reduced risk for suicidal ideation and attempts among gay and lesbian students who felt safe at school (suicidal ideation, OR = 0.63, 95% CI [0.47, 0.85]; suicide attempts, OR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.47, 0.91]) but not for bisexual or questioning students. However, Toomey et al. (2019) found that perceiving clear school boundaries (i.e., clear rules and consequences in school) was associated with reduced odds for suicide attempts among bisexual students (OR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.80, 0.97]) but not heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, mostly gay and lesbian, or gay and lesbian students.

LGBTQ+ Students as Compared to Heterosexual Students

Regarding differences between heterosexual and sexual minoritized students, findings differed according to types of safety concerns and sample characteristics. In a sample of predominantly Black students, Barnett and colleagues (2019) found that fear of school violence had a stronger effect on suicide planning for heterosexual students than sexual minoritized students (OR = 0.51, 95% CI [0.32, 0.80]); however, no differences in ideation or attempts were found between the two groups. In contrast, Espelage and colleagues (2018) found that, as compared to heterosexual students who perceived high levels of school violence and crime, LGBTQ+ students who perceived it demonstrated higher rates of STB; no differences in STB were found between heterosexual and sexual minoritized students perceiving low levels of violence and crime.

Safety as a Mediator

Only one study suggested that school safety may play a mediating role in the relationship between LGBTQ+ status and STB. Specifically, Bouris et al. (2016) found that skipping school due to safety concerns was a marginally significant mediator of the association between LGBTQ+ status and STB.

School Connectedness, Belonging, and Climate

In addition to studies exploring how school climate and connectedness may protect against the effects of victimization on STB, 16 studies explored how a form of school climate (i.e., belonging, or connectedness) related directly to STB. Specifically, studies addressed connectedness to in-school adults (k = 3), adult supports in school (k = 4), help-seeking behaviors or intentions in school (k = 4), academic engagement and parental involvement (k = 1), and broad measures of school climate (k = 5).

Connectedness to In-School Adults

Three studies explored how connectedness to adults may relate to STB. Although Seil et al. (2014) found that the highest rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in LGB students were among those reporting no connections to adults (suicidal ideation, OR=6.71, 95% CI [4.74, 9.52]; suicide attempts, OR=6.25, 95% CI [4.16, 9.38]), findings from other studies did not support a significant association between connectedness and STB (Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Gower, Rider, Brown, et al., 2018). More specifically, student-teacher relationships were not significantly related to ideation or attempts among transgender and gender diverse students when accounting for other significant predicters of suicide (e.g., other risk behaviors; Gower, Rider, Brown, et al. 2018). Additionally, in-school adult connections were not significantly related to suicide attempts (any, or serious) in LGB students (Duong & Bradshaw, 2014).

Adult Supports in School

Studies exploring the relationship between adult supports and STB in sexual minoritized students suggest small effects that may diminish when accounting for more salient predictors of STB. However, Goodenow et al. (2006) demonstrated that after controlling for student demographics, school characteristics, and emotional distress, support from school staff was significantly associated with reduced odds for past year report of two or more suicide attempts (OR = 0.19, 95% CI [0.06, 0.60]); this result was not found for one or more suicide attempts or attempts with injury. Coulter et al. (2017) found that school adult supports demonstrated a protective role in a combined sample of heterosexual and LGBTQ+ students; nevertheless, when results were stratified by sexual orientation, they were no longer significant for most sexual minoritized youth. However, within-school adult supports played a stronger protective role against suicidal thoughts (OR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.53, 0.91]) for bisexual youth than for heterosexual youth (OR = 0.76, 95% CI [0.59, 0.99]; Coulter et al., 2017). As compared with heterosexual youth, however, all LGBTQ+ groups were more likely to report suicidal ideation, plans, or attempts, even after accounting for in-school adult supports (Coulter et al., 2017).

Two other studies did not indicate a protective function of adult support. Button (2015) did not find a significant relationship between teacher support and STB. In this study, social support from teachers, peers, and friends explained only an additional 1.9% of the variance in STB for LGBQ youth but an additional 3.8% for heterosexual youth. Similarly, Walls et al. (2008) did not find a significant association between having an adult ally in school and contemplating suicide.

Help-Seeking Behaviors and Intentions in School

Three studies specifically explored help-seeking behaviors in relation to STB. Without controlling for other variables, bivariate correlations from two studies supported a significant relationship between help-seeking and STB. One of these studies found a significant association between in-school help-seeking behaviors and reduced rates of self-reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (yielding small effect sizes, r = −.18 and r = −.27, respectively; Hatchel, Ingram, et al., 2019). However, in the same study, help-seeking behaviors were no longer significant in predicting suicidal ideation or attempts after controlling for depressive symptoms, victimization, and future drug use; rather, they interacted with depressive symptoms such that LGBTQ+ youth with higher levels of both help-seeking and depressive symptoms were more likely to report past 6-months suicidal ideation (OR = 2.38, 95% CI [1.44, 3.49]). Colvin et al. (2019) found that both intention to seek help from a teacher for a personal problem and actually seeking help from a teacher were associated with intention to seek help from a teacher for suicidal ideation specifically (yielding moderate to large effect sizes, r = .57 and .48, respectively).

Regarding suicide disclosure to school adults, Peterson and Rischar (2000) conducted a qualitative study of 18 self-identified gifted LGB young adults and presented descriptive statistics regarding participants’ help-seeking behaviors in school. Of the 13 participants indicating they had suicidal ideation, 11 described discussing ideation with a friend, counselor, or both; none reported discussing it with a teacher (Peterson & Rischar, 2000). Finally, after controlling for other key variables (e.g., depressive symptoms, parent connectedness), Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp (2017) found that teacher caring was related to reduced odds for lifetime reported suicidal ideation (but not attempts) among questioning students (OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.85, 0.95]); however, teacher caring was neither related to ideation nor attempts among bisexual or gay/lesbian students.

Academic Engagement and Parental Involvement

Toomey et al. (2019) explored academic engagement and involvement in relation to STB in a sample of sexual minoritized youth. Academic engagement was not associated with lifetime history of suicide attempts for heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly gay or lesbian, or gay or lesbian students. Parental involvement in school, however, was significantly related to slightly lower odds of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt for youth identifying as heterosexual only (OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.91, 0.93]); significant differences were not supported for other sexual minoritized (mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly gay/lesbian, and only gay/lesbian) youth.

Climate

Five studies examined a broad measure of school climate in relation to STB, demonstrating largely positive effects. Positive school climate (i.e., “how much students feel that they are getting a good education at their school and are respected and cared about by adults at their school”; Birkett et al., 2009, p. 993) played a protective role in the relationship between LGBQ identity and past month suicidal ideation and/or depression (combined measure), with effects supported for both heterosexual and sexual minoritized students (Birkett et al., 2009). Two studies found support for positive school climate (measuring perceptions of school connectedness, safety, and belonging) in protecting against ideation in sexual minoritized youth (Hatchel, Merrin, & Espelage, 2019; King et al., 2018), but not against attempts (Hatchel, Merrin, & Espelage, 2019) and not for suicidal ideation in youth identifying as both LGBQ and with a disability (King et al., 2018).

Colvin et al. (2019) examined help-seeking intentions related to suicidal ideation, and found that bivariate correlations supported a significant relationship between positive perceptions of school climate (including a sense of a supportive learning environment, safety, respect for diversity) and intention to seek help from a teacher for suicidal thoughts (yielding a small effect size, r = .21;). Results remained significant after adjusting for demographic characteristics and presence of a GSA (β = 0.16, 95% CI [0.04, 0.29]). However, Toomey et al. (2019) found that having a caring school climate was significantly related to lower odds for reporting a lifetime suicide attempt for youth identifying as mostly heterosexual (OR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.78, 0.93]); nonetheless, this relationship was not supported for other sexual minoritized youth (i.e., heterosexual, bisexual, mostly gay/lesbian, only gay/lesbian youth).

School Processes

A total of 10 studies examined school processes in relation to STB in LGBTQ+ youth. Studies focused on the effects of GSAs (k = 5), state-level antibullying laws (k = 3), school social environments that accounted for programs and policies addressing inclusionary processes (k = 2), and other interventions or programs in school (k = 2).

Gender-Sexuality Alliances

Five of the studies that examined school processes (e.g., interventions, policies) in relation to suicide risk explored the protective effects of GSAs (identified sometimes by researchers as Gay-Straight-Alliances or sexual minoritized support groups, which we refer to as Gender and Sexuality Alliances) on STB. Findings reported by Walls et al. (2008) indicated a protective role of GSAs or sexual minoritized support groups against considering or making a suicide attempt (OR = 0.38, SE = 0.20) and suicide attempts alone (OR = 0.48, SE = 0.20), even after controlling for other key predictors of suicide (e.g., hopelessness, drug and alcohol use). Findings reported by Poteat et al. (2013) suggest that GSAs were protective against suicidal ideation and attempts in a sample of both heterosexual and sexual minoritized students. Moreover, GSAs demonstrated greater protective effects for suicide attempts (but not suicidal ideation) in sexual minoritized youth as compared to heterosexual youth. Findings from Walls et al. (2013) supported a protective effect of GSAs on suicide attempts (16.9% of LGBTQ+ students attending schools with GSAs as compared to 33.1% attending schools without GSAs reported past year suicide attempts) but only trend level effects for suicidal ideation.

Although Goodenow et al. (2006) found that LGB support groups were associated with reduced odds for reporting two or more suicide attempts (OR = 0.29, 95% CI [0.10, 0.85]), effects did not remain significant after accounting for the effects of other school-related factors (i.e., victimization, perceived staff support, and antibullying policies). Likewise, after adjusting for demographic characteristics, having a GSA was not significantly related to intention to seek help from a teacher for suicidal thoughts (Colvin et al., 2019). Taken together, findings suggest that GSAs may be most beneficial for protecting against suicide attempts, but implementation requires attention to school-level factors such as student-body demographics.

Anti-Bullying Policies

Three studies specifically examined school- or state-level antibullying policies in relation to STB, with two reporting that effects varied by degree of inclusivity. Inclusive or enumerated anti-bullying policies specifically identify protected groups, including LGBTQ+ youth. Results reported by Hatzenbuehler and Keyes (2013) did not indicate significant effects of inclusive antibullying policies on STB for heterosexual and bisexual youth; however, they did indicate significant effects for lesbian and gay students. Specifically, lesbian and gay youths living in the least inclusive counties were more than twice as likely to report a past year suicide attempt than those in the most inclusive counties (OR = 2.25, 95% CI [1.13, 4.49]). In a final model adjusting for peer victimization and sociodemographic characteristics, inclusive anti-bullying policies remained significantly associated with lower risk for past year suicide attempts among lesbian and gay students (OR = 0.18, 95% CI [0.03, 0.92]). Districts identified as exhibiting a “medium” degree of inclusivity were also compared to the most inclusive districts but did not have a significant impact on STB for gay, lesbian, or bisexual youth. Note that in a follow-up analysis of both inclusive and restrictive anti-bullying policies, these findings were not significant (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013).

Findings from Seelman & Walker (2018) did not support the protective effects of general state-level antibullying laws against attempts in LGB and questioning youth; however, the researchers did report a protective effect of enumerated (sexual orientation inclusive) antibullying laws when LGB and questioning youth were explored together (leading to a reduction in suicide attempts by 3.3%). Finally, Goodenow et al. (2006) found that having an anti-bullying policy was related to reduced odds of having made one suicide attempt (OR = 0.37, 95% CI [0.16, 0.86]) and multiple suicide attempts (OR = 0.16, 95% CI [0.03, 0.81]) but not of having made a suicide attempt with injuries. Taken together, findings highlight the importance of inclusive anti-bullying policies for lesbian and gay youth.

School Social Environments

Two studies (Hatzenbueler, 2011, 2014) examined an aggregate measure of school social environments accounting for programs and policies such as the presence of GSAs and school-level nondiscrimination and antibullying policies. Hatzenbueler (2011) found that, although social environments did not fully mediate the relationship between LGB status and suicide attempts, LGB youth in homonegative environments were 20% more likely to report a suicide attempt than those in positive environments (compared to a 9% increase for heterosexual youth).

Hatzenbueler et al. (2014) explored differences in jurisdictions based on school climate, defining schools with positive climates as having GSAs, including curricula on health matters relevant to LGBTQ+ youths, prohibiting harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity, encouraging staff to attend trainings on supportive LGBTQ+ environments, and facilitating access to community providers serving LGBTQ+ youths. For gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth, but not heterosexual or questioning students, living in a jurisdiction with a positive school climate was associated with a lower likelihood of past year suicidal ideation (OR = 0.68, 95% CI [0.47, 0.99]; OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.66, 0.99], respectively) but not suicide planning or attempts.

Other Programs and Interventions

Peer-tutoring programs were associated with reduced odds of reporting a suicide attempt when controlling for student demographics and school characteristics (OR = 0.57, 95% CI [0.32, 0.99]), but this relationship was no longer significant in a final model also accounting for distress and victimization (Goodenow et al., 2006). In the same study, numerous other interventions were explored but did not significantly relate to STB outcomes; these interventions included sexual harassment training, student court, monitoring at-risk students, psychological counseling, and other peer-support groups (Goodenow et al., 2006). Notably, Goodenow and colleagues (2006) also found that participation in service learning was actually related to higher reports of past year suicide attempts (OR = 3.11, 95% CI [1.00, 9.65]), but results were not significant for two or more suicide attempts or attempts resulting in an injury.

School Context

School demographic characteristics were explored in two studies, yielding small effect sizes. In a study exploring the proportion of LGBQ students in schools as a predictor of STB, greater presence of LGBQ students was significantly related to reduced reports of past year suicide attempts (but not ideation) for LGBQ girls (aOR = 0.84, 95% CI [0.72, 1.00]) but not boys (Eisenberg et al., 2016). Goodenow and colleagues (2006) found that past year suicide attempts and two or more suicide attempts were less commonly reported by youth attending more ethnically diverse schools (OR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.97, 1.00]; OR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.95, 1.00], respectively), and two or more suicide attempts were also more common in schools with higher rates of poverty (OR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.95, 1.00]); however, significant differences were not found for “any” attempts or attempts with injuries. No differences in STB were found in comparing (a) suburban and urban, (b) rural and urban, or (c) vocational and comprehensive districts/programs.

Finally, in the only study to explore school context in two-spirit American Indian and Alaskan Native students, Evans-Campbell and colleagues (2012) found that attending a boarding school was associated with increased lifetime suicidal ideation and making a suicide attempt. Having a caretaker who attended boarding school was also significantly related to lifetime ideation (but not attempts). Note that findings should be considered within the historical and sociopolitical context of the treatment of Indigenous communities, with boarding schools representing both school context and oppressive policies resulting in the forced removal of Indigenous youth from reservations into boarding schools.

School Structure

Two studies explored health and sexual education curricula in relation to STB in LGBTQ+ students. As described previously, lesbian and gay students (OR = 0.68) and bisexual students (OR = .81), but not questioning students, living in jurisdictions with a positive social climate (defined to include both GSA and health curricula relevant to LGBTQ+ youth, among other factors) were less likely to report past year suicidal ideation (Hatzenbueler et al., 2014). Note, however, that confidence intervals were relatively wide, indicating heterogeneity within groups. Finally, Proulx and colleagues (2019) examined the effects of inclusive sexual education programs and reported that for both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ students, inclusive programs played a protective role against both ideation and suicide plans (aOR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.89, 0.93]; aOR = 0.79, 95% CI [0.77, 0.80], respectively); results did not differ significantly for LGBTQ+ and heterosexual students.

Discussion

Findings from this systematic review reinforce the importance of cultivating an inclusive and positive school environment for LGBTQ+ youth. Multiple school-related factors (e.g., bullying, perceived safety, school climate, school processes, school structure) hold the potential to influence STB. Findings also suggest several differences in the strength of these relationships across individuals (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity) and environments (e.g., demographic characteristics of student bodies, school rules, state policies). Therefore, it remains important to consider multiple indicators of school-related protective and risk factors for LGBTQ+ youth. That is, no single intervention or action alone will prevent STB, and efforts for fostering positive student experiences must span multiple layers of a student’s ecology.