Abstract

Background

Azathioprine is used for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, but the therapeutic responses in randomised clinical trials have been conflicting.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of azathioprine for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis.

Search methods

Randomised clinical trials were identified by searching The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index Expanded, The Chinese Biomedical Database, and LILACS, and manual searches of bibliographies to September 2005.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials comparing azathioprine versus placebo, no intervention, or another drug were included irrespective of blinding, language, year of publication, and publication status.

Data collection and analysis

Our primary outcomes were mortality, and mortality or liver transplantation. Dichotomous outcomes were reported as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Continuous outcomes were reported as weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardised mean difference (SMD). We examined the intervention effects by random‐effects and fixed‐effect models.

Main results

We identified two randomised clinical trials with 293 patients. Only one of the trials was regarded as having low bias risk. Azathioprine did not significantly decrease mortality (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.31, 2 trials). Azathioprine did not improve pruritus at one‐year intervention (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.84, 1 trial), cirrhosis development, or quality of life. Patients given azathioprine experienced significantly more adverse events than patients given no intervention or placebo (RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.14 to 5.20, 2 trials). The common adverse events were rash, severe diarrhoea, and bone marrow depression.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence to support the use of azathioprine for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Researchers who are interested in performing further randomised clinical trials should be aware of the risks of adverse events.

Keywords: Humans; Azathioprine; Azathioprine/adverse effects; Azathioprine/therapeutic use; Immunosuppressive Agents; Immunosuppressive Agents/adverse effects; Immunosuppressive Agents/therapeutic use; Liver Cirrhosis, Biliary; Liver Cirrhosis, Biliary/drug therapy; Liver Cirrhosis, Biliary/mortality; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

There is no evidence to support azathioprine for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic disease of the liver that is characterised by destruction of bile ducts. Estimates of annual incidence range from 2 to 24 patients per million population, and estimates of prevalence range from 19 to 240 patients per million population. PBC primarily affects middle‐aged women. The forecast for the symptomatic patient after diagnosis is between 10 and 15 years. The cause of PBC is unknown, but the dynamics of the disease resemble the group 'autoimmune disease'. Therefore, one might expect a noticeable effect of administering an immune repressing drug (immunosuppressant). This review evaluates all clinical data on the immunosuppressant azathioprine in relation to PBC.

The findings of this review are based on two clinical trials with 293 patients. The drug azathioprine was tested versus placebo or no intervention. The primary findings of the review are that azathioprine has no effect on survival, itching, progression of the disease (cirrhosis development), or quality of life. Patients given azathioprine experienced more adverse events than patients given placebo.

Background

Primary biliary cirrhosis is a chronic liver disease of unknown aetiology. Ninety per cent of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis are females and the majority are diagnosed after the age of 40 years (James 1981). Over the past 30 years, substantial increases in the prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis have been observed (Kim 2000). Primary biliary cirrhosis is now a frequent cause of liver morbidity, and patients with primary biliary cirrhosis are significant users of health resources, including liver transplantation (Prince 2003).

Primary biliary cirrhosis is classically defined on the basis of the triad: antimitochondrial antibodies, found in over 95 per cent of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (Fregeau 1989; Lacerda 1995; Invernizzi 1997; Turchany 1997; Mattalia 1998); abnormal liver function tests that are typically cholestatic (with raised activity of alkaline phosphatases being the most frequently seen abnormality); and characteristic liver histological changes (Scheuer 1967) in the absence of extrahepatic biliary obstruction (Kaplan 1996). Patients may either be diagnosed during a symptomatic phase (the common symptoms being pruritus, fatigue, jaundice, liver enlargement, signs of portal hypertension, sicca complex, and scleroderma‐like lesions), in which case survival is significantly decreased, or during an asymptomatic phase, in which one has a relatively favourable prognosis (Beswick 1985; Balasubramaniam 1990). However, 40% to 100% of these patients will subsequently develop symptoms of primary biliary cirrhosis (Nyberg 1989; Metcalf 1996; Prince 2000).

Although the aetiology remains unknown, primary biliary cirrhosis is analogous to the graft‐versus‐host syndrome in which the immune system is sensitised to foreign proteins. Most primary biliary cirrhosis patients have increased class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) histocompatibility antigen expression on bile duct cells (Ballardini 1984; Van den Oord 1986), and cytotoxic T‐cells are infiltrating the bile duct epithelium (Yamada 1986). Other duct systems of the body with a high concentration of HLA class II antigens on their epithelium, such as the lacrimal and pancreatic glands, may be involved in the disease process (Epstein 1982).

Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis have been subjected to many drugs. Ursodeoxycholic acid (a bile acid) is the most extensively used drug in these patients (Verma 1999). Other drugs have been immunomodulatory and other agents, such as colchicine (Warnes 1987; Vuoristo 1995; Poupon 1996; Gong 2005b), prednisolone (Mitchison 1992; Prince 2005), chlorambucil (Hoofnagle 1986), cyclosporin A (Minuk 1988; Wiesner 1990; Gong 2005c), D‐penicillamine (Dickson 1985; Neuberger 1985; Gong 2004), methotrexate (Kaplan 1991; Lindor 1995; Gong 2005a), or azathioprine (Heathcote 1976; Christensen 1985).

Azathioprine is an immunosuppressant, suppressing delayed hypersensitivity and cellular cytotoxicity more than antibody responses. The immunosuppressive action of azathioprine depends on its conversion to active 6‐mercaptopurine by thiopurine S‐methyl‐transferase (Lennard 1992). Azathioprine is used for Crohn's disease (Pearson 1998), renal homotransplantation (Sandrini 2000), and severe, active rheumatoid arthritis (Suarez‐Almazor 2000). The first controlled therapeutic trial of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis showed no efficacy and suggested the possibility of significant toxicity of azathioprine therapy (Heathcote 1976). In contrast, a large multicenter trial showed evidence of efficacy with very little toxicity (Christensen 1985). We have been unable to identify meta‐analyses or systematic reviews on the beneficial and harmful effects of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis.

Objectives

To systematically assess the benefits and harms of azathioprine for primary biliary cirrhosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised clinical trials irrespective of blinding, language, year of publication, and publication status. We excluded studies using quasi‐randomisation (for example, allocation by date of birth). Since uncommon adverse events are rarely captured in randomised clinical trials, we also evaluate adverse events from non‐randomised, controlled studies and observational studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria of this review.

Types of participants

Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis, ie, patients having at least two of the following: elevated serum activity of alkaline phosphatases (or other markers of intrahepatic cholestasis), a positive result for serum mitochondrial antibody, and liver biopsy findings diagnostic for or compatible with primary biliary cirrhosis.

Types of interventions

Administration of any dose of azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention or other drugs. Co‐interventions were allowed as long as the intervention arms of the randomised clinical trial receive the same co‐interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Mortality.

Mortality or liver transplantation.

Secondary outcome measures

Pruritus: number of patients with pruritus at one‐year intervention.

Liver biopsy: number of patients who developed cirrhosis.

Quality of life: broad nature of a concept that includes physical functioning (ability to carry out activities of daily living such as self‐care and walking around), psychological functioning (emotional and mental well‐being), social functioning (social relationships and participation in social activities), and perception of health, pain, and overall satisfaction with life.

Adverse events (excluding mortality and liver transplantation): the adverse event is defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a patient in either of the two arms of the included randomised clinical trials, which did not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment, but did, however, result in a dose reduction, discontinuation of treatment, or registration of the advent as an adverse event/side effect in accordance with the ICH‐GCP guidelines (ICH‐GCP 1997).

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified randomised clinical trials in The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, which involves hand searches of major hepatology journals and conference proceedings, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index Expanded, The Chinese Biomedical Database, and LILACS (Royle 2003). We have given the search strategies in Appendix 1 with the time span of the searches.

We identified further trials by reading the reference lists of the identified studies. We wrote to the principal investigators to enquire about additional randomised clinical trials they might know of. We also contacted the pharmaceutical company (Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc) producing azathioprine to obtain any unidentified or unpublished randomised clinical trials.

Data collection and analysis

We performed the meta‐analysis following our protocol (Gong 2006) and the recommendations given by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2006) and the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Module (Gluud 2007).

Data extraction Two authors (YG and EC) independently evaluated whether the identified trials fulfil the inclusion criteria. We listed the excluded trials in 'Characteristics of excluded studies' with the reasons for exclusion. YG extracted data and EC validated the data extraction. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with CG.

Assessment of methodological quality We assessed the methodological quality of the randomised clinical trials using four components (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001):

Generation of the allocation sequence

Adequate, if the allocation sequence was generated by a computer or random number table. Drawing of lots, tossing of a coin, shuffling of cards, or throwing dice are considered as adequate if a person who was not otherwise involved in the recruitment of participants performed the procedure;

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used for the allocation sequence generation was not described.

Allocation concealment

Adequate, if the allocation of patients involved a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, identically appearing numbered drug bottles or containers prepared by an independent pharmacist or investigator, or sealed envelopes;

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used to conceal the allocation was not described;

Inadequate, if the allocation sequence was known to the investigators who assigned participants.

Blinding (or masking)

Adequate, if the trial was described as double blind and the method of blinding involved identical placebo or active drug;

Unclear, if the trial was described as double blind, but the method of blinding was not described;

Not performed, if the trial was not double blind.

Follow‐up

Adequate, if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals;

Unclear, if the report gave the impression that there had been no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated;

Inadequate, if the number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were not described.

We post hoc classified trials with at least two out of the four quality components, ie, adequate generation of the allocation sequence, adequate allocation concealment, and adequate blinding, as trials with low‐risk bias.

Characteristics of patients Number of patients randomised; mean (or median) age; sex ratio; histological stage; number of patients lost to follow‐up.

Characteristics of interventions Type, dose, and form of azathioprine intervention; type of intervention in the control group and collateral interventions; duration of treatment and follow‐up.

Characteristics of outcomes According to the protocol, outcomes were extracted from each included trial.

Statistical methods We used the statistical package RevMan Analyses 1.0.2 (RevMan 2003) provided by The Cochrane Collaboration. We presented dichotomous data as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and continuous outcome measures by weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% CI.

We examined intervention effects by using both a random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) and a fixed‐effect model (Mantel 1959) with the significant level set at P < 0.05. If the results of the two analyses led to the same conclusion, we presented only the results of the fixed‐effect model. In case of discrepancies of the two models, we reported the results of both models. We explored the presence of statistical heterogeneity by chi‐squared test with significance set at P < 0.10 and measured the quantity of heterogeneity by I2 (Higgins 2002) .

Sensitivity analyses For primary outcome measures, we used a method to pool uncertainty intervals, which incorporates both sampling error and the potential impact of missing data (Gamble 2005).

For secondary outcomes, we adopted 'available case analysis' at maximum reported follow‐up. Therefore, in the review, the number of patients in the denominator changed according to the secondary outcomes investigated.

Bias exploration Funnel plot was used to provide a visual assessment of whether treatment estimates were associated with study size. The performance of the available methods of detecting publication bias and other biases (Begg 1994; Egger 1997; Macaskill 2001) vary with the magnitude of the treatment effect, the distribution of study size, and whether a one‐ or two‐tailed test is used (Macaskill 2001). Therefore, we intended to use the most appropriate method having good trade‐off in the sensitivity and specificity, based on characteristics of the trials included in this review.

Results

Description of studies

We identified a total of 190 references through electronic searches of The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (n = 16), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library (n = 46), MEDLINE (n = 27), EMBASE (n = 79), and Science Citation Index Expanded (n = 22). We excluded 184 duplicates or clearly irrelevant references through reading abstracts. Accordingly, six references were retrieved for further assessment. Of these, we excluded one, which is listed under 'Characteristic of excluded studies' with reasons for exclusion. Accordingly, five references referring to two randomised clinical trials fulfilled our inclusion criteria and were included.

The two randomised clinical trials were parallel group trials published as full articles. All the included trials reported random allocation of 293 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis to azathioprine versus no intervention (Heathcote 1976) and azathioprine versus placebo (Christensen 1985).

The mean age of patients in the included trials was 53 years and 90% of the patients were women. Half patients had histological stage III or IV in Christensen 1985. The entry and exclusion criteria varied across trials, but were generally well‐defined, making it highly likely that all patients did have primary biliary cirrhosis. The dosage of azathioprine used in the Heathcote 1976 trial was around 30% higher than the one used in the Christensen 1985 trial. The trial duration (treatment plus follow‐up) was 5 years in the Heathcote 1976 and 11 years in the Christensen 1985 trials. Details are listed in the table of 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Risk of bias in included studies

Generation of the allocation sequence was adequate in the Christensen 1985 trial. Allocation concealment was adequate in both trials, which used the sealed envelope technique. Heathcote 1976 used no intervention as a control group; Christensen 1985 treated the control group with identically looking placebo. The follow‐up was adequately described in both trials: six patients were lost to follow‐up and one patient withdrew from the Heathcote 1976 trial; 63 patients were lost to follow‐up and 30 patients withdrew from the Christensen 1985 trial. We regard Christensen 1985 trial as a low‐bias risk trial.

Effects of interventions

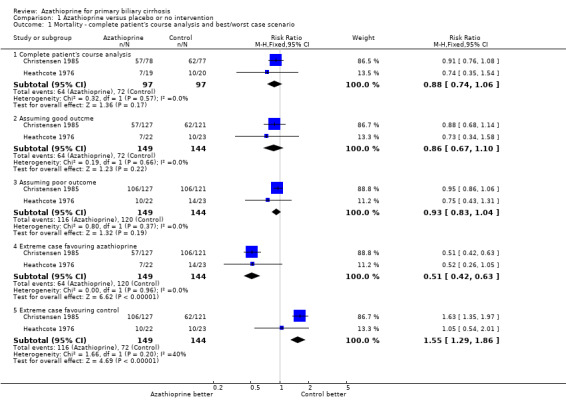

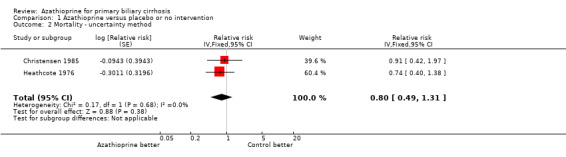

Mortality Seventeen patients died in the Heathcote 1976 trial, whereas 119 patients died in the Christensen 1985 trial. We did not see a significant difference in mortality between azathioprine and control when only data on available patients were included (RR 0.88, 95 CI 0.74, 1.06) (Comparison 01‐01). Considering the impact of missing data (eg, lost to follow‐up or patients withdrawn), azathioprine did not significantly reduce the mortality risk (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.31, pooled uncertainty intervals) (Comparison 01‐02).

Mortality or liver transplantation No patients were liver transplanted so this composite outcome could not be assessed.

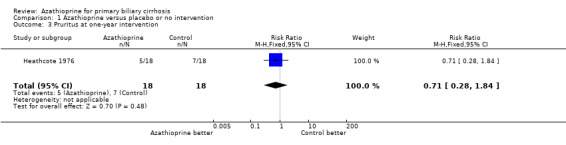

Pruritus at one‐year intervention At the start of the Heathcote 1976 trial, 18 of the 19 azathioprine‐treated and 16 of the 20 control patients complained of pruritus. At one‐year follow‐up, 5 of the 18 treated and 7 of the 18 control patients complained of pruritus (RR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.84). Pruritus data were not extractable in the Christensen 1985 trial.

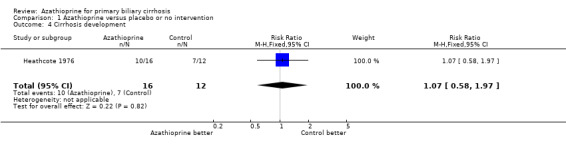

Hepatic histology Ten of the 16 treated patients and 7 of the 12 control patients had developed cirrhosis after entry to the Heathcote 1976 trial (RR 1.07, 95 % CI 0.58 to 1.97).

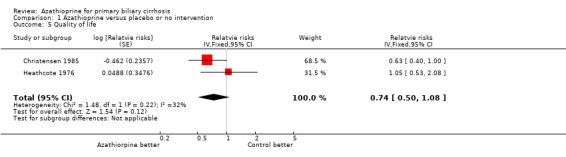

Quality of life Nine patients in each group remained fit and able to work for the whole period of the Heathcote 1976 trial. After combining data from the two trials, it seems that azathioprine did not improve the state of well‐being among patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.08).

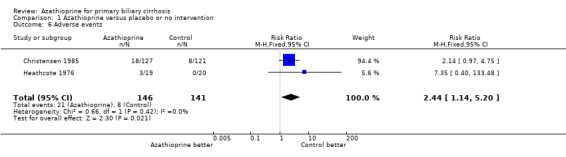

Adverse events Both trials reported adverse events. The pooled data showed that patients given azathioprine had experienced more adverse events than patients given nothing or placebo (RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.14 to 5.20). The common adverse events were rash, diarrhoea, and marrow depression. We were unable to extract data on fatigue, liver complication, and liver biochemistry.

Discussion

The results of our systematic review do not support azathioprine for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Patients given azathioprine experienced more adverse events than patients given nothing or placebo, though not all adverse events were severe.

To our knowledge, only two trials have been conducted to evaluate the role of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Therefore, this systematic review has a major limitation: a small number of trials included (Ioannidis 2001). The Heathcote 1976 trial included only 45 patients, did not use blinding, and only lasted five years. This is shorter than the estimated median survival of the disease, 10 to 15 years (Prince 2003).

Patients given azathioprine did not have significantly lower risk of death than patients given nothing or placebo. The rate of missing data was 16% in the Heathcote 1976 trial and 38% in the Christensen 1985 trial. It is important to take account of the influence of these missing data. We, therefore, performed a sensitivity analysis using the pooled uncertainty intervals to incorporate the potential impact of missing data and sampling error, which resulted in a RR 0.80 with 95% CI 0.49 to 1.31. This result gives consistent finding with the result conditional on data of available patients. During the five‐year follow‐up in the Heathcote 1976 trial, 17 patients died, and no difference in survival between the two groups was observed. Standard survival analysis in the Christensen 1985 trial revealed no significant difference between the two groups. However, when adjustment for imbalances between the two groups (primarily serum bilirubin) was made, there was a slight, but statistically significant difference in survival favouring azathioprine (P < 0.01). The first trial was clearly too small to have a reasonable chance of demonstrating or excluding any benefit of intervention. In contrast, the Christensen 1985 trial contained more patients with severe disease who were followed long enough to potentially showing an improvement in survival. However, even in this ideal clinical setting, demonstrating improvement in patient survival would still require statistical adjustment for baseline prognostic variables; this sort of analysis needs to be interpreted cautiously (Pocock 2002; Deeks 2003).

One of the most important subjective aspects of primary biliary cirrhosis is pruritus. Azathioprine did not improve the degree of pruritus, though there was a consistently smaller number of patients complaining of pruritus in the treated group than in the control group (not statistically significant) (Heathcote 1976). It was reported, in the Christensen 1985 trial that there was no significant difference in the number of patients requiring cholestyramine treatment for pruritus between the two groups. The Heathcote 1976 trial and the Christensen 1985 trial reported the results on liver biochemistry tests. However, we could not extract these data. There were no significant differences in the two groups in regard to the levels of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatases, aspartate transaminase, cholesterol, serum albumin, and serum immunoglobulin M in the Heathcote 1976 trial. The effect of azathioprine did not reach statistical significance for any biochemical variable in the Christensen 1985 trial. Ten of the 16 treated versus 7 of the 12 control patients had developed cirrhosis (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.97) in the Heathcote 1976 trial. There were no significant differences in the two groups in regard to intralobular inflammation, peripheral cholestasis, piecemeal necrosis, granulomas, fibrosis (without cirrhosis), and histologic stages in the Christensen 1985 trial.

Another important aspect is quality of life. Both Heathcote 1976 and Christensen 1985 measured this outcome in a similar manner. The Heathcote 1976 trial did not find a beneficial effect of azathioprine, whereas the Christensen 1985 trial claimed a marginal benefit (RR 0.63, P = 0.05). By pooling these two trials, we could not find a significant difference favouring azathioprine on quality of life (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.08).

The pooled data showed that patients given azathioprine had nearly 2.5 times more adverse events than patients given nothing or placebo (RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.14 to 5.20). Most of the patients who were withdrawn complained of rash, gastrointestinal disorder, and bone marrow depression. In addition, the immunosuppressive action of azathioprine depends on its conversion to active 6‐mercaptopurine by thiopurine S‐methyl‐transferase (Lennard 1992). Patients who inherit a thiopurine S‐methyl‐transferase deficiency accumulate excessive concentrations of the active thioguanine nucleotides in blood cells. This can lead to severe and potentially life‐threatening problems with the formation of blood cells among patients taking azathioprine.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to support azathioprine for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Patients taking azathioprine have higher risk of adverse events. Since patients with a thiopurine S‐methyl‐transferase deficiency would potentially have life‐threatening haematopoietic toxicity, prescription of azathioprine should be monitored by laboratory tests, including full blood count and liver function.

Implications for research.

Although the reviewed results of the two trials do not offer much optimism for a beneficial effect of azathioprine, researchers should recognize that only 293 patients have been randomised and the number of deaths were 136. These numbers may be considered too few, and investigators may wish to conduct further trials. If such trials are considered, then they ought to be closely monitored for both beneficial and adverse events. Any future trial should contain enough patients in concert with the sample size estimation, and patients should be followed long enough to allow observing potential improvement in survival. Any future trial ought to be reported according to the Consort Statement (www.consort‐statement.org).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We primarily extend our acknowledgements to the patients who took part in and the investigators who designed and conducted the reviewed trials. Dimitrinka Nikolova, Nader Salas, and Styrbjørn Birch, all from The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group, are thanked for expert assistance during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search Strategies

| Database | Period | Search term |

| The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register | September 2005. | 'primary biliary cirrhosis' and 'azathioprine' |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library | Issue 3, 2005. | #1 = LIVER CIRRHOSIS BILIARY: MESH #2 = primary and biliary and cirrhosis #3 = primary biliary cirrhosis #4 = pbc #5 = #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 #6 = AZATHIOPRINE: MESH #7 = IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS: MESH #8 = azathioprine #9 = #6 or #7 or #8 #10 = #5 and #9 |

| MEDLINE | January 1966 to September 2005. | #1 = LIVER‐CIRRHOSIS‐BILIARY: MESH #2 = primary and biliary and cirrhosis #3 = primary biliary cirrhosis #4 = PBC #5 = #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 #6 = AZATHIOPRINE: MESH #7 = IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS: MESH #8 = azathioprin* #9 = immunosuppressive agent* #10 = #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 #11 = #5 and #10 #12 = random* or placebo* or blind* or meta‐analysis #13 = #11 and #12 |

| EMBASE | January 1980 to September 2005. | #1 = PRIMARY‐BILIARY‐CIRRHOSIS: MESH #2 = BILIARY‐CIRRHOSIS: MESH #3 = primary and biliary and cirrhosis #4 = primary biliary cirrhosis #5 = PBC #6 = #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 #7 = AZATHIOPRINE: MESH #8 = IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS: MESH #9 = azathioprin* #10 = immunosuppressive agent* #11 = #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 #12 = #6 and #11 #13 = random* or placebo* or blind* or meta‐analysis #14 = #12 and #13 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (http://portal.isiknowledge.com/portal.cgi?DestApp=WOS&Func=Frame) | 1945 to September 2005. | #1 = TS=(primary biliary cirrhosis OR PBC) #2 = TS=(azathioprine OR azathioprin*) #3 = #2 AND #1 #4 = TS=(random* OR blind* OR placebo* OR meta‐analysis) #5 = #4 AND #3 |

| LILACS | 1982 to September 2005. | #1 = (primary and biliary and cirrhosis) or (primary biliary cirrhosis) #2 = primary biliary cirrhosis #3 = azathioprine #4 = (#1 OR #2) AND # 3 |

| Chinese Biochemical CD Database | January 1979 to September 2005. | #1 = LIVER‐CIRRHOSIS‐BILIARY: MESH #2 = primary and biliary and cirrhosis #3 = primary biliary cirrhosis #4 = PBC #5 = #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 #6 = AZATHIOPRINE: MESH #7 = IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE AGENTS: MESH #8 = azathioprin* #9 = immunosuppressive agent* #10 = #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 #11 = #5 and #10 #12 = random* or placebo* or blind* or meta‐analysis #13 = #11 and #12 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality ‐ complete patient's course analysis and best/worst case scenario | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Complete patient's course analysis | 2 | 194 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.74, 1.06] |

| 1.2 Assuming good outcme | 2 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.67, 1.10] |

| 1.3 Assuming poor outcome | 2 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.83, 1.04] |

| 1.4 Extreme case favouring azathioprine | 2 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.42, 0.63] |

| 1.5 Extreme case favouring control | 2 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.55 [1.29, 1.86] |

| 2 Mortality ‐ uncertainty method | 2 | Relative risk (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.49, 1.31] | |

| 3 Pruritus at one‐year intervention | 1 | 36 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.28, 1.84] |

| 4 Cirrhosis development | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.58, 1.97] |

| 5 Quality of life | 2 | Relatvie risks (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.50, 1.08] | |

| 6 Adverse events | 2 | 287 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.44 [1.14, 5.20] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 1 Mortality ‐ complete patient's course analysis and best/worst case scenario.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 2 Mortality ‐ uncertainty method.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 3 Pruritus at one‐year intervention.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 4 Cirrhosis development.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 5 Quality of life.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azathioprine versus placebo or no intervention, Outcome 6 Adverse events.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Christensen 1985.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: adequate, table of random numbers. Allocation concealment: adequate, sealed envelope technique. Blinding: identically looking placebo, no description of the taste and smell. Follow‐up: adequately reported, 29 in the azathioprine group and 34 in the control group were lost to follow‐up; 20 in the azathioprine group and 10 in the control group were withdrawn. | |

| Participants | Country: UK, Denmark, Spain, USA, Australia, Belgium, and France. Mean age: 54.7 years in the azathioprine group, 54.9 years in the control group. Female/Male: 222/26. PBC stage status Azathioprine group: 18, 56, 19, and 34 in stage I to IV, respectively. Placebo group: 15, 52, 18, and 36 in stage I to IV, respectively. |

|

| Interventions | Azathioprine: 300 to 700 mg/week (n = 127). Placebo: (n = 121). Treatment and follow‐up: 11 years. |

|

| Outcomes | (1) Mortality. (2) Clinical outcomes and liver biochemical variables. (3) Adverse events. (4) Quality of life. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Heathcote 1976.

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: unclear. Allocation concealment: adequate, sealed envelope technique. Blinding: no blinding. Follow‐up: adequately reported, 3 in the azathioprine group and 3 in the control group were withdrawn; 1 patient in the control group was lost to follow‐up. | |

| Participants | Country: UK. Mean age: 50.6 years in the azathioprine group, 51.7 years in the control group. Female/Male: 42/3. PBC stage status: pre‐cirrhotic patients. | |

| Interventions | Azathioprine: 2 mg/kg/day (n = 22). No intervention (control group): (n = 23). Treatment and follow‐up: 5 years. |

|

| Outcomes | (1) Mortality. (2) Clinical outcomes, liver biochemical, and hepatic histological variables. (3) Adverse events. (4) Quality of life. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Wolfhagen 1998 | A randomised trial comparing ursodeoxycholic acid, prednisone, and azathioprine versus ursodeoxycholic and placebo. |

Contributions of authors

YG performed the searches, selected trials for inclusion, wrote to authors, performed data extraction and data analyses with EC, and drafted the protocol and the systematic review. CG formulated the idea of this review and revised the protocol, selected trials for inclusion, validated, solved discrepancy of data extraction between YG and EC, and revised the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, Rigshospitalet, Denmark.

External sources

S.C. Van Foundation, Denmark.

Declarations of interest

None known. EC is the leading author of the Christensen 1985 trial. YG, EC, and CG have no affiliations or financial contracts with companies producing azathioprine.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Christensen 1985 {published data only}

- Christensen E, Altman DG, Neuberger J, Stavola BD, Tygstrup N, Williams R, et al. Updating prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis using a time‐dependent Cox regression model. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1865‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen E, Neuberger J, Crowe J, Altman DG, Popper H, Portmann B, et al. Beneficial effect of azathioprine and prediction of prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Final results of an international trial. Gastroenterology 1985;89(5):1084‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe J, Christensen E, Smith M, Cochrane M, Ranek L, Watkinson G, et al. Azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis: A preliminary report of an international trial. Gastroenterology 1980;78(5 I):1005‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heathcote 1976 {published data only}

- Heathcote J, Ross A, Sherlock S. A prospective controlled trial of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1976;70(5):656‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Sherlock S. A controlled trials of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis (abstract). Gut 1971;12(2):770. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Wolfhagen 1998 {published data only}

- Wolfhagen FHJ, Lim AG, Verma A, Buuren HR, Jazrwi RP, Northfield TC, et al. Soluble ICAM‐1 in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) during combined treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, prednisone and azathioprine (abstract). Netherlands Journal of Medicine 1995;47:A29. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfhagen FHJ, Buuren HR, Berge‐Henegouwen GP, Hattum J, Ouden JW, Kerbert MJ, et al. A randomized placebo‐controlled trial with prednisone/azathioprine in addition to ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis (abstract). Journal of Hepatology 1994;21(Suppl 1):S49. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfhagen FHJ, Buuren HR, Berge‐Henegouwen GP, Hattum J, Ouden JW, Kerbert MJ, et al. Prednisone/azathioprine treatment in primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). A randomized, placebo‐controlled trial (abstract). Netherlands Journal of Surgery 1995;46:A10. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfhagen FHJ, van Hoogstraten, Buuren HR, Berge‐Henegouwen GP, Kate FW, Hop WCJ, et al. Triple therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid, prednisone and azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis: a 1‐year randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Journal of Hepatology 1998;29:736‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Balasubramaniam 1990

- Balasubramaniam K, Grambsch PM, Wiesner RH, Lindor KD, Dickson ER. Diminished survival in asymptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 1990;98:1567‐71. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ballardini 1984

- Ballardini G, Mirakian R, Bianchi FB, Pisi E, Doniach D, Bottazzo GF. Aberrant expression of HLA‐DR antigens on bile duct epithelium in primary biliary cirrhosis: relevance to pathogenesis. Lancet 1984;2:1009‐13. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Begg 1994

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50(4):1088‐101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beswick 1985

- Beswick DR, Klatskin G, Boyer JL. Asymptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis: a progress report on long‐term follow‐up and natural history. Gastroenterology 1985;89:267‐71. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2003

- Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non‐randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment 2003;7(27):iii‐x, 1‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986;7(3):177‐88. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickson 1985

- Dickson ER, Fleming TR, Wiesner RH, Baldus WP, Fleming CR, Ludwig J, et al. Trial of penicillamine in advanced primary biliary cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1985;312(16):1011‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 1997;315(7109):629‐34. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epstein 1982

- Epstein O, Chapman RWG, Lake‐Bakaar G, Foo AY, Rosalki SB, Sherlock S, et al. The pancreas in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1982;83(6):1177‐82. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fregeau 1989

- Fregeau D, Water J, Danner D, Ansart T, Coppel R, Gershwin M. Antimitochondrial antibodies AMA of primary biliary cirrhosis PBC recognize dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase and inhibit enzyme function of the branched chain alpha ketoacid dehydrogenase complex. Faseb Journal 1989;3:A1121. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gamble 2005

- Gamble C, Hollis S. Uncertainty method improved on best/worst case analysis in a binary meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2005;58:579‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gluud 2007

- Gluud C, Nikolova D, Klingenberg SL, Als‐Nielsen B, D'Amico G, Davidson B, et al. Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group. About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)) 2007, Issue 2. Art. No.: LIVER.

Gong 2004

- Gong Y, Frederiksen SL, Gluud C. D‐penicillamine for primary biliary cirrhosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004789. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004789.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Gong 2005a

Gong 2005b

- Gong Y, Gluud C. Colchicine for primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2005;100:1876‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gong 2005c

- Gong Y, Christensen E, Gluud C. Cyclosporin A for primary biliary cirrhosis. (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD005526. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Gong 2006

- Gong Y, Christensen E, Gluud C. Azathioprine for primary biliary cirrhosis. (Protocol) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD006000. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Heathcote 1976

- Heathcote J, Ross A, Sherlock S. A prospective controlled trial of azathioprine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1976;70(5 Pt 1):656‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2002

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21:1539‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2006

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006]. The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

Hoofnagle 1986

- Hoofnagle JH, Davis GL, Schafer DF, Peters M, Avigan MI, Pappas SC, et al. Randomized trial of chlorambucil for primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1986;91(6):1327‐34. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ICH‐GCP 1997

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requiements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Code of Federal Regulation & ICH Guidelines. Media: Parexel Barnett, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Invernizzi 1997

- Invernizzi P, Crosignani A, Battezzati PM, Covini G, De‐Valle G, Larghi A, et al. Comparison of the clinical features and clinical course of antimitochondrial antibody‐positive and negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 1997;25(5):1090‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ioannidis 2001

- Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. Evolution of treatment effects over time: empirical insight from recursive cumulative metaanalyses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001;98(3):831‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

James 1981

- James O, Macklon AF, Waston AJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis ‐ a revised clinical spectrum. Lancet 1981;1(8233):1278‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaplan 1991

- Kaplan MM, Knox TA. Treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis with low‐dose weekly methotrexate. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1332‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaplan 1996

- Kaplan MM. Primary biliary cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;335(21):1570‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim 2000

- Kim WR, Lindor KD, Locke GR 3rd, Therneau TM, Homburger HA, Batts KP, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a U.S. community. Gatroenterology 2000;119:1631‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjaergard 2001

- Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodological quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta‐analyses. Annals of Internal Medicine 2001;135(11):982‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lacerda 1995

- Lacerda MA, Ludwig J, Dickson ER, Jorgensen RA, Lindor KD. Antimitochondrial antibody‐negative primary biliary cirrhosis. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1995;90(2):247‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lennard 1992

- Lennard L. The clinical pharmacology of 6‐mercaptopurine. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1992;43:329‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lindor 1995

- Lindor KD, Dickson ER, Jorgensen RA, Anderson ML, Wiesner RH, Gores GJ, et al. The combination of ursodeoxycholic acid and methotrexate for patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: the results of a pilot study. Hepatology 1995;22(4 Pt 1):1158‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Macaskill 2001

- Macaskill P, Walter SD, Irwig L. A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2001;20:641‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mantel 1959

- Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. Journal of National Cancer Institute 1959;22:719‐48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mattalia 1998

- Mattalia A, Quaranta S, Leung PS, Bauducci M, Van‐de‐Water J, Calvo PL. Characterization of antimitochondrial antibodies in health adults. Hepatology 1998;27(3):656‐61. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Metcalf 1996

- Metcalf J, Mitchison H, Palmer J, Jones D, Bassendine M, James O. Natural history of early primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet 1996;348(9039):1399‐402. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Minuk 1988

- Minuk GY, Bohme CE, Burgess E, Hershfield NB, Kelly JK, Shaffer EA, et al. Pilot study of cyclosporin A in patients with symptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1988;95:1356‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitchison 1992

- Mitchison HC, Palmer JM, Bassendine MF, Watson AJ, Record CO, James OF. A controlled trial of prednisolone treatment in primary biliary cirrhosis. Three‐year results. Journal of Hepatology 1992;15(3):336‐44. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 1998

- Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta‐analyses?. Lancet 1998;352(9128):609‐13. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuberger 1985

- Neuberger J, Christensen E, Portmann B, Caballeria J, Rodes J, Ranek L, et al. Double blind controlled trial of D‐penicillamine in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut 1985;26(2):114‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nyberg 1989

- Nyberg A, Loof L. Primary biliary cirrhosis: clinical features and outcome, with special reference to asymptomatic disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1989;24(1):57‐64. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pearson 1998

Pocock 2002

- Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21(19):2917–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poupon 1996

- Poupon RE, Huet PM, Poupon R, Bonnand AM, Nhieu JT, Zafrani ES, et al. A randomized trial comparing colchicine and ursodeoxycholic acid combination to ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 1996;24(5):1098‐103. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prince 2000

- Prince M, Jones D, Metcalf J, Craig W, James O. Symptom development and prognosis of initially asymptomatic PBC. Hepatology 2000;32(4 Pt 2):171A. [Google Scholar]

Prince 2003

- Prince MI, James OFW. The epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinics in Liver Disease 2003;7:795‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prince 2005

- Prince M, Christensen E, Gluud C. Glucocorticosteroids for primary biliary cirrhosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003778. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003778.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

RevMan 2003 [Computer program]

- Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.2 for Windows. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2003.

Royle 2003

- Royle P, Milne R. Literature searching for randomized controlled trials used in Cochrane reviews: rapid versus exhaustive searches. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 2003;19(4):591‐603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sandrini 2000

- Sandrini S, Maiorca R, Scolari F, Cancarini G, Setti G, Gaggia P, et al. A prospective randomized trial on azathioprine addition to cyclosporine versus cyclosporine monotherapy at steroid withdrawal, 6 months after renal transplantation. Transplantation 2000;69(9):1861‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scheuer 1967

- Scheuer P. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1967;60(12):1257‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273(5):408‐12. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suarez‐Almazor 2000

Turchany 1997

- Turchany JM, Uibo R, Kivik T, Van‐de‐Water J, Prindiville T, Coppel RL, et al. A study of antimitochondrial antibodies in a random population in Estonia. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1997;92(1):124‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van den Oord 1986

- Oord JJ, Sciot R, Desmet VJ. Expression of MHC products by normal and abnormal bile duct epithelium. Jounal of Hepatology 1986;3(3):310‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Verma 1999

- Verma A, Jazrawi RP, Ahmed HA, Northfield TC. Prescribing habits in primary biliary cirrhosis: a national survey. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 1999;11(8):817‐20. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vuoristo 1995

- Vuoristo M, Farkkila M, Karvonen AL, Leino R, Lehtola J, Makinen J, et al. A placebo‐controlled trial of primary biliary cirrhosis treatment with colchicine and ursodeoxycholic acid [see comments]. Gastroenterology 1995;108(5):1470‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Warnes 1987

- Warnes TW, Smith A, Lee FI, Haboubi NY, Johnson PJ, Hunt L. A controlled trial of colchicine in primary biliary cirrhosis: trial design and preliminary report. Jounal of Hepatology 1987;5(1):1‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiesner 1990

- Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, Lindor KD, Jorgensen RA, Baldus WP, Homburger HA, et al. A controlled trial of cyclosporine in the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1990;322(20):1419‐24. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yamada 1986

- Yamada G, Hyodo I, Tobe K, Mizuno M, Nishihara T, Kobayashi T, et al. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical analysis of lymphocytes infiltrating bile duct epithelia in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 1986;6(3):385‐91. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]