Abstract

Medicare Advantage (MA) is a public–private healthcare program for older adults and individuals with disabilities in the United States (US). MA enrollees receive their benefits from private health plans and the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries in MA plans continues to increase. MA plan enrollees typically have more socioeconomic risk factors compared to traditional Medicare enrollees. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of MA plans’ flexibilities to address socioeconomic risk factors, or social determinants of health (SDOH), and to tailor benefits and services to meet individual MA enrollee needs. Poor nutrition—often termed malnutrition or protein calorie malnutrition—is a problem for many Medicare beneficiaries. Malnutrition can prolong recovery and increase medical complications and readmissions. Up to half of older Americans are at risk for malnutrition or are malnourished. Nutrition-related supplemental benefits offered by MA plans can most effectively help address malnutrition and impact SDOH and quality outcomes as part of multi-modal interventions. Multi-modal interventions integrate quality nutrition care throughout the MA care process. This Editorial explores the issue of older adult malnutrition and SDOH and the nutrition-related supplemental benefits currently offered by MA plans. It also identifies opportunities for further nutrition benefit development and impact, including through integration in MA outcome measurements and quality frameworks.

Keywords: medicare advantage, malnutrition, social determinants of health, benefits, quality outcomes

What do We Already Know About This Topic?

Despite the importance of good nutrition, many older Americans do not have healthy diets, and malnutrition remains a health concern that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, including through increased food insecurity and health disparities that arise from social determinants of health (SDOH).

How Does Your Research Contribute to the Field?

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have the flexibility to address SDOH and malnutrition through supplemental benefits and are strengthening their SDOH-related internal capabilities and strategic partnerships which can provide a framework for MA plans to consider additional development of nutrition-related supplemental benefits.

What Are Your Research’s Implications Toward Theory, Practice, or Policy?

MA plans can build on the strong evidence base for nutrition’s ROI by linking nutrition-related supplemental benefits to the MA quality framework and integrating nutrition into MA plan quality improvement programs (QIPs) to help improve care processes and support SDOH and quality outcomes, particularly for high-risk populations including those with chronic conditions.

Introduction

As the United States (US) population ages, the number of Americans participating in Medicare grows. 1 Medicare is the federal government’s healthcare program for older adults and individuals with disabilities that today covers over 61 million lives. 2 Medicare Advantage (MA) is a public–private option where enrollees receive their benefits from private health plans. The percentage of Medicare beneficiaries choosing to enroll in MA plans is over 40% and continues to increase. 3

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought greater focus on longstanding health equity and disparity issues in the US. Enrollees in MA plans typically have more socioeconomic risk factors compared to traditional Medicare enrollees. 3 COVID-19 reinforced that socioeconomic risk factors, or social determinants of health (SDOH), are important contributors to health inequity and can negatively impact health outcomes and costs. 4 The pandemic also highlighted the importance of MA plans’ flexibilities to address SDOH and tailor benefits and services to meet individual enrollee needs. 5

MA plans are paid monthly capitated payments to provide care for each enrollee and must deliver at minimum the same benefits as traditional Medicare. Capitation incentivizes decreased healthcare utilization and promotes value-based care as well as positive health outcomes through a focus on primary care. Capitation also incentivizes innovation. MA plans can offer additional supplemental benefits—often at no extra cost to enrollees—to help reduce out-of-pocket costs and address medical/SDOH-related needs. For example, MA plans may offer nutrition-related supplemental benefits, including home-delivered meals for enrollees who have recently been hospitalized or have certain chronic conditions. 6

Poor nutrition—often termed malnutrition or protein calorie malnutrition—is a problem for many Medicare beneficiaries. Up to half of older Americans are at risk for malnutrition or are malnourished. 7 Malnutrition can prolong recovery and increase medical complications and readmissions. It is best addressed through timely and effective nutrition interventions. 7 Thus, nutrition-related supplemental benefits are important to improve both public health and MA organizational outcomes.

Nutrition-related supplemental benefits can be most effective when part of a multi-modal intervention that integrates quality nutrition care throughout the MA care process to impact SDOH and quality outcomes. This Editorial explores the issue of older adult malnutrition and SDOH and the nutrition-related supplemental benefits currently offered by MA plans. We also identify opportunities for further nutrition benefit development and impact, including through integration in MA outcome measurements and quality frameworks.

Poor Nutrition and Social Determinants of Health

Consistent evidence indicates healthy dietary patterns and body weight during adulthood are associated with decreased age-related impairments. Randomized clinical trials show disease-specific nutrition interventions slow progression and treat many common, aging-associated conditions. 8 Yet, despite the importance of good nutrition, as identified in the 2020–2025 US Dietary Guidelines for Americans, many older adults do not have healthy diets and malnutrition remains a health concern. 9 It is an issue for both underweight and overweight/obese individuals in part because the loss of lean body mass can decrease immune response and delay wound healing. 7

Malnutrition is associated with multiple poor health outcomes, including increased length of stay, readmission, frailty, and disability. 7 It can also lead to increased healthcare costs; disease-associated malnutrition in older adults costs an estimated $51.3 billion annually. 10 Malnutrition exists across the spectrum of healthcare, in hospitals, post-acute care settings, and in the community. However, it often remains unidentified and untreated even though it is preventable. 7

Older adults are at increased risk of malnutrition for many reasons, including those related to disease, functionality, social and mental health, and hunger and food insecurity. 7 Food insecurity is the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate, safe foods 11 and continues to disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority populations and low-income households. 12 Limited literacy in health and information technology are risk factors for malnutrition too, as they can impact the ability to find and use health information. 13 Malnutrition in older adults was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic in part due to intensified disparities, inequities, social isolation, 7 and increased rates of food insecurity. 14

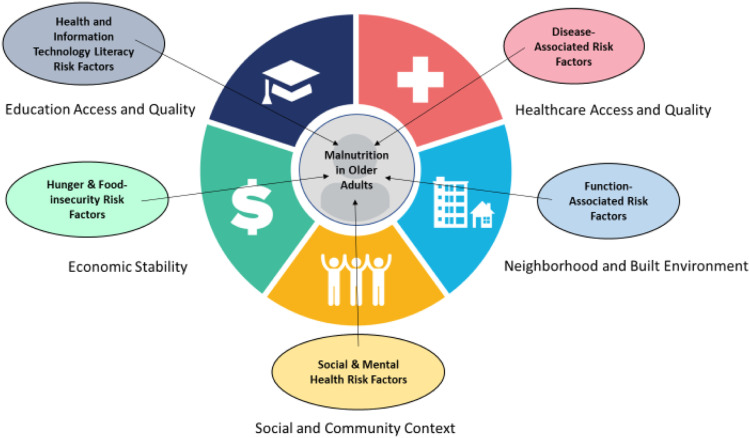

The malnutrition risk factors overlay each of the SDOH domains identified by Healthy People 2030 15 (Figure 1). MA plans are uniquely positioned to address the SDOH impacting malnutrition because their benefit flexibilities—including nutrition-related supplemental benefits—can lead to strong community partnerships with a potential for larger impact on beneficiary outcomes than clinical care alone.

Figure 1.

Overlay of older adult malnutrition risk factors and social determinants of health domains.15.

Medicare Advantage and Nutrition-Related Supplemental Benefits

The types of nutrition-related supplemental benefits and number of MA plans offering these benefits have grown as MA benefit flexibilities have expanded. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the US Congress recently granted MA plans new flexibilities in designing benefits with the goal of improving outcomes and lowering costs, particularly for enrollees with chronic conditions. In 2019, CMS expanded the definition of primarily health-related benefits to include nonmedical services, such as broader use of transportation, meal delivery, nutrition, and wellness services. With passage of the Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act of 2018, MA plans began in 2020 to offer nonmedical supplemental benefits unique to enrollees with specific chronic conditions. These benefits are part of the CHRONIC Care Act of 2018’s newly created Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI).

The number of MA plans offering certain nonmedical supplemental benefits—including meals—doubled between 2018 and 2020. 6 By 2021, over half (55%) of MA plans offered a meal benefit. 16 More MA plans offered other nutrition-related services as well, including nutrition and wellness counseling, access to fresh food and produce, and transportation for nonmedical needs (i.e., trips to a grocery store). 6 In 2021, new nutrition-related benefits introduced as part of SSBCI were grocery shopping and door drop, grocery delivery coverage, and gift cards to purchase certain defined healthy foods. 6

Nonmedical supplemental benefits can be particularly helpful for Special Needs Plans (SNPs). SNPs are for beneficiaries enrolled in MA and specifically focus on managing care of high-cost, high-need beneficiaries with chronic conditions, who are institutionalized, or who are also eligible for Medicaid. SNPs offer meals more frequently than non-SNPs, and SNP meal benefits are more generous both in duration and number of meals provided. Yet, of SNPs offering a meal benefit, most provide meals for 30 days or less per year, which presents an opportunity to further expand this benefit to better address enrollees’ longer-term nutrition needs and SDOH. 6

Through supplemental benefits, MA plans may also expand an existing Medicare benefit—such as medical nutrition therapy (MNT)—beyond the standard benefit that MA plans must provide under current law. Medicare defines MNT as “nutritional diagnostic, therapy, and counseling services for the purposes of disease management which are furnished by a RDN [registered dietitian nutritionist]…pursuant to a referral by a physician.” 17 MNT is evidence-based, individualized nutrition care that helps treat certain medical conditions and supports clinical therapies. It is different from and much more targeted than general nutrition education. 18 Thus, MNT can help address the patient-specific factors that impact malnutrition such as chronic disease and SDOH.

The standard Medicare MNT benefit covers a specified number of RDN visits for individuals with diabetes, kidney disease, or a recent kidney transplant. The Medical Nutrition Therapy Act of 2021 (MNT Act of 2021) has been introduced to expand standard Medicare MNT coverage to additional conditions, including malnutrition, prediabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, cancer, gastrointestinal disease, and cardiovascular disease. In addition, the MNT Act of 2021 would allow healthcare professionals beyond physicians to refer patients for MNT. 19

MA plans already have the ability to expand coverage for the number of visits, conditions, or both by offering MNT as a supplemental benefit. In 2020, 467 out of 4264 MA plans offered a supplemental MNT benefit; in 2021, the number decreased to 203 out of 4826 MA plans. 20 The reason for the decrease is uncertain but offers MA plans an area to explore further. There may also be need for additional beneficiary and provider education about MNT benefits since even traditional Medicare has historically very low MNT referral rates. 21

Opportunities for Further Nutrition Benefit Development and Impact

Nutrition-related supplemental benefits address important SDOH, and MA plans have a clear interest in offering these benefits. MA plans are strengthening their SDOH-related internal capabilities and strategic partnerships across 3 primary competencies: data sources and beneficiary identification, interventions, and evaluation. 22 These same areas can provide a framework for MA plans to consider opportunities for additional nutrition benefit development and impact too.

Data Sources and Beneficiary Identification

An estimated 1 in 2 older adults is at risk of malnutrition or is malnourished, 7 and nutritionally vulnerable older adults have reduced physical reserves that limit their recovery when faced with acute health threats or stressors. 23 Thus, it makes sense that MA plans target nutrition-related supplemental benefits like meals to enrollees recently discharged from the hospital. However, malnutrition is often not included among hospital discharge diagnoses. This is because malnutrition frequently goes unnoticed; malnutrition affects more than 30% of hospitalized patients 24 but is only diagnosed in 8% of hospital stays. 25

One way to identify beneficiaries at risk for malnutrition is to look for the risk factors outlined earlier in this Editorial, specifically those related to disease, function, social and mental health, hunger and food insecurity, and health and information technology literacy. Screening tools can also be used. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommends the Malnutrition Screening Tool for screening adults regardless of age, medical history, or setting. 26 Hunger Vital SignTM is a food insecurity screening tool validated for use with older adults. 27

Interventions

Nutrition interventions should be provided once malnutrition risk is identified. Many of the nutrition-related supplemental benefits MA plans offer are meals and/or nutrition services. A number of community-based organizations (CBOs), health systems, and other service providers already deliver these types of nutrition interventions (Table 1). Identifying such providers and pathways can help ease the burden MA plans may face in developing and aligning networks in local communities. However, some CBOs may not have the resources or capacity to contract with MA plans. 22 Reimbursement for services is another potential limitation, 22 underscoring the need for passage of the MNT Act of 2021.

Table 1.

Community-Based Providers of Nutrition Interventions.

| Provider | Business Model | Meal Services Offered | Nutrition Services Offered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not-for-profit organizations (older Americans Act home-delivered meal providers) 28 | Not-for-profit | Hot and/or frozen meals, food | Medical nutrition therapy (MNT), nutrition/wellness counseling a |

| Medically tailored meal providers 29 | Not-for-profit | Hot and/or frozen meals | MNT, nutrition/wellness counseling a |

| Commercial organizations30,31 | For-profit | Frozen meals | |

| Local hospitals/health systems 32 | Not-for-profit or for-profit | Hot and/or frozen meals, food a | MNT, nutrition/wellness counseling |

| Independent providers, 33 telehealth companies 34 | For-profit | MNT, nutrition/wellness counseling |

aMay not be available in some communities.

Evaluation

Evaluation of MA plans’ nutrition-related supplemental benefits can take several forms. First is utilization rate. Even as more MA plans offer nutrition-related supplemental benefits, there is uncertainty in utilization of the benefit. It takes time for MA plans to evaluate utilization, as multiple factors may have influence, including demographics, availability of community resources, and MA plans’ promotion of specific benefits to targeted enrollees. However, some nutrition-related supplemental benefits do appear to be popular. A recent survey of over 1200 Medicare enrollees receiving home-delivered meals reported 77% “enjoyed eating healthy meals significantly more than other health-related activities, such as taking medications [and] visiting the doctor.” 35

A second form of evaluation to consider is the return on investment (ROI) of nutrition-related supplemental benefits. While there is variation in who and how ROI is assessed, including by MA plans, nutrition interventions have strong and documented evidence of ROI and slow the progression of, and in some cases treat, many age-associated conditions. 8 Further, nutrition interventions in hospital settings are associated with reduced length of hospital stay/episode costs and positive returns on investments. 36 There is also a body of literature supporting MNT as cost-effective for treating chronic conditions, including obesity, diabetes, renal disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, HIV infection, and unintended weight loss. 37

Community-level nutrition interventions can have a positive ROI too. The Review of Evidence report for The Commonwealth Fund’s ROI calculator for partnerships to address the SDOH concludes “there is strong evidence that ensuring people have access to healthy food can significantly lower healthcare utilization and costs and result in an ROI.” The review specifically highlights findings of studies with home-delivered, medically tailored meals, home-delivered meals that are not medically tailored, and nondelivered food support programs, such as food pharmacies and the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). 38

A third form for evaluating MA nutrition-related supplemental benefits is related to MA quality programs. MA quality is measured using the Star Rating System as well as quality improvement programs (QIPs) developed by individual MA plans in accordance with CMS regulations. 39 There are multiple quality measures which can be impacted by nutrition (Table 2). Unfortunately, there are no MA quality measures specific to malnutrition. It has been recommended that CMS work with the healthcare community to identify potential quality measures for addressing SDOH within MA and the broader Medicare program. 22 Malnutrition risk screening could be an opportunity for a MA SDOH-related measure. The Global Malnutrition Composite Score measure 51 for acute care recently endorsed by the National Quality Forum includes malnutrition risk screening—this component could serve as a model for a MA quality measure.

Table 2.

Potential Impact of Nutrition on Medicare Advantage Quality Measures.

| Medicare Advantage (Part C) Star Rating measures 40 | Potential Impact of Nutrition | Required HEDISRa and CAHPSRb Measures (Reporting year 2022) 41 |

|---|---|---|

| Improving or maintaining physical health | Malnourished older adults make more visits to physicians, hospitals, emergency rooms and are more likely to experience healthcare-acquired conditions; malnutrition is linked to multiple poor health outcomes including: Increased mortality, immune suppression, infections, longer length of hospital stay, higher readmission rates, and higher treatment costs 7 | Hospitalization following discharge from a skilled nursing facility (30-day rate) |

| Plan all-cause readmissions Plan all-cause readmissions—observed-to-expected ratio—65+ years | ||

| Emergency department utilization—observed-to-expected ratio—total acute—65 + years | ||

| Hospitalization for potentially preventable complications—total acute and chronic ambulatory care-sensitive condition (ACSC)—observed-to- expected ratio—total | ||

| Improving or maintaining mental health | Nutrient intakes and energy balance can influence risk of developing mood disorders by affecting neurotransmitter levels, membrane fluidity, and/or by promoting vascular brain changes; malnutrition is also a risk factor for impaired mood 42 | |

| Special needs plan (SNP) care management | Malnutrition impacts body systems, including decreasing respiratory and cardiac function 7 | |

| Osteoporosis management in women who had a fracture | A spectrum of nutrients and trace elements are needed for bone health; nutrition may have an important role in prevention of secondary fractures 43 | Osteoporosis management in women who had a fracture |

| Diabetes-care—blood sugar controlled | Diet is an important part of diabetes care; nutrition interventions and counseling provided by an RDN as part of a healthcare team can result in significant improvements in body weight and blood sugar control 44 ; Malnutrition is a significant comorbidity affecting survival and healthcare costs in beneficiaries with diabetes 45 | Comprehensive diabetes care |

| Reducing the risk of falling | Malnutrition can lead to muscle wasting and functional loss, increasing risk of falls 7 ; very low protein intake may be a risk factor for predicting future falls in older adults with a history of falling 46 | Falls risk management |

| Nutrition has a central role in primary/secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease 47 ; there is strong evidence of the role of MNT in care of patients with heart failure 48 | Cardiac rehabilitation | |

| Dietary interventions can be effective in the prevention and management of hypertension 49 | Controlling high blood pressure | |

| Age-related disease states can benefit from careful attention to nutrition adequacy and a healthful diet; incorporating nutrition evaluations/services into older adult preventive care/wellness practices is central to avoiding and minimizing the effects of nutrition-related disease 50 | Adults’ access to preventive/ambulatory health services |

aHealthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

bConsumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

In addition to clinical effectiveness measures, the Star Rating System and QIPs also use patient satisfaction measures, which document enrollees’ opinions on a range of topics, including receiving needed care and rating of healthcare quality and health plans. Nutrition-related supplemental benefits could play an important role in impacting patient satisfaction measures. Older adults are interested in nutrition; a good understanding of and attitude towards nutrition can strongly and positively influence health status and quality of life. 52 In a 2018 survey of over 1000 Americans aged 50 years and older, most (77%) reported they were making at least some effort to eat the right amount of certain nutrients and the majority (60%) said they had better diet and lifestyle behaviors compared to their habits 20 years ago. 53 Yet in the same survey, low-income respondents were more likely than high-income respondents (50% and 41%, respectively) to report difficulty in eating a healthy diet, further underscoring the need to address health and nutrition inequities. 54

Lastly, there is an opportunity for MA plans to integrate nutrition-related supplemental benefits into their ongoing QIPs, including those specific to the chronic care improvement program (CCIP). CCIP initiatives are clinically focused and designed to improve the health of specific enrollees with chronic conditions. 55 These groups are likely to have the greatest need for and gain the most from effective nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention. Nutrition-focused QIPs that target care pathways and transitions can help improve care processes for these high-risk populations.

Although nutrition-focused QIPs specific to MA have not been identified in the literature, lessons from other care settings may be beneficial. An example of a successful nutrition-focused QIP model includes nutrition risk screening at healthcare institution admission, prompt initiation of oral nutrition supplements for at-risk patients, and nutrition education and follow-up. Such interventions have proven effective and are associated with cost-savings of $3186 per patient in the hospital setting 56 and cost-savings of $1558 per patient treated in the home health setting. 57 In the outpatient clinic setting, patients participating in a similar nutrition-focused QIP are associated with an 11.6% reduction in use of healthcare resources and net savings of $485 per patient treated. 58

Other examples of nutrition-focused QIPS include those based on the quality measures and tools developed by the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii). The MQii quality measures focus on optimizing malnutrition risk screening, nutrition assessment, documentation of malnutrition diagnoses, and development of nutrition care plans for malnourished patients, including recommended treatment plans. 59 As a result of implementing QIPs using MQii measures and tools, hospitals have significantly improved the identification of malnutrition and documented improved outcomes, 60 such as a 25% reduction in length of stay and 35.7% reduction in infection rates among patients who were malnourished or at risk of malnutrition. 61

Conclusion

Malnutrition is a common problem for older Americans, negatively impacting healthy aging and health outcomes. Malnutrition is exacerbated by food insecurity and health disparities that arise from SDOH. MA plans have the flexibility to address SDOH and malnutrition through supplemental benefits. MA plans can leverage their primary competencies in data sources and beneficiary identification, interventions, and evaluation. This includes building on the strong evidence base for nutrition’s ROI by linking nutrition-related supplemental benefits to the MA quality framework and required quality measures that can be impacted by nutrition. In addition, integrating nutrition into MA plan QIPs can help improve care processes and support SDOH and quality outcomes, particularly for high-risk populations including those with chronic conditions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MBA, KSR, KK, and WP outlined the approach as well as identified content and sources for this editorial. MBA drafted the initial manuscript. MBA, KSR, KK, and WP reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this editorial: MBA and KK are employees and stockholders of Abbott and KSR is an employee of the Better Medicare Alliance. WP has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Mary B. Arensberg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9825-2251

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Medicare Enrollment Services. Section . 2021. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-systems/cms-program-statistics/2019-medicare-enrollment-section. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation . Total Number of Medicare Beneficiaries. Timeframe. 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/total-medicare-beneficiaries/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D [Google Scholar]

- 3.Better Medicare Alliance. Data Brief : Social Risk Factors are High Among Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries Enrolled in Medicare Advantage. 2020. https://bettermedicarealliance.org/publication/data-brief-social-risk-factors-are-high-among-low-income-medicare-beneficiaries-enrolled-in-medicare-advantage/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 4.Singu S, Acharya A, Challagundla K, Byrareddy S. Impact of social determinants of health on the emerging COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Front Public Health. 2020;8:406. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AHIP. Social Determinants of Health and Medicare Advantage : Policy Recommendations to Achieve Greater Impact on Reducing Disparities & Advancing Health Equity for America’s Medicare Population. 2021. https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/SDOH-MA-IssueBrief-2021.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 6.Kornfield T, Kazan M, Frieder M, Duddy-Tenbrunsel R, Donthi S, Fix A. Medicare Advantage Plans Offering Expanded Supplemental Benefits: A Look at Availability and Enrollment. 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/feb/medicare-advantage-plans-supplemental-benefits. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 7.The Malnutrition Quality Collaborative . National Blueprint: Achieving Quality Malnutrition Care for Older Adults, 2020 Update. Washington, DC: Avalere Health and Defeat Malnutrition Today; 2020. https://www.defeatmalnutrition.today/sites/default/files/National_Blueprint_MAY2020_Update_OnlinePDF_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts SB, Silver RE, Das SK, et al. Healthy aging—nutrition matters: start early and screen often. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(4):1438-1448. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 2020. 9th Edition. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 10.Snider JT, Linthicum MT, Wu Y, et al. Economic burden of community-based disease-associated malnutrition in the United States. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(suppl 2):77S-85S. doi: 10.1177/0148607114550000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . Measurement. 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balasuriya L, Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK. Federal nutrition programs after the pandemic: learning from P-EBT and SNAP to create the next generation of food safety net programs. Inquiry. 2021;58:469580211005190. doi: 10.1177/00469580211005190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackert M, Mabry-Flynn A, Champlin S, Donovan EE, Pounders K. Health literacy and health information technology adoption: the potential for a new digital divide. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(10):e264. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashbrook A. Nearly 60 Percent Increase in Older Adult Food Insecurity During COVID-19: Federal Action on SNAP Needed Now. FRAC Chat Blog. 2020. https://frac.org/blog/nearly-60-percent-increase-in-older-adult-food-insecurity-during-covid-19-federal-action-on-snap-needed-now. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Healthy People 2030, Social Determinants of Health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freed M, Biniek JF, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage in 2021: Premiums, Cost Sharing, Out-of-Pocket Limits and Supplemental Benefits. 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2021-premiums-cost-sharing-out-of-pocket-limits-and-supplemental-benefits/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 17.US Code of Federal Regulations . Title 42, Chapter IV, Subchapter B, Part 410, Subpart G, § 410.132. Medical nutrition therapy. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/textidx?SID=7b0debeb5b121c3aad075234c34e6220&mc= true&node=se42.2.410_1132&rgn=div8 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. MNT Versus Nutrition Education. 2006. https://www.eatrightpro.org/payment/coding-and-billing/mnt-vs-nutrition-education. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- 19.117th Congress. S. 1536-Medical Nutrition Therapy Act of 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1536/text. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 20.Murphy-Barron C, Buzby EA, Pittinger S. Overview of Medicare Advantage Supplemental Healthcare Benefits and Review of Contract Year 2021 Offerings. Milliman Brief; 2021. https://bettermedicarealliance.org/publication/overview-of-medicare-advantage-supplemental-benefits-and-review-of-contract-year-2021-offerings/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhudy C, Shin E, Talbert JC. Rural/urban Disparities in Utilization of Medical Nutrition Therapy to the Fee-For-Service Medicare Population. Rural & Underserved Health Research Center Publications; 2020:13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=ruhrc_reports. Accessed October 14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Better Medicare Alliance, Center for Innovation in Medicare Advantage. Innovative Approaches to Addressing Social Determinants of Health for Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries. 2021. https://bettermedicarealliance.org/publication/report-innovative-approaches-to-addressing-social-determinants-of-health-for-medicare-advantage-beneficiaries/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 23.Starr KNP, McDonald SR, Bales CW. Nutritional vulnerability in older adults: a continuum of concerns. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4(2):176-184. doi: 10.1007/s13668-015-0118-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corkins MR, Guenter P, DiMaria-Ghalili RA, et al. Malnutrition diagnoses in hospitalized patients: United States, 2010. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(2):186-195. doi: 10.1177/0148607113512154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett ML, Bailey MK, Owens PL. Non-maternal and Non-neonatal Inpatient Stays in the United States Involving Malnutrition, 2016U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018. https://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp https://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skipper A, Coltman A, Tomesko J, et al. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: malnutrition (undernutrition) screening tools for all adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(4):709-713. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunderson C, Englehard EE, Crumbaugh AS, Seligman HK. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(8):1367-1371. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000180S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Administration for Community Nutrition Living. Services. 2021. https://acl.gov/programs/health-wellness/nutrition-services. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- 29.Food is Medicine Coalition. http://www.fimcoalition.org/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 30.GA Foods . Healthcare Nutrition. https://www.sunmeadow.com/what-we-offer/healthcare-nutrition-programs/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mom’s Meals. Health Plans . https://www.momsmeals.com/health-plans/

- 32.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics . RDNs and Medical Nutrition Therapy Services. 2021. https://www.eatright.org/food/resources/learn-more-about-rdns/rdns-and-medical-nutrition-therapy-services. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- 33.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics . Find a Nutrition Expert. https://www.eatright.org/find-a-nutrition-expert [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telenutrition NutriScape . Search for your Dietitian Specialist. https://telenutrition.nutriscape.net/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacphersonMom’s Meals Asks C. : How has COVID-19 Impacted Medicare Enrollee Attitudes Toward Their Benefits? Mom’s Meals blog. 2021. https://www.momsmeals.com/blog/for-healthcare-professionals/moms-meals-asks-how-has-covid19-impacted-medicare-enrollee-attitudes-toward-their-benefits/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 36.Philipson TJ, Snider JT, Lakdawalla DN, Stryckman B, Goldman DP. Impact of oral nutritional supplementation on hospital outcomes. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):121-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics . Medical Nutrition Therapy Act, Issue Brief for Academy Members. https://www.eatrightpro.org/-/media/eatrightpro-files/advocacy/legislation/mntactissuebrief2021_final.pdf?la=en&hash=E156E5408B3D12937B52FCA5FD8CFFBFF7B12409 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsega M, Lewis C, McCarthy D, Shah T, Coutts K. Review of evidence for health-related social needs interventions. ROI calculator for partnerships to address the social determinants of health. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/COMBINED_ROI_EVIDENCE_REVIEW_7.15.19.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 39.US Code of Federal Regulations. Title 42 CFR 422.152. Medicare Advantage Program Quality Improvement Program. 2007. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2007-title42-vol3/html/CFR-2007-title42-vol3-sec422-152.htm. Accessed December 14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicare. Medicare 2022 Part C & D Star Ratings Technical Notes. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2022-star-ratings-technical-notes-oct-4-2022.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 41.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicare. CMS II: Reporting Requirements for HEDIS® Measurement Year (MY) 2021, HOS, and CAHPS® Measures, and Information Regarding HOS and HOS-M for Frailty. 2021. https://www.hosonline.org/globalassets/hos-online/survey-administration/2022_reporting_requirements_for_hedis_hos_and_cahps.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 42.Harbottle L. The effect of nutrition on older people’s mental health. Br J Community Nurs. 2019;24(suppl 7):S12-S16. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.Sup7.S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higgs J, Derbyshire E, Styles K. Nutrition and osteoporosis prevention for the orthopaedic surgeon, a wholefoods approach. EFFORT Open Rev. 2017;2(6):300-308. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.160079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library . Medical Nutrition Therapy, MNT: Comparative effectiveness of MNT services. 2009. https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=4085&cat=3676 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed N, Choe Y, Mustad VA, et al. Impact of malnutrition on survival and healthcare utilization in Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6:e000471. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul MH, Arensberg MB, Simon JR, et al. Association between very low dietary protein intake and subsequent falls in community-dwelling older adults in the United States. OBM Geriatrics 2020;4(2):1-12. doi: 10.21926/obm.geriatr.2002120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler T, Kerley CP, Altieri N, et al. Optimum nutritional strategies for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation (BACPR). Heart. 2020;106(10):724-731. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library . Heart Failure, HF: Executive summary of recommendations. 2017. https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5289&cat=5570 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozemek C, Laddu DR, Arena R, Lavie CJ. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(4):388-393. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shlisky J, Bloom DE, Beaudreault AR, et al. Nutritional considerations for healthy aging and reduction in age-related chronic disease. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(1):17-26. doi: 10.3945/an.116.013474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valladares AF, McCauley SM, Khan M, D’Andrea C, Kilgore K, Mitchell K. Development and evaluation of a global malnutrition composite score. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;122(4):251-258. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeruszka-Bielak M, Kollajtis-Dolowy A, Santoro A, et al. Are nutrition-related knowledge and attitudes reflected in lifestyle and health among elderly people? A study across five European countries. Front Physiol. 2018;9:94. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.International Food Information Council Foundation . Nutrition Over 50, Using Food to Address Changing Health Concerns. 2018. https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IFIC-AO50-Survey-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 54.International Food Information Council. Low-income Americans over 50 Face Unique Health and Nutrition Hurdles, Compared to Others Their Age. 2018. https://ific.org/media-information/press-releases/low-income-americans-over-50-face-unique-health-and-nutrition-hurdles-compared-to-others-their-age/. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 55.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Managed Care Manual, Chapter 5—Quality Improvement Program. 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/HealthPlansGenInfo/Downloads/Chapter_5_April_10_2014.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2021.

- 56.Sulo S, Feldstein J, Partridge J, et al. Budget impact of a comprehensive nutrition-focused quality improvement program for malnourished hospitalized patients. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2017;10(5):262-270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riley K, Sulo S, Dabbous F, et al. Reducing hospitalizations and costs: a home health nutrition-focused quality improvement program. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(1):58-68. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong K, Sulo S, Wang W, et al. Nutrition program reduces healthcare use and costs of adult outpatients at nutritional risk. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45(S1):P38. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doley J, Phillips W, Talaber J, Leger-LeBlanc G. Early implementation of malnutrition clinical quality metrics to identify institutional performance improvement needs. J Acad Nut Diet. 2019;119(4):547-552. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valladares AF, Kilgore KM, Partridge J, Sulo S, Kerr KW, McCauley S. How a malnutrition quality improvement initiative furthers malnutrition measurement and care: results from a hospital learning collaborative. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45(2):366-371. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pratt KJ, Hernandez B, Blancato R, Blankenship J, Mitchell K. Impact of an interdisciplinary malnutrition quality improvement project at a large metropolitan hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9:e000735. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]