Abstract

Where do our political attitudes originate? Although early research attributed the formation of such beliefs to parent and peer socialization, genetically sensitive designs later clarified the substantial role of genes in the development of sociopolitical attitudes. However, it has remained unclear whether parental influence on offspring attitudes persists beyond adolescence. In a unique sample of 394 adoptive and biological families with offspring more than 30 years old, biometric modeling revealed significant evidence for genetic and nongenetic transmission from both parents for the majority of seven political-attitude phenotypes. We found the largest genetic effects for religiousness and social liberalism, whereas the largest influence of parental environment was seen for political orientation and egalitarianism. Together, these findings indicate that genes, environment, and the gene–environment correlation all contribute significantly to sociopolitical attitudes held in adulthood, and the etiology and development of those attitudes may be more important than ever in today’s rapidly changing sociopolitical landscape.

Keywords: political attitudes, adoption, behavioral genetics, environment, open data, open materials, preregistered

A wide range of social agents and institutions, including peers, teachers, schools, and popular media, have been hypothesized as contributing to the development of our social and political attitudes (Barrett, 2007). Foremost among these are parents, who are seen to play a primary role in the political socialization of their children. Children spend their formative years with their parents, who might shape ideological beliefs either directly (e.g., through political discussion) or indirectly (e.g., through modeling). The importance of parents was implicated in early research by the eminent psychologist Gordon Allport, who concluded that the ethnic biases of young children mirrored those of their parents (Allport, 1954), and his Harvard contemporary, the prominent developmental psychologist Eleanor Maccoby, who showed that political-party affiliation and candidate endorsements of first-time voters closely paralleled those of their parents (Maccoby et al., 1954). The association of parental sociopolitical attitudes with those of their children has been established in more than 100 subsequent empirical reports over the past 60 years (Degner & Dalege, 2013).

Given the consistency with which parent–offspring resemblance has been observed, it may seem surprising that some researchers have questioned the role that parents play in attitude formation. Perhaps the greatest challenge to the primacy afforded parental socialization comes from behavioral-genetics research, which has shown that political and social attitudes are heritable (Alford et al., 2005). The existence of genetic influences on attitude formation raises the possibility that parent–offspring resemblance is due to the genes they share rather than their common environment.

Studies from the 1970s and 1980s comparing identical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins found that twin similarity on sociopolitical attitudes and opinions, such as radicalism versus conservatism (Eaves & Eysenck, 1974) and endorsement of the death penalty, evolutionary theory, and abortion (N. G. Martin et al., 1986), could be attributed almost entirely to heritable effects. Environmental influences were also relevant, although they appeared to be limited primarily to factors that contributed to twins’ attitudinal differences rather than similarities, which argues against the importance of parents. This pattern of findings has been replicated in more recent and larger twin studies. Research based on the Swedish Twin Registry (Oskarsson et al., 2015) and the Minnesota Twin Registry (Funk et al., 2013), for example, has found that individual differences in social and political attitudes, including egalitarianism, right-wing authoritarianism, and support for immigration and redistribution, are principally due to genetic factors and environmental factors not shared by twins who were reared together. Aspects of the twins’ environments that they shared (what twin researchers call the shared environment) were found to have negligible effects on social and political attitudes. This conclusion gained further support from a Minnesota study that found that twins reared apart were almost exactly as similar in right-wing authoritarian attitudes as twins reared together (McCourt et al., 1999). The consistent finding of little shared environmental influence in twin studies of political and social attitudes suggests that parents might have a limited effect on attitude formation.

The failure to find evidence of parental influences with the classic twin-study design (i.e., comparison of monozygotic and dizygotic twins who were reared together) may be a result of the limitations of this research design rather than an indication that parents do not politically socialize their children (Beckwith & Morris, 2008). To address this question, several investigators have extended the classical twin study by including the parents and other relatives of twins in what is called a twin-family design. Yet large twin-family studies have either concluded that parents have limited impact on the social and political attitudes underlying their children’s political orientation (Hufer et al., 2020; Kandler et al., 2012) and political beliefs (Hatemi et al., 2010) or failed to find consistent evidence of parent-to-offspring transmission for attitudes such as conservatism and support for taxation (Eaves et al., 1999).

Statement of Relevance.

Understanding the origin and development of political attitudes has become increasingly important to the general public in our modern sociopolitical milieu. Although this question has been empirically investigated for decades by social, political, and behavioral-genetics psychologists, it has remained unclear to what extent both genetics and the home environment fostered by the parents can influence the development of these beliefs beyond adolescence. Using a unique sample of nearly 400 adult adoptive and biological families, we analyzed genetic and environmental sources of variance for seven political-attitude scales, including authoritarianism, egalitarianism, and social and economic liberalism. We found strong correlations between parent and offspring attitudes in both family types, indicating that parental socialization and gene–environment correlation persist well into adulthood even in the presence of substantial genetic contribution. In sum, these findings contribute novel insight to the origin and development of such attitudes in our increasingly complex sociopolitical world.

The difficulty in trying to infer parent effects from twin or even twin-family designs is that the inference is necessarily indirect, occurring when observed twin similarity cannot be accounted for entirely by genetic factors. Adoption studies provide a direct way of assessing parental environmental influences, because in the absence of selective placement, resemblance between parents and adopted offspring can be due only to environmental mechanisms (McGue et al., 2007). The few adoption studies that exist contrast with twin studies in providing tantalizing hints at the potential influence of the shared family environment. In a study of adopted and biological adolescents between 12 and 15 years old, Abrahamson et al. (2002) reported significant shared environmental and parent–offspring cultural-transmission effects for the Wilson-Patterson scale of political conservatism as well as a measure of religiousness. The latter finding was replicated in a subsequent study of adopted adolescents (Koenig et al., 2009). Perhaps most intriguing, Oskarsson et al. (2018) demonstrated a substantial effect of maternal socialization on political candidacy in a large sample of adult Swedish adoptees.

An additional factor that complicates interpretation of existing research on parent contributions to social attitudes is the age range represented in the offspring samples. In the United States, at least, it has remained uncertain to what extent parents can influence their offspring’s political attitudes up to and subsequent to the age at which they can meaningfully participate in politics, such as in voting. Nonetheless, studies of parent–offspring attitude similarity are overwhelmingly based on samples of offspring in childhood or adolescence (Degner & Dalege, 2013), as were the two previously mentioned adoption studies that reported evidence for parent–offspring transmission. Significantly, parental influences on attitude formation may wane as offspring leave their rearing homes and are exposed to a wide range of social factors. A consistent finding from the behavioral-genetics literature for a broad range of phenotypes is that shared environmental influences, when they exist, are primarily limited to childhood or adolescence and do not endure into adulthood (Bergen et al., 2007). This may also be the case with social and political attitudes. A large cross-sectional twin study found evidence for strong shared environmental influences on political conservatism up through age 20, which, however, dissipated at later ages (Eaves et al., 1997). Similarly, an adoption study of offspring in early adulthood failed to find evidence of shared environmental effects or parent-to-offspring cultural transmission for a measure of authoritarianism (Scarr, 1981).

Here we report evidence for parent-to-offspring cultural transmission for seven validated scales of social and political beliefs in a Minnesota sample of adoptive and biological families. These findings are the first exploration of the environmental and genetic contributions to a variety of social and political attitudes in a large, fully adult adoptive sample of American families.

Method

Sample

Participating families were originally recruited and assessed through the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) between 1998 and 2004 (McGue et al., 2007). A representative sample of adoptive and biological families were identified from records of large adoption agencies and state birth records. Study eligibility was limited to families composed of at least one parent and two adolescent offspring within 5 years of one another in age (mean age of offspring at first assessment = 14.9 years, SD = 1.6) and to families living within driving distance of the Twin Cities research lab. Additionally, adopted adolescent offspring were required to have been placed for adoption prior to turning 2 years old (M = 4.7 months, SD = 3.4 months). After parents were interviewed to establish eligibility, a majority of families agreed to participate (63% of the adoptive families and 57% of the biological families).

The current follow-up assessment began in 2017 and is being conducted via phone interview, mailed survey, or online survey with every eligible parent and sibling pair. As of June 2020, at least one member of a total of 394 families has participated in the current assessment for the scales presented in this study. This includes a total of 287 mothers, 205 fathers, 370 adopted offspring, and 310 biological offspring; offspring now average 31.8 years of age (Table 1). Comparison of current participants with nonparticipants on intake measures revealed no substantial attrition effects (see Table S6 in the Supplemental Material).

Table 1.

Description of the Sample

| Group | n | Mean age at intake (SD) |

Mean age at third follow-up (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | |||

| Mothers | 287 | 46.6 (4.2) | 63.9 (4.8) |

| Fathers | 205 | 48.2 (4.4) | 65.4 (4.7) |

| Adopted offspring | |||

| Female | 237 | 15.0 (2.1) | 32.6 (2.9) |

| Male | 133 | 14.9 (1.7) | 31.7 (2.5) |

| Biological offspring | |||

| Female | 189 | 14.9 (2.0) | 31.6 (2.5) |

| Male | 121 | 14.9 (1.8) | 31.1 (2.6) |

Note: The sample for the current study was a subset of the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study. The table includes only participants with valid scores for political ideology. Valid sample size for other phenotypes analyzed are within ±3 of this reported sample size. Ages are given in years.

Sociopolitical-attitude scales

Seven sociopolitical-attitude scales were administered to both parents and offspring during their third follow-up assessment. These addressed political orientation, authoritarianism, egalitarianism, retribution, religiousness, social liberalism, and economic liberalism.

Political orientation was assessed with a single item on a scale from 1 to 5 (higher scores indicate more liberal views). Authoritarianism was assessed using 12 items measuring three facets (four items for each) of authoritarianism (authoritarian subordination, authoritarian aggression, and authoritarian conventionalism) from Duckitt et al.’s (2010) tripartite authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model. Egalitarianism was assessed using six items from the study by Feldman and Steenbergen (2001) and an additional two items from the study by Feldman (1988). Retribution was measured with four items from the study by Sidanius et al. (2006) and a single retribution item from the World Values Survey used by N. D. Martin et al. (2017). Religiousness was assessed with nine items used in previous SIBS research (Koenig et al., 2009). Seventeen items were adapted from General Social Survey items, 11 measuring social liberalism and six measuring economic liberalism (Smith et al., 2018; Weeden & Kurzban, 2016). Indices of reliability and example items for each scale are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability Comparisons and Example Items for Each Political-Attitude Scale and the ICAR-16

| Scale | α | ω h | ω t | Number of items | Example item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarianism | .86 | .74 | .88 | 12 | Obedience and respect for authority are the most important virtues children should learn. |

| Egalitarianism | .87 | .79 | .90 | 8 | If wealth were more equal in this country, we would have many fewer problems. |

| Social liberalism | .86 | .72 | .89 | 11 | The use of marijuana should be legal. |

| Economic liberalism | .84 | .77 | .90 | 6 | The government is spending too little money on Social Security. |

| Retribution | .72 | .64 | .80 | 5 | Those who hurt others deserve to be hurt themselves. |

| Religiousness | .89 | .89 | .92 | 9 | How often do you attend religious services? |

| ICAR-16 | .80 | .64 | .82 | 16 | If the day after tomorrow is two days before Thursday, then what day is today? |

Note: Political orientation is not included here because it was based on a single item (“What is your political orientation?”) rated on a 5-point scale (1 = extremely conservative, 5 = extremely liberal). Reliability scores are given for Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω hierarchical (ω h ), and McDonald’s ω total (ω t ) and were computed with the omega function of the psych package for R (Version 2.1.3; Revelle, 2017). ICAR-16 = 16-item short form of the International Cognitive Ability Resource.

Given the high intercorrelation among attitude scales (see Tables S8–S10 in the Supplemental Material), we computed a composite score for each individual by averaging standard scores within offspring and each parent and reversing the scales with opposite poles. A common-sense interpretation of this composite is that higher values represent liberal attitudes, and lower values conservative attitudes, broadly construed. (Detailed item content for all scales and each item’s correlation with the composite in the full sample can be found in Tables S1–S5 in the Supplemental Material, and descriptive statistics for mothers, fathers, and offspring are shown for both family types in Table S7 in the Supplemental Material.)

Other variables

We used a 16-item short form of the International Cognitive Ability Resource (ICAR-16), a measure of general intelligence, to assess this dimension in offspring and both parents. The ICAR-16 is a public-domain cognitive-assessment tool created by Condon and Revelle (2014). General intelligence is well known to be highly heritable and robust against cultural transmission, particularly in adulthood (Plomin et al., 2016; Polderman et al., 2015; Scarr & Weinberg, 1978). This measure is therefore useful as a negative control to evaluate whether nongenetic parental influence on political attitudes is likely to be a sampling artifact. A negative control is a condition or analysis with no expected effect; if there is indeed no effect, this can improve confidence that any positive results elsewhere are nonartifactual. Reliability and other details of the ICAR-16 can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Age, years of education, and highest degree achieved were also included in correlation tables for both family types (see the Supplemental Material), along with family socioeconomic status (SES), which was computed as the mean of both parents’ (where available) standardized composite of Hollingshead job status, years of education, and income (sample α = .704).

Biometric modeling

For each phenotype, genetic influence (heritability) was calculated with the formula ; the sum of maternal and paternal environment was calculated using ; and the sum of maternal and paternal gene–environment covariance was equivalent to The copath µ refers to the phenotypic correlation between parents, which is modeled via special rules originally described by van Eerdewegh (1982). Details of parameter estimates and variance components, along with model assumptions and justifications, can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Results

All observed phenotypes showed a general pattern: Adoptive relatives resembled each other in political beliefs, and biological relatives resembled each other even more. On its own, this pattern suggests that political beliefs are both heritable and influenced by family environment. Given the evidence that adopted children were placed in their homes through a quasirandom process in the present sample (see the Supplemental Material; McGue et al., 2007; Willoughby et al., 2021), a significant correlation between a parent and offspring trait in adoptive families likely reflects a causal effect of the former (or something highly correlated) on the latter.

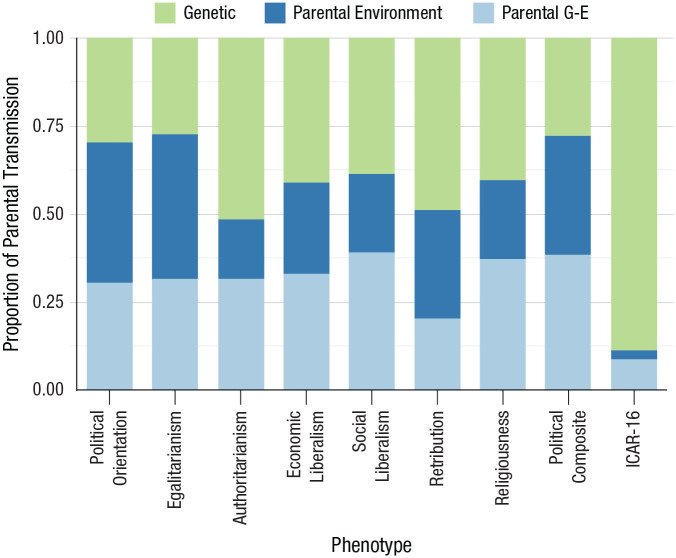

Parent–offspring correlations

Parent–offspring correlations were significant and moderately sized across most political attitudes for both biological and adoptive families and were generally similar for mothers and fathers. Sibling correlations were of smaller magnitude than parent–offspring correlations for all attitude scales. In both family types, the strongest parent–offspring relationships for individual phenotypes were found for social liberalism, religiousness, and egalitarianism, and the weakest were found for retribution. Parent and offspring composite scores were found to be more similar between parents and offspring of both family types than any individual scale scores were (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots showing correlations between parent and offspring political-attitude composite scores as a function of parent gender, separately for biological and adoptive families. Solid lines indicate best-fitting regressions; error bands indicate 95% confidence intervals.

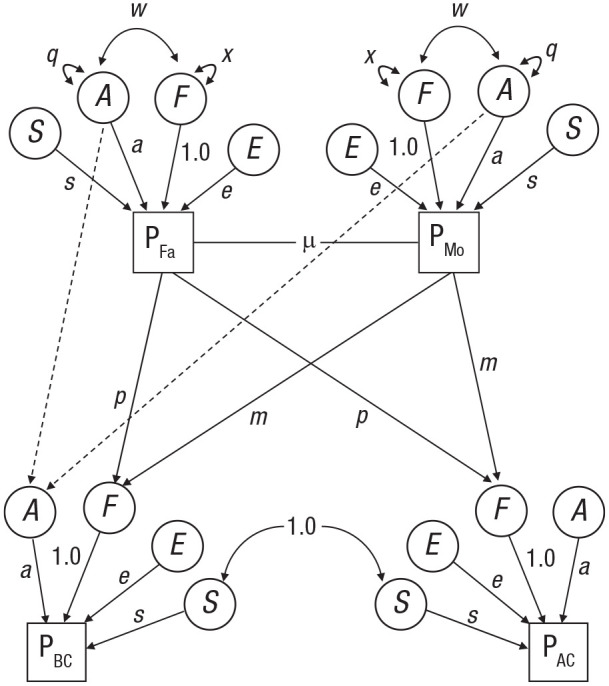

To model expected correlations for each pair of relationships, we adapted familial-relationship equations from Keller et al. (2009) to include adoptive parent and sibling relationships (Fig. 2). The model allowed for parent-to-offspring transmission through both genetic (biological offspring only) and environmental (both offspring types) pathways. The model also allowed for assortative mating, sibling environmental effects, and gene–environment correlation. Observed and model-predicted correlations for each relationship pair are shown in Table 3 (95% confidence intervals [CIs] for observed correlations are shown in Table S14 in the Supplemental Material). We evaluated model fit for each scale with the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) and the goodness-of-fit index (GFI). The SRMR is a summary of the magnitude of difference between observed and predicted correlations; a good fit is generally considered to be less than .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The GFI is computed as the proportion of variance accounted for by the estimated population covariance; a GFI of .95 or above is generally considered good fit, and a GFI between .90 and .95 is generally considered acceptable fit (McDonald, 1999). Model fit was similarly strong for all measured scales (mean SRMR = .04; mean GFI = .97).

Fig. 2.

Path diagram illustrating variance components and effects in an example family consisting of two parents and one adopted and one biological child. Only those components estimated in our analyses are shown. Boxes indicate observed (measured) phenotypes for the father (PFa), mother (PMo), biological child (PBC), and adopted child (PAC), and circles indicate the latent (unmeasured) variables: additive genetic (A), parental environment effect (F), sibling environment effect (S), and nonshared environmental effect (E). Paths are shown for direct paternal transmission (p), direct maternal transmission (m), and the effect of the genetic score on the phenotype (a), and the copath is shown for assortative mating (µ). Values on paths with solid single-headed arrows are as labeled; the dashed paths from parent genotype to biological-child genotype (A) were fixed to 1/2 according to standard genetic theory. Values on double-headed arrows are either correlations (w = gene–environment covariance) or variance when traced back on itself (x = variance of the family environment, equivalent to m2 + p2 + 2mpm; q = variance of additive genetic effects).

Table 3.

Observed and Model-Predicted Correlations and Model Fit for Each Political-Attitude Phenotype, the Political-Attitude Composite, and the ICAR-16 Score

| Variable | Parent–offspring correlations | Sibling correlations | m | Fit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother–biological | Father–biological | Mother–adoptive | Father–adoptive | Biological–biological | Adoptive–biological | Adoptive–adoptive | Father–mother | SRMR a | GFI b | |

| Political orientation | .06 | .97 | ||||||||

| Observed | .41 | .48 | .39 | .36 | .43 | .12 | .14 | .69 | ||

| Expected | .46 | .48 | .35 | .37 | .33 | .23 | .19 | .69 | ||

| Egalitarianism | .05 | .97 | ||||||||

| Observed | .48 | .57 | .40 | .34 | .33 | .20 | .26 | .68 | ||

| Expected | .50 | .51 | .39 | .39 | .37 | .26 | .21 | .68 | ||

| Authoritarianism | .05 | .97 | ||||||||

| Observed | .44 | .49 | .30 | .22 | .34 | .02 | .04 | .59 | ||

| Expected | .46 | .45 | .26 | .24 | .33 | .14 | .08 | .60 | ||

| Economic liberalism | .02 | .98 | ||||||||

| Observed | .49 | .47 | .32 | .30 | .30 | .12 | .11 | .65 | ||

| Expected | .48 | .46 | .32 | .30 | .33 | .18 | .12 | .65 | ||

| Social liberalism | .04 | .99 | ||||||||

| Observed | .65 | .65 | .37 | .37 | .48 | .22 | .26 | .70 | ||

| Expected | .63 | .63 | .38 | .38 | .53 | .29 | .19 | .70 | ||

| Retribution | .05 | .94 | ||||||||

| Observed | .26 | .26 | .14 | .20 | ~0 | .08 | ~0 | .30 | ||

| Expected | .22 | .24 | .16 | .18 | .11 | .06 | .05 | .30 | ||

| Religiousness | .03 | .97 | ||||||||

| Observed | .56 | .61 | .35 | .36 | .53 | .22 | .21 | .70 | ||

| Expected | .57 | .60 | .33 | .37 | .51 | .30 | .21 | .70 | ||

| Political-attitude composite | .04 | .98 | ||||||||

| Observed | .65 | .65 | .47 | .46 | .46 | .24 | .21 | .82 | ||

| Expected | .64 | .64 | .46 | .46 | .49 | .32 | .23 | .82 | ||

| ICAR-16 | .02 | .99 | ||||||||

| Observed | .27 | .31 | −.03 | .10 | .27 | .05 | .07 | .19 | ||

| Expected | .24 | .33 | −.01 | .08 | .30 | .06 | .05 | .19 | ||

Note: Expected correlations were predicted from a biometric model after fitting. For 95% confidence intervals for observed correlations, see Table S14 in the Supplemental Material. ICAR-16 = 16-item short form of the International Cognitive Ability Resource.

For the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), a value less than .08 is generally considered good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). bFor the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), a value of .95 or greater is generally considered good fit, and a value between .90 and .95 is generally considered acceptable fit (McDonald, 1999).

Familial correlations for scores on the ICAR-16, our short-form measure of general intelligence (Condon & Revelle, 2014), were included as a conceptual control to evaluate whether parent–offspring correlations were likely to be a sampling artifact. These correlations were of moderate size and significant only for biological relationships in our sample, consistent with findings that parent–offspring correlations for IQ in adoptive families decline over time (Scarr & Weinberg, 1978). We additionally investigated whether family SES, geographic distance between parents’ homes and their adult offspring, and political composition of the county in which the offspring were reared acted as significant confounders or mediators of parent–offspring resemblance for all phenotypes. For example, if statistically controlling SES reduced the magnitude of parent–offspring resemblance, this would suggest that SES (or something highly correlated with it) affects both parent and offspring traits. We tested this hypothesis by including these three characteristics as covariates in regression models, along with parent phenotype for all traits in predicting offspring phenotypes. In these models, a significant role of the covariate in parent–offspring resemblance would be evident if the slope for the effect of the offspring phenotype on the parent phenotype decreased. These analyses produced no compelling evidence of attenuating parent–offspring resemblance in either family type (see Table S15 and the supporting text in the Supplemental Material).

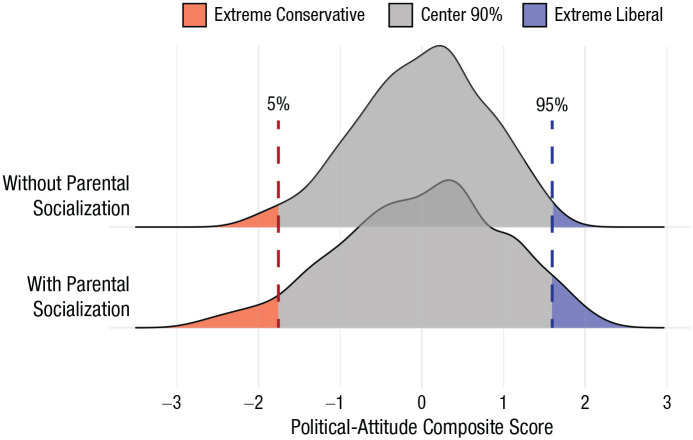

Variance decomposition

Variance decomposition for each political-attitude scale revealed substantial parental contributions of both genetics and the shared environment to the political attitudes of their offspring. The relative contributions of genes and shared environment conferred by the parents can be seen in Figure 3. Although maternal and paternal effects were modeled separately, their contributions did not differ significantly for any offspring outcome phenotype. Relative to genetic effects, the strongest parental-socialization effects were seen for political orientation, the political-attitude composite, and egalitarianism. The short-form measure of general intelligence, for which genetic effects contribute the lion’s share of parent–offspring resemblance, again provides a useful demonstration that parental-socialization effects for political phenotypes are unlikely to be an artifact of the sample. Variance-component estimates for each phenotype are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of variance in parent–offspring transmission attributable to parent genetics, parental environment, and parental gene–environment (G-E) covariance for each of the seven political-attitude scales, their composite score, and the 16-item short form of the International Cognitive Ability Resource (ICAR-16; included as a negative control).

Table 4.

Decomposition of Variance for Each of the Seven Political-Attitude Phenotypes, the Political-Attitude Composite, and the ICAR-16 Score

| Variable | Genetic

(A): heritability (h2) |

Shared environment (C) | Nonshared environment (E) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental environment |

Sibling environment |

Gene–environment covariance |

|||

| Political orientation | .10 [.01, .20] | .14 [.09, .20] | .03 [.00, .11] | .10 [.01, .17] | .63 [.57, .69] |

| Egalitarianism | .11 [.00, .21] | .16 [.10, .24] | .03 [.00, .11] | .12 [.00, .19] | .59 [.52, .66] |

| Authoritarianism | .21 [.10, .32] | .07 [.04, .11] | .00 [.00, .04] | .13 [.07, .17] | .59 [.53, .65] |

| Economic liberalism | .16 [.05, .27] | .10 [.06, .16] | .00 [.00, .06] | .13 [.05, .18] | .61 [.55, .67] |

| Social liberalism | .23 [.15, .31] | .13 [.09, .18] | .01 [.00, .08] | .23 [.17, .27] | .40 [.33, .47] |

| Retribution | .07 [.00, .22] | .05 [.02, .08] | .00 [.00, .02] | .03 [.00, .07] | .85 [.80, .89] |

| Religiousness | .22 [.11, .33] | .12 [.07, .17] | .05 [.00, .13] | .20 [.13, .25] | .41 [.34, .49] |

| Political-attitude composite | .15 [.07, .23] | .18 [.13, .26] | .00 [.00, .03] | .21 [.12, .26] | .46 [.40, .52] |

| ICAR-16 | .42 [.22, .62] | .01 [.00, .03] | .04 [.00, .14] | .03 [.00, .07] | .51 [.45, .58] |

Note: For each scale, we computed 95% confidence intervals (CIs; shown in brackets) over each parameter’s 200 bootstrap iterations and fixed the lower bounds of CIs at 0. Nonshared environment was computed by subtracting the heritability, parental environment, sibling environment, and gene–environment covariance from 1. For full parameter estimates, see Table S16 in the Supplemental Material. Row values add up to 1 (total phenotypic variance). Estimates with 95% CIs that do not include zero are shown in boldface. ICAR-16 = 16-item short form of the International Cognitive Ability Resource.

Strong spousal correlations were observed for all attitude scales (see Table S14 in the Supplemental Material for 95% CIs), consistent with previous research on assortative mating for social attitudes and the related Big Five personality factor of Openness (Eaves et al., 1999; Federico, in press; McCrae et al., 2008). We found spousal similarity to be most pronounced for the political-attitude composite score (r = .82), but r was well above .50 for all scales apart from retribution (r = .30).

Covariance between the latent (unmeasured) additive genetic and family-environment factors, labeled with parameter w in Figure 2, gives rise to gene–environment correlation, a phenomenon in which an individual’s genotype correlates with an environment that fosters the development of a phenotype over time (Plomin et al., 1977). In children, this often manifests passively and through the parents. For example, religious parents may transmit to their children both a genetic propensity for religiousness and access to religious experiences, such as going to church, which in turn deepen the child’s religiosity over time. Evidence for correlation between genes and the family environment in our sample is substantial, particularly for religiousness, social liberalism, egalitarianism, and the political-attitude composite. The relative contribution of gene–environment covariance to trait variance is shown in Table 4. Because this component represents the covariance shared by genes and the common family environment, it can be interpreted as contributing to the shared environmental effect; that is, the genetic correlation would not have occurred if not for the shared rearing environment of the household.

Discussion

Although the social and political sciences have begun to accept that many aspects of personality and social attitudes are influenced by our genes, the question of whether and to what extent parents are responsible for politically socializing their children has remained an open question. In a unique cohort of adult adoptive and biological families, we found evidence that the significant and persistent association between the political and social attitudes of parents and their adult offspring is explained by both the genes and the home environments that parents have conferred on their children. Variance decomposition across seven political-attitude phenotypes and a political-attitude composite reveals that this environmental effect does indeed come almost entirely from the influence of the parents rather than from an individual’s siblings and that gene–environment correlation over time contributes to the development of these traits in adulthood.

The generalizability of these findings is potentially limited for several reasons. It is unclear to what extent this pattern of effects, from a sample of chiefly Minnesotan families, would be similar in sociopolitical milieus outside of the unique political and religious climate of the modern United States. For example, many researchers have pointed out the large differences in religiosity and conservatism between the United States and other Western countries (Koenig et al., 2009), and some have even found disparate gene and environmental influences in measures of religiosity between U.S. and Australian adults (Kirk et al., 1999). Furthermore, the linkages between social and economic ideology vary substantially by country, with social conservatives in many countries endorsing economic views that in the United States are considered left wing (Malka et al., 2017). Given this, an overarching political composite may not be deeply coherent outside of the United States.

The composition of our sample is also unique. The SIBS cohort includes families with a variety of ethnicities; a majority of parents and biological children are White, and a majority of adopted offspring are Asian. Although 98% of biological offspring in this sample are White, the adopted offspring are 22% White, 68% Asian, and 10% other ethnicities. Significant differences between White and Asian adoptees were found for political orientation (Cohen’s d = 0.31) and egalitarianism (d = 0.26); Asian offspring tended toward less conservative and more egalitarian attitudes. Despite these modest ethnic differences, adopted and biological offspring did not differ at a magnitude (d) greater than 0.20 for any political-attitude phenotype. Mean differences and effects for each attitude scale and demographic criterion are shown in Tables S17 (adoption status) and S18 (ethnicity) in the Supplemental Material.

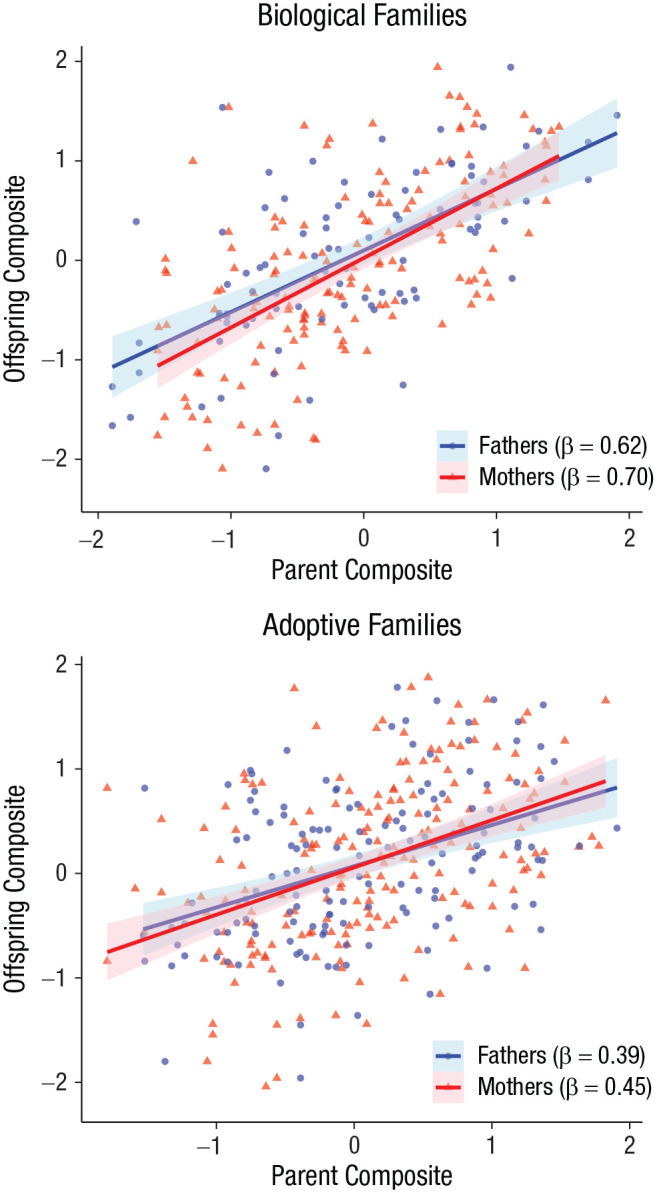

Despite these limitations, several notable implications arise from our results, particularly in the degree to which nongenetic parental transmission may increase political polarization. Parental socialization has the effect of creating more variance in the distribution of offspring political attitudes, leading necessarily to a higher frequency of attitudes at distributional tails. Given the large spousal and parent–offspring correlations observed in our sample, increased political polarization could be an important downstream consequence that would manifest in America’s changing political and cultural arena. This is consistent with previous findings that children are more likely to adopt their parents’ political attitudes in families that are more politicized (Jennings et al., 2009). We simulated a distribution of political-attitude composite scores without the nongenetic parental-transmission component, thus transforming the scores to represent a hypothetical distribution in which a larger percentage would fall within the center (Fig. 4). If the “extreme” cutoffs refer to those political-attitude composite scores that fall below 5% and above 95% in our observed sample (full model), then this would reduce the number of individuals scoring at these extremes to 2% of liberals and less than 1% of conservatives. This simulation is further explored in Table S19 and the supporting text in the Supplemental Material.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the distribution of political-attitude composite scores in the full observed model (bottom) with a hypothetical distribution lacking the component of nongenetic parental transmission (top).

Another important issue to address is that our parent–offspring correlations were generally larger than those reported previously; for example, most of the correlations on social and political items reported by Jennings et al. (2009) and Hatemi et al. (2010) fell in the range of .10 to .40, and only party identification, vote choice, school prayer, and religiosity were slightly higher (.40–.60). There are likely two reasons for this apparent discrepancy. The first concerns the reliability of the traits assessed by these previous studies, which are mostly single-item questions (with a few exceptions). The psychometric limitations of single-item scales are well known; our scales are all multi-item scales, except for political orientation, and have strong reliability (Table 2). For direct-item comparisons, single-item parent–offspring correlations for all scales can be found in Tables S20 to S24 in the Supplemental Material. These single-item parent–offspring correlations overwhelmingly fell within the range observed in previous studies.

The second likely reason for our larger correlations is the ages of offspring reported in these studies. Whereas the two offspring cohorts reported by Jennings et al. (2009) were either of high school age or in their mid-20s (assessed in the 1960s–1970s and the mid-1990s), the average age of assessment in our SIBS cohort was 32.2 years (assessed from 2017–2020). Regardless, a 2013 meta-analysis of parent–offspring similarity in social attitudes (Degner & Dalege, 2013) found that the mean parent–offspring correlation increased monotonically with offspring age, being lowest for preschool offspring and more than doubling for offspring between 18.5 and 21.5 years old (note that there were too few studies of offspring older than 22, like the participants in our sample, to be included in the meta-analysis). Importantly, when meta-analytic means were corrected for unreliability (e.g., as might occur with short scales), the age difference in average effect ranged from .18 to .53. Our results with participants in their early 30s is consistent with this latter value.

Given the novelty of this substantial parent–offspring resemblance well into adulthood, it is tempting to speculate as to the mechanisms through which parents might socialize the development of political attitudes in their children. We tested three plausible parental characteristics that could mediate or confound such transmission: SES, geographic distance between parent and offspring homes, and voting behavior in the region where the offspring were reared. Although we found no compelling evidence that these variables attenuated the observed correlations, future research that examines other plausible characteristics—such as finer-grained measurements of parenting behavior or parent–offspring contact—may be better able to look into the black box of environmental transmission in adult adoptive samples.

Although parents’ contribution to the political development of their children is clearly important, we should acknowledge the proportion of variance in these attitudes that remains unexplained. This nonshared environmental component accounts for upward of 40% of the variance in political attitudes of these now-adult children (Table 4); this represents everything from measurement error to the unique events that each of us experiences individually. Outside of the family, the environmental forces that aid the formation of political beliefs are undoubtedly complex and numerous. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that parents may correctly perceive the importance of socializing their children as they mature into adults who evaluate, navigate, and transform their political worlds. The gravity of this influence will undoubtedly play a role in shaping the future of a United States that has never been so divided in recent memory.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pss-10.1177_09567976211021844 for Parent Contributions to the Development of Political Attitudes in Adoptive and Biological Families by Emily A. Willoughby, Alexandros Giannelis, Steven Ludeke, Robert Klemmensen, Asbjørn S. Nørgaard, William G. Iacono, James J. Lee and Matt McGue in Psychological Science

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Emily A. Willoughby  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7559-1544

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7559-1544

Alexandros Giannelis  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4587-0336

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4587-0336

Steven Ludeke  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5899-893X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5899-893X

Matt McGue  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5580-1433

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5580-1433

Transparency

Action Editor: Mark Brandt

Editor: Patricia J. Bauer

Author Contributions

M. McGue designed the research concepts. W. G. Iacono played a key role in organizing samples. J. J. Lee designed analyses and code for estimating biometric parameters. S. Ludeke, R. Klemmensen, and A. S. Nørgaard played major roles in designing scale measures. E. A. Willoughby conducted the analyses, and A. Giannelis assisted with supplementary analyses. E. A. Willoughby wrote the majority of the manuscript apart from the introduction, which was primarily written by M. McGue. All the authors provided crucial edits to the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This research was funded by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation as part of the Genetics and Human Agency initiative (Grant No. 60780). Data collection for the original Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study assessment was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant Nos. MH066140 and AA011886).

Open Practices: All data and analysis code have been made publicly available via OSF and can be accessed at https://osf.io/pf97d/. The design and analysis plans for the experiments were preregistered at https://osf.io/3ba28. This article has received the badges for Open Data, Open Materials, and Preregistration. More information about the Open Practices badges can be found at http://www.psychologicalscience.org/publications/badges.

References

- Abrahamson A. C., Baker L. A., Caspi A. (2002). Rebellious teens? Genetic and environmental influences on the social attitudes of adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1392–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford J. R., Funk C. L., Hibbing J. R. (2005). Are political orientations genetically transmitted? American Political Science Review, 99(2), 1392–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Allport G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M. (2007). Children’s knowledge, beliefs and feelings about nations and national groups. Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith J., Morris C. A. (2008). Twin studies of political behavior: Untenable assumptions? Perspectives on Politics, 6(4), 785–791. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen S. E., Gardner C. O., Kendler K. S. (2007). Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 10(3), 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon D. M., Revelle W. (2014). The International Cognitive Ability Resource: Development and initial validation of a public-domain measure. Intelligence, 43(1), 52–64. 10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degner J., Dalege J. (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent-child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1270–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt J., Bizumic B., Krauss S. W., Heled E. (2010). A tripartite approach to right-wing authoritarianism: The authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model. Political Psychology, 31(5), 685–715. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L. J., Eysenck H. J. (1974). Genetics and the development of social attitudes. Nature, 249, 288–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L., Heath A., Martin N., Maes H., Neale M., Kendler K., Kirk K., Corey L. (1999). Comparing the biological and cultural inheritance of personality and social attitudes in the Virginia 30 000 study of twins and their relatives. Twin Research, 2(2), 62–80. 10.1375/twin.2.2.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L. J., Martin N., Heath A., Schieken R., Meyer J., Silberg J., Neale M., Corey L. (1997). Age changes in the causes of individual differences in conservatism. Behavior Genetics, 27(2), 121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federico C. M. (in press). The personality basis of political preferences. In Osborne D., Sibley C. G. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of political psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 416–440. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S., Steenbergen M. R. (2001). The humanitarian foundation of public support for social welfare. American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 658–677. [Google Scholar]

- Funk C. L., Smith K. B., Alford J. R., Hibbing M. V., Eaton N. R., Krueger R. F., Eaves L. J., Hibbing J. R. (2013). Genetic and environmental transmission of political orientations. Political Psychology, 34(6), 805–819. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00915.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi P. K., Hibbing J. R., Medland S. E., Keller M. C., Alford J. R., Smith K. B., Martin N. G., Eaves L. J. (2010). Not by twins alone: Using the extended family design to investigate genetic influence on political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 798–814. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hufer A., Kornadt A. E., Kandler C., Riemann R. (2020). Genetic and environmental variation in political orientation in adolescence and early adulthood: A nuclear twin family analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(4), 762–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings M. K., Stoker L., Bowers J. (2009). Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. The Journal of Politics, 71(3), 782–799. [Google Scholar]

- Kandler C., Bleidorn W., Riemann R. (2012). Left or right? Sources of political orientation: The roles of genetic factors, cultural transmission, assortative mating, and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. C., Medland S. E., Duncan L. E., Hatemi P. K., Neale M. C., Maes H. H. M., Eaves L. J. (2009). Modeling extended twin family data I: Description of the cascade model. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 12(1), 8–18. 10.1375/twin.12.1.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk K. M., Maes H. H., Neale M. C., Heath A. C., Martin N. G., Eaves L. J. (1999). Frequency of church attendance in Australia and the United States: Models of family resemblance. Twin Research, 2(2), 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig L. B., McGue M., Iacono W. G. (2009). Rearing environmental influences on religiousness: An investigation of adolescent adoptees. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(6), 652–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. E., Matthews R. E., Morton A. S. (1954). Youth and political change. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 18(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Malka A., Lelkes Y., Soto C. J. (2017). Are cultural and economic conservatism positively correlated? A large-scale cross-national test. British Journal of Political Science, 49, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Martin N. D., Rigoni D., Vohs K. D. (2017). Free will beliefs predict attitudes toward unethical behavior and criminal punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 114(28), 7325–7330. 10.1073/pnas.1702119114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N. G., Eaves L. J., Heath A. C., Jardine R., Feingold L. M., Eysenck H. J. (1986). Transmission of social attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 83(12), 4364–4368. 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCourt K., Bouchard T. J., Jr., Lykken D. T., Tellegen A., Keyes M. (1999). Authoritarianism revisited: Genetic and environmental influences examined in twins reared apart and together. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(5), 985–1014. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R. R., Martin T. A., Hrebícková M., Urbánek T., Boomsma D. I., Willemsen G., Costa T. J. (2008). Personality trait similarity between spouses in four cultures. Journal of Personality, 76(5), 1137–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M., Keyes M., Sharma A., Elkins I., Legrand L., Johnson W., Iacono W. G. (2007). The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS). Behavior Genetics, 37(3), 449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson S., Cesarini D., Dawes C. T., Fowler J. H., Johannesson M., Magnusson P. K. E., Teorell J. (2015). Linking genes and political orientations: Testing the cognitive ability as mediator hypothesis. Political Psychology, 36(6), 649–665. [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson S., Dawes C. T., Lindgren K.-O. (2018). It runs in the family: A study of political candidacy among Swedish adoptees. Political Behavior, 40(4), 883–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R., DeFries J. C., Knopik V. S., Neiderhiser J. M. (2016). Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 3–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R., DeFries J. C., Loehlin J. C. (1977). Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 84(2), 309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman T. J., Benyamin B., De Leeuw C. A., Sullivan P. F., Van Bochoven A., Visscher P. M., Posthuma D. (2015). Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nature Genetics, 47(7), 702–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W. (2017). psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (Version 2.1.3) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Scarr S. (1981). The transmission of authoritarianism in families: Genetic resemblance in social-political attitudes? In Scarr S. (Ed.), Race, social class, and individual differences in I. Q. (pp. 399–427). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S., Weinberg R. A. (1978). The influence of “family background” on intellectual attainment. American Sociological Review, 43(5), 674–692. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J., Mitchell M., Haley H., Navarrete C. D. (2006). Support for harsh criminal sanctions and criminal justice beliefs: A social dominance perspective. Social Justice Research, 19(4), 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Davern M., Freese J., Morgan S. (2018). General social surveys, 1972–2018. https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/

- van Eerdewegh P. (1982). Statistical selection in multivariate systems with applications in quantitative genetics [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Washington University in St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Weeden J., Kurzban R. (2016). Do people naturally cluster into liberals and conservatives? Evolutionary Psychological Science, 2, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby E. A., McGue M., Iacono W. G., Lee J. J. (2021). Genetic and environmental contributions to IQ in adoptive and biological families with 30-year-old offspring. Intelligence, 88, Article 101579. 10.1016/j.intell.2021.101579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pss-10.1177_09567976211021844 for Parent Contributions to the Development of Political Attitudes in Adoptive and Biological Families by Emily A. Willoughby, Alexandros Giannelis, Steven Ludeke, Robert Klemmensen, Asbjørn S. Nørgaard, William G. Iacono, James J. Lee and Matt McGue in Psychological Science