Abstract

Chemical respiratory sensitization is an immunological process that manifests clinically mostly as occupational asthma and is responsible for 1 in 6 cases of adult asthma, although this may be an underestimate of the prevalence, as it is underdiagnosed. Occupational asthma results in unemployment for roughly one-third of those affected due to severe health issues. Despite its high prevalence, chemical respiratory sensitization is difficult to predict, as there are currently no validated models and the mechanisms are not entirely understood, creating a significant challenge for regulatory bodies and industry alike. The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) for respiratory sensitization is currently incomplete. However, some key events have been identified, and there is overlap with the comparatively well-characterized AOP for dermal sensitization. Because of this, and the fact that dermal sensitization is often assessed by in vivo, in chemico, or in silico methods, regulatory bodies are defaulting to the dermal sensitization status of chemicals as a proxy for respiratory sensitization status when evaluating chemical safety. We identified a data set of known human respiratory sensitizers, which we used to investigate the accuracy of a structural alert model, Toxtree, designed for skin sensitization and the Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health (COEH)’s model, a model developed specifically for occupational asthma. While both models had a reasonable level of accuracy, the COEH model achieved the highest balanced accuracy at 76%; when the models agreed, the overall accuracy was 87%. There were important differences between the models: Toxtree had superior performance for some structural alerts and some categories of well-characterized skin sensitizers, while the COEH model had high accuracy in identifying sensitizers that lacked identified skin sensitization reactivity domains. Overall, both models achieved respectable accuracy. However, neither model addresses potency, which, along with data quality, remains a hurdle, and the field must prioritize these issues to move forward.

INTRODUCTION

Occupational asthma is one of the most common occupational lung diseases, and it represents a significant cause of morbidity and occasionally mortality. It is responsible for 1 in 6 cases of adult asthma; however, this is likely an underestimate, as occupational asthma is considerably underdiagnosed.1–3 Approximately one-third of workers with occupational asthma will be forced into unemployment due to severe health issues, which results in lost wages and lost productivity.3,4

Occupational asthma can be induced by a chemical respiratory sensitizer (often called “sensitizer-induced occupational asthma” or “allergic occupational asthma”) or a chemical irritant agent (irritant-induced occupational asthma).5 Allergic occupational asthma can be caused by either a high (HMW) or low-molecular-weight (LMW) chemical—the former is commonly seen in occupational settings where individuals are exposed to enzymes or other biological material, especially over a lengthy period of time, and often includes the development of specific IgE antibodies.6 In contrast, LMW chemical-induced asthma can include non-IgE-mediated responses resembling T lymphocyte-mediated hypersensitivity reactions.7 Here, we will focus on LMW chemical-induced respiratory sensitization.

Despite the high prevalence of these clinical conditions, accurately identifying chemical respiratory sensitizers remains a challenge.8 There are no validated in vivo, in vitro, or in silico methods to identify chemical respiratory sensitizers. One approach has been to employ the local lymph node assay (LLNA)9,10 —a test commonly used to characterize dermal sensitizers—in part based on the assumption that there is a common sensitization mechanism.11 However, the LLNA has many limitations: it cannot distinguish a dermal sensitizer from a respiratory sensitizer, and the only approved route of application for the LLNA is dermal,12 making it of limited use for substances that are typically inhaled. It also does not reflect potential differences in tissue ADME for skin versus lung13 — this is in addition to the known challenges of the LLNA in general in terms of reproducibility.14,15 Mice, as well as other animal models, such as guinea pigs, have also been used to measure serum IgE levels and carry out cytokine fingerprinting, which allows for the distinction of a respiratory sensitizer from a dermal sensitizer;9,10 however, the role of IgE in chemically induced respiratory sensitization is not consistent, especially for lower-molecular-weight compounds.16,17 Further, results of animal experiments do not always translate to humans,18–21 as supported by the lack of accuracy in the LLNA to characterize sensitization in humans.22

Consequently, in vitro approaches have been employed, such as reconstituted human bronchial and nasal epithelium, coculture models, the direct peptide reactivity assay (DPRA), and the Genomic Allergen Rapid Detection (GARD) Assay.23–25,7,26 However, these also have their own set of limitations. For example, reconstituted respiratory epithelial tissues may not account for respiratory sensitization induced through other routes of exposure (e.g., dermal).17 In addition, although it has been proposed that the DPRA be modified for respiratory sensitization by incorporating a Lys:Cys ratio,27 its inability to consistently identify respiratory sensitizers means it cannot be used as a standalone tool.27,28 Finally, there are limited data sets for these models.

The inability to quickly identify potential respiratory sensitizers with a high degree of specificity is especially problematic for chemicals with widespread occupational inhalation exposure and, additionally, makes the diagnosis of occupational asthma difficult: the molecular etiology of most cases of occupational asthma is not definitively determined, which makes identification and treating occupational asthma especially difficult, as the main treatment is to avoid re-exposure.29 The lack of a validated gold-standard assay for respiratory sensitization makes the development of an in vitro or in silico model that can quickly determine sensitization potentially challenging, as does the lack of a complete adverse outcome pathway (AOP) with clearly identified key events.

Indeed, the AOP for respiratory sensitization30 is currently incomplete; however, the molecular initiating event as well as some key events have been identified. Several of these events overlap with the AOP for dermal sensitization, namely, the molecular initiating event: covalent binding of the chemical to a protein.11 The mechanism for dermal sensitization has been largely unraveled,31 and there is a substantial body of chemicals with known dermal sensitization status.32,33 Further, dermal sensitization status can be easily ascertained by in vivo or in vitro assays. Consequently, regulatory bodies are defaulting to the dermal sensitization status of chemicals as a proxy for respiratory sensitization status when evaluating chemical safety and, additionally, have no way to distinguish the respiratory potency of a potential sensitizer.34

While this approach is protective of human health, there are also points of divergence between the dermal and respiratory sensitization AOPs.11 For example, chemical respiratory sensitizers preferentially bind to lysine, while chemical dermal sensitizers bind to cysteine.27 Therefore, it remains unclear whether dermal sensitization is a suitable surrogate for respiratory sensitization in humans.

Previous studies have shown that combining structural alerts and computational models can result in accurate predictions;35 however, they focused on commercially available software or models that were not widely accessible. Here, we wanted to focus on two easily available, public domain models, Toxtree, which is intended to look for structural alerts to identify chemical skin sensitizers, and the COEH model,36 which predicts chemical respiratory sensitization status. To this end, we have (i) identified several data sets of human chemical respiratory sensitizers in the literature to characterize the data availability for human chemical respiratory sensitizers as well as the likely data gaps, and (ii) evaluated the accuracy of using Toxtree, a structural alert system designed to identify potential reactivity domains that may lead to skin sensitization, with the COEH model, a logistic regression model that computes an occupational asthma hazard index for a chemical based on its structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data.

To establish a data set of human chemical respiratory sensitizers, the search term “respiratory sensitization” was used in the Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) to identify chemicals with respiratory sensitization outcomes in humans. To expand our data set, we adopted a search strategy similar to a population, exposure, comparison, and outcome (PECO) literature search strategy (see Supplemental Table 1): occupational workers with inhalation exposure to chemical respiratory sensitizers that do or do not experience respiratory sensitization. We used this as a scoping review to examine the literature; while most papers were focused on instances of single chemical exposure or occupational surveillance, this ultimately helped us identify 5 papers that collected larger data sets specifically on low-molecular-weight chemicals. Once the data set was gathered, chemicals were assigned a Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number (CASRN) (if one was not identified within its respective reference) using the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s ChemIDplus Advanced chemical identifier system by entering the chemical name, as identified in the reference. If a CASRN was not available in either the reference or ChemIDplus Advanced, the chemical was excluded from the combined data set. CASRNs were then used to identify simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings also using ChemIDplus Advanced. If a SMILES string was not available, the chemical was excluded from the combined data set.

Once the data set was established, each chemical was assigned a chemical category using the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) Toolbox’s U.S. EPA New Chemicals Category profiler to determine whether there were patterns in the data by chemical class. This profiler was selected because these chemical categories are those that are used by the U.S. EPA when assessing the hazards of chemicals.37,38 Additionally, the distribution of the skin sensitization reactivity alerts for the overall data set was assessed using Toxtree; the “skin sensitization reactivity domains” decision tree was used.39

Classification, Labeling, and Packaging (CLP) data were taken from the C&L inventory database.40

Models.

The Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health’s (COEH) Chemical Asthma Hazard Assessment Program, a logistic regression model, was used to predict the respiratory sensitization potential of all chemicals in the data set (COEH undated). The model assigns a hazard index, which falls between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating the model is confident that the chemical is an occupational respiratory allergen. It provides results as “Hazardous”, “Borderline, may be hazardous”, and “Low index, may still be hazardous”. Two different approaches were taken to assess the performance of the COEH model. First, in addition to any chemical designated “Hazardous”, those chemicals assigned the prediction “Borderline, may be hazardous” were considered to be respiratory sensitizers, while chemicals designated with the term “Low index, may still be hazardous” were considered to be nonrespiratory sensitizers. This approach was termed “COEH (Conservative)”. For the second approach, referred to as “COEH (Not Conservative)”, any chemical predicted to be “Borderline, may be hazardous” was this time considered to be a nonrespiratory sensitizer along with those designated “Low index, may still be hazardous”, while only the “Hazardous” chemicals were considered to be respiratory sensitizers.

Additionally, Toxtree, a structural alert model, was used to predict the skin sensitization potential of all chemicals to determine if skin sensitization is a suitable proxy for respiratory sensitization.39 When predicting skin sensitization potential using Toxtree, the “skin sensitization reactivity domains” decision tree was used. Model performance for both models was assessed based on accuracy and balanced accuracy, as the data sets were slightly unbalanced. Additionally, other performance metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, false positives, and false negatives, were also evaluated.

Visualization.

Chemical similarity maps were calculated based on Tanimoto distance as calculated by the Score Matrix Service in PubChem.41 Chemicals with a Tanimoto distance of 0.80 or greater were considered as a link in the network; the network was visualized using degree-sorted circle layout in Cytoscape.42

RESULTS

Previously, we used HSDB to identify human skin sensitizers to evaluate various in silico models for predicting sensitization potential.33 Here, we adopted a strategy similar to our approach used in Golden et al.33 to identify respiratory sensitizers within HSDB. This search identified 128 chemicals with the term “respiratory sensitization” in their dossiers; however, only 22 chemicals had sufficient data to characterize respiratory sensitization hazard in humans. Either the remaining 106 chemicals only had respiratory sensitization data based on animal studies, or it was not clear how the respiratory sensitization status was determined; therefore, these 106 chemicals were excluded from this study. Of these 22, 19 were positive. Although we cannot be certain that this is indicative of lack of data, given the prevalence of occupational asthma, it is likely many potential respiratory sensitizers are not identified as such, and very few chemicals can be definitively ruled out as not being respiratory sensitizers.

Indeed, the lack of results in HSDB search may be attributable to inconsistent terminology use. Instead of the term “respiratory sensitization”, which is the term used in hazard labeling—such as the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) or the CLP regulation—to characterize this hazard endpoint in humans, we observed that clinical terms were much more commonly used. For example, 11 of the 128 chemicals had summaries that contained the term “hypersensitivity pneumonitis”. In addition, 4 chemicals had summaries that contained the term “occupational asthma”. The term “asthma” was used as a standalone term—albeit in the context of occupational exposure—most frequently: 18 chemicals used this term, although this does not distinguish between immune-related illnesses and, therefore, may include chemicals that are irritants, which may cause confusion in the literature as well as in the models.

When we evaluated the use of these terms in the broader biomedical literature, respiratory sensitization was the least common term used, while occupational asthma was by far more common. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the average number of new publications per year by decade with these terms in PubMed, a biomedical database.

Figure 1.

Use of terms to describe respiratory sensitization conditions. The figure presents the average number of new articles per year in PubMed by decade that contain the search terms commonly used to describe respiratory sensitization and related conditions. Please note that the average number of articles for Respiratory Sensitization from 1970 to 1979 was 0 and, therefore, is not included in the chart. The number of articles overall is increasing each decade, with occupational asthma being the most frequently used term and respiratory sensitization being the least frequently used term.

Over time, the number of overall publications regarding respiratory sensitization and related terms have increased dramatically, especially since 1980. This can likely be attributed to the establishment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1971, which began to prioritize worker health and safety.43 Additionally, there has been some shift in terminology over time, as the term “extrinsic allergic alveolitis” has lost favor compared to “hypersensitivity pneumonitis”. While these two terms are synonyms, there has been a shift in usage in the medical field.

In our scoping search in PubMed, we identified four robust human respiratory sensitization data sets44–47 and one list of well-accepted respiratory sensitizers27 in the literature. Chemicals were designated as either a sensitizer or non-sensitizer based on human data; potency was not considered in any of the data sets. The data sets are described in Table 1, below, and the complete chemical data set is provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of Data Setsa

| description | ||

|---|---|---|

| data set | sensitizers | non-sensitizers |

| Graham et al.44 | Chemicals in the medical literature meeting the “Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma” | Dermal non-sensitizers |

| Jarvis et al.45 | Chemicals in the medical literature with confirmed case reports of occupational asthma | n/ab |

| Enoch et al.46 | Chemicals in the medical literature with physician-confirmed case reports of occupational asthma | Chemicals that had no case reports of occupational asthma, but had established workplace exposure limits |

| Seed et al.47 | Chemicals in the medical literature with physician-confirmed case reports of occupational asthma or hypersensitivity pneumonitis | n/a |

| Lalko et al.27 | Chemicals representative of the most common classes of chemicals associated with respiratory allergy | n/a |

| HSDB | Chemicals associated with a positive respiratory sensitization response in humans | Chemicals explicitly stated as lacking a positive respiratory sensitization response in humans |

Four highly curated chemical respiratory sensitizer data sets (Graham et al. (1997); Jarvis et al. (2005); Enoch et al. (2012); and Seed et al. (2015)), one list of well-accepted respiratory sensitizers (Lalko et al. (2012), and one screening level data set (HSDB) were combined and used as the overall data set for this analysis.

A set of 301 controls was mentioned in this reference; however, the data were not publicly available, so these controls were not included in this analysis.

Graham et al.44 identified chemical respiratory sensitizers by reviewing the medical literature and classifying chemicals that met the “Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma”. No negative reports were identified for any chemicals using this approach, so the authors used dermal non-sensitizers as their respiratory non-sensitizers. Jarvis et al.45 took a similar approach: they identified respiratory sensitizers by reviewing medical literature and designated chemicals with physician-confirmed case reports of occupational asthma as respiratory sensitizers. A set of controls were also established by these authors by identifying chemicals with established occupational exposure limits and had established hazard profiles that lacked positive respiratory sensitization outcomes; however, these chemicals were not publicly available. Likewise, Enoch et al.46 examined the medical literature for physician-confirmed cases of occupational asthma to identify respiratory sensitizers. Further, they created a set of controls by confirming the chemicals did not cause occupational asthma yet had established occupational exposure limits; this approach ensures exposure has occurred and, because no cases of occupational asthma have been reported, it is very likely that the chemical will not induce a positive respiratory sensitization outcome. As in the previous three data sets, Seed et al.47 identified chemicals with confirmed cases of occupational asthma in the medical literature; however, they also included the term “hypersensitivity pneumonitis” to identify respiratory sensitizers for their data set. Lalko et al.27 identified respiratory sensitizers by selecting chemicals from classes of chemicals that are well-accepted respiratory sensitizers. Finally, we established the HSDB data set—a hazard screening level data set—as described earlier. Notably, these data sets mainly use similar approaches to identify positive respiratory sensitizers; however, the approaches to identify negative respiratory sensitizers vary greatly.

Table 2 presents the distribution of sensitizers versus non-sensitizers in each of the data sets. The six data sets were combined to create one data set totaling 519 chemicals; however, some chemicals lacked necessary chemical identifiers, and there was substantial overlap among data sets. Chemicals without a CASRN and SMILES string were not included in the final data set, and duplicate chemicals were removed by eliminating duplicate CASRN to produce a combined data set of 257 discrete chemicals (referred to throughout this document as the discrete chemical data set). If a sensitization call differed between two data sets, the chemical was designated as a sensitizer. The combined data set was slightly skewed in favor of sensitizers, but a considerable number of nonsensitizing chemicals were also identified.

Table 2.

Number of Sensitizers and Non-sensitizers among Data Setsa

| total | sensitizers | non-sensitizers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| data set | n | n | % | n | % |

| Graham et al.44 | 80 | 40 | 50 | 40 | 50 |

| Jarvis et al.45 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Enoch et al.46 | 186 | 104 | 56 | 82 | 44 |

| Lalko et al.27 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Seed et al.47 | 111 | 111 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| HSDB | 22 | 19 | 86 | 3 | 14 |

| all data sets | 519 | 394 | 76 | 125 | 24 |

| discrete chemicals from all data sets | 257 | 141 | 55 | 116 | 45 |

Sensitizers and non-sensitizers, as identified in the literature, among all data sets. The “All Data Sets” line represents the number of chemicals found in all data sets, while the “Discrete Chemicals from All Data Sets” row represents the number of chemicals once duplicates were removed. Overall, there were more sensitizers than non-sensitizers; however, when combining the data sets and removing duplicate chemicals, the data set was relatively balanced, but still with more sensitizers than non-sensitizers.

When looking at the overlap between reported human skin sensitization in HSDB and harmonized CLP notifications from ECHA in our previous work, we found a high degree of overlap.33 However, when we compared the substances identified as respiratory sensitizers based on harmonized CLP data (n = 191) to the current data set (n = 257), there was relatively little overlap (17 chemicals). In fact, of the 191 chemicals identified as respiratory sensitizers, over half were metals, and many of the remaining chemicals were read-across based on a handful of known chemical categories (see Supplemental Figure 1). In contrast, of the 4600 notified substances in the CLP, there were nearly 1400 identified as skin sensitizers—7 times the number of respiratory sensitizers—likely reflecting the fact that LLNA or guinea pig maximization test (GPMT) testing is a requirement of many regulatory regimes, and skin sensitization potential is identified more proactively. While we do not know the true number of respiratory sensitizers, the data suggest respiratory sensitization might be less likely to be correctly identified, especially since respiratory sensitization status is often based on skin sensitization status.

In order to characterize the chemical diversity of the data set, we calculated Tanimoto distance and developed a chemical similarity network by linking any chemical with a similarity greater than 0.80. CIDs were unavailable for 6 of the 257 chemicals, so the chemical similarity network was built from 251 chemicals. By this criterion, 110 of the 251 discrete chemicals had at least 1 structurally similar “neighbor”. Therefore, the majority of the data set (141 chemicals) had no chemical sufficiently similar for most read-across approaches, indicating a chemical diversity that would be a challenge for most QSARs. Figure 2 shows the chemicals clustered by similarity with sensitization status indicated by color, and not surprisingly, the two largest clusters represent chemical classes (phthalates and cyanates) which are well-described in the literature and known classes of chemical sensitizers. The distribution of nearest neighbors is presented in Table 3, below.

Figure 2.

Chemical similarity map for the discrete chemical data set. Chemicals in green are non-sensitizers and chemicals in red are sensitizers. Cluster 1 is a mixture of esters (primarily phthalates), Cluster 2 includes isocyanates and other nitrogen-containing compounds, and Cluster 3 contains penicillins and their salts.

Table 3.

Neighbor Distribution among Chemicalsa

| number of neighbors | number of chemicals |

|---|---|

| 0 | 141 |

| 1 | 51 |

| 2 | 16 |

| 3 | 12 |

| 4 | 2 |

| ≥5 | 29 |

Summary of the number of chemicals by neighbor using a Tanimoto distance of 0.80. Over half of the data set had no neighbors, and 20% had only 1 neighbor. Only 10% of the chemicals in the discrete data set had 5 or more neighbors. Only 251 of the 257 chemicals had a chemical identifier (CID) in PubChem. The 6 chemicals without a CID could not be assessed for structural similarity to the other chemicals in the data set, so they are not included in this table.

The largest cluster (Cluster 1) is a mixture of esters—primarily phthalates—and most chemicals in this cluster are nonsensitizing. The second largest cluster (Cluster 2) consists of nitrogen-containing compounds including many isocyanates, but also structurally similar, but nonsensitizing nitro- and amine-containing chemicals, representing an activity cliff from the perspective of a read-across approach. The third largest cluster (Cluster 3) contains penicillins and their salts, and these chemicals are all respiratory sensitizers. Supplemental Figure 2 provides numerical identification for all the clusters, and Supplemental Table 3 identifies the individual chemicals in each of the clusters, as well as those that had no neighbors (and, therefore, were not included in the chemical similarity map).

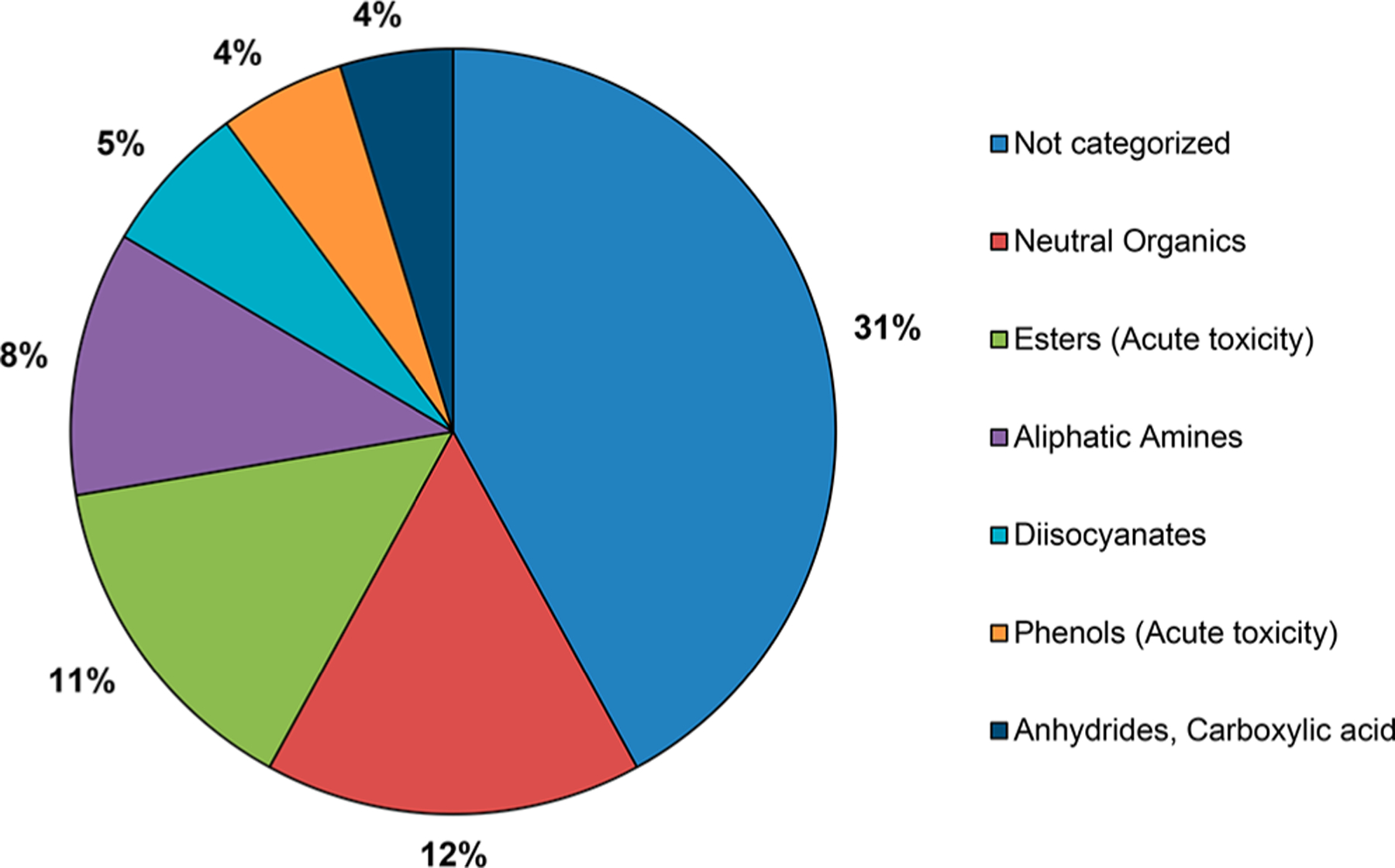

Additionally, each chemical was assigned to a chemical category using the U.S. EPA New Chemicals Category profiler in OECD QSAR Toolbox. The distribution of the discrete chemical data set by chemical category is presented in Figure 3. Almost one-third of the chemicals were not categorized, followed by neutral organics (12%), esters (acute toxicity) (11%), and aliphatic amines (8%).

Figure 3.

Chemical category distribution. Chemical categories were assigned using OECD QSAR Toolbox. Nearly one-third of chemicals were not categorized, as they did not fall under the definition of any of the U.S. EPA New Chemicals Categories. Of the chemicals that were categorized, the largest categories were neutral organics, esters (acute toxicity), and aliphatic amines. Chemicals categories that account for less than 4% of the total chemical category distribution have been omitted for clarity.

When compared to the distribution of skin sensitizing chemicals from our previous work,33 there were some similarities, such as the fact that the majority of chemicals were not categorized, and those that were categorized were largely neutral organics or esters (acute toxicity). However, there were some notable differences: the skin sensitization data set contained a higher percentage of aldehydes, while the respiratory sensitization data set chemical category distribution contained more diisocyanates and anhydrides. These differences are not surprising, as many aldehydes are well-established dermal sensitizers,48,49 while diisocyanates and anhydrides are established respiratory sensitizers.23 This suggests there might be some bias toward chemical classes with known sensitization mechanisms in the data sets, likely reflecting both publication bias toward positive results50,51 and the methodologies used to construct the data sets.

When analyzing the discrete chemical respiratory sensitization data set with Toxtree, the accuracy and balanced accuracy were relatively high (both 71%, see Figure 4), considering the model was designed to flag skin sensitization structural alerts. The COEH model had a balanced accuracy of 72% and 76% with the conservative and nonconservative approaches, respectively, indicating a modest benefit from its approach of focusing on known respiratory sensitizers. While the COEH model using the conservative call and the Toxtree model had similar distribution of false negatives and false positives, the COEH model with the nonconservative option had a small improvement in false positives (see Supplemental Table 4)—therefore, the COEH model had a higher accuracy and balanced accuracy when a less conservative approach was taken (i.e., borderline respiratory sensitizers were assigned as nonsensitizing).

Figure 4.

Accuracy of Toxtree vs COEH. Model performance was assessed using accuracy and balanced accuracy. COEH performed better than Toxtree at predicting respiratory sensitization outcomes, but minimally. Toxtree performed almost identically to COEH when a more conservative approach was used (i.e., when borderline sensitizer results from COEH were considered sensitizers). Toxtree did not perform quite as well as the COEH model when borderline chemicals were considered non-sensitizers (i.e., COEH Not Conservative results).

Interestingly, when we considered the results of the two models combined (using the nonconservative approach for the COEH results), the models agreed on 160 chemicals of the data set, and the overall accuracy when the models agreed was quite high: 87%, suggesting that combining the predictions is useful in a weight-of-evidence approach and potentially for an Integrated Testing Strategy.52

Figure 5a,b displays the chemical similarity map with mispredictions identified for Toxtree and COEH (less conservative option), respectively, showing both similarities and difference between the models depending on cluster. While both models correctly classified all of cluster 3, this cluster consists of penicillins as well as penicillins salts, which usually have the same hazard due to their high structural similarity53 (including both sets of these chemicals likely inflates the accuracy of the models, albeit modestly, as there were only 5 sets of parents and salts, but this does highlight the importance of clear chemical identification). Cluster 2 was predicted perfectly by Toxtree and nearly perfectly by the COEH model; this is not surprising as it is well-accepted that isocyanates are both chemical respiratory and dermal sensitizers.23

Figure 5.

Mispredictions by the Toxtree and COEH models in the context of chemical similarity: Chemical similarity map for the discrete chemical data set and identification of mispredictions by Toxtree and the COEH model, respectively. Chemicals in the discrete data set are presented in clusters based on structural similarity. A structurally similar chemical was defined as having a Tanimoto distance of 0.80 or greater. Nodes in green are nonsensitizing chemicals, while nodes in red are sensitizing chemicals; these statuses were taken from the sensitization calls in the discrete chemical data set. The ellipses with the yellow border indicate a misprediction by the model. The yellow borders in Figure 5a identify mispredictions for Toxtree, while the yellow borders in Figure 5b identify the mispredictions for the COEH model (when characterizing the “borderline, may be hazardous” outcome from COEH as nonsensitizing).

Additionally, the Toxtree model predicted the outcomes of the chemicals in Cluster 1 better than the COEH model; in fact, Toxtree tended to perform better than the COEH model when there were at least 3 or more neighbors, as supported by an accuracy of 78% for Toxtree vs 59% for the COEH model (see Table 4). Conversely, the COEH model had better success than Toxtree when predicting chemicals with no other similar chemical in the data set −77% vs 68%, suggesting a modest improvement for chemicals not similar to well-studied clusters of known-sensitizers for the COEH model.

Table 4.

Model Accuracy by Number of Neighborsa

| accuracy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| number of neighbors | number of chemicals (n) | Toxtree | COEH (not conservative) |

| 0 | 139 | 68 | 77 |

| 1–3 | 80 | 73 | 78 |

| >3 | 32 | 78 | 59 |

The COEH model had a higher accuracy for chemicals with no neighbors in the data set, while Toxtree had a higher accuracy when there were more neighbors (i.e., greater than 3). This suggests that COEH has a broader coverage than Toxtree.

As previously mentioned, the molecular initiating event for a sensitization reaction—dermal or respiratory—is the covalent binding of a chemical to a protein, and this is the only information Toxtree makes use of for predicting sensitization potential. Interesting questions, therefore, are both how accurate any individual alert is, and whether the COEH model performed better or worse when presented with chemicals with a specific skin sensitization reactivity domain. Supplemental Figure 3 presents the distribution of skin sensitization reactivity alerts in the discrete chemical data set as identified by Toxtree. Some chemicals had more than one skin sensitization reactivity alert in their structure; all alerts for every chemical were included in the skin sensitization reactivity alerts distribution analysis.

When assessing model accuracy by skin sensitization reactivity alerts, Toxtree had relatively high accuracy for all alerts—the highest being Schiff base, which includes the isocyanates. On the other hand, SN2 alerts were especially prone to false positives. The COEH model (using the nonconservative approach) had lower accuracy for the SNAr (25%) and for the Michael acceptor (59%) alert. Overall, some alerts are likely more useful than others, and the COEH model had higher accuracy for chemicals with no alerts, indicating it can accurately identify sensitizers with no obvious protein binding mechanism (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distribution of accuracy across skin sensitization reactivity alerts.

116 chemicals had no alert, but, of those, 37 were true sensitizers according to the discrete chemical data set. Toxtree would, by design, mispredict these chemicals; however, the COEH model was still able to correctly classify many of them (n = 22) as sensitizers (Table 5).

Table 5.

Accuracy According to Skin Sensitization Reactivity Alerta

| skin sensitization reactivity alert | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNAr | Schiff base | Michael acceptor | acyl transfer agent | SN2 | no alert | |

| chemicals (n) | 8 | 49 | 33 | 56 | 29 | 116 |

| sensitizers (n) | 6 | 43 | 27 | 41 | 14 | 37 |

| non-sensitizers (n) | 2 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 79 |

| toxtree accuracy (%) | 75 | 88 | 82 | 73 | 48 | 68 |

| COEH (not conservative) accuracy (%) | 25 | 87 | 59 | 83 | 76 | 77 |

Accuracy of the models when broken down by skin sensitization reactivity alert. Toxtree had relatively high accuracy for all alerts except SN2, while the COEH model had relatively high accuracy for all alerts except SNAr and Michael acceptors. However, when no alerts were identified in a chemical, the COEH model was still able to identify true sensitizers (n = 22 out of 37) when Toxtree could not.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis indicates that while respiratory sensitization can be predicted with some accuracy by in silico models—and that agreement between the two models presented here provides a relatively confident prediction—there are some significant caveats. Despite overly general mechanistic assumptions by using Toxtree (i.e., a shared MIE between skin and respiratory sensitizers), Toxtree structural alerts clearly correctly identify many respiratory sensitizers; however, it is unclear to what extent this would be accurate in a real-world data set of unseen chemicals. The data set itself is likely biased toward chemicals with obvious sensitization mechanisms, as, in general, structural alerts tend to overpredict sensitization outcomes.54 Some alerts (e.g., SN2) are more prone to false positives than others, and Toxtree did not perform as well on chemicals with no similar chemical in the data set, indicating that it might do less well with novel chemistries or a broader, more diverse chemical space. On the other hand, the COEH model clearly adds some benefit both when used alone (in that it has a modestly higher accuracy) as well as in addition to Toxtree (correctly identifying some respiratory sensitizers in the group which lacked skin sensitization reactivity alerts), although in some specific skin sensitization reactivity alert categories it may be at a disadvantage to Toxtree. Regardless of methodology, to some extent, these data sets are gathered by focusing on respiratory sensitizers based on known mechanisms; consequently, the performance is likely overstated.55

Interestingly, the areas where the models agreed but incorrectly called the status point to some intriguing problems. For some chemicals (e.g., piperazine), both models classified it as a non-sensitizer, yet the ECHA dossier indicates that human exposure data has established respiratory sensitization, and there is a positive GPMT indicating skin sensitization potential56 —piperazine likely, therefore, has a sensitization mechanism that is simply poorly understood. On the other hand, diallyl phthalate was classified as a sensitizer by both models but was labeled as a non-sensitizer, despite a strong structural similarity to sensitizers, and the ECHA dossier57 indicates a positive LLNA test—it might, actually, be a sensitizer and simply misidentified if inhalation exposures are avoided because of other toxicity concerns. Lastly, some chemicals identified by the models as non-sensitizers but do have some evidence of sensitization, such as acetic acid, are in widespread use, and true IgE sensitization is likely rare, although given the high levels of exposure experienced by some occupations, some allergic responses are inevitable. It is likely that some of these chemicals would not be considered a respiratory sensitizer by GHS standards, and in this case, the call by the model might be the most relevant.

This points to two broader issues that remain challenges for the field going forward: one, sensitization is treated by most models (and indeed some regulatory approaches) as a binary status, but potency is key both for hazard identification and for accurate models—despite the relative ease of predicting two-class vs multiclass labels, most models will falter in distinguishing weak from non-sensitizers but will do well when distinguishing strong sensitizers from non-sensitizers.58 One step forward then would be an undertaking similar to Basketter et al.32 to identify potency in respiratory sensitization.

A second, and related, issue is data quality. Above and beyond the many issues typically present in chemical data sets (e.g., redundancy of the data sets, unclear chemical identifications, etc.), the data sets used in this analysis represent a variety of data quality issues59 and also highlight the major roadblock that is negative respiratory sensitization data; there simply is no perfect way to identify negative respiratory sensitizers. While an LLNA or human patch test can provide a skin sensitization status, a similar test does not currently exist for respiratory sensitization, and this lack of a gold standard complicates consistent data. Skin prick tests have been employed for diagnosis of clinical respiratory sensitization outcomes; however, this has almost universally been for high molecular weight (i.e., protein) allergy,60 as these tests have not been demonstrated to be useful in detecting chemical respiratory sensitization responses.61 Some quantitative measures of pulmonary function, such as “forced expiratory volume in 1 second” (FEV1), have been considered as potential metrics of human respiratory sensitization outcomes;5 however, these are traditionally utilized for high-molecular-weight sensitizers rather than chemical respiratory sensitizers. Overlap with other coexposures (e.g., smoking) or outcomes (e.g., COPD, emphysema, etc.) and physical irritation may also confound these measures. Further, although data for immunoglobulins may be available for high-molecular-weight allergens, such as proteins, the role of immunoglobulins in the clinical manifestation of chemical respiratory sensitization remains unclear,7 which diminishes the usefulness of these tests in the diagnosis of chemical respiratory allergy. Most of what is available for chemical respiratory sensitization is occupational observational data, but this too always has confounders. Indeed, since it is often the practice in industrial hygiene to identify the molecular etiology of occupational asthma based on suspicion of sensitization potential of the candidate exposures (one of the suggested uses of the COEH model), mapping out a more diverse and less redundant sample of the chemical universe of possible respiratory sensitizers and non-sensitizers is key for advancing the field.

In the absence of a validated animal model (and it is unlikely an animal model could recapitulate the totality of exposure scenarios that lead to occupational asthma), one way forward is to focus on a more data-driven capture of exposures (e.g., exposomics)62 and phenotypes and look for possible sensitizers in a more unsupervised manner—this would have the added benefit at looking for possible synergistic mixtures as well, since most occupational exposure scenarios involve multiple chemicals. Further, the development of additional in vitro models based on human cell lines or organ-on-a-chip models will improve our ability to understand the molecular mechanism of respiratory sensitization. In fact, the absence of an in vivo model could provide an opportunity to break away from the traditional validation paradigm of comparing in vitro methods to in vivo animal models, which conventionally carry the label of “gold standard” but may not always be the case.21 Additionally, the available data needs to be curated and organized in a more accessible way: the lack of clear and consistent terminology between toxicologists and the medical community, and the ambiguity of occupational asthma in terms of true sensitizers, makes assembling a high-standard data set quite difficult.

Nonetheless, our results indicate that both Toxtree and the COEH model are useful for a screening-level determination of respiratory sensitization potential, and the COEH model in particular is likely useful when trying to identify chemicals with no clear mechanism. Moreover, our data indicate that when combined, a consensus between the two models actually represents a high-confidence determination of respiratory sensitization status, and looking at instances where the models agree and disagree, or disagree with the literature, points the way to improving our understanding of respiratory sensitization. Specifically, we need to better understand the divergence of the AOP between respiratory and dermal sensitizers, and establish a gold-standard data set identifying chemicals that have both dermal sensitization status and respiratory sensitization status unambiguously established (both positives and negatives, and ideally with potency data) to further assess the usefulness of dermal sensitization status to characterize respiratory sensitization potential. Models require an accurate survey of the terrain before they can be fairly judged.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to Lori Rosman, M.L.S. (Lead Informationist, Johns Hopkins University) for her assistance with the literature search. The earlier support for Emily Golden by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Emily Golden was supported by unrestricted funds from the Grace Foundation and an NIEHS training grant (T32 ES007141).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00320.

Table 1: Scoping Search Strategy. Table 2: Data Sets. Table 3: Chemical Identifiers by Clusters in the Chemical Similarity Map. Table 4: Performance Metrics. Figure 1: Harmonized CLP Respiratory Sensitization Classification Chemical Category Distribution. Figure 2: Chemical Similarity Map for the Discrete Chemical Data Set with all Clusters Identified. Figure 3: Skin Sensitization Reactivity Alert Distribution. (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00320

Contributor Information

Emily Golden, Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, United States.

Mikhail Maertens, Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, United States.

Thomas Hartung, Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, United States; CAAT-Europe, University of Konstanz, 78464 Konstanz, Germany.

Alexandra Maertens, Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Balmes J, Becklake M, Blanc P, Henneberger P, Kreiss K, Mapp C, Milton D, Schwartz D, Toren K, and Viegi G (2003) Environmental, and Occupational Health Assembly, A. T. S. American Thoracic Society Statement: Occupational contribution to the burden of airway disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 167, 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Torén K, and Blanc PD (2009) Asthma caused by occupational exposures is common - a systematic analysis of estimates of the population-attributable fraction. BMC Pulm. Med 9, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Burge S, and Hoyle J (2012) Current topics in occupational asthma. Expert Rev. Respir. Med 6, 615–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Trivedi V, Apala DR, and Iyer VN (2017) Occupational asthma: diagnostic challenges and management dilemmas. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med 23, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Balmes JR (2013) Occupational Lung Diseases, In CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 5th ed. (LaDou J, and Harrison RJ, Eds.) McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wild LG, and Lopez M (2003) Occupational asthma caused by high-molecular-weight substances. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am 23, 235–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kimber I, Dearman RJ, Basketter DA, and Boverhof DR (2014) Chemical respiratory allergy: reverse engineering an adverse outcome pathway. Toxicology 318, 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kimber I, Agius R, Basketter DA, Corsini E, Cullinan P, Dearman RJ, Gimenez-Arnau E, Greenwell L, Hartung T, Kuper F, Maestrelli P, Roggen E, Rovida C, and European Centre for the Validation of Alternative, M. (2007) Chemical respiratory allergy: opportunities for hazard identification and characterisation. The report and recommendations of ECVAM workshop 60. ATLA, Altern. Lab. Anim 35, 243–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Arts JH, and Kuper CF (2007) Animal models to test respiratory allergy of low molecular weight chemicals: a guidance. Methods 41, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chary A, Hennen J, Klein SG, Serchi T, Gutleb AC, and Blömeke B (2018) Respiratory sensitization: toxicological point of view on the available assays. Arch. Toxicol 92, 803–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kimber I, Poole A, and Basketter DA (2018) Skin and respiratory chemical allergy: confluence and divergence in a hybrid adverse outcome pathway. Toxicol. Res 7, 586–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Anderson SE, Siegel PD, and Meade BJ (2011) The LLNA: A Brief Review of Recent Advances and Limitations. J. Allergy 2011, 424203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gordon S, Daneshian M, Bouwstra J, Caloni F, Constant S, Davies DE, Dandekar G, Guzman CA, Fabian E, Haltner E, Hartung T, Hasiwa N, Hayden P, Kandarova H, Khare S, Krug HF, Kneuer C, Leist M, Lian G, Marx U, Metzger M, Ott K, Prieto P, Roberts MS, Roggen EL, Tralau T, van den Braak C, Walles H, and Lehr CM (2015) Non-animal models of epithelial barriers (skin, intestine and lung) in research, industrial applications and regulatory toxicology. ALTEX 32, 327–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hoffmann S (2015) LLNA variability: An essential ingredient for a comprehensive assessment of non-animal skin sensitization test methods and strategies. Altex 32, 379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Luechtefeld T, Maertens A, Russo DP, Rovida C, Zhu H, and Hartung T (2016) Analysis of publically available skin sensitization data from REACH registrations 2008–2014. Altex 33, 135–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kimber I, Warbrick EV, and Dearman RJ (1998) Chemical respiratory allergy, IgE and the relevance of predictive test methods: a commentary. Hum. Exp. Toxicol 17, 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kimber I, and Dearman RJ (2002) Chemical respiratory allergy: role of IgE antibody and relevance of route of exposure. Toxicology 181–182, 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).National Research Council (NRC) (2007) Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hartung T (2008) Food for thought⋯ on animal tests. Altex 25, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hartung T (2009) Toxicology for the twenty-first century. Nature 460, 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Leist M, and Hartung T (2013) Inflammatory findings on species extrapolations: humans are definitely no 70-kg mice. Arch. Toxicol 87, 563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Alves VM, Capuzzi SJ, Muratov E, Braga RC, Thornton T, Fourches D, Strickland J, Kleinstreuer N, Andrade CH, and Tropsha A (2016) QSAR models of human data can enrich or replace LLNA testing for human skin sensitization. Green Chem. 18, 6501–6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rovida C, Martin SF, Vivier M, Weltzien HU, and Roggen E (2013) Advanced tests for skin and respiratory sensitization assessment. Altex 30, 231–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lehmann AD, Daum N, Bur M, Lehr C-M, Gehr P, and Rothen-Rutishauser BM (2011) An in vitro triple cell co-culture model with primary cells mimicking the human alveolar epithelial barrier. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 77, 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Mizoguchi I, Ohashi M, Chiba Y, Hasegawa H, Xu M, Owaki T, and Yoshimoto T (2017) Prediction of Chemical Respiratory and Contact Sensitizers by OX40L Expression in Dendritic Cells Using a Novel 3D Coculture System. Front. Immunol 8, 929–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Forreryd A, Johansson H, Albrekt AS, Borrebaeck CA, and Lindstedt M (2015) Prediction of chemical respiratory sensitizers using GARD, a novel in vitro assay based on a genomic biomarker signature. PLoS One 10, No. e0118808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lalko JF, Kimber I, Gerberick GF, Foertsch LM, Api AM, and Dearman RJ (2012) The direct peptide reactivity assay: selectivity of chemical respiratory allergens. Toxicol. Sci 129, 421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Dik S, Rorije E, Schwillens P, van Loveren H, and Ezendam J (2016) Can the Direct Peptide Reactivity Assay Be Used for the Identification of Respiratory Sensitization Potential of Chemicals? Toxicol. Sci 153, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Quirce S, and Sastre J (2019) Occupational asthma: clinical phenotypes, biomarkers, and management. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med 25, 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Sullivan KM, Enoch J, Ezendam J, Sewald K, Roggen EL, and Cochrane S (2017) An Adverse Outcome Pathway for Sensitization of the Respiratory Tract by Low-Molecular-Weight Chemicals: Building Evidence to Support the Utility of In Vitro and In Silico Methods in a Regulatory Context. Applied In Vitro Toxicology 3, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2012) The adverse outcome pathway for skin sensitisation initiated by covalent binding for proteins. Part 1: Scientific evidence Available: https://www.oecd.org/env/the-adverse-outcome-pathway-for-skin-sensitisation-initiated-by-covalent-binding-to-proteins-9789264221444-en.htm.

- (32).Basketter DA, Alépée N, Ashikaga T, Barroso J, Gilmour N, Goebel C, Hibatallah J, Hoffmann S, Kern P, Martinozzi-Teissier S, Maxwell G, Reisinger K, Sakaguchi H, Schepky A, Tailhardat M, and Templier M (2014) Categorization of chemicals according to their relative human skin sensitizing potency. Dermatitis 25, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Golden E, Macmillan DS, Dameron G, Kern P, Hartung T, and Maertens A (2020) Evaluation of the global performance of eight in silico skin sensitization models using human data. ALTEX, 1 DOI: 10.14573/altex.1911261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).North CM, Ezendam J, Hotchkiss JA, Maier C, Aoyama K, Enoch S, Goetz A, Graham C, Kimber I, Karjalainen A, Pauluhn J, Roggen EL, Selgrade M, Tarlo SM, and Chen CL (2016) Developing a framework for assessing chemical respiratory sensitization: A workshop report. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 80, 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Dik S, Ezendam J, Cunningham AR, Carrasquer CA, van Loveren H, and Rorije E (2014) Evaluation of In Silico Models for the Identification of Respiratory Sensitizers. Toxicol. Sci 142, 385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health. Chemical Asthma Hazard Assessment Program.

- (37).United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) (2010) TSCA New Chemicals Program (NCP) Chemical Categories. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-10/documents/ncp_chemical_categories_august_2010_version_0.pdf.

- (38).Laboratory of Mathematical Chemistry (LMC) (2020) OECD QSAR Toolbox 4.4.1

- (39).Idea Consult, Ltd. (2015) Toxtree 2.6.13

- (40).European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2020) C&L Inventory Database. Available: https://echa.europa.eu/information-on-chemicals/cl-inventory-database.

- (41).Wang Y, Xiao J, Suzek TO, Zhang J, Wang J, and Bryant SH (2009) PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W623–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, and Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Timeline of OSHA’s 40 Year History. Available: https://www.osha.gov/osha40/timeline.html.

- (44).Graham C, Rosenkranz HS, and Karol MH (1997) Structure-Activity Model of Chemicals That Cause Human Respiratory Sensitization. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 26, 296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Jarvis J, Seed MJ, Elton R, Sawyer L, and Agius R (2005) Relationship between chemical structure and the occupational asthma hazard of low molecular weight organic compounds. Occup. Environ. Med 62, 243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Enoch SJ, Seed MJ, Roberts DW, Cronin MTD, Stocks SJ, and Agius RM (2012) Development of Mechanism-Based Structural Alerts for Respiratory Sensitization Hazard Identification. Chem. Res. Toxicol 25, 2490–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Seed MJ, Enoch SJ, and Agius RM (2015) Chemical determinants of occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Occupational Medicine 65, 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Basketter DA, Wright ZM, Warbrick EV, Dearman RJ, Kimber I, Ryan CA, Gerberick GF, and White IR (2001) Human potency predictions for aldehydes using the local lymph node assay. Contact Dermatitis 45, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Patlewicz G, Basketter DA, Smith CK, Hotchkiss SAM, and Roberts DW (2001) Skin-sensitization structure-activity relationships for aldehydes. Contact Dermatitis 44, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wandall B, Hansson SO, and Rudén C (2007) Bias in toxicology. Arch. Toxicol 81, 605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Hoffmann S, de Vries RBM, Stephens ML, Beck NB, Dirven H, Fowle JR 3rd, Goodman JE, Hartung T, Kimber I, Lalu MM, Thayer K, Whaley P, Wikoff D, and Tsaioun K (2017) A primer on systematic reviews in toxicology. Arch. Toxicol 91, 2551–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Hartung T, Luechtefeld T, Maertens A, and Kleensang A (2013) Integrated testing strategies for safety assessments. Altex 30, 3–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2008) Guidance on information requirements and chemcial safety assessment: Chapter R.6: QSARs and grouping of chemicals Available: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13632/information_requirements_r6_en.pdf/77f49f81-b76d-40ab-8513-4f3a533b6ac9.

- (54).Alves V, Muratov E, Capuzzi S, Politi R, Low Y, Braga R, Zakharov AV, Sedykh A, Mokshyna E, Farag S, Andrade C, Kuz’min V, Fourches D, and Tropsha A (2016) Alarms about structural alerts. Green Chem. 18, 4348–4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Arts J (2020) How to assess respiratory sensitization of low molecular weight chemicals? Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 225, 113469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2020) Dossier for Piperazine (CASRN 110-85-0) - Sensitisation Endpoint. Available: https://echa.europa.eu/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/14941/7/5/1.

- (57).European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) (2020) Dossier for Diallyl phthalate (CASRN 131-17-9) - Sensitisation Endpoint. Available: https://echa.europa.eu/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/12746/7/5/1.

- (58).Luechtefeld T, Maertens A, McKim JM, Hartung T, Kleensang A, and Sá-Rocha V (2015) Probabilistic hazard assessment for skin sensitization potency by dose-response modeling using feature elimination instead of quantitative structure-activity relationships. J. Appl. Toxicol 35, 1361–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Luechtefeld T, and Hartung T (2017) Computational approaches to chemical hazard assessment. ALTEX 34, 459–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Vandenplas O, Suojalehto H, and Cullinan P (2017) Diagnosing occupational asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 47, 6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Cochrane SA, Arts JHE, Ehnes C, Hindle S, Hollnagel HM, Poole A, Suto H, and Kimber I (2015) Thresholds in chemical respiratory sensitisation. Toxicology 333, 179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sille FCM, Karakitsios S, Kleensang A, Koehler K, Maertens A, Miller GW, Prasse C, Quiros-Alcala L, Ramachandran G, Rappaport SM, Rule AM, Sarigiannis D, Smirnova L, and Hartung T (2020) The exposome - a new approach for risk assessment. ALTEX 37, 3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.