Introduction

The neem tree is commonly used as a traditional panacea for skin ailments in India. For thousands of years, the neem tree has been used as a shield against both agricultural pests and cutaneous infections or infestations.[1] The persistent popularity of neem in skin, hair, and dental care is reflected in the wide range of neem-based personal care products [Figure 1] in the Indian market. Indian dermatologists face neem in diverse situations: from neonates placed on a bed of neem leaves to octogenarians who rely on neem chew-sticks for oral hygiene. The traditional uses of neem are being re-explored. Commercial neem formulations are being used as an alternative to synthetic pesticides in several countries.[2] A foreign patent on the antifungal properties of neem sparked India's landmark “biopiracy” battle.[3,4] We briefly review the relevance of the neem tree in Indian dermatology practice.

Figure 1.

Neem products in the Indian market

The Tree and Its Chemistry

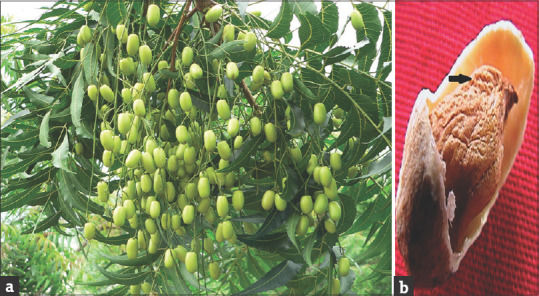

The neem tree (Azadirachta indica) or the Indian lilac belongs to the family Meliaceae and genus Azadirachta. It is widely distributed in the arid areas of several tropical and subtropical countries. It usually grows to a height of 15–20 m and has pinnate leaves (20–40 cm long), asymmetric leaflets (3–8 cm long), and white fragrant flowers. The fruits are round to oval, yellowish green to yellow, olive-like drupes [Figure 2a].[5]

Figure 2.

(a) Neem fruits amidst neem leaves. (b) Neem kernel (rich in limonoids)

Neem has abundant, complex, and diverse phytochemicals. More than 400 phytochemicals have been identified. It contains isoprenoids (diterpenoids and triterpenoids) and non-isoprenoids [Table 1].[6,7,8,9] Neem is a rich source of a group of phytochemicals known as tetranortriterpenoids (limonoids). Limonoids (named after limonin, the first bitter tetranortripenoid isolated from citrus fruits) are responsible for the bitter taste of neem.[6] Limonoids contain 4,4,8-trimethyl-17-furanylsteroidal skeleton, which can be substituted with other functional groups.[8] Mature seed kernels [Figure 2b] and the initial stages of the pericarp contain the highest limonoid content.[9]

Table 1.

| Isoprenoids | Non-isoprenoids |

|---|---|

| Diterpenoids (margolone, margolonone, isomargonolone) | Carbohydrates |

| Triterpenoids | Proteins |

| Protolimonoids | Sulphur compounds |

| Mononortripenoids | Phenolics |

| Dinortripenoids | Flavonoids (rutin, quercitin, kaempferol, |

| Trinortripenoids | isorhamnetin, myricetin, and nimbaflavone) |

| Tetranortripenoid or limonoids (azadirone, azadiradione, epoxyazadiradione, 17β hydroxyazadiradione , gedunin, 7-deacetylgedunin, azadirachtin, salannin, nimbin, nimbidin, nimolicinol, vilasinin, vepinin, mahmoodin, nimbolide). | Flavonoglycosides |

| Coumarins | |

| Dihydrochalcone | |

| Tannins (gallocatechin, epicatechin, catechin, and epigallocatechin). | |

| Pentanortripenoids | Hydrocarbons |

| Hexanortripenoids | Acids (oxalic acid, ascorbic acid) |

| Octanortripenoids | Fatty acids and their derivatives (glycerides and methyl esters of oleic, stearic, palmitic and linoleic, arachidic, behenic, lignoceric, and myristic acids) |

| Nanonortripenoids | |

| Sesquiterpenoids | |

| Sterols |

*Examples listed in brackets

Tradition

Neem is mentioned in ancient Ayurvedic texts (1500 BCE–400 BCE). Its sanskrit name 'nimba' refers to its ability to bestow health.[10] In the African Kiswahili language, the neem tree is known as 'mwarubaini' or 40 cures as it is believed to cure 40 diseases.[11] It holds an important place in Indian festivals, epics, and folklore. A combination of bitter neem flowers or young neem leaves and sweet jaggery (representing the bittersweet nature of life) is consumed on the Hindu new year in some Indian states. Neem and turmeric are integral to the Mariamman temple festival in Tamil Nadu. The combination is believed to offer protection from diseases such as chicken pox, small pox, measles, and cholera.[10,12]

The neem tree is often referred to as 'the village pharmacy' in India. The bark, wood, sap, leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, and oil of the neem tree are used for varied medicinal purposes. Neem is incorporated into several polyherbal Ayurvedic preparations. Siddha, Unani-Tibb, and Homeopathy practitioners also use neem. Tender neem leaves were incorporated in the diet to reduce skin diseases. Infants are often given neem oil to prevent disease.[13] Mechanically extracted oil obtained from neem seed kernels is dark, bitter, and has a garlicky pungent smell due to sulphur compounds.[11]

Although there is no evidence of efficacy, neem is extensively used for medicinal purposes in India. Neem was used as a primitive antiseptic agent. Neonates are placed on a bed of neem leaves. Patients with chicken pox are also placed on a bed of neem leaves and bathed in neem water (personal observation). Neem branches are hung in the house during illness and outside labor rooms. Neem leaves were heated and tied on limbs prior to removing guinea worms. A decoction made of neem leaves is used for douching the vagina post-delivery. Neem twigs are chewed on to form a fibrous brush that maintains oral hygiene. Neem leaf paste or oil is used for acne, eczema, impetigo, ulcers, pustules, snake and scorpion bites, chicken pox, measles, scaly scalp, psoriasis, pruritus, dermatophytosis, leprosy, pediculosis, and scabies [Figure 3a–e]. Neem leaves are burnt as a protection from insects. The neem tree is also used for abdominal pain, spermatorrhea, leucorrhea, dysmenorrhea, fever, intestinal worms, joint pains, constipation, and hemorrhoids.[10,13,14,15,16]

Figure 3.

(a) Neem leaf paste applied on the erosions of pemphigus. (b) Neem leaf paste and brick powder applied on impetigo. (c) Neem leaf paste applied on psoriasis. (d) Neem leaf paste applied on herpes zoster. (e) Neem leaf paste applied on eczema

Neem is traditionally used as a pesticide and fertilizer in agriculture.[2] Dried neem leaves are placed in stored grains and cereals to ward off insects. Neem is also used to treat cattle wounds and infestations.[13]

Tradition to Science

Agriculture

A report describing the sparing of neem trees in a locust swarm increased the global research on neem.[4] Neem, at varying concentrations, has shown activity against more than 400 insects. It acts through multiple complex mechanisms, which include insect repellent, disrupting moulting, antifeedant, oviposition deterrence, inhibition of growth, mating disruption, and chemo-sterilization. It acts slowly unlike the quick knockdown effect of synthetic pesticides. It is a re-emerging broad spectrum biopesticide. It also acts on some fungi and nematodes. Commercial pesticides have azadirachtin (from neem seed kernels) as the main active ingredient. The multiple compounds and the multiple modes of action make the risk of resistance lower. It is also being used for the control of ectoparasites in animal husbandry.[2,11]

Dermatology

Several traditional medicinal uses of neem are congruous with in vitro or animal studies. The potential uses of neem in dermatology are summarized in [Table 2].[7,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] However, the scarcity of human trials has obscured its role in modern medicine.

Table 2.

Neem in dermatology: Potential areas for further research[7,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]

| Onychotillomania (due to bitter taste) |

| Insect repellent, myiasis*, pediculocidal, scabicidal**, tungiasis*** |

| Antifungal (eg. dermatophytes, Candida albicans, Aspergillus spp.), antibacterial, antiviral (eg. herpes simplex virus-1 and coxsackie B4 virus), antimalarial, antileishmanial (Leishmania donovani) |

| Immunomodulatory |

| Wound-healing |

| Psoriasis |

| Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesic, antipyretic, antiarthritic, antifibrotic |

| Anti-cancer |

| Melanogenesis inhibiting activity, protection against UV-B damage |

| Anti-androgenic, antifertility, spermicidial |

*A combination of neem and Hypericum perforatum oil in myiasis of domestic animals. **A combination of neem and turmeric was used in scabies. ***A combination of neem oil and coconut oil was used in tungiasis

Neem may be beneficial in cutaneous infections and wound healing. Nimbolide and neem leaf extract have demonstrated inhibitory effects on biofilms of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively.[34,35] Incorporation of neem leaf extract into calcium alginate fibers increased its antimicrobial activity.[36] Neem extract gel has been reported to be effective in reducing peridontopathic bacteria and improve chronic periodontitis.[17] A combination of neem and Hypericum perforatum oil was reported to be useful in ulcers, burns, and acute radiodermatitis.[37,38,39]

Neem may be beneficial in arthropod-related dermatoses. It is being explored in the control of malaria and African trympanosomiasis. Neem seed extract has been reported to reduce response to human odors, have an antifeedant effect, and reduce the longevity of Anopheles coluzzii.[40] However, 20% neem oil was shown to be less effective and provide a shorter duration of protection compared to DEET (N, N-diethyl-1, 3- methylbenzamide).[41] Azadirachtin and saponins are the repellent compounds. Due to insufficient evidence, it is not recommended for disease protection. It may provide some protection against nuisance bites.[19] Thus, the spectrum of susceptible arthropods, the active ingredients in neem and their effective concentrations, need to be explored further.

Neem limonoids such as azadirachtin, gedunin, and nimbolide target multiple pathways in cancer by anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic effects, and inhibition of tumor invasion.[42] A methanolic neem leaf extract was found to have antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and pro-apoptotic effects via modulation of the NF-kB pathway. Quercetin, a flavonoid phenolic compound, had the highest inhibitory effect on the TNF-α induced activation of NF-kB pathway.[43] Neem was reported to be useful in psoriasis in a study on 50 patients. Forty-four patients completed the study. Oral neem capsules (aqueous neem leaf extract) combined with topical crude tar (5%) and salicylic acid (3%) in petrolatum showed significant reduction in PASI in comparison to a combination of placebo and the same tar and salicylic acid ointment. No adverse effects were reported.[30] However, the lack of rigorous controlled trials precludes its use. Gallic acid, epicatechin, and catechin from the bark have antioxidant activity. The antioxidant effects may depend on the total phenol content.[43] Nimbolide had antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects in a murine model of bleomycin-induced scleroderma.[22] Nimbidin had anti-inflammatory and antiarthritic effects in rats.[26]

The limonoids azadiradione and gedunin can inhibit human pancreatic amylase and may be useful in postprandial hyperglycemia.[8] In addition, neem compounds have been reported to have anti-gastric ulcer, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, nephroprotective, neuroprotective, or anxiolytic properties.[7,14]

Adverse effects

Neem oil ingestion has resulted in the death of several children. A few cases of toxic encephalopathy and a case of toxic optic neuropathy has been reported in adults. Neem oil ingestion can cause vomiting, drowsiness, diarrhea, seizures, metabolic acidosis, altered sensorium, Reye-like syndrome, nephrotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity.[44,45,46] Neem and Morinda coreia leaves were reported as a possible cause of pseudotumor cerbri in a nine-month-old infant.[47] Neem was also reported as a possible cause of hemolytic anemia in a 35-year-old man with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.[48] Neem leaf poisoning has been implicated in ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest. It may cause hypoglycemia, and has to be used with caution in patients on anti-hyperglycemic agents. Neem leaf or oil ingestion is contraindicated in pregnancy, lactation, and children under 12 years.[16] The long-term effects of neem is also not clear. Contamination with fungal flora, aflatoxins and other compounds may also play a role in the toxicity of neem-based home remedies.[13]

There have been some reports of allergic contact dermatitis to neem oil. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis has been reported with the use of neem oil insect repellent in the garden.[49,50] Allergic contact stomatitis has been reported after the ingestion of neem leaves.[51] Jadhav reported a case series of lip leukoderma secondary to the use of neem twigs for oral hygiene. Three of the seven patients developed delayed depigmentation when patch tested with powdered neem leaves and neem twig scrapings.[52] Plant phenols and catechols may competitively inhibit tyrosinase and produce melanocytotoxicity in some predisposed individuals.[53] However, the exact compounds and the mechanisms of cutaneous adverse effects remain unclear.

Challenges posed by neem in modern dermatology

Neem contains complex multifunctional compounds, which can have variable stability and penetration.[16] Neem extracts are being incorporated into several skin and personal care products. However, the ingredient labels often mention the vague term “neem extract.” The active ingredients and their concentration can vary based on genetic variability, the part of tree used, growing, storage, and processing conditions.[54] The method of extraction (such as acetone, aqueous, methanolic, ethanolic, chloroform, acetonitrile extracts) is important as each method gives different compounds with different concentrations.[55] The widespread use of refined neem preparations, which are based on a small number of compounds, might induce resistance. Research on neem is still largely based on in vitro or animal models. Other challenges include toxicity, contamination, regulation, and low commercial interest (knowledge in the public domain cannot be patented).[13]

Although there are several challenges, newer technologies are improving the outlook towards natural products. Metabolomics can provide accurate data on the metabolites in natural products. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (often in combination with liquid chromatography) provide comprehensive metabolic profiles. Dereplication is done to exclude known compounds.[56] Regulatory guidelines have been developed for heterogenous mixtures from natural products.[57,58] Although several natural products can affect the microbiome, research on such interactions is still in its infancy.[56]

Conclusions

Although the neem tree is an important ethnomedicinal tree in India, it is still uncharted and untapped by modern dermatologists. The widespread use of neem and reports of toxicity warrant further research into both the traditional uses and safety profile of neem. The neem tree may offer intriguing prospects in the management of infections, wounds, pigmentation, inflammation, and arthropod-related dermatoses. It is imperative that we begin to explore and understand this bitter tree a little better.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr Gopinathan MC for the photographs of the neem tree, and his help in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Rangiah K, Gowda M. Method to quantify plant secondary metabolites: Quantification of neem metabolites from leaf, bark, and seed extracts as an example. In: Gowda M, Sheetal A, Kole C, editors. The Neem Genome. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaul O. Neem: A global perspective. In: Koul O, Wahab S, editors. Neem: Today and in the New Millennium. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheridan C. EPO neem patent revocation revives biopiracy debate. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:511–2. doi: 10.1038/nbt0505-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marden E. The neem tree patent: International conflict over the commodification of life. BC Int'l & Comp L Rev. 1999;22:279–95. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmutterer H. The tree and its characteristics. In: Schmutterer H, editor. The Neem Tree, Source of Unique Natural Products for Integrated Pest Management, Medicine, Industry and other Purposes. Weinheim: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 1995. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhila A, Rani K. Chemistry of the neem tree (Azadirachta indica A. Juss.) Fortschr Chem Org Naturst. 1999;78:47–149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6394-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kharwar RN, Sharma VK, Mishra A, Kumar J, Singh DK, Verma SK, et al. Harnessing the phytotherapeutic treasure troves of the ancient medicinal plant Azadirachta indica (Neem) and associated endophytic microorganisms. Planta Med. 2020;86:906–40. doi: 10.1055/a-1107-9370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponnusamy S, Haldar S, Mulani F, Zinjarde S, Thulasiram H, RaviKumar A. Gedunin and Azadiradione: Human pancreatic alpha-amylase inhibiting limonoids from Neem (Azadirachta indica) as anti-diabetic agents. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandreka A, Dandekar DS, Haldar S, Uttara V, Vijayshree SG, Mulani FA, et al. Triterpenoid profiling and functional characterization of the initial genes involved in isoprenoid biosynthesis in neem (Azadirachta indica) BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:214. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair SNV, Shilpa N, Varghese T, Tabassum IF. Neem: Traditional knowledge from Ayurveda. In: Gowda M, Sheetal A, Kole C, editors. The Neem Genome. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Research Council (US) Panel on Neem. Neem: A Tree for Solving Global Problems. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1992. PMID: 25121266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashalatha KL, Gowda M. Heritage of neem-peepal tree resides a profound scientific facts. In: Gowda M, Sheetal A, Kole C, editors. The Neem Genome. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 13–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puri HS. Neem. In: Hardman R, editor. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants—Industrial Profiles. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleem S, Muhammad G, Hussain MA, Bukhari SNA. A comprehensive review of phytochemical profile, bioactives for pharmaceuticals, and pharmacological attributes of Azadirachta indica. Phytother Res. 2018;32:1241–72. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul R, Prasad M, Sah NK. Anticancer biology of Azadirachta indica L (neem): A mini review. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:467–76. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.6.16850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO (World Health Organization) Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants. Vol. 3. Geneva: 2007. pp. 88–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhingra K, Vandana KL. Effectiveness of Azadirachta indica (neem) mouthrinse in plaque and gingivitis control: A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2017;15:4–15. doi: 10.1111/idh.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boeke SJ, Boersma MG, Alink GM, van Loon JJ, van Huis A, Dicke M, et al. Safety evaluation of neem (Azadirachta indica) derived pesticides. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94:25–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maia MF, Moore SJ. Plant-based insect repellents: A review of their efficacy, development and testing. Malar J. 2011;10(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khillare B, Shrivastav TG. Spermicidal activity of Azadirachta indica (neem) leaf extract. Contraception. 2003;68:225–9. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Ghaffar F, Semmler M. Efficacy of neem seed extract shampoo on head lice of naturally infected humans in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2007;100:329–32. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diddi S, Bale S, Pulivendala G, Godugu C. Nimbolide ameliorates fibrosis and inflammation in experimental murine model of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27:139–49. doi: 10.1007/s10787-018-0527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dayakar A, Chandrasekaran S, Veronica J, Sundar S, Maurya R. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of anti-leishmanial and immunomodulatory activity of Neem leaf extract in Leishmania donovani infection. Exp Parasitol. 2015;153:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akihisa T, Takahashi A, Kikuchi T, Takagi M, Watanabe K, Fukatsu M, et al. The melanogenesis-inhibitory, anti-inflammatory, and chemopreventive effects of limonoids in n-hexane extract of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (neem) seeds. J Oleo Sci. 2011;60:53–9. doi: 10.5650/jos.60.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngo HT, Hwang E, Seo SA, Park B, Sun ZW, Zhang M, et al. Topical application of neem leaves prevents wrinkles formation in UVB-exposed hairless mice. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2017;169:161–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur G, Sarwar Alam M, Athar M. Nimbidin suppresses functions of macrophages and neutrophils: Relevance to its antiinflammatory mechanisms. Phytother Res. 2004;18:419–24. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieder EA, Tosti A. Onychotillomania: An underrecognized disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natarajan V, Venugopal PV, Menon T. Effect of Azadirachta indica (neem) on the growth pattern of dermatophytes. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2003;21:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carnevali F, Franchini D, Otranto D, Giangaspero A, Di Bello A, Ciccarelli S, et al. A formulation of neem and hypericum oily extract for the treatment of the wound myiasis by Wohlfahrtia magnifica in domestic animals. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:2361–7. doi: 10.1007/s00436-019-06375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey SS, Jha AK, Kaur V. Aqueous extract of neem leaves in treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1994;60:63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles V, Charles SX. The use and efficacy of Azadirachta indica ADR ('Neem') and Curcuma longa ('Turmeric') in scabies. A pilot study. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:178–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghorbanian M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M, Allameh A, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Qorbani M. Study on the effect of neem (Azadirachta indica A.juss) leaf extract on the growth of Aspergillus parasiticus and production of aflatoxin by it at different incubation times. Mycoses. 2008;51:35–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elson L, Randu K, Feldmeier H, Fillinger U. Efficacy of a mixture of neem seed oil (Azadirachta indica) and coconut oil (Cocos nucifera) for topical treatment of tungiasis. A randomized controlled, proof-of-principle study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkar P, Acharyya S, Banerjee A, Patra A, Thankamani K, Koley H, et al. Intracellular, biofilm-inhibitory and membrane-damaging activities of nimbolide isolated from Azadirachta indica A. Juss (Meliaceae) against meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:1205–14. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harjai K, Bala A, Gupta RK, Sharma R. Leaf extract of Azadirachta indica (neem): A potential antibiofilm agent for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pathog Dis. 2013;69:62–5. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hussain F, Khurshid MF, Masood R, Ibrahim W. Developing antimicrobial calcium alginate fibres from neem and papaya leaves extract. J Wound Care. 2017;26:778–83. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.12.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Läuchli S, Vannotti S, Hafner J, Hunziker T, French L. A plant-derived wound therapeutic for cost-effective treatment of post-surgical scalp wounds with exposed bone. Forsch Komplementmed. 2014;21:88–93. doi: 10.1159/000360782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mainetti S, Carnevali F. An experience with paediatric burn wounds treated with a plant-derived wound therapeutic. J Wound Care. 2013;22:681–9. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.12.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franco P, Potenza I, Moretto F, Segantin M, Grosso M, Lombardo A, et al. Hypericum perforatum and neem oil for the management of acute skin toxicity in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiation or chemo-radiation: A single-arm prospective observational study. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:297. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yerbanga RS, Rayaisse JB, Vantaux A, Salou E, Mouline K, Hien F, et al. Neemazal ® as a possible alternative control tool for malaria and African trypanosomiasis? Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:263. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abiy E, Gebre-Michael T, Balkew M, Medhin G. Repellent efficacy of DEET, MyggA, neem (Azedirachta indica) oil and chinaberry (Melia azedarach) oil against Anopheles arabiensis, the principal malaria vector in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2015;14:187. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0705-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagini S. Neem limonoids as anticancer agents: Modulation of cancer hallmarks and oncogenic signaling. enzymes. 2014;36:131–47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802215-3.00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schumacher M, Cerella C, Reuter S, Dicato M, Diederich M. Anti-inflammatory, pro-apoptotic, and anti-proliferative effects of a methanolic neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf extract are mediated via modulation of the nuclear factor-κB pathway. Genes Nutr. 2011;6:149–60. doi: 10.1007/s12263-010-0194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ulbricht C, Chao W, Costa D, Rusie-Seamon E, Weissner W, Woods J. Clinical evidence of herb-drug interactions: A systematic review by the natural standard research collaboration. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:1063–120. doi: 10.2174/138920008786927785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suresha AR, Rajesh P, Anil Raj KS, Torgal R. A rare case of toxic optic neuropathy secondary to consumption of neem oil. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:337–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.121129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meeran M, Murali A, Balakrishnan R, Narasimhan D. “Herbal remedy is natural and safe”--truth or myth? J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:848–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Babu TA, Ananthakrishnan S. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension secondary to ingestion of Morinda coreia and Azadirachta indica leaves extract in infant. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013;4:298–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.119722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Page C, Hawes EM. Haemolytic anaemia after ingestion of Neem (Azadirachta indica) tea. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200890. bcr2013200890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernaola M, Valls A, de Frutos C, Garcia-Abujeta JL. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis to neem oil used in natural cosmetic. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82:389–90. doi: 10.1111/cod.13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sánchez-Gilo A, Nuño González A, Gutiérrez Pascual M, Vicente Martín FJ. Airborne allergic contact dermatitis caused by neem oil. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:449–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ambooken B, Abdulsalam S, Asokan N, Abraham A. Allergic contact stomatitis caused by neem leaves (Azadirachta indica) Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:376–8. doi: 10.1111/cod.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jadhav PB. Leucoderma on the lips induced by neem (Azadirachta indica): Case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:943–6. doi: 10.1111/ced.13635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karthikeyan K, Gopinath H, Kaleeswaran V, Vimal M. Leaves that leave their mark: A case series of pediatric Piper Betle-induced leukomelanosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:911–4. doi: 10.1111/pde.14272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suresh G, Gopalakrishnan G, Masilamani S. Neem for plant pathogenic fungal control: The outlook in the new millennium. In: Ind Koul O, Wahab S, editors. Neem: Today and in the New Millennium. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2004. pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehlhorn H, Al-Rasheid KA, Abdel-Ghaffar F. The Neem tree story: Extracts that really work. In: Melhorn H, editor. Nature Helps…. Parasitology research (Monographs 1) Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atanasov AG, Zotchev SB, Dirsch VM, Supuran CT. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:200–16. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.[Internet]. Fda.gov. 2021. [Last accessed on 2021 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/93113/download .

- 58.[Internet]. Cdsco.gov.in. 2021. [Last accessed on 2021 Jul 27]. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2018/UploadPublic_NoticesFiles/faqnd.pdf .