Abstract

Background

Delay in seeking emergency obstetric care contributes to high maternal mortality and morbidity in developing countries. One of the major factors contributing to maternal death in developing countries is a delay in seeking emergency obstetric care. This study aimed to assess the proportion and associated factors of delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care on institutional delivery among postpartum mothers in the South Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

Methods

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from September to October 2020. A total of 650 postpartum mothers were recruited using a systematic random sampling technique. We collected the data through personal interviews with pretested semi-structured questionnaires. We used a logistic regression model to identify statistically significant independent variables, and entered the independent variables into multivariable logistic regression. The Adjusted Odds Ratio was used to identify associated variables with delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care, with a 95% confidence interval at P-value < 0.05.

Results

The proportion of delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care on institutional delivery was 36.3% (95% CI: 32.6–40.1). The mean age of the respondents was 27.23, with a standard deviation of 5.67. Mothers who reside in rural areas (AOR = 3.14,95%, CI:2.40–4.01), uneducated mothers (AOR = 3.62, 95%, CI:2.45–5.52), unplanned pregnancy (AOR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.84–7.96), and no health facilities in Kebele (AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.43–6.32) were significantly associated with delay in a decision to seek emergency obstetric care.

Conclusion

The proportion of delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care was 36.3% among postpartum mothers in the South Gondar zone hospitals. One of the factors contributing to maternal death is a delay in seeking emergency obstetric care in South Gondar zone. Pregnant mothers living in the rural area, unplanned pregnancy, uneducated mothers, no health facilities in Kebele were associated factors in the study area. Therefore, stakeholders must address them to reduce the proportion of delay in deciding to receive on-time obstetric care as per the standards.

Keywords: Delay, Decision, Emergency obstetrics care, Factors, Institution

Delay; Decision; Emergency obstetrics care; Factors; Institution.

1. Introduction

Maternal mortality and morbidity are serious public health concern that have a devastating impact on children, families, and communities worldwide [1, 2, 3]. Despite significant efforts with limited resources, maternal morbidity and mortality remain high in developing countries. The health condition of postpartum mothers is deteriorated due to the delay in making a decision. They die at home, at the hands of their families on the road, in the health care facility, and survive with long-term complications. The time it takes to get to healthcare facilities due to delay in a decision making contributes to maternal morbidity and mortality [4, 5, 6]. Studies found that mothers who delayed seeking care experienced various health issues for both the mother and the neonate, including antepartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, and uterine rupture [7, 8, 9, 10]. The perceived inequity in care they received, a shortage of skilled health professionals, geographical inaccessibility, and disrespectful service delivery by health care providers contribute to women not seeking health facility care [11,12]. On the other hand, one element affecting access to professional health care is a woman's poor understanding of pregnancy danger signs that demand early and competent medical attention. The family members cannot access appropriate emergency obstetric care are difficult for women who cannot make autonomous decisions about their health [9,13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. The Ethiopian government has been working hard to reduce maternal and child mortality by improving health services to reach rural and poorer populations in health promotion, disease prevention, and curative services. However, specific strategies and synergistic intervention at all levels are further required to improve and save the lives of mothers and their families. Stakeholders should emphasize the health of rural mothers, uneducated mothers, mothers who have unplanned pregnancies, and mothers who live far from healthcare facilities. Finally, we suggest other researchers investigate unreachable and unspoken causes that contributed to the delay in making decisions to seek care at the community level.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and period

Health facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted in South Gondar zone hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, from September to October 2020.

2.2. Study area

The study was conducted in the South Gondar zone hospitals in the Amhara Region, Northwest, Ethiopia. Debre Tabor is the capital city of the zone, located at 103 km from Bahir Dar (the capital city of Amhara Regional State) and approximately 667 km from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia). According to a report from the south Gondar zone administrative office, the population of this zone is 2,609,823. Among which the females’ population is 1304,911. The majority is economically dependent on agriculture. One referral hospital and seven additional governmental hospitals (Mekane-Eyesus, Andabet, Nifas-Mewucha, Addis-Zemen, Tach Gait, Wogeda, and Event). The zone has 96 public health centers, 140 private clinics, and 403 health posts.

2.3. Source population

All postpartum mothers who gave birth in South Gondar zone hospitals in 2020.

2.4. Study population

All postpartum mothers who gave birth in South Gondar zone hospitals during a data collection period.

2.5. Inclusion criteria

All postpartum mothers who gave birth among selected hospitals in the South Gondar zone and resided in the study area for at least six months.

2.6. Exclusion criteria

Pregnant mothers who were admitted before the onset of labor for observation in the waiting room, considering they would have a better understanding of information exposure.

2.7. Study variables

Dependent variable: Delay in making the decision.

Independent variables include age, residence, marital status, ethnicity, religion, mother's education, husband's education, mother's occupation, husband's occupation, and family income. Obstetric variables include gravidity, parity, ANC follow-up, type of pregnancy, previous mode of delivery, and current mode of delivery. Factors affecting health care facilities include the availability of health care, the distance between health care facilities, modes of transportation, previous pregnancy birthplace, knowledge of any danger signs of labor, and the decision-maker for EOC [18,19].

2.8. Operational definition

Institutional delivery utilization: when a mother gave birth at a healthcare facility.

Delay in making a decision: The time elapsed between the recognition of labor and the decision to seek institutional delivery service. Time spent more than one hour deciding to seek care was considered a delay [14].

2.9. Sample size determination

Using a single population proportion formula, we determined the sample size using the following assumptions: a) the proportion of delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care was 26.2% [10], b) 5% margin of error, and c)10% non-response rate. A multistage sampling procedure required us to use a design effect of 2. We arrived at the final required sample size of 653 study participants.

2.10. Sampling procedure and technique

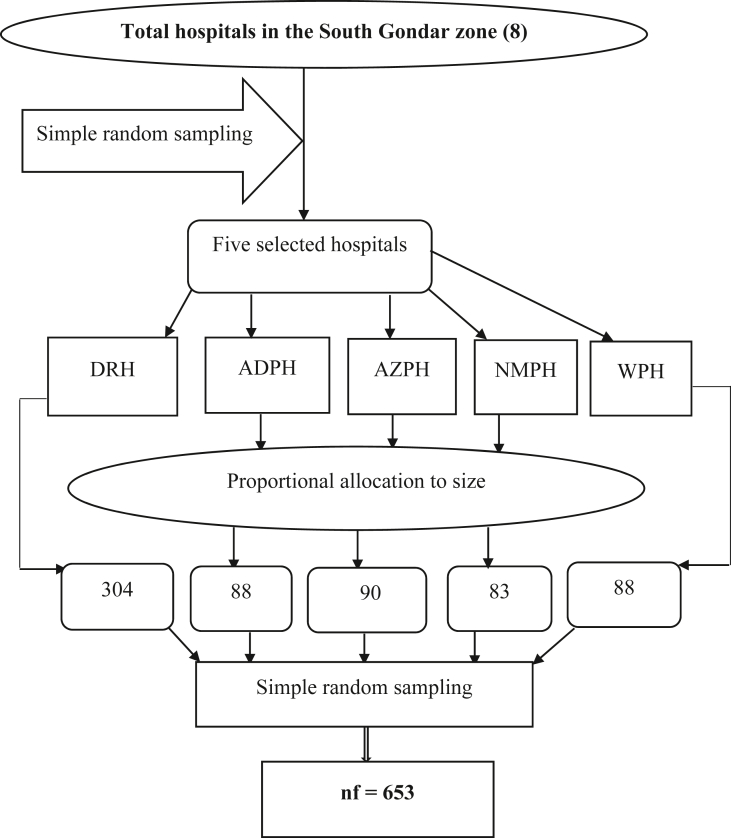

The total sample size was proportionally allocated to five randomly selected hospitals in the south Gondar zone. The first participant was selected randomly; then, the subsequent participants were selected by a systematic sampling technique, every two intervals for all study participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure among mothers in South Gondar zone hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020. NB: DTGH: Debre Tabor referral hospital, APH: Andabet primary hospital, AZPH: Addis Zemen primary hospital, NMPH: Nifas Mewucha primary hospital, WPH: Wogeda primary hospital.

2.11. Data collection techniques

The data were collected through personal interviews with postpartum mothers in a private room before discharge. Five diploma midwives and two midwifery professionals were recruited for data collection supervision, respectively. The questionnaires were prepared in English and then translated to Amharic (local language) for simplicity and back to English to maintain the consistency of the tool.

2.12. Data quality assurance

The questionnaire was pretested to check participant response, language clarity, and appropriateness of the questionnaires. A pretest was conducted on 5% of the study participants at Koladiba primary hospital. At the end of the pretest, ambiguous and culturally sensitive questions were amended, clarified, and adjusted before data collection began. We gave a one-day training for data collectors and supervisors to clarify the purpose of the study and data collection methods. We checked the collected data daily for its completeness and consistency, kept it locked in a file cabinet, and were accessible only for the researchers.

2.13. Data processing, analysis, and interpretation

The coded data double entered into Epi-data version 3.1, exported it to Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS) version 23.00 for data checking, cleaning, and analysis. We presented statistical values using frequency, mean, and proportion to describe the study population. The results of the study are presented in the text and tables. We considered an extraneous variable that is statistically related to (or correlated with) the independent variable. Failing to take a confounding variable into account can lead to a false conclusion that the dependent variables have a causal relationship with the independent variable. For this purpose, we used a logistic regression model to identify statistically significant independent variables. We entered the independent variables into multi variable logistic regression to adjust confounding variables (p-value <0.2). The Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) was used to identify associated variables with delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care, with a 95% CI at p-value < 0.05.

2.14. Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, which outlines ethical criteria to be followed while doing research on human participants We obtained the study approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Gondar on behalf of the Ethical Review Committee of the midwifery school with a Ref No. MIDW/h/34/09/2011. We also obtained a letter of permission from the Amhara region health office. We explained the reason to the study participants for conducting the research, verbal informed consent after explaining the purpose of the study, due to the approval of the ethical committee that the research did not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the participants. Any women who were not willing to participate in the study were not forced to participate. All data taken from the participants were kept strictly confidential and used only for the study purpose.

3. Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the study participants: A total of 650 postpartum mothers participated in the study with a response rate of 99.54%. Approximately 78.6% were found in the age group 20–34 years. Around 34.5% of participants lived in rural areas, and 96.8% were orthodox Christianity religion followers. Of the study participants, 20.6% were housewives, 29.4% could not read and write. More than one-fourth (26.9%) of them have attended college and above the educational level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants among postpartum mothers in the South Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the mothers (years) | <20 20–34 ≥35 |

85 511 54 |

13.1 78.6 8.3 |

| Residence | Urban Rural |

426 224 |

65.5 34.5 |

| Marital status of the mothers | Married Others∗ |

644 6 |

99.1 0.9 |

| Religion | Orthodox Muslims |

629 19 |

96.8 2.9 |

| Protestant | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Education of the mothers | Unable to read and write Grade 1 -8 Grade 9-12 College and above |

191 181 103 175 |

29.4 27.8 15.8 26.9 |

| Occupation status of the mothers | Housewife Employed Merchant Student Farmer Daily laborer |

134 314 77 33 55 37 |

20.6 48.3 11.8 5.1 8.5 5.7 |

| Education of husband | Unable to read and write Grade 1 -8 Grade 9-12 College and above |

140 183 40 244 |

21.5 28.3 12.3 37.5 |

| Occupation of husband (n = 647) | Employed Merchant Student Farmer Daily laborer |

202 181 43 177 26 |

33.6 28.7 6.6 27.1 4.0 |

| Family monthly income | ≤1000 1001–1999 ≥2000 |

141 132 377 |

21.7 20.3 58.0 |

∗single and divorced, ∗∗: Muslim and Protestant.

Obstetrics factors: From the total participants, 50.8% of the participants were prim-para. Among the study participants, 22.2% had no history of antenatal follow-up in their current delivery, and 15.2% did not know the danger signs of labor. Among those who had a birth history, 65.9% had recent delivery at a healthcare facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetrics factors of the study participants among postpartum mothers in South the Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravida | Prim gravida Multigravida Grand multigravida |

330 194 126 |

50.8 29.8 19.4 |

| Parity | 1 2–4 ≥5 |

315 208 130 |

48.5 31.5 20.0 |

| ANC visits | yes no |

506 144 |

77.8 22.2 |

| Planned pregnancy | Yes No |

242 408 |

37.2 62.8 |

| Wanted pregnancy | Yes No |

621 29 |

95.5 4.5 |

| Previous home delivery (n = 347) | Yes No |

171 176 |

49.29 50.71 |

| Readiness to deliver in the health institution | Yes No |

527 123 |

81.1 18.9 |

| Knowledge of danger signs of labor (at least one) | Yes No |

551 99 |

84.8 15.2 |

| Pregnancy outcome | Live birth Stillbirth |

615 35 |

94.6 5.4 |

| Time of labor onset | Day Night | 392 258 |

60.7 39.3 |

| Birth weight of the baby | <2500 g 2500–4000 g ≥4000 g |

76 556 18 |

11.7 85.5 2.8 |

| Number of children | one 2-4 children ≥5 children |

328 268 54 |

50.5 41.2 8.3 |

| Mode of delivery in the past (n = 322) | SVD Instrumental delivery CS |

282 10 30 |

87.6 3.1 9.3 |

| Current mode of delivery | SVD Instrumental delivery c/s |

546 41 63 |

84.0 6.3 9.7 |

| Complication of after delivery | Yes No |

57 593 |

8.8 91.2 |

Health facility factors: In this study, 87 (13.4%) of the participants had no health facility in the Kebele, and 415 (63.8%) had to travel more than 5km from home to the health facility (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health facility factors of the study participants among postpartum mothers in the South Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | frequency | percent% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health facility in your Kebele | Yes No | 563 87 |

86.6 13.4 |

| Public transport service in your area to visit the health facility | Yes No |

521 129 |

80.2 19.8 |

| The distance from home to health institution | <5 km ≥5 km |

235 415 |

36.2 63.8 |

| Referred from other health facilities | Yes No |

205 445 |

31.5 68.5 |

| Mode of transportation | Foot Ambulance private care |

411 223 16 |

63.2 34.3 2.5 |

3.1. Factors of delay in making a decision to seek care on institutional delivery

We performed bivariate analysis to assess any relationship between independent variables and delay in seeking care on institutional delivery. In bivariate analysis, residence, education status of the mothers, occupation status of the mothers, ANC visit, planning of pregnancy, number of children, time of labor onset, the distance from home to health institution, and the health facility in the Kebele were considered statistically significant with delay in deciding against seeking care on institutional delivery. In the multivariable logistic regression, residing in a rural area were 3.14 times more likely to delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery than those living in urban (AOR: 3.14,95%, CI: 2.40–4.01). Uneducated postpartum mothers were 3.62 times more likely to delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery than educated mothers (AOR: 3.62, 95%, CI: 2.45–5.52), Respondents with unplanned pregnancy were 2.01 times more likely to delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery than those who had planned pregnancy (AOR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.84–7.96), and those who had no health facilities in Kebele were 1.62 times more likely delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery than who had health facilities in Kebele (AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.43–6.32) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery among postpartum mothers in the South Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Delay in making decision to seek care |

COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories Delayed | No delayed | ||||

| Residence | Urban Rural |

61 251 |

163 175 |

1 3.83 (3.19–7.82) |

1 3.14 (2.40–4.01) ∗∗ |

| Education status of the mothers | Educated Uneducated | 192 147 |

267 44 |

1 4.65 (3.79–8.56) |

1 3.62(2.45-5.52) ∗∗ |

| Occupation status of the mothers | Employed Unemployed | 104 132 |

232 182 |

1 1.62 (1.09–2.59) |

|

| ANC visit | 100 136 |

272 142 |

1 2.61 (1.54–4.39) |

||

| Planned of pregnancy | Yes No | 220 54 |

172 13 |

1 3.24 (1.72–6.14) |

1 2.07(1.84-7.96) ∗ |

| Number of children | one 2-4 children ≥5 children |

127 94 15 |

201 174 39 |

1 0.86 (0.23–0.96) 0.61 (0.53–0.81) |

|

| Time of labor onset | Day Night |

152 174 |

240 84 |

1 3.27 (1.65–3.56) |

|

| The distance from home to health institution | <5km ≥5km |

79 157 |

156258 | 1 1.20 (1.02–8.28) |

|

| The health facility in the Kebele | Yes No |

13 223 |

74 340 |

1 8.68 (2.68–10.65) |

1 1.62(1.43-6.32) ∗ |

1 = reference ∗ = p-value < 0.05, and ∗∗ = p-value ≤ 0.001.

4. Discussion

In this study, the proportion of delay in deciding for seeking care on institutional delivery among the south Gondar zone hospitals was 36.3% (32.6–40.1). More than one in three postpartum mothers had been delayed in deciding to seek care in the South Gondar zone hospitals. Mothers residing in rural areas, uneducated mothers, unplanned pregnancies, and no health facilities in Kebele were statistically associated variables with delay in making decisions.

The finding of this study was consistent with a study conducted in the Hadiya zone (40.1%) [9]. However, delay in deciding to seek emergency obstetric care on institutional delivery service was lower than that reported in another study conducted in Dawuro zone, 42%, [3]. The possible explanation might be the difference in the socio-cultural characteristics of the study participants [6]. On the other hand, the current study finding was higher than that reported in the study conducted in the Arsi zone [10]and North Showa [20], where 26.2% and 23.1% cases were reported. The possible reason might be a lack of awareness among mothers related to information exposure of the family as a whole for danger signs of pregnancy [21]. Among the study population, 29.4% of the mothers and 21.5% of husbands could not read and write. In addition to this, in the current study, 34.5% of informants were rural residents living in poor socioeconomic status. It may affect their delivery service utilization and can contribute to the proportion being high. Lastly, it might be due to the lack of skilled healthcare providers and a disrespectful service delivery system.

The current study demonstrated that rural residency was a statistically significant factor with the outcome variable. Those mothers living in a rural area were more than three times more likely to delay in deciding to seek care for institutional delivery than those living in the Urban. This finding is supported by studies conducted in the Dawuro zone [3]. The possible reason might be the lack of women empowerment for early decision-making autonomy, poor physical access to health facilities that provide safe delivery service, poor road construction, and lack of access to health education regarding complications during labor and delivery [11,22]. Our previous study shows that only 35.1 % of the participants use an ambulance to access healthcare facilities during emergency obstetric care [23]. On the other hand, cultural norms more commonly influence rural women and prevent utilizing maternal healthcare services. On the contrary, urban women are more aware of the benefits of health facility delivery through different media [24]. Thus, they are less likely to delay in making a decision on emergency obstetric care for institutional delivery.

The uneducated mothers were more than 3.62 times more likely to be delayed in deciding to seek care on institutional care services than their counterparts [24, 25, 26]. Non-educated women may be less likely to attend antenatal visits and are unable to make informed decisions about seeking medical attention in the event of a birth emergency. They are also more likely to be influenced by traditional beliefs and customs, as well as vulnerable to labor and delivery issues as a result of institutional delivery delays [24,27]. It aids in breaking down some of the taboos and other traditional customs that prevent people from using health care facilities.

The result of this study revealed that mothers who had unplanned pregnancies were 2.07 times more likely delayed in making a decision to seek care on institutional care services. It demonstrates that unplanned pregnancies can result in a variety of health risks for both the mother and child, including malnutrition, illness, abuse and neglect, and even death.

Lastly, the study also suggested that mothers who had no access to health facilities were 1.62 times more likely to delay in deciding to seek care on institutional delivery than those with a health facility. Pregnant mothers who live close to health-care facilities may have better access to maternal health services such as maternal health education [28]. Furthermore, mothers had easy access to transportation to attend their deliveries at health facilities at any time, regardless of when their labor began.

5. Conclusion

The proportion of delay in making a decision was high in the South Gondar Zone. The proportion was 36.3% among postpartum mothers. Mothers living in rural areas, unplanned pregnancies, uneducated mothers, and no health facilities in Kebele were associated factors with delays in making decisions. Therefore, stakeholders must address them to reduce the proportion of delay in deciding to receive on-time care. We advocate for greater emphasis on mothers living in rural areas, mothers who do not have planned pregnancies, uneducated women, and making health care facilities available to pregnant women. As a result, the proportion of decision-making delays in the South Gondar Zone will be reduced to an acceptable level.

6. Strengths

The probability sampling technique was considered the strength of this study to generalize the findings to the study population. Conducting analyses using the logistic regression model was considered the strength of this study because it shows the association between predicted and response variables. We selected an appropriate model to control the effect of confounders to minimize the introducing bias at the analysis stage.

7. Limitation

It was preferable to conduct this research in a community setting where it was observed. In these cases, mothers in the community may be overlooked, and the proportion of decision-making delays may be greater than the current finding. As a result, this finding only applied to postpartum mothers who gave birth at a health care facility.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Gebrehiwot Ayalew Tiruneh and Dawit Tiruneh Arega Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Bekalu Getnet Kassa: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Keralem Anteneh Bishaw: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the University of Gondar, who gave us the opportunity and the Amhara region health office to provide a supportive letter. Our appreciation went to the study participants, data collectors, and supervisors for their permission to participate and spending precious time for us.

References

- 1.Roy M.P. Factors determining institutional delivery in rural India. Med. J. Dr. DY Patil Vidyapeeth. 2020;13(1):53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarinbab T.E., Balcha S.G. 2018. Delays in Utilization of Institutional Delivery Service and its Determinants in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia: Health Institution Based Cross Sectional Study. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodicho T. 2020. Delay in Making Decision to Seek Institutional Delivery Service Utilization and Associated Factors Among Mothers Attending Public Health Facilities in Dawuro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berhan Z., et al. Prevalence of HIV and associated factors among infants born to HIV positive women in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mgawadere F., et al. Factors associated with maternal mortality in Malawi: application of the three delays model. BMC Preg. Childbirth. 2017;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geleto Ayele, Chojenta Catherine, Abdulbasit Musa, Loxton Deborah. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of literature. BMC (Biomed. Chromatogr.) 2018 doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0842-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asare, E.A.M., Determinants Of Utilisation Of Maternal Health Care Services Among Pregnant Women In Kwahu South District. 2017, University Of Ghana.

- 8.Gabrysch S., Campbell O.M. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Preg. Childbirth. 2009;9(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lire A., et al. Delays for utilizing institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers attending public health facility in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Science. 2017;5(6):149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amare Y.W., et al. Factors associated with maternal delays in utilising emergency obstetric care in Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. S. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;25(2):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jha N.K. 2012. Factors Associated with First Delays to Seek Emergnancy Obstetric Care Service Among the Mother of Matsarie VDC of Rautahat District. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildah Essendi S.M., Fotso Jean-Christophe. Barriers to formal emergency obstetric care services’ utilization. J. Urban Health: Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2010;88 doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9481-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berhan Y., Berhan A. Commentary: reasons for persistently high maternal and perinatal mortalities in Ethiopia: part III–perspective of the “three delays” model. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2014;24:137–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killewo J., et al. Perceived delay in healthcare-seeking for episodes of serious illness and its implications for safe motherhood interventions in rural Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2006;24(4):403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thaddeus S., Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994;38(8):1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathak P., et al. Factors associated with the utilization of institutional delivery service among mothers. J. Nepal Health Res. Council. 2017;15(3):228–234. doi: 10.3126/jnhrc.v15i3.18845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andargie A.A., Abebe M. Factors associated with utilization of institutional delivery care and postnatal care services in Ethiopia. J. Publ. Health Epidemiol. 2018;10(4):108–122. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Win T., Vapattanawong P., Vong-ek P. Three delays related to maternal mortality in Myanmar: a case study from maternal death review, 2013. J. Health Res. 2015;29(3):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarinbab T.E., Balcha S.G. Delays in utilization of institutional delivery service and its determinants in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia: health institution based cross-sectional study. J. Gynecol. Women’s Health. 2018;10(3):555793. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abera G., et al. Male partner role on reducing delay in decision to seek emergency obstetric care and associated factors among women admitted to maternity ward, in hospitals of North Showa, Amhara, Ethiopia. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Echoka1 Elizabeth, Makokha2 Anselimo, Dubourg3 Dominique, Kombe1 Yeri, Nyandieka1 Lillian, Byskov4 Jens. 2014. Barriers to Emergency Obstetric Care Services: Accounts of Survivors of Life Threatening Obstetric Complications in Malindi District, Kenya. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaisera Jeanette L., Fonga Rachel M., Davidson H., Hamera B., Biembac Godfrey, Ngomac Thandiwe, Tusinga Brittany, Scotta Nancy A. Social Science & Medicine; 2018. How a Woman's Interpersonal Relationships Can Delay Care-Seeking and Access during the Maternity Period in Rural Zambia: an Intersection of the Social Ecological Model with the Three Delays Framework. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayalew Tiruneh G., et al. Delays during emergency obstetric care and their determinants among mothers who gave birth in South Gondar zone hospitals, Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study design. Glob. Health Action. 2021;14(1):1953242. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1953242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Broek N. 2015. Prevalence and Predictors of Institutional Delivery Among Pregnant Mothers in Biharamulo District, Tanzania: a Cross-Sectional Study. Kihulya Mageda1,&, Elia John Mmbaga2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tesfaye Gezahegn, Loxton Deborah, C C., Smith A.S.a.R. 2017. Delayed initiation of antenatal care and associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. reproductive healthj. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teklehaymanot1 A.K.K.H. Alemi Kebede1 Kalkidan Hassen2 Aderajew Nigussie Teklehaymanot1; 2016. Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Service Utilization in ethiopia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teklemariam Gultie∗ B.W. Mekdes kondale and besufekad Balcha, Home Delivery and Associated Factors among Reproductive Age Women in Shashemene Town, Ethiopia. Journal of Womens Health Care. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asrat A.A., Mengistu A. Factors associated with utilization of institutional delivery care and postnatal care services in Ethiopia. J. Publ. Health Epidemiol. 2018;10(4):108–122. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.