Abstract

The traditional method for analyzing the content of instant tea has disadvantages such as complicated operation and being time-consuming. In this study, a method for the rapid determination of instant tea components by near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy was established and optimized. The NIR spectra of 118 instant tea samples were used to evaluate the modeling and prediction performance of a combination of binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO) with support vector regression (SVR), BPSO with partial least squares (PLS), and SVR and PLS without BPSO. Under optimal conditions, Rp for moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides were 0.9678, 0.9757, 0.7569, and 0.8185, respectively. The values of SEP were less than 0.9302, and absolute values of Bias were less than 0.3667. These findings indicate that machine learning can be used to optimize the detection model of instant tea components based on NIR methods to improve prediction accuracy.

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

Instant tea utilizes the highest quantity of tea raw materials worldwide, and its consumption has increased rapidly in recent years1. The manufacturing process of instant tea primarily comprises extraction, filtration, vacuum concentration, and drying2. Instant tea maintains the nutritional characteristics and flavor of traditional tea. In addition, instant tea offers drinking convenience, has low amounts of pesticide residues, and is easy to transport. Consequently, it is popular among consumers and has a broad market prospect3. As consumers pay increasing attention to the quality of instant tea, its quality control has also become increasingly important4.

The quality of instant tea is determined by several main compounds, specifically moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides5. These compounds not only give the tea a unique taste, but also provide a variety of health benefits6. If the moisture content is too high, the instant tea can produce mildew, and consequently, its nutrition and flavor may change. Therefore, a specific moisture content limit should be maintained during the processing and storage of instant tea to ensure the stability of its quality7. Caffeine is an alkaloid with therapeutic effects on many diseases, including metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, liver diseases, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases8,9. Additionally, caffeine contributes a bitter taste to instant tea10. Tea polyphenols consist of four major groups: catechins, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and anthocyanins11. They have a variety of physiological effects, such as antioxidation, antiradiation, antiaging, hypoglycemic, and bacteriostatic effects12. The astringent and bitter taste of tea mainly results from tea polyphenols13. Tea polysaccharides, which are acidic, have health benefits, such as lowering blood sugar, blood lipids, and blood pressure; they also enhance the immune system and resistance to hypoxia14. Tea polysaccharides can weaken the bitter taste and astringency and alleviate the stimulating effect of tea15.

Currently, the conventional physical and chemical methods for determining the levels of moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides in instant tea mainly involve oven drying, spectrophotometry, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)16–19. Although techniques based on sizable equipment provide various reliable protocols with good accuracy and sensitivity, they usually suffer from shortcomings such as complicated pretreatment procedures, time-consuming operations, high cost, and a need for professional operators20. Therefore, optical spectroscopic techniques are increasingly used for the rapid, nondestructive assessment of food products21. Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is particularly attractive for this purpose. The NIR spectral region is mainly the frequency-doubled and combined-frequency absorption regions of the hydrogen-containing group X–H (X being an element such as O, N, S, or C). Because various organic substances contain different groups, and various groups have different absorption wavelengths for NIR light in different chemical environments, the NIR spectrum can be utilized to perform qualitative and quantitative analyses in food component analysis22. Since recent years, NIR spectroscopy is being applied in the prediction of tea composition23. It has been used to discriminate the roast green tea from different origins, estimate the fermentation degree of Pu'er tea in processing, quantitatively determine the contents of total polyphenols, caffeine, and catechins in tea leaves, and classify special-grade green tea. However, studies performing nondestructive quantitative analysis of biochemical components in instant tea are scant24.

In the multivariate data analysis step, the partial least squares (PLS) model is the most widely used model for the quantitative analysis of NIR spectroscopy. Support vector regression (SVR) is also a crucial quantitative analysis algorithm. In recent years, metaheuristic algorithms have been widely adopted as global optimizer methods25. The particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is one of these methods; it selects the feature subset, optimizes the model parameters, represents less overhead in operation, and has easier implementation and faster convergence during optimization than other metaheuristic algorithms26. Kennedy proposed PSO in 1995 and binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO) of discrete space in 199727. Combined with other classification algorithms, BPSO can obtain improved results.

In this study, we used BPSO respectively with SVR (BPSO–SVR) and PLS (BPSO–PLS) to enhance the randomness of the mutation after the reset mechanism and to keep the particle active in continuous optimization. In addition, a fast experiment for determining moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides in instant tea was carried out using different models. This study provides a reference for NIR spectroscopy combined with multivariate statistical analysis to determine food components.

Methods

Materials and instruments

A total of 118 varieties of instant tea were provided by Yunnan Tasly Deepure Tea Group Co., Ltd (Yunnan, China). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. These instant tea is a kind of fine powder solid tea product, which is processed by extracting and drying the tea as raw material. A caffeine standard was purchased from China Institute for Food and Drug Control; acetonitrile and ethanol were purchased from Merck Co., Ltd; phenol and concentrated sulfuric acid were purchased from Chinese Medicines Holdings Co., Ltd; and glucose was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., Ltd. Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals used were of analytical grade.

A U-3010 UV–Vis Hitachi spectrophotometer (Tokyo) was used to determine absorbance. An Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system was used to determine caffeine content. NIR spectrometry was carried out using a Thermo Fisher Antaris II (USA).

Determination of main components

The moisture content of the instant tea was determined according to ISO 7513:1990. The caffeine content was determined according to ISO 10727:2002 and the tea polyphenol content was determined according to ISO 14502-1:2005. The tea polysaccharide content was determined using a modified phenol–sulfuric acid method19.

Spectral data acquisition

NIR spectra were collected in reflectance mode. Each spectrum consisted of an average of 78 scans, in the range of 10,000–4000 cm−1. Before scanning, the instrument was fully preheated for more than half an hour. Three spectra were collected from each sample, and the average spectrum of the three spectra was taken as the original analytical spectrum of that sample. In this study, the spectral pretreatment method used was the standard normal variate transformation (SNV) method. This method removes physical spectral information resulting from particle size.

Correction set sample division

The acquired spectral data and the reference chemical data were separated into two sets: a calibration set and a prediction set. It has been reported that the tenfold cross-validation method, also called Rotation Estimation, is a practical method to statistically cut the data sample into smaller subsets. The advantage of this method is making full use of small sample data sets28. In this study, tenfold cross-validation was used to randomly select the prediction set, and the remaining samples were selected for the calibration set. In each execution, the model was trained using 90% of the data points and tested using the remaining 10%. Therefore, every data point was taken nine times for training and once for testing the model.

Chemometrics method

SVR

The SVR model is mainly used to realize linear regression by mapping spectral data to high-dimensional space and constructing a linear decision function in high-dimensional space29. A linear SVR classifier was trained based on the fitcsvm function in the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox™. Usually, a model selection procedure is required to determine the adjusting parameter C to improve the classification accuracy. Because the purpose of this study is to evaluate the search algorithm for spectral data selection, rather than the parameter selection for SVR classifiers, we adopted the default parameter value, i.e., C = 1.

PLS

PLS is an extensively used class of statistical methods that includes regression, classification, and dimension reduction techniques30. It uses latent variables, which are also called score vectors, to model the relationship between input and response variables. In the case of regression problems, PLS first generates the latent variables from the given data and uses them as new predictor variables. There are different types of PLS based on the techniques employed to extract the latent variables.

BPSO

The BPSO algorithm transforms the trajectories from a continuous space into discrete space and maintains a swarm of particles and a global best solution simultaneously. In BPSO, each bit only takes a value of “0” or “1,” and the velocities that affect particle positions are transformed into [0, 1] and a stochastic construction process is added to confirm the locations31.

Model evaluation

The performance of the final models was evaluated according to the root mean square error of calibration (RMSEC) and the root mean square error of the verification set (RMSEP). The optimal model method was chosen based on RMSEC and RMSEP as the index which were lower and close to each other. At the same time, the correlation coefficient of validation set (Rp), bias-corrected standard error of prediction (SEP) and Bias were used as auxiliary reference indexes for model evaluation32,33.

Software

Data processing and modeling analysis was carried out using MATLAB 2014a.

Results and discussion

Spectra investigation

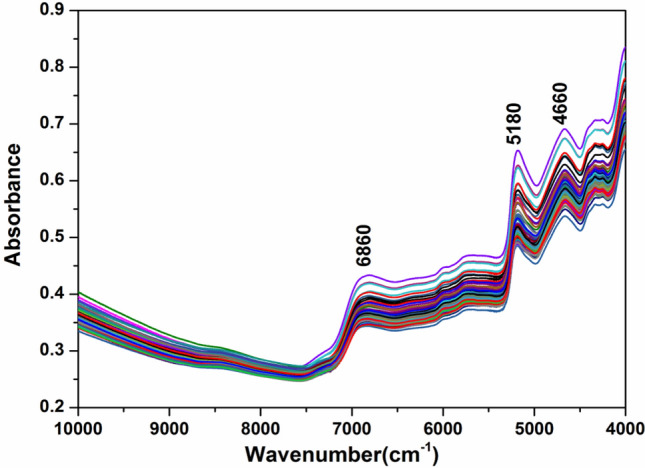

The original NIR spectra of the 118 instant tea samples are shown in Fig. 1. These spectra can reflect the intrinsic quality of the instant tea samples. The instant tea samples were similar in their type and place of production, and their NIR spectra were understandably similar as well. The first frequency-doubling peak of the N–H bond stretching vibration was at 6860 cm−1. The second frequency-doubling peak of the C=O stretching vibration was at 5180 cm−1, and the combined-frequency peak of the primary amine and tertiary amine stretching vibration was at 4660 cm−1 (Fig. 1). The spectral characteristics depend on the sample composition and provide a theoretical basis for the rapid prediction of moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharide contents.

Figure 1.

Original near-infrared spectra of 118 instant tea samples.

Classification of sample sets and distribution of measured values

A quantitative analysis of moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides was carried out on the 118 samples. The results in Table 1 show that the ranges of moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharide content in the samples are 3.76–6.29%, 0.48–2.80%, 18.70–22.40%, and 18.00–24.50%, respectively. The tenfold cross-validation method was used to randomly select the prediction set, and the remaining samples were selected for the calibration set.

Table 1.

Sample composition content statistics.

| Index | Min% | Max% | Mean% | Standard deviation% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 3.76 | 6.29 | 4.79 | 0.60 |

| Caffeine | 0.48 | 2.80 | 1.69 | 1.65 |

| Tea polyphenols | 18.70 | 22.40 | 20.93 | 0.89 |

| Tea polysaccharides | 18.00 | 24.50 | 21.18 | 2.17 |

Modeling Results

It has been reported that BPSO algorithm based on the traditional machine learning algorithm have a positive impact on the results of the model prediction34.The BPSO method was used to optimize the parameter combination, obtain the best tenfold cross-validation accuracy, and establish the model with the strongest prediction ability. In the BPSO process, the relevant parameters were set as follows: the swarm size was 20, the learning factors C1 and C2 were 2, the maximum evolutionary algebra was 100, and the weight parameter |Vmax| = 6. The results in Table 2 show that the SVR, BPSO–SVR, PLS, and BPSO–PLS models could predict the moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides of instant tea. The results showed that RMSEC and RMSEP presented a lower value by BPSO algorithm than those by SVR and PLS alone, which indicate that the addition of BPSO algorithm can improve the accuracy of model prediction. In addition, based on RMSEC and RMSEP, most of algorithm values between the calibration set and the prediction set in BPSO-PLS model were lower than those in BPSO-SVR model, and the range of SEP and Bias values were reasonable, which showed that BPSO-PLS model was stable.

Table 2.

Comparison of quantitative models for moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides in instant tea.

| Component | Modeling method | Rc | RMSEC | RP | RMSEP | SEP | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | SVR | 0.9852 | 1.3512 | 0.9028 | 1.0117 | 0.3297 | − 0.4412 |

| BPSO–SVR | 0.9884 | 1.189 | 0.9710 | 0.6670 | 0.3350 | − 0.1934 | |

| PLS | 0.9552 | 2.0706 | 0.9419 | 0.8123 | 0.1880 | − 0.1264 | |

| BPSO–PLS | 0.9983 | 0.4128 | 0.9678 | 0.6293 | 0.2230 | − 0.2272 | |

| Caffeine | SVR | 0.9909 | 1.105 | 0.8514 | 1.2096 | 0.3076 | 0.0619 |

| BPSO–SVR | 0.9916 | 1.0792 | 0.9610 | 0.6728 | 0.1548 | 0.0056 | |

| PLS | 0.9661 | 1.714 | 0.9596 | 0.6205 | 0.2484 | 0.1017 | |

| BPSO–PLS | 0.9981 | 0.4145 | 0.9757 | 0.5114 | 0.2647 | 0.1027 | |

| Tea polyphenols | SVR | 0.9579 | 2.8418 | 0.6482 | 2.3088 | 1.0408 | − 0.9307 |

| BPSO–SVR | 0.9594 | 2.8273 | 0.7948 | 2.0272 | 0.7084 | − 0.5186 | |

| PLS | 0.7391 | 6.1777 | 0.7022 | 2.1779 | 0.6531 | − 0.4879 | |

| BPSO–PLS | 0.9960 | 0.8191 | 0.7569 | 2.1082 | 0.7233 | − 0.3667 | |

| Tea polysaccharides | SVR | 0.9438 | 7.2186 | 0.6621 | 4.8339 | 0.8461 | 0.1784 |

| BPSO–SVR | 0.9465 | 7.1464 | 0.8040 | 4.1831 | 0.8090 | − 0.0615 | |

| PLS | 0.7804 | 13.0553 | 0.7558 | 4.5883 | 0.8207 | − 0.3354 | |

| BPSO–PLS | 0.9954 | 2.0187 | 0.8185 | 4.3109 | 0.9302 | − 0.0980 |

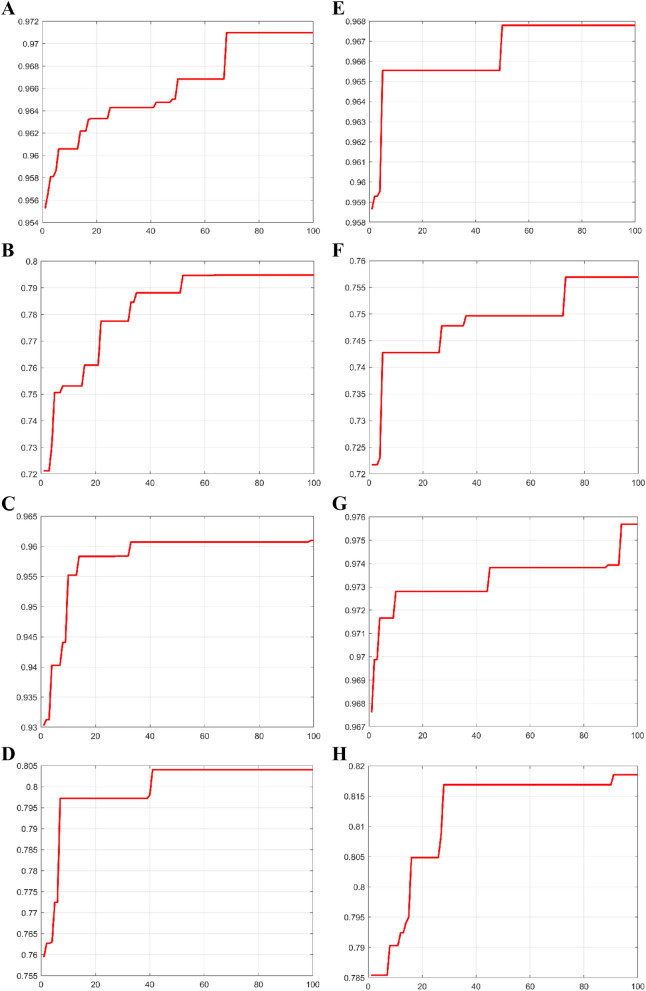

Figure 2 shows the convergence curve of the BPSO algorithm with the best results during the 100 runs. The model shows a large fluctuation at the beginning of the iteration, after which it decays with a small trend.

Figure 2.

(A–D) Parameter optimization results of the SVR model based on BPSO with fitness value versus number of iterations: (A) moisture, (B) caffeine, (C) tea polyphenols, and (D) tea polysaccharides. (E–H) Parameter optimization results of the PLS model based on BPSO with fitness value versus number of iterations: (E) moisture, (F) caffeine, (G) tea polyphenols, and (H) tea polysaccharides.

The BPSO–PLS model showed the most stable comprehensive performance and the most accurate prediction results for moisture. The values obtained for Rc, RMSEC, Rp, and RMSEP were 0.9983, 0.4128, 0.9678, and 0.6293, respectively. Comparing the four models and convergence curves for caffeine, the BPSO–PLS model had the most stable comprehensive performance and the most accurate prediction results; the Rc, RMSEC, Rp, and RMSEP were 0.9981, 0.4145, 0.9757, and 0.5114, respectively. For tea polyphenols, using the BPSO feature selection algorithm, R showed a significant improvement.The Rc, RMSEC, Rp, and RMSEP were 0.9960, 0.8191, 0.7569, and 2.1082, respectively. For tea polysaccharides models, using the BPSO feature selection algorithm, R also showed a significant improvement. The BPSO–PLS model had the most stable comprehensive performance and the most accurate prediction results for tea polysaccharides, and the Rc, RMSEC, Rp, and RMSEP were 0.9954, 2.0187, 0.8185, and 4.3109, respectively.

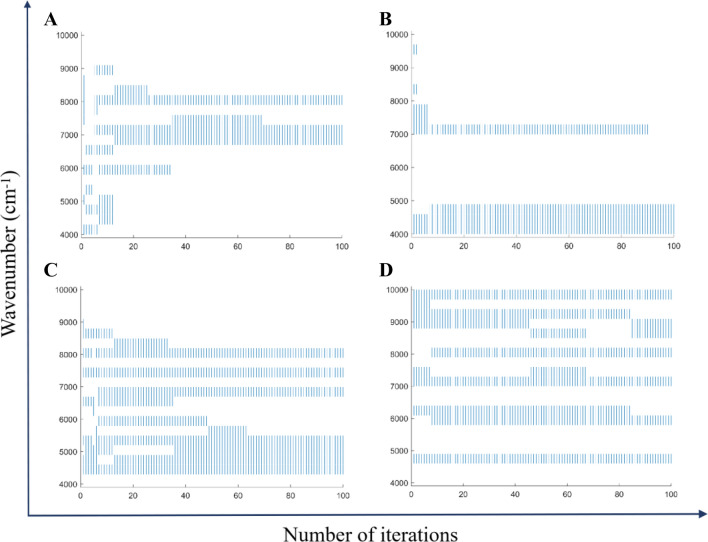

A spectral range was set, such that if it was selected more than 50 times, then this range was the final selected result. The process of selecting the wavenumber of the four components, resulting from 100 iterations, is shown in Fig. 3. We divided the spectral range into 20 segments with the same width of 311, and the last segment with a width of 319. From the wavenumber, we found that the spectral ranges selected for moisture and caffeine were relatively concentrated, while those for tea polyphenols and tea polysaccharides were relatively scattered.

Figure 3.

Wavenumber selection results of the four components: (A) moisture, (B) caffeine, (C) tea polyphenols, (D) tea polysaccharides.

Table 3 shows the results of selecting the wavenumber of the four components: moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides. The characteristic bands of water in instant tea were mainly concentrated in the two wavebands of 6694–7293 and 7892–8193 cm−1. The first-order frequency doubling of O–H stretching vibration in pure water is about 7143 cm−1, and the combined frequency absorption was 8197 cm−1,35. The characteristic band of the moisture in instant tea associated with compounds containing O–H group through hydrogen bond in various forms, and further make a shift of the absorption peak in the direction of long and short wavelengths. The characteristic bands of caffeine were concentrated in 4000–4894 and 6994–7293 cm−1. Near 4610 cm−1 was the combined frequency peak of stretching vibration from primary amine and tertiary amine36. In addition, the characteristic bands of instant tea polyphenols were concentrated in 4295–5494, 6694–6994, 7293–7593, and 7893–8193 cm−1. 4662 cm−1 was the second-order frequency doubling caused by C–C stretching vibration. Near 5000 cm−1 was the combined frequency of free O–H stretching vibration in phenols37. 6782–6894 cm−1 was the first-order frequency doubling of O–H. The characteristic bands of tea polysaccharides in instant tea were mainly concentrated in 4595–4894, 5794–6394, 7001–7293, 7893–8212, 8793–9393, 9692–10,000 cm−1. Near 4631 cm−1 was the combined frequency absorption peak of the primary amine group, and 4779 cm-1 indicated the presence of acyl group. 5333–6154 cm−1 was the third-order frequency doubling generated by C–C stretching vibration. The 5714–6667 cm−1 range was the vibration region of the amide and carbonyl groups. 6667–8333 cm−1 range was the absorption region of protein. The mixed vibration absorption region of fatty acids and polysaccharides was in the range of 8333–10,000 cm−1,38.

Table 3.

Results of selected NIR wavenumber of the four components: moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides.

| Component | Wavenumber (cm−1) |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 6694–7293, 7892–8193 |

| Caffeine | 4000–4894, 6994–7293 |

| Tea polyphenols | 4295–5494, 6694–6994, 7293–7593, 7893–8193 |

| Tea polysaccharides | 4595–4894, 5794–6394, 7001–7293, 7893–8212, 8793–9393, 9692–10,000 |

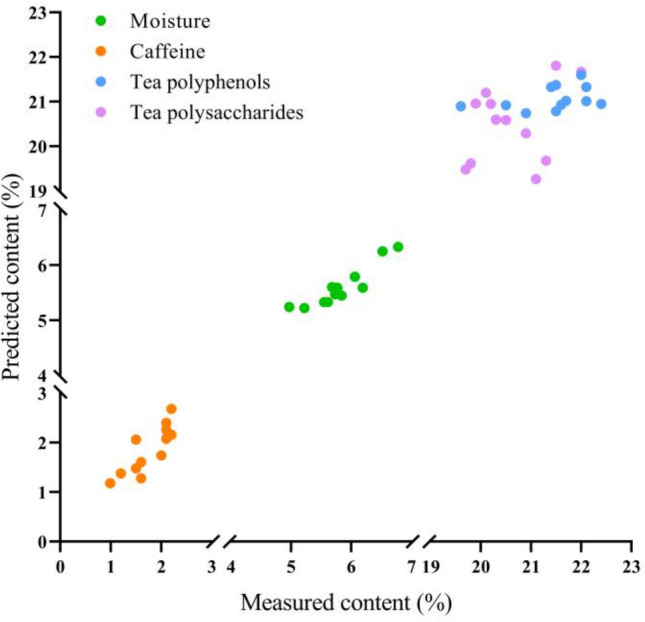

The scatter plots of 4 components between actual and NIR predicted values were shown in Fig. 4. It is well known that scatter plots present the relationship between two variables in two-dimensional coordinates, which can be used to evaluate the predictive ability of the model. In this study, the scatter points of moisture and caffeine between actual and predicted NIR values were concentrated and close to the diagonal. few scatter points of tea polyphenols and tea polysaccharides are relatively departed from the diagonal due to the complex structure. Taken together, the results indicate that the model exhibits a high prediction accuracy.

Figure 4.

Scatter plots of four components in instant tea samples between actual and predicted NIR values. Orange dots present caffeine, green dots present moisture, blue dots present tea polyphenols, and purple dots present tea polysaccharides.

Conclusions

In this study, a rapid NIR method to estimate the moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharide contents of instant tea was developed using different model calibrations. The tenfold cross-validation method was used to randomly select the prediction set, and BPSO was employed as the optimization algorithm for SVR and PLS. The results show that the Rp is above 0.9 for moisture and caffeine, and the Rp is approximately 0.8 for tea polyphenols and tea polysaccharides. Therefore, these models exhibited high precision and accuracy. This approach provides, for the first time, a fast, specific, and easily automatable method for the quantitative detection of moisture, caffeine, tea polyphenols, and tea polysaccharides in instant tea samples. This will enable the development of online compositional analysis techniques for more effective process management and quality control.

Author contributions

X.B. was involved in conceptualization, methodology development, validation, data curation, and writing, reviewing, and editing of the original draft. L.Z. assisted with formal analysis, methodology development, and software usage. C.K. and B.Q. contributed to data curation, formal analysis, and methodology development. Y.Z., X.Z. and J.S. involved in validation, supervision, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript. T.X and M.W. helped with acquiring resources, project administration, and supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072203), Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (TSBICIP-KJGG-016), Tianjin Science and Technology Commission (S21JD1002), and Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (TD13-5013).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaoli Bai and Lei Zhang.

Contributor Information

Ting Xia, Email: xiating@tust.edu.cn.

Min Wang, Email: minw@tust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pelvan E, Ozilgen M. Assessment of energy and exergy efficiencies and renewability of black tea, instant tea and ice tea production and waste valorization processes. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2017;12:59–77. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2017.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du LP, et al. Characterization of the volatile and sensory profile of instant Pu-erh tea using GC x GC-TOFMS and descriptive sensory analysis. Microchem. J. 2019;146:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2019.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang T, et al. Suppressive interaction approach for masking stale note of instant ripened Pu-Erh tea products. Molecules. 2019;24:13. doi: 10.3390/molecules24244473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, et al. Anti-obesity effects of instant fermented teas in vitro and in mice with high-fat-diet-induced obesity. Food Funct. 2019;10:3502–3513. doi: 10.1039/C9FO00162J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang QP, et al. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of a high-theabrownins instant Pu-erh tea produced using Aspergillus tubingensis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018;90:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu MZ, Li N, Zhao M, Yu WL, Wu JL. Metabolomic profiling delineate taste qualities of tea leaf pubescence. Food Res. Int. 2017;94:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, et al. Research on moldy tea feature classification based on WKNN algorithm and NIR hyperspectral imaging. Spectroc. Acta Pt. A-Mol. Biomolec. Spectr. 2019;206:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platt DE, et al. Caffeine impact on metabolic syndrome components is modulated by a CYP1A2 variant. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016;68:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000441481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer LA, Hixon ML. Review of animal studies on the cardiovascular effects of caffeine. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;118:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C, et al. Application of metabolomics profiling in the analysis of metabolites and taste quality in different subtypes of white tea. Food Res. Int. 2018;106:909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerio LC, Wachira FN, Wanyoko JK, Rotich MK. Total polyphenols, catechin profiles and antioxidant activity of tea products from purple leaf coloured tea cultivars. Food Chem. 2013;136:1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah T, Shaikh F, Ansari S. To determine the effects of green tea on blood pressure of healthy and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) individuals. J. Liaquat Univ. Med. Health. 2017;16:200–204. doi: 10.22442/jlumhs.171640533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury A, Sarkar J, Chakraborti T, Pramanik PK, Chakraborti S. Protective role of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in health and disease: A perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016;78:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du LL, et al. Tea polysaccharides and their bioactivities. Molecules. 2016;21:18. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu FF, et al. The new insight into the influence of fermentation temperature on quality and bioactivities of black tea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020;117:7. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei YZ, et al. Visual detection of the moisture content of tea leaves with hyperspectral imaging technology. J. Food Eng. 2019;248:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren GX, Xue P, Sun XY, Zhao G. Determination of the volatile and polyphenol constituents and the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of the bioactive compounds from the by-product of Rosa rugosa Thunb. var. plena Regal tea. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;18:9. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2374-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae IK, Ham HM, Jeong MH, Kim DH, Kim HJ. Simultaneous determination of 15 phenolic compounds and caffeine in teas and mate using RP-HPLC/UV detection: Method development and optimization of extraction process. Food Chem. 2015;172:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xi XG, Wei XL, Wang YF, Chu QJ, Xiao JB. determination of tea polysaccharides in Camellia sinensis by a modified Phenol-sulfuric acid method. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2010;62:671–678. doi: 10.2298/ABS1003669X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li JJ, et al. Discrimination of Chinese teas according to major amino acid composition by a colorimetric IDA sensor. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 2017;240:770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra P, et al. Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging for non-destructive classification of commercial tea products. J. Food Eng. 2018;238:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alishahi A, Farahmand H, Prieto N, Cozzolino D. Identification of transgenic foods using NIR spectroscopy: A review. Spectroc. Acta Pt. A-Mol. Biomol. Spectr. 2010;75:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firmani P, De Luca S, Bucci R, Marini F, Biancolillo A. Near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy-based classification for the authentication of Darjeeling black tea. Food Control. 2019;100:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, et al. Quality assessment of instant green tea using portable NIR spectrometer. Spectrochim. Acta A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020;240:118576. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei JX, et al. A BPSO-SVM algorithm based on memory renewal and enhanced mutation mechanisms for feature selection. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2017;58:176–192. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2017.04.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang FR, et al. Detection of adulteration in Chinese honey using NIR and ATR-FTIR spectral data fusion. Spectroc. Acta Pt. A-Mol. Biomol. Spectr. 2020;235:8. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdez F, Vazquez JC, Melin P, Castillo O. Comparative study of the use of fuzzy logic in improving particle swarm optimization variants for mathematical functions using co-evolution. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2017;52:1070–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2016.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez JD, Pérez A, Lozano JA. Sensitivity analysis of kappa-fold cross validation in prediction error estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010;32:569–575. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos CED, Sampaio RC, Coelho LD, Bestard GA, Llanos CH. Multi-objective adaptive differential evolution for SVM/SVR hyperparameters selection. Pattern Recognit. 2021;110:10. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2020.107649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genisheva Z, et al. New PLS analysis approach to wine volatile compounds characterization by near infrared spectroscopy (NIR) Food Chem. 2018;246:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan KZ, Wang SW, Song YZ, Liu Y, Gong ZP. Estimating nitrogen status of rice canopy using hyperspectral reflectance combined with BPSO-SVR in cold region. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2018;172:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2017.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YG, et al. Rapid determination of lycium barbarum polysaccharide with effective wavelength selection using near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Food Anal. Methods. 2016;9:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s12161-015-0178-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhanga CH, et al. Rapid analysis of polysaccharides contents in Glycyrrhiza by near infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;79:983–987. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y, et al. Remote sensing of water quality based on HJ-1A HSI imagery with modified discrete binary particle swarm optimization-partial least squares (MDBPSO-PLS) in inland waters: A case in Weishan Lake. Ecol. Inform. 2018;44:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cozzolino D, et al. Effect of temperature variation on the visible and near infrared spectra of wine and the consequences on the partial least square calibrations developed to measure chemical composition. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007;588:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baykal D, et al. Nondestructive assessment of engineered cartilage constructs using near-infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2010;64(10):1160. doi: 10.1366/000370210792973604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeuchi M, et al. Near infrared study on the adsorption states of NH3 and NH4 + on hydrated ZSM-5 zeolites. J. Near Infrared Spec. 2019;27(3):096703351983662. doi: 10.1177/0967033519836622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad PSR, Sarma LP. A near-infrared spectroscopic study of hydroxyl in natural chondrodite. Am. Mineral. 2004;89(7):1056–1060. doi: 10.2138/am-2004-0717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]