Abstract

This article reports on the first meta-analysis of studies on the association between government-imposed social restrictions and mental health outcomes published during the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thirty-three studies (N = 131,844) were included. Social restrictions were significantly associated with increased mental health symptoms overall (d = .41 [CI 95% .17–.65]), including depression (d = .83 [CI 95% .30–1.37]), stress (d = .21 [CI 95% .01–.42]) and loneliness (d = .30 [CI 95% .07–.52]), but not anxiety (d= .26 [CI 95% −.04–.56]). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that the strictness and length of restrictions had divergent effects on mental health outcomes, but there are concerns regarding study quality. The findings provide critical insights for future research on the effects of COVID-19 social restrictions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Mental health, Loneliness, Meta-analysis

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the world, governments of many nations instituted a variety of social restrictions to “flatten the curve” and contain the exponential rise of case numbers and deaths from the virus. In many countries, social restrictions entailed strict lockdowns of regions, cities, and even entire countries, as well as quarantine measures for those who had (or were suspected to have) contracted the virus. However, humans have fundamental needs for social connection and emotional bonding [1,2]. The attainment of these needs is significantly compromised during times of social restriction when individuals are forced to isolate from family and other close members of their social network [3]. Indeed, numerous studies into social isolation highlight the many negative psychological outcomes associated with strict and enduring social isolation, which include, but are not limited to, depression, anxiety, loneliness, and post-traumatic stress [4, 5, 6].

Numerous commentaries, rapid reviews, and position papers published in the early stages of the pandemic raised concerns about the possible negative effects on mental health of the social isolation associated with these social restrictions [3,7]. This was followed by a large number of cross-sectional studies investigating the mental health effects of social restrictions and quarantine measures. Most of this work was motivated by the urgent need to generate evidence to determine whether pandemic-related social restrictions negatively impacted mental health.

One year on, government-mandated social restrictions continue to be enforced in many parts of the world due to problems with the timely roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines [8,9], vaccine hesitancy [9,10], and the high transmissibility of the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron variants [11,12]. To this end, the need for a solid evidence-base to guide mental health policies in times of social restrictions is timely and necessary.

Although there has been a rapid output of research, this fast response has come with potential costs. As noted recently [13], one such cost involves concerns about study quality. Moreover, research has generated contradictory findings regarding how social restrictions tend to be associated with certain mental health outcomes. The issue of study quality, coupled with the contradictory findings reported across studies, makes it difficult to interpret the effects of COVID-19 social restrictions on the overall mental health of people.

When we synthesize the published research investigating the effects of social restrictions on mental health outcomes during the first full year of the COVID-19 pandemic, what do we find? Is the strictness of social restrictions associated with an increase in mental health symptoms? Synthesizing the current evidence and determining its quality is essential to guard against the possible harmful effects of overly dramatic or inaccurate reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic, including mental health outcomes [13].

Methods

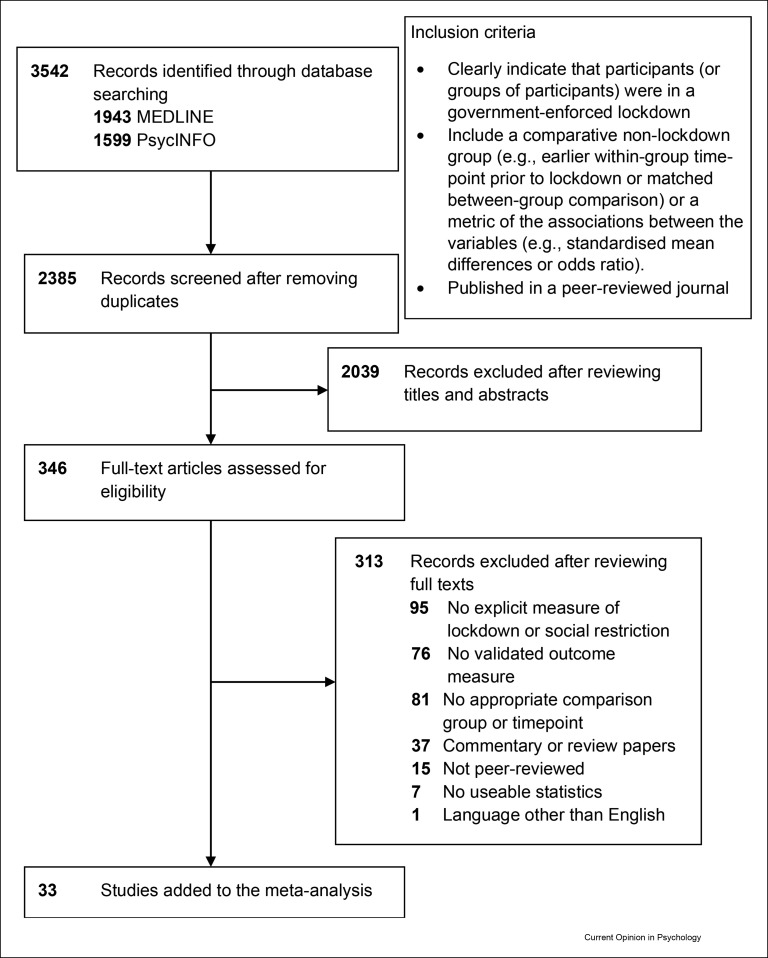

This meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA guidelines [14]. We conducted parallel systematic searches of MEDLINE and PsycINFO for all studies that investigated the relation between social isolation and mental health outcomes published in peer-reviewed journals between March 2020 and March 11, 2021 (to capture the first full year of the pandemic, World Health Organisation [WHO] [15]). Language was restricted to English. The reference lists of the included studies were manually searched. Key search terms reflected the main concepts: social restriction measures enforced by governments in response to COVID-19 and mental health outcomes. The full list of search terms appears in Table 1 and the criteria for study inclusion appear in Figure 1 . After duplicate articles were removed, two reviewers (LK & DR) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts of articles identified in the search using Covidence software. Disagreements regarding inclusion were discussed with the senior reviewer (GK) until consensus was reached. We did not contact authors to seek missing data.

Table 1.

Search terms.

| Key Concept | Social isolation during lockdown | Context | Mental health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free text terms |

|

|

|

| Controlled vocabulary terms/subject terms |

|

|

|

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flowchart.

Data analysis

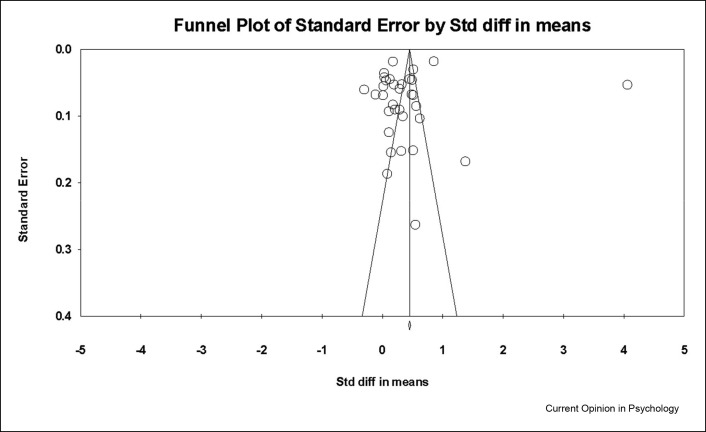

Statistical analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.3.070 CMA Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ [16]. The effect size metric varied across the studies. Thus, to allow for cross-study comparisons, all reported effect sizes were converted to a common metric – Cohen's d – in CMA. Five meta-analyses were conducted. The first estimated the effect size of social restriction on overall mental health symptoms. The other four meta-analyses estimated the effect size of social restriction (separately) on mental health outcomes for which there were multiple studies – namely – depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness. A random-effects model with restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used for each meta-analysis to account for heterogeneity between studies. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed with the Q statistic [17] and the I2 [18]. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger's regression intercept [19].

Subgroup moderator analyses were conducted when there were multiple studies present for each subgroup. These moderator analyses were based on the type of social restriction (low, moderate, or strict), length of exposure to social restrictions (less than 2 weeks, 2–4 weeks, more than one month), WHO region classification (Americas, Europe, or Western Pacific), age (under 18 years, 18–30 years, 31–59 years, 60+ years), and whether or not the sample had participants who reported pre-existing physical or mental health vulnerabilities. Additionally, we conducted a “study design” subgroup moderator analysis, which compared cross-sectional, retrospective reporting, and longitudinal studies. All subgroup moderator analyses were completed using random-effects models and z-tests to determine the significance of the difference in point estimates observed for each subgroup.

Study quality

The quality of each study was evaluated according to the National Institutes of Health's Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [20] (see supplemental material Table S1). To assess the impact of any poor quality, sensitivity analyses were conducted. To establish the stability of the overall effect estimates, a one-study-removed sensitivity analysis was undertaken in CMA to identify any outlier studies [16].

Results

In all, 3542 records were identified from both databases (see Figure 1), 1157 duplicate records were removed, and 2038 more studies were excluded because they were ineligible. This resulted in 346 full-text articles retrieved for further screening. Of these, 33 articles were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analyses (see Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Study characteristics of primary studies included in meta-analysis.

| Study | Country (WHO Region) | N | Age Mean (SD) |

Data collection period | Length of exposure to eocial restrictionsa (days) | Study design | Social restriction typeb | Comparison | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altieri & Santangelo (2021) [27] | Italy (Europe) | 84 | 63.6 (10.9) | April 21st – May 3rd 2020 | 49 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Retrospective pre-lockdown scores | Anxiety (HADS) Depression (HADS) |

| Brailovskaia & Margraf (2020) [28] | Germany (Europe) | 436 | 27.01 (6.41) | March 20th – March 28th 2020 | 4 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (October 2019) | Depression (DASS21) Anxiety (DASS21) Stress (DASS21) |

| Campos et al. (2020) [29] | Brazil (Americas) | 12,101 | Not reported | March 18th – June 25th 2020 | 7 | Cross-sectional | Low | Socialisation unchanged or better than usual (versus lower) | Depression (DASS21) Anxiety (DASS21) Stress (DASS21) Psychological Distress (IES-R) |

| Castellini et al. (2020) [30] | Italy (Europe) | 130 | 34.03 (14.03) | April 22nd – May 3rd 2020 | 42 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (December 2019–January 2020) | Depression (BSI) Anxiety (BSI) |

| Daly, Sutin & Robinson (2020) [31] | USA (Americas) | 5428 | 48.4 (16.3) | April 2020 | 0 | Cross-sectional | Moderate | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-2) |

| Davide et al. (2020) [32] | Italy (Europe) | 30 | 43.17 (14.87) | April 16th – April 17th 2020 | 42 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (January–February 2020) | OCD symptoms (Y-BOCS) |

| Elmer et al. (2020) [33] | Switzerland (Europe) | 212 | Not reported | April 2020 | 14 | Longitudinal | Low | Correlation between feeling socially isolated and outcomes | Depression (CES –DS) Stress (CES – SS) |

| Fiorillo et al. (2020) [34] | Italy (Europe) | 20,720 | 40.4 (14.3) | March–May 2020 | 21 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (DASS21) Anxiety (DASS21) Stress (DASS21) |

| Forte et al. (2020) [35] | Italy (Europe) | 2991 | 30.0 (11.5) | March 18th – March 31st 2020 | 10 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Retrospective pre-lockdown scores | Depression (SCL-90) Anxiety (SCL-90) Stress (SCL-90) |

| Giannopolou et al. (2020) [36] | Greece (Europe) | 442 | Not reported (Adolescents) | April 16th – April 30th 2020 |

21 | Cross-sectional | Low | Retrospective pre-lockdown scores | Depression (PHQ-9) Anxiety (GAD-7) |

| Groarke et al. (2020) [37] | United Kingdom (Europe) | 1964 | 37.11 (12.86) | March 23rd – April 24th 2020 | 0 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Loneliness (Three-Item Loneliness Scale) |

| Harris & Sandal (2020) [38] | Norway (Europe) | 4008 | Not reported | March 20th – March 27th 2020 | 7 | Cross-sectional | Unclear | Non-lockdown sample | Psychological Distress [depression & anxiety] (HSCL-10) |

| Hawes et al. (2021) [39] | New York, USA (Americas) | 283 | 17.49 (1.42) | March 27th – May 15th 2020 | 7 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (December 2014–July 2019) | Depression (CDI) Anxiety (SCARED) |

| Holloway et al. (2021) [40] | International | 8209 | Not reported | April 16th – May 4th 2020 | Unclear | Cross-sectional | Unclear | Non-lockdown sample | Anxiety (single item) Loneliness (single item) |

| Jia et al. (2020) [41] | United Kingdom (Europe) | 3097 | 44.0 (15.0) | April 3rd – April 30th | 11 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Prospective matched UK-normative sample (non-lockdown) | Depression (PHQ-9) Anxiety (GAD-7) Stress (PSS-4) |

| Krendl & Perry (2020) [42] | USA (Americas) | 87 | 75.20 (6.86) | April 21st – May 21st 2020 | 28 | Longitudinal | Moderate | Pre-lockdown scores (June–November 2019) | Depression (PHQ-9) Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale) |

| Li et al. (2020) [43] | China (Western Pacific) | 555 | 19.6 (3.4) | January 13th – January 15th 2020 | 15 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (December 2019) | Psychological Distress ([Depression & Anxiety] PHQ-4) |

| Lopez-Morales et al. (2020) [44] | Argentina (Americas) | 204 | 32.56 (4.71) | March 22nd – May 10th 2020 | T2: 14 T3: 47 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | Start of lockdown score (2–5 days into lockdown) | Depression (BDI-II) Anxiety (STAI) |

| Lu et al. (2020) [45] | China (Western Pacific) | 1849 | 30.62 (9.44) | March 6th – March 12th 2020 | 43 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (CED) |

| Magson et al. (2020) [46] | Australia (Western Pacific) | 248 | 14.4 (0.5) | May 5th – May 14th 2020 |

60 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (2019) | Depression (SCAS) Anxiety (SMFQ – CV) |

| Marroquin et al. (2020) [47] | USA (Americas) | 118 | 39.2 (11.5) | March 26th – March 28th 2020 | 7 | Longitudinal | Moderate | Pre-lockdown scores (2019) | Depression (CES –DS) Anxiety (GAD-7) |

| Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020) [48] | Spain (Europe) | 1112 | 33.80 (16.65) | April 2nd – April 12th 2020 |

20 | Longitudinal | Strict | Start of lockdown scores (−3 to 4 days into lockdown) | Depression (DASS21) |

| Ruggieri et al. (2020) [49] | Italy (Europe) | 113 | 32.05 (8.01) | March 25th – April 14th 2020 | 14 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (March 7th – 9th 2020; 2 days before lockdown) | Depression (DASS21) Anxiety (DASS21) Stress (DASS21) Loneliness (Three-Item Loneliness Scale) |

| Shi et al. (2020) [50] | China (Western Pacific) | 59,679 | 35.97 (8.22) | February 28th – March 11th 2020 | 36 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-9) Anxiety (GAD-7) Stress (ASDS) |

| Sibley et al. (2020) [51] | New Zealand (Western Pacific) | 1003 | 51.6 (13.2) | March 26th – April 12th 2020 | 1 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (October–December 2019) | Psychological distress (K-6) |

| Tang, F. et al. (2020) [52] | China (Western Pacific) | 1160 | Not reported | February 5th – February 7th 2020 | 13 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (CES –DS) Anxiety (GAD-7) |

| Tang, W. et al. (2020) [53] | China (Western Pacific) | 256 | 19.81 (1.55) | February 20th – February 27th 2020 | 28 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-9) PTSD (PCL-C) |

| Tull et al. (2020) [54] | USA (Americas) | 500 | 40.0 (11.6) | March 27th – April 5th 2020 | unclear | Cross-sectional | Moderate | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (DASS21) Health anxiety (SHAI) Loneliness (UCLA loneliness Scale) |

| White & Van der Boor (2020) [55] | United Kingdom (Europe) | 600 | 36.75 (13.44) | March 31st – April 3rd 2020 | 7 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Retrospective pre-lockdown scores | Depression (HADS) anxiety (HADS) |

| Wilson et al. (2020) [56] | USA (Americas) | 848 | 48.02 (16.30) | March 30th – April 5th 2020 | unclear | Longitudinal | Unclear | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-9) anxiety (GAD-7) |

| Wong et al. (2020) [57] | Hong Kong (Western Pacific) | 583 | 70.9 (6.1) | March 24th – April 15th 2020 | 0 | Longitudinal | Strict | Pre-lockdown scores (October–December 2019) | Depression (PHQ-9) Anxiety (GAD-7) Loneliness (De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale) |

| Xin et al. (2020) [58] | China (Western Pacific) | 515 | 19.9 (1.6) | February 1st – February 20th 2020 | 3 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-9) |

| Zhu et al. (2020) [59] | China (Western Pacific) | 2279 | Not reported | February 12th – March 17th 2020 | 14 | Cross-sectional | Strict | Non-lockdown sample | Depression (PHQ-9) Anxiety (GAD-7) |

Note. ASDS, Acute Stress Disorder Scale; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; CDI, Children's Depression Inventory; CES – DS, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; CES – SS, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Stress Scale; DASS21, Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale – 21; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder- 7; HADS, Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale; HSCL-10, Hopkins Symptom Checklist; IES-R, Impact of Events Scale – Revised; K-6, Kessler-6; PCL-C, PTSD Check List- Civilian Version; PHQ-9, The Patient Health Questionnaire- 9; PHQ-2, The Patient Health Questionnaire- 2; PSS-4, Perceived Stress Scale- 4; SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Disorders; SCAS, Spence Children's Anxiety Scale; SCL-90, Symptom Checklist- 90; SHAI, Short Health Anxiety Inventory; SMFQ – CV, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-child version; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

At the start of data collection time.

Type of Social Restriction: Strict = Stay at home order enforced, closure of non-essential businesses, all public venues closed, social gatherings banned, travel banned; Moderate = Stay at home order not enforced, closure of non-essential businesses, plus restrictions on public gatherings, domestic quarantine for close contacts of confirmed cases, restriction on travel; Low = Stay at home order not enforced, closure of non-essential businesses.

The intra-class correlation between reviewers was high (0.96, 95% CI 0.89–0.98) for study quality assessment, and studies were generally rated poor (n = 14) or fair (n = 16) in quality (see Table 3 ) on the four-point scale, which ranged from poor to excellent. The most common risk to study quality was not having a clearly defined or reliable measure of social restrictions; in many cases, global assumptions were made regarding participants’ experiences and compliance with social restrictions. Additionally, some studies did not allow a sufficient timeframe to witness an association between exposure to social isolation due to lockdown and mental health outcomes (i.e., studies that were cross-sectional, or collected data on the day social restrictions commenced). Finally, although confounding variables were measured in some studies (e.g., whether people were isolating alone, satisfaction with social restriction measures, having or knowing someone who had COVID-19), many studies did not measure confounding variables, such as pre-existing mental health conditions, previous history of experiencing loneliness, or enduring vulnerability and resiliency factors.

Table 3.

Study quality ratings.

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altieri & Santangelo (2021) [27] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | Poor |

| Brailovskaia & Margraf (2020) [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0.5 | Fair |

| Campos et al. (2020) [29] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Poor |

| Castellini et al. (2020) [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | Good |

| Daly, Sutin & Robinson (2020) [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 0.5 | Fair |

| Davide et al. (2020) [32] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Poor |

| Elmer et al. (2020) [33] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0.5 | Fair |

| Fiorillo et al. (2020) [34] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Poor |

| Forte et al. (2020) [35] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Poor |

| Giannopolou et al. (2020) [36] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Poor |

| Groarke et al. (2020) [37] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Poor |

| Harris & Sandal (2020) [38] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Poor |

| Hawes et al. (2021) [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 0.5 | Fair |

| Holloway et al. (2021) [40] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Poor |

| Jia et al. (2020) [41] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Fair |

| Krendl & Perry (2020) [42] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Fair |

| Li et al. (2020) [43] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0.5 | Fair |

| Lopez-Morales et al. (2020) [44] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Good |

| Lu et al. (2020) [45] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Fair |

| Magson et al. (2020) [46] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | Good |

| Marroquin et al. (2020) [47] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 0.5 | Good |

| Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020) [48] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Poor |

| Ruggieri et al. (2020) [49] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | Poor |

| Shi et al. (2020) [50] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Fair |

| Sibley et al. (2020) [51] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Fair |

| Tang, F. et al. (2020) [52] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Fair |

| Tang, W. et al. (2020) [53] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Fair |

| Tull et al. (2020) [54] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 | Fair |

| White & Van der Boor (2020) [55] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Poor |

| Wilson et al. (2020) [56] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Fair |

| Wong et al. (2020) [57] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA | 1 | 1 | Good |

| Xin et al. (2020) [58] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0.5 | Poor |

| Zhu et al. (2020) [59] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 0 | Poor |

The overall pooled point estimate of the effect of social restrictions on overall mental health symptoms (i.e., all outcomes combined) was .41 (see Table 4 ). When mental health symptoms were broken down by the four outcomes for which there were multiple studies (i.e., depression [k = 27], anxiety [k = 19], stress [k = 9] and loneliness [k = 6]), the pooled point estimates for each outcome varied between d = 0.21 and 0.83 (see Table 4; forest plots are presented in the supplementary material [Figures S1-S4]). Specifically, people who experienced social restrictions reported significantly higher levels of depression, stress, and loneliness. However, no significant association was found between social restrictions and anxiety. Substantial heterogeneity was detected in all meta-analyses of the pooled estimates.

Table 4.

Results of random-effects meta-analyses.

| Outcome | Number of Studies | Cohen's d (95% CIs) | Q statistic (df) [I2] | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mental health symptoms | 33 | .41 (.17–.65) | 6154.43 (32) [99.48] | <.0001 |

| Depression | 27 | .83 (.30–1.37) | 21668.73 (26) [99.88] | <.0001 |

| Anxiety | 19 | .26 (−.04–.56) | 4013.08 (18) [99.55] | = .098 |

| Stress | 9 | .21 (.01–.42) | 687.01 (8) [98.84] | = .044 |

| Loneliness | 6 | .30 (.07–.52) | 53.40 (5) [90.64] | = .009 |

Subgrouping of studies by different characteristics further revealed several significant effects on the point estimates (effect sizes and z-tests available in supplementary material [Tables S2-S3]). Depression was significantly higher in people exposed to strict compared to moderate social restrictions (Z = 2.07, p = 0.04), whereas anxiety was significantly higher for those exposed to low compared to moderate social restrictions (Z = 3.88, p = 0.0001). In terms of length of exposure to social restrictions (less than 2 weeks, 2–4 weeks, or 1+ month), stress was significantly higher for people experiencing shorter social restrictions (i.e., less than 2 weeks) compared to those experiencing longer restrictions (i.e., 2–4 weeks [Z = 2.11, p = .03] and 1+ month [Z = 2.09, p = .04]). Participants from the European region reported significantly more depression than did those from other regions (i.e., Americas [Z = 2.16, p = .03] and Western Pacific [Z = 2.16, p = .03]). Additionally, outcomes of depression were significantly higher among people who reported no pre-existing physical or mental health conditions than those who did (Z = 2.02, p = .04), and among people under age 18 (Z = 4.60, p = .01) or between 31 and 59 (Z = 2.20, p = .03) compared with older adults (aged 60+ years). All other subgroup moderator analyses either showed no significant effect on the overall point estimates, or there were too few studies to conduct the moderator analysis (see supplementary material [Tables S2-S3]). The “study design” subgroup moderator analyses indicated that the magnitude of the effect size for all outcomes did not differ significantly as a function of study design (i.e., cross-sectional, retrospective reporting, or longitudinal designs; see supplementary material [Tables S2-S3]).

Visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated no potential publication bias (see Figure 2 ). Confirming this, Egger's regression intercept was not significant (intercept = −1.40; SE = 4.34; p = 0.75). Although there is no evidence of publication bias, the overall point estimates should be interpreted with caution due to the high heterogeneity of the data.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of all studies.

Although the study quality subgroup moderator analyses revealed no significant impact of poor study quality on the point estimates (see supplementary material [Table S2]), visual inspection of the forest plots identified one study [34] as a potential outlier. However, removing this study from the meta-analyses did not significantly change the overall pooled estimates or 95% confidence intervals for any of the outcomes (see supplementary material [Table S2]). In fact, the point estimate remained significant and 95% CIs overlapped in all iterations of the one-study-removed analysis (see supplementary material [Figures S5-S8]).), indicating that no study had an undue influence on the point estimates.

Discussion

Our quantitative synthesis of 33 studies demonstrates that, overall, mental health symptoms were significantly worse when people were exposed to mandated social restrictions and quarantine measures. Our subgroup analyses suggest that the strictness and length of social restrictions have divergent effects on depression, anxiety and stress (but not loneliness). For depression, strict restrictions are associated with higher symptoms; for anxiety, low social restrictions are associated with higher symptoms; for stress, shorter social restrictions are associated with greater stress symptomatology. Furthermore, subgroup analyses that examined the moderating effects of age and having a pre-existing physical or mental health condition revealed significant differences between subgroups, but only for depression.

One limitation common to many of the published studies included in this meta-analysis is the failure to assess important individual difference variables, personal vulnerabilities, and contextual factors that could clarify our understanding of the associations between social restrictions and mental health outcomes [3,21]. As part of our meta-analysis, subgroup analyses of such factors was limited to only two variables – both individual difference factors – age and having an existing physical or mental health condition. Nevertheless, there is a need for integrative research that takes into account the inherent complexities and confluence of a variety of factors that can affect mental health symptoms. These include, but are not limited to, the multiple contextual stressors brought on by the pandemic such as financial/job insecurity, health anxieties and concerns regarding virus contagion, socio-economic and cultural differences, media reporting of the pandemic, and the role of individual difference variables, including enduring vulnerabilities (e.g., negative affectivity, difficulties regulating emotions), resiliency factors (e.g., problem-focused coping styles, trait optimism), and interpersonal factors (e.g., the quality of familial relationships and the strength of social networks). Moreover, such integrative approaches should consider how facets of mental health and wellbeing are inter-related. In the context of COVID-19 social restrictions, it is important to consider how loneliness may act as an explanatory variable in understanding the association between social restrictions and mental health outcomes such as depression and anxiety. Various reviews of the effects of loneliness find moderate associations between loneliness and such facets of mental health [22]. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 crisis, loneliness has been especially prevalent among helpline callers, particularly during periods of strict social restrictions [23]. Thus, research that adopts a multifactorial, integrative perspective to the study of COVID-19 social restriction measures is likely to be best positioned to provide informative explanations regarding the effects of these restrictions on individuals’ mental health [3,21].

Although there were no significant differences in the findings as a function of study quality, 91% of the studies had poor-to-fair quality. This highlights another limitation of existing research and raises concerns regarding the confidence that can be placed in the broader findings on relations between COVID-19 social restrictions and mental health effects [13]. The biggest study quality issue involved the validity of assessments of participants' exposure to social restrictions. Most studies made global assumptions about people's experiences and compliance with social restrictions. Even longitudinal studies, many of which compared pre-social-restriction assessments of mental health with assessments conducted during social restriction, did not model time as a continuous variabl. However, modelling time as continuous would have allowed participants' mental health symptoms at the time of data collection to be mapped onto the number of days each participant had experienced a certain amount of social restriction. Moreover, given the wide-ranging period during which data collection occurred in particular studies, even some of the longitudinal studies do not provide a clear picture of the effects of lockdown on mental health. Thus, future research must model time as a continuous variable, implement better assessments of the duration and adherence to social restrictions, and use these findings to inform public health policies.

Future studies should also collect multiple assessments of mental health symptoms during and after social restrictions, to model mental health trajectories. Doing so may clarify when mental health symptoms are at their highest and help determine recovery time. For example, our findings suggest that stress may be highest during the earlier stages of social restrictions, as people struggle to adjust to the changes. The modelling of linear and non-linear patterns of change may provide critical insights into the timing of public health interventions to address mental health issues within different populations. The leveraging of digital technologies for the monitoring of symptoms, coupled with the delivery of self-directed e-therapies and the provision of telehealth, can offer cost-effective solutions with wide reach and penetrability for addressing population-level mental health issues when social restrictions preclude access to in-person mental health support and services. The coupling of frequent assessments of mental health symptoms along with self-directed digital interventions can provide an opportunity to track the mental health of individuals and trigger push notifications to engage in tailored programs or activities when subclinical or clinical levels of mental health symptoms are logged.

Given that social restrictions were found to be associated with increases in loneliness, and that those who experience a lack of social contact often report feeling lonely [24], it may be important to promote digital technologies and interventions that provide opportunities for lonely individuals to have social contact with others in virtual environments. For instance, in addition to encouraging people to connect with family and friends online, access to interventions that help people meaningfully (re)develop group memberships and social identities may be especially important (see Haslam et al. [60], this issue). At the very least, providing moderated forums that help those experiencing loneliness during social restrictions to connect with others may be useful, given that contact, even amongst strangers, is important for enhancing wellbeing [25,26].

In closing, the current research represents the first quantitative synthesis of the effects of COVID-19 social restrictions on mental health outcomes during the first full year of the pandemic. The findings clarify the state of the field regarding whether social restrictions are, in fact, associated with the psychological wellbeing of individuals. These findings offer novel insights that can: (a) guide and hopefully enhance the quality of future mental health research, and (b) inform policy to support the psychological wellbeing of citizens experiencing the strain of social restrictions.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

This review comes from a themed issue on Separation, Social Isolation, and Loss (2022)

Edited by Gery C. Karantzas and Jeffry A. Simpson

Footnotes

Given his role as Guest Editor, Gery Karantzas and Jeffry Simpson had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer-review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Paul Van Lange.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101315.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bowlby J. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis; London: 1969. Attachment and loss: volume 1: attachment. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52:664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This rapid review draws on studies that investigated past pandemics to provide initial insights into the effects of social restrictions on mental health that could be applied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 4.Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawryluck L., Gold W.L., Robinson S., Pogorski S., Galea S., Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1206. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohde N., D'Ambrosio C., Tang K.K., Rao P. Estimating the mental health effects of social isolation. Appl Res Qual Life. 2015;11:853–869. doi: 10.1007/s11482-015-9401-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L.…Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An authoritative position paper that takes an integrative approach to outlining the public health response to deal with mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 8.Tregoning J.S., Flight K.E., Higham S.L., Wang Z., Pierce B.F. Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00592-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wouters O.J., Shadlen K.C., Salcher-Konrad M., Pollard A.J., Larson H.J., Teerawattananon Y., Jit M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arce J.S.S., Warren S.S., Meriggi N.F., Scacco A., McMurry N., Voors M., Mobarak A.M. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low-and middle-income countries. Nat Med. 2020;27:1385–1394. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.11.21253419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen H., Vusirikala A., Flannagan J., Twohig K.A., Zaidi A., Chudasama D., Kall M. Public Health England; 2021. Increased household transmission of COVID-19 cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern B. 1.617. 2: a national case-control study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupferschmidt K., Wadman M. Delta variant triggers new phase in the pandemic. Science. 2021;372:1375–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.372.6549.1375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet Psychiatry Editorial COVID-19 and mental health. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;8:87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An authoritative editorial that outlines some of the major trends emerging from research into the effects of COVID-19 on mental health.

- 14.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . 2020. March 11): WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID19.https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]; WHO statement announcing COVID-19 as a pandemic and outlining the nature of the virus and its possible impact on the world.

- 16.Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P.T., Rothstei H.R. John Wiley & Sons; United Kingdom: 2009. Introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochran W.G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. doi: 10.2307/3001666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2020;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021, July. Study quality assessment tools.https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J.J., Baicker K., Boggio P.S., Capraro V., Cichocka A., Cikara M., Crockett M.J., Crum A.J., Douglas K.M., Druckman J.N., Drury J. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4:460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-0884-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An authoritative subdisciplinary perspective on how social and behavioral science can inform responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 22.Park C., Majeed A., Gill H., Tamura J., Ho R.C., Mansur R.B., Nasri F., Lee Y., Rosenblat J.D., Wong E., McIntyre R.S. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Res. 2020;294:113514. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brülhart M., Klotzbücher V., Lalive R., Reich S.K. Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature. 2021;600:121–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rumas R., Shamblaw A.L., Jagtap S., Best M.W. Predictors and consequences of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Res. 2021;300:113934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epley N., Schroeder J. Mistakenly seeking solitude. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143:1980–1999. doi: 10.1037/a0037323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Lange P.A.M., Columbus S. Vitamin S: why is social contact, even with strangers, so important to well-being? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2021;30:267–273. doi: 10.1177/09637214211002538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altieri M., Santangelo G. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2021;29:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. Predicting adaptive and maladaptive responses to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a prospective longitudinal study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2020;20:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos J.A., Martins B.G., Campos L.A., Marôco J., Saadiq R.A., Ruano R. Early psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a national survey. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2976. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellini G., Rossi E., Cassioli E., Sanfilippo G., Innocenti M., Gironi V.…Ricca V. A longitudinal observation of general psychopathology before the COVID-19 outbreak and during lockdown in Italy. J Psychosom Res. 2020;141:110328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J Affect Disord. 2020;278:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davide P., Andrea P., Martina O., Andrea E., Davide D., Mario A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with OCD: effects of contamination symptoms and remission state before the quarantine in a preliminary naturalistic study. Psychiatr Res. 2020;291:113213. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmer T., Mepham K., Stadtfeld C. Students under lockdown: comparisons of students' social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiorillo A., Sampogna G., Giallonardo V., Del Vecchio V., Luciano M., Albert U.…Volpe U. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur Psychiatr. 2020;63:1–11. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forte G., Favieri F., Tambelli R., Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world: effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the Italian population. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1802. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giannopoulou I., Efstathiou V., Triantafyllou G., Korkoliakou P., Douzenis A. Adding stress to the stressed: senior high school students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 nationwide lockdown in Greece. Psychiatr Res. 2020;295:113560. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groarke J.M., Berry E., Graham-Wisener L., McKenna-Plumley P.E., McGlinchey E., Armour C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris S.M., Sandal G.M. COVID-19 and psychological distress in Norway: the role of trust in the healthcare system. Scand J Publ Health. 2020;49:96–103. doi: 10.1177/1403494820971512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawes M.T., Szenczy A.K., Klein D.N., Hajcak G., Nelson B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holloway I.W., Garner A., Tan D., Ochoa A.M., Santos G.M., Howell S. Associations between physical distancing and mental health, sexual health and technology use among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Homosex. 2021;68:692–708. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia R., Ayling K., Chalder T., Massey A., Broadbent E., Coupland C., Vedhara K. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krendl A.C., Perry B.L. The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults' social and mental well-being. J Gerontol B. 2020;76B:53–58. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H.Y., Cao H., Leung D.Y., Mak Y.W. The psychological impacts of a COVID-19 outbreak on college students in China: a longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:3933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López-Morales H., Del Valle M.V., Canet-Juric L., Andrés M.L., Galli J.I., Poó F., Urquijo S. Mental health of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Psychiatr Res. 2020;295:113567. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H., Nie P., Qian L. Do quarantine experiences and attitudes towards COVID-19 affect the distribution of mental health in China? A quantile regression analysis. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11482-020-09851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y., Rapee R.M., Richardson C.E., Oar E.L., Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marroquín B., Vine V., Morgan R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatr Res. 2020;293:113419. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Idoiaga Mondragon N., Dosil Santamaría M., Picaza Gorrotxategi M. Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: an investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1491. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruggieri S., Ingoglia S., Bonfanti R.C., Coco G.L. The role of online social comparison as a protective factor for psychological wellbeing: a longitudinal study during the COVID-19 quarantine. Pers Indiv Differ. 2020:171. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi L., Lu Z.A., Que J.Y., Huang X.L., Liu L., Ran M.S., Gong Y.M., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y.K., Shi J. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sibley C.G., Greaves L.M., Satherley N., Wilson M.S., Overall N.C., Lee C.H.…Barlow F.K. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2020;75:618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang F., Liang J., Zhang H., Kelifa M.M., He Q., Wang P. COVID-19 related depression and anxiety among quarantined respondents. Psychol Health. 2020;36:164–178. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2020.1782410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang W., Hu T., Hu B., Jin C., Wang G., Xie C.…Xu J. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tull M.T., Edmonds K.A., Scamaldo K.M., Richmond J.R., Rose J.P., Gratz K.L. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychol Res. 2020;289:113098. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White R.G., Van Der Boor C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. BJPsych Open. 2020;6 doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson J.M., Lee J., Shook N.J. COVID-19 worries and mental health: the moderating effect of age. Aging Ment Health. 2020;29:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1856778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong S.Y., Zhang D., Sit R.W.S., Yip B.H.K., Chung R.Y.N., Wong C.K.M.…Mercer S.W. Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: a prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:e817–e824. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713021. https://bjgp.org/content/bjgp/70/700/e817.full.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xin M., Luo S., She R., Yu Y., Li L., Wang S.…Lau J.T.F. Negative cognitive and psychological correlates of mandatory quarantine during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am Psychol. 2020;75:607–617. doi: 10.1037/amp0000692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu S., Wu Y., Zhu C.Y., Hong W.C., Yu Z.X., Chen Z.K.…Wang Y.G. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haslam S.A., Haslam C., Cruwys T., Jetten J., Bentley S.V., Fong P., Steffens N.K. Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: implications for loneliness and mental health. COIP. 2022;43:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.