Abstract

Combining artemisinin or a derivative with mefloquine increases cure rates in falciparum malaria patients, reduces transmission, and may slow the development of resistance. The combination of artesunate, given for 3 days, and mefloquine is now the treatment of choice for uncomplicated multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria acquired on the western or eastern borders of Thailand. To optimize mefloquine administration in this combination, a prospective study of mefloquine pharmacokinetics was conducted with 120 children (4 to 15 years old) with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria, who were divided into four age- and sex-matched groups. The patients all received artesunate (4 mg/kg of body weight/day orally for 3 days and mefloquine as either (i) a single dose (25 mg/kg) on day 2 with food, (ii) a split dose (15 mg/kg on day 2 and 10 mg/kg on day 3) with food, (iii) a single dose (25 mg/kg) on day 0 without food, or (iv) a single dose (25 mg/kg) on day 2 without food. Delaying administration of mefloquine until day 2 was associated with a mean (95% confidence interval) increase in estimated oral bioavailability of 72% (36 to 109%). On day 2 coadministration with food did not increase mefloquine absorption significantly, and there were no significant differences between patients receiving split- and single-dose administration. In combination with artesunate, mefloquine administration should be delayed until the second or third day after presentation.

Mefloquine was first introduced for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand in 1984. It is a quinoline methanol compound available only for oral administration. Mefloquine is cleared slowly from the body, with an elimination half-life of ∼2 weeks in antimalarial treatment (6). Although a single dose of 15 mg of base/kg of body weight initially gave cure rates in excess of 90% on the western and eastern borders of Thailand, the efficacy of this regimen declined rapidly after 1990, and the recommended dose was increased to 25 mg/kg (17). Recent studies have shown that splitting the dose of mefloquine into 15 and 10 mg/kg (at least 8 h apart) halves the rate of early vomiting (20), and nearly doubles the mean blood concentrations on the third day following treatment (which correspond approximately to peak levels) (18). Since vomiting and postabsorptive blood levels are major determinants of treatment outcome (16), these data argue in favor of splitting the dose of mefloquine when given alone for the treatment of malaria. In contrast two smaller studies have compared split- and single-dose mefloquine regimens in healthy volunteers and found no difference in the overall bioavailability of mefloquine (4, 9). There may also be some benefit in giving mefloquine with food. Mefloquine is a hydrophobic lipophilic compound. Absorption is increased by buffering stomach acidity and coadministering fats to improve solubility. In healthy volunteers mefloquine was absorbed more rapidly, the peak concentration was 1.7 times higher, and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve was 1.4 times greater when mefloquine was taken after food compared to after an overnight fast (1, 2). The relevance of these observations to the treatment of malaria is unclear. Furthermore, the majority of pharmacokinetic data on mefloquine comes from studies in adults, whereas the majority of antimalarial treatments worldwide are given to children.

By mid-1994 on the Thai-Burmese border cure rates with high-dose mefloquine alone had fallen to nearly 50%. Mefloquine monotherapy for uncomplicated falciparum malaria was discontinued and replaced by a combination of 3 days of artesunate and mefloquine (25 mg/kg) (12). Combinations of artemisinin or a derivative with mefloquine are associated with more rapid treatment responses, increased cure rates, and lower transmission potential and may slow the development of mefloquine resistance (13, 21, 22). There is now increasing acceptance that mefloquine should not be employed alone and should only be used in combination with artemisinin or one of its derivatives. Coadministration of an artemisinin derivative has been reported to alter mefloquine pharmacokinetics (5), although this is probably a secondary result of the more rapid clinical improvement rather than a direct interaction. In order to optimize dosing in the artesunate-mefloquine regimen and define the variance in blood concentration profiles between patients, we have conducted a large study of children with acute falciparum malaria to investigate the pharmacokinetic consequences of splitting the dose, administering the drug during recovery (compared with on admission), and giving a small fatty meal with mefloquine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

This trial was conducted from May 1994 to October 1995 in Shoklo, Mae Sod, Thailand, a camp for displaced persons of the Karen ethnic minority. The camp is situated along the western border of Thailand in an area of seasonal and low malaria transmission (8).

Patients.

Children between 4 and 15 years with slide-confirmed falciparum malaria were eligible to be enrolled in the study if they and their parents gave informed consent. Children who had received antimalarial medication in the preceding 63 days, had a parasitemia of >4%, weighed <5 kg, or had signs of severity (23) or concomitant disease requiring hospital admission were all excluded. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, and by the Karen Refugee Committee, Mae Sod, Thailand.

Antimalarial drug regimens.

A total of 120 children were recruited from the outpatient treatment clinic into four sets of 30 age- and sex-matched patients. As each eligible patient presented their treatment allocation was determined from a randomized sequence. This resulted in 30 age- and sex-matched quartets, in which each patient received one of the four drug regimens described below. All patients received 4 mg of artesunate (Guilin no. 1 factory, Guangxi, People’s Republic of China)/kg/day for 3 days and were allocated to receive mefloquine (Lariam [250 mg base tablets]; Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in one of the four following regimens: (i) group A, a single dose of mefloquine (25 mg/kg) on day 2 given with food; (ii) group B, a 15-mg/kg dose of mefloquine on day 2 and a 10-mg/kg dose of mefloquine on day 3 (both doses given with food); (iii) group C, a single dose of mefloquine (25 mg/kg) given on day 0 without food; and (iv) group D, a single dose of mefloquine (25 mg/kg) given on day 2 without food.

The two groups receiving their medication with food (groups A and B) were given three biscuits (containing in total ∼15 g of fat) and two glasses of water to take with their mefloquine. A group with food administration on day 0 was not included, as children are usually reluctant to eat when ill with acute malaria. The children in groups C and D received the same dose of mefloquine as children in groups A and B, but the former were given crushed mefloquine tablets mixed with water and given by spoon or syringe but without food. Drug administration was observed in all cases. Any child vomiting the medication within 1 h of drug administration was excluded from the study and a new patient was recruited into the set to replace the excluded child. Once excluded, patients were given a repeat full dose of mefloquine, if vomiting occurred in less than 30 min, or half the dose, if vomiting occurred between 30 and 60 min, and standard treatment was completed thereafter.

Study procedures.

On admission a questionnaire was completed, recording details of symptoms and their duration and the history of previous antimalarial medication (since health structures in the camp are the only source of antimalarial drugs in this area, the history is usually a reliable guide to pretreatment). A full clinical examination was made, and blood was taken for blood film, hematocrit, and leukocyte count procedures. Parasite counts were determined on Giemsa-stained thick films as the number of parasites per 500 leukocytes. Patients were examined daily thereafter until they became aparasitemic and then were seen weekly for 9 weeks. At each clinic appointment, a full physical examination was performed and the symptom questionnaire was completed, and at the weekly visits, blood was taken for hematocrit and parasite count procedures. Fever was defined as an oral temperature of ≥37.5°C.

Whole capillary blood (400 μl) was collected by finger prick on days 0, 3, 5, 7, 9, 14, and 28 following the start of antimalarial treatment. Samples were collected in the morning between 0800 and 1100 h, and the exact time was noted for samples within the first week. In group C, an extra sample was also taken on day 1, 24 h following the single-dose administration on day 0 of mefloquine (25 mg/kg). Heparinized blood samples were stored at −20°C locally and then were transported on dry ice to Bangkok, Thailand, where they were stored at −70°C until analysis. Whole-blood mefloquine levels are stable for at least 4 years under these conditions (unpublished observations).

Drug assays.

Whole-blood mefloquine levels were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection. Quantitation of mefloquine was performed by reversed-phase chromatography with isocratic elution and an internal standard procedure. Mefloquine was extracted by liquid-liquid extraction into a dichloromethane layer, which was separated from the aqueous phase, evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted in mobile phase before injection into the high-performance liquid chromatography column (13). Whole (capillary)-blood samples (0.2 ml) were diluted with distilled water (1:1) before the assay. The assay was linear over 0.05 to 4 μg/ml. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation for the capillary whole-blood assays were 4.5% for concentrations between 500 and 2,000 ng/ml. The limit of detection was 50 ng/ml. At this study site capillary blood samples have been shown to give equivalent results to larger-volume venous blood samples (19).

Pharmacokinetics.

Five main outcome measures were chosen prospectively to describe the kinetics of mefloquine. These were the observed maximum whole-blood concentration (Cmax), which was read directly from the individual whole-blood concentration-time data; the terminal elimination half-life (t1/2), which was calculated by dividing ln2 by λZ (the terminal elimination rate constant); the area under the whole blood concentration-time curve extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞); the apparent volume of distribution (V/f); and the apparent oral clearance per fraction of drug absorbed (CL/f). CL/f was estimated from the ratio of the dose to AUC0–∞, and V/f was estimated from CL/f divided by λZ. The terminal elimination rate constant was calculated by fitting the individual data from the terminal phase of the concentration-time plots to log-linear regression by using the method of least squares. The AUC0–∞ for each individual was derived from the time of drug administration to the time of the last measurable concentration by using the linear trapezoidal rule. Extrapolation to infinity was determined by dividing the last measurable concentration level by λZ. Each measure was calculated separately for each subject and calculated from the time of mefloquine administration instead of the day of admission by using noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analysis (WinNonlin, standard edition version 1.1; Scientific Consulting Inc., Apex, N.C.). Without day 28 levels the precision of the estimate of λZ is reduced, and since this parameter is required for the calculation of V/f, CL/f, t1/2, and AUC0–∞ it was decided to only calculate these parameters for patients for whom day 28 levels were available.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by using SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

Normally distributed data were described by means and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and compared by using Student’s t test. Abnormally distributed data were described by median, range, and interquartile range, and the four treatment groups were compared by using the Kruskal-Wallis test. For categorical variables, percentages and corresponding 95% CI were calculated, and the χ2 test was used for comparison among the four treatment groups. Wilcoxon’s test for paired observations was performed to assess the statistical significance of the differences of the pharmacokinetic parameters for the following three main comparisons: single dose versus split dose (group A versus group B), giving the drug in the acute phase of malaria versus during the convalescent phase (group C versus group D), and giving the drug with food versus without food (group A versus group D). The association between two continuous variables was assessed by using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical and laboratory findings.

Overall, 120 patients were recruited into the study and received a complete course of treatment. Of these, 10 were excluded from analysis; 2 were found to have vivax malaria, 3 had significant pretreatment mefloquine levels (>150 ng/ml) from an undeclared previous treatment, 1 had only three samples taken, and for 4 all samples were lost. On admission all of the patients were symptomatic, and 71 (65%) were febrile. The geometric mean parasitemia upon presentation was 6,988 (95% CI, 4,763 to 10,251) μl−1. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 728 (91%) samples out of the 797 planned were collected. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics or compliance between groups. For 14 subjects (13%) (1 in group A, 3 in group C, and 5 each in groups B and D), the sample on day 28 was not collected, which precluded analysis of the AUC0–∞ and related pharmacokinetic parameters. All patients responded rapidly to treatment, and none developed complications. By day 2 only one (1%) patient was still parasitemic, and five (5%) were still febrile (all with oral temperatures between 37.5 and 38°C). Three patients had recrudescent parasitemia by day 42 of follow-up (one each in groups B, C, and D). All were re-treated successfully with a 7-day regimen of artesunate.

TABLE 1.

Admission characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Group

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| No. of subjects enrolled | 27 | 29 | 27 | 27 |

| No. of males (%) | 16 (59) | 18 (62) | 16 (59) | 15 (56) |

| Mean age (SD) (yr) | 9.0 (2.2) | 9.4 (2.8) | 9.6 (2.9) | 9.2 (2.9) |

| Range of ages (yr) | 5–13 | 5–15 | 4–15 | 14–41 |

| Mean wt (SD) (kg) | 24.9 (8.7) | 25.3 (8.7) | 25.8 (8.1) | 26.0 (7.8) |

| Mean temp (SD) (°C) | 38.5 (0.9) | 38.4 (1.1) | 38.4 (0.8) | 38.7 (1.1) |

| No. (%) of febrile subjectsb | 17 (63) | 17 (59) | 17 (63) | 20 (74) |

| Mean hematocrit (SD) (%) | 36.2 (3.9) | 36.5 (3.5) | 36.2 (4.6) | 35.5 (4.9) |

| No. (%) of subjects with hematocrit of <30% | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (16) |

| Geometric mean parasite count per μl of blood (95% CI) | 6,788 (3,003–15,344) | 7,458 (3,687–15,084) | 4,843 (1,949–12,035) | 9,677 (4,499–20,816) |

Overall, there was no difference between treatment groups.

Temperature of ≥37.5°C.

Mefloquine pharmacokinetics.

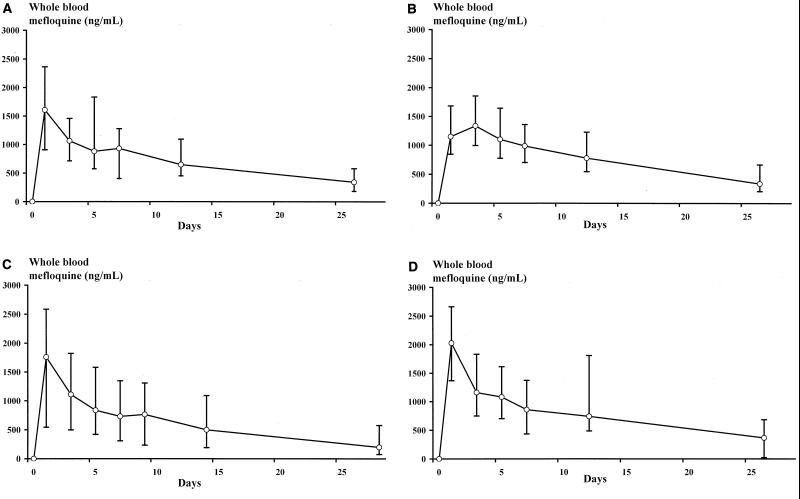

A summary of mefloquine pharmacokinetics is given in Table 2. The mean (95% CI) actual times between the first administration of mefloquine and the subsequent blood samples are shown in Table 3. Whole-blood mefloquine concentrations during follow-up in each of the treatment groups are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, the median (range) Cmax of mefloquine was 1,606 (422 to 4,137) ng/ml, the AUC was 25,589 (6,441 to 73,716) ng/ml · day, the V/f was 18.1 (5.5 to 60.7) liters/kg, the t1/2 was 12.5 (6.5 to 33.2) days, and the CI/f was 0.98 (0.34 to 3.88) liters/kg/day. The λZ was always estimated on the basis of at least three data points. Visual inspection of the individual log-linear plots of mefloquine levels against time with the fitted regression equations showed good agreement between the observed and predicted mefloquine levels. R2 was found to be >80% in 88% (85 of 97) of the cases. The estimates of the t1/2 were not significantly different among the four groups. The distribution of values was log normal, with an overall geometric mean t1/2 value of 13 days (95% CI, 12.2 to 14.0 days; n = 96). Thus, it would be expected that 10% of patients, similar to those in the present study, would show t1/2 values of >20.5 days and 10% would show t1/2 values of <8.4 days.

TABLE 2.

Mefloquine pharmacokinetics in the presence of artesunatea

| Parameter | Group

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 1,614 (710–2,881) (n = 27) | 1,377 (838–3,106) (n = 29) | 1,757 (422–3,051) (n = 27) | 1,962 (809–4,137) (n = 27) |

| AUC (ng/ml · day) | 25,322 (7,936–49,354) (n = 26) | 28,654 (17,827–53,788) (n = 25) | 21,750 (6,441–52,491) (n = 24) | 28,196 (19,133–73,716) (n = 22) |

| CI/f (liters/kg/day) | 0.98 (0.51–3.15) (n = 26) | 0.87 (0.46–1.40) (n = 25) | 1.15 (0.48–3.88) (n = 24) | 0.89 (0.34–1.31) (n = 22) |

| V/f (liters/kg) | 18.5 (8.2–41.6) (n = 26) | 18.1 (6.2–30.5) (n = 25) | 18.8 (11.3–60.7) (n = 24) | 17.5 (5.5–28.1) (n = 22) |

| t1/2 (days) | 13.6 (8.2–31.3) (n = 26) | 12.9 (7.9–30.7) (n = 25) | 11.6 (6.9–16.6) (n = 24) | 12.1 (6.5–33.2) (n = 22) |

| AUC above 500 ng/ml (ng/ml · day) | 6,037 (315–22,106) (n = 26) | 8,432 (2,379–33,738) (n = 25) | 5,303 (0–23,742) (n = 27) | 7,759 (4,540–39,693) (n = 22) |

| Time above 500 ng/ml (days) | 19 (3–26) (n = 27) | 23 (11–26) (n = 25) | 14 (0–26) (n = 27) | 22 (11–26) (n = 23) |

Median (range) and number of patients with available data.

TABLE 3.

Actual time between first administration of mefloquine and subsequent blood sampling

| Sample day (group[s]) | Time (h) between mefloquine administration and blood sampling

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Range | |

| 1 | 24.6 | 24.3–24.9 | 20.6–31.2 |

| 3 | 72.7 | 72.2–73.3 | 65.5–81.5 |

| 5 | 120 | 120–121 | 113–128 |

| 7 | 170 | 168–172 | 143–192 |

| 9 | 215 | 212–220 | 189–239 |

| 12 (A, B, and D) | 291 | 289–293 | 270–314 |

| 14 (C) | 341 | 335–347 | 330–387 |

| 26 (A, B, and D) | 632 | 627–637 | 579–745 |

| 28 (C) | 676 | 667–685 | 645–745 |

FIG. 1.

Whole-blood mefloquine concentrations during follow-up in each of the treatment groups. Data points represent the median values, and error bars extend to the 10th and 90th percentiles. (A) Group A, mefloquine (25 mg/kg on day 2) with food; (B) group B, mefloquine (15 mg/kg on day 2 and 10 mg/kg on day 3) with food; (C) group C, mefloquine (25 mg/kg on day 0) with food; (D) group D, mefloquine (25 mg/kg on day 2) without food.

The median (range) time that the concentration was >500 ng/ml (the approximate in vivo MIC of mefloquine for resistant P. falciparum) was 20 (0 to 26) days; in one patient, a 12 year old girl in group C, concentrations of mefloquine in blood never rose above 500 ng/ml; the peak Cmax was 422 ng/ml. The median (range) AUC for concentrations of >500 ng/ml was 7,159 (0 to 39,693) ng/ml · day, accounting for 28% (0 to 63%) of the total AUC. In total, 78% (95% CI, 76 to 79%) of the AUC occurred after the 5th day following first administration of mefloquine, and 55% (95% CI, 52 to 57) of the AUC occurred after the 12th day. The AUC (total and that for >500 ng/ml) and time that the concentration was >500 ng/ml were all correlated significantly with single time point mefloquine levels taken on any day. This correlation was greatest for the last sample taken (26th day for groups A, B, and D and 28th day for group C), with rS values of 0.93 for the total AUC, 0.71 for the AUC for concentrations of >500 ng/ml, and 0.87 for the time that the concentration was >500 ng/ml (P < 0.001 for each). In the paired analysis of derived pharmacokinetic parameters there was no significant difference in any of the parameters between the two groups in which mefloquine was administered with food (group A [single dose] versus group B [split dose]). In the two groups in which mefloquine was given as a single dose, Cmax values were significantly higher in group D (without food) than in group A (with food) (median [range], 1,935 [809 to 4,137] ng/ml and 1,606 [710 to 2,881] ng/ml, respectively; P = 0.04), although there was no difference in any of the other pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. Comparing the two groups in which mefloquine was given without food (group C [day 0] and group D [day 2]), group C had a significantly lower AUC (median [range], 20,181 [6,441 to 52,491] ng/ml · day and 28,196 [19,133 to 73,716] ng/ml · day, respectively; P = 0.003) and higher CL/f (median [range], 1.24 [0.48 to 3.88] liters/kg/day and 0.89 [0.34 to 1.31] liters/kg/day, respectively; P = 0.001). Patients in group C also had a lower AUC after the fifth day following the first administration of mefloquine (an estimate of the postabsorption AUC) (median [range], 15,250 (6,387 to 45,965) ng/ml · day and 27,318 [13,672 to 66,116] ng/ml · day, respectively; P = 0.005). The AUC for concentrations of >500 ng/ml was also less in group C (median [range], 5,303 [41 to 23,742] ng/ml · day and 7,638 [4,540 to 39,693] ng/ml · day, respectively; P = 0.015), with patients in group D having mefloquine levels of >500 ng/ml for a median of 8 days longer than those in group C (range, −8 to 18 days; P = 0.002). Assuming that there was no difference in clearance between the groups, delaying the administration of mefloquine until day 2 (48 h after the first dose of artesunate) increased its oral bioavailability (f) by a mean of 1.72-fold (95% CI, 1.36- to 2.09-fold). Mefloquine samples in group B were taken 24 h after patients received their first dose of mefloquine (15 mg/kg) but not after their second dose (10 mg/kg). The derived pharmacokinetic parameters may therefore have underestimated the actual Cmax and AUC. The median mefloquine level in group A, 24 h after receiving the 25-mg/kg dose, was 1,614 (range, 704 to 2,881) ng/ml, significantly greater than that in group B, who had received only 15 mg/kg (1,147 [range, 838 to 2,386] ng/ml; P = 0.01). By the fifth day after the first dose of mefloquine had been given to both groups, those patients receiving the split dose had significantly higher mefloquine levels (median, 1,284 [range, 853 to 2,014] ng/ml versus 1,059 [range, 488 to 2158] ng/ml; P = 0.03), but this difference was no longer apparent on or after the seventh day. There was no difference between groups A and B with regard to the time that the concentration was >500 ng/ml, the AUC for concentrations of >500 ng/ml, or the AUC after the fifth day following mefloquine administration (an estimate of the postabsorption AUC).

DISCUSSION

Mefloquine has proved to be a simple and highly effective treatment for adults and children with falciparum malaria infections resistant to both chloroquine and pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine (17). Therapeutic efficacy is dependent upon adequate drug absorption and maintenance of parasiticidal blood levels (levels above the MIC), until all parasites have been eliminated from the body. Since 1994 the standard treatment of choice for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in the displaced persons on the western border of Thailand has been a combination regimen of high-dose mefloquine (25 mg/kg) plus 3 days of artesunate (4 mg/kg/day) (11). The artesunate component acts rapidly, reducing the infecting biomass by a factor of approximately 10−8 (21). Although artesunate is eliminated quickly from the body, after a 3-day course relatively few parasites (maximum, 106) remain for mefloquine to remove. The long t1/2 of mefloquine ensures that high concentrations in blood are present at this time, and provided that these remain above the MIC until all parasites have been eliminated, cure will result (22). Previous studies on the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine have been carried out on relatively small numbers of subjects, most of whom were healthy adult volunteers. Following a single oral dose, peak levels are usually reached within 8 to 24 h, and in malaria infections with drug-sensitive parasites, therapeutic levels are maintained for considerably more than 7 days (6). Studies in healthy volunteers have shown good oral bioavailability which is augmented significantly by food; however, absorption in patients with acute malaria has been found to be erratic, and there is some evidence that it is dose limited (18).

The present study of mefloquine pharmacokinetics represents the largest series to date of patients acutely infected with P. falciparum. The pharmacokinetic parameters estimated in this study are generally similar to those previously reported in adults (6) and in children (10, 15), although whole-blood concentrations were lower and thus estimates of apparent V/f were slightly higher. Estimates of t1/2 were similar in the four large groups studied. The distribution of values in this large series was log normal, with an overall geometric mean t1/2 of 13 days. Thus, 10% of children would be expected to show t1/2 values of >20.5 days, and 10% would be expected to show t1/2 values of <8.4 days. This estimate is similar to that in adults (6). The mean t1/2 of mefloquine in younger children (<2 years) (15) is slightly shorter than that in the older children studied here and in adults with acute malaria (11 versus 13 days, respectively), although there is considerable interindividual variance.

In this large and carefully matched series it is unlikely that there were significant differences in true V/f or clearance capacity between the patient groups. Assuming no capacity limitation in clearance, the apparent differences in pharmacokinetic parameters resulted therefore from differences in oral bioavailability. The present study shows that although delaying the administration of mefloquine until the third day after admission (day 2) rather than giving it on admission (day 0) did not increase the peak mefloquine levels obtained, it did increase the overall bioavailability by 72% (minimum, 1.4-fold), and this resulted, on average, in an additional 8 days of therapeutic blood mefloquine levels. Delaying the administration of mefloquine until day 2 in the combination regimen (i.e., once the patient is aparasitemic and afebrile), has also been shown to reduce the risk of vomiting by a third (14). The in vivo consequences of this are apparent in patients presenting with high parasite counts (>40,000 μl−1). These patients are three times less likely to recrudesce during follow-up when mefloquine is given during recovery (14). The considerable interindividual variation in mefloquine absorption, distribution, and elimination has important therapeutic consequences, as inadequate concentrations in blood lead to treatment failure and provide a powerful selective pressure for the development of resistance (22). Peak concentrations varied between four- and sevenfold in this series. The high dose of mefloquine currently used is required to reduce the number of patients with inadequate drug levels, but this is costly and risks toxicity in those with the higher drug concentrations. If bioavailability could be improved, then variability might be reduced. Administration of mefloquine in convalescence improved bioavailability, presumably because by this time patients were generally afebrile and eating normally, and their gastrointestinal functions had returned to normal, but it did not reduce interindividual variability. This suggests that even with delayed administration bioavailability is still far from complete.

A single dose of mefloquine (25 mg/kg) is easy to administer and convenient, but early vomiting of the drug is a common problem, occurring in up to 8% of patients. The risk has been shown to be greatest in children less than 5 years old and febrile patients and following the administration of a high dose of mefloquine (25 mg/kg) compared with a lower dose (15 mg/kg) (20). Previous pharmacokinetic studies with mefloquine monotherapy have shown that a split-dose regimen might result in higher bioavailability (19). In the present study there was no significant difference between patients receiving split and single dosing, when mefloquine was administered during recovery, but our sampling may have failed to capture the peak levels after the administration of the split-dose regimen and for this reason may have underestimated the Cmax and bioavailability with this regimen. When comparing mefloquine levels 72 h after starting mefloquine treatment, there was a 21% increase for patients receiving the split dose compared to those receiving the single dose. However, this difference was no longer apparent after 120 h and therefore did not increase the time that mefloquine levels were above the MIC for P. falciparum. These data suggest that the higher apparent bioavailability observed in our previous study with split dosing may have resulted from the delay in administering the second part of the dose. Acute malaria is associated with reduced absorption of oral mefloquine. Vomiting is also more likely if mefloquine is administered in the acute phase. Readministration of mefloquine after vomiting does not necessarily ensure adequate subsequent drug levels (19). In the present study, any patient vomiting the mefloquine medication was excluded. Since lower doses of mefloquine are better tolerated, if compliance can be achieved, a split-dose regimen would result in therapeutic blood concentrations being reached more reliably.

Overall, these results suggest that, when given in combination with artesunate, mefloquine should be administered during recovery. Splitting the dose into 15- and 10-mg/kg doses at least 8 h apart decreases the rate of vomiting of mefloquine, and this may further ensure that adequate levels of mefloquine are reached more reliably. The addition of a fatty meal does not appear to be warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Karen staff of the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit for support and technical assistance. We thank Feiko ter Kuile for his help in setting up this study.

Mefloquine assays were supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command. This study was part of the Wellcome-Mahidol University Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Programme, supported by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crevoisier C, Barre J. 13th International Congress for Tropical Medicine and Malaria. Pattaya, Thailand. 1992. Food increases the bioavailability of mefloquine; p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crevoisier C, Handschin J, Barre J, Roumenov D, Kleinbloesem C. Food increases the bioavailability of mefloquine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:135–139. doi: 10.1007/s002280050351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edstein M D, Lika I D, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabcharoen A, Webster H K. Quantitation of fansimef components (mefloquine + sulfadoxine + pyrimethamine) in human plasma by two high performance liquid chromatographic methods. Ther Drug Monit. 1991;13:146–151. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franssen G, Rouveix B, Lebras J, Bauchet J, Verdier F, Michon C, Ricaire F. Divided-dose kinetics of mefloquine in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karbwang J, Na-Banchang K, Thanavibul A, Back D J, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine alone or in combination with artesunate. Bull W H O. 1994;72:83–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karbwang J, White N J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;19:264–279. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199019040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Looareesuwan S, Viravan C, Vanijanonta S, Wilairatana P, Suntharasamai P, Charoenlarp P, Arnold K, Kyle D, Canfield C, Webster H K. A randomised trial of mefloquine, artesunate, and artesunate followed by mefloquine in acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1992;339:821–824. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luxemburger C, Thew K L, Webster H K, White N J, Kyle D E, Maelankirri L, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Nosten F. The epidemiology of malaria in a Karen population on the western border of Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Na Bangchang K, Karbwang J, Banmairuroi V, Bunnag D, Harinasuta T. Mefloquine monitoring in acute uncomplicated malaria treated with Fansimef and Lariam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1993;24:221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Na Bangchang K, Karbwang J, White N J. Mefloquine pharmacokinetics and resistance in children with acute falciparum malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:556–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nosten F, Luxemburger C, ter Kuile F O, Woodrow C, Eh J P, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Treatment of multi-drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria with 3-day artesunate-mefloquine combination. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:971–977. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price R N, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Kham A, Brockman A, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Artesunate versus artemether in combination with mefloquine for the treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:523–527. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price R N, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, ter Kuile F O, Paiphun L, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Effects of artemisinin derivatives on malaria transmissibility. Lancet. 1996;347:1654–1658. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price R N, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, van Vugt M, Phaipun L, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Artesunate/mefloquine treatment of multi-drug resistant falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:574–577. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singhasivanon V, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabcharoen A, Attanath P, Webster H K, Wernsdorfer W H, Sheth U K, Lika I D. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in children aged 6 to 24 months. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1992;17:275–279. doi: 10.1007/BF03190160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ter Kuile F, Luxemburger C, Nosten F, Phaipun L, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Predictors of mefloquine treatment failure: a prospective study in 1590 patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:660–664. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ter Kuile F O, Nosten F, Thieren M, Luxemburger C, Edstein M D, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Phaipun L, Webster H K, White N J. High dose mefloquine in the treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1393–1400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ter Kuile F O. Mefloquine, halofantrine and artesunate in the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in a multidrug resistant area. Doctoral thesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: University of Amsterdam; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.ter Kuile F O, Teja-Isavatharm P, Edstein M D, Keeratithakul D, Dolan G, Nosten F, Phaipun L, Webster H K, White N J. Comparison of capillary whole blood, venous whole blood, and plasma concentrations of mefloquine, halofantrine, and desbutyl-halofantrine measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:778–784. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ter Kuile F O, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Kyle D, Teja-Isavatharm P, Phaipun L, Price R N, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White N J. Mefloquine treatment of acute falciparum malaria: a prospective study of non-serious adverse effects in 3673 patients. Bull W H O. 1995;73:631–642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White N J. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1413–1422. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White N J. Preventing antimalarial drug resistance through combinations. Drug Resist Updates. 1998;1:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(98)80208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. 1990. Control of tropical diseases. Severe and complicated malaria. Trans R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 84(Suppl. 2):1–65. [PubMed]