Abstract

Background:

Chronic urticaria is a heterogenous skin disorder representing one of the important reasons for consultation with a dermatologist. Dermatology post-graduate students play an importanrt role in the treatment of patients with chronic urticaria.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to describe clinical characteristics of patients with chronic urticaria and assess adherence to the guidelines by postgraduate students in the department of dermatology of a tertiary care center.

Materials and Methods:

In this retrospective study, prescriptions of patients with chronic urticaria and/or angioedema presenting to the outpatient department for 5 months were analyzed. Percentage of prescriptions adhering to international urticaria management guidelines was calculated. Urticaria Activity Score, percentage of patients receiving second-generation antihistamines, first-generation antihistamines, and other drugs was recorded. Comorbidities in patients with chronic urticaria were also noted.

Results:

A total of 60 patients (mean age 32.1 years; 58.3% male) were included in. Mean (SD) duration of urticaria at the time of study was 4.7 (2.7) months. Demographism and history of allergy to drugs was present in 45 (75%) and 4 (6.7%) patients. Mean (SD) Urticaria Activity Score was 12.5 (6.5). A total of 12 (20%) patients had comorbidities. Mean number of drugs received per patient was 1.7 (0.5). A total of 47 (78.3%) patients received second-generation antihistamines, whereas 11 (18.3%) received first-generation antihistamines. Two (3.3%) patients received combination of first-generation and second-generation antihistamines. Fexofenadine, levocetirizine, bilastine, and cetirizine was prescribed to 24 (40%), 26 (43.3%), 18 (30%), and 14 (23.3%) patients. There was no significant difference in male and female patients receiving fexofenadine (P = 0.59) or levocetirizine (P = 0.13).

Conclusion:

Adherence to urticaria management guidelines by resident doctors in dermatology department in our institute was satisfactory.

KEY WORDS: Antihistamine, first-line therapy, steroids, urticaria guideline

Introduction

Chronic urticaria is a heterogeneous group of skin diseases associated with wheal and flares present for more than 6 weeks. Globally, about 1% of the population is estimated to have chronic urticaria. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in Asia has an increasing trend. The disease may or may not be associated with angioedema. Chronic urticaria can significantly affect the quality of life of the patients suffering from it. Chronic urticaria is broadly classified into two types are as follows: chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria. In chronic spontaneous urticarial, symptoms occur without specific identifiable triggers. In chronic inducible urticaria, symptoms are induced by different triggers including cold, heat, pressure, dermographism, vibration, cholinergic stimulus, or contact.[1]

Antihistamines represent the most important class and are used for the primary treatment of chronic urtcaria. Antihistamines are classified into first-generation and second-generation agents. Examples of first-generation drugs include chlorpheniramine maleate, hydroxyzine, etc. Second-generation antihistamines include fexofenadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, desloratadine, rupatadaine, bilastine, etc. First-generation drugs cross blood–brain barrier, and hence result in sedation. These drugs also cause impairment of psychomotor performance. In higher doses, they cause result in life threatening complications.

Considering the advantages of second-generation antihistamines over first-generation agents, guidelines recommend use of second-generation antihistamines as first-line therapy. In patients not responding to standard dose of second-generation nonsedating antihistamines, up dosing up to 4-fold is recommended by the guidelines.[2,3,4]

Adherence to best practice guidelines in chronic urticaria improves patient's outcomes.[5] Physician's age, clinical experience, and specialty are some of the important factors that influence adherence to the urticaria guidelines. Other factors include regional features such as the availability of medicines for the management of urticaria and country specifics.[6] A study reported that nonexperts still prescribe large amounts of sedating antihistamines. This might have a negative impact on urticaria control and patient satisfaction.[7] Another study showed poor knowledge of guideline recommendations in physicians treating urticaria patients in Ecuador.[8]

According to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating adherence of postgraduate students to guidelines for urticaria management.

Objective

The objective of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of patients with chronic urticaria and assess adherence to the guidelines by postgraduate students in the department of dermatology of a tertiary care center.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, we reviewed prescriptions of patients with chronic urticaria and/or angioedema presenting to the outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital. Patients presenting to the department for 5 months (October 2020 to February 2021) were included. Patients with urticarial vasculitis were excluded from this analysis. Percentage of prescriptions adhering to international urticaria management guidelines was calculated. Other evaluation parameters included severity of urticaria as estimated by Urticaria Activity Score, percentage of patients receiving second-generation antihistamines, first-generation antihistamines, and other drugs. Comorbidities in patients with chronic urticaria were also recorded. Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee was obtained.

Statistical analysis

Collected data were entered into the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for analysis. Categorical data are presented as frequency and percentages, whereas continuous data are presented as mean and SD. Unpaired t test was used for comparison of continuous variables in two groups. Chi-square test was used for the comparison of numerical data between two groups. A P value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 60 patients with chronic urticaria were included in this study. The mean (SD) age of patients was 32.1 (11.1) years. A total of 35 (58.3%) male patients and 25 (41.7%) female patients were included in the study. There was no significant difference in the mean (SD) age of male and female patients [32.7 (10.8) vs. 31.4 (11.8); P = 0.66].

The mean (SD) duration of urticaria at the time of study was 4.7 (2.7) months [Table 1]. No significant difference in mean (SD) duration of urticaria was observed between male and female patients [4.9 (2.9) vs. 4.4 (2.4) months; P = 0.45].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Parameter | Results |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age in years | 32.1 (11.1) |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Male | 35 (58.3%) |

| Female | 25 (41.7%) |

| Mean (SD) duration of chronic urticaria in months | 4.7 (2.7) |

| History of allergy to drugs n (%) | 4 (6.7%) |

| Angioedema n (%) | 23 (38.3%) |

| Dermographism n (%) | 45 (75%) |

| UAS7 score mean (SD) | 12.5 (6.5) |

Dermographism was present in 45 (75%) patients. Of 35 male patients, dermographism was present in 28 (80%) patients, whereas of 25 female patients 17 (68%) had dermographism. The difference in number of male and female patients for presence of dermographism was not significant (P = 0.29). A total of four (6.7%) patients had history of allergy to some drugs. Of four patients, two had history of allergy to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and 1 patient had allergy to sulpha drugs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors each. The mean (SD) Urticaria Activity Score was 12.5 (6.5).

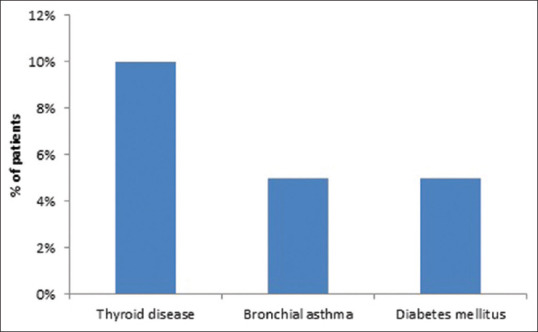

A total of 12 (20%) patients had comorbidities. Thyroid disease was present in 6 (10%) patients, whereas bronchial asthma and diabetes mellitus were present in 3 (5%) patients each [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Comorbidities in patients with chronic urticaria

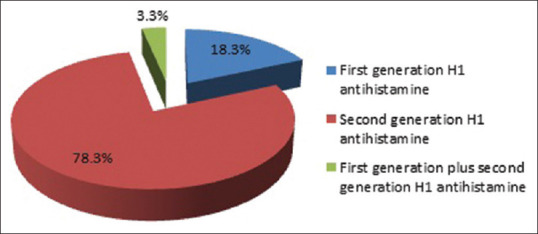

Mean number of drugs received per patient was 1.7 (0.5). A total of 47 (78.3%) patients received second-generation antihistamines, whereas 11 (18.3%) received first-generation antihistamines. Two (3.3%) patients received a combination of first-generation and second-generation antihistamines [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Prescriptions of first-generation and second-generation antihistamines

Fexofenadine, levocetirizine, bilastine, and cetirizine was prescribed to 24 (40%), 26 (43.3%), 18 (30%), and 14 (23.3%) patients. There was no significant difference in male and female patients receiving fexofenadine (P = 0.59) or levocetirizine (P = 0.13). Percentages of patients receiving other medicines are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prescriptions of antihistamines and other drugs in patients with chronic urticaria

| Name of drug | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fexofenadine | 24 (40%) |

| Levocetirizine | 26 (43.3%) |

| Cetirizine | 14 (23.3%) |

| Loratadine | 1 (1.7%) |

| Bilastine | 18 (30%) |

| Desloratadine | 6 (10%) |

| Hydroxyzine | 7 (11.7%) |

| Chlorpheniramine maleate | 5 (8.3%) |

| Prednisolone | 1 (1.7%) |

| Cyclosporine | 1 (1.7%) |

Discussion

Chronic urticaria is a common dermatological condition seen in clinical practice. In this study, we examined the adherence to urticaria management guidelines by the resident doctors in a tertiary care hospital. In our study, the number of male patients was more than female patients. Our observation is in contrast with the literature which suggests predominance of female population in chronic urticaria.[9] In another study (n = 48) from Mumbai, India, there was slightly more number of male (52.1%) than female population (47.9%).[10] Similar observation was seen in another study from Mumbai in which fexofenadine was used in higher than normal doses in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria.[11] These differences may be due to small sample sizes in the studies. Larger multicenter epidemiologic studies are not available to exactly determine gender-wise differences in patients with urticaria.

Symptomatic dermographism has been reported as the most common type of inducible urticaria affecting 24.8% of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria.[12] In our study, dermographism was observed in three-fourth of patients without gender-wise difference in its prevalence. We did not specifically categorize patients into chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria.

Medications may be responsible for causing or triggering urticaria. The commonly implicated drugs include aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.[13] Our observations are in accordance with this. Of 6.7% of patients with a reported history of allergy to medications, two had an allergy to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, whereas 1 patient each had allergy to sulpha drugs and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. It has been reported that about 40–50% patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria also have angioedema.[14] In our study, angioedema was present in 28.3% patients. Autoimmune thyroid disease is known to be among common comorbidities in patients with chronic urticaria.[15] In our study, 10% patients had thyroid disease.

Guidelines and consensus statements recommend second-generation nonsedating antihistamines as first-line treatment for patients with chronic urticaria.[2,3,4] In our study, 78.3% patients received second-generation antihistamines, suggesting satisfactory adherence to the these recommendations. First-generation antihistamines were prescribed to 18.3% patients. Only two patients received combination of first-generation and second-generation antihistamines.

According to a Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials, no single H1-antihistamine is recognized as the most effective.[16]

Several factors including patient type, needs of patients, and patient characteristics are considered while selecting the choice of treatment.[17]

In our study, several antihistamines were prescribed to patients with chronic urticaria among which levocetirizine, fexofenadine, and bilastine were the three most commonly used second-generation antihistamines. Bilastine and fexofenadine are classified as brain nonpenetrating antihistamines.[18]

First-generation antihistamines are associated with several adverse effects including sedation, drowsiness, impairment of psychomotor function, delay and reduction in rapid eye moment sleep and reduction in work efficiency.[19] Despite the known adverse events, among the first-generation, hydroxyzine and chlorpheniramine were prescribed to few patients in our study. Only two patients received treatment other than antihistamines.

Mean number of drugs received per patient was 1.7. This may be explained by the setting in which the study was performed. Being a tertiary care center, many patients visit the dermatology department after visiting primary care physician. Hence, more than one drugs are often needed for these patients.

Overall, our study provides significant insights into the clinical presentation, associated factors, and treatment pattern of patients with chronic urticaria during their first visit to a teaching hospital. However, our study is associated with some limitations. It was a single-center cross-sectional study involving small sample size. Larger longitudinal multicenter studies are required to confirm our observations.

Conclusion

Antihistamines represent an important treatment option for patients with chronic urticaria. All patients in our study received treatment with an antihistamine. Second-generation antihistamines are recommended as first-line treatment for chronic urticaria. In our study, majority of the patients received second-generation antihistamines. Overall, adherence to urticaria management guidelines by resident doctors in dermatology department in our institute was satisfactory. Larger and long-term studies are required to confirm our observations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chu C-Y, Al Hammadi A, Agmon-Levin N, Atakan N, Farag A, Arnaout RK, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of chronic spontaneous urticaria in patients refractory to H1-Antihistamines in Asia, Middle-East and Africa: Results from the AWARE-AMAC study. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13:100117. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Jensen CB, Canonica GW, Church MK, Gimnez-Arnau AM, et al. EAACI/GA2 LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: Management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Abdul Latiff AH, Baker D, Ballmer-Weber B, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73:1393–414. doi: 10.1111/all.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godse K, De A, Zawar V, Shah B, Girdhar M, Rajagopalan M, et al. Consensus statement for the diagnosis and treatment of urticaria: A 2017 update. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:2–15. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_308_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlon NP, Edgar JDM. Adherence to best practice guidelines in Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) improves patient outcome. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:28506. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolkhir P, Pogorelov D, Darlenski R, Caminati M, Tanno LK, Pham DL, et al. Management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: A worldwide perspective. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11:14. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrer M, Jauregui I, Bartra J, Davila I, del Cuvillo A, Montoro J. Chronic urticaria: Do urticaria nonexperts implement treatment guidelines? A survey of adherence to published guidelines by nonexperts. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:823–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherrez A, Maurer M, Weller K, Calderon JC, Simancas-Recines D, Ojeda IC. Knowledge and management of chronic spontaneous urticaria in Latin America: A cross-sectional study in Ecuador. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s40413-017-0150-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassano N, Colombo D, Bellia G, Zagni E, Vena GA. Gender-related differences in chronic urticaria. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151:544–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pherwani AV, Bansode G, Gadhia S. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:110–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.94277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godse KV, Nadkarni NJ, Jani G, Ghate S. Fexofenadine in higher doses in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2010;1:45–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.73262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez J, Amaya E, Acevedo A, Celis A, Caraballo D, Cardona R. Prevalence of inducible urticaria in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: Associated risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachdeva S, Gupta V, Amin SS, Tahseen M. Chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:622–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez-Borges M, Asero R, Ansotegui IJ, Baiardini I, Bernstein JA, Canonica GW, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of urticaria and angioedema: A worldwide perspective. World Allergy Open J. 2012;5:125–47. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182758d6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Najafipour M, Zareizadeh M, Najafipour F. Relationship between Chronic urticaria and autoimmune thyroid disease. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2018;9:158–61. doi: 10.4103/japtr.JAPTR_342_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma M, Bennett C, Cohen SN, Carter B. H1-antihistamines for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD006137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006137.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baharudin A, Abdul Latiff A-H, Woo K, Yap Felix B-B, Tang IP, Leong KF, et al. Using patient profiles to guide the choice of antihistamines in the primary care setting in Malaysia: Expert consensus and recommendations. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:1267–75. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S221059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawauchi H, Yanai K, Wang D-Y, Itahashi K, Okubo K. Antihistamines for allergic rhinitis treatment from the viewpoint of nonsedative properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:213. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Church MK, Maurer M, Simons FER, Bindslev-Jensen C, van Cauwenberge P, Bousquet J, et al. Risk of first-generation H(1)-antihistamines: A GA(2)LEN position paper. Allergy. 2010;65:459–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]