Abstract

Background:

Melatonin is a hormone that regulates the sleep–wake cycle and has immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory roles.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to assess melatonin levels and investigate the association with pruritus severity, sleep quality, and depressive symptoms in dermatoses with nocturnal pruritus.

Methods:

The study was a prospective study with 82 participants, including 41 patients and 41 healthy volunteers. The visual analog scale (VAS), Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were recorded for each patient. To assess the melatonin levels, urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin levels in the first urine in the morning were measured.

Results:

Melatonin concentrations were significantly lower (P = 0.007), while the BDI (P = 0.001) and PSQI (P = 0.001) scores were significantly higher in the patients with pruritus than in the healthy control subjects. There was an inverse correlation between melatonin levels and PSQI scores (r = −0.355, P = 0.023), and a positive correlation was detected between BDI scores and PSQI scores (r = 0.631, P = 0.001) in the pruritus group.

Conclusion:

Melatonin levels were found to decrease in relation to sleep quality in nocturnal pruritus patients. Low melatonin levels in these patients may be associated with sleep disorders and pruritus.

KEY WORDS: BDI, depression, melatonin, nocturnal pruritus, prurigo nodularis, PSQI, sleep quality

Introduction

Itching is a common discomforting symptom that significantly affects the quality of life. An increase in itching at night is a well-known characteristic of some skin diseases-such as prurigo nodularis (PN), lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), scabies, atopic dermatitis (AD), and some systemic diseases.[1] Therefore, the term nocturnal pruritus was put forward. Nocturnal pruritus is described as a discomforting condition that scratching during sleep temporarily relieves.[2] Although the pathophysiology is poorly understood, reasons such as skin barrier dysfunction and the associated increased transepidermal water loss (TEWL), cutaneous heat changes, and diurnal changes in the levels of the neuroendocrine hormones have been proposed.[1] One of the most important negative effects of nocturnal pruritus is the deterioration in the quality of sleep different components of sleep.[3] This association between itching and decreased quality of sleep was previously revealed with objective methods such as actigraphy and polysomnography in pediatric patients diagnosed with AD.[3,4,5]

Recently, studies focused on the relationship between skin disease and sleep have emerged.[6] The skin plays a role in normal sleep physiology by maintaining the core body temperature through thermoregulation. In addition, cutaneous symptoms such as pruritus and thermoregulation problems have negative effects on sleep quality.[6] On the contrary, the changes in serum melatonin and cortisol levels due to the circadian rhythm may trigger inflammatory skin disorders.[6]

Melatonin is a hormone that is produced in the pineal gland. Melatonin has a diurnal rhythm; its secretion increases at night and reaches peak levels between 02:00 a.m. and 04:00 a.m. The main function of melatonin is the regulation of the sleep–wake cycle.[7] In addition, its immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects have been demonstrated in recent years.[8] Melatonin shows its immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects by stimulating cytokine production in immunomodulatory cells.[9] It has been shown to provide the regression of the proinflammatory process by increasing C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.[10] Melanin also regulates skin barrier function and skin temperature. Deteriorations in melatonin levels have been detected in patients with AD and psoriasis, and the association with sleep disorders was revealed in patients with AD.[11,12] In addition, the use of melatonin has been demonstrated to improve AD symptoms and disease severity in patients with AD.[12,13,14]

Functional pruritus (FP) is a type of chronic pruritus in which psychological factors play a role in triggering, aggravation, or persistence of the disease. For FP diagnosis, the French Psychodermatology Group defined three compulsory/major criteria: localized or generalized pruritus sine materia, chronic pruritus (at least 6 weeks), and the lack of association with somatic cause.[15] Functional pruritus, PN, LSC, and neurotic excoriations (NE) are intense pruritic dermatoses associated with nocturnal pruritus. A common characteristic in the etiology of all the above disorders is the emotional-psychogenic triggers. There is a vicious itch–scratch cycle that is hard to break.

The study aims to investigate the complex association between melatonin mechanism pruritus severity, sleep quality, and depressive symptoms by investigating melatonin levels in patients with pruritus.

Methods

Participants and protocol

This case-control study was performed between December 2018 and March 2019. The study cohort consisted of patients aged between 18 and 65 years—41 with pruritus and 41 healthy control subjects suitable for testing for one melatonin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (performed on the same day) consisting of 82 plates. A power analysis was performed prior to study initiation to define the study population, and it revealed that at least 38 samples were needed for each group.

The pruritus group consisted of patients on admission recruited from the dermatology outpatient clinic, and the healthy control group consisted of our hospital staff volunteers. The patients with pruritus were subdivided into the following four categories: PN, NE, LSC, and FP. The diagnosis was put with clinical and histopathological findings. AD was excluded in all patients by using the Hanifin and Rajka diagnosis criteria. Scabies and other skin diseases that may cause itching were excluded by clinical and histopathological findings. FP was diagnosed according to the diagnosis criteria of the French Psychodermatology Group.[15] Patients with a history of any topical or systemic pruritus therapy such as topical-systemic corticosteroid, systemic antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotic drugs, and use of medication for insomnia were excluded from the study. Systemic illnesses, including acute or chronic infection, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid disorders, chronic renal or liver disease, inflammatory disease, and neurologic or psychiatric disease, were also excluded by patient history and basic laboratory investigations. Accordingly, blood samples were collected from each patient to measure serum glucose, renal-hepatic function tests, total blood count, and total IgE levels; in addition, urine analysis was performed to detect urinary infection, proteinuria, and glucosuria.

At the initial visit, each patient's age, sex, visual analog scale (VAS), and the scores of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were recorded. All the participants signed a written informed consent form after being provided with a full explanation of the purpose and nature of the study and the related procedures. The study was approved by the Şişli Hamidiye Etfal Training and Research Hospital's ethics committee.

Data collection tools

Visual analog scale: The VAS was used in the evaluation of the severity of itching in patients. This scale ranged from 0 (no itching) to 10 (severe itching).

Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index: The PSQI questionnaire was developed by Buysse et al., and the validation was performed by Agargün et al.[16] The questionnaire allows a subjective assessment of sleep quality in the previous month. The PSQI is a self-rating test consisting of 19 questions. The questionnaire has seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component of the PSQI was scored on a scale of 0–3, and the global score was calculated between 0 and 21. High scores obtained from the questionnaire are signs of deterioration in the quality of sleep. A PSQI score higher than 5 is considered a deterioration in the quality of sleep.

Beck Depression Inventory: This self-reporting questionnaire was developed by Beck et al., and the Turkish validation was performed by Hisli et al.[17] The test consists of 21 questions aimed at assessing the degree of depression. The questions are scored between 0 (symptom absent) and 3 (severe symptoms), and the highest score is calculated as 63. The higher scores represent signs of increased depressive levels.

Evaluation of melatonin

The 6-sulphatoxymelatonin (aMT6s) levels in urine samples were measured to evaluate the melatonin levels of all the participants. aMT6s is a melatonin metabolite found in urine. The aMT6s level measured from the first urine in the morning reflects the amount of melatonin secreted all through the night. The first urine samples were taken from patients in the morning (08:00 a.m. –09:00 a.m.). The samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was taken for biochemical analysis. The samples were stored at −80°C. The aMT6s levels in the urine samples were evaluated using the ELISA method (Elab science, E-EL-H1726, USA).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of the evaluation results were given as the mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum scores for the numerical variables and as numbers and percentages for the categorical variables. The comparison of the independent variables in both groups was performed using the Student's t test when there was a normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U test when there was no normal distribution. The comparison was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test when there were more than two groups. The subgroup analyses were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and interpreted using the Bonferroni correction. The associations between the numerical variables were investigated using Spearman's correlation analysis because the parametric test condition could not be provided. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) test was used to find the association of variables on melatonin levels. The statistical alpha significance level was accepted as P < 0.05.

Results

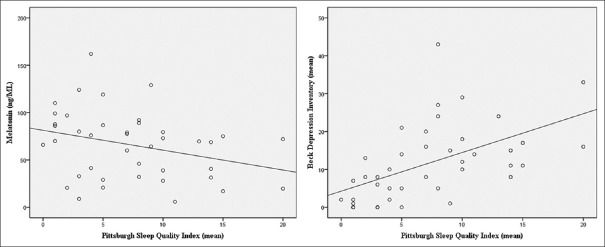

The study group consisted of 82 individuals: 41 patients and 41 healthy volunteers. There was no difference regarding gender ratio and age between the groups. There were 23 patients (56.1%) with FP, eight patients (19.5%) with PN, seven patients (17.1%) with LSC, and three patients (7.3%) with NE [Table 1]. The melatonin concentrations, VAS, BDI, and PSQI values of the patients with pruritus and the control subjects are summarized in Table 2. Although mean ± SD melatonin concentration was significantly lower in patients with pruritus than in the healthy control subjects (65.97 vs. 104.02 ng/mL, P = 0.007), BDI and PSQI values were significantly higher in the pruritus group than in the healthy control subjects (11.73 vs. 1.12, P = 0.001 and 7.32 vs. 0.73, P = 0.001, respectively) [Table 2]. The PSQI values were found to be higher than 5 in 63.4% of the pruritus groups and 0% of the healthy controls. No statistically significant association was detected between the VAS scores and melatonin, BDI, and PSQI levels in the patient group (P = 0.631, P = 0.524, and P = 0.364, respectively). There was an inverse correlation between melatonin levels and PSQI scores (r = −0.355, P = 0.023), and a positive correlation was detected between BDI scores and PSQI scores (r = 0.631, P = 0.001) in the pruritus group [Table 3 and Figure 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of pruritus and healthy control groups

| Pruritus (n=41) | Healthy controls (n=41) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 41.76±14.7 | 38.51±11.7 | a0.284 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 9 (22) | 15 (36.6) | b0.14 |

| Female | 32 (78) | 26 (63.4) | |

| Pruritus classification, n (%) | |||

| Functional pruritus | 23 (56.1) | ||

| Prurigo nodularis | 8 (19.5) | ||

| Lichen simplex chronicus | 7 (17.1) | ||

| Neurotic excoriation | 3 (7.3) |

aP for Student’s t-test comparing age among patients with pruritus and healthy controls. bP for the Yates continuity correction test comparing gender ratio among patients with pruritus and healthy controls

Table 2.

Comparison of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), visual analog scale (VAS), and melatonin levels between pruritus and healthy controls. Statistically significant P values are highlighted in bold

| Pruritus (n=41) mean±SD | Healthy controls (n=41) mean±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 11.73±10.01 | 1.12±2.77 | a0.001** |

| PSQI | 7.32±5.23 | 0.73±0.98 | a0.001** |

| Melatonin, ng/mL | 65.97±35.72 | 104.02±65.39 | a0.007* |

| VAS | 7.83±1.63 |

aMann-Whitney U Test *P<0.05, **P<0.001

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between scores of BDI, PSQI, VAS, and melatonin levels. Statistically significant P values are highlighted in bold

| VAS | Melatonin | BDI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| rho | P | rho | P | rho | P | |

| Patient group | ||||||

| Melatonin | −0.077 | 0.631 | ||||

| BDI | 0.102 | 0.524 | −0.095 | 0.556 | ||

| PSQI | 0.146 | 0.364 | −0.355 | a0.023* | 0.631 | a0.001** |

aSpearman’s correlation analysis *P<0.05, **P<0.001

Figure 1.

The correlations of PSQI scores between melatonin level and BDI scores in the pruritus group

When the patients with pruritus were evaluated according to the disease subgroups, there was a statistically significant difference in the means of BDI and PSQI values (P = 0.007 and P = 0.007, respectively). BDI scores were significantly lower in the LSC subgroup compared to the FP and PN subgroups (P = 0.003 and P = 0.009, respectively). In addition, PSQI scores were significantly lower in the LSC subgroup compared to the FP and NE subgroups (P = 0.006 and P = 0.009, respectively) [Table 4].

Table 4.

BDI, PSQI, VAS, and melatonin levels according to pruritus classification

| Pruritus classification mean±SD (med) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| FP (n=23) | PN (n=8) | LSC (n=7) | NE (n=3) | ||

| BDI | 14.17±10.28 (13) | 15±9.5 (15.5) | 3±4.32 (1) | 4.67±4.16 (6) | d0.007* |

| PSQI | 8.7±4.43 (8) | 8.63±6.14 (7.5) | 3.57±5.13 (1) | 2±1 (2) | d0.007* |

| VAS | 7.91±1.81 (8) | 7.88±1.64 (7.5) | 7.71±1.25 (8) | 7.33±1.53 (7) | d0.881 |

| Melatonin | 68.03±37.21 (72) | 56.51±33.67 (50.3) | 67.26±39.36 (80) | 72.43±34.64 (87.6) | d0.685 |

dKruskal-Wallis Test. *P<0.05. FP, functional pruritus; PN, prurigo nodularis; LSC, lichen simplex chronicus; NE, neurotic excoriation

Age- and BDI-adjusted ANCOVA revealed significantly different associations between patients and healthy control groups on melatonin level (P = 0.01).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare melatonin levels and the association with BDI and PSQI scores in patients with nocturnal pruritus and healthy control subjects. We found that melatonin levels were significantly lower in patients with nocturnal pruritus accompanied by PN, LSC, NE, and FP than in healthy control subjects. Lower melatonin levels were associated with deterioration in the quality of sleep. There is a significant association between an increase in melatonin levels and getting to sleep.[18,19] The mechanism by which melatonin induces sleep transition is unclear; however, it has been reported that sleep transition can provide a sedative effect and decrease the body temperature.[19] The lower melatonin level in our study might be the cause of sleep disorders in the patients. Many studies have demonstrated the association of lower melatonin levels with sleep disorders. Melatonin levels have been found to be lower in insomnia patients when compared with melatonin levels in patients of the same age group patients who had healthy sleeping behaviors.[20] In addition, the correlation between nocturnal melatonin levels and sleep disorders in various systemic diseases and in children with AD has been demonstrated.[3,21] Another cause of sleep disorders might be pruritus and the feeling of discomfort associated with pruritus. Various studies in the literature have demonstrated that pruritus causes deterioration in the quality of sleep in systemic and skin diseases.[3,22] Sleep disturbance was reported in 33%–87.1% in adults with AD, and deterioration in the quality of sleep was reported as 61% in patients with chronic kidney disease associated with pruritus.[22,23] In this study, deterioration in the quality of sleep of the patients was found to be 63.4%. Bender et al. demonstrated that there is a correlation between disease severity and deterioration in the quality of sleep in patients with AD.[5]

The pathogenesis of nocturnal pruritus has not been clarified yet; however, different mechanisms have been suggested for the cause of nocturnal pruritus.[1,2] One of the possible mechanisms is the circadian rhythm changes in skin temperature and TEWL. Skin temperature is known to increase at night.[24] Researchers have suggested that pruritus feeling increases with the stimulation of nerve endings, which increases with temperature. TEWL significantly increases at night and decreases in the morning. The entrance of agents, which cause skin irritation and itching, is facilitated by an increase in the TEWL.[24] In addition, impairment of skin barrier function at night, leading to greater TEWL, is believed to increase pruritus.[25] Another mechanism is associated with corticosteroid levels. Corticosteroid levels decrease at night in the hypothalamus–pituitary axis. Therefore, the inflammatory effect of corticosteroids decreases during this period, and exacerbation may be detected in inflammatory skin diseases.[1] The increase of the proinflammatory cytokines at night and exacerbation of pruritus due to the circadian patterns of cytokines and prostaglandins appears to be another possible cause.[1]

In recent years, various studies have been conducted with different disease groups demonstrating the anti-inflammatory effect of melatonin. Melatonin has been shown to suppress inflammation by decreasing the production of various proinflammatory cytokines—mainly, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α—with the regulation of cytokine production in immunocompetent cells.[9] In addition, melatonin contributes to the suppression of the inflammatory process by decreasing CRP levels.[10] In light of these data, its anti-inflammatory effect has been found to be useful in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and ulcerative colitis.[26,27] Similarly, in dermatology, disturbances in melatonin levels have been observed in inflammatory skin diseases such as AD and psoriasis and have been found to correlate with disease severity in both diseases. Skin inflammation has a significant role in the etiology of nocturnal pruritus. Thus, a decrease in melatonin levels might cause an increase in skin inflammation due to the inflammatory functions of melatonin, which might cause an increase in pruritus. This is a cycle with elements that positively affect each other: a decrease in melatonin levels causes pruritus sleep disorder. In addition, Cikler et al.[28] showed that melatonin treatment reduced mast cell infiltration at the dermis in stress-induced skin diseases in rat models. These findings suggest that melatonin is a molecule that can play a role in the pathogenesis of pruritus.

The depressive symptoms were evaluated with BDI in this study and were found to be higher in patients with nocturnal pruritus than in the control group. The analysis revealed a positive correlation between depressive symptoms and quality of sleep. An inverse correlation between melatonin levels and PSQI scores and a positive correlation between BDI and PSQI scores were detected in the pruritus groups. However, no association was detected between the depressive symptoms and the melatonin levels in the pruritus group. In a previous study involving psoriasis patients, melatonin level was not found to be associated with depressive symptoms.[11] The association between melatonin and depression is controversial: lower melatonin levels have been demonstrated in depression; however, some studies have reported the contrary.[29,30] Caumo et al.[30] reported that the levels of melatonin during daytime hours were higher in patients with a major depressive disorder than in the control group. Moreover, a correlation between melatonin levels and the severity of depressive symptoms was found among these patients.[30]

Many recent studies on the use of melatonin and melatonin receptor analogs in treatment have been carried out. Some evidence support the use of melatonin in the treatment of various systemic diseases, including cancer, skin diseases, and sleep disorders.[29,30,31,32] Melatonin has been used to treat sleep disorders such as insomnia and jet lag (to repair sleep onset latency, duration, and quality) and was reported to be effective and safe.[33,34] Melatonin has also been found to be effective in the treatment of psychiatric diseases, such as depression, and systemic diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and inflammatory bowel disease.[26,27,32] Some studies have been conducted to demonstrate the usefulness of melatonin in dermatological treatment in children.[12,13] Chang et al. [23] showed that melatonin treatment- ameliorates the sleep onset latency and reduces disease severity in patients with AD. Ardakani et al.[12] showed that melatonin improves disease severity, sleep quality, and total IgE levels in patients with AD. It is recommended for the management of sleep disorders in patients with AD.[35] Interestingly, amelioration was detected in disease severity with the amelioration in sleep disorders in these patients, which reminds the anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin. Its use in inflammatory skin disease may be suggested in the future. It may also be helpful in correcting these symptoms in patients with depressive symptoms, as in the patient group of this study.

This study has some limitations. First, the sample size of the study was small. Second, the study used only questionnaires to assess sleep quality and disease severity. Collecting one urine sample to measure melatonin level may be accepted as a limitation because collecting two or more urine samples on different days is more appropriate to achieve optimal values. However, the first study with this patient group on this subject represents the strength of the study. In addition, this study is unique in that it focused on the direct correlation between melatonin levels and PSQI and BDI values. Further studies are required to investigate the role of melatonin in the pathogenesis of pruritus and nocturnal pruritus, and its association with depressive disorders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found decreased melatonin levels in patients with nocturnal pruritus. These levels had an inverse correlation with PSQI scores, which may indicate a pathogenetic cofactor contributing to the development of the disease and deterioration in the quality of sleep. The administration of melatonin to patients with nocturnal pruritus may be useful in improving the quality of sleep and decreasing disease severity. Therefore, melatonin may be considered an alternative in the treatment of nocturnal pruritus, a complicated disease that is difficult to treat and manage.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Patel T, Ishiuji Y, Yosipovitch G. Nocturnal itch: Why do we itch at night? Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:295–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boozalis E, Grossberg AL, Püttgen KB, Cohen BA, Kwatra SG. Itching at night: A review on reducing nocturnal pruritus in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:560–5. doi: 10.1111/pde.13562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang YS, Chou YT, Lee JH, Lee PL, Dai YS, Sun C, et al. Atopic dermatitis, melatonin, andsleep disturbance. Pediatrics. 2014;134:397–405. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camfferman D, Kennedy JD, Gold M, Martin AJ, Lushington K. Eczema and sleep and its relationship to daytime functioning in children. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender BG, Ballard R, Canono B, Murphy JR, Leung DY. Disease severity, scratching, and sleep quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:415–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Sleep-wake disorders and dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brzezinski A. Melatonin in humans. N Eng J Med. 1997;336:186–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrero JM, Reiter RJ. Melatonin-immune system relationships. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:167–79. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrillo-Vico A, Lardone PJ, Alvarez-Sánchez N, Rodríguez-Rodríguez A, Guerrero JM. Melatonin: Buffering the immune system. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:8638–83. doi: 10.3390/ijms14048638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agil A, Reiter RJ, Jimenez-Aranda A, Iban-Arias R, Navarro-Alarcon M, Marchal JA, et al. Melatonin ameliorates low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress in young Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Pineal Res. 2013;54:381–8. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kartha LB, Chandrashekar L, Rajappa M, Menon V, Thappa DM, Ananthanarayanan PH. Serum melatonin levels in psoriasis and associated depressive symptoms. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:123–5. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taghavi Ardakani A, Farrehi M, Sharif MR, Ostadmohammadi V, Mirhosseini N, Kheirkhah D, et al. The effects of melatonin administration on disease severity and sleep quality in children with atopicdermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29:834–40. doi: 10.1111/pai.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang YS, Lin MH, Lee JH, Lee PL, Dai YS, Chu KH, et al. Melatonin supplementation for children with atopic dermatitis and sleep disturbance: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:35–42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TH, Jung JA, Kim GD, Jang AH, Ahn HJ, Park YS, et al. Melatonin inhibits the development of 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesionsin NC/Nga mice. J Pineal Res. 2009;47:324–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misery L, Alexandre S, Dutray S, Chastaing M, Consoli SG, Audra H, et al. Functional itch disorder or psychogenic pruritus: Suggested diagnosis criteria from the French psychodermatology group. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:341–4. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. Beck depression inventory (BDI) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brzezinski A, Vangel MG, Wurtman RJ, Norrie G, Zhdanova I, Ben-Shushan A, et al. Effectsof exogenous melatonin on sleep: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sack RL, Hughes RJ, Edgar DM, Lewy AJ. Sleep-promoting effects of melatonin: At what dose, in whom, under what conditions, and by what mechanisms? Sleep. 1997;20:908–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.10.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajak G, Rodenbeck A, Staedt J, Bandelow B, Huether G, Rüther E. Nocturnal plasma melatonin levels in patients suffering from chronic primary insomnia. J Pineal Res. 1995;19:116–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1995.tb00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto AR, da Silva NC, Pinato L. Analyses of melatonin, cytokines, and sleep in chronic renal failure. Sleep Breath. 2016;20:339–44. doi: 10.1007/s11325-015-1240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rehman IU, Lai PS, Lim SK, Lee LH, Khan TM. Sleep disturbance among Malaysian patients with end-stage renal disease with pruritus. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:102. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis:A 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yosipovitch G, Xiong GL, Haus E, Sackett-Lundeen L, Ashkenazi I, Maibach HI. Time-dependent variations of the skin barrier function in humans: Transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin surface pH, and skin temperature. J Jnvest Dermatol. 1998;110:20–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee CH, Chuang HY, Shih CC, Jong SB, Chang CH, Yu HS. Transepidermal water loss, serum IgE and beta-endorphin as important and independent biological markers for development of itch intensity in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1100–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chojnacki C, Wisniewska-Jarosinska M, Walecka-Kapica E, Klupinska G, Jaworek J, Chojnacki J. Evaluation of melatonin effectiveness in the adjuvant treatment of ulcerative colitis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:327–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farez MF, Calandri IL, Correale J, Quintana FC. Antiinflammatory effects of melatonin in Multiple sclerosis. Bioessays. 2016;38:1016–26. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cikler E, Ercan F, Cetinel S, Contuk G, Sener G. The protective effects of melatonin against water avoidance stress-induced mast cell degranulation in dermis. Acta Histochem. 2005;106:467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dmitrzak-Weglarz M, Reszka E. Pathophysiology of depression: Molecular regulation ofmelatonin homeostasis-current status. Neuropsychobiology. 2017;76:117–29. doi: 10.1159/000489470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caumo W, Hidalgo MP, Souza A, Torres IL, Antunes LC. Melatonin is a biomarker of circadian dysregulation and is correlated with major depression and fibromyalgia symptom severity. J Pain Res. 2019;12:545–56. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S176857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Li S, Zhou Y, Meng X, Zhang JJ, Xu DP, et al. Melatonin for the prevention and treatmentofcancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39896–921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin GJ, Huang SH, Chen SJ, Wang CH, Chang DM, Sytwu HK. Modulation by melatonin of the pathogenesis of inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:11742–66. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahteenmaki R, Puustinen J, Vahlberg T, Lyles A, Neuvonen PJ, Partinen M. Melatonin forsedative withdrawal in older patients with primary insomnia: A randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:975–85. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Z, Chen F, Li WA, Geng X, Li C, Meng X, et al. A review of sleep disorders andmelatonin. Neurol Res. 2017;39:559–65. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2017.1315864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel D, Levoska M, Shwayder T. Managing sleep disturbances in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:428–33. doi: 10.1111/pde.13444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]