Abstract

Evasion, approach and predation are examples of innate behaviour that are fundamental for the survival of animals. Uniting these behaviours is the assessment of threat, which is required to select between these options. Far from being comprehensive, we give a broad review over recent studies utilising optic techniques that have identified neural circuits and genetic identities underlying these behaviours.

Keywords: approach, evasion, genetic, neural, predation

INTRODUCTION

Risk cannot be destroyed, only transformed. As animals perceive danger, they can engage in flight to avoid potential harm; but this comes at the expense of foregoing exploration, foraging and pursuit, which bears the risk of not being able to locate resources, conspecifics and assessing the environment. Conversely, when potential threat is perceived to be sufficiently low, predation represents a state where animals pursue nutrition at the risk of exposing themselves to other predators and bodily harm. Failure to accurately gauge danger and select appropriate behavioural outputs can severely impact an animal’s ability to survive. Thus, neural circuits that are able to assess the scale of danger and ultimately engage appropriate behavioural output are fundamental for the survival of animals.

PHYSIOLOGY AND GENETIC MARKERS FOR EVASION NEURONS

During states of perceived danger, animals may engage in evasive behaviours for survival; commonly manifested as flight in rodents.

Ventral tegmental area (VTA) Gad2 neurons have been shown to mediate flight in response to a looming stimulus and their photoactivation is sufficient to invoke flight in the absence of a stimulus (Zhou et al., 2019). VTAGad2 neurons in turn have been shown to project to the central amygdala (CeA), lateral hypothalamus (LH), and periaqueductal grey (PAG), although whether activation of these projections is sufficient to induce flight has yet to be shown.

Potentially upstream of the VTA, optogenetic activation of paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH) Sim1 neuron projections to the ventral midbrain (vMB) also elicits flight (Mangieri et al., 2019) and the induction of Fos in non-dopaminergic vMB neuron, which raises the possibility that VTAGad2 neurons may be a target of PVHSim1 neurons. Although PVH neurons and more specifically PVHCRH are responsive to looming threats, their suppression in response to appetitive stimuli suggests that they may mediate negative valence as opposed to assessing danger per se (Kim et al., 2019).

More anterior to the PVH, MPAvGluT2–PAG projections have been shown to mediate certain evasive behaviours, such as jumping (Zhang et al., 2021). Results during an open-field test suggest that it may be driven by a state of severe anxiousness.

Ventromedial hypothalamic (VMH) SF1 neurons have also been implicated in evasive and freezing behaviours (Kunwar et al., 2015). VMHSF1-anterior hypothalamic nucleus and VMHSF1-dorsolateral PAG (dlPAG) projections have been shown to induce jumping and freezing respectively (Wang et al., 2015). Activation of VMHSF1 neurons was also capable of modulating autonomic responses such as heart rate, which scaled with the intensity of photostimulation (Viskaitis et al, 2017); hinting towards a population coding mechanism within the VMHSF1 neuron population. A separate study used fibre photometry to show that dorsomedial (dmVMH) SF1 neurons in particular are physiologically responsive to various threatening stimuli including rats and ultrasonic sweeps, although notably were not responsive to looming stimuli thus suggesting that their responses to threatening stimuli are context or modality-specific (Kennedy et al., 2020).

Another PAG projection in the hypothalamus is the LHvGluT2 to ventrolateral PAG (vlPAG) and lateral PAG (lPAG) projection, photoactivation of which leads to evasive behaviour against a moving food dish (Li et al., 2018). Within the PAG, vlPAGGad2 neurons have been shown to receive excitatory input from dl/lPAGvGluT2 and inhibitory inputs CeAGad1 neurons. Optogenetic activation of either vlPAGGad2 or dl/lPAGvGluT2 neurons induces flight (Tovote et al., 2016). This is mediated in part by inhibiting the freezing response evoked by local vlPAGvGluT2 neurons. These findings raises the possibility that LHvGluT2 neurons may excite vlPAGGad2 neurons directly, or indirectly through dl/lPAGvGluT2 neurons, although this has yet to be tested. Interestingly a separate study recapitulated the flight caused by activation of dl/lPAGvGluT2 neurons, but then further showed that inhibition of these neurons during presentation of a looming stimulus can instead cause freezing (Evans et al., 2018), thus highlighting again the antagonistic relationship between flight and freezing.

Finally, a pontine projection towards the lPAG capable of driving flight, is the dorsal lateral parabrachial nucleus (dLPBN) to lPAG projection. Its photoactivation is capable of evoking running and jumping in rodents in response to various noxious stimuli (Chiang et al., 2020). Although this raises the possibility that this projection merely signals pain, it was shown instead to mediate analgesia, thus representing a higher-order response to danger by engaging both evasive motor behaviour and descending inhibition to aid survival.

Overall, various circuits are involved in shaping evasive behaviours. Interestingly, these circuits have been shown to interact with neural populations that can induce freezing, suggesting a mechanism of evaluating the magnitude of threat presented in order to select flight over freezing.

PHYSIOLOGY AND GENETIC MARKERS FOR APPROACH NEURONS

As animals face lower levels of perceived threat, they may begin to engage in exploratory or approach behaviour, which are required for finding prey, investigating objects and assessing the environment. Although ethologically relevant for foraging, mate-seeking and familiarisation with the environment, there is a relative lack of data regarding the neural circuits that mediate such behaviour. However, some data exists regarding neural populations that mediate approach towards objects in particular.

Photoactivation of medial preoptic area (MPA) CaMKIIα neuron projections to the lPAG has been shown to elicit robust approach and pursuit behaviour towards objects, to an extent where activation of the circuit can be used to guide the movement of mice in a remote, closed-loop manner (Park et al., 2018). Notably, the activity MPACaMKIIα neurons also increases during interactions with objects, even at the expense of social interactions, thus representing a physiologically relevant role of these neurons in approaching behaviour towards non-social targets.

However, photoactivation of a GABAergic MPA projection, the MPAVgat–PAG projections results in increased movement in an open field test and preference to the stimulated side in a real time place preference (RTPP) test (Zhang et al., 2021). Although this could be interpreted as an anxiolytic function, the inability of this projection to create reinforcement during a conditioned place preference test suggests that the increased preference seen in an RTPP test may simply be due to an increase in exploratory behaviour (Ryoo et al., 2021). Photoactivation of this projection is also incapable of affecting object interaction, suggesting a possible separation between object-directed exploration and innate exploration (non-homeostatic driven exploration).

More recently, optogenetic stimulation of zona incerta (ZI) Gad2 neuron projections to the lPAG have been shown to enhance investigation towards novel conspecifics and objects, and was recapitulated by photostimulation of a more discrete subpopulation of GABAergic ZI neurons, namely ZITac1 neurons (Ahmadlou et al., 2021). Moreover, fibre photometry and inhibition experiments showed these neurons are active during deep investigation with objects and is necessary for such deep investigation. However, whether this novelty-seeking behaviour results in increased exploration in the absence of objects and whether it is ethologically relevant for behaviours such as foraging remain open questions.

PHYSIOLOGY AND GENETIC MARKERS FOR PREDATION NEURONS

Threat-aversion is low during predatory behaviour, as animals potentially expose themselves to being predated on. Thus many of the same nodes involved in evasive behaviours could be expected to also be involved in predation by scaling down threat aversion.

Indeed, the CeA is well known for mediating evasive and freezing behaviours and has been implicated in hunting though CeAVgat–vlPAGvGluT2 projections, which have been shown to mediate the pursuit and capture of prey. A parallel CeAVgat to parvocellular reticular formation (PCRt) Vgat neuron projection mediates the mandibular movements required for killing of prey (Han et al., 2017). Notably, optogenetic activation of this CeAVgat population had no change on food intake or conspecific aggression, thus indicating specificity towards hunting prey.

Although photoactivation of MPACaMKIIα-lPAG projections can drive hunting-like behaviour both towards prey and objects such as pursuit and biting, while not affecting conspecific interactions (Park et al., 2018), it does not conclude with consumption suggesting that the pursuit and capture shown may be an extension of investigatory behaviour rather than hunger-driven.

Optogenetic activation of LHVgat-lPAG projections drives hunting of prey while imparting negative valence, but also leads to aggressive behaviour towards conspecifics and inedible objects (Li et al., 2018), suggesting that this pathway may extend to general aggression. However, activation of LHGad2 neurons, a partially separate GABAergic population in the LH, does not result in consumption of prey after capture or increased aggression toward conspecifics and moreover were associated with positive valence in an RTPP test (Rossier et al., 2021). Activation of medial ZI (ZIm) Vgat neuron projections to the vlPAG increased hunting rate while imparting positive valence (Zhao et al., 2019), independently of the increase in food intake normally seen from broadly activating ZIVgat neurons. The ZI was shown to receive prey-related sensory information through the superior colliculus (SC), activation of which can also lead to predatory behaviour (Shang et al., 2019). Since activation of ZIVgat was also shown to be able to evoke voracious feeding (Zhang and van den Pol, 2017), it is plausible that the hunting behaviour evoked by the ZI could be hunger-driven. However, another study showed that ZImGad2 neurons are associated with broad investigatory behaviour rather than hunting per se (Ahmadlou et al., 2021), which raises the possibility that the hunting evoked from activation of ZIVgat neurons may be an extension of investigatory behaviour, although it has yet to be shown whether ZImGad2 and ZImVgat neurons form majorly overlapping populations. Thus, the existence of multiple hunting circuits and their differing valences suggests that the primary motivation for hunting across these circuits may be different; which may range from hunger-driven, investigatory, generalised aggression or scaling down of threat-aversiveness.

THREAT ASSESSMENT AND DECISION IN THE PAG

The convergence of many of the circuits mentioned above at the PAG suggests that the PAG may act to generally integrate and evaluate various types of danger (McNaughton and Corr, 2018).

For instance, the capability of the PAG to drive either freezing or flight, through vlPAGvGluT2 and dl/lPAGvGluT2 neurons respectively (Tovote et al., 2016) and the ability of the latter to inhibit the former population, suggests that the PAG can drive diverse types of behaviour in response to differing degrees of perceived risk. Mild threats may elicit freezing, whereas more serious threats may require flight. Low perceived danger may facilitate exploration or pursuit which then pinnacles during predation. Findings such as the direct inhibition of vlPAGvGluT2 by CeAVgat neurons (Han et al., 2017) can be incorporated in this framework by positing that they may act to dampen the freezing response to facilitate predation. Conversely activation of LHvGluT2-vl/lPAG projections may increase the perception of threat, which may underlie the evasive behaviour in response to an otherwise innocuous stimulus (Li et al., 2018). Evidence in support of a rate-coding mechanism of the PAG in the assessment of risk was shown through optogenetic activation of dlPAGCaMKIIα neurons, which evoke freezing at lower frequencies and flight at higher frequencies (Deng et al., 2016). However, population coding mechanisms may also play a part, since endoscopic calcium imaging of dlPAG neurons showed distinct neural populations that are responsive to either higher or lower threatening situations (Reis et al., 2021).

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

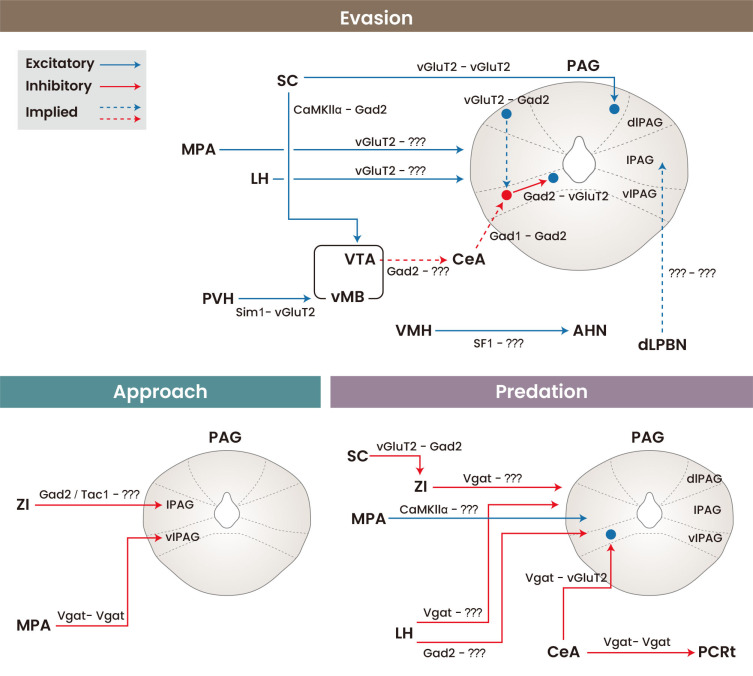

Although evasion, approach and predation represent outwardly very different behaviours, their tendency to all converge in the PAG suggests that they are all fundamentally behavioural outputs in response to a perceived level or absence of risk (Fig. 1). Most circuit-based studies of the PAG have identified particular behavioural outputs, but the exact type of information being conveyed by these upstream neural populations to drive the observed behaviour remains to be elucidated. In many studies, inputs from the SC have been implicated in conveying visual signals (Evans et al., 2018; Shang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019), which might be expected given the bias of tectal nuclei to mediate more lower-level sensory-motor reactions. This naturally raises the question as to how other sensory modalities are conveyed to the PAG and whether these connections are specific for innate behaviours. Aside from sensory signals, other relevant inputs include the motivational signals that may drive or inhibit evasion, approach or predation. Certain motivational drives may be able to modulate risk-aversion (e.g., hunger causing animals to forage or hunt despite the presence of a threat) and naturally raises the questions as to whether this occurs by lowering the perception of danger and/or by inhibiting evasive behaviours. How potentially competing motivational and sensory signals are processed in the PAG to calibrate risk and ultimately drive appropriate behavioural output remains an important question. Such research may require deeper understanding of the micro-circuitry within the PAG and its dynamics under different levels of threat. These types of experiments are challenging for regions such as the vlPAG, as fibre-based techniques may involve a certain degree of damage to the dlPAG above it, which may hamper its interactions with the vlPAG. Evidence for an ensemble-coding mechanism in the PAG also naturally raises the question as to whether these neural clusters are distinct in terms of their anatomical connections or neuropeptide identities. Finally, there is also sparse research using more modern neuroscience techniques regarding neural circuits that mediate innate exploration and novelty-seeking which are more risk-tolerant behaviours. This may in part be due to difficulties in distinguishing between curiosity-driven exploration and other types of goal-directed exploration, which may require the development of new behavioural models. Together, such future studies will help our understanding of how risk is assessed within the PAG.

Fig. 1. Schematic summary of neural circuits that evoke evasion, approach and predation.

Projection data based on terminal photostimulation experiments. Implied projections have supporting data but their behavioural outputs remain to be elucidated with terminal photostimulation experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Samsung Science and Technology Foundation under Project Number SSTF-BA1301-53, and KAIST Global Singularity Research Program. S.P. was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021R1I1A1A01060418).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.P. and J.R. wrote the manuscript. D.K. oversaw the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Ahmadlou M., Houba J.H., van Vierbergen J.F., Giannouli M., Gimenez G.A., van Weeghel C., Darbanfouladi M., Shirazi M.Y., Dziubek J., Kacem M., et al. A cell type-specific cortico-subcortical brain circuit for investigatory and novelty-seeking behavior. Science. 2021;372:eabe9681. doi: 10.1126/science.abe9681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang M.C., Nguyen E.K., Canto-Bustos M., Papale A.E., Oswald A.M.M., Ross S.E. Divergent neural pathways emanating from the lateral parabrachial nucleus mediate distinct components of the pain response. Neuron. 2020;106:927–939.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Xiao X., Wang Z. Periaqueductal gray neuronal activities underlie different aspects of defensive behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2016;36:7580–7588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4425-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.A., Stempel A.V., Vale R., Ruehle S., Lefler Y., Branco T. A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature. 2018;558:590–594. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Tellez L.A., Rangel M.J., Jr., Motta S.C., Jr., Zhang X., Jr., Perez I.O., Jr., Canteras N.S., Jr., Shammah-Lagnado S.J., Jr., van den Pol A.N., Jr., de Araujo I.E., Jr. Integrated control of predatory hunting by the central nucleus of the amygdala. Cell. 2017;168:311–324.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Kunwar P.S., Li L.Y., Stagkourakis S., Wagenaar D.A., Anderson D.J. Stimulus-specific hypothalamic encoding of a persistent defensive state. Nature. 2020;586:730–734. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Lee S., Fang Y.Y., Shin A., Park S., Hashikawa K., Bhat S., Kim D., Sohn J.W., Lin D., et al. Rapid, biphasic CRF neuronal responses encode positive and negative valence. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:576–585. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar P.S., Zelikowsky M., Remedios R., Cai H., Yilmaz M., Meister M., Anderson D.J. Ventromedial hypothalamic neurons control a defensive emotion state. Elife. 2015;4:e06633. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06633.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zeng J., Zhang J., Yue C., Zhong W., Liu Z., Feng Q., Luo M. Hypothalamic circuits for predation and evasion. Neuron. 2018;97:911–924.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangieri L.R., Jiang Z., Lu Y., Xu Y., Cassidy R.M., Justice N., Xu Y., Arenkiel B.R., Tong Q. Defensive behaviors driven by a hypothalamic-ventral midbrain circuit. Neuro. 2019;6:ENEURO.0156-19.2019. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0156-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N., Corr P.J. Survival circuits and risk assessment. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2018;24:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.G., Jeong Y.C., Kim D.G., Lee M.H., Shin A., Park G., Ryoo J., Hong J., Bae S., Kim C.H., et al. Medial preoptic circuit induces hunting-like actions to target objects and prey. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:364–372. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis F.M., Lee J.Y., Maesta-Pereira S., Schuette P.J., Chakerian M., Liu J., La-Vu M.Q., Tobias B.C., Ikebara J.M., Kihara A.H., et al. Dorsal periaqueductal gray ensembles represent approach and avoidance states. Elife. 2021;10:e64934. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64934.sa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier D., La Franca V., Salemi T., Natale S., Gross C.T. A neural circuit for competing approach and defense underlying prey capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021;118:e2013411118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013411118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo J., Park S., Kim D. An inhibitory medial preoptic circuit mediates innate exploration. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:716147. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.716147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang C., Liu A., Li D., Xie Z., Chen Z., Huang M., Li Y., Wang Y., Shen W.L., Cao P. A subcortical excitatory circuit for sensory-triggered predatory hunting in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:909–920. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovote P., Esposito M.S., Botta P., Chaudun F., Fadok J.P., Markovic M., Wolff S.B., Ramakrishnan C., Fenno L., Deisseroth K., et al. Midbrain circuits for defensive behaviour. Nature. 2016;534:206–212. doi: 10.1038/nature17996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viskaitis P., Irvine E.E., Smith M.A., Choudhury A.I., Alvarez-Curto E., Glegola J.A., Hardy D.G., Pedroni S.M., Pessoa M.R.P., Fernando A.B., et al. Modulation of SF1 neuron activity coordinately regulates both feeding behavior and associated emotional states. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3559–3572. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Chen I.Z., Lin D. Collateral pathways from the ventromedial hypothalamus mediate defensive behaviors. Neuron. 2015;85:1344–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.W., Shen L., Tao C., Jung A.H., Peng B., Li Z., Zhang L.I., Tao H.W. Medial preoptic area antagonistically mediates stress-induced anxiety and parental behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2021;24:516–528. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00784-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., van den Pol A.N. Rapid binge-like eating and body weight gain driven by zona incerta GABA neuron activation. Science. 2017;356:853–859. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.D., Chen Z., Xiang X., Hu M., Xie H., Jia X., Cai F., Cui Y., Chen Z., Qian L., et al. Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:921–932. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Liu X., Chen S., Zhang Z., Liu Y., Montardy Q., Tang Y., Wei P., Liu N., Li L., et al. A VTA GABAergic neural circuit mediates visually evoked innate defensive responses. Neuron. 2019;103:473–488.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]