Abstract

Resistance to fluoroquinolone (FQ) antibiotics in Streptococcus pneumoniae has been attributed primarily to specific mutations in the genes for DNA gyrase (gyrA and gyrB) and topoisomerase IV (parC and parE). Resistance to some FQs can result from a single mutation in one or more of the genes encoding these essential enzymes. A group of 160 clinical isolates of pneumococci was examined in this study, including 36 ofloxacin-resistant isolates (MICs, ≥8 μg/ml) recovered from patients in North America, France, and Belgium. The susceptibilities of all isolates to clinafloxacin, grepafloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin were examined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards reference broth microdilution and disk diffusion susceptibility testing methods. Among the ofloxacin-resistant strains, 32 of 36 were also categorized as resistant to levofloxacin, 35 were resistant to sparfloxacin, 29 were resistant to grepafloxacin, and 19 were resistant to trovafloxacin. In vitro susceptibility to clinafloxacin appeared to be least affected by resistance to the other FQs. Eight isolates with high- and low-level resistance to the newer FQs were selected for DNA sequence analysis of the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE. The DNA and the inferred amino acid sequences of the resistant strains were compared with the analogous sequences of reference strain S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and FQ-susceptible laboratory strain R6. Reduced susceptibilities to grepafloxacin and sparfloxacin (MICs, 1 to 2 μg/ml) and trovafloxacin (MICs, 0.5 to 1 μg/ml) were associated with either a mutation in parC that led to a single amino acid substitution (Ser-79 to Phe or Tyr) or double mutations that involved the genes for both GyrA (Ser-81 to Phe) and ParE (Asp-435 to Asn). High-level resistance to all of the compounds except clinafloxacin was associated with two or more amino acid substitutions involving both GyrA (Ser-81 to Phe) and ParC (Ser-79 to Phe or Ser-80 to Pro and Asp-83 to Tyr). No mutations were observed in the gyrB sequences of resistant strains. These data indicate that mutations in pneumococcal gyrA, parC, and parE genes all contribute to decreased susceptibility to the newer FQs, and genetic analysis of the QRDR of a single gene, either gyrA or parC, is not predictive of pneumococcal resistance to these agents.

Increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents among contemporary clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been widely documented (3, 7, 8, 10, 27, 29). Resistance to penicillin, macrolides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and extended-spectrum cephalosporins has complicated the therapy of both invasive and respiratory infections due to pneumococci (6, 9, 17, 18). However, resistance to fluoroquinolones with notable activity against gram-positive bacteria, such as levofloxacin and ofloxacin, has been rare (2, 11, 14, 29). Therefore, fluoroquinolones may represent an attractive choice for empiric therapy of common respiratory infections, such as community-acquired pneumonia. Although rare, clinical isolates of pneumococci with mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of the DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV genes have been recognized (5, 11, 23, 24, 28) and have resulted in some therapeutic failures (5, 19, 23, 28).

This study examined the activities of ofloxacin, four recently marketed fluoroquinolones, and one investigational fluoroquinolone by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) broth microdilution and disk diffusion susceptibility testing procedures (20, 21) against a group of clinical pneumococcal isolates from North America and Europe that included 36 ofloxacin-resistant strains. To understand better the effect of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutations on the activities of the newer members of this class of antimicrobial agents, selected strains with high- and low-level fluoroquinolone resistance were characterized by genetic analysis. Mutations in the QRDRs of these genes were correlated with the susceptibility profiles of eight fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participating laboratories.

This collaborative study was conducted in microbiology laboratories at three separate institutions: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSC). The testing protocol, the quality control strains, the two microdilution antibiotic panels, and the lots of antibiotic disks were the same for the three laboratories, but the Mueller-Hinton sheep blood agar plates were from different sources (see below).

Antimicrobial agents.

Reagent powder of each antimicrobial agent was kindly provided for this study by the manufacturers. The agents (and their manufacturers) included clinafloxacin (Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, Mich.), grepafloxacin (Glaxo-Wellcome, Research Triangle Park, N.C.), levofloxacin and ofloxacin (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, N.J.), sparfloxacin (Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, Collegeville, Pa.), and trovafloxacin (Pfizer, New York, N.Y.). A single lot of standard disks of each agent (manufactured by Becton-Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) was provided to the three laboratories for the study.

Test isolates.

Each laboratory selected and tested 50 to 55 unique clinical pneumococcal isolates from its own culture collection. Included among these were 15 isolates recovered during recent resistance surveillance studies in France (see Acknowledgments) tested at MGH, 14 ofloxacin-resistant isolates from a North American surveillance study conducted from 1994 to 1996 (14) and tested at UTHSC, and 7 isolates from a recent surveillance study in Belgium tested at CDC. R6 is a well-characterized, fluoroquinolone-susceptible laboratory strain (13).

Quality control organisms.

Each laboratory included S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (20) and two ofloxacin-resistant strains, S. pneumoniae MN0418 and S. pneumoniae T62968, as quality control isolates in the antimicrobial susceptibility tests.

Broth microdilution susceptibility tests.

The MICs of each agent were determined by using the broth microdilution procedure described by NCCLS (20). This included use of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood as the test medium. Microdilution panels were prepared at one site (UTHSC) and were provided to each laboratory for the study. Panels were prepared to include each antimicrobial agent diluted in Mueller-Hinton medium from two commercial sources, Becton-Dickinson and Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). Test inocula were prepared from pneumococcal colonies grown on sheep blood agar plates that had been incubated at 35°C for 20 to 24 h in 5% CO2. The colonies were suspended in 0.9% saline to obtain a suspension with a turbidity equivalent to the turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard and were further diluted within 15 min to provide a final inoculum density of 5 × 105 CFU/ml in the wells of the microdilution panels. Colony counts for positive control wells were determined to ensure that the desired inoculum concentrations were being used. Microdilution panels were incubated at 35°C in ambient air for 20 to 24 h prior to visual determination of MICs.

Disk diffusion tests.

Disk diffusion tests were also performed according to the methods recommended by NCCLS (21) with 150-mm plates of Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood. Each laboratory used Mueller-Hinton agar from a different manufacturer, including commercially prepared plates from Becton-Dickinson and Remel (Lenexa, Kans.) and plates prepared in one of the laboratories (CDC) with Difco Mueller-Hinton agar. Plates were inoculated with an organism suspension that had a turbidity equivalent to that of a 0.5 McFarland standard and that was prepared in 0.9% saline as described above. The plates were incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 20 to 24 h prior to measurement of zone diameters.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA.

Genetic analysis of eight selected fluoroquinolone-resistant strains and fluoroquinolone-susceptible control strains was conducted at CDC. S. pneumoniae cells were grown to the late exponential phase in 10 ml of Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco) and were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–10 mM EDTA containing 0.5% deoxycholate and 0.1 mg of RNase per ml, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Proteinase K and Buffer AL (QIAamp Tissue Kit; QIAGEN, Chatsworth, Calif.) were added, and the mixture was incubated at 70°C for 30 min. The lysates were applied to QIAamp spin columns, and the genomic DNA was eluted according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

PCR and DNA sequencing.

Oligonucleotide primers PNC6 and PNC7 or PNC10 and PNC11 were used to amplify a 232-bp or a 329-bp gene fragment (excluding primers) of gyrA and parC, respectively (13), from the chromosomal DNA of each of the eight clinical isolates, isolate R6, and reference strain ATCC 49619. A 321-bp gene fragment of parE (excluding primers) was amplified with oligonucleotide primers SPPARE7 and SPPARE8 as described by Perichon et al. (26). Primers H4025 and H4026, described by Pan et al. (23), were used to amplify a 422-bp gene fragment of gyrB.

Amplification products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN). DNA sequencing was performed by ABI Prism dRhodomine terminator cycle sequencing (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with the ABI 377 automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems). DNA sequences were determined for both strands by using the products of independent PCRs. The GCG (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) genetic analysis programs were used for alignment of DNA sequences and deduced amino acid sequences.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequence data obtained in this study for gene fragments from S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 were assigned the following GenBank accession nos.: gyrA, AF065152; parC, AF065151; and parE, AF065153. The partial DNA sequence of parE from S. pneumoniae R6 was assigned GenBank accession no. AF058920.

RESULTS

The MICs of the six fluoroquinolones examined in this study did not differ significantly on the basis of the source of Mueller-Hinton basal medium used for testing (data not shown). Because MIC endpoints were somewhat better defined with the Difco medium, only those values will be detailed in the following paragraphs.

The investigational agent clinafloxacin was the most active fluoroquinolone examined in this in vitro study against both the ofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant strains (Tables 1 and 2). The next most active agent was trovafloxacin, followed by grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, and levofloxacin. The MICs of the agents for the high-level ofloxacin-resistant strains increased from 16- to 64-fold, whereas the clinafloxacin MICs for the resistant isolates appeared to increase less. Table 2 indicates the MICs recorded for the study isolates and the percentage of strains resistant to each agent.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of 160 selected S. pneumoniae clinical isolates to six quinolones

| Quinolone | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ofloxacin-susceptible isolates (n = 124)

|

Ofloxacin-resistant isolates (n = 36)b

|

|||||

| 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | Range | |

| Ofloxacin | 2 | 2 | 0.5–4 | >16 | >16 | 8–>16 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 1 | 0.5–2 | 16 | 16 | 4–16 |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.12–0.5 | 8 | 16 | 1–16 |

| Grepafloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.12–0.5 | 8 | 16 | 1–>16 |

| Trovafloxacin | ≤0.12 | 0.25 | ≤0.12–0.5 | 4 | 8 | 0.5–16 |

| Clinafloxacin | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12–0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25–1 |

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates, respectively, are inhibited.

Ofloxacin resistance is defined by an MIC of ≥8 μg/ml.

TABLE 2.

Comparative activities of quinolones against ofloxacin-susceptible and ofloxacin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates

| Strain and quinolone | No. of strains for which MICs (μg/ml) were as follows:

|

% Resistancea | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | >16 | ||

| Ofloxacin-susceptible strains (n = 124) | ||||||||||

| Ofloxacin | 1 | 10 | 107 | 6 | 0 | |||||

| Levofloxacin | 12 | 107 | 5 | 0 | ||||||

| Sparfloxacin | 9 | 81 | 34 | 0 | ||||||

| Grepafloxacin | 44 | 69 | 11 | 0 | ||||||

| Trovafloxacin | 97 | 26 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Clinafloxacin | 123 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Ofloxacin-resistant strains (n = 36) | ||||||||||

| Ofloxacin | 5 | 13 | 19 | 100 | ||||||

| Levofloxacin | 5 | 13 | 18 | 86 | ||||||

| Sparfloxacin | 1 | 9 | 1 | 15 | 10 | 97 | ||||

| Grepafloxacin | 7 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 81 | |||

| Trovafloxacin | 7 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 53 | |||

| Clinafloxacin | 6 | 28 | 2 | |||||||

Based on approved NCCLS resistance breakpoints.

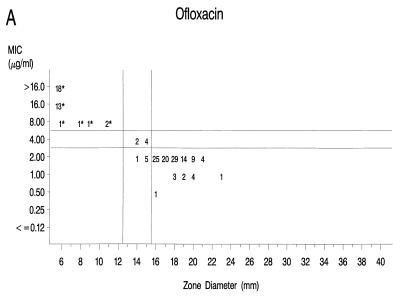

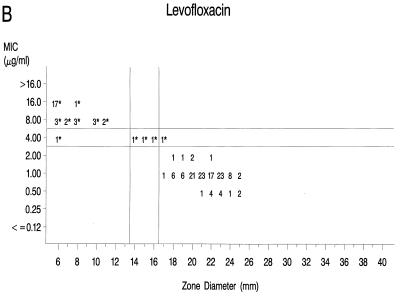

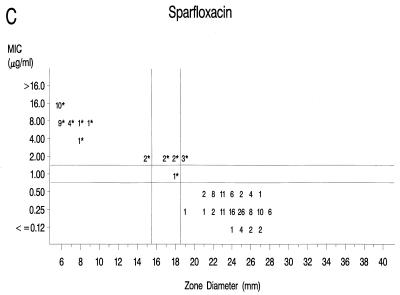

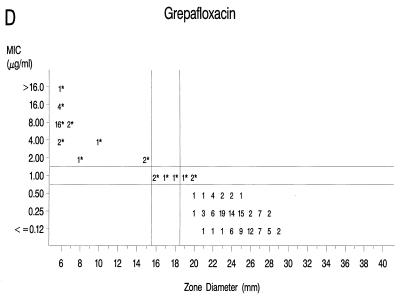

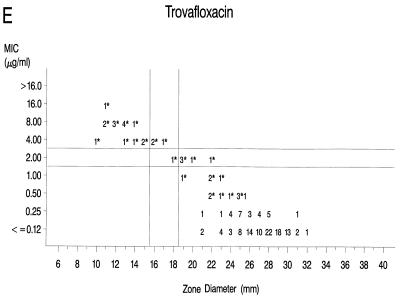

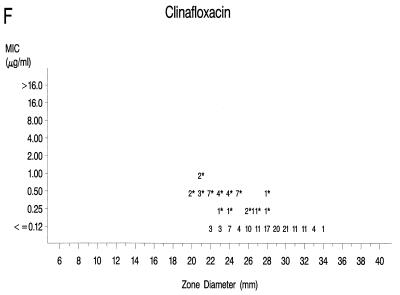

Graphs that relate MICs to disk diffusion zone diameters are presented in Fig. 1A to F. Approved NCCLS MIC and zone diameter breakpoints for each agent with the exception of clinafloxacin are indicated on each graph; the MIC and zone diameter breakpoints for clinafloxacin have not yet been established. The source of Mueller-Hinton agar used to prepare the agar disk diffusion plates did not appear to affect the fluoroquinolone zone diameters appreciably (data not shown). With grepafloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin, the MICs were increased and the zone diameters were reduced for the ofloxacin-resistant strains. A comparison of the error rates generated with the NCCLS MIC and disk diffusion tests is shown in Table 3. Application of the approved NCCLS breakpoints resulted in only a few minor errors for all drugs but three very major errors with sparfloxacin. Test strains segregated into three groups according to the MICs: (i) those highly susceptible to all agents, (ii) those highly resistant to grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin (i.e., MICs ≥ 4 μg/ml), and (iii) isolates for which MICs were moderately elevated (MICs of 1 to 2 μg/ml for sparfloxacin and grepafloxacin and 0.5 to 1 μg/ml for trovafloxacin). Eight isolates from the latter two categories were selected for genetic characterization (Table 4).

FIG. 1.

Scatterplots of quinolone MICs and disk diffusion zone diameters derived from the testing of 160 pneumococcal isolates. NCCLS MIC and disk diffusion interpretive breakpoints are indicated by double horizontal and vertical lines, respectively, on each graph (except for clinafloxacin, which currently lacks approved breakpoints). The fluoroquinolone agents tested in this study included ofloxacin (A), levofloxacin (B), sparfloxacin (C), grepafloxacin (D), trovafloxacin (E), and clinafloxacin (F). Asterisks indicate ofloxacin-resistant strains.

TABLE 3.

Determination of interpretive error rates associated with NCCLS MIC and zone diameter breakpoints with isolates included in this studya

| Quinolone | MIC breakpoints (μg/ml)

|

Zone breakpoints (mm)

|

Error rates (no. [%])

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | R | I | S | VM | M | Minor | |

| Ofloxacin | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | ≤12 | 13–15 | ≥16 | 0 | 0 | 6 (3.7) |

| Levofloxacin | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | ≤13 | 14–16 | ≥17 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Sparfloxacin | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥2 | ≤15 | 16–18 | ≥19 | 3 (8.6) | 0 | 4 (2.5) |

| Grepafloxacin | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥2 | ≤15 | 16–18 | ≥19 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.9) |

| Trovafloxacin | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | ≤15 | 16–18 | ≥19 | 0 | 0 | 8 (5.0) |

Abbreviations: S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; VM, very major error; M, major error; Minor, minor error.

TABLE 4.

Alterations in GyrA, ParC, and ParE genes observed in isolates of S. pneumoniae demonstrating reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones

| Strain | Mutation(s)a in QRDR of:

|

MIC (μg/ml)b

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA | ParC | ParE | OFLX | LEVO | SPAR | GREP | TROV | CLFX | |||

| ATCC 49619 | Ser-81 | Ser-79 | Ser-80 | Asp-83 | Asp-435 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

| R6 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.12 |

| TN4201 | — | Phe | — | — | — | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| TN3659-6 | — | Phe | — | — | — | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 |

| F30078 | — | Tyr | — | — | — | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| F31324 | Phe | — | — | — | Asn | 16 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| F30084 | Phe | — | — | — | Asn | >16 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| J3810 | Phe | — | Pro | Tyr | — | >16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 |

| MD3904 | Phe | Phe | — | — | — | >16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 |

| CT5-5821 | Phe | Phe | — | — | — | >16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 |

Oligonucleotide primers for gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE were used to amplify gene fragments that included the QRDRs from the eight selected strains, isolate R6, and reference strain ATCC 49619. Amplification with oligonucleotide primers PNC6 and PNC7 produced the expected 232-bp gyrA fragment from each of the pneumococcal strains. Direct sequencing of the amplified gyrA gene fragments and alignment of the DNA sequences revealed a C-to-T mutation at the second position of the codon, resulting in an amino acid change of Ser-81 to Phe in five of the isolates, as shown in Table 4 (position numbers are based on the gyrA sequence of S. pneumoniae [1]). No mutations were detected in the gyrA gene fragment from strains TN3659-6, TN4201, or F30078, and no changes in gyrB were noted for any of the eight isolates.

The DNA sequences of the 329-bp parC gene fragments were aligned with the corresponding parC sequence from ATCC 49619. Five of the strains exhibited mutations in the Ser-79 codon, leading to substitutions with Phe (4 strains) or Tyr (1 strain) (Table 4; amino acid positions are based on those of the S. pneumoniae parC sequence [24]). Two mutations in the QRDR of the highly fluoroquinolone-resistant strain J3810 resulted in alterations of amino acids Ser-80 to Pro and Asp-83 to Tyr. No mutations were detected in the parC QRDR of the low-level-resistant strains F30084 or F31324.

Alignment of the 323-bp gene fragments of parE revealed mutations in pneumococcal isolates F30084 and F31324, resulting in the substitution of Asn for Asp-435 (position numbers are based on those of the S. pneumoniae parE sequence [24]). In both strains, the parE mutations were associated with Ser-81-to-Phe alterations of GyrA. The ParE sequences of the five remaining isolates were identical to those of R6 and the susceptible reference strain.

The strains highly resistant to ofloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin, and trovafloxacin expressed mutations in both the GyrA and ParC genes. For strains that possessed a single amino acid alteration in the ParC QRDR, the MICs were elevated but the isolates were not highly resistant to all of the newer fluoroquinolones. Double mutations involving GyrA and ParE resulted in higher MICs of ofloxacin and levofloxacin compared with those for the strains with a single amino acid change in ParC. Mutations in the gyrase A and topoisomerase IV genes did not have a pronounced effect on the susceptibilities of the study isolates to clinafloxacin (Fig. 1F).

DISCUSSION

This multicenter study has examined the in vitro activities of six contemporary fluoroquinolones against a collection of pneumococcal isolates, including 36 strains resistant to ofloxacin, that were recovered during recent active surveillance studies in North America, Belgium, and France. Our study was not designed to assess the incidence of such strains. However, resistance to ofloxacin occurred in 0.2% of isolates in the initial phase of the CDC North American surveillance study conducted from 1994 to 1996 (14), and resistance to levofloxacin was reported for 0.6% of isolates in a U.S. surveillance study conducted in 1996 and 1997 (29). Thus, while uncommon at the present time, the possibility exists that fluoroquinolone-resistant pneumococci will increase in frequency as these agents are used for treatment of community-acquired respiratory infections.

The newer fluoroquinolones included in the study showed improved activity over that observed with ofloxacin. As expected, levofloxacin, the active l isomer of ofloxacin, was approximately twofold more active than ofloxacin, although most strains that were resistant to ofloxacin were also resistant to levofloxacin (Fig. 1B). The rank order of activity of the newer agents on a weight basis against the ofloxacin-resistant strains was clinafloxacin (greatest) followed by trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, and then sparfloxacin. Two populations of strains were apparent when the activities of the latter three compounds against the strains were tested, i.e., those most resistant (MICs, ≥4 μg/ml) to grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin and those with lower-level resistance characterized by MICs two- to eightfold higher than those for the normal, susceptible population (Fig. 1C, D, and E). When representative strains with lower levels of resistance were characterized genetically, they exhibited mutations in either parC alone or gyrA and parE but not in gyrA or parC. In contrast, selected representatives of the highly fluoroquinolone-resistant strains proved to have mutations in both gyrA and parC (Table 4). These data are consistent with the descriptions of the first clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae which demonstrated low-level resistance to ciprofloxacin as a result of mutations in the parC gene (19). Additional isolates showing high-level resistance to ciprofloxacin had mutations in gyrA and parC (19). Further studies indicated that ParC was the preferential target of ciprofloxacin and that mutations in parC preceded mutations in gyrA (12, 13, 19, 23, 24, 26). In our study, the ofloxacin-resistant isolates showed ParC changes of Ser-79 to Phe or Tyr or Asp-83 to Gly or Tyr, analogous to the changes described for ciprofloxacin-resistant strains (12, 13, 19, 23, 24). The high-level ofloxacin-resistant isolates also showed GyrA alterations of Ser-81 to Phe or Tyr, as reported previously for ciprofloxacin-resistant strains, although on the basis of the numbering scheme used at that time for Staphylococcus aureus, the alteration was of Ser-84 (13, 19, 23, 26).

Susceptibility to sparfloxacin and trovafloxacin appears to be only modestly affected by the single parC mutations, as determined in prior reports (5, 12, 25) and in the present study. When sparfloxacin was the selecting agent, gyrA mutations were reported to precede alterations in parC (24). High-level resistance to both sparfloxacin and trovafloxacin was associated with double mutations involving both parC and gyrA (10, 23). When tested in vivo in a mouse pneumonia model, trovafloxacin was protective when the pneumococci used to initiate infection possessed a first-step parC mutation that resulted in a trovafloxacin MIC of 0.5 μg/ml (12). However, trovafloxacin was not effective in a mouse model of infection when the trovafloxacin MIC for the pneumococcal challenge strain was 4 μg/ml (4), which was similar to the MICs for strains with both parC and gyrA mutations in the present study.

An additional quinolone target site in pneumococci is parE, which encodes the second subunit of topoisomerase IV (26). An Asp-435-to-Asn alteration was associated with low-level resistance in first-step mutants selected with ciprofloxacin and with higher-level resistance when this parE mutation was associated with an additional mutation in gyrA (26). Two of our intermediate-level strains (F30084 and F31324) possessed gyrA mutations and lacked parC mutations but had the Asp-435-to-Asn mutation in ParE. These appear to be the first clinical isolates of pneumococci to be characterized with this mutation. In addition, strain J3810 demonstrated previously unreported ParC changes of Ser-80 to Pro and Asp-83 to Tyr, in addition to a GyrA alteration of Ser-81 to Phe (Table 4). The fluoroquinolone MICs for J3810 were similar to those for other highly resistant strains that express the previously described double mutations of gyrA and parC.

NCCLS interpretive breakpoints do not yet exist for clinafloxacin. However, the MICs of that agent did not exceed 1 μg/ml for the strains possessing the single or double mutations in the known fluoroquinolone targets affected by the other compounds. It is possible that the 8-chlorine substituent of the clinafloxacin structure (11) enhances its activity against both quinolone-susceptible and -resistant strains of pneumococci. However, further study may be required to understand the specific targets of clinafloxacin in S. pneumoniae.

Lastly, this study afforded an opportunity to compare the NCCLS MIC and zone diameter breakpoint criteria established for five of the agents (22). The NCCLS breakpoints most often characterized the single parC mutant strains or those with mutations in gyrA and parE as intermediate or borderline resistant to the newer fluoroquinolones, while the strains with mutations in gyrA and parC were generally characterized as frankly resistant (Fig. 1). The only exception is that the NCCLS breakpoints categorized the parC single mutants and the gyrA and parE double mutants as susceptible to trovafloxacin, even though the MICs of that agent were elevated in a manner similar to those for grepafloxacin and sparfloxacin (Fig. 1E). With the exception of some very major errors with sparfloxacin disk tests, the interpretive category error rates recorded in this study with the NCCLS breakpoints are similar to those observed with other agents (15) and indicate that testing of pneumococci can be performed reliably by either the NCCLS MIC or the disk diffusion procedure. It should be noted that the NCCLS breakpoints were established with several data sets in addition to the data presented here. If only our data were considered, it would seem reasonable to increase the sparfloxacin zone diameter breakpoints by 1 mm.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that clinical pneumococcal isolates with mutations in the QRDRs of both gyrA and parC are classified by the current NCCLS breakpoints as resistant to the newer fluoroquinolones included in this study. Isolates with only parC or parE and gyrA mutations are associated with borderline resistance (sparfloxacin and grepafloxacin) or elevated MICs (trovafloxacin) and diminished zone diameters that are proximate to the current interpretive category breakpoints. Clinical studies will be required to determine the significance of the reduced susceptibilities of the latter strains to the newer fluoroquinolones. It will also be important to monitor the susceptibilities of contemporary pneumococci to these agents as their use for the treatment of respiratory infections increases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Glaxo-Wellcome, Ortho-McNeil, Parke-Davis, Pfizer, Remel, and Rhône-Poulenc Rorer. The quinolone-resistant strains tested by MGH were graciously provided by the Centre National de Reference des Pneumocoques, Créteil, France, and André Bryskier, of Hoechst Marion Roussel, Inc., Romainville, France.

We thank Jean Spargo (MGH), Leticia McElmeel (UTHSC), and Sharon Crawford (UTHSC) for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balas D, Fernandez-Moreira E, DeLaCampa A G. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding the DNA gyrase A subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2854–2861. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2854-2861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Allen S D, Brown S D, Jorgensen J H, Tenover F C. In-vitro susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to the d- and l-isomers of ofloxacin: interpretive criteria and quality control limits. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:365–369. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry A L, Pfaller M A, Fuchs P C, Packer R R. In vitro activities of 12 orally administered antimicrobial agents against four species of bacterial respiratory pathogens from U.S. medical centers in 1992 and 1993. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2419–2425. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedos J-P, Rieux V, Bauchet J, Muffat-Joly M, Carbon C, Azoulay-Dupuis E. Efficacy of trovafloxacin against penicillin-susceptible and multiresistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a mouse pneumonia model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:862–867. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard L, Nguyen Van J-C, Mainardi J-L. In vivo selection of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to quinolones, including sparfloxacin. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1995;1:60–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breiman R F, Butler J C, Tenover F C, Elliott J, Facklam R R. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1831–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler J C, Hofmann J, Cetron M S, Elliott J A, Facklam R R, Breiman R F the Pneumococcal Sentinel Surveillance Working Group. The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s pneumococcal sentinel surveillance system. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:986–993. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doern G V, Brueggemann A, Holley H P, Jr, Rausch A M. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from outpatients in the United States during the winter months of 1994 to 1995: results of a 30-center national surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1208–1213. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feikin D, Cetron M, Schuchat A, Facklam R, Jorgensen J, Kolczak M Active Surveillance Team. Program and abstracts of the 35th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1997. Multistate population-based assessment of drug-resistant S. pneumoniae mortality. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein, F. W., J. F. Acar, and the Alexander Project Collaborative Group. 1996. Antimicrobial resistance among lower respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae; results of a 1992–1993 Western Europe and USA collaborative surveillance study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38(Suppl. A):71–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Gootz T D, Brighty K E. Fluoroquinolone antibacterials: SAR, mechanism of action, resistance, and clinical aspects. Med Res Rev. 1996;16:433–486. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199609)16:5<433::AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R, Haskell S, Schmieder B, Tankovic J, Girard D, Courvalin P, Polzer R J. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99, 219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2691–2697. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis M-D, Moreau N J, Gutmann L. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen J H, McElmeel M L, Crawford S A, Cetron M, Breiman R F. Program and abstracts of the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Streptogramin and fluoroquinolone resistance among recent North American isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, abstr. C84; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen J H, Swenson J M, Tenover F C, Ferraro M J, Hindler J A, Murray P R. Development of interpretive criteria and quality control limits for broth microdilution and disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2448–2459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2448-2459.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margerrison E E C, Hopewell R, Fisher L M. Nucleotide sequence of the Staphylococcus aureus gyrB-gyrA locus encoding the DNA gyrase A and B proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1596–1603. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1596-1603.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDougal L K, Rasheed J K, Biddle J W, Tenover F C. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moroney J, Fiore A, Farley M, Harrison L, Patterson J, Cetron M, Schuchat A. Program and abstracts of the 35th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1997. Therapy and outcomes of meningitis caused by drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP) in three U.S. cities, 1994–1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muñoz R, de la Campa A G. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighth informational supplement M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;40:471–474. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simor A E, Louie M, Low D E The Canadian Surveillance Network. Canadian national survey of prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2190–2193. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thornsberry C, Ogilvie P, Kahn J, Mauriz Y. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis in the United States in 1996–1997 respiratory season. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]