Abstract

Specific human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) DNA sequences were found in leukocytes of 12 of 29 (41.4%) AIDS subjects with Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), whereas they were found in 4 of 43 (9.3%) AIDS subjects without KS (P = 0.003), although the peak HHV-8 DNA load in PCR-positive subjects with KS (mean, 425 copies per 0.2 μg of DNA) did not significantly differ from the one found in PCR-positive patients without KS (mean, 218 copies). The use of intravenous ganciclovir or foscarnet therapy to treat cytomegalovirus disease did not affect the HHV-8 DNA load in seven patients for whom serial samples were analyzed.

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus, is a new member of the γ-herpesvirinae subfamily that has been associated with AIDS- and non-AIDS-related KS (5, 11, 19), multicentric Castleman’s disease (22), and body cavity-based lymphoma (4). Specific HHV-8 DNA sequences have been detected in >95% of KS lesions from both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative persons, in 20 to 71% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HIV-infected subjects with KS, and in 0 to 11% of PBMCs from HIV-infected subjects without KS (5, 6, 11, 15, 19, 21, 24). Using semiquantitative PCR analysis, some investigators have determined the HHV-8 DNA load in KS lesions and adjacent unaffected skin from AIDS patients (8), in lymph node biopsy specimens from HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients with lymphoproliferative disorders (1), and in saliva from HIV-infected subjects with and without KS (15). However, very few data concerning the relationship between the viral DNA load in PBMCs and the presence of KS are available. In this study, we determined using quantitative-competitive PCR the HHV-8 load in leukocytes from HIV-infected subjects with and without KS. For a subset of these patients, we also assessed the systemic viral load in response to therapy against cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease.

EDTA-treated blood samples were collected from HIV-infected subjects who had CD4 T-cell counts of ≤250 × 106/liter and who were enrolled in a prospective CMV viremia surveillance study (3). Subjects were classified into four groups on the basis of the presence or absence of KS and CMV disease. For patients with CMV disease, blood samples were collected before treatment and at some time during conventional ganciclovir or foscarnet therapy. Blood samples were also obtained from HIV-seronegative subjects without KS to serve as controls. Leukocytes were collected after separation of blood on a 6% dextran gradient. Preliminary experiments showed that such a procedure results in a 28% decrease, on average, of the amount of PBMCs initially present in whole-blood samples. Leukocytes were resuspended in a lysing solution (1× PCR buffer; Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) and proteinase K (JCN Biomedical, Inc., Aurora, Ohio) to obtain a concentration of 104 leukocytes/μl or approximately 0.1 μg of cellular DNA/μl. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 56°C, and the proteinase K was then inactivated for 10 min at 95°C. The equivalent of 0.2 μg of DNA (corresponding to 2 × 104 leukocytes) from each sample was first used for qualitative PCR according to the protocol described by Chang et al. (5). Briefly, each 50-μl PCR mixture also included 100 pmol of each KS233 primer, 100 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Promega Corporation). Cycling conditions included an initial 2 min of denaturation at 94°C, followed by 36 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 58°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C, with a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. All negative samples were screened for PCR inhibitors by testing for the presence of the β-actin gene (3, 7).

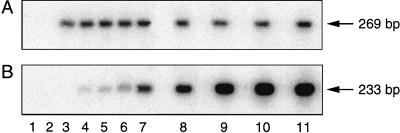

Samples that were positive by qualitative PCR were then retested in the quantitative-competitive assay. For this purpose, an external DNA standard was first synthesized by cloning the HHV-8-specific 233-bp amplified fragment (5) in the PCR 2.1 plasmid with the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen Corporation, San Diego, Calif.). An internal control (competitor) was created by inserting the HHV-8 primer sequences at both ends of a chosen DNA sequence (nucleotides 1925 to 2158) of the pt1713 cloning vector (Gibco BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) by the MIMIC PCR strategy (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). The competitor DNA and the external HHV-8 DNA standard had comparable sizes (269 versus 233 bp) and G+C contents (51.5 versus 51.9%) to ensure similar amplification efficiencies. One hundred copies of the competitor were added to serial dilutions (from 25 to 15,000 copies) of the external linearized DNA standard amplified in the presence of the appropriate DNA background (0.2 μg) from an HHV-8 DNA-negative blood donor and to lysed clinical samples. PCR conditions were similar to the ones used for the qualitative PCR assay except for the number of cycles (n = 30) and for the cycling time (30 s). Aliquots (12 μl) of each amplified product were run on two separate 1.5% agarose gels before Southern blot hybridization with a 25-bp HHV-8 probe (19) and a 23-bp internal control probe (CCATTGCTACAGGCATCGTGGTG) end labelled with [γ-32P]ATP. Radioactive hybrids were then analyzed with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunny Vale, Calif.). This system allows a value (integrated optical density [IOD]) for each specific band after subtracting the background noise obtained from blank samples. A standard curve was generated for each PCR assay by plotting on a graph the ratio of IOD values (IOD for HHV-8 external standard/IOD for HHV-8 competitor) obtained after amplification against the number of input HHV-8 copies. The original number of HHV-8 copies per 0.2 μg of DNA from patients was then determined by interpolating the ratio of the samples’ IOD values/IOD for the HHV-8 competitor into the standard curve of the assay. The intra- and interassay variabilities of the HHV-8 quantitative-competitive PCR were 25 and 32%, respectively, over a range of 25 to 5,000 copies. The CMV DNA load in the same leukocyte samples was determined as described previously (3).

The software package SAS System, version 6.12, for Windows was used for statistical analysis. A two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the percentage of HHV-8 or CMV DNA-positive samples between groups of patients.

Relationship between systemic HHV-8 DNA load and KS.

Specific HHV-8 DNA sequences were found on at least one occasion in 12 of 29 (41.4%) HIV-infected subjects with KS (33.3% of those with CMV disease [group A] versus 50.0% of those without CMV disease [group B]), whereas they were found in 4 of 43 (9.3%) of subjects without KS (15.0% of those with CMV disease [group C] versus 4.3% of those without CMV disease [group D]) (P = 0.003 for comparison between KS-positive and KS-negative subjects) (Table 1). As determined by quantitative-competitive PCR (Fig. 1), the peak HHV-8 DNA load for the 12 PCR-positive subjects with KS (mean, 425 copies per 0.2 μg of DNA; median, 16 copies; range, 12.5 to 4,341 copies) did not significantly differ from the one found for the 4 PCR-positive patients without KS (mean, 218 copies; median, 176 copies; range, 12.5 to 512 copies). Blood samples from 10 HIV-seronegative subjects without KS were all HHV-8 DNA negative.

TABLE 1.

HHV-8 DNA load in leukocytes of HIV-infected subjects

| Patient groupa | Presence of KSb | Presence of CMV disease | No. of HHV-8 DNA-positive subjects/total no. of subjects (%) | No. of HHV-8 DNA-positive samples/total no. of samples (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No therapy | On therapyc | Total | ||||

| A | Yes | Yes | 5/15 (33.3) | 9/22 (40.9) | 5/17 (29.4) | 14/39 (35.9) |

| B | Yes | No | 7/14 (50.0) | 8/28 (28.6) | 8/28 (28.6) | |

| A + B | Yes | Yes/no | 12/29 (41.4) | 17/50 (34.0) | 5/17 (29.4) | 22/67 (32.8) |

| C | No | Yes | 3/20 (15.0) | 7/24 (29.2) | 3/4 (75.0) | 10/28 (35.7) |

| D | No | No | 1/23 (4.3) | 1/23 (4.3) | 1/23 (4.3) | |

| C + D | No | Yes/no | 4/43 (9.3) | 8/47 (17.0) | 3/4 (75.0) | 11/51 (21.6) |

| Controlsd | 0/10 (0) | 0/10 (0) | 0/10 (0) | |||

For descriptions of the patient groups, see text.

Among the 29 subjects with KS, 19 had cutaneous involvement only, 7 had pulmonary involvement with or without skin involvement, and 3 had gastrointestinal disease.

Of the 21 samples, 16 were recovered during i.v. ganciclovir therapy and 5 were recovered during foscarnet therapy.

HIV-seronegative blood donors.

FIG. 1.

Quantitative-competitive PCR for HHV-8. Differential hybridization of PCR products was done with an internal control probe (A) and an HHV-8-specific probe (B). Lane 1, blank; lane 2, background of HHV-8 DNA-negative leukocytes; lane 3, 100 copies of the internal control in a background of HHV-8 DNA-negative leukocytes; lanes 4 to 11, 100 copies of the internal control coamplified with increasing concentrations of the HHV-8 external standard (25, 50, 100, 500, 1,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 15,000 copies, respectively) in a background of HHV-8 DNA-negative leukocytes.

Effect of anti-CMV therapy on HHV-8 DNA load.

To evaluate the effect of anti-CMV therapy (intravenous [i.v.] ganciclovir or foscarnet) on the systemic HHV-8 DNA load, blood samples from patients with CMV disease were analyzed before therapy and at different intervals during treatment. Sixteen samples from 13 subjects were recovered during ganciclovir therapy (mean number of days, 70.6 days; range, 4 to 600 days). In addition, 5 samples from 4 patients were analyzed during foscarnet treatment (mean number of days, 111.8 days; range, 3 to 202 days). As shown in Table 1, we found no difference in the percentage of HHV-8 DNA-positive blood samples analyzed during therapy compared with the percentage of HHV-8 DNA-positive samples analyzed pretherapy. More specifically, 29.4% of samples recovered during anti-CMV therapy from patients with KS were HHV-8 DNA positive, whereas 34.0% of samples obtained in the absence of therapy were HHV-8 DNA positive (P = 1.0). For KS-negative subjects, there was an increase in the rate of HHV-8 DNA positivity for samples analyzed during therapy (75.0%) versus the rate of HHV-8 DNA positivity for samples analyzed in the absence of therapy (17.0%), although too few samples were available during treatment for meaningful analysis. In contrast, the percentage of CMV PCR-positive blood samples recovered from patients with CMV disease (groups A and C; n = 35) decreased from 93.5% (in the absence of therapy) to 66.7% (during therapy) (P = 0.008; data not shown). Longitudinal analyses of the HHV-8 and CMV loads in blood samples from five HIV-infected subjects treated with i.v. ganciclovir and two patients treated with i.v. foscarnet are reported in Table 2. Both drugs induced a significant decrease in the CMV DNA load, generally followed by a rebound effect when therapy was stopped. In contrast, the HHV-8 DNA load appeared unaltered with such therapy and paradoxically slightly increased in four of five patients during ganciclovir treatment and two of two patients during foscarnet treatment.

TABLE 2.

Longitudinal analysis of the HHV-8 and CMV DNA loads during anti-CMV therapy in HIV-infected subjectsa

| Patient | Presence of KS | Blood sample no. (days of follow-upb) | Anti-CMV therapy, no. of days of anti-CMV therapy (cumulative no. of days)c | CMV load (no. of copies/μg of DNA) | HHV-8 load (no. of copies/0.2 μg of DNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Yes | 1 (1) | None | 723 | 4,341 |

| 2 (12) | On GCV, 5 (5)d | 0 | 6,437 | ||

| 3 (32) | Off GCV, 1 (24) | 0 | 301 | ||

| 4 (58) | Off GCV, 27 (24) | <25 | 44 | ||

| B | No | 1 (1) | None | 49,778 | 333 |

| 2 (14) | On GCV, 14 (14) | 71 | 1,918 | ||

| 3 (28) | Off GCV, 14 (14) | 2,799 | 251 | ||

| C | No | 1 (1) | None | <25 | <25 |

| 2 (17) | On GCV, 17 (17) | 0 | 663 | ||

| D | No | 1 (1) | None | 22,253 | 142 |

| 2 (26) | On FOS, 3 (3)e | 0 | 280 | ||

| 3 (54) | Off FOS, 22 (9) | 9,243 | <25 | ||

| 4 (90) | Off FOS, 58 (9) | 18,527 | 512 | ||

| E | Yes | 1 (1) | None | 1,479 | 0 |

| 2 (31) | On GCV, 31 (31) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 (84) | On GCV, 84 (84) | <25 | 253 | ||

| 4 (112) | Off GCV, 14 (98) | 84 | 371 | ||

| F | Yes | 1 (1) | None | 11,210 | 0 |

| 2 (48) | On GCV, 48 (48) | 0 | <25 | ||

| G | Yes | 1 (1) | None | 1,120 | <25 |

| 2 (54) | On FOS, 54 (54) | 0 | 42 |

All patients except patient D had CMV retinitis; subject D had CMV gastritis.

Day 1 is the baseline (within 24 h prior to CMV therapy).

Only systemic antiviral therapy is indicated. GCV, ganciclovir; FOS, foscarnet.

Patient received 7 days of foscarnet therapy prior to ganciclovir therapy.

Patient received 23 days of ganciclovir therapy prior to foscarnet therapy.

Although HHV-8 DNA is almost universally present in the KS lesions of HIV-positive subjects, only about half of these individuals harbor these specific viral sequences in their PBMCs (16, 20, 21, 23, 24). Additionally, HHV-8 DNA sequences are present in about 10% of HIV-infected subjects without KS (1, 15, 20, 21, 23, 24). Our results are in agreement with the results obtained in those studies since HHV-8 DNA was found significantly more frequently in the blood of KS-positive subjects (41%) than in the blood of subjects with similar CD4 T-cell counts but without KS (9%). On the other hand, the literature contains very few data concerning the clinical utility of quantitative assessment of the systemic HHV-8 DNA load as a marker for the development of KS. Using semiquantitative PCR analysis (based on the generation of a band after one-step or two-step PCR), Viviano et al. (23) found no obvious difference in the viral loads in blood from HIV-infected patients with or without KS. In contrast, the same investigators showed that positive samples from healthy Italian blood donors contained lower viral loads. Bigoni et al. (1) have also reported lower levels of HHV-8 DNA among HIV-seronegative blood donors than among HIV-seropositive patients, but the investigators did not report quantitative results for individuals with KS.

Using a reliable quantitative-competitive PCR assay, we found no difference in the HHV-8 DNA loads between KS-positive and KS-negative HIV-infected subjects. Thus, the measure of the circulating HHV-8 DNA load does not seem to correlate with the tumoral load. Furthermore, only four of seven subjects with pulmonary KS were positive for HHV-8 DNA in the blood, with only one subject having a viral load of >100 copies per 0.2 μg of DNA (data not shown). It is possible, however, that the intralesional viral load provides a better estimate of KS involvement. For instance, Dupin et al. (8) reported a higher viral DNA load in KS lesions than in apparently normal skin from the same patients. Clearly, more studies are needed to verify the relationship between the viral burden in the skin and the tumoral load.

Characterization of HHV-8, a herpesvirus, as the possible causal factor in the development of KS has led to analyses that have assessed the protective effects of antiherpesvirus drugs against the development of this disease. In retrospective studies, the use of foscarnet and perhaps ganciclovir but not acyclovir was associated with a reduced risk of KS (10, 13, 18). More recently, in vitro systems were developed to directly measure the susceptibility of HHV-8 to different drugs after the induction of lytic replication of the virus. These in vitro studies have generally confirmed the previous retrospective analyses and have also shown the very good activity of cidofovir (14, 17). However, the potential benefits of these agents in the treatment of KS require that active viral replication have an important role in the development and persistence of KS lesions.

Results from our study show that i.v. ganciclovir and foscarnet, given at doses leading to levels in serum higher than the estimated 50% inhibitory concentrations for CMV (about 2 μM for ganciclovir and 50 μM for foscarnet in our laboratory by the plaque reduction assay) and HHV-8 (about 5 μM for ganciclovir and 100 μM for foscarnet [14, 17]), induced a significant decrease in the blood CMV DNA load but not in the HHV-8 burden (Table 2). These results are in agreement with those of Humphrey et al. (12), who reported a persistence of HHV-8 DNA in the PBMCs of five HIV-infected subjects receiving ganciclovir and/or foscarnet therapy, although they provided no quantitative results. Thus, it is probable that most of the HHV-8 genome detected in the blood of these patients is from latent, nonreplicative viruses. Detection of HHV-8 lytic transcripts in the blood of these individuals should help to determine if active viral replication takes place when KS lesions are established (9).

There are some limitations in our study. First, we used a dextran sedimentation procedure to collect blood leukocytes as part of a CMV surveillance study. That procedure resulted in some loss in the amounts of PBMCs compared to a Ficoll-Hypaque method, as discussed above. However, this separation method did not seem to affect the detection of HHV-8 since our DNA positivity rate was similar to what has been found in most studies. On the other hand, a loss of PBMCs during the separation procedure might have resulted in a lower viral DNA load than expected since our results were expressed as the number of HHV-8 copies per 0.2 μg of leukocyte DNA. Nevertheless, such an observation would not change the conclusions of our study since the same procedure was used for both KS-positive and KS-negative subjects. Second, some caution is needed when interpreting the activity of foscarnet against the HHV-8 DNA load since only a few subjects received this drug (Tables 1 and 2).

In conclusion, we found that the presence of HHV-8 DNA in the blood was qualitatively but not quantitatively associated with the presence of KS in HIV-infected subjects. In addition, we found no immediate effects of ganciclovir or foscarnet on the systemic viral DNA load. Thus, unlike the situation with CMV (2, 3), the measure of the circulating HHV-8 DNA load does not appear to be a reliable surrogate marker for disease activity or response to antiviral drugs. We must emphasize, however, that larger studies with a prospective design are needed to confirm these preliminary observations. On the other hand, quantitative PCR assays could be valuable if there were other acute or chronic forms of HHV-8 infection in which active replication takes place. Also, our results do not preclude the possibility that active antiviral drugs may be beneficial in blocking viral replication at an early stage and prevent the development of KS in HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research. G.B. is a scholar of the Medical Research Council of Canada.

We thank Carole St-Pierre for excellent secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bigoni B, Dolcetti R, de Lellis L, Carbone A, Boiocchi M, Cassai E, Di Luca D. Human herpesvirus 8 is present in the lymphoid system of healthy persons and can reactivate in the course of AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:542–549. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin G, Chou S, Quirk M R, Erice A, Jordan M C. Detection of ganciclovir resistance mutations and quantitation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in leukocytes of patients with fatal disseminated CMV disease. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:523–528. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boivin G, Handfield J, Murray G, Toma E, Lalonde R, Lazar J G, Bergeron M G. Quantitation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in leukocytes of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects with and without CMV disease by using PCR and the SHARP Signal Detection System. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:525–526. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.525-526.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore P S, Said J W, Knowles D M. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin M S, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles D M, Moore P S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collandre H, Ferris S, Grau O, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Kaposi’s sarcoma and new herpesvirus. Lancet. 1995;345:1043. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90779-3. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delfau M H, Kerckaert J P, Collyn d’Hooghe M, Fenaux P, Lai J L, Jouet J P, Grandchamp B. Detection of minimal residual disease in chronic myeloid leukemia patients after bone marrow transplantation by polymerase chain reaction. Leukemia. 1990;4:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupin N, Grandadam M, Calvez V, Gorin I, Aubin J T, Havard S, Lamy F, Leibowitch M, Huraux J M, Escande J P, Agut H. Herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in patients with Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:761–762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flore O, Gao S J. Effect of DNA synthesis inhibitors on Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cyclin and major capsid protein gene expression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1229–1233. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glesby M J, Hoover D R, Weng S, Graham N M, Phair J P, Detels R, Ho M, Saah A J. Use of antiherpes drugs and the risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma: data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1477–1480. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y Q, Li J J, Kaplan M H, Poiesz B, Katabira E, Zhang W C, Feiner D, Friedman Kien A E. Human herpesvirus-like nucleic acid in various forms of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:759–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90641-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey R W, O’Brien T R, Newcomb F M, Nishihara H, Wyvill K M, Ramos G A, Saville M W, Goedert J J, Straus S E, Yarchoan R. Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cells: association with KS and persistence in patients receiving anti-herpesvirus drugs. Blood. 1996;88:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones J L, Hanson D L, Chu S Y, Ward J W, Jaffe H W. AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1995;267:1078–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.7855583. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kedes D H, Ganem D. Sensitivity of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication to antiviral drugs. Implications for potential therapy. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2082–2086. doi: 10.1172/JCI119380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koelle D M, Huang M-L, Chandran B, Vieira J, Piepkorn M, Corey L. Frequent detection of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in saliva of human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: clinical and immunologic correlates. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:94–102. doi: 10.1086/514045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchioli C C, Love J L, Abbott L Z, Huang Y Q, Remick S C, Surtento Reodica N, Hutchison R E, Mildvan D, Friedman Kien A E, Poiesz B J. Prevalence of human herpesvirus 8 DNA sequences in several patient populations. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2635–2638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2635-2638.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medveczky M M, Horvath E, Lund T, Medveczky P G. In vitro antiviral drug sensitivity of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. AIDS. 1997;11:1327–1332. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mocroft A, Youle M, Gazzard B, Morcinek J, Halai R, Phillips A N. Anti-herpesvirus treatment and risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma in HIV infection. AIDS. 1996;10:1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore P S, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1181–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore P S, Kingsley L A, Holmberg S D, Spira T, Gupta P, Hoover D R, Parry J P, Conley L J, Jaffe H W, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection prior to onset of Kaposi’s sarcoma. AIDS. 1996;10:175–180. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith M S, Bloomer C, Horvat R, Goldstein E, Casparian J M, Chandran B. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 DNA in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions and peripheral blood of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients and correlation with serologic measurements. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:84–93. doi: 10.1086/514043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, d’Agay M-F, Clauvel J-P, Raphael M, Degos L, Sigaux F. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viviano E, Vitale F, Ajello F, Perna A M, Villafrate M R, Bonura F, Arico M, Mazzola G, Romano N. Human herpesvirus type 8 DNA sequences in biological samples of HIV-positive and -negative individuals in Sicily. AIDS. 1997;11:607–612. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitby D, Howard M R, Tenant-Flowers M, Brink N S, Copas A, Boshoff C, Hatzioannou T, Suggett F E, Aldam D M, Denton A S, Miller R F, Weller I V D, Weiss R A, Tedder R S, Schulz T F. Detection of Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus in peripheral blood of HIV-infected individuals and progression to Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;346:799–802. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91619-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]