Abstract

Carbon molecular sieve (CMS) membranes prepared by carbonization of polymers containing strongly size-sieving ultramicropores are attractive for high-temperature gas separations. However, polymers need to be carbonized at extremely high temperatures (900° to 1200°C) to achieve sub-3.3 Å ultramicroporous channels for H2/CO2 separation, which makes them brittle and impractical for industrial applications. Here, we demonstrate that polymers can be first doped with thermolabile cross-linkers before low-temperature carbonization to retain the polymer processability and achieve superior H2/CO2 separation properties. Specifically, polybenzimidazole (PBI) is cross-linked with pyrophosphoric acid (PPA) via H bonding and proton transfer before carbonization at ≤600°C. The synergistic PPA doping and subsequent carbonization of PBI increase H2 permeability from 27 to 140 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity from 15 to 58 at 150°C, superior to state-of-the-art polymeric materials and surpassing Robeson’s upper bound. This study provides a facile and effective way to tailor subnanopore size and porosity in CMS membranes with desirable molecular sieving ability.

Synergistic thermolabile cross-linking and low-temperature carbonization of polymers render superior H2/CO2 separation property.

INTRODUCTION

Porous nanostructured carbon materials with tunable pore structures, high surface area, and excellent physicochemical stability have attracted substantial interest for electrocatalysts, supercapacitors, adsorbents, and membranes for both liquid (1) and gas separations (2–9). For example, polymers with suitable microstructures can be pyrolyzed to obtain carbon molecular sieve (CMS) membranes with ultramicroporous channels and thus sharp molecule-sieving properties. However, the channel size is usually influenced by a complicated interplay of several factors, such as polymer precursors, pyrolysis temperatures and ramping procedures, and gas compositions (5, 10–12), and therefore, it remains elusive to obtain desirable subnanometer channels for targeted molecular separations. Here, we demonstrate an effective way to systematically manipulate the ultramicropore size and porosity for targeted separations, i.e., cross-linking polymer precursors with thermolabile cross-linkers followed by low-temperature pyrolysis of the cross-linkers.

Blue hydrogen is an important energy carrier for the transition to a carbon-neutral society, where H2 is produced using conventional reforming or gasification of fossil fuels while the by-product of CO2 is captured for utilization or sequestration. The separation of H2 from CO2 is a critical step for this process to be economically competitive (2, 13–16). Membrane technology has attracted notable interest because of its high energy efficiency, and the key is high-performance materials with high gas permeability to lower membrane areas and system costs and high selectivity to improve product purity (8, 17, 18). On the basis of the solution-diffusion model, gas permeability (PA) is expressed as: PA = SA × DA, where SA is the gas solubility, and DA is the gas diffusivity. Gas selectivity (αA/B) is the ratio of the permeability of the two gases and a combination of solubility selectivity (SA/SB) and diffusivity selectivity (DA/DB). CO2 with a critical temperature of 304 K is more condensable and thus has a higher solubility than H2 (33 K), and H2 with a kinetic diameter of 2.89 Å has higher diffusivity than CO2 (3.3 Å). Therefore, membrane materials should have a strong size-sieving ability and free volumes between 2.89 and 3.3 Å to maximize the H2/CO2 diffusivity selectivity (19).

Polybenzimidazole (PBI) is a leading material for H2/CO2 separation with H2 permeability of 27 Barrer [1 Barrer = 1 × 10−10 cm3 (standard temperature and pressure) cm cm−2 s−1 cmHg−1] and H2/CO2 selectivity of 15 at 150°C due to its strong size-sieving ability derived from hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking (14, 19–22). PBI was further cross-linked using terephthaloyl chloride (21), phosphoric acid (23, 24), and 1,3,5-tris(bromomethyl) benzene (TBB) (25), which decreased polymer-free volume and increased the size-sieving ability and thus H2/CO2 selectivity. However, the decreased free volume inevitably decreases the H2 permeability, which is also known as permeability/selectivity trade-off, a conundrum in developing high-performance membrane materials (17, 26).

Pyrolysis of polymers creates a bimodal pore size distribution in CMS membranes populated with microcavities (7 to 20 Å) that accelerates gas diffusion and ultramicropores (<7 Å) that confer strong size-sieving ability, thus improving permeability and selectivity simultaneously (8, 9). Conventional CMS membranes are often derived from polyimides and polymers of intrinsic microporosity, leading to ultramicropores of >3.3 Å, and thus they have been extensively explored for the separation, where at least one of the gases has a kinetic diameter greater than 3.3 Å, such as CO2/CH4 (12, 27–29), O2/N2 (30–32), and C2H4/C2H6 (33, 34). Increasing pyrolysis temperature tightens the packing of polymer chains, thus decreasing the sizes of both micropores and ultramicropores (35). To achieve high selectivity of those gas pairs, the pyrolysis temperature of CMS materials is usually 800°C or higher (27, 36, 37). However, few CMS membranes had been demonstrated for H2/CO2 separation because extremely high pyrolysis temperature is required to achieve ultramicropores of <3.3 Å to reject CO2 while retaining the high H2 permeability (19, 38–40). For example, pyrolysis of PBI at 700°C increased H2 permeability from 12 to 2400 Barrer but decreased H2/CO2 selectivity from 14 to 8.7 at 100°C; by contrast, increasing the pyrolysis temperature to 900°C increased the H2/CO2 selectivity to 80 but decreased H2 permeability to 33 Barrer. Kapton carbonized at around 1100°C exhibited an extremely high H2/CO2 selectivity of 343 with H2 permeability of only 0.32 Barrer at 50°C (40). Besides the low gas permeability and difficulty for industrial production scale-up, the high carbonization temperature inevitably makes the membrane brittle and causes the collapse of porous supports of industrial membranes (27, 41).

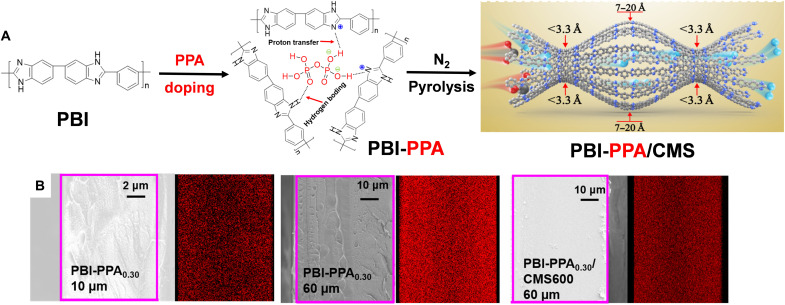

Here, we demonstrate that sub-3.3 Å ultramicropores required for H2/CO2 separation can be created in PBI by synergistic doping with pyrophosphoric acid (H4P2O7, PPA) and low-temperature pyrolysis, as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, PBI thin films are first doped by thermolabile PPA, which has four acidic protons and cross-links PBI chains via proton transfer and hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing size-sieving ability (23, 24). The doped PBIs are named as PBI-PPAx, where x is the doping level defined as the molar ratio of PPA to PBI repeating units in the films. The films are then carbonized at a temperature (TC, °C) under N2 to form CMS (42), which are denoted as PBI-PPAx/CMSTC. The successful doping can be validated by the presence of the phosphorous element in both pristine and carbonized films by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Moreover, PPA degrades at ≈200°C, much lower than PBI (≈600°C), creating sub-3.3 Å ultramicropores and microcavities at low TC and retaining excellent mechanical property of PBI and thus handleability of the CMS membranes.

Fig. 1. Approach of PPA cross-linking and carbonization to create right free volumes for H2/CO2 separation.

(A) Design principles of creating bimodal distribution of free volumes. (B) SEM images and in situ EDS mappings of phosphorus on the cross section of the PBI-PPA0.34 films before and after carbonization at 600°C. PPA, pyrophosphoric acid (H4P2O7).

We investigate the effects of PPA doping level and TC on physicochemical properties and H2/CO2 separation performance of PBI-PPA and PBI-PPA/CMS. TC was varied from 500° to 600°C, much lower than the conventional values of 900° to 1200°C, to retain good mechanical properties. PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 exhibits the best H2/CO2 separation properties among the samples evaluated and above Robeson’s upper bound. The sample was further challenged with simulated syngas containing water vapor for about 105 hours, demonstrating its stable performance and potential for industrial applications. Integration of doping with thermolabile cross-linkers and low-temperature carbonization provides an effective approach to designing stable porous materials with excellent processability for next-generation molecular sieving membranes.

RESULTS

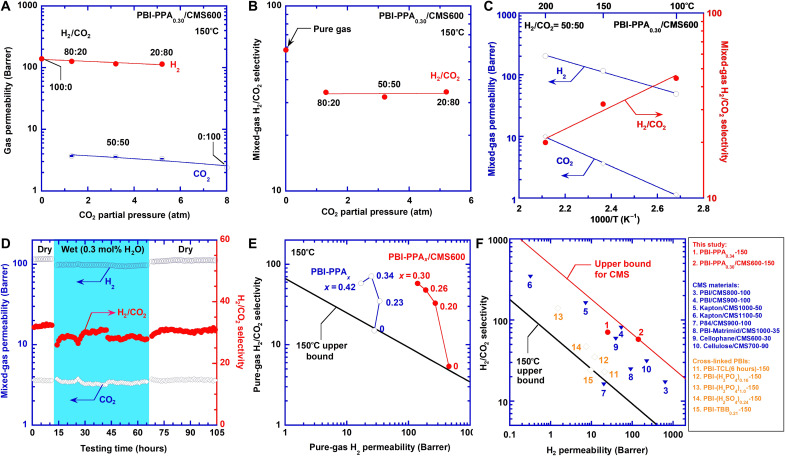

Superior H2/CO2 separation performance of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600

To highlight the potential of the CMS membranes, we first demonstrate the separation performance and stability of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 (with the best combination of pure-gas H2/CO2 separation properties) when challenged using simulated syngas containing water vapor. Figure 2A shows that both mixed-gas H2 and CO2 permeability slightly decrease with increasing CO2 partial pressure due to the competitive sorption, which is common in porous materials (4, 43). Consequently, it exhibits a substantial decrease from pure-gas H2/CO2 selectivity of 58 to mixed-gas H2/CO2 selectivity of 33 (Fig. 2B). However, mixed-gas H2/CO2 selectivity is independent of the CO2 partial pressure, indicating the absence of CO2 plasticization due to the low CO2 sorption at high temperatures. Figure 2C illustrates the effect of the temperature on mixed-gas permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity with H2:CO2 of 50:50 at 6.5 atm. On the other hand, mixed-gas H2/CO2 selectivity decreases with increasing temperature, presumably because of the weakened size-sieving ability at higher temperatures.

Fig. 2. Superior and stable H2/CO2 separation performance of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600.

(A) Mixed-gas H2 and CO2 permeability and (B) H2/CO2 selectivity at 6.5 atm and 150°C as a function of the feed CO2 partial pressure. (C) Effect of temperature on mixed-gas permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity with H2/CO2 of 50:50 at 6.5 atm. The lines are the best fits of Eq. 4. (D) Long-term stability in dry-wet-dry conditions with H2/CO2 of 50:50 at 6.5 atm and 150°C for 105 hours. (E) Pure-gas H2/CO2 separation performance of PBI-PPA and PBI-PPA/CMS600 at 150°C benchmarking with Robeson’s upper bound at 150°C. (F) Comparison on H2/CO2 separation properties among PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 and state-of-the-art materials, including CMS materials [including PBI/CMS800 (4), PBI/CMS900 (4), Kapton/CMS1000 (40), Kapton/CMS1100 (40), P84/CMS900 (39), PBI/Matrimid/CMS1000 (38), cellophane/CMS600 (44), and cellulose/CMS700 (2)] and cross-linked PBIs [PBI-TCL (6 hours) (21), PBI-(H3PO4)0.16 (24), PBI-(H3PO4)1.0 (24), PBI-(H2SO4)0.24 (24), and PBI-TBB0.21 (25)]. For CMSy-z, y and z represent TC and testing temperature (°C), respectively. For other materials, the values after the dash represent the testing temperature (°C). The details are also given in table S1.

Typical coal-derived syngas mainly contains ≈56% H2, ≈41% CO2, water vapor, and other minor components after the water-gas shift reaction. Hence, the long-term stability of the PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 film was investigated using wet and dry H2/CO2 mixture at 6.5 atm and 150°C. Specifically, a dry gas mixture of 50% H2/50% CO2 was initially introduced as the feed for 12 hours. Then, 0.3 mol % of water vapor was added for ≈54 hours, followed by switching back to the dry condition. As shown in Fig. 2D, both H2 permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity are stable at ≈110 Barrer and ≈31, respectively, indicating that PPA0.30/CMS600 is stable against physical aging or water vapor.

Figure 2E compares the pure-gas H2/CO2 separation performance of PBI-PPA and PBI-PPA/CMS600 at 150°C with Robeson’s upper bound (19). Both PBI and PBI/CMS600 show the separation performance near the upper bound, while the PBI-PPA and PBI-PPA/CMS600 demonstrate the separation properties above the upper bound. Particularly, PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 shows an excellent combination of H2 permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity, indicating their potential for high-temperature H2/CO2 separation.

Figure 2F compares PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 with leading membrane materials for H2/CO2 separation. The PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 displays excellent H2/CO2 separation performance compared with state-of-the-art polymers (21, 24, 25) and CMSs (2, 4, 38–40, 44). The PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 defines the new upper bound for H2/CO2 separation for CMS membranes, which is above the upper bound for conventional polymers. PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 also shows H2/CO2 separation properties comparable to inorganic materials (cf. fig. S1 and table S2), such as silica membranes with H2 permeability of 45 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of 71 at 200°C (13, 45), zeolitic membrane with H2 permeability of 45 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of 71 at 300°C (16), poly(triazine imide) nanosheets with H2 permeability of 180 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of 10 at 250°C (14), and graphene oxide membranes with H2 permeability of ≈200 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of ≈50 at 100°C (46). Moreover, with their low carbonization temperature, PBI-PPA0.30/CMS membranes can be seamlessly incorporated into manufacturing practices of polymer-based membranes for high-temperature H2/CO2 separation.

Tightening PBI nanostructures by PPA doping

To elucidate the structure and property relationship in the CMS samples, the effect of PPA doping on the physical properties is first investigated using PBI films with a thickness of 12 μm. Three doping levels (0.23, 0.34, and 0.42) in the films were obtained by varying the molar ratios of PPA in the doping solutions to the PBI repeating unit at 0.25, 0.5, to 1, respectively (fig. S2A). The doping time is set as nominally 72 hours, above which the doping level is invariant, as the reaction of PPA and PBI reaches equilibrium (fig. S2B). Figure S3A illustrates the strong interaction between PPA and PBI by the Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of PBI-PPA films. The characteristic peak at 910 cm−1 representing the P─O bonding indicates the existence of PPA (47). After the proton transfer from PPA to PBI, PPA evolves into H3P2O7− and H2P2O72− functionalities, confirmed by the new PO2 peak at 1050 cm−1 (24). The characteristic peaks at 870 and 945 cm−1 for P(OH)2 are somewhat diminished in intensity in the spectra of PBI-PPA, indicating the loss of protons in PPA due to hydrogen bonding and proton transfer with PBI.

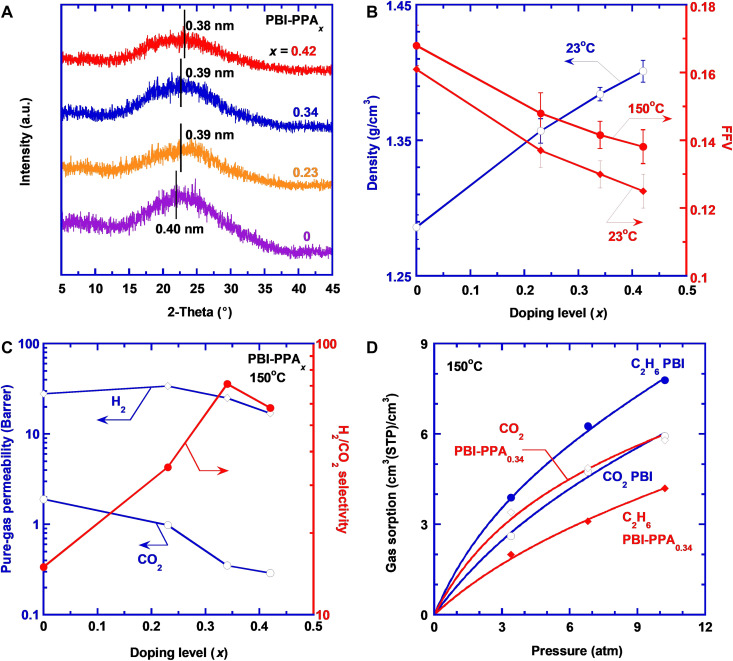

Figure 3A displays the effect of PPA doping on wide-angle x-ray diffraction (WXRD) patterns of PBI-PPA films. The pure PBI shows a broad peak at 22.4°, corresponding to a d-spacing (representing an average intersegmental distance between polymer chains) of nominally 0.40 nm calculated using Bragg’s equation (48). Increasing the doping level decreases the d-spacing to 0.38 nm, indicating the tightened nanostructures and enhanced size-sieving ability after the cross-linking.

Fig. 3. Effect of PPA doping on physicochemical and gas transport properties of the PBI.

(A) WXRD patterns, (B) density at 23°C and FFV at 23° and 150°C, and (C) pure-gas H2/CO2 separation properties; (D) CO2 and C2H6 sorption isotherms of PBI and PBI-PPA0.34. The curves are the best fits of Eq. 2 with the values of the adjustable parameters recorded in table S5. a.u., arbitrary units.

Figure 3B shows that the density of the PBI-PPA films increases with increasing doping level and can be satisfactorily described using an additive model (cf. eq. S2 and fig. S3B). The modeled density of PPA in the films is 2.25 g/cm3, higher than the density of pure PPA (2.0 g/cm3), confirming the strong interaction between PPA and PBI chains. The fractional free volume (FFV) of the PBI-PPAx films can be estimated using the following equation

| (1) |

where ρb is the bulk density, and V and Vw are the specific volume and van der Waals volume, respectively. Vw can be estimated by the group contribution method (cf. table S3). Figure 3B shows that FFV decreases from 0.161 to 0.125 as the doping level increases from 0 to 0.42 at 23°C because of the cross-linking, consistent with that from positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS). PBI-PPA0.30 displays a lower ortho-positronium “pick-off” lifetime (τ3) and intensity (I3), which indicates a lower nanoscale pore radius and their corresponding number density within the samples, thereby denoting lower free volume in PBI-PPA0.30 than PBI (table S4). Figure 3B also shows that the FFV increases with increasing temperature due to the thermal expansion (table S3).

Figure 3C presents pure-gas H2 and CO2 permeability of PBI-PPA films at 150°C and 11 atm. As the doping level increases from 0 to 0.34, CO2 permeability decreases sharply from 2.0 to 0.30 Barrer, and H2 permeability decreases slightly, leading to a dramatic increase of H2/CO2 selectivity from 15 to 71. However, a further increase of the doping level to 0.42 decreases H2/CO2 selectivity, presumably because the excessive PPA plasticizes PBI and decreases the size-sieving ability of the composition (24).

To elucidate the gas transport mechanism, gas permeability is decoupled into solubility and diffusivity. Figure 3D shows sorption isotherms (gas sorption of CA versus equilibrium pressure of pA) of CO2 and C2H6 in PBI and PBI-PPA0.34 at 150°C. As H2 sorption is too low to measure accurately using our apparatus, C2H6 is used as a surrogate for H2 because both H2 and C2H6 are nonpolar and lack the quadrupole moment to have specific interactions with PBI or PPA. In addition, C2H6 has a critical temperature of 305 K, similar to CO2 (304 K), indicating similar condensability. As shown in Fig. 3E, the isotherms can be satisfactorily described by the dual-mode sorption model (3, 18)

| (2) |

where kD is the Henry’s constant, C′H is the Langmuir sorption capacity, and b is the affinity parameter. The values of these parameters are recorded in table S5.

PBI and PBI-PPA0.34 show similar CO2 sorption, indicating that the PPA doping has a negligible effect on CO2 sorption, and thus, the decrease in CO2 permeability by the doping can be ascribed to the decreased gas diffusivity. C2H6 sorption decreases considerably after the doping, reflecting that the decreased FFV has more impact on the sorption of larger molecules like C2H6 (with a kinetic diameter of 4.1 Å) than CO2. Figure S3C shows that both H2 and CO2 permeability can be described using the free volume model with the BA value of 0.28 for H2 and 1.5 for CO2, consistent with the larger molecular size of CO2.

Effect of doping level on physical properties of PBI-PPA/CMS600

To obtain freestanding CMS films with good mechanical stability, PBI-PPA precursors were prepared using PBI films with a thickness of 50 to 70 μm. PPA doping was conducted under 60°C to accelerate PPA diffusion and shorten the doping time to about 168 hours (fig. S2B). Three different doping levels (0.20, 0.26, and 0.30) in the films were obtained by varying the molar ratios of PPA in the doping solutions to the PBI repeating unit at 0.25, 0.38, and 0.5, respectively. The thicker films show lower doping levels at the same molar ratios due to the diffusion limitation of PPA in the samples, while higher doping temperatures reduce bonding between PPA and PBI. However, H2/CO2 separation properties of the thin and thick PBI-PPA films are similar. For example, thick films of PBI-PPA0.30 display H2 permeability of 26 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of 63 at 150°C, similar to those of thin films of PBI-PPA0.34 (25 Barrer and 71, respectively). Therefore, thin films can be considered as a surrogate for thick films. Figure 1B shows that the distribution of phosphorus (P) in PBI-PPA0.30 has little change after the carbonization, indicating that the degraded PPA still exists in CMS films, which is also confirmed by the molar ratio of N/C and P/C derived from EDS, as shown in table S6.

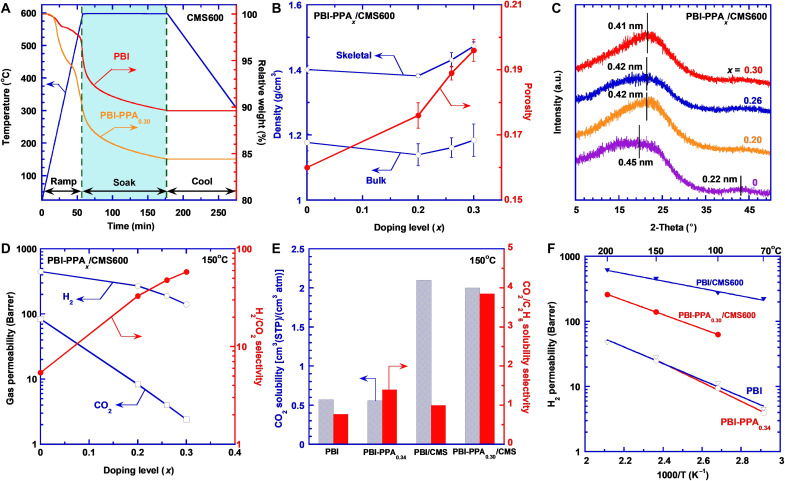

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) curves in Fig. 4A display the evolution from PBI to PBI/CMS600 and from PBI-PPA0.30 to PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600. The mass loss mainly happens at the ramping and soaking steps. PBI displays a mass loss of about 4% during the ramping (cf. fig. S4). By contrast, PBI-PPA0.30 experiences an approximate 10% mass loss during the ramping, mainly because of the PPA degradation. During the soaking period, both polymers exhibit similar mass loss, leading to a total mass loss of 10% for PBI/CMS600 and 16% for PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600. Figure S5A displays their FTIR spectra and the disappearing of the peaks of the amino-functional groups (4, 28). Table S6 also shows that the N/C ratio of PBI-PPA0.30 decreases after the carbonization [similar to the PBI (4)], indicating the loss of the N groups. A mass loss of ~10% for the PBI also indicates a notable formation of carbon structures, and therefore, these pyrolyzed materials are named as CMS materials (4, 28), as PBI has a carbon content of 78 mass%, and CMS materials are often defined as the pyrolyzed polymers with a carbon element content greater than 80 mass% (42).

Fig. 4. Effect of PPA doping on the properties of the carbonized PBI.

(A) Thermal degradation behavior. (B) Skeletal density, bulk density, and porosity. (C) WXRD patterns. (D) Pure-gas H2/CO2 separation properties at 150°C and 11 atm. (E) CO2 solubility and CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity at 150°C and 11 atm. Effect of temperature on (F) pure-gas H2 permeability. The lines are the best fits of Eq. 4.

Figure 4B shows that both ρb and skeletal density (ρs) of the CMS films decrease before increasing with the doping level because of the two opposite effects caused by the carbonization, i.e., the mass loss and volume shrinkage. Below the doping level of 0.2, the mass loss dominates and thus decreases ρb. By contrast, at higher doping levels, the film shrinkage dominates and thus increases ρb. The average porosity (ε) of the CMS films can be estimated using the following equation (4)

| (3) |

Figure 4B shows that ε increases with increasing doping level, consistent with the increased mass loss (fig. S5B). Figure S5C depicts the Raman spectra of the PBI-PPA/CMS600. The D peak at 1341 cm−1 and the G peak at 1580 cm−1 reflect the formation of disordered carbon and highly oriented graphitic carbon, confirming the successful carbonization of PBI-PPA/CMS600 (4). Increasing the doping level has a negligible effect on the area of the G peak and increases the area of the D peak before decreasing.

Figure 4C shows the effect of the PPA doping and carbonization on the d-spacing. Carbonization of PBI increases the d-spacing from 0.40 nm (Fig. 3D) to 0.45 nm. By contrast, the PPA doping decreases the d-spacing. For example, as the doping level increases from 0 to 0.30, the d-spacing of the CMS films decreases from 0.45 to 0.41 nm. As the ε values increase with increasing doping levels, the doping appears to decrease the size of free volume elements but increase the amount of the free volume elements, which can be beneficial to increase both size-sieving ability and gas permeability. The porosity evolution by carbonization was also detected using PALS (cf. fig. S5D and table S4). As PBI/CMS600 and PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 are conductive, their orthopositroniums are inhibited, and τ3 and I3 could not be obtained (4). Therefore, we used τ2 (for free annihilation of the positron and an electron) and its distribution (σ2) to estimate free-volume pores in those two CMS materials. PBI-PPA0.30–derived CMS films exhibit lower τ2 values than PBI/CMS600, consistent with the decreased d-spacing due to the PPA doping. The σ2 in PBI and PBI-PPA0.3 are larger than their CMS films, suggesting that the carbonization process creates a more homogeneous distribution of ultramicropores. In addition, PPA doping reduces the lifetime distribution, which is also consistent with the Raman result.

Mechanical properties of PBI/CMS600 and PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 films were determined using a three-point flexural test (cf. fig. S5, E to H, and table S7). Both acid doping and carbonization increase Young’s modulus but lower the break strain, indicating a ductile-to-brittle transition. PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 has a higher Young’s modulus but lower break strain than PBI/CMS600, indicating that the PPA doping induces rigid and stiff structure during the carbonization. In addition, all CMS films have lower Young’s modulus than amorphous carbon films, reflecting the porous structure and incomplete carbonization of these CMS films (49). Table S8 summarizes mechanical properties of the PBI-based films and CMS membranes for H2/CO2 separation reported in the literature (2, 20, 50, 51). The PBI-PPA0.30/CMS films display comparable mechanical properties.

Pure-gas H2 and CO2 permeability of PBI-PPA/CMS600 were measured at 150°C, as shown in Fig. 4D. Increasing the PPA doping level decreases gas permeability and increases H2/CO2 selectivity, indicating that the improved size-sieving ability by cross-linking is preserved after the carbonization, consistent with the decreased d-spacing (Fig. 4C) and decreased heterogeneity of structure (fig. S5D). Carbonization of the PBI-PPA increases gas permeability and retains high H2/CO2 selectivity. For example, PBI-PPA0.23 exhibits H2 permeability of 34 Barrer and H2/CO2 selectivity of 35 at 150°C, while the PBI-PPA0.20/CMS600 shows a much higher H2 permeability of 270 Barrer and a similar H2/CO2 selectivity of 33. The carbonization creates the cavities (consistent with the higher ε values) while retaining the ultramicroporous channels for molecular sieving.

Figure 4E illustrates the effect of carbonization on CO2 solubility and CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity at 150°C and 11 atm for PBI and PBI-PPA0.34. Carbonization increases the CO2 solubility by almost three times for both samples because of the increased porosity and values (cf. table S5). Carbonization also increases the CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity, which can be ascribed to the generation of polar C─N bonding with a strong affinity toward CO2 (52), as evidenced by the increased b values after the carbonization (table S5). For example, PBI and PBI/CMS exhibit CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity of 0.77 and 1.0, respectively. The carbonization of PBI-PPA0.30 increases CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity from 1.4 to 3.9 because of the decreased free volume size in the CMS, which restricts the absorption of the larger C2H6 molecule. The carbonization creates more microchannels and a more homogeneous ultramicroporous structure (lower σ2 values) that is accessible for gas transport despite reductions in average pore size as evidenced by PALS and WXRD.

Figure 4F compares the effect of temperature on pure-gas H2 permeability of PBI, PBI-PPA0.34, PBI/CMS600, and PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600. H2 permeability can be satisfactorily described using the Arrhenius equation (4)

| (4) |

where P0,A is a pre-exponential factor, EP,A is the activation energy of the permeation, R is the gas constant, and T is the testing temperature. The fitted values of P0,A and EP,A are recorded in table S9. PBI-PPA0.34 has a higher EP,A value (28 kJ/mol) for H2 than PBI (24 kJ/mol) due to the decreased FFV and enhanced size-sieving ability. The carbonization decreases the EP,A values for H2 because of the increased porosity and amount of free volume elements. For example, the EP,A value for H2 decreases by more than 50% from 24 kJ/mol for PBI to 11 kJ/mol for PBI/CMS. Table S9 also shows that mixed-gas H2 permeability can be described using Eq. 4. The EP,A value is similar to that for the pure gas, but the P0,A value is lower than the pure gas because of the competitive sorption with CO2.

Figure S6A displays that CO2 permeability can be satisfactorily described using the Arrhenius equation, and EP,A values of CO2 follow the trend similar to those for H2. Consequently, PBI, PBI/CMS600, and PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 exhibit the H2/CO2 selectivity independent of the temperature (fig. S6B). However, the selectivity of PBI-PPA0.34 decreases with increasing temperature, presumably due to the weakened PBI cross-linking at elevated temperatures. Figure S6C presents the CO2 diffusivity at various temperatures, which is satisfactorily fitted using the Arrhenius equation. The activation energy for the diffusion (ED,A) is recorded in table S10. The ED,A values exhibit a trend similar to EP,A, consistent with the predominant effect on the gas diffusivity (instead of solubility) induced by the PPA doping and carbonization.

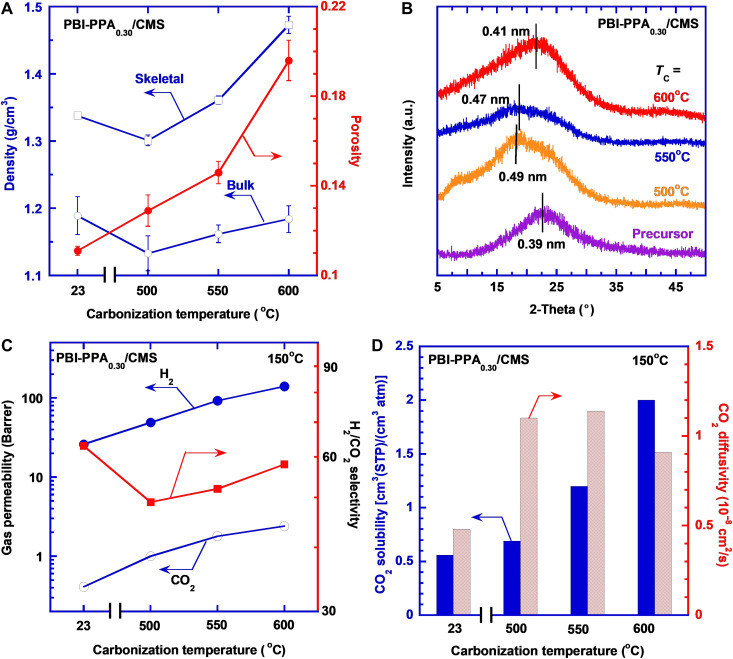

Effect of carbonization temperature on physical properties of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS

PBI-PPA0.30/CMS600 has the highest H2/CO2 selectivity among the CMS600 samples, and thus, PBI-PPA0.30 was chosen to investigate the effect of TC values on the H2/CO2 separation properties. Figure 5A shows that increasing TC values increases both ρb and ρs, indicating a tighter packing of polymer chains, consistent with the decreased d-spacing (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, the ε value dramatically increases with increasing TC, consistent with the increased mass loss (fig. S7A), suggesting the formation of large cavities. PBI/CMS shows the same trend of increasing ρb, ρs, and ε values and decreasing d-spacing with increasing TC (fig. S7, B and C). In general, carbonization at any TC increases the d-spacing compared with their respective polymer precursors.

Fig. 5. Effect of carbonization temperature on physical and gas separation properties of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS.

(A) Skeletal density, bulk density, and porosity; (B) WXRD patterns; (C) pure-gas H2 and CO2 permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity; (D) CO2 solubility and diffusivity at 150°C and 11 atm.

Figure 5C presents pure-gas permeability and H2/CO2 selectivity at 150°C for PBI-PPA0.30/CMS prepared at different TC values. As expected, increasing TC value increases gas permeability because of the increased porosity and the amounts of free volume elements. For example, as the TC increases from 500° to 600°C, H2 permeability increases from 49 to 140 Barrer for PBI-PPA0.30/CMS and from 69 to 450 Barrer for PBI/CMS (fig. S7D). Increasing the TC values decreases the H2/CO2 selectivity for PBI/CMS due to the creation of microcavities that allow increased transport of CO2 (fig. S7D) (4). By contrast, the H2/CO2 selectivity increases with increasing the TC value for PBI-PPA0.30/CMS. The PPA doping decreases the free volume size (as confirmed by the WXRD patterns in Fig. 5B) and creates homogeneous pore structures (fig. S5D) that increase their size-sieving ability.

The effect of the TC values on the CO2 solubility and diffusivity of PBI-PPA0.30/CMS is exhibited in Fig. 5D. The sorption isotherms are shown in fig. S8 (A and B). CO2 solubility increases with increasing TC, mainly due to the physisorption based on the increased porosity. By contrast, CO2 diffusivity increases with TC before decreasing due to the interplay between increased porosity and decreased d-spacing, where the porosity has a greater effect on diffusivity at lower Tc, and the decreased d-spacing and skeletal density impose greater diffusivity restrictions at higher Tc. Figure S8C shows that C2H6 solubility increases with increasing TC due to the increased porosity. CO2/C2H6 solubility selectivity also increases with increasing TC owing to the formation of the CO2-philic C─N bonding sites and small free volume elements that are more accessible to smaller CO2 than C2H6.

DISCUSSION

We report an approach for sequential cross-linking and carbonization to synthesize CMS membranes with ultramicroporous channels less than 3.3 Å but more free volumes that enable both superior H2/CO2 selectivity and high permeability, along with excellent processability due to the reduced carbonization temperatures. Specifically, PBI containing amine groups is facilely cross-linked by PPA and then carbonized at <600°C. Increasing the PPA doping level decreases the d-spacing and free volume, while increasing the TC increases the porosity and decreases the d-spacing, thereby resulting in bimodal free volumes comprising sub-3.3 Å ultramicropores and >7-Å microcavities that improve the membrane performance. As the TC increases from 500° to 600°C, H2/CO2 selectivity decreases for PBI/CMS but increases for PBI-PPA/CMS. When challenged with simulated syngas streams, the PBI-PPA/CMS membranes exhibit superior H2/CO2 separation properties, surpassing Robeson’s upper bound and validating its potential for practical applications. Future work will focus on the fabrication of the hollow fiber membranes based on the acid-doped PBI followed by the carbonization to move the technology to the next level. Our approach opens up a new venue to design and synthesize porous carbon materials with controlled morphology and ease of processability for a variety of applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of PBI-PPA thin films

The reported solution casting method was used to prepare PBI thin films (23, 24). Shortly, the PBI solution was cast on a glass plate with a clearance of 100 μm. Then, the film was dried at around 60°C under a N2 flow for about 12 hours and then at around 200°C under vacuum for about 48 hours. After that, the film was immersed in methanol at ≈23°C with a stirring speed of approximately 60 rpm for about 24 hours. Last, the film was dried at nominally 100°C under a vacuum to remove absorbed methanol. The films have a uniform thickness of ≈12 μm.

PBI-PPA films were prepared by a solid-state doping method. Specifically, about 120 mg of PBI films were immersed in approximately 100 ml of methanol containing a desired amount of PPA at room temperature. The solution was stirred for about 72 hours to enable the reaction of PPA and PBI. To obtain different doping levels, the molar ratio of PPA to PBI repeating units in the solutions was varied from 0.25 to 1. Last, the doped films were dried in a vacuum oven at around 100°C for approximately 12 hours. The doping level (x) of the PPA in PBI can be determined using the following equation

| (5) |

where m0 and m1 are the mass of the film before and after the doping, respectively. The mass was determined with an analytical balance with a resolution of 0.1 mg. Macid and MPBI are the molar mass of the PPA (178 g mol−1) and PBI repeating unit (308 g mol−1), respectively.

Preparation of CMS films

To prepare CMS films, thick films of PBI-PPA (50 to 70 μm) were first prepared using the solution casting method with procedures similar to thin films, except the doping conditions that was modified to 60°C under reflux for approximately 168 hours. Next, the obtained films were sandwiched between two ceramic plates and left in the center of a 5-inch-diameter tube furnace (MTI Corporation, Richmond, CA) with a N2 flow of 200 ml/min. The temperature was then ramped up from ≈23°C to TC at 10°C/min, and the films were soaked for 2 hours. Last, the furnace was allowed to naturally cool down to ≈23°C under a N2 flow. The mass of each sample was recorded before and after the carbonization to calculate the weight loss.

Characterization of the PBI-PPA and CMS films

FTIR spectroscopy was conducted between wavenumbers of 450 to 2000 cm−1 using a vertex 70 Burker spectrometer (Billerica, MA). Thermal properties of the samples under N2 atmosphere were investigated using an SDT Q600 TGA (TA Instruments, DE). The temperature was then ramped up from room temperature to 800°C at 10°C/min. A Rigaku Ultima IV x-ray diffractometer was used to obtain WXRD patterns of samples. The wavelength of Cu Kα x-ray source is 1.54 Å. Raman spectra of CMS600 samples were obtained using a Renishaw inVia Raman Microscope (Renishaw plc, UK). No peaks were observed in CMS550, CMS500, and uncarbonized samples. The surface and cross section of the samples were imaged using a focused ion beam SEM (Carl Zeiss Auriga CrossBeam, Carl Zeiss Germany). In situ elemental analysis was performed using an EDS (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). All samples were coated with gold before the characterization. An analytical balance with a density kit (XS 64, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH) was used to measure densities of PBI-PPA thin films based on Archimedes’ principle (21). The bulk density of the CMS film was calculated on the basis of corresponded mass and volume. The skeletal density of the CMS films was measured using a Micromeritics Accu-Pyc II 1340 Gas Pycnometer (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA). The density of pure PPA was also measured using this Pycnometer. PALS measurements are used to estimate the size of ultramicropores or nanoscale structural porosity and their respective concentration in the samples. For each specimen, PALS measurements were conducted on two sets of sample films having lateral dimensions of about 10 mm2 and a nominal thickness of about 1 mm by stacking these films at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. The mechanical properties of PBI, PBI-PPA0.30, PBI/CMS500, and PBI/CMS550 were determined at 150°C using static tensile loading with a dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA, Q800 TA Instrument). Uniaxial tensile loading on the sample stripes (20 mm by 3 mm) was carried out with an initial strain of 0.1% at a constant strain rate of 1.0%/min till the sample fractured. The Young’s modulus of the samples was determined from the elastic deformation region of the stress-strain curve (which typically occurs within 1.0% strain). The tensile strength and fracture strain of samples were also determined according to the stress-strain curve. The mechanical properties of PBI, PBI-PPA0.30, PBI/CMS, and PBI-PPA0.30/CMS samples were further determined using a three-point flexural test with a DMA (RSA G2 TA Instrument). All tests were conducted at 23°C. The bending of the sample stripes was carried out by placing sample on the supporting pins, which are 10 mm apart, and bringing the middle portion of sample in direct contact with the loading pin moving at 0.01 mm/min. The tests were terminated as the loading pin head reached the maximum gap change of 2.0 mm.

A constant-volume and variable-pressure system was used to measure pure-gas permeability at various temperatures (21, 48). A constant-pressure and variable-volume apparatus was used to determine the mixed-gas permeability of H2/CO2 mixture (21). N2 was used as the sweep gas on the permeate. By passing the mixed gas through a water bubbler at ≈25°C, water vaper was introduced in the permeation cell. A gravimetric sorption analyzer (IGA 001, Hiden Isochema, UK) was used to determine the gas solubility of the sample at 150°C with the buoyancy effect considered (21, 48).

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Paulter Jr., A. L. Forster, and C. M. Stafford from NIST for careful review and suggestions toward the interpretation of the PALS data and other aspects of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) award no. DE-FE0031636 and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grant number 1804996. A.K. acknowledges financial assistance from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (award 70NANB18H226).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: L.H. and H.L. Methodology: L.H., V.T.B., A.K., S.F., W.G., S.P., X.C., G.Z., and Y.D. Investigation: L.H. and H.L. Visualization: L.H., H.L., and A.K. Supervision: H.L. Writing—original draft: L.H. Writing—review and editing: L.H., V.T.B., A.K., S.F., W.G., S.P., X.C., G.Z., Y.D., R.P.S., M.L., and H.L.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S8

Tables S1 to S10

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Koh D. Y., McCool B. A., Deckman H. W., Lively R. P., Reverse osmosis molecular differentiation of organic liquids using carbon molecular sieve membranes. Science 353, 804–807 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei L., Pan F., Lindbråthen A., Zhang X., Hillestad M., Nie Y., Bai L., He X., Guiver M. D., Carbon hollow fiber membranes for a molecular sieve with precise-cutoff ultramicropores for superior hydrogen separation. Nat. Commun. 12, 268 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanyal O., Hays S. S., León N. E., Guta Y. A., Itta A. K., Lively R. P., Koros W. J., A self-consistent model for sorption and transport in polyimide-derived carbon molecular sieve gas separation membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 20343–20347 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omidvar M., Nguyen H., Liang Huang, Doherty C. M., Hill A. J., Stafford C. M., Feng X., Swihart M. T., Lin H., Unexpectedly strong size-sieving ability in carbonized polybenzimidazole for membrane H2/CO2 separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 47365–47372 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y., Jue M. L., Zhang F., Mathias R., Jang H. Y., Lively R. P., Creation of well-defined “mid-sized” micropores in carbon molecular sieve membranes. Angew. Int. Ed. Chem. 131, 13393–13399 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J., He G., Huang S., Villalobos L. F., Dakhchoune M., Bassas H., Agrawal K. V., Etching gas-sieving nanopores in single-layer graphene with an angstrom precision for high-performance gas mixture separation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav1851 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shan M., Liu X., Wang X., Yarulina I., Seoane B., Kapteijn F., Gascon J., Facile manufacture of porous organic framework membranes for precombustion CO2 capture. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau1698 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koros W. J., Zhang C., Materials for next-generation molecularly selective synthetic membranes. Nat. Mater. 16, 289–297 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park H., Jung C. H., Lee Y. M., Hill A. J., Pas S. J., Mudie S. T., Van Wagner E., Freeman B. D., Cookson D. J., Polymers with cavities tuned for fast selective transport of small molecules and ions. Science 318, 254–258 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanyal O., Zhang C., Wenz G. B., Fu S., Bhuwania N., Xu L., Rungta M., Koros W. J., Next generation membranes -using tailored carbon. Carbon 127, 688–698 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S., Lee Y. M., Rigid and microporous polymers for gas separation membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 43, 1–32 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiyono M., Williams P. J., Koros W. J., Effect of pyrolysis atmosphere on separation performance of carbon molecular sieve membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 359, 2–10 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu L. X., Huang L., Venna S. R., Blevins A. K., Ding Y., Hopkinson D. P., Swihart M. T., Lin H., Scalable polymeric few-nanometer organosilica membranes with hydrothermal stability for selective hydrogen. ACS Nano 15, 12119–12128 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villalobos L. F., Vahdat M. T., Dakhchoune M., Nadizadeh Z., Mensi M., Oveisi E., Campi D., Marzari N., Agrawal K. V., Large-scale synthesis of crystalline g-C3N4 nanosheets and high-temperature H2 sieving from assembled films. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9851 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu L., Yin D., Qin Y., Konda S., Zhang S., Zhu A., Liu S., Xu T., Swihart M. T., Lin H., Sorption-enhanced mixed matrix membranes with facilitated hydrogen transport for hydrogen purification and CO2 capture. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904357 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dakhchoune M., Villalobos L. F., Semino R., Liu L., Rezaei M., Schouwink P., Avalos C. E., Baade P., Wood V., Han Y., Ceriotti M., Agrawal K. V., Gas-sieving zeolitic membranes fabricated by condensation of precursor nanosheets. Nat. Mater. 20, 362–369 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park H., Kamcev J., Robeson L. M., Elimelech M., Freeman B. D., Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galizia M., Chi W. S., Smith Z. P., Merkel T. C., Baker R. W., Freeman B. D., 50th Anniversary perspective: Polymers and mixed matrix membranes for gas and vapor separation: A review and prospective opportunities. Macromolecules 50, 7809–7843 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L., Pal S., Nguyen H., Bui V., Lin H., Molecularly engineering polymeric membranes for H2/CO2 separation at 100–300 °C. J. Polym. Sci. 58, 2467–2481 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon J. D., Bridge A. T., D’Ambra C., Freeman B. D., Paul D. R., Gas separation properties of polybenzimidazole/thermally-rearranged polymer blends. J. Membr. Sci. 582, 182–193 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu L., Swihart M., Lin H., Tightening polybenzimidazole (PBI) nanostructure via chemical cross-linking for membrane H2/CO2 separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 19914–19923 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Singh R. P., Dudeck K. W., Berchtold K. A., Benicewicz B. C., Influence of polybenzimidazole main chain structure on H2/CO2 separation at elevated temperatures. J. Membr. Sci. 461, 59–68 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu L., Bui V. T., Huang L., Singh R. P., Lin H., Facilely cross-linking polybenzimidazole with polycarboxylic acids to improve H2/CO2 separation performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 12521–12530 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu L., Swihart M., Lin H., Unprecedented size-sieving ability in polybenzimidazole doped with polyprotic acids for membrane H2/CO2 separation. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 94–100 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naderi A., Tashvigh A. A., Chung T. S., H2/CO2 separation enhancement via chemical modification of polybenzimidazole nanostructure. J. Membr. Sci. 572, 343–349 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H., Yavari M., Upper bound of polymeric membranes for mixed-gas CO2/CH4 separations. J. Membr. Sci. 475, 101–109 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y., Zhang K., Sanyal O., Koros W. J., Carbon molecular sieve membrane preparation by economical coating and pyrolysis of porous polymer hollow fibers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 12149–12153 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiao W., Ban Y., Shi Z., Jiang X., Li Y., Yang W., Gas separation performance of supported carbon molecular sieve membranes based on soluble polybenzimidazole. J. Membr. Sci. 533, 1–10 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Y., Chung T. S., Grafting thermally labile molecules on cross-linkable polyimide to design membrane materials for natural gas purification and CO2 capture. Energ. Environ. Sci. 4, 201–208 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu C.-P., Polintan C. K., Tayo L. L., Chou S.-C., Tsai H.-A., Hung W.-S., Hu C.-C., Lee K.-R., Lai J.-Y., The gas separation performance adjustment of carbon molecular sieve membrane depending on the chain rigidity and free volume characteristic of the polymeric precursor. Carbon 143, 343–351 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang C., Koros W. J., Ultraselective carbon molecular sieve membranes with tailored synergistic sorption selective properties. Adv. Mater. 29, 170163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park H. B., Lee Y. M., Fabrication and characterization of nanoporous carbon/silica membranes. Adv. Mater. 17, 477–483 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams J. S., Itta A. K., Zhang C., Wenz G. B., Sanyal O., Koros W. J., New insights into structural evolution in carbon molecular sieve membranes during pyrolysis. Carbon 141, 238–246 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salinas O., Ma X., Wang Y., Han Y., Pinnau I., Carbon molecular sieve membrane from a microporous spirobisindane-based polyimide precursor with enhanced ethylene/ethane mixed-gas selectivity. RSC Adv. 7, 3265–3272 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu S., Wenz G. B., Sanders E. S., Kulkarni S. S., Qiu W., Ma C., Koros W. J., Effects of pyrolysis conditions on gas separation properties of 6FDA/DETDA: DABA (3: 2) derived carbon molecular sieve membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 520, 699–711 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez-Francisco J. M., Santiago-García J. L., Loría-Bastarrachea M. I., Paul D. R., Freeman B. D., Aguilar-Vega M., CMS membranes from PBI/PI blends: Temperature effect on gas transport and separation performance. J. Membr. Sci. 597, 117703 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu L., Rungta M., Koros W. J., Matrimid® derived carbon molecular sieve hollow fiber membranes for ethylene/ethane separation. J. Membr. Sci. 380, 138–147 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosseini S. S., Chung T. S., Carbon membranes from blends of PBI and polyimides for N2/CH4 and CO2/CH4 separation and hydrogen purification. J. Membr. Sci. 328, 174–185 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Favvas E. P., Kouvelos E. P., Romanos G. E., Pilatos G. I., Mitropoulos A. C., Kanellopoulos N. K., Characterization of highly selective microporous carbon hollow fiber membranes prepared from a commercial co-polyimide precursor. J. Porous Mater. 15, 625–633 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatori H., Takagi H., Yamada Y., Gas separation properties of molecular sieving carbon membranes with nanopore channels. Carbon 42, 1169–1173 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hazazi K., Ma X., Wang Y., Ogieglo W., Alhazmi A., Han Y., Pinnau I., Ultra-selective carbon molecular sieve membranes for natural gas separations based on a carbon-rich intrinsically microporous polyimide precursor. J. Membr. Sci. 585, 1–9 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.X. Ma, J. Lin, in Modern Inorganic Synthetic Chemistry (Elsevier, 2017), pp. 669–686. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du N., Park H. B., Robertson G. P., Dal-Cin M. M., Visser T., Scoles L., Guiver M. D., Polymer nanosieve membranes for CO2-capture applications. Nat. Mater. 10, 372–375 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campo M. C., Magalhaes F. D., Mendes A., Carbon molecular sieve membranes from cellophane paper. J. Membr. Sci. 350, 180–188 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Vos R. M., Verweij H., High-selectivity, high-flux silica membranes for gas separation. Science 279, 1710–1711 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H., Song Z., Zhang X., Huang Y., Li S., Mao Y., Ploehn H. J., Bao Y., Yu M., Ultrathin, molecular-sieving graphene oxide membranes for selective hydrogen separation. Science 342, 95–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myglovets M., Poddubnaya O. I., Sevastyanova O., Lindström M. E., Gawdzik B., Sobiesiak M., Tsyba M. M., Sapsay V. I., Klymchuk D. O., Puziy A. M., Preparation of carbon adsorbents from lignosulfonate by phosphoric acid activation for the adsorption of metal ions. Carbon 80, 771–783 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu L., Liu J., Zhu L., Hou X., Huang L., Lin H., Cheng J., Highly permeable mixed matrix materials comprising ZIF-8 nanoparticles in rubbery amorphous poly(ethylene oxide) for CO2 capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 205, 58–65 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultrich B., Scheibe H. J., Grandremy G., Schneider D., Elastic modulus of amorphous carbon films. Phys. Status Solidi 145, 385–392 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borjigin H., Stevens K. A., Liu R., Moon J. D., Shaver A. T., Swinnea S., Freeman B. D., Riffle J. S., McGrath J. E., Synthesis and characterization of polybenzimidazoles derived from tetraaminodiphenylsulfone for high temperature gas separation membranes. Polymer 71, 135–142 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giel V., Kredatusová J., Trchová M., Brus J., Žitka J., Peter J., Polyaniline/polybenzimidazole blends: Characterisation of its physico-chemical properties and gas separation behaviour. Eur. Polym. J. 77, 98–113 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gadipelli S., Travis W., Zhou W., Guo Z., A thermally derived and optimized structure from ZIF-8 with giant enhancement in CO2 uptake. Energ. Environ. Sci. 7, 2232–2238 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sugama T., Hydrothermal degradation of polybenzimidazole coating. Mater. Lett. 58, 1307–1312 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu M., Funke H. H., Noble R. D., Falconer J. L., H2 separation using defect-free, inorganic composite membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1748–1750 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng Y., Li Y., Ban Y., Jin H., Jiao W., Liu X., Yang W., Metal-organic framework nanosheets as building blocks for molecular sieving membranes. Science 346, 1356–1359 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peng Y., Li Y., Ban Y., Yang W., Two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets for membrane-based gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 9757–9761 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim H. W., Yoon H. W., Yoon S.-M., Yoo B. M., Ahn B. K., Cho Y. H., Shin H. J., Yang H., Paik U., Kwon S., Choi J.-Y., Park H. B., Selective gas transport through few-layered graphene and graphene oxide membranes. Science 342, 91–95 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang A., Liu Q., Wang N., Zhu Y., Caro J., Bicontinuous zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-8@GO membrane with enhanced hydrogen selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14686–14689 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ying Y., Tong M., Ning S., Ravi S. K., Peh S. B., Tan S. C., Pennycook S. J., Zhao D., Ultrathin two-dimensional membranes assembled by ionic covalent organic nanosheets with reduced apertures for gas separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4472–4480 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen J., Liu G., Ji Y., Liu Q., Cheng L., Guan K., Zhang M., Liu G., Xiong J., Yang J., Jin W., 2D MXene nanofilms with tunable gas transport channels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1801511 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Achari A., Sahana S., Eswaramoorthy M., High performance MoS2 membranes: Effects of thermally driven phase transition on CO2 separation efficiency. Energ. Environ. Sci. 9, 1224–1228 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song H., Wei Y., Qi H., Tailoring pore structures to improve the permselectivity of organosilica membranes by tuning calcination parameters. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 24657–24666 (2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S8

Tables S1 to S10

References