Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapy has been shown to be an effective strategy for combatting non-solid tumors; however, CAR-T therapy is still a challenge for solid tumors, such as glioblastoma. To improve CAR-T therapy for glioblastoma, a new TanCAR, comprising the tandem arrangement of IL13 (4MS) and EphA2 scFv, was generated and validated in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, the novel TanCAR-redirected T cells killed glioblastoma tumor cells by recognizing either IL-13 receptor α2 (IL13Rα2) or EphA2 alone or together upon simultaneous encounter of both targets, but did not kill normal cells bearing only the IL13Rα1/IL4Rα receptor. As further proof of principle, the novel TanCAR was tested in a subcutaneous glioma xenograft mouse model. The results indicated that the novel TanCAR-redirected T cells produced greater glioma tumor regression than single CAR-T cells. Thus, the novel TanCAR-redirected T cells kill gliomas more efficiently and selectively than a single IL13 CAR or EphA2 scFv CAR, with the potential for preventing antigen escape and reduced off-target cytotoxicity.

Keywords: glioblastoma, CAR, TanCAR, IL13, EphA2, CAR-T

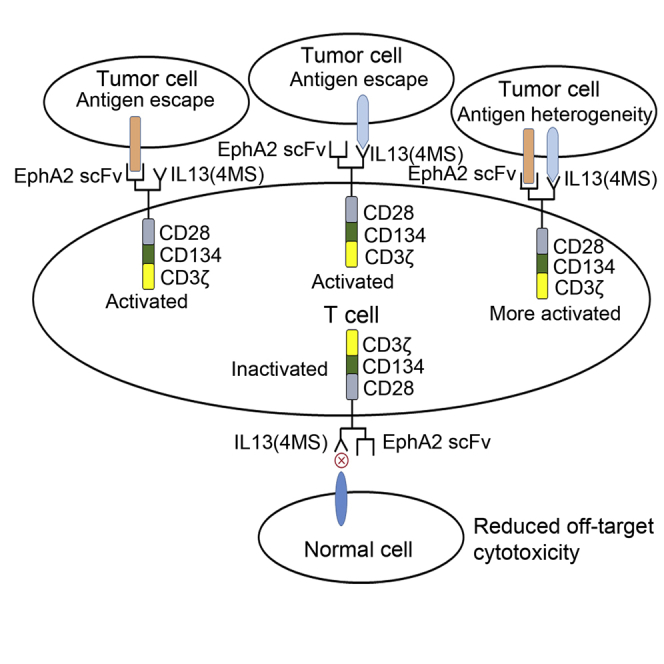

Graphical abstract

A novel, bispecific TanCAR targeting IL13Rα2 and EphA2 developed in the study could perform significantly superior antitumor activity both in vitro and in vivo than their single-specificity CAR counterpart, which would have great potential to reduce the off-target toxicity and to mitigate antigen escape in glioblastoma therapy.

Introduction

Glioblastoma, a grade IV tumor, is the most common type of primary brain tumor. Despite intensive conventional treatments, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, the average survival time is no longer than 14 months. The most common reason for the short survival time is tumor recurrence after conventional treatment owing to incomplete removal of the tumor and infiltrating tumor cells.1,2 Therefore, new therapies are needed to treat glioblastoma and to improve the survival and quality of life of glioblastoma patients.

Over the last few years, chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T cell) therapy has emerged as a promising cancer treatment, with approval from the US Food and Drug Administration as an investigational therapy for B-cell malignancies.3 Yet, the success rates of CAR-T cell therapies for solid tumors, especially glioblastoma, are much lower than those for B-cell malignancies owing to various challenges; these challenges are actively being addressed to make CAR-T cell therapy successful against solid tumors.3 CAR-T cell therapy for glioblastoma is based on several antigens, including interleukin 13 receptor α2 (IL13Rα2),4 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2),5 epidermal growth factor variant III (EGFRvIII),6 and erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular carcinoma A2 (EphA2).7 Of these, IL13Rα2 is the most suitable target for glioblastoma, as it is overexpressed in approximately 50%–80% of gliomas, while its expression is undetectable in the normal brain.8,9 Moreover, IL13Rα2 is a decoy receptor for IL13 in glioma cells because its binding affinity for IL13 is higher than that for the ubiquitously expressed IL13Rα1.10 However, in normal cells, IL13 can bind to the shared and physiologically abundant IL13Rα1/IL4Rα.11,12 Studies have shown that a single substitution at E13K or E13Y in the α-helix and at K105R or R109K in the D-helix of IL13 enhances its selectivity for recognizing IL13Rα2.13, 14, 15 Although IL13 with substitutions at both E13K and R109K has been reported to further improve the selectivity for recognizing IL13Rα2,4 IL13 with E13K and R109K mutations still retains its ability to recognize IL13Rα1.4,16 Interestingly, a few studies have shown that substitutions at R66D and S69D in the C-helix of IL13 allowed IL13 to retain its selectivity for recognizing IL13Rα2, but not for shared IL13Rα1/IL4Rα.17,18 Thus, to further improve the specificity and activity of IL13, a novel IL13 CAR is needed. EphA2 is overexpressed in glioblastoma,19,20 is not associated with the development of antigen loss variants like EGFRvIII,7 and is suggested to be a safe target for CAR therapy. Therefore, EphA2 is another suitable target for glioblastoma therapy.

Conventional CAR-T cell therapy may be less effective against solid tumors such as glioblastoma owing to tumor antigen heterogeneity and tumor antigen escape. A tandem CAR (TanCAR) is a CAR that is bispecific toward both antigens, with a single exodomain that distinctly recognizes each target molecule; TanCAR function can be enhanced when both target antigens are encountered simultaneously.21 A TanCAR consisting of IL13 (E13K.R109K) and a HER2 single chain variable fragment (scFv) toward both IL13Rα2 and HER2 has been used in glioblastoma therapy to overcome tumor antigen heterogeneity and antigen escape.22 However, IL13 (E13K.R109K)- and HER2 scFv-based CAR-T cells can harm normal cells by off-target recognition of IL13Rα1 and HER2, which are also expressed in normal cells.22,23 Thus, a novel TanCAR needs to be explored for glioblastoma therapy.

We developed a novel IL13 (E13K.R66D.S69D.R109K)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR targeting IL13Rα2 and EphA2, then validated its specificity and activity in vitro and in vivo. The results showed that the novel TanCAR has improved specificity and selectivity for IL13Rα2 and efficiently induced tumor regression, thus offering a new glioblastoma therapy strategy.

Results

Construction of a novel IL13 (4MS) CAR and the assay of its activity using a cell-based luciferase reporter system in vitro

To improve the selectivity of IL13 for IL13Rα2 and to greatly decrease its binding activity with IL13Rα1, a novel mutated IL13, named IL13 (4MS) with four amino acid mutations, was created by putting E13K, R66D, S69D, and R109K substitutions together in IL13—a strategy based on findings from previous studies.4,13, 14, 15, 16 Then, the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR was constructed based on the novel IL13 mutant.

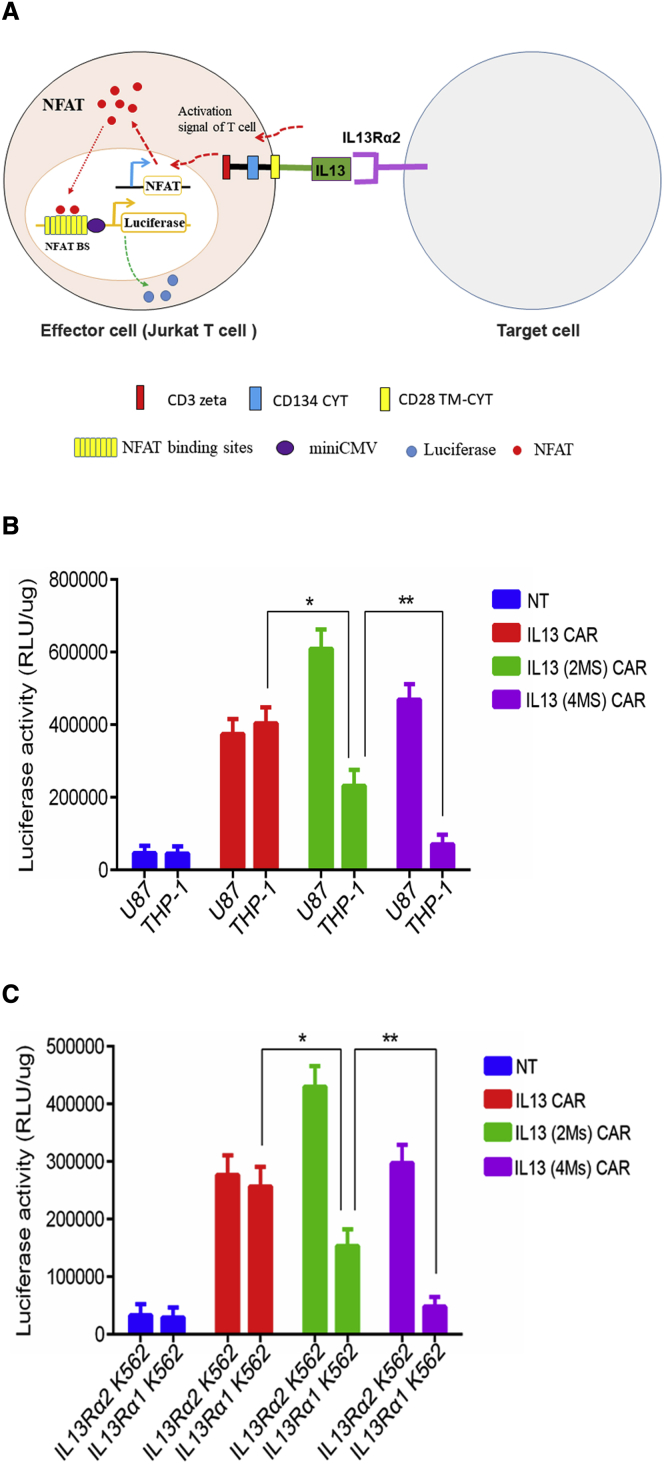

To evaluate the specificity and activity of the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR, a luciferase reporter-based system in Jurkat cells was established based on CAR activation (Figure 1A). The system includes two main components: (1) effector cells, Jurkat T cells which carry a nuclear factor of activated T cell (NFAT)-driven luciferase reporter and a CAR, and (2) target cells that carry a molecule interacting with the CAR. When the CAR on the surface of the Jurkat cells was activated by its partner, the luciferase activity in the Jurkat cells increased (Figure 1A). The expression of EphA2, IL13Rα1, or IL13Rα2 on the surface of U87 cell line or THP-1 cell line was detected by quantitative PCR (Figure S1), which was consistent with the results reported by.4,7,16,24, 25, 26, 27 Then, three types of Jurkat IL13 CAR-T cells carrying the NFAT-driven luciferase reporter expressing the IL13 CAR, IL13 (2MS) CAR carrying two amino acid mutations (E13K and R109K), or the IL13 (4MS) CAR were co-cultured with IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cells or IL13Rα1+α2− THP-1 cells. The results indicated that the IL13 Jurkat CAR-T cells showed no significant difference in luciferase activity in either the IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cell line or the IL13Ra1+α2− THP-1 cell line (Figure 1B), which means that wild-type IL13 mainly recognizes the IL13Rα1 that is abundantly expressed in normal cells. IL13 (2MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells showed significantly higher luciferase activity than the IL13 Jurkat CAR-T cells when incubated with IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cells, but significantly lower luciferase activity than the IL13 Jurkat CAR-T cells when incubated with IL13Rα1+α2− THP-1 cells (Figure 1B), suggesting that IL13 (2MS) had improved binding activity to IL13Rα2 compared with wild-type IL13. As we had hypothesized, the novel IL13 (4MS) lost its ability to bind to IL13Rα1+ cells without any loss of its binding ability to IL13Rα2+ cells based on the assay of luciferase activity in IL13 (2MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells or IL13 (4MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells (Figure 1B). The above results are from an independent experiment performed in triplicate; similar results were obtained from two other independent experiments performed in triplicate (Figures S2 and S3). In addition, to further test the biological activity of the IL13 (4MS) CAR, IL13Rα1-and IL13Rα2-engineered K562 cell lines were generated. Similar results were obtained with these two target cell lines as those obtained with the IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cell line and the IL13R1α +α2− THP-1 cell line (Figure 1C). The results above indicated that the IL13 (4MS) CAR could be selectively activated by IL13Rα2.

Figure 1.

Functional characterization of the novel IL13 CAR in Jurkat T cells

(A) Illustration of a cell-based luciferase reporter system for analyzing the biological activity of IL13 CAR. When a CAR expressed on the surface of Jurkat T cells (named the effector cell) carrying a luciferase reporter driven by an NFAT-response element was activated by its partner molecule present on the target cell, the luciferase expression level increased. (B) The biological activity assay of different CARs with U87 or THP-1 target cells using a cell-based luciferase reporter system. (C) The biological activity assay of different CARs with IL13Rα2-or IL13Rα1-engineered K562 target cells using a cell-based luciferase reporter system. Shown are representative plots of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistically significant differences are indicated: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. IL13 (2MS) stands for IL13 (E13K.R109K), while IL13 (4MS) stands for IL13 (E13K.R66D.S69D.R109K).

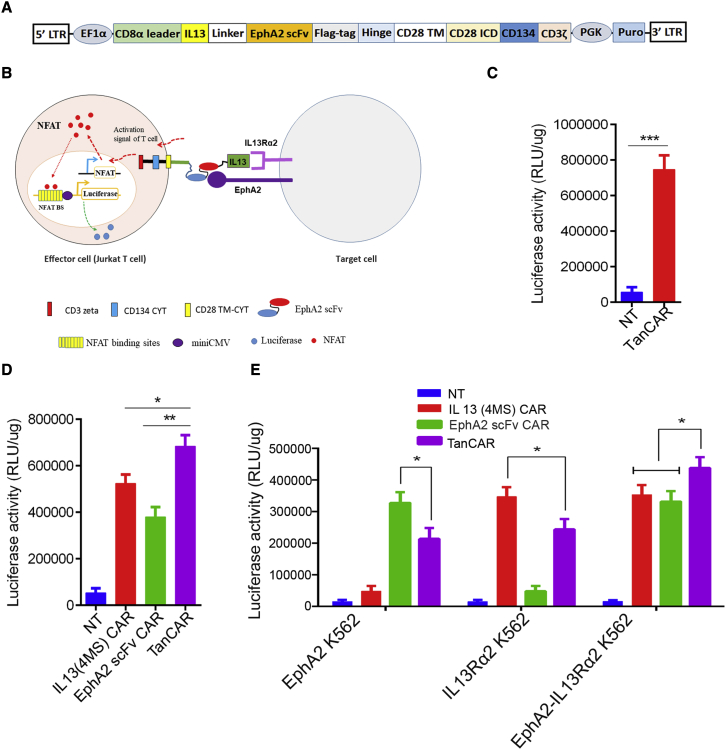

Construction of a novel TanCAR targeting IL13 and EphA2 and the assay of its activity in vitro

Unlike other solid tumors, glioblastoma is heterogeneous in nature and is also notorious for antigen escape.28 A TanCAR-T cell strategy is the most suitable for killing heterogeneous gliomas, as well as for mitigating antigen escape in glioblastoma therapy.21,22 To selectively kill gliomas and overcome antigen escape in glioblastoma CAR-T cell therapy, a novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR toward both IL13Rα2 and EphA2 was constructed by tandem-inserting IL13 (4MS) and EphA2 scFv with a (GGGS)3 linker between them into a third-generation CAR backbone (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Functional characterization of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR in Jurkat T cells

(A) Cartoon of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR. To construct this novel TanCAR, IL13 (4MS) was inserted into a third-generation CAR backbone, then EphA2 scFv was linked with IL13 (4MS) by a (GGGS)3 linker. (B) Illustration of a cell-based luciferase reporter system for analyzing the biological activity of the novel TanCAR. (C) The biological activity assay of IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR with U87 cells using a cell-based luciferase reporter system. (D) The biological activity assay of IL13 (4MS) CAR, EphA2 scFv CAR or IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR with U87 cells using a cell-based luciferase reporter system. (E) The biological activity assay of IL13 (4MS) CAR, EphA2 scFv CAR, or IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR with EphA2-engineered K562 target cells, IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells, or EphA2-IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells individually using a cell-based luciferase reporter system. Shown are representative plots of at three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistically significant differences are indicated: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. TanCAR stands for IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR.

Then, to evaluate the functionality of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR toward IL13Rα2 and EphA2, IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR Jurkat T cells were obtained by infecting Jurkat cells with lentivirus expressing the TanCAR. Then, the novel TanCAR was assayed using a similar cell-based luciferase reporter system as described above (Figure 2B). When IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR Jurkat T cells were co-cultured individually with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells, the IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR Jurkat T cells showed significantly higher luciferase activity with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells than with non-transduced (NT) Jurkat T cells (Figure 2C). This luciferase activity provided the initial evidence that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR was functional with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells. Then, we compared the luciferase activity of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv Jurkat TanCAR-T cells with that of single IL13 (4MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells or single EphA2 scFv Jurkat CAR-T cells by co-culturing with EphA2+ or IL13Rα2+ U87 cells. The results indicated that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv Jurkat TanCAR-T cells showed significantly higher luciferase activity than single IL13 (4MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells or single EphA2 scFv Jurkat CAR-T cells (Figure 2D). In addition, we also tested whether the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR could distinctly recognize either IL13Rα2 or EphA2 alone, as well as both together upon simultaneous encounter. For this purpose, the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv Jurkat TanCAR-T cells were co-cultured with EphA2-engineered K562 target cells, IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells, or EphA2-IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells. The results indicated that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv Jurkat TanCAR-T cells showed significant luciferase activity with the EphA2-engineered K562 target cells, the IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells, or the EphA2-IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells compared with the NT Jurkat control group. However, interestingly, the luciferase activity in the TanCAR co-cultured with the IL13Rα2-EphA2-engineered K562 target cells group was significantly higher than that in the groups of TanCAR co-cultured with IL13Rα2-engineered K562 target cells or the EphA2-engineered K562 target cells (Figure 2E). This finding indicated that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR could recognize each target alone or both together upon simultaneously encountering both targets, suggesting that this novel TanCAR could potentially offset antigen escape.

However, we found that the luciferase activity in the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv Jurkat TanCAR-T cells was lower than that in single IL13 (4MS) Jurkat CAR-T cells or single EphA2 scFv Jurkat CAR-T cells when they are co-cultured with EphA2-engineered or IL13Rα2- K562 target cells expressing a single target molecule (Figure 2E). The results indicated that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR has a reduced ability to recognize the individual targeted in comparison with that monospecific IL13 (4MS) Jurkat CAR or single EphA2 scFv Jurkat CAR. The above results are from an independent experiment performed in triplicate, and similar results were obtained from two other independent experiments performed in triplicate (Figures S4 and S5).

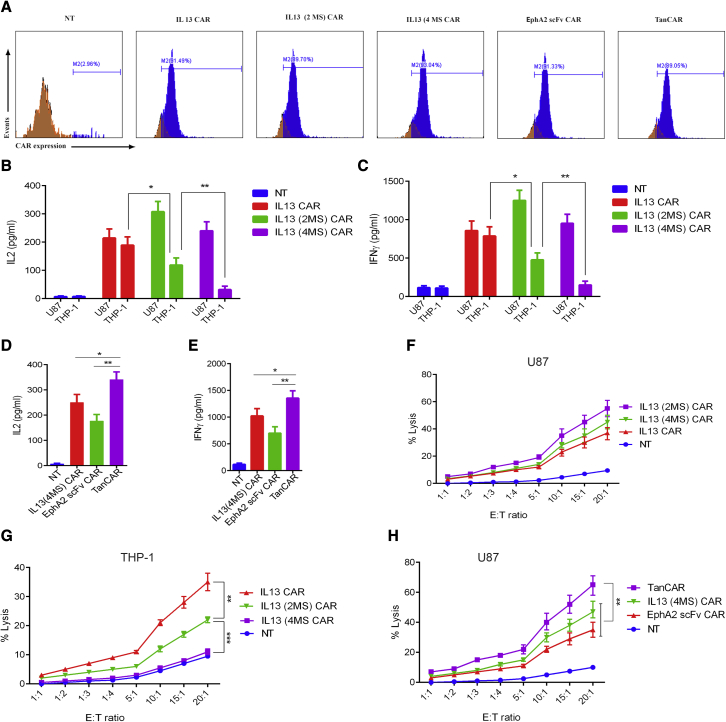

After preliminarily testing all types of CARs in Jurkat T cells, we characterized both the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR and the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR in human primary CD8+ T cells. For this purpose, single IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, and IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells were obtained by infecting CD3/CD28-activated human primary CD8+ T cells with three types of lentivirus, separately. Two to 4 days after the third infection, flow cytometry using anti-Flag antibody was performed three times to quantify the expression of CAR on the surface of human primary CD8+ T cells. The expression of IL13 CAR was 89%, 91%, and 92%. The expression of IL13 (2MS) CAR was 87%, 89%, and 91%. The expression of IL13 (4MS) CAR was 92%, 93%, and 94%. The expression of EphA2 CAR was 87%, 89%, and 91%. The expression of TanCAR was 88%, 89%, and 91%. The representative results of three experiments are shown in (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Functional characterization of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR in human primary CD8+ T cells

(A) The detection of the CAR expression level on the surface of human primary CD8+ T cells by flow cytometric assay with anti-Flag antibody. (B) The detection of IL2 levels in the supernatants from different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells co-cultured with U87 cells or THP-1 cells. (C) The detection of IFNγ levels in the supernatants from different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells co-cultured with U87 cells or THP-1 cells. (D) The detection of IL2 levels in the supernatants from different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells co-cultured with U87 cells. (E) The detection of IFNγ levels in the supernatants from different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells co-cultured with U87 cells. (F) The measurement of the cytotoxic activity of different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells for U87 cells by LDH level assay. (G and H) The measurement of the cytotoxic activity of different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells for THP-1 cells by LDH level assay (H) The measurement of the cytotoxic activity of different groups of CD8+ CAR-T cells for U87 cells by LDH level assay. Shown are representative plots of three experiments performed in triplicate. Statistically significant differences are indicated: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01. TanCAR stands for IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR.

Then, the levels of interferon (IFN) γ and IL2 were detected in culture supernatants 24 h after co-culturing single IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, and EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, as well as IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells. Consistent with the result of luciferase activity in the study, the level of cytokines produced by IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells was lower than that by IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells or IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, which further confirmed that the novel redirected CD8+ T cells IL13 (4MS) CAR lost its ability to bind to IL13Rα1+ cells without any loss of its binding ability to IL13Rα2+ cells (Figures 3B and 3C). Whereas the results indicated that IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells produced significantly higher levels of cytokines compared with single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells or EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells (Figures 3D and 3E). These results suggested that the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR-redirected CD8+ T cells could be selectively activated by IL13Rα2, whereas the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR-redirected CD8+ T cells could be more efficiently activated than single IL13 (4MS) CAR- or EphA2 scFv CAR-redirected CD8+ T cells.

Next, to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR against IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cells and the IL13R1α +α2− THP-1 cells, we co-cultured IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, and IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells with the IL13Rα1+α2+ U87 cells or the IL13R1α +α2− THP-1 cells at effector to target (E:T) ratios of 20:1, 15:1 10:1, 5:1, 4:1, 3; 1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively. Similarly, to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the novel TanCAR against EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 glioma cells, we co-cultured single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells and EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, as well as IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells at E:T ratios of 20:1,15:1, 10:1, 5:1, 4; 1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively. Then, 24 h later, we assessed lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) secretion levels in the culture supernatants. The results indicated that IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells exhibited significant cytotoxicity against IL13Rα2+ cells, but did not exhibit any significant cytotoxicity against IL13Rα1+ cells (Figures 3F and 3G). Whereas, IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity against target cells than single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ or EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells (Figure 3H). The above results are from an independent experiment performed in triplicate; similar results were obtained from two other independent experiments performed in triplicate (Figures S6 and S7).

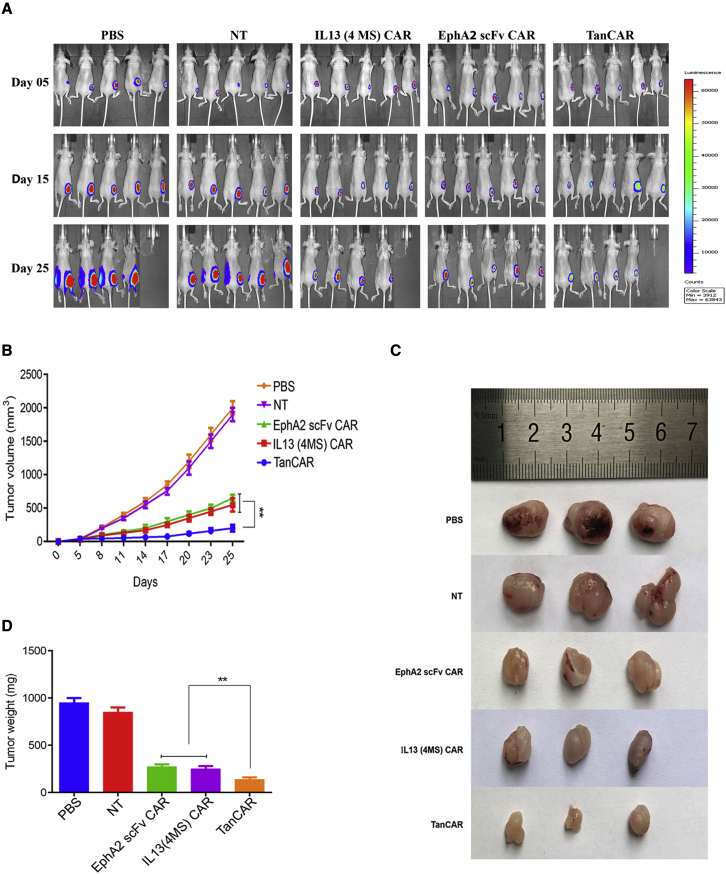

Assay of the antitumor activity of the TanCAR targeting IL13 and EphA2 in established glioblastoma xenografts

Having determined the antitumor activity of IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells in vitro, the principle of the novel TanCAR was further demonstrated in vivo using subcutaneous glioblastoma xenografts. The results of bioluminescence imaging and of measuring tumor volume every three days demonstrated that all three types of CAR-T cells could suppress established tumor growth (Figures 4A and 4B); however, the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells were the best at inhibiting tumor growth (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the antitumor activity of IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells in a glioblastoma animal model

(A) The detection of tumor progression by bioluminescence imaging. (B) The growth curve of tumors from the different groups treated with CAR-T cells. The tumor volume data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (mm3). (C) Photographs of tumors from different groups treated with CAR-T cells. On day 28 after tumor inoculation, tumors were resected immediately after euthanasia, and photographs of three samples from each group are shown. (D) Quantification of tumors from different groups treated with CAR-T cells by tumor weight. The tumor weight data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (mg). Statistically significant differences are indicated: ∗∗p < 0.01. TanCAR stands for IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR.

Representative photographs of the resected tumors were taken, and each resected tumor was weighed. These data supported the notion that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells had the most potent killing activity against tumor cells among the three types of CAR-T cells (Figures 4C and 4D).

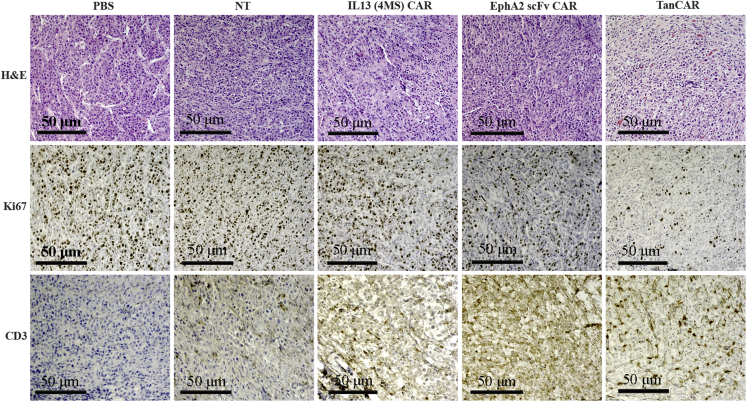

For immunohistochemical staining, we used mouse anti-Ki67 antibody to indicate the proliferated cells including tumor cells and some T cells, whereas, the stained cells by anti-human CD3 antibody specifically indicate the human CD3+ T cells. The staining results of anti-Ki67 antibody and anti-human CD3 antibody showed that tumor tissue samples from mice treated with the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells had low tumor cell proliferation and robust accumulation of human CD3+ T cells compared to tumor tissue samples from mice treated with single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells or EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells (Figure 5). These findings strongly suggested that TanCAR-based recognition can better induce T cell homing to tumor sites and can exert antitumor function. Collectively, these results demonstrated that the novel TanCAR-redirected T cells killed gliomas with high efficiency and selectivity, and with the potential for mitigating antigen escape and reducing off-target cytotoxicity.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the tumor cell proliferation and homing abilities of CAR-T cells by H&E and immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue samples

The immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples with anti-Ki67 and anti-human CD3 indicates the distribution of tumor cells and the human CD3+ T cells, respectively. TanCAR stands for IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR.

Discussion

Here, we described the generation of a novel IL13 (4MS) with improved selectivity for IL13Rα2 and diminished recognition of IL13Rα1, as well as its characterization in a third-generation CAR. Then, we developed a novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR that could more selectively kill heterogeneous gliomas and potentially overcome the antigen escape from CAR-T cell therapy in glioblastoma.

Increased expression of IL13Rα2 promotes tumor progression in glioblastoma and other tumors.9 In addition, IL13Rα2 not only inhibits the normal apoptosis mechanism induced by shared IL13Rα1/IL4Rα through STAT6, but also induces the upregulation of STAT3 and B-cell lymphoma 2 in glioma cells.29 Therefore, targeting IL13Rα2-expressing cells would not only decrease the tumor burden, but also alter the tumor microenvironment. IL13Rα2-targeted CAR-T cells have shown selective killing in vitro and regression of xenograft glioma tumors in animal models.27 Based on this success, several human clinical trials were also initiated with IL13Rα2 targeted-CAR-T cells. Subsequent tumor regression was observed in all clinical trials without observing any adverse event. However, a few patients were diagnosed with new metastases at different sites.30, 31, 32 EphA2-specific CAR-T cells could recognize EphA2-positive glioma cells and were potent for preventing neurosphere formation and destroying intact neurospheres in co-culture assays. Additionally, adoptive transfer of EphA2-specific CAR-T cells resulted in the regression of glioma xenografts in a mouse model.7 To date, no human clinical trial has been reported with EphA2-specific CAR-T cells; however, EphA2-specific CAR-T cells in patient are expected to be safe because EphA2 is expressed only in malignant cells, and not in normal cells.19

So far, two types of CARs targeting IL13Rα2 have been designed. One is an IL13Rα2 scFv CAR targeting IL13Rα2 by IL13Rα2 scFv (scFv47), and the other is an IL13 CAR targeting IL13Rα2 by its IL13. The IL13 CAR has some advantages over the IL13Rα2 scFv CAR because of the immunogenicity of the scFv and the competing binding of physically existing IL13 to IL13Rα2.33 The scFv47 works well only with a short spacer region; therefore, its arrangement in a CAR, and especially in a TanCAR, is contestable.24 Moreover, two scFvs are not appropriate for a TanCAR, because they can aggregate with one another: such a TanCAR can lead to CD3ζ domain phosphorylation, tonic T cell activation, and T cell exhaustion.34 Thus, an IL13 CAR targeting IL13Rα2 by its IL13 is preferable to an IL13Rα2 scFv CAR targeting IL13Rα2 by an IL13Rα2 scFv.

IL13 has two receptors: IL13Rα2 and IL13Rα1. Although the strong binding affinity of IL13 to IL13Rα2 in glioma cells is higher than that of ubiquitously expressed IL13Rα1, IL13 can also bind to the physiologically abundant IL13Rα1/IL4Rα complex present on the surface of normal cells.11,12 Previous studies have demonstrated that E13K and R109K substitutions together in IL13 could further improve the selectivity for the recognition of IL13Rα2.4 However, studies have also shown that IL13 with substitutions at E13K and R109K retained its ability to recognize IL13Rα1.4,16 In addition, the C-helix of IL13 is also involved in interactions with the shared IL13Rα1/IL4Rα receptor, and substitutions at R66D and S69D in the C-helix also increase the ability of IL13 to interact with IL13Rα2 and decrease its ability to interact with shared IL13Rα1/IL4Rα.17 Using this information, in this study, we created for the first time a novel IL13 (4MS) by putting R66D and S69D mutations together with E13K and R109K mutations in IL13 to further improve its selectivity for IL13Rα2 by diminishing IL13Rα1 recognition. However, mutations R66D and S69D targeting the C-helix residues can lead to a remarkable decrease in mutant IL13 activity.17 But interestingly, the IL13 (4MS) CAR with four mutations of E13K, R66D, S69D, and R109K in wild-type IL13 could be activated by IL13Rα2, but not by IL13Rα1, which, therefore, could markedly decrease its side effects owing to the abundant expression of IL13Rα1 in normal cells.

Conventional CAR-T cell therapy might be less effective for glioblastoma because this cancer shows substantial intercellular heterogeneity in the surface expression of glioma antigens and is also notorious for antigen escape.8,28 Together, these major challenges negatively impact CAR-T cell therapy for glioblastoma. A successful strategy for overcoming antigen escape in glioblastoma and in other cancers is the use of a TanCAR. Grada et al21 reported for the first time a single-chain bispecific CAR targeting CD19 and HER2. This TanCAR efficiently triggered T cell activation in response to CD19 or HER2. CD19 has proved itself an ideal target owing to the expression of CD19 in almost all B cell malignancies.35 CD19 CAR-T cell therapy has been considered a promising treatment for B cell malignancies.3 However, relapse after CAR T cell therapy remains a challenge owing to CD19 antigen escape. Results of the both preclinical and clinical trials of TanCAR targeting CD19 and CD20 may overcome the limitation of CD19-negative relapse.36, 37, 38, 39, 40 In addition, TanCAR targeting CD19 and CD20 has demonstrated potent clinical efficacy and low toxicity both in vivo and in vitro.41 TanCAR targeting IL13Rα2 and HER2 has been tested in preclinical model to overcome tumor antigen heterogeneity and antigen escape in glioblastoma therapy.22 TanCAR targeting CD70 and B7-H3 has demonstrated a potent preclinical activity against multiple solid tumors and melanoma.42 Therefore, in this study, we developed for the first time a novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR by tandemly arranging novel IL13 (4MS) and EphA2 scFv toward both IL13Rα2 and EphA2 molecules. We chose IL13 (4MS) for our novel TanCAR because in the first part of this study, we showed that IL13 (4MS) CAR with four mutations (4MS) in wild-type IL13 could be activated by IL13Rα2, but not by IL13Rα1, and we also showed that the CAR was more effective than the IL13 CAR in vitro. EphA2 scFv was chosen as a second antigen recognition domain for our novel TanCAR because EphA2 is overexpressed in glioma, where it promotes its malignant phenotype. EphA2 is not associated with the development of antigen loss like EGFRvIII.7 In addition, EphA2 scFv CAR-T cells can prevent the formation of neurospheres.7 Another study has also demonstrated that a bivalent combination of EphA2 and IL13Rα2 had superior antitumor effects against glioblastoma than any other bivalent combination.22

The primary purpose of a TanCAR for glioblastoma is killing the heterogeneous gliomas and mitigating antigen escape in glioblastoma therapy.22 We found that the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR was able to recognize IL13Rα2 and EphA2 distinctly and effectively and has superior sustained activity when both targets are encountered. Thus, the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR can kill heterogeneous glioblastoma more selectively with fewer chances of antigen escape.

The persistence of CAR T cells at the tumor site after infusion is also a challenge, but one being improved by using different approaches.3 In this study, we found that the accumulation of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR-redirected T cells at the tumor site was higher than that of the single IL13 (4MS)-CAR- or EphA2 scFv CAR-redirected T cells. This increased accumulation might be due to an improved persistence rate of the TanCAR.43 Thus, TanCAR-based recognition can enhance the persistence of CAR T cells at the tumor site.

Our data align with the results of Hegde et al,22 who for the first time showed that novel TanCAR-T cells performed significantly better in terms of antitumor activity than their single-specificity CAR counterparts in glioblastoma therapy. However, a central concern for CAR-T cell therapy is the specificity of the target antigen for tumorous versus normal expression of the antigen on vital organs like the heart, liver, and lungs. Nonspecific CAR-T cell therapy can kill normal cells by off-target recognition. The potency and accompanying hazard potential of CAR-T cell therapy were clearly shown by the toxic death of the first patient treated with CAR-T cells against HER2: the death was caused by the off-target recognition of HER2 in vital organs, including the lung, bowel, and heart.23,44 In addition, off-target recognition also increases the chances of several toxicities, including cytokine release syndrome23—the most common adverse event, which can range from mild to life threatening.45,46 Moreover, a nonspecific TanCAR can increase the risk of killing normal cells and can increase toxicities owing to off-target recognition of both targets, making it unsuitable for clinical application. Our novel IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR-redirected T cells showed highly selectivity for IL13Rα2 and EphA2, thus greatly reducing off-target toxicity and making it very suitable for glioblastoma treatment.

Hematological malignancies have been treated successfully by CAR-T cell therapy. However, CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors, especially for glioblastoma, remains a serious challenge in the field owing to physical barriers and an immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment. We constructed a novel TanCAR that has better antitumor activity than its single-specificity CAR counterparts. In addition, the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR has the potential to reduce cytotoxicity caused by off-target effects, as well as the potential to mitigate tumor antigen escape. This work offers a new CAR-T cell therapeutic strategy for successfully treating patients with glioblastoma.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

U87, a human glioma cell line; HEK293T, a human embryonic kidney cell line; K562, a human erythroleukemic cell line; THP-1, a human myeloid leukemia mononuclear cell line; and Jurkat, a human T cell lymphoblast-like cell line, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. U87 and HEK293T cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and 2 mM GlutaMAX-I at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The THP-1, K562, and Jurkat T cell lines were grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% FCS containing 2 mmol/LGlutaMAX-I at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. In addition, U87 cells stably expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein and firefly luciferase (U87.eGFP.FFLuc) were generated by lentiviral transduction. Similarly, the K562 target cell line was also engineered individually to stably express IL13Rα1, IL13Rα2, and EphA2 molecules or both IL13Rα2 and EphA2 molecules together on the surface of K562 target cells.

Creation of a novel IL13

A human IL13 gene encoding the mature peptide was amplified by PCR using the paired primers, then the PCR products were purified and ligated with pGEMT-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The positive clone was confirmed by sequencing and called pGEMT-hIL13-mature. To obtain the mutated forms of mature IL13 from wild-type IL13, mutagenic primers from Tsingke Biological Technology (Xi'an, Shaanxi, China) were synthesized and named. The E13K mutation of mature IL13 was obtained using the E13K primer pair based on the wild-type IL13 template. Then, the E13K.R109K mutation of mature IL13 was obtained using the R109K primer pair based on the IL13 (E13K) template. The obtained IL13 with two amino acid mutations was named IL13 (2MS). Using a similar strategy, the IL13 (E13K.R66D.S69D.R109K) named IL13 (4MS) was obtained using the R66D and S69D primer pairs. The sequences of IL13 (2MS) and IL13 (4MS) were confirmed by Tsingke Biological Technology. All primer pairs are shown in Table S1.

Generation of CAR constructs

A third-generation CAR backbone was synthesized by Tsingke Biological Technology; the backbone contained a human CD8a leader sequence and a FLAG tag for detecting CAR expression, followed by CD28 transmembrane and costimulatory domains derived from CD28, CD134, and CD3ζ.47, 48, 49, 50 The three types of IL13—IL13, IL13 (2MS), and IL13 (4MS)—were inserted into the third-generation CAR backbone and were named IL13 CAR, IL13 (2MS) CAR, and IL13 (4MS) CAR, respectively. All three CAR cassettes were cloned into a lentiviral backbone, and the resultant plasmids were named pLenti-IL13 CAR, pLenti-IL13 (2MS) CAR, and pLenti-IL13 (4MS) CAR, respectively.

For the EphA2-specific CAR, EphA2 scFv was derived from EphA2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) 4H5, a humanized version of the EphA2 mAb EA2.51,52 The EphA2-specific scFv coding sequence was synthesized by Tsingke Biological Technology and was inserted into a third-generation CAR backbone, named EphA2 scFv CAR, and the final cassette was cloned into a lentiviral backbone and named pLenti-EphA2 CAR.

To construct the novel TanCAR, IL13 (4MS) was inserted separately into a third-generation CAR backbone, then EphA2 scFv was linked with it by a (GGGS)3 linker; this was named IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFV-TanCAR. Finally, the cassette of the IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR was cloned into a lentiviral backbone. The resultant plasmid was named pLenti-IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR.

Lentivirus production

Lentiviruses carrying the IL13 CAR, the IL13 (2MS) CAR, the IL13 (4MS) CAR, and theEphA2 scFv CAR or the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR were produced in HEK293T cells using transfection package cells with a three-plasmid system, according to a previously described protocol.53

Lentiviral transduction of Jurkat T cells for assaying the biological activity of the CAR based on a luciferase reporter system

A luciferase reporter gene with an upstream sequence of NFATs in Jurkat T cells can be used to assay T cell activation. The NFAT motif sequence was inserted into the pGL3-miniCMV luciferase vector (Promega). Then, the pGL3-8xNFAT-miniCMV-Luciferase cassette was inserted into EF1a-neomycin containing lentiviral vector, and the resultant plasmid was named pLenti-8xNFAT-miniCMV-Luciferase-EF1a-neomycin. High-titer lentiviral vectors were produced and concentrated according to previously described methods for the transduction of each CAR gene with a luciferase reporter gene in Jurkat T cells.53 Jurkat T cells carrying an NFAT-luciferase reporter gene were plated in a 24-well plate at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells per well approximately 24 h before viral infection in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), and the plate was incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were infected with lentivirus carrying the IL13 CAR, the IL13 (2MS) CAR, the IL13 (4MS) CAR, and the EphA2 scFv CAR or the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR, individually, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. All transduced and NT NFAT motif-luciferase Jurkat T cells were co-cultured with U87 or engineered K562 target cells at a 1 × 105:1 × 105 E:T ratio in the 24-well plate. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were collected for luciferase activity assay using a Varioskan Flash multitechnology microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Isolation and lentiviral transduction of human T cells

To generate CAR-T cells, peripheral blood samples were collected from healthy donors in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shaanxi Normal University. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Primary human CD8+ T cells were isolated from human PBMCs using a CD8+ T cell Isolation Kit, an LS Column, and a MidiMACS Separator according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Miltenyi Biotec, Meckenheim, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) and were activated with soluble anti-CD3 (2 μg/mL), soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL), and IL2, all from Sino Biological (Chesterbrook, PA). The activated primary human CD8+ T cells were infected with lentivirus carrying the IL13 CAR, the IL13 (2MS) CAR, the IL13 (4MS) CAR, and the EphA2 scFv CAR, or the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR, separately, at an MOI of 5 in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Then, the cells were spinoculated at 800 × g for 1.5 h at 32°C, and the plate was incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The culture media were replaced with fresh RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and IL2 (100 U/mL) 12 h after transduction. The second and third infections were conducted 5 and 10 days later, respectively. For expansion, both transduced and NT human primary CD8+ T cells were reactivated with anti-CD3 (2 μg/mL), soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL), and IL2 (100 U/mL) every three days. Both transduced and NT human primary CD8+ T cells were expanded in vitro safely for 14 days.

Quantitative PCR

To quantify the IL13Rα1, IL13Rα2, and EphA2 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels, total mRNA from the Jurkat T, U87, THP-1 cell lines was isolated by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The cDNA was then prepared via an Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using SYBR Green (Qiagen) with specific primer pairs for IL13Rα1 and IL13Rα2. The primers are shown in Table S2. The comparative Ct values of the genes of interest were normalized to the Ct value of β-actin (internal PCR control). The fold-difference in IL13Rα1 and IL13Rα2 mRNA levels compared to the U87 calibrator line was determined using the Livak method.54

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to confirm the expression of the single IL13 CAR, the IL13 (2MS) CAR, the IL13 (4MS) CAR, the EphA2 scFv CAR, or the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR on human primary CD8+ T cells by using mouse anti-flag mAb (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by DyLight-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Immunofluorescence was measured using a flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and analyzed with CytExpert software according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytotoxicity assays

To compare the cytotoxicity of the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells with IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells and IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, and NT CD8+ T cells were co-cultured individually with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells or the IL13Ra1+α2− THP-1 cell at E:T ratios of 20:1, 15:1, 10:1, 5:1, 4:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively. To compare the cytotoxicity of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells with that of the single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells and the EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells, and NT CD8+ T cells were co-cultured individually with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells at E:T ratios of 20:1, 15:1, 10:1, 5:1, 4:1, 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1, respectively. Then, culture supernatants were harvested 24 h later and used to assay the level of LDH using an LDH cytotoxicity kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytokine release assays

To compare the cytokine secretion function of the novel IL13 (4MS) CAR with IL13 CAR and IL13 (2MS) CAR in human primary CD8+ T cells novel IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells with IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells and IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (2MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, and NT CD8+ T cells were co-cultured individually with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells or the IL13Ra1+α2− THP-1 cell at an E:T ratio of 1 × 105:1 × 105 from triplicate wells and were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 24 h. To compare the cytokine secretion function of the novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR with that of the single IL13 (4MS) CAR and the EphA2 scFv CAR in human primary CD8+ T cells, single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells, and NT CD8+ T cells were separately co-cultured with EphA2+ and IL13Rα2+ U87 cells at an E:T ratio of 1 × 105:1 × 105 from triplicate wells and were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 24 h. Culture supernatants were harvested, and the production of IFN γ and IL2 was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (NeoBioscience, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Experiments in a xenograft nude mouse model

All animal studies were carried out under the standard protocol approved by Shaanxi Normal University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six- to 8-week-old male athymic nude mice were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co. (Xi'an, China) and were bred and maintained in-house under pathogen-free conditions. A total of 1 × 106 U87.eGFP.FFLuc cells were subcutaneously injected into the dorsal flank of each athymic nude mouse. After 5 days of expansion, when the tumor size had reached approximately 30–50 mm3, the mice were randomly assigned to five experimental groups. Group one mice (n = 5; the untreated group) were intratumorally injected with 100 μL of PBS. Group two mice (n = 5) were injected with 2 × 106 NT CD8+ T cells. Mice in groups three, four, and five (n = 5 per group) were injected with 2 × 106 single IL13 (4MS) CAR CD8+ T cells, EphA2 scFv CAR CD8+ T cells, and novel bispecific IL13 (4MS)-EphA2 scFv-TanCAR CD8+ T cells, respectively. The second injection was conducted 5 days later.

Bioluminescence imaging

Tumor progression or regression was monitored by bioluminescence imaging every week until the mice were euthanized. Isoflurane-anesthetized animals were imaged using the IVIS system (Xenogen IVIS Spectrum, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) 5–10 min after intraperitoneal injection with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin per mouse. The photons emitted from the luciferase-expressing tumor cells were quantified using Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). A pseudo-color image representing light intensity (with blue indicating least intense and red indicating most intense) was generated and superimposed over the grayscale reference image.

Tumor volume measurement

Tumor dimensions were measured every three days with electronic caliper, and tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: V = ½ × (length × width2), where the length was the greatest longitudinal diameter and width was the greatest transverse diameter.

Euthanasia of mice

On day 32 after tumor inoculation, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Tumors were resected immediately after euthanasia. The weight of the resected tumors was measured, and representative photographs of each group were taken.

Histological and immunohistochemical examinations

The tumor tissue samples, which had been resected from the euthanized mice, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The tissues were embedded in paraffin, and paraffin blocks were sectioned using a microtome. The adjacent sections of tumor tissue of each group were chosen for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical staining. Sections of tissue were transferred sequentially on the slide, and the slides were dried at 60°C for 20 min. Then, the dried slides were subjected H&E and immunohistochemical staining using standard procedures. For immunohistochemical staining, primary mouse anti-Ki67 mAb (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by secondary biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used to measure tumor cell proliferation, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primary rabbit anti-human CD3 antibody (Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China) followed by secondary biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratories) were used to show the accumulation of CAR-T cells in the tumor xenograft, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Window (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for the statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The differences between means were tested by using one-way ANOVA or t test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants to H.X. from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773265), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. GK202007023 and GK202107018), and the Key Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province (No. 2018SF-106) and research grants to X.Z. from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (SY20210003).

Author contributions

N.M., R.W., W.L., Z.Z., Y.C., Y.H., J.Z., and X.Z. conducted the experiments. H.X. and N.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Q.M. analyzed some experimental data and co-wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2022.02.012.

Supplemental Information

and S2

References

- 1.Linz U. Commentary on Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sathornsumetee S., Rich J.N., Reardon D.A. Diagnosis and treatment of high-grade astrocytoma. Neurol. Clin. 2007;25:1111–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhammad N., Mao Q., Xia H. CAR T-cells for cancer therapy. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2017;33:190–226. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2018.1430465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kong S., Sengupta S., Tyler B., Bais A.J., Ma Q., Doucette S., Zhou J., Sahin A., Carter B.S., Brem H., et al. Suppression of human glioma xenografts with second-generation IL13R-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:5949–5960. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed N., Salsman V.S., Kew Y., Shaffer D., Powell S., Zhang Y.J., Grossman R.G., Heslop H.E., Gottschalk S. HER2-specific T cells target primary glioblastoma stem cells and induce regression of autologous experimental tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:474–485. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampson J.H., Choi B.D., Sanchez-Perez L., Suryadevara C.M., Snyder D.J., Flores C.T., Schmittling R.J., Nair S.K., Reap E.A., Norberg P.K., et al. EGFRvIII mCAR-modified T-cell therapy cures mice with established intracerebral glioma and generates host immunity against tumor-antigen loss. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:972–984. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow K.K., Naik S., Kakarla S., Brawley V.S., Shaffer D.R., Yi Z., Rainusso N., Wu M.F., Liu H., Kew Y., et al. T cells redirected to EphA2 for the immunotherapy of glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:629–637. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada H., Low K.L., Kohanbash G., McDonald H.A., Hamilton R.L., Pollack I.F. Expression of glioma-associated antigens in pediatric brain stem and non-brain stem gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2008;88:245–250. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown C.E., Warden C.D., Starr R., Deng X., Badie B., Yuan Y.C., Forman S.J., Barish M.E. Glioma IL13Ralpha2 is associated with mesenchymal signature gene expression and poor patient prognosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arima K., Sato K., Tanaka G., Kanaji S., Terada T., Honjo E., Kuroki R., Matsuo Y., Izuhara K. Characterization of the interaction between interleukin-13 and interleukin-13 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24915–24922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton D.J., Zhang J.G., Metcalf D., Alexander W.S., Nicola N.A., Willson T.A. Cloning and characterization of a binding subunit of the interleukin 13 receptor that is also a component of the interleukin 4 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:497–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aman M.J., Tayebi N., Obiri N.I., Puri R.K., Modi W.S., Leonard W.J. cDNA cloning and characterization of the human interleukin 13 receptor alpha chain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:29265–29270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaPorte S.L., Juo Z.S., Vaclavikova J., Colf L.A., Qi X., Heller N.M., Keegan A.D., Garcia K.C. Molecular and structural basis of cytokine receptor pleiotropy in the interleukin-4/13 system. Cell. 2008;132:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oshima Y., Puri R.K. Characterization of a powerful high affinity antagonist that inhibits biological activities of human interleukin-13. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15185–15191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madhankumar A.B., Mintz A., Debinski W. Interleukin 13 mutants of enhanced avidity toward the glioma-associated receptor, IL13Ralpha2. Neoplasia. 2004;6:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80049-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs S., Chow K.K., Yi Z., Rodriguez-Cruz T., Hegde M., Gerken C., Ahmed N., Gottschalk S. T cells redirected to interleukin-13Ralpha2 with interleukin-13 mutein--chimeric antigen receptors have anti-glioma activity but also recognize interleukin-13Ralpha1. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson J.P., Debinski W. Mutants of interleukin 13 with altered reactivity toward interleukin 13 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:29944–29950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nash K.T., Thompson J.P., Debinski W. Molecular targeting of malignant gliomas with novel multiply-mutated interleukin 13-based cytotoxins. Crit. Rev. 2001;39:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wykosky J., Gibo D.M., Stanton C., Debinski W. EphA2 as a novel molecular marker and target in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3:541–551. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatano M., Eguchi J., Tatsumi T., Kuwashima N., Dusak J.E., Kinch M.S., Pollack I.F., Hamilton R.L., Storkus W.J., Okada H. EphA2 as a glioma-associated antigen: a novel target for glioma vaccines. Neoplasia. 2005;7:717–722. doi: 10.1593/neo.05277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grada Z., Hegde M., Byrd T., Shaffer D.R., Ghazi A., Brawley V.S., Corder A., Schonfeld K., Koch J., Dotti G., et al. TanCAR: a novel bispecific chimeric antigen receptor for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e105. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegde M., Mukherjee M., Grada Z., Pignata A., Landi D., Navai S.A., Wakefield A., Fousek K., Bielamowicz K., Chow K.K., et al. Tandem CAR T cells targeting HER2 and IL13Ralpha2 mitigate tumor antigen escape. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:3036–3052. doi: 10.1172/JCI83416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X., Zhang N., Shi H. Driving better and safer HER2-specific CARs for cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62730–62741. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krenciute G., Krebs S., Torres D., Wu M.F., Liu H., Dotti G., Li X.N., Lesniak M.S., Balyasnikova I.V., Gottschalk S. Characterization and functional analysis of scFv-based chimeric antigen receptors to redirect T cells to IL13Rα2-positive glioma. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:354–363. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charmsaz S., Beckett K., Smith F.M., Bruedigam C., Moore A.S., Al-Ejeh F., Lane S.W., Boyd A.W. EphA2 is a therapy target in EphA2-positive leukemias but is not essential for normal hematopoiesis or leukemia. PloS one. 2015;10:e0130692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown C.E., Starr R., Aguilar B., Shami A.F., Martinez C., D'Apuzzo M., Barish M.E., Forman S.J., Jensen M.C. Stem-like tumor-initiating cells isolated from IL13Rα2 expressing gliomas are targeted and killed by IL13-zetakine-redirected T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:2199–2209. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahlon K.S., Brown C., Cooper L.J., Raubitschek A., Forman S.J., Jensen M.C. Specific recognition and killing of glioblastoma multiforme by interleukin 13-zetakine redirected cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9160–9166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegde M., Corder A., Chow K.K., Mukherjee M., Ashoori A., Kew Y., Zhang Y.J., Baskin D.S., Merchant F.A., Brawley V.S., et al. Combinational targeting offsets antigen escape and enhances effector functions of adoptively transferred T cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:2087–2101. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahaman S.O., Sharma P., Harbor P.C., Aman M.J., Vogelbaum M.A., Haque S.J. IL-13R(alpha)2, a decoy receptor for IL-13 acts as an inhibitor of IL-4-dependent signal transduction in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1103–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown C.E., Badie B., Barish M.E., Weng L., Ostberg J.R., Chang W.C., Naranjo A., Starr R., Wagner J., Wright C., et al. Bioactivity and safety of IL13Ralpha2-redirected chimeric antigen receptor CD8+ T cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:4062–4072. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaghoubi S.S., Jensen M.C., Satyamurthy N., Budhiraja S., Paik D., Czernin J., Gambhir S.S. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with 18F-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2009;6:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown C.E., Alizadeh D., Starr R., Weng L., Wagner J.R., Naranjo A., Ostberg J.R., Blanchard M.S., Kilpatrick J., Simpson J., et al. Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:2561–2569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J.W., Young J.S., Solomaha E., Kanojia D., Lesniak M.S., Balyasnikova I.V. A novel single-chain antibody redirects adenovirus to IL13Ralpha2-expressing brain tumors. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18133. doi: 10.1038/srep18133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaroff S. CAR T-cell therapies with a bispecific twist: to bypass antigen escape, TanCAR and NanoCAR therapies take the bispecific route. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2018;38:24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Depoil D., Fleire S., Treanor B.L., Weber M., Harwood N.E., Marchbank K.L., Tybulewicz V.L., Batista F.D. CD19 is essential for B cell activation by promoting B cell receptor-antigen microcluster formation in response to membrane-bound ligand. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:63–72. doi: 10.1038/ni1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanetti S.R., Velasco-Hernandez T., Gutierrez-Agüera F., Díaz V.M., Romecín P.A., Roca-Ho H., Sánchez-Martínez D., Tirado N., Baroni M.L., Petazzi P., et al. A novel and efficient tandem CD19- and CD22-directed CAR for B cell ALL. Mol. Ther. 2021;30:550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai H., Wu Z., Jia H., Tong C., Guo Y., Ti D., Han X., Liu Y., Zhang W., Wang C., et al. Bispecific CAR-T cells targeting both CD19 and CD22 for therapy of adults with relapsed or refractory B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020;13:30. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00856-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah N.N., Johnson B.D., Schneider D., Zhu F., Szabo A., Keever-Taylor C.A., Krueger W., Worden A.A., Kadan M.J., Yim S., et al. Bispecific anti-CD20, anti-CD19 CAR T cells for relapsed B cell malignancies: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1569–1575. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiegel J.Y., Patel S., Muffly L., Hossain N.M., Oak J., Baird J.H., Frank M.J., Shiraz P., Sahaf B., Craig J., et al. CAR T cells with dual targeting of CD19 and CD22 in adult patients with recurrent or refractory B cell malignancies: a phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2021;27:1419–1431. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schneider D., Xiong Y., Wu D., Nӧlle V., Schmitz S., Haso W., Kaiser A., Dropulic B., Orentas R.J. A tandem CD19/CD20 CAR lentiviral vector drives on-target and off-target antigen modulation in leukemia cell lines. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2017;5:42. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0246-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tong C., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Ji X., Zhang W., Guo Y., Han X., Ti D., Dai H., Wang C., et al. Optimized tandem CD19/CD20 CAR-engineered T cells in refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2020;136:1632–1644. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020005278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang M., Tang X., Zhang Z., Gu L., Wei H., Zhao S., Zhong K., Mu M., Huang C., Jiang C., et al. Tandem CAR-T cells targeting CD70 and B7-H3 exhibit potent preclinical activity against multiple solid tumors. Theranostics. 2020;10:7622–7634. doi: 10.7150/thno.43991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maruta M., Ochi T., Tanimoto K., Asai H., Saitou T., Fujiwara H., Imamura T., Takenaka K., Yasukawa M. Direct comparison of target-reactivity and cross-reactivity induced by CAR- and BiTE-redirected T cells for the development of antibody-based T-cell therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:13293. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49834-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan R.A., Yang J.C., Kitano M., Dudley M.E., Laurencot C.M., Rosenberg S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grupp S.A., Kalos M., Barrett D., Aplenc R., Porter D.L., Rheingold S.R., Teachey D.T., Chew A., Hauck B., Wright J.F., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitzgerald J.C., Weiss S.L., Maude S.L., Barrett D.M., Lacey S.F., Melenhorst J.J., Shaw P., Berg R.A., June C.H., Porter D.L., et al. Cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Crit. Care Med. 2017;45:e124–e131. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vera J., Savoldo B., Vigouroux S., Biagi E., Pule M., Rossig C., Wu J., Heslop H.E., Rooney C.M., Brenner M.K., et al. T lymphocytes redirected against the kappa light chain of human immunoglobulin efficiently kill mature B lymphocyte-derived malignant cells. Blood. 2006;108:3890–3897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pule M.A., Straathof K.C., Dotti G., Heslop H.E., Rooney C.M., Brenner M.K. A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finney H.M., Akbar A.N., Lawson A.D. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J. Immunol. 2004;172:104–113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hombach A., Hombach A.A., Abken H. Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells: modification of the IgG1 Fc 'spacer' domain in the extracellular moiety of chimeric antigen receptors avoids 'off-target' activation and unintended initiation of an innate immune response. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damschroder M.M., Widjaja L., Gill P.S., Krasnoperov V., Jiang W., Dall'Acqua W.F., Wu H. Framework shuffling of antibodies to reduce immunogenicity and manipulate functional and biophysical properties. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:3049–3060. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coffman K.T., Hu M., Carles-Kinch K., Tice D., Donacki N., Munyon K., Kifle G., Woods R., Langermann S., Kiener P.A., et al. Differential EphA2 epitope display on normal versus malignant cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7907–7912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiscornia G., Singer O., Verma I.M. Production and purification of lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:241–245. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

and S2