Abstract

Protein glycosylation is a common and highly heterogeneous post-translational modification that challenges biophysical characterization technologies. The heterogeneity of glycoproteins makes their structural analysis difficult; in particular, hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) often suffers from poor sequence coverage near the glycosylation site. A pertinent example is the Fc gamma receptor RIIIa (FcγRIIIa, CD16a), a glycoprotein expressed on the surface of natural killer cells (NK) that binds the Fc domain of IgG antibodies as a trigger for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). Here we describe an adaptation of a previously reported method using PNGase A for post-HDX deglycosylation to characterize the binding between the highly glycosylated CD16a and IgG1. Upon optimization of the method to improve sequence coverage while minimizing back-exchange, we achieved coverage of four of the five glycosylation sites of CD16a. Despite some back-exchange, trends in HDX are consistent with previously reported CD16a/IgG-Fc complex structures; furthermore, binding of peptides covering the glycosylated asparagine-164 can be interrogated when using this protocol, previously not seen using standard HDX-MS.

Graphical Abstract

Glycosylation is a highly abundant and heterogeneous post-translational modification fundamental to a variety of physiological processes. Most extracellular protein domains are glycosylated, and their diverse glycoforms influence cellular communication, recognition, and protein conformational stability.1–3 More specifically, cells of the innate and adaptive immune system use extracellular glycosylation for a variety of purposes including pathogen-associated glycosylation pattern recognition, endocytosis regulation, and immunoglobulin effector function.3 Because glycosylation is prolific and critical, changes in the composition of the glycome can have widespread detrimental effects that cause congenital disorders, viral immune escape and cancer cell metastasis;2–5 their impact and the extracellular nature of many glycoproteins make them apt drug targets.

The innate and adaptive immune responses have been increasingly exploited to produce a variety of treatments and to probe populations of specific immune cells. Both applications rely on antibody/target-cell high affinity binding, which is largely dependent on the glycosylation state of the antibody2, 6 and the receptor.7–9

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) is an immune response mechanism that can recognize and kill cells expressing tumor- or pathogen-derived antigens. For example, trastuzumab10 and rituximab11 are engineered mAbs that target specific cell-surface receptors associated with breast cancer cells (HER2) and B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (CD20), respectively; both molecules consist of uniquely engineered antigen binding fragments (Fab) and a human IgG1 constant Fc domain that can bind Fc receptor-bearing effector cells to precipitate ADCC. Fc gamma receptor III (FcγRIII or CD16) is the most common Fc receptor on the surface of natural killer (NK) cells, a type of cytotoxic lymphocyte utilized by ADCC to kill tumor and non-self cells.

CD16a consists of a transmembrane domain and a highly glycosylated extracellular domain responsible for binding with IgG Fc domains. CD16a has five potential asparagine-linked (N-linked) glycosylation sites (N38, N45, N74, N162, and N169). Consequently, at least 30 unique glycoforms of CD16a have been identified;8 the molecular weight distribution of CD16a is notoriously broad and tens of kDa larger than the predicted molecular weight of the nonglycosylated protein. Notably, N45 and N162 glycosylation were previously reported to participate in or influence Fc binding.12–13

Glycan heterogeneity, flexibility, and relatively large size present an inherent challenge to structural characterization techniques. Without pre-analysis deglycosylation, mass spectrometry-based proteomics analyses can suffer from poor coverage, especially via heterogeneity-induced signal attenuation, often resulting in an absence of information for whole regions surrounding the glycan. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), a chemical footprinting technique sensitive to changes in backbone amide hydrogen bonding and solvent accessibility, is attractive for probing conformational changes and binding sites.14–15 The extent of deuterium incorporation from exchange with the solvent is directly monitored via MS either on a global-level or using bottom-up analyses to isolate peptide-level sometimes approaching residue-level information. The largest issues for bottom-up HDX-MS analyses are the reversibility of the exchange and the peptide coverage (i.e., the extent of proteolytic digestion and the MS/MS-based identification of peptide fragments). Owing to HDX reversibility, careful attention must be paid to post-exchange sample manipulation including its temperature, time, and pH,16–17 and the approaches to circumvent this issue are limited. Ideally, the low pH (~2.5) quenched HDX sample should be promptly frozen or injected onto a cold LC system with online pepsin digestion to minimize back exchange of deuterated backbone amides, but compromises are often necessary to acquire coverage of relevant regions of difficult proteins.

HDX-MS analysis of glycosylated peptides is further complicated by glycan acetamido groups and linking asparagine side chains retaining deuterium; HDX-MS of a glycopeptide does not report solely on the backbone amides.18 One approach to HDX-MS analysis of the effect of glycosylation on structure and binding can be to focus on sites remote to glycosylation provided these are regions of interest. Houde et al.6, 19 showed glycosite-remote conformational changes and binding sites with respect to various N297-IgG glycoforms. We previously reported the HDX-MS resolved binding site of CD16a with IgG without using any deglycosylation and could not find the protein-protein contacts around N162 that were reported by X-ray crystallography.20–21, 22 Another common technique for glycoprotein analyses is to deglycosylate the protein prior to analysis, thereby decreasing the issue of heterogeneity. For example, N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) is the most used glycosidase for N-glycan removal, but it is inactive under acidic conditions and, thus, incompatible with post-HDX deglycosylation. Deglycosylation prior to HDX labelling has the potential to affect both the native fold of the protein and the binding affinity of a protein complex. With respect to CD16a, de-glycosylation is known to affect its binding affinity for IgG1, and, thus, de-glycosylation prior to HDX is not appealing.7–9

Alternatively, Jensen et al. 23 demonstrated a protocol for the deglycosylation of HDX-labelled trastuzumab by using a glycosidase active under acidic conditions, N-glycosidase A (PNGase A). Denaturation and especially disulfide reduction is critical for bottom-up HDX analysis of antibodies and CD16a; without disulfide reduction with reducing agents such as tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), bottom-up analyses can suffer from poor sequence coverage of cysteine-containing regions. Jensen et al.23 showed that PNGase A suffers significant loss in activity with denaturants and TCEP incubation, but some tolerance to just TCEP. That laboratory24 recently expanded the protocol using an alternative acidic glycosidase, PNGase H+, that exhibits broader glycan specificity and more tolerance to TCEP. Using PNGase H+, the authors acquired near complete coverage of the α1-antichymotrypsin that was glycosylated 5 times.

Here we present an extension of the protocol using PNGase A for the HDX-MS analysis of the CD16a binding site with rituximab to extract more binding information on the region of N162 and on the effect of N162 glycosylation on binding. The protocol should be effective for other glycosylated proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL

Post-HDX deglycosylation optimization, sample preparation, and analysis was carried out similarly to that reported by the Rand group.23–24 Briefly, after incubation with 90% v/v D2O/H2O (pD 7.4), CD16a was quenched with a pepsin-coupled beads slurry in a citric acid buffer, with 0.2 M TCEP (final pH 2.5), and incubated for 10-min. at 11 °C for optimized digestion. The beads were removed by centrifugal filtration, and the resulting peptides deglycosylated with PNGase A for 4 min. at 11 °C. The samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for later LC-MS analysis (details in SI). All HDX samples were analyzed in duplicate.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

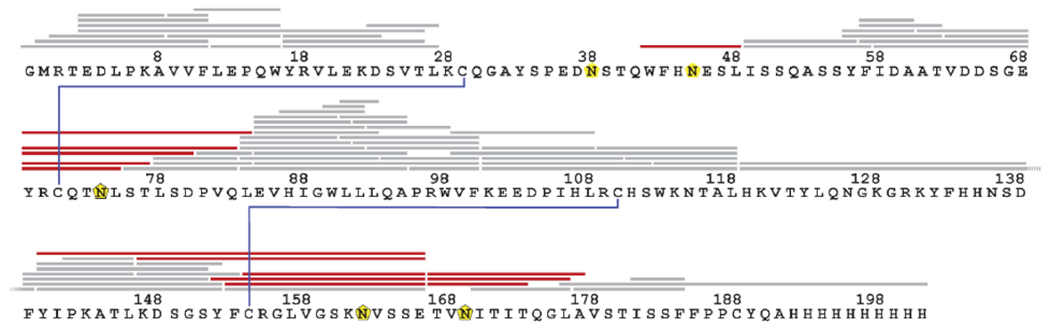

Using only pepsin digestion and disulfide reduction, we found peptides covering 78% of CD16a (Figure 1 (gray)). Notably, those regions not observed contain four of the five glycosylation sites (i.e., N38, N45, N74, and N169). Despite manual searching of the MS data, no glycopeptides could be found, likely owing to heterogeneity-induced signal attenuation and/or poor fragmentation. Jensen et al.23 previously reported the use of PNGase A for post-HDX de-glycosylation of trastuzumab under acidic conditions. Briefly, the HDX of trastuzumab was quenched using a suspension of pepsin beads in citric acid/TCEP solution (pH 2.5) and incubated for 4 min on ice. The pepsin beads were then removed using centrifugal filtration, and the peptide mixture deglycosylated for 2 min on ice. Direct implementation of this method for CD16a was unsuccessful in producing deglycosylated peptides, likely because the digestion was inefficient and the number of potential glycosites for CD16a is 5 times greater than for trastuzumab.

Figure 1.

Post-HDX deglycosylation of CD16a improves coverage of glycol-sites. LC-MS/MS identified peptides of CD16a after 10-min incubation with pepsin beads at 11 °C (grey), yielding added unique deglycosylated peptides after post-pepsin 4-min deglycosylation with PNGase A at 11 °C (red). Glycosylation sites are indicated with yellow pentagons, disulfide bonds are in blue.

As reported by Jensen et al.,23 the selection of an alternative quench/denaturant would attenuate PNGase A activity; therefore, to increase the coverage of CD16a, we evaluated the production of CD16a peptides as a function of the pepsin-bead incubation temperature and time, the extent of back-exchange under these conditions, and the time for the PNGase A incubation. Optimization found that a 10-min incubation with pepsin beads at 11 °C followed by a 4-min incubation with PNGase A at 11 °C resulted in the best coverage of CD16a with minimal back-exchange (Figures S1–S6). The optimized post-HDX deglycosylation protocol produced an average of 54% back-exchange (median 53%, range 39-80%); Jensen et al.23 reported an average H/D back-exchange extent of 43% for their optimized post-HDX deglycosylation conditions.

Using the optimized conditions, we observed 12 unique deglycosylated peptides covering four of the five glycosylation sites (N45, N74, N162, and N169), increasing the coverage to 93% (Figure 1 (red)). There was no coverage of N38, even under the harshest conditions. Zeck et al.25 reported no peptides or glycopeptides covering N38 when performing bottom-up characterization of CD16a from CHO and HEK293 cells, despite more rigorous digestion than allowable for HDX. Further optimization might improve this region’s coverage; however, any further sample manipulations would increase back-exchange.

Jensen et al.23 suggested that de-glycosylation efficiency may be affected by peptide length. We found, however, no correlation (Figure S7) but instead a dependence on glycosylation site. The identity of the glycan at each of the sites is reportedly variable,.25 which may be responsible for inefficient deglycosylation at the different sites.

Of the five glycosylation sites, those with have the largest influence on IgG1 binding are N45 and N162. N45 glycosylation has an inhibitory effect on IgG1-Fc binding owing to steric hinderance,13, 26 and N162 glycosylation can induce higher or lower binding affinity with the IgG1-Fc domain depending on the glycan’s identity.13, 27 CD16a binding the IgG Fc domain is typified by N162 glycan insertion into the IgG Fc domain, enabling protein-protein, CD16a-N162 glycan-Fc protein, and CD16a-N162 glycan-Fc glycan interactions.26, 28 Both glycosites are covered when using post-HDX de-glycosylation methods.

We observed multiple peptides covering N162 by using the optimized post-HDX de-glycosylation method. Interestingly, a peptide (153-166) covering the N162 glycosylation site is found with and without deglycosylation (i.e., nonglycosylated, or some population of CD16a is not glycosylated at N162 in the original sample (Figure 2)). PNGase A deglycosylation of an N-linked glycopeptide manifests as deamidation of the asparagine; thus the deglycosylated and non-glycosylated states of the peptide are differentiable by using both LC separation and MS (Figure 2A). The apparent asparagine deamidation results in a mass shift of +0.98 Da and a nearly baseline-resolved shift in reversed-phase LC retention time of +0.2 min. The dual coverage of both the non-glycosylated and deglycosylated peptides and their resolvability allows comparison (Figure 2B). Note that the signal for the non-glycosylated peptide is much lower than that of the de-glycosylated peptide, suggesting that the N162-nonglycosylated population of CD16a is of relatively low abundance compared to the N162-glycosylated population; consequently, the HDX experiment suffers high standard deviations. For the unbound state, the HDX for both the glycosylated and deglycosylated 153-166 peptide is similar, suggesting that the glycosylation does not affect the local structure. No statistically significant difference in HDX is observed for the glycosylated 153-166 peptide when CD16a is unbound vs. bound to IgG1. The 153-166 peptide, post-HDX deglycosylated, does show a statistically significant difference in deuterium uptake when CD16a is unbound vs. bound to IgG1. This binding-induced HDX difference is observed for another charge state of this peptide and for a longer peptide covering the same region (Figure 3B), further validating the influence of N162 glycosylation on IgG1 binding affinity.

Figure 2.

LC separation allows concurrent characterization of HDX differences for a deglycosylated peptide within the binding site and its nonglycosylated counterpart. (A) Extracted ion chromatogram for m/z 741.5 – 742.5 showing separation of the deglycosylated and nonglycosylated peptide fragment 153-166 (2+) (left), and corresponding mass spectra extracted at 5.2-5.35 min (purple) and 5.37-5.6 min (green) (right). The theoretical m/z for the nonglycosylated and deglycosylated peptide fragments 153-166 (2+) are 741.8721 and 742.3641, respectively. (B) HDX kinetic curves of the nonglycosylated (left) and deglycosylated (bottom) 153-166 (2+) peptide fragment from the CD16a binding site with IgG1, unbound (black) and bound to IgG1 (red). Error bars indicate the standard deviation for technical duplicates.

Figure 3.

Cumulative differences in HDX upon IgG1 binding clearly indicate binding-induced protection around N162 when using optimized post-HDX de-glycosylation. (A) Cumulative difference in HDX of unbound CD16a vs. IgG bound CD16a across all time points. The gray shaded region indicates the 98% confidence global significance limit for differential HDX. Statistically significant increases and decreases in HDX upon IgG binding are indicated as red and blue, respectively. HDX results for those peptides that were not glycosylated in the sample are faded. Stars indicate peptides covering N162. (B-C) Statistically significant increases (red) and decreases (red) in deuterium uptake as indicated in (A) are mapped onto the IgG-Fc (cyan and green)/CD16a (pink) complex structure (PDB 3SGJ), (B) and (C) show the results without deglycosylated peptides and with deglycosylated peptides, respectively. Glycans are shown as sticks. Regions with no coverage are shown in gray.

The benefit of post-HDX de-glycosylation of CD16a for characterizing its binding site with IgG1 is clearly shown in a peptide-level map of IgG1-induced HDX differences for nonglycosylated (Figure 3A) vs. post-HDX deglycosylated CD16a peptides (Figure 3B). The HDX differences for nonglycosylated peptides are consistent with those previously reported,22 with binding-induced changes in interdomain motion of CD16a,29–30 (successful crystal structure of the CD16a binding site requires an IgG-Fc truncation20–21) (Figure 3A inset). An increase in HDX is observed within the interlobe region of CD16a consistent with increased interdomain motion of CD16a induced by binding IgG (residues 9-16). Clear protection from HDX occurs within much of the binding site (residues 85-92 and 101-139). Lack of coverage around N162 without deglycosylation, however, clearly prevents HDX-MS characterization of the binding site. No other deglycosylated peptides show evidence of statistically significant binding-induced changes in HDX. The glycosylation state of N45 was reported to have an inhibitory effect on IgG-Fc binding related to steric hinderance;13, 26 therefore, it is reasonable that the backbone solvent accessibility near the N45 glycosylation site may not be affected. Overall, this post-HDX deglycosylation method can distinguish binding-induced differences in HDX both around and remote from glycosylation sites despite the extra sample manipulation and higher degree of back-exchange.

One drawback to this approach is that the protein is digested prior to analysis, and thus the results for the glycosylated protein are convolved with those of the nonglycosylated. Consequently, if the N162-nonglycosylated protein does in fact bind with lower affinity than its glycosylated counterpart, the HDX results for the other regions of the protein are mixed (i.e., the increased protection from deuterium incorporation of the N162 glycosylated protein is attenuated by the presence of the N162 nonglycosylated protein and vice versa). One means to circumvent this issue may be a top-down with an electron-based fragmentation; however, the heterogeneity of the intact glycosylated protein and incomplete fragmentation are likely limiting factors for this type of characterization. Ultimately, this approach presents the best method to date for HDX characterization of a highly glycosylated protein binding site where the glycosite is involved in binding.

CONCLUSIONS

We modified the Rand and coworkers23–24 approaches for post-HDX deglycosylation of highly glycosylated CD16a by using PNGase A and applied it to confirm the impact of N162 glycosylation on binding with the IgG1-Fc domain. The concurrent detection of nonglycosylated and post-HDX deglycosylated 153-166 peptide shows clear evidence that the glycan has limited effect on local protein structure but increases the binding affinity with IgG1. This approach is appropriate to binding determinations where a glycosylation site is involved; however, these results suggest that the conditions for post-HDX deglycosylation is glycoprotein dependent such that optimization of the protocol on a case-by-case basis is critical, as described in the Supporting Information. Although we used commercially synthesized CD16a, Roberts, et al.31 reported that CD16a (and other Fcγ receptors) glycosylation from primary human monocytes varies by donor. We posit that the PNGase A de-glycosylation efficiency is affected by glycan identity. Donor samples with different glycoforms may now be used to assess this conclusion and examine our approach’s applicability to “real-world” systems.

There are four other Fcγ receptors; of these, FcγRIa (CD64a) and FcγRIIIb (CD16b) have seven and six glycosylation sites, respectively, and both exhibit higher glyco-heterogeneity than CD16a and bind IgG-type antibodies.32 CD64 binding with IgG-Fc is similarly dependent on N-linked glycosylation.33 We have found no reports on the effect of CD16b glycosylation for IgG-Fc binding. Post-HDX deglycosylation presents an opportunity to characterize the effect of glycosylation of other Fcγ receptors’ binding with IgG-Fc, likely showing the utility of this approach for increasingly complex glycoproteins.

PERSPECTIVE

Structural mass spectrometry is evolving to be an important tool in biotechnology, and progress can be expedited by academic/industry collaboration. This article reports research in such a collaboration. One purpose of this and several other past projects is to test feasibility and demonstrate applicability of protein footprinting (e.g., HDX, FPOP) to structure problems confronting these industries in discovery, development, and quality control of protein therapeutics. Some of the resulting papers represent method development, as does this article; others report applications of protein methods.

The most extensive collaborations have been with Bristol-Myers Squibb34–38, followed by Genentech39–41, Pfizer42–43, Gilead44–45, Amgen46, and an earlier study with Eli Lilly47

The occasion of publishing this study as part of the special Focus makes it appropriate for me (MLG) to thank these several companies and their scientists for their encouragement and support, both scientific and financial.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, NIGMS Grant P41GM103422 and R24GM136766 and by Eli Lilly Research Award Program.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures for post-HDX deglycosylation, LC-MSMS mapping, LC-MS analyses, data processing, pepsin-coupled beads/PNGase A incubation optimization; all coverage maps for optimizing post-HDX deglycosylation incubation conditions; comparison of digestion products for different incubation conditions; peptide-level back-exchange for the optimized conditions; all kinetics plots for post-HDX deglycosylation of CD16a binding IgG1; averages and standard deviations for all HDX measurements (csv).

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Conflict of Interest:

MLG is unpaid member of scientific advisory board of Protein Metrics, a software company building applications in HDX and MS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ma B; Guan X; Li Y; Shang S; Li J; Tan Z, Protein Glycoengineering: An Approach for Improving Protein Properties. Frontiers in Chemistry 2020, 8 (622). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reily C; Stewart TJ; Renfrow MB; Novak J, Glycosylation in health and disease. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2019, 15 (6), 346–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varki A, Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2016, 27 (1), 3–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Läubli H; Borsig L, Altered Cell Adhesion and Glycosylation Promote Cancer Immune Suppression and Metastasis. Front. Immunol 2019, 10, 2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buffone A; Weaver VM, Don’t sugarcoat it: How glycocalyx composition influences cancer progression. J. Cell Biol 2020, 219 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houde D; Peng Y; Berkowitz SA; Engen JR, Post-translational Modifications Differentially Affect IgG1 Conformation and Receptor Binding. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2010, 9 (8), 1716–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara C; Stuart F; Sondermann P; Brunker P; Umana P, The carbohydrate at FcgammaRIIIa Asn-162. An element required for high affinity binding to non-fucosylated IgG glycoforms. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281 (8), 5032–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes JM; Frostell A; Karlsson R; Müller S; Martín SM; Pauers M; Reuss F; Cosgrave EF; Anneren C; Davey GP; Rudd PM, Identification of Fc Gamma Receptor Glycoforms That Produce Differential Binding Kinetics for Rituximab. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2017, 16 (10), 1770–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes JM; Frostell A; Cosgrave EFJ; Struwe WB; Potter O; Davey GP; Karlsson R; Anneren C; Rudd PM, Fc Gamma Receptor Glycosylation Modulates the Binding of IgG Glycoforms: A Requirement for Stable Antibody Interactions. J. Proteome Res 2014, 13 (12), 5471–5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudis CA, Trastuzumab — Mechanism of Action and Use in Clinical Practice. N. Engl. J. Med 2007, 357 (1), 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiner GJ, Rituximab: Mechanism of Action. Semin. Hematol 2010, 47 (2), 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subedi GP; Falconer DJ; Barb AW, Carbohydrate–Polypeptide Contacts in the Antibody Receptor CD16A Identified through Solution NMR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry 2017, 56 (25), 3174–3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson QM; Barb AW, A perspective on the structure and receptor binding properties of immunoglobulin G Fc. Biochemistry 2015, 54 (19), 2931–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weis DD, Hydrogen Exchange Mass Spectrometry of Proteins. John Wiley & Sons: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalmers MJ; Busby SA; Pascal BD; West GM; Griffin PR, Differential hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analysis of protein–ligand interactions. Expert Review of Proteomics 2011, 8 (1), 43–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters BT; Ricciuti A; Mayne L; Englander SW, Minimizing back exchange in the hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry experiment. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2012, 23 (12), 2132–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masson GR; Burke JE; Ahn NG; Anand GS; Borchers C; Brier S; Bou-Assaf GM; Engen JR; Englander SW; Faber J; Garlish R; Griffin PR; Gross ML; Guttman M; Hamuro Y; Heck AJR; Houde D; Iacob RE; Jørgensen TJD; Kaltashov IA; Klinman JP; Konermann L; Man P; Mayne L; Pascal BD; Reichmann D; Skehel M; Snijder J; Strutzenberg TS; Underbakke ES; Wagner C; Wales TE; Walters BT; Weis DD; Wilson DJ; Wintrode PL; Zhang Z; Zheng J; Schriemer DC; Rand KD, Recommendations for performing, interpreting and reporting hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments. Nature Methods 2019, 16 (7), 595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttman M; Scian M; Lee KK, Tracking Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange at Glycan Sites in Glycoproteins by Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2011, 83 (19), 7492–7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhne F; Bonnington L; Malik S; Thomann M; Avenal C; Cymer F; Wegele H; Reusch D; Mormann M; Bulau P, The Impact of Immunoglobulin G1 Fc Sialylation on Backbone Amide H/D Exchange. Antibodies 2019, 8 (49). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizushima T; Yagi H; Takemoto E; Shibata-Koyama M; Isoda Y; Iida S; Masuda K; Satoh M; Kato K, Structural basis for improved efficacy of therapeutic antibodies on defucosylation of their Fc glycans. Genes Cells 2011, 16 (11), 1071–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radaev S; Motyka S; Fridman W-H; Sautes-Fridman C; Sun PD, The Structure of a Human Type III Fcγ Receptor in Complex with Fc. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276 (19), 16469–16477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi L; Liu T; Gross ML; Huang Y, Recognition of Human IgG1 by Fcγ Receptors: Structural Insights from Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange and Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (8), 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen PF; Comamala G; Trelle MB; Madsen JB; Jørgensen TJD; Rand KD, Removal of N-Linked Glycosylations at Acidic pH by PNGase A Facilitates Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry Analysis of N-Linked Glycoproteins. Anal. Chem 2016, 88 (24), 12479–12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comamala G; Madsen JB; Voglmeir J; Du Y.-m.; Jensen PF; Østerlund E; Trelle MB; Jørgensen TJD; Rand KD, Deglycosylation by the acidic glycosidase PNGase H+ enables analysis of N-linked glycoproteins by Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeck A; Pohlentz G; Schlothauer T; Peter-Katalinić J; Regula JT, Cell Type-Specific and Site Directed N-Glycosylation Pattern of FcγRIIIa. J. Proteome Res 2011, 10 (7), 3031–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizushima T; Yagi H; Takemoto E; Shibata-Koyama M; Isoda Y; Iida S; Masuda K; Satoh M; Kato K, Structural basis for improved efficacy of therapeutic antibodies on defucosylation of their Fc glycans. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms 2011, 16 (11), 1071–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes JM; Frostell A; Cosgrave EF; Struwe WB; Potter O; Davey GP; Karlsson R; Anneren C; Rudd PM, Fc gamma receptor glycosylation modulates the binding of IgG glycoforms: a requirement for stable antibody interactions. J. Proteome Res 2014, 13 (12), 5471–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara C; Grau S; Jäger C; Sondermann P; Brünker P; Waldhauer I; Hennig M; Ruf A; Rufer AC; Stihle M; Umaña P; Benz J, Unique carbohydrate–carbohydrate interactions are required for high affinity binding between FcγRIII and antibodies lacking core fucose. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108 (31), 12669–12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yogo R; Yamaguchi Y; Watanabe H; Yagi H; Satoh T; Nakanishi M; Onitsuka M; Omasa T; Shimada M; Maruno T; Torisu T; Watanabe S; Higo D; Uchihashi T; Yanaka S; Uchiyama S; Kato K, The Fab portion of immunoglobulin G contributes to its binding to Fcγ receptor III. Sci. Rep 2019, 9 (1), 11957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sondermann P; Huber R; Oosthuizen V; Jacob U, The 3.2-Å crystal structure of the human IgG1 Fc fragment–FcγRIII complex. Nature 2000, 406 (6793), 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts JT; Patel KR; Barb AW, Site-specific N-glycan Analysis of Antibody-binding Fc γ Receptors from Primary Human Monocytes. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2020, 19 (2), 362–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosgrave EF; Struwe WB; Hayes JM; Harvey DJ; Wormald MR; Rudd PM, N-linked glycan structures of the human Fcgamma receptors produced in NS0 cells. J. Proteome Res 2013, 12 (8), 3721–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu J; Chu J; Zou Z; Hamacher NB; Rixon MW; Sun PD, Structure of FcγRI in complex with Fc reveals the importance of glycan recognition for high-affinity IgG binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112 (3), 833–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Y; Chen G; Wei H; Huang RY; Mo J; Rempel DL; Tymiak AA; Gross ML, Fast photochemical oxidation of proteins (FPOP) maps the epitope of EGFR binding to adnectin. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2014, 25 (12), 2084–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J; Wei H; Krystek SR; Bond D; Brender TM; Cohen D; Feiner J; Hamacher N; Harshman J; Huang RYC; Julien SH; Lin Z; Moore K; Mueller L; Noriega C; Sejwal P; Sheppard P; Stevens B; Chen G; Tymiak AA; Gross ML; Schneeweis LA, Mapping the Energetic Epitope of an Antibody/Interleukin-23 Interaction with Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange, Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins Mass Spectrometry, and Alanine Shave Mutagenesis. Analytical Chemistry 2017, 89 (4), 2250–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li KS; Chen G; Mo J; Huang RYC; Deyanova EG; Beno BR; O’Neil SR; Tymiak AA; Gross ML, Orthogonal Mass Spectrometry-Based Footprinting for Epitope Mapping and Structural Characterization: The IL-6 Receptor upon Binding of Protein Therapeutics. Analytical Chemistry 2017, 89 (14), 7742–7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li KS; Schaper Bergman ET; Beno BR; Huang RYC; Deyanova E; Chen G; Gross ML, Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange and Hydroxyl Radical Footprinting for Mapping Hydrophobic Interactions of Human Bromodomain with a Small Molecule Inhibitor. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2019, 30 (12), 2795–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang MM; Huang RYC; Beno BR; Deyanova EG; Li J; Chen G; Gross ML, Epitope and Paratope Mapping of PD-1/Nivolumab by Mass Spectrometry-Based Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange, Cross-linking, and Molecular Docking. Analytical Chemistry 2020, 92 (13), 9086–9094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y; Wecksler AT; Molina P; Deperalta G; Gross ML, Mapping the Binding Interface of VEGF and a Monoclonal Antibody Fab-1 Fragment with Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins (FPOP) and Mass Spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2017, 28 (5), 850–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y; Cui W; Wecksler AT; Zhang H; Molina P; Deperalta G; Gross ML, Native MS and ECD Characterization of a Fab–Antigen Complex May Facilitate Crystallization for X-ray Diffraction. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2016, 27 (7), 1139–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y; Rempel DL; Zhang H; Gross ML, An improved fast photochemical oxidation of proteins (FPOP) platform for protein therapeutics. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2015, 26 (3), 526–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones LM; Sperry JB; Carroll JA; Gross ML, Fast photochemical oxidation of proteins for epitope mapping. Analytical Chemistry 2011, 83 (20), 7657–7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones LM; Zhang H; Cui W; Kumar S; Sperry JB; Carroll JA; Gross ML, Complementary MS methods assist conformational characterization of antibodies with altered S-S bonding networks. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2013, 24 (6), 835–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramakrishnan D; Xing W; Beran RK; Chemuru S; Rohrs H; Niedziela-Majka A; Marchand B; Mehra U; Zábranský A; Doležal M; Hubálek M; Pichová I; Gross ML; Kwon HJ; Fletcher SP, Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Function Requires Zinc Binding. Journal of Virology 2019, 93 (16), e00250–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niu B; Appleby TC; Wang R; Morar M; Voight J; Villaseñor AG; Clancy S; Wise S; Belzile J-P; Papalia G; Wong M; Brendza KM; Lad L; Gross ML, Protein Footprinting and X-ray Crystallography Reveal the Interaction of PD-L1 and a Macrocyclic Peptide. Biochemistry 2020, 59 (4), 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J; Li J; Craig TA; Kumar R; Gross ML, Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry Reveals Calcium Binding Properties and Allosteric Regulation of Downstream Regulatory Element Antagonist Modulator (DREAM). Biochemistry 2017, 56 (28), 3523–3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi L; Liu T; Gross ML; Huang Y, Recognition of Human IgG1 by Fcgamma Receptors: Structural Insights from Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange and Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (8), 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.