Abstract

The nutritional and medicinal benefits of Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk. have led to its attention. Here, morphological and pomological diversity of this species was investigated. Most of the characters recorded showed considerable differences among the genotypes studied. The range of ripening data was from mid‐February to mid‐March. Fruit weight ranged between 15.68 and 33.62 g with an average of 24.17. Strong diversity was observed among the genotypes in terms of fruit skin ground color, ranging from light green to orange. There were significant correlations between some characters especially between the traits related to fruit size. Principal component analysis (PCA) classified the traits into 12 main components, justifying 75.07% of the total variance. The studied genotypes were grouped into two main clusters, indicating strong diversity among them. The present information might be used to choose the genotypes with the desired traits. Twenty‐one genotypes were promising because of high values of fruit weight, fruit taste, fruit skin color, and fruit quality, and thus, they can be recommended for direct cultivation and also to be used in breeding programs. The genotypes with superior traits can be further used for improvement through selection and hybridization to get desired traits.

Keywords: gene pool, morphological variation, quality, skin color, superior genotype

Twenty‐one genotypes of Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk. were promising because of high values of fruit weight, fruit taste, fruit skin color, and fruit quality, and thus, they can be recommended for direct cultivation and also be used in breeding programs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Indian jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk., Rhamnaceae family) is rich in nutritional and medicinal properties. Tropical regions of South Asia, Australia, and Africa are its main distribution centers (Pasternak et al., 2009). In the arid and semi‐arid regions, this plant is multipurpose and also can be used to prevent soil erosion (Gupta, 2018; Pareek, 2001). It has been confirmed that Indian jujube has high tolerance to salinity, drought, flooding, and withering (Grice, 1997). The medicinal and nutritional benefits of this plant have led to its attention. Vitamins are detected in its fruits. It is used as a sedative and anticancer. Also, it is suitable as wound healer and also against asthma (Ashraf et al., 2015; Hudina et al., 2008; Mishra et al., 2011; Nyanga et al., 2013). The antioxidant activity of its fruits (Gupta, 2018; Okala et al., 2014), seeds (Bhatia & Mishara, 2009), and leaf (Dahiru & Obidoa, 2007; Gupta, 2018) have been detected.

Self‐incompatibility and cross‐pollination have increased genetic variation of Indian jujube. There are superior genotypes in Z. mauritiana with high values for commercial characters that are cultivated in the orchard via asexual propagation methods (Devanshi et al., 2007). The breeding programs of plants need suitable genetic variation. Evaluation of genetic variability is essential for efficient application in breeding programs as well as for the implementation of conservation strategies. Lack of awareness of the genetic diversity and distribution of a plant species is one of the main obstacles to germplasm management. The study of genetic diversity is essential to identify distinct and superior genotypes, to explain the relationship between genotypes, and to manage and use germplasm properly (Awasthi et al., 2009; Hurtado et al., 2012).

The selection does not make diversity in germplasm because it creates small populations for breeders so that they can find ideal genotypes (Pommer, 2012). Choosing the suitable cultivar for successful cultivation with acceptable yield in specific areas is very important (Aulakhet al., 2000). The interaction between genetics and environment has an important function in expressing qualitative and also quantitative traits of a genotype. Morphological descriptions are still the first step in assessing the phenotypic diversity of plants helping breeders to identify genotypes with desired traits (Jannatabadi et al., 2014; Khadivi‐Khub et al., 2014).

The Z. mauritiana is distributed in the southern parts of Iran, but little research has been done on this species. Therefore, phenotypic diversity of this important species was performed for the selection of superior genotypes for cultivation. The obtained information can be also useful in the protection and management of the genotypes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant material

Here, 119 genotypes of Z. mauritiana were chosen from different areas of Sistan‐va‐Baluchestan province in the south of Iran, and then, their morphological and pomological variation was evaluated. The geographical characteristics of the sites studied are shown in Table 1. The selected genotypes are the most important cultivated trees in the study areas. The orchard management operations, including nutrition, irrigation, and pest and disease control, were performed regularly and uniformly for the genotypes.

TABLE 1.

Geographical description for collection sites of Z. mauritiana genotypes investigated from Sistan‐va‐Baluchestan province in Iran

| No. | Area | Longitude (E) | Latitude (N) | Height (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Molakarim | 61°25′48″ | 26°14′04″ | 252 |

| 2 | Talsar | 61°59′08″ | 26°12′14″ | 274 |

| 3 | Mandust | 61°57′44″ | 26°14′25″ | 254 |

| 4 | Soldan | 61°34′06″ | 26°14′46″ | 235 |

| 5 | Doshanbechah | 61°45′18″ | 26°18′14″ | 250 |

2.2. The recorded characteristics

Phenotypic variability of the genotypes was investigated based on 44 quantitative and qualitative characters related to tree, leaf, and fruit (Table 2). The 50 mature leaves and 50 mature fruits were used to record the related characters. A digital caliper was used to measure the characters related to dimensions of leaf and fruit. Also, an electronic balance with 0.01 g precision was used to measure the characters related to weights of fruit. The qualitative characters were recorded according to rating and coding (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics for morphological traits utilized in the studied Z. mauritiana genotypes

| No. | Character | Unit | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tree growth habit | Code | 1 | 5 | 2.29 | 1.18 | 51.57 |

| 2 | Tree growth vigor | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.44 | 1.17 | 33.98 |

| 3 | Tree height | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.20 | 1.18 | 36.75 |

| 4 | Branching | Code | 1 | 5 | 2.63 | 1.01 | 38.29 |

| 5 | Branch density | Code | 1 | 5 | 2.66 | 0.80 | 29.89 |

| 6 | Branch flexibility | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.87 | 0.50 | 17.53 |

| 7 | Trunk type | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.31 | 0.95 | 41.30 |

| 8 | Trunk diameter | Code | 1 | 5 | 2.87 | 0.62 | 21.71 |

| 9 | Trunk color | Code | 1 | 5 | 1.32 | 1.01 | 76.36 |

| 10 | Canopy density | Code | 1 | 5 | 2.53 | 1.10 | 43.32 |

| 11 | Tendency to form sucker | Code | 0 | 3 | 1.06 | 1.31 | 123.58 |

| 12 | Leaf density | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.82 | 0.58 | 20.64 |

| 13 | Leaf length | mm | 57.98 | 96.35 | 75.46 | 9.82 | 13.02 |

| 14 | Leaf width | mm | 35.02 | 75.95 | 49.54 | 9.52 | 19.22 |

| 15 | Petiole length | mm | 10.25 | 29.12 | 19.67 | 4.01 | 20.36 |

| 16 | Petiole width | mm | 1.19 | 2.87 | 1.92 | 0.36 | 18.76 |

| 17 | Leaf apex shape | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.24 | 0.97 | 43.48 |

| 18 | Leaf upper surface color | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.13 | 1.00 | 46.76 |

| 19 | Leaf lower surface color | Code | 1 | 3 | 2.33 | 0.95 | 40.73 |

| 20 | Leaf shape | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 21 | Leaf serration shape | Code | 1 | 3 | 1.32 | 0.74 | 55.76 |

| 22 | Leaf serration depth | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 23 | Leaf pubescence | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 24 | Shoot spine presence | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 25 | Ripening date | Date | Mid‐Feb | Mid‐March | 3.42 | 1.38 | 40.20 |

| 26 | Fruit density | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.05 | 1.57 | 51.54 |

| 27 | Fruit shape | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 1.77 | 49.55 |

| 28 | Fruit length | mm | 28.36 | 52.35 | 38.90 | 4.97 | 12.78 |

| 29 | Fruit width | mm | 26.29 | 43.56 | 33.76 | 3.69 | 10.92 |

| 30 | Fruit stalk length | mm | 6.35 | 22.32 | 11.75 | 4.32 | 36.79 |

| 31 | Fruit stalk diameter | mm | 0.97 | 1.68 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 13.60 |

| 32 | Fruit weight | g | 15.68 | 33.62 | 24.17 | 4.89 | 20.22 |

| 33 | Fruit skin ground color | Code | 1 | 9 | 5.82 | 2.01 | 34.48 |

| 34 | Fruit skin over color | Code | 1 | 9 | 4.16 | 2.95 | 70.96 |

| 35 | Fruit taste | Code | 1 | 7.00 | 5.62 | 1.91 | 33.97 |

| 36 | Fruit flesh firmness | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.72 | 1.30 | 34.81 |

| 37 | Fruit flesh thickness | mm | 9.94 | 17.69 | 13.71 | 1.44 | 10.50 |

| 38 | Flesh on fruit stone | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 39 | Fruit stone length | mm | 15.68 | 27.45 | 20.95 | 2.54 | 12.12 |

| 40 | Fruit stone width | mm | 8.18 | 13.54 | 10.03 | 1.39 | 13.86 |

| 41 | Fruit stone thickness | mm | 7.85 | 13.02 | 9.74 | 1.36 | 13.94 |

| 42 | Fruit stone weight | g | 0.76 | 2.52 | 1.52 | 0.53 | 34.50 |

| 43 | Fruit stone shape | Code | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 1.13 | 32.45 |

| 44 | Fruit stone surface | Code | 1 | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

TABLE 3.

Frequency distribution for the measured qualitative morphological characters in the studied Z. mauritiana genotypes

| Character | Frequency (no. of genotypes) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| Tree growth habit | ‐ | Weeping (49) | Spreading (63) | Open (7) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tree growth vigor | ‐ | Low (10) | Intermediate (73) | High (36) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tree height | ‐ | Low (15) | Intermediate (77) | High (27) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Branching | ‐ | Low (28) | Intermediate (85) | High (6) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Branch density | ‐ | Low (21) | Intermediate (97) | High (1) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Branch flexibility | ‐ | Low (8) | Intermediate (111) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Trunk type | ‐ | Single‐trunk (41) | Multitrunk (78) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Trunk diameter | ‐ | Low (10) | Intermediate (107) | High (2) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Trunk color | ‐ | Gray (107) | Gray‐brown (5) | Dark Gray (7) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Canopy density | ‐ | Low (35) | Intermediate (77) | High (7) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tendency to form sucker | Absent (63) | Low (21) | High (35) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Leaf density | ‐ | Low (11) | Intermediate (108) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Leaf apex shape | ‐ | Blate (45) | Acute (74) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Leaf upper surface color | ‐ | Green (52) | Dark green (67) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Leaf lower surface color | ‐ | Light green (40) | Silver‐green (79) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Leaf serration shape | ‐ | Serrate (100) | Crenate (19) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ripening date | ‐ | Mid‐Feb (18) | Early‐March (58) | Mid‐March (43) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fruit density | ‐ | Low (35) | Intermediate (46) | High (38) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fruit shape | ‐ | Globose (34) | Ovate (17) | Ellipsoid (68) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fruit skin ground color | ‐ | Light green (6) | Green (20) | Cream (19) | Yellow (67) | Orange (7) |

| Fruit skin over color | ‐ | Green (41) | Cream (19) | Yellow (30) | Orange (7) | Red (22) |

| Fruit taste | ‐ | Sour (6) | Sour‐sweet (23) | Slightly sweet (18) | Sweet (72) | ‐ |

| Fruit flesh firmness | ‐ | Low (11) | Intermediate (54) | High (54) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fruit stone shape | ‐ | Ellipsoid (8) | Ovate (75) | Elongated (36) | ‐ | ‐ |

2.3. Data analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, & USA, 1990). Simple correlations between the traits were done using Pearson correlation coefficient with SPSS software (PSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; Norusis, 1998). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to study the relationships among the genotypes with SPSS software. Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed using Ward's method and Euclidean distance with PAST software (Hammer et al., 2001). Also, the scatter plot was created using the first and second principal components (PC1/PC2) with PAST software.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Description of characteristics

Considerable diversity was observed among the studied genotypes, as revealed by the characteristics recorded. The tendency to form sucker exhibited the greatest CV (123.58%). Also, trunk color (76.36%), fruit skin over color (70.96%), leaf serration shape (55.76%), tree growth habit (51.57%), and fruit density (51.54%) showed high CVs. Besides, the CV was more than 20.00% in the majority of characters recorded (63.36% of characters) and thus revealed significant diversity within the germplasm studied (Table 2). In contrast, six characters did not show differences, including leaf shape (lanceolate), leaf serration depth (low), leaf pubescence (present), shoot spine (present), fruit stone flesh (present), and surface of fruit stone (coarse), and thus, they can be considered as stable traits. Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and reported that canopy density, color leaf lower surface, color of leaf upper surface, leaf shape, petiole length, fruit shape, fruit weight, and fruit stone shape showed high CVs.

The tree growth habit was variable and included weeping (49 genotypes), spreading (63), and opening (7). Sharif et al. (2019) studied the growth habit of Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and observed that tree growth habit was spreading in the most of genotypes. Also, the majority of studied genotypes exhibited moderate values for other tree‐related characters (Table 3). Gupta (2018) studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India and reported high variation in the tree‐related traits in the germplasm investigated.

Two types of leaf apex shape were recorded, including blate (45 genotypes) and acute (74). Leaf serration shape was predominantly serrated (100 genotypes). The range of leaf length was from 57.98 and 96.35 mm, while the range of leaf width was between 35.02 and 75.95 mm. Petiole length and width ranged from 10.25 to 29.12 mm and 1.19 to 2.87 mm, respectively (Table 2). Gupta (2018) studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India and reported the range of 74.20–130.00 mm for leaf length, 56.00–87.70 mm for leaf width, and 14.70–31.70 mm for petiole length. Also, Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and reported the range of 18.00–91.00 mm for leaf length and 14.00–66.00 mm for leaf width. The variability in the tree‐ and leaf‐related characters is mainly due to inherent characteristics (Gupta, 2018).

The ripening date ranged from mid‐February to mid‐March. Fruit density was low in 35, intermediate in 46, and high in 38 genotypes. Fruit shape was predominantly ellipsoid (68 genotypes) (Table 3). Gupta (2018) studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India and reported high variation among the genotypes in terms of fruit shape. Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and reported that round fruit shape was predominant. Fruit length and width ranged as follows: 28.36–52.35 mm and 26.29–43.56 mm, respectively. Also, fruit weighted between 15.68 and 33.62 g with an average of 24.17 (Table 2). Gupta (2018) studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India and recorded the range of 22.00–50.52 mm for fruit length, 19.40–36.20 mm for fruit width, and 5.60–27.31 g for fruit weight. Also, Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and recorded the range of 8.83–48.86 mm for fruit length, 11.03–41.14 mm for fruit width, and 1.88–38.45 g for fruit weight. Fruit flesh thickness ranged from 9.94 to 17.69 mm, and fruit flesh percentage varied from 89.87 to 96.81%. Gupta (2018) recorded the range of 91.81–95.94% for fruit flesh percentage in the studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India.

Fruit skin ground color showed high variability and was predominantly yellow (67 genotypes). Gupta (2018) observed the range of yellowish‐green to light brown in Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India. Sweet taste (72 genotypes) was predominant in the germplasm. The firmness of fruit flesh was high and intermediate in 54 and 54 genotypes, respectively, while it was low only in 11 genotypes. Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and reported the range of low to high for fruit flesh firmness.

The mean value of length, width, and thickness of fruit stone was 20.95, 10.03, and 9.74 mm, respectively. The weight of fruit stone ranged from 0.76 to 2.52 g. Gupta (2018) recorded the range of 0.39–1.42 g for weight of fruit stone in the studied Z. mauritiana from Punjab in India. Also, Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and observed that the weight of fruit stone was 0.32–1.84 g. Fruit stone shape was predominantly ovate (75 genotypes). Sharif et al. (2019) recorded that round fruit stone shape was predominant in Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan. The fruit and leaf pictures of Z. mauritiana genotypes studied are presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The pictures of leaves and fruits of Z. mauritiana genotypes studied, including a) Farzadi, b) Soopi, c) Sibi‐Ghermez, d) Sibi‐Sefid, and e) Behzadi

3.2. Simple correlations between the characteristics

Pearson correlation analysis showed significant relationships between some characters (data not shown). Leaf length showed positive and significant correlations with leaf width (r = 0.86), petiole length (r = 0.63), and petiole width (r = 0.66) and agreed with the previous studies in Ziziphus jujuba (Khadivi et al., 2021; Norouzi et al., 2017) and Z. mauritiana (Sharif et al., 2019). Fruit density showed significant and positive correlations with tree growth vigor (r = 0.39), tree height (r = 0.25), branching (r = 0.31), branch density (r = 0.25), canopy density (r = 0.48), and leaf density (r = 0.27) and agreed with the previous studies in Z. jujuba (Khadivi et al., 2021; Norouzi et al., 2017) and Z. mauritiana (Sharif et al., 2019). Fruit weight was highly and positively correlated with fruit length (r = 0.54), fruit width (r = 0.73), fruit stalk length (r = 0.23), fruit stone length (r = 0.47), fruit stone width (r = 0.54), fruit stone thickness (r = 0.49), and fruit stone weight (r = 0.63) and agreed with the previous studies in Z. jujuba (Khadivi et al., 2021; Norouzi et al., 2017) and Z. mauritiana (Sharif et al., 2019).

3.3. PCA

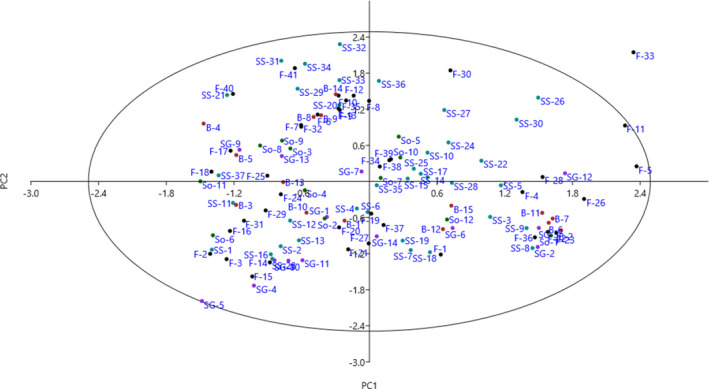

The PCA is used to find the most important traits in the data set. The purpose of the PCA is to identify a number of key components to reduce the number of characters influencing the differentiation of genotypes (Iezzoni & Pritts, 1991). Also, the relationship between the traits emphasized by this method may be consistent with the genetic link between the trait control position and the multifunctional effect (Khadivi‐Khub et al., 2014). The PCA classified the traits into 12 main components, justifying 75.07% of the total variance (Table 4). Sharif et al. (2019) studied Z. mauritiana genotypes from Pakistan and reported that PCA placed the characters into six PCs with explaining 82.05% of the total variance. The PC1, accounting for 16.46% of the total variance, was associated with fruit length, fruit width, fruit weight, fruit flesh firmness, fruit stone length, fruit stone width, fruit stone thickness, and fruit stone weight and agreed with the findings of Sharif et al. (2019). Six characters, including tree growth vigor, tree height, branching, branch density, canopy density, and fruit density, were placed into PC2 and accounted for 9.33% of the total variance. Four characteristics, including leaf length, leaf width, petiole length, and petiole width, were correlated with PC3, which accounted for 9.28% of the total variance. The scatter plot created using PC1 and PC2 showed the phenotypic diversity among the genotypes (Figure 2). The genotypes were distributed on the plot and were divided into two groups with four subgroups.

TABLE 4.

Eigenvalues of the principal component axes from the PCA of morphological characters in the studied Z. mauritiana genotypes

| Character | Component | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Tree growth habit | 0.25 | −0.25 | −0.25 | 0.10 | 0.13 | −0.03 | −0.55** | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.36 | −0.28 | −0.08 |

| Tree growth vigor | −0.18 | 0.71** | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.29 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.12 |

| Tree height | 0.07 | 0.74** | −0.02 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.27 | 0.07 | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.17 |

| Branching | −0.09 | 0.80** | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Branch density | 0.01 | 0.73** | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.24 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.13 |

| Branch flexibility | −0.12 | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.70** | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| Trunk type | −0.14 | 0.03 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.35 | 0.02 | −0.18 | −0.57** | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.36 |

| Trunk diameter | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.29 | 0.62** | −0.09 | −0.02 | −0.13 | 0.22 |

| Trunk color | 0.10 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.82** |

| Canopy density | −0.02 | 0.64** | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.12 | −0.08 | −0.18 |

| Tendency to form sucker | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.89** | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Leaf density | 0.08 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.07 | −0.30 | −0.31 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.16 | 0.08 |

| Leaf length | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.91** | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Leaf width | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.89** | −0.24 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.02 |

| Petiole length | −0.11 | −0.15 | 0.80** | 0.16 | −0.35 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.06 |

| Petiole width | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.82** | 0.07 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.11 |

| Leaf apex shape | 0.25 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.76** | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.02 | −0.08 |

| Leaf upper surface color | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.26 | 0.27 | −0.12 | 0.11 | 0.68** | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Leaf lower surface color | 0.03 | −0.16 | −0.24 | 0.27 | −0.10 | 0.37 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 0.23 |

| Leaf serration shape | −0.12 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.19 | 0.15 | −0.12 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.43 | −0.50 | 0.24 | 0.34 |

| Ripening date | −0.02 | −0.19 | −0.05 | −0.11 | 0.74** | −0.01 | 0.18 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.14 | −0.09 | 0.15 |

| Fruit density | 0.28 | 0.58** | −0.07 | −0.14 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.10 | −0.05 | −0.24 |

| Fruit shape | 0.25 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.68** | 0.23 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.23 | −0.34 | 0.04 |

| Fruit length | 0.88** | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Fruit width | 0.79** | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.21 | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.15 | −0.21 | 0.31 | 0.02 |

| Fruit stalk length | 0.54 | −0.06 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.63** | −0.09 | 0.13 |

| Fruit stalk diameter | 0.41 | −0.02 | 0.47 | −0.21 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.04 |

| Fruit weight | 0.65** | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.19 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.23 | −0.01 |

| Fruit skin ground color | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.86** | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 |

| Fruit skin over color | −0.23 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.14 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.65** | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Fruit taste | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.85** | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Fruit flesh firmness | 0.67** | −0.18 | 0.02 | 0.21 | −0.34 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.21 | 0.09 | −0.05 | −0.22 | −0.15 |

| Fruit flesh thickness | 0.19 | −0.05 | −0.13 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.84** | 0.02 |

| Fruit stone length | 0.82** | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.00 | 0.18 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.25 | −0.08 | 0.15 |

| Fruit stone width | 0.95** | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Fruit stone thickness | 0.93** | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.12 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Fruit stone weight | 0.73** | 0.05 | −0.20 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.12 | −0.20 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.03 | −0.10 |

| Fruit stone shape | 0.04 | 0.16 | −0.13 | 0.24 | 0.62** | 0.01 | −0.33 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.31 | 0.18 | −0.18 |

| Total | 6.25 | 3.54 | 3.53 | 1.95 | 1.94 | 1.88 | 1.74 | 1.65 | 1.64 | 1.63 | 1.43 | 1.36 |

| % of Variance | 16.46 | 9.33 | 9.28 | 5.12 | 5.11 | 4.94 | 4.58 | 4.33 | 4.32 | 4.28 | 3.75 | 3.58 |

| Cumulative % | 16.46 | 25.79 | 35.06 | 40.19 | 45.30 | 50.23 | 54.81 | 59.15 | 63.46 | 67.74 | 71.49 | 75.07 |

** Eigenvalues ≥0.55 are significant at the p ≤ .01 level.

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plot for the studied Z. mauritiana genotypes based on PC1/PC2. The symbols represent the replications of each genotype in the plot, including Farzadi (F), Sibi‐Ghermez (SG), Behzadi (B), Sibi‐Sefid (SS), and Soopi (So)

3.4. HCA

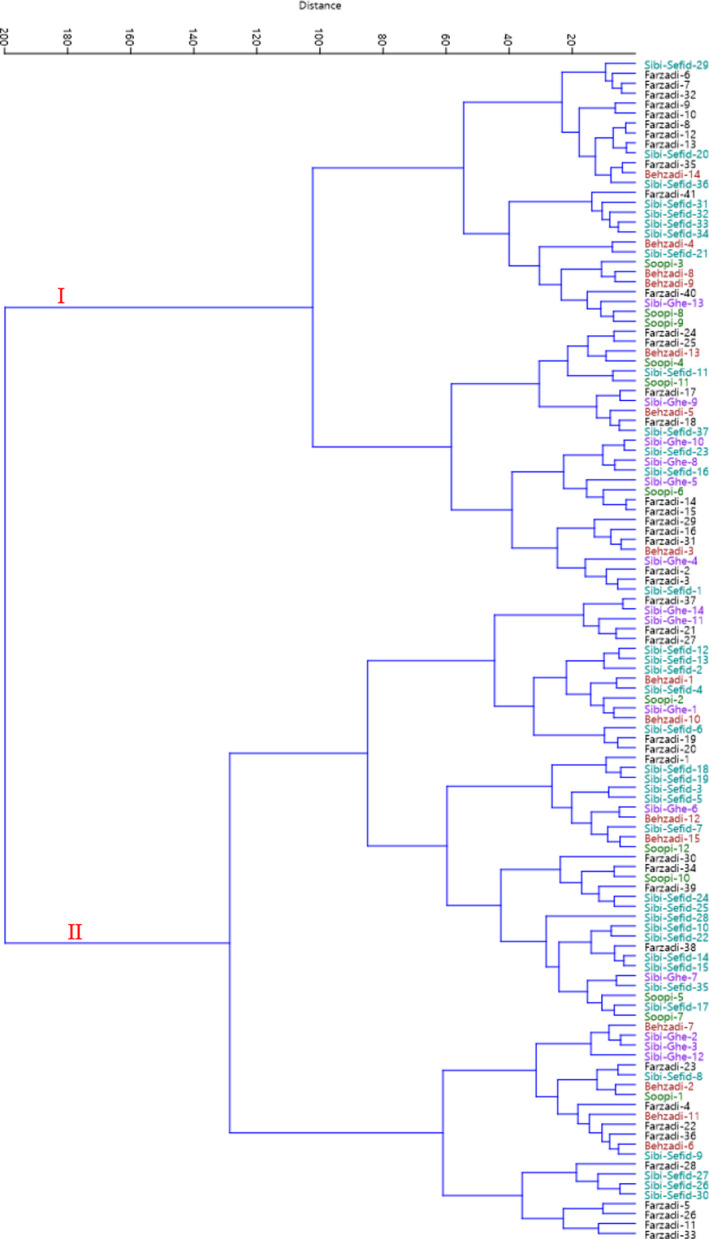

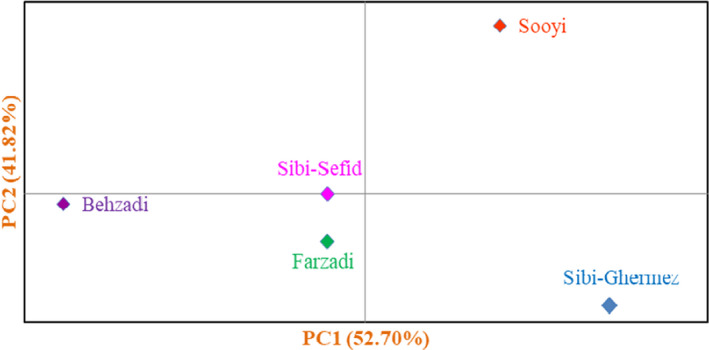

The genotypes studied were placed into two major clusters according to all the traits using HCA (Figure 3). The first cluster (I) included two subclusters. Subcluster I‐A consisted of 27 genotypes, and subcluster I‐B contained 27 genotypes. The remaining genotypes were classified into the second cluster (II), forming two subclusters. Subcluster II‐A consisted of 43 genotypes, and subcluster II‐B contained 22 genotypes. Besides, population analysis showed that the studied populations were divided into three main groups (Figure 4). The first group included Soopi population, characterized by the lowest values for leaf length and leaf width and also the highest value for fruit weight. The second group consisted of Sibi‐Ghermez population, characterized by the lowest values for fruit length, fruit width, fruit stalk length, fruit stalk diameter, fruit weight, fruit stone length, fruit stone width, fruit stone thickness, and fruit stone weight. Also, the third group included Behzadi, Farzadi, and Sibi‐Sefid populations, characterized by high values for leaf, fruit, and stone. The genotypes with desirable values for fruit yield and fruit quality are always selected by breeder for using in breeding programs and also for cultivation (Mahmood et al., 2014). Here, phenotypic diversity was considerable among the genotypes selected, which can be used to begin the comprehensive investigations on genetic resources of Z. mauritiana and to select the promising genotypes for cultivation.

FIGURE 3.

Ward cluster analysis of the studied Z. mauritiana genotypes based on morphological traits using Euclidean distances

FIGURE 4.

Biplot for the studied populations of Z. mauritiana based on morphological characters

The diversity observed in the fruit size and quality‐related characteristics between the studied genotypes can encourage the implementation of breeding programs. The results also showed that fruit weight among different genotypes has considerable diversity. The variation in fruit weight among the genotypes grown in the same geographical areas is due to differences in genetic basis and ecological conditions (Umbreen et al., 2018). The genotypes with high fruit weight can be selected for fresh fruit production and introduction to growers. The length and width of the fruit, which are important traits for breeders, also showed considerable diversity. The study of fruit size‐related traits is of great importance for packaging and shipping judgments. Also, the color and taste of the fruits of different genotypes showed a great diversity, which can help breeders to choose genotypes according to the type of consumption (Liu et al., 2009).

4. CONCLUSION

The current findings can be widely used to introduce cultivars in breeding programs of Z. mauritiana. The present information might be used to choose the genotypes with the desired traits. Finally, 21 genotypes, including Sibi‐Sefid‐35, Farzadi‐41, Farzadi‐40, Sibi‐Sefid‐34, Sibi‐Sefid‐33, Sibi‐Sefid‐32, Behzadi‐9, Behzadi‐8, Soopi‐3, Sibi‐Sefid‐37, Soopi‐9, Farzadi‐30, Farzadi‐4, Soopi‐5, Sibi‐Ghermez‐13, Sibi‐Sefid‐10, Sibi‐Sefid‐22, Farzadi‐12, Soopi‐7, Sibi‐Sefid‐30, and Sibi‐Ghermez‐7, were promising because of high values for fruit weight, fruit taste, fruit skin color, and fruit quality that might be directly cultivated and used in breeding programs. Besides, the genotypes with superior traits can be further used for improvement through selection and hybridization to get desired traits.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Farhad Mirheidari: Investigation (equal). Ali Khadivi: Formal analysis (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead). Abdolvahid Saeidifar: Investigation (equal). Younes Moradi: Investigation (equal).

RESEARCH INVOLVING HUMAN PARTICIPANTS AND/OR ANIMALS

None.

INFORMED CONSENT

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Mirheidari, F. , Khadivi, A. , Saeidifar, A. , & Moradi, Y. (2022). Selection of superior genotypes of Indian jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk.) as revealed by fruit‐related traits. Food Science & Nutrition, 10, 903–913. 10.1002/fsn3.2721

Funding information

None

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Ashraf, A. , Sarfraz, R. A. , Anwar, F. , Shaukat Ali Shahid, S. A. , & Alkharfy, K. M. (2015). Chemical composition and biological activities of leaves of Ziziphus mauritiana L. native to Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 47(1), 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, P. S. , Mehotra, N. K. , & Vij, V. K. (2000). Performance of ber varieties grown under rainfed conditions in Punjab. Indian Journal of Horticulture, 57(2), 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, O. P. , More, T. A. , & Liu, M. J. (2009). Genetic diversity and status of Ziziphus in India. Acta Horticulture, 840, 33–40. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.840.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, A. , & Mishra, T. (2009). Free radical scavenging and antioxidant potential of Ziziphus mauritiana (Lamk.) seed extract. Journal of Complementary Integrative Medicine, 8, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiru, D. , & Obidoa, O. (2007). Pretreatment of albino rats with aqueous leaf extract of Ziziphus mauritiana protects against alcohol induced liver damage. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 6, 705–710. [Google Scholar]

- Devanshi, S. A. K. , Sharma, P. , Singh, B. , Singh, R. , & Singh, N. K. (2007). Molecular profiling and genetic relationship among ber (Ziziphus sp.) genotypes using RAPD markers. Indian Journal of Genetics, 67(2), 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, A. C. (1997). Post‐fire regrowth and survival of the invasive tropical shrubs Cryptostegia grandiflora and Ziziphus mauritiana . Australian Journal of Ecology, 22(1), 49–55. 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1997.tb00640.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N. (2018). Morphological and physico‐chemical characterization of ber (Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk.) genotypes in semi‐arid zone of Punjab. International Journal of Chemical Studies, 6(5), 2353–2356. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø. , Harper, D. A. T. , & Ryan, P. D. (2001). PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica, 4(1), 9. http://palaeoelectronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm [Google Scholar]

- Hudina, M. , Liu, M. , Veberic, R. , Stampar, F. , & Colaric, M. (2008). Phenolic compounds in the fruit of different varieties of Chinese jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.). Journal of Horticultural Science Biotechnology, 83, 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, M. , Vilanova, S. , Plazas, M. , Gramazio, P. , Fonseka, H. H. , Fonseka, R. , & Prohens, J. (2012). Diversity and relationships of eggplants from three geographically distant secondary centers of diversity. PLoS One, 7, e41748. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni, A. F. , & Pritts, M. P. (1991). Applications of principal component analysis to horticultural research. HortSci, 26, 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Jannatabadi, A. A. , Talebi, R. , Armin, M. , Jamalabadi, J. G. , & Baghebani, N. (2014). Genetic diversity of Iranian landrace chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) accessions from different geographical origins as revealed by morphological and sequence tagged microsatellite markers. Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 23, 225–229. 10.1007/s13562-013-0206-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khadivi, A. , Mirheidari, F. , Moradi, Y. , & Paryan, S. (2021). Identification of superior jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) genotypes based on morphological and fruit characterizations. Food Sciences and Nutrition, 9, 3165–3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadivi‐Khub, A. , Salimpour, A. , & Rasouli, M. (2014). Analysis of grape germplasm from Iran based on fruit characteristics. Brazilian Journal of Botany, 37(2), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. , Liu, M. J. , Zhao, Z. H. , Liu, X. Y. , Wang, J. R. , & Yan, C. (2009). Investigation on the characteristics of fruiting and seed development in Chinese jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.). Acta Horticulturae, 84, 209–214. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.840.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A. , Jaskani, M. J. , Khan, I. A. , Ahmad, S. , Ahmad, R. , Luo, S. , & Ahmad, N. M. (2014). Genetic diversity of Pakistani guava (Psidium guajava L.) germplasm and its implications for conservation and breeding. Scientia Horticulturae, 222, 180–186. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, T. , Khullar, M. , & Bhatia, A. (2011). Anticancer potential of aqueous ethanol seed extract of Ziziphus mauritiana against cancer cell lines and enrich ascites carcinoma. Evidence based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Article ID:765029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, E. , Erfani‐Moghadam, J. , Fazeli, A. , & Khadivi, A. (2017). Morphological variability within and among three species of Ziziphus genus using multivariate analysis. Scientia Horticulturae, 222, 180–186. 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.05.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis, M. J. (1998). SPSS/PC advanced statistics. SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanga, L. K. , Gadaga, T. H. , Nout, M. J. R. , Smid, E. J. , Boekhout, T. , & Zwietering, M. H. (2013). Nutritive value of masau (Ziziphus mauritiana) fruits from Zambezi Valley in Zimbabwe. Food Chemistry, 138(1), 168–172. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okala, A. , Ladan, M. J. , Wasagu, R. S. U. , & Shehu, K. (2014). Phytochemical studies and in vitro antioxidant properties of Ziziphus mauritiana fruit extract. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research, 6(4), 885–888. [Google Scholar]

- Pareek, O. P. (2001). Fruits for the future 2: Ber, International Centre for Underutilized Crop. Redwood Books, Wiltshire, p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, D. , Senbeto, D. , Nikiema, A. , Kumar, S. , Fatondji, D. , Woltering, L. , Ratnadass, A. , & Ndjeunga, J. (2009). Bioreclamation of degraded African lands with women empowerment. Chronica Horti, 49(2), 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pommer, C. V. (2012). Guava world‐wide breeding: Major techniques and cultivars and future challenges. Acta Horticulture, 959, 81–88. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2012.959.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS® Procedures (1990). Version 6, 3rd ed. SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, N. , Jaskani, M. J. , Naqvi, S. A. , & Awan, F. S. (2019). Exploitation of diversity in domesticated and wild ber (Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk.) germplasm for conservation and breeding in Pakistan. Scientia Horticulturae, 249, 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Umbreen, S. , Jaskani, M. J. , Saeed, M. , Awan, F. S. , & Naqvi, S. A. (2018). Genetic divergence of Moringa oleifera, economically important, yet an endangered species from Pakistan. International Journal of Agricultural Biology, 20, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.