Abstract

Drug administration should be considered a risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in younger healthy patients. We present a case of new‐onset pulmonary embolism (PE), possibly associated with excessive creatine supplement intake. A 24‐year‐old non‐smoker male presented to the emergency department with sudden‐onset dyspnoea and chest discomfort. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography and venography confirmed PE in the left and right pulmonary artery branches and a thrombus in the left popliteal vein. The patient had no family history of VTE, and other causes of thrombophilia were unlikely. He reported a recent increase in the intensity of his workouts and the dose of his creatine supplements in preparation for a bodybuilding competition. The creatine supplements likely promoted dehydration during intense workouts and profuse sweating. He received anticoagulation therapy, and the creatine supplements were discontinued. Creatine supplements should be used cautiously when there is a higher risk of becoming dehydrated.

Keywords: creatine supplement, dehydration, thromboembolism

We present a case of new‐onset pulmonary embolism, possibly associated with excessive creatine supplement intake.

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is commonly associated with immobility, thrombophilia and malignancy. However, other contributing factors, such as drug administration, should be considered in younger healthy patients. 1 Creatine is a common ingredient of nutritional supplements and ergogenic aids for athletes. 2 , 3 It is widely used without caution, although there is some concern over the possible risk of VTE from creatine intake. 3 , 4 We present a case of new‐onset bilateral pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), possibly associated with excessive creatine supplement intake and dehydration, in a previously healthy young man.

CASE REPORT

A 24‐year‐old non‐smoker man presented to the emergency department with sudden onset of dyspnoea and chest discomfort, which began 6 days prior. Additionally, he reported a 1‐week history of left calf pain without swelling. He denied any traumatic event prior to the onset of symptom. He works as a livestock farm worker. His medical and family histories were unremarkable, and he currently did not take any medications.

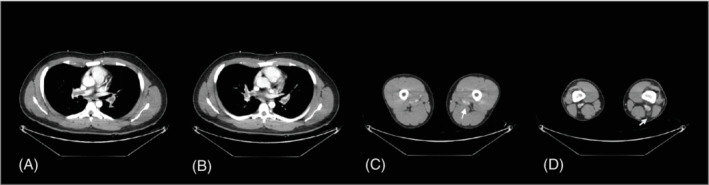

On admission, he had a blood pressure of 136/76 mmHg, pulse rate of 86 beats/min, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min and body temperature of 36.7°C. The oxygen saturation based on pulse oximetry was 95% in room air. The d‐dimer level was 5.67 μg/ml (reference value, 0–0.5 μg/ml). Computed tomography pulmonary angiography and venography revealed PE in the left and right pulmonary artery branches and a thrombus in the left popliteal vein (Figure 1). The patient had no family history of VTE. The comprehensive thrombophilia screening results, including the tests for homocysteine, antithrombin III, protein C activity, protein S activity, lupus anticoagulant, anti‐cardiolipin immunoglobulin M/immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti‐β2‐glycoprotein I IgG, were all normal.

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiography and venography images. Pulmonary embolism in both pulmonary arteries (A, B) and deep vein thrombosis in the left popliteal vein and left perforator vein (C, D) were noted

The patient's personal history was reassessed to investigate a possible provocative factor for the development of VTE. He has been regularly exercising at the gym after work for the last 5 years or more. His workouts last for at least 3 h daily. He has also been taking creatine monohydrate‐containing supplements daily to build his muscle mass. Recently, he increased the intensity of his workouts to participate in a bodybuilding contest for the first time. Additionally, he took more than 20 g/day of creatine monohydrate. This exceeded the recommended creatine maintenance dose of 5 g/day. He recounted that he felt considerably thirsty during his workouts.

He was diagnosed with PE and DVT, possibly associated with excessive creatinine use. He underwent anticoagulation for 6 months and has since stopped taking creatine supplements. The patient remained healthy without VTE recurrence during the outpatient follow‐up.

DISCUSSION

The auxiliary use of ergogenic aids by recreational and professional athletes can cause harmful side effects. 3 Thrombotic complication, one of the significant complications, is well known to be associated with use of androgenic anabolic steroids and erythropoietin. 3

Creatine monohydrate is a safe ingredient, which is labelled as a non‐toxic food substance under the conditions of its intended use, including energy drinks and protein powders, by the US Food and Drug Administration. 2 However, Tan et al. initially reported two cases of VTE, likely associated with creatine supplementation, in previously healthy young men. 4 They emphasized the risk of dehydration and thrombosis in individuals taking creatine.

Similar to the patients reported by Tan et al., 4 the patient in this case used creatine supplements to boost his exercise performance. Creatine monohydrate induces an osmotic effect by increasing the concentration of intracellular creatine, allowing water to move into the muscle. 3 Dehydration is a known risk factor for VTE as it increases blood viscosity. 5 The creatine supplements likely promoted dehydration during intense workouts with profuse sweating. Although strenuous‐intensity exercise may also increase the risk of thrombosis, there was no evidence for effort thrombosis in this patient. In addition, the typical regimen of creatine supplementation involves oral intake of 20 g/day for 5 days as a loading dose, followed by 5 g/day as a maintenance dose. 2 However, this patient ingested more than the recommended dose based on the observed safe level for creatine monohydrate of 5 g/day. 2 There are no convincing data regarding the negative effect of creatine supplementation with appropriate doses on body fluid balance. However, there is still a lack of data on causal association between dehydration and creatine supplementation with longer periods or higher dosage above the recommended daily amount. A new position statement from the European Association of Preventive Cardiology emphasizes that creatine use should be monitored carefully until more definitive data are obtained. 3 Adherence to the recommended dose and to stay hydrated when exercising seems important.

Although a causal relationship was not firmly established, this report suggested that excessive creatine use, which promoted dehydration, increased the risk of developing VTE. Creatine supplements should be used cautiously when there is a higher risk of becoming dehydrated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

So Hyun Lee: Writing – original draft. Jin A Seo: Methodology, writing – review. Ji Eun Park: Methodology, writing – review. Chang Ho Kim: Writing – review and editing, supervision. Jaehee Lee: Conceptualization, writing – review and editing, supervision. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors declare that appropriate written informed consent was obtained for the publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

Lee SH, Seo JA, Park JE, Kim CH, Lee J. A case of pulmonary thromboembolism possibly associated with the use of creatine supplements. Respirology Case Reports. 2022;10:e0932. 10.1002/rcr2.932

Associate Editor: Trevor Williams

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ramot Y, Nyska A, Spectre G. Drug‐induced thrombosis: an update. Drug Saf. 2013;36:585–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Food and Drug Administration GRAS Notice for Creatine Monohydrate. 2020 [cited 2021 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/143525/download.

- 3. Adami PE, Koutlianos N, Baggish A, Bermon S, Cavarretta E, Deligiannis A, et al. Cardiovascular effects of doping substances, commonly prescribed medications and ergogenic aids in relation to sports: a position statement of the sport cardiology and exercise nucleus of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan CW, Hae Tha M, Joo Ng H. Creatine supplementation and venous thrombotic events. Am J Med. 2014;127:e7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelly J, Hunt BJ, Lewis RR, Swaminathan R, Moody A, Seed PT, et al. Dehydration and venous thromboembolism after acute stroke. QJM. 2004;97:293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analysed during the current study.