Abstract

Objectives:

Collision tumours are rare situations characterised by the coincidence of two different skin neoplasms in the same lesion.

Methods:

We have analyzed 41 collision skin tumours from one department in the clinical-dermoscopic-histopathologic correlations.

Results:

We present 41 collisions tumours. The mean age of our patients was 67.9 years, the mean diameter of the lesion was 11.6 mm. The most frequent locations were trunk (27 lesions) and head/neck (11 lesions). The collisions were classified as benign/benign (13 cases), benign/malignant (25 cases) and malignant/malignant (3 cases). The most frequent participants were seborrheic keratosis (24 cases), malignant melanoma (17 cases), melanocytic nevus (14 cases), basal cell carcinoma (12 cases) and heamangioma (10 cases). Thirty cases were of “dominant/minor” type and 11 cases of “half to half” type. Malignant tumours were a part of 28 collisions; these lesions were larger, patients were older and the malignant part was dominant in most cases. More than half of the collisions were unexpected by the initial clinical examination. Six collisions were missed by the initial histopathological examination.

Conclusions:

Collision tumours can be missed by clinical or even histopathological examination. Dermoscopy is very helpful in the recognizing of difficult cases and cooperating with the histopathologist.

KEY WORDS: Collision tumor, dermoscopy, histopathology, malignant melanoma

Introduction

Collision tumors are characterized by the coincidence of two or more different skin neoplasms in the same lesion. Many different skin tumors can be a part of a collision, including benign/benign, benign/malignant and also malignant/malignant associations. Some authors believe that the term compound tumor is more accurate to describe the possible relationship between both entities. Collision skin tumors are rare situations. From a clinical point of view, they are frequently very difficult to diagnose. Most of them are curiosities of little importance, they usually remain unnoticed or unrecognized. If a malignant tumor is involved in the collision, it is important to correctly identify the situation and surgically remove the tumor in an appropriate manner.

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive method that improves clinician's diagnostic accuracy of many pigmented and non-pigmented skin tumours.[1,2] It allows the identification of important structures and colors that may remain unnoticed during routine clinical examination by the naked eye. Dermoscopy can be crucial for the correct diagnosis even in clinically very difficult situations. That is why it can play an important role also in the diagnosis of collision situations.

Collision skin tumors are relatively rarely mentioned in the scientific literature. The vast majority of papers describe individual cases. To our knowledge, the only work introducing and analyzing a high number of collision situations in dermoscopic-histopathological correlation was a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopic Society. The authors collected 77 collision tumors from 21 pigmented lesion clinics in nine countries.[3] We present our group of 41 cases from a single department.

Materials and Methods

We have been systematically collecting collision tumors. All presented lesions were excised in our department between 2011 and 2019 and every collision situation was confirmed histopathologically. Only cases with required personal data were included. Digital dermoscopic images were taken before the excision in all cases (Microderm, Visiomed, Canfield Scientific) and they were available for further study. The clinical image of the excised lesion was available in 28 of 41 presented cases.

We were interested in the localization and size of all collision lesions, as well as the age and gender of all patients. We monitored the participation of individual diagnoses in collision situations based on histopathological examination. We divided the collisions into benign/benign, benign/malignant, and malignant/malignant types. We focused on collision tumors with a malignant component and analyzed them. We tried to find appropriate dermoscopic correlates for all histopathologically confirmed diagnoses in individual lesions. Based on dermoscopic images, we classified collision tumors as “dominant/minor lesions” with one predominant and the other repressed part of the collision or a “half to half lesions” with two almost equal parts of collision. We were also interested in whether some collision tumors remained unrecognized by clinical or histopathological examination.

Results

The presented group consists of 41 lesions from 41 patients (male 23, female 18). The mean age of our patients was 67.9 years (range from 38 to 89 years). Regarding the anatomic site; 27 lesions were located on the trunk (19 on the back), 11 lesions on the head and neck (8 on the face), 2 lesions on the upper extremities and 1 lesion on the lower extremities. The mean diameter of the lesion was 11.6 mm (range from 4 to 25 mm).

Based on the results of histopathological examination we found 40 collisions of two different tumors and 1 collision of three tumors [Figures 1–3]. Collision tumors were classified as benign/benign in 13 cases, benign/malignant in 25 cases and malignant/malignant in 3 cases. The most frequent participant of the collision was seborrheic keratosis in 24 cases, followed by malignant melanoma in 17 cases (melanoma in situ in 11 cases, invasive melanoma in 5 cases and melanoma metastasis in 1 case), melanocytic nevus in 14 cases (dermal nevus in 5 cases, atypical nevus in 5 cases, common junctional or compound nevus in 2 cases and blue nevus in 2 cases), basal cell carcinoma in 12 cases, hemangioma in 10 cases, carcinoma in situ in 2 cases, dermatofibroma in 1 case, sebaceous nevus in 1 case and viral wart in 1 case. All data are summarized in Table 1.

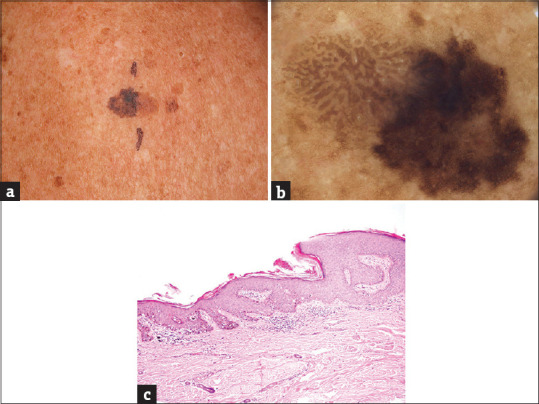

Figure 1.

(a) The collision of a seborrheic keratosis (left) and melanoma in situ (right) on the back of a 73-years old female patient, maximal diameter 18 mm. (b) The collision of a “half to half” type. Left (seborrheic keratosis): light brown parallel thick lines arranged in a cerebriform pattern. Right (melanoma in situ): dark brown reticular lines arranged in an irregular pigment network. (c) The part of acanthotic seborrheic keratosis on the left side; melanoma in situ on the right side (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

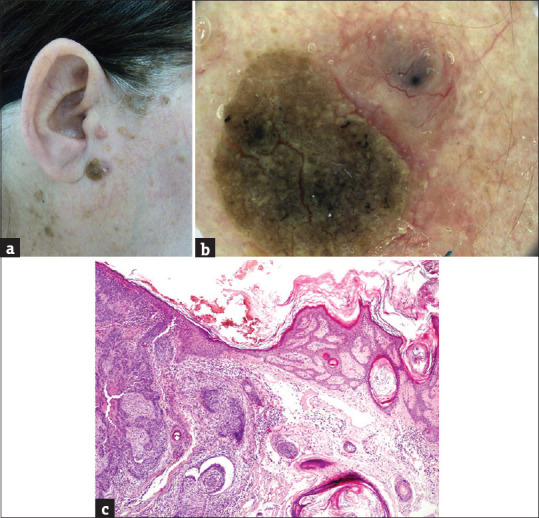

Figure 3.

(a) The collision of a seborrheic keratosis (left) and basal cell carcinoma (right) on the face of a 63-years old female patient, maximal diameter 11 mm. (b) The collision of a “half to half” type. Left (seborrheic keratosis): a verrucous mass of yellowish color. Right (basal cell carcinoma): pink nodule with many linear branching vessels and one large blue ovoid structure (blue clod). (c) Seborrheic keratosis on the left side; basal cell carcinoma on the right site (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

Table 1.

Collision skin tumours

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender (Male/Female) | Localization | Size (mm) | Diagnosis (Collision type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 DA | 57 | F | face | 12 | BCC/MN |

| 2 DB | 82 | F | trunk | 20 | SK/WART |

| 3 JB | 71 | F | face | 10 | BCC/MN |

| 4 AB | 76 | M | trunk | 10 | SK/MM |

| 5 MH | 69 | M | trunk | 9 | MN/SK |

| 6 LH | 76 | M | trunk | 25 | BCC/MM |

| 7 EH | 66 | F | trunk | 6 | MN/SK |

| 8 MCH | 60 | M | trunk | 10 | MN/SK |

| 9 VCH | 61 | M | trunk | 12 | MN/DF |

| 10 JK | 66 | M | arm | 6 | MM/HA |

| 11 MK | 63 | F | face | 11 | BCC/SK |

| 12 JK | 54 | M | trunk | 10 | MM/HA |

| 13 ZK | 87 | M | trunk | 25 | MM/SK |

| 14 JK | 38 | M | trunk | 20 | BCC/MN |

| 15 VL | 75 | M | trunk | 14 | MM/SK |

| 16 HL | 59 | F | scalp | 20 | SebN/BCC |

| 17 RM | 48 | M | trunk | 7 | HA/MN |

| 18 IM | 73 | F | trunk | 18 | MM/SK |

| 19 VM | 69 | F | face | 10 | BCC/MN |

| 20 FM | 81 | M | scalp | 15 | MM/CA is |

| 21 PN | 75 | M | trunk | 6 | BCC/SK |

| 22 VP | 56 | F | thigh | 10 | HA/MN |

| 23 JP | 76 | M | trunk | 7 | MN/SK |

| 24 AR | 74 | F | trunk | 20 | BCC/SK |

| 25 LR | 70 | F | face | 15 | MM/CA is |

| 26 JR | 80 | F | trunk | 10 | SK/HA |

| 27 FS | 74 | M | trunk | 11 | MM/SK |

| 28 IS | 42 | F | trunk | 4 | HA/SK |

| 29 FS | 70 | M | trunk | 15 | MM/SK |

| 30 ZS | 72 | M | trunk | 6 | SK/MM |

| 31 LT | 82 | F | neck | 8 | BCC/SK |

| 32 KT | 76 | M | trunk | 10 | MM/SK |

| 33 BT | 64 | F | face | 8 | HA/MN |

| 34 KU | 71 | M | trunk | 14 | MM/HA |

| 35 DV | 69 | F | face | 7 | MN/SK |

| 36 VV | 84 | M | trunk | 8 | MM/SK/HA |

| 37 JD | 40 | M | trunk | 8 | MN/SK |

| 38 JN | 79 | M | face | 8 | BCC/SK |

| 39 MK | 51 | M | arm | 6 | DF/BCC |

| 40 MH | 60 | F | trunk | 10 | MM/HA |

| 41 LD | 89 | F | trunk | 15 | MM/SK |

Column “Diagnosis (collision type)”: MM - all types of malignant melanoma, MN – all types of melanocytic nevi, SK – seborrheic keratosis, BCC – basal cell carcinoma, CA is – carcinoma in situ, HA – haemangioma, DF – dermatofibroma, WART – viral wart, SebN – sebaceous nevus. The boldface indicates the dominant diagnosis in collision tumour of “dominant/minor” type

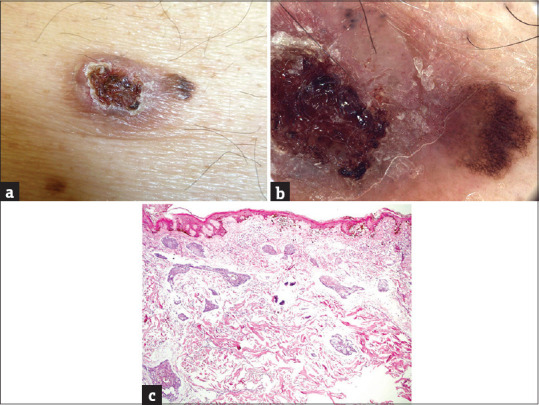

Figure 2.

(a) The collision of a basal cell carcinoma (left) and melanoma in situ (right) on the trunk of a 76-years old male patient, maximal diameter 25 mm. (b) The collision of a “dominant/minor” type. Left (basal cell carcinoma – dominant part): pink ulcerated nodule with large hemorrhage and keratin structures, few linear branching vessels and blue ovoid nests (blue clods) at the periphery. Right (melanoma in situ – minor part): dark brown reticular lines arranged in a largely regular pigment network, few grey-brown dots. (c) Melanoma in situ in the epidermis; basal cell carcinoma in the corium (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)

Malignant tumors were a part of collision in 28 cases. They collided most frequently with seborrheic keratosis (malignant melanoma/seborrheic keratosis in 11 cases and basal cell carcinoma/seborrheic keratosis in 5 cases). Patients with malignant tumors in collisions were older than the group average (mean age 70.4 years, range 38-89 years). Malignant lesions were also a bit larger (12.7 mm in diameter, range 6-25 mm). Collisions with malignant melanoma were typically located on the trunk (14 of 17 lesions) while those with basal cell carcinoma on the head and neck (7 of 12 lesions).

We found corresponding dermoscopic structures that correlate to histopathologically confirmed diagnoses in all studied cases and they are mentioned in Table 2. “Dominant/minor” tumors were identified in 30 cases while 11 lesions were of “half to half” type. If the lesion consisted of both benign and malignant tumors (25 benign/malignant cases) then the malignant part of the lesion was dominant in 15 cases, equal in 6 cases and minor in 4 cases.

Table 2.

Dermoscopic structures in colliding tumours

| Seborrheic keratosis (24 cases) | |

| milia-like/comedo-like structures | 13 cases |

| cerebriform pattern | 10 cases |

| fingerprint-like structures | 2 cases |

| hairpin vessels | 2 cases |

| network-like structures | 1 case |

| Malignant melanoma (17 cases): | |

| atypical pigment network | 15 cases |

| regression structures (blue/gray/white) | 10 cases |

| irregular pigmented globules/dots | 4 cases |

| negative network | 2 cases |

| asymmetric pigmentation around follicular openings | 1 case |

| Melanocytic nevi (14 cases): | |

| pigment network | 8 cases |

| comma-like vessels | 3 cases |

| homogenous blue pigmentation | 2 cases |

| pigmented globules | 1 case |

| Basal cell carcinoma (12 cases): | |

| arborizing vessels | 10 cases |

| pigmented structures (blue-gray ovoid nests/dots/globules, leaf-like) | 6 cases |

| ulceration | 5 cases |

| Haemangioma (10 cases): | |

| red lagoons with septae | 9 cases |

| blue-red structureless area, fibrosis, linear vessels | 1 case |

| Carcinoma in situ - actinic keratosis (2 cases): | |

| strawberry pattern, surface scaling | |

| Dermatofibroma (2 cases): | |

| central white patch with delicate network-like structures | |

| Viral wart (1 case): | |

| grouped papillae, looped vessels, haemorrhage. | |

| Sebaceous nevus (1 case) | |

| yellowish/brown aggregated globules |

The collision tumor was not reported by the initial histopathological examination in 6 cases. The second reading of histopathological samples was requested in these situations and it was guided by dermoscopic images. The benign minor part of the collision was originally missed in all these cases.

In the opposite situation, the collision tumor was not expected clinically in more than half of the presented cases (21 of 41 lesions). These data are based on medical documentation before the indication of excision. All patients were examined clinically by experienced dermatologists.

Discussion

Collision skin tumors are rare situations that represent a diagnostic challenge for dermatologists and also for histopathologists. They can be missed in daily routine, especially those of “dominant/minor” type where one of the tumors is masked by the second dominant part of the lesion. The experienced dermatologists did not clinically recognize a collision in more than half of our cases. The color of colliding lesions can play an important role in the clinical examination. If both parts of the collision are similarly colored, it is easier to overlook one of them (like basal cell carcinoma/dermal nevus or thin melanoma/flat seborrheic keratosis). In contrast, collisions of hemangioma with other pigmented tumors are easy to diagnose.[4] The collisions with malignant tumors are larger than benign/benign situations in our group. Moreover, the malignant tumor frequently represents a dominant part of the collision. Perhaps, this is only due to the fact that we are not able to recognize these collision situations earlier. Both malignant melanoma and basal cell carcinoma collided most frequently with seborrheic keratosis, probably because it is the most common skin tumor in old age. A collision of the seborrheic keratosis with melanoma can be easily overlooked in patients with multiple seborrheic keratoses.

Dermoscopy is a well-established diagnostic method that should be routinely used by the examination of skin tumors. It is crucial for the diagnosis of collision situations. Dermoscopy facilitates the identification of both tumors in the collision even in situations where one part of the lesion is overlooked by the clinical examination.[5,6] It also enables to choose the optimal treatment option. It is recommended to use dermoscopy for the examination of all atypical, asymmetric or multicolored skin tumors. It is important to examine all quadrants of the lesion by dermoscopy not to miss a possible “hidden” minor part of the collision.

Cooperation with a histopathologist is even more important than usual in the case of collision tumours.[7] The pathologist should receive enough information from the clinician about the examined lesion for ideal sectioning of the material. Histopathology can be guided by dermoscopic images. Transmission of either a dermoscopic image or a sketch of the collision would be most helpful especially in cases with a minor component of interest. Otherwise, many minor parts of the collision lesions may remain unrecognized even by histopathologists.

There have been only three large studies reported in the histopathologic literature on collision tumors. Boyd and Rapini reviewed 40 000 biopsies of skin lesions to find only 69 collision tumours.[8] The collision of basal cell carcinoma and melanocytic nevus was the most frequent one. Cascajo et al.[9] performed a retrospective analysis of 85 000 pathologic cases diagnosing 54 associations of seborrheic keratosis with malignant tumors of different type. Finally, Piérard and colleagues found 11 collisions of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma in a series of 78 000 primary cutaneous cancers.[10] The descriptions of individual cases have sporadically appeared in the literature for many years, an association of basal cell carcinoma with seborrheic keratosis was described by Sibley already in 1932.[11] Two different hypotheses explain the relationship between tumors in a collision.[12] First, a pathogenic relationship exists because two colliding tumors arise from similar cell origin. Second, the collision represents simply the coincidence of two different tumors in a similar location.

It is impossible to estimate the real incidence of collision skin tumors. The published papers either describe rare and interesting cases or analyses only excised and histopathologically confirmed tumours.[13,14,15,16] This is probably the reason for overreporting of the collisions with a malignant part, which is usually represented by basal cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma. On the contrary, the collisions of two benign lesions are probably the most common. These situations are frequently overlooked or if diagnosed properly, they are not biopsied and histopathologically confirmed. It seems to be clear that any combination of two different tumors (benign or malignant) in a collision is possible. As reported by Blum et al.,[3] many intrinsic and extrinsic factors can contribute to the likelihood of having two unrelated skin tumors occurring adjacent with each other. The frequency of individual tumors in collisions, their location and age distribution probably correspond to normal situations in the general population, which supports the theory of a simple coincidence of two tumors.

In agreement with the study of Blum et al.,[3] we can state that also in our group the most common participants in collision situations were melanocytic lesions, seborrheic keratoses and basal cell carcinomas. Melanocytic tumors and seborrheic keratoses were more frequent on the trunk while basal cell carcinomas on the head and neck. We found melanocytic nevi in younger patients than melanomas and epithelial tumors.

Conclusion

Collision skin tumors are rare situations. They can be simply missed by the clinical examination. Without the appropriate cooperation, they may remain unrecognized even by the histopathological examination. Dermoscopy is extremely helpful in the diagnosis of collision situations. It also offers important information for ideal sectioning and reading of histopathological samples. Last but not least, collision tumors offer valuable material for studying clinical-dermoscopical-histopathological correlations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:159–65. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, Menzies SW. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: A meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, Kreusch J, Cabo H, Campos-do-Carmo G, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS) Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51–62. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0704a12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tognetti L, Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Campoli M, Fimiani M, Rubegni P. Benign and malignant collision tumors of melanocytic skin lesions with hemangioma: Dermoscopic and reflectance confocal microscopy features. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24:313–7. doi: 10.1111/srt.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum A, Maltagliati-Holzner P, Deinlein T, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. Collision tumors in dermoscopy: A new challenge. Hautarzt. 2018;69:776–9. doi: 10.1007/s00105-018-4172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaballos P, Llambrich A, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy is useful for the recognition of benign-malignant compound tumours. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:653–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara G, Zalaudek I, Cabo H, Soyer HP, Argenziano G. Collision of basal cell carcinoma with seborrhoeic keratosis: A dermoscopic aid to histopathology? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:586–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd AS, Rapini RP. Cutaneous collision tumors. An analysis of 69 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cascajo CD, Reichel M, Sánchez JL. Malignant neoplasms associated with seborrheic keratoses. An analysis of 54 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:278–82. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piérard GE, Fazaa B, Henry F, Kamoun MR, Pierard-Franchimont C. Collision of primary malignant neoplasms on the skin: The connection between malignant melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. Dermatology. 1997;194:378–9. doi: 10.1159/000246154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibley K. Seborrhoeic verrucae and multiple basal-celled epitheliomata. Proc R Soc Med. 1932;25:926. doi: 10.1177/003591573202500667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornejo KM, Deng AC. Malignant melanoma within squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma: Is it a combined or collision tumor.--a case report and review of the literature? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:226–34. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182545e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jost M, Wehkamp U, Brasch J, Röcken C, Egberts F. Tumor on the flank. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:271–3. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medeiros PM, Alves NR, Silva CC, Faria PC, Barcaui CB, Piñeiro-Maceira J. Collision of malignant neoplasms of the skin: Basosquamous cell carcinoma associated with melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:39–42. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernardini MC, Moscarella E, Borsari S, Lallas A, Longo C, Piana S, et al. Collision tumors: A diagnostic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:e215–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salerni G, Lovatto L, Carrera C, Palou J, Alos J, Puig-Butille JA, et al. Correlation among dermoscopy, confocal reflectance microscopy, and histologic features of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma collision tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:275–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]