Abstract

In this work, a simple and versatile Schiff base chemosensor (L) was developed for the detection of four adjacent row 4 metal ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+) through colorimetric or fluorescent analyses. L could recognize the target ions in solutions containing a wide range of other cations and anions. The recognition mechanisms were verified with a Job’s plot, HR-MS assays, and 1H NMR titration experiments. Then, L was employed to develop colorimetric test strips and TLC plates for Co2+. Meanwhile, L was capable of quantitatively measuring the amount of target ions in tap water and river water samples. Notably, L was used for imaging Zn2+ in HepG2 cells, zebrafish, and tumor-bearing mice, which demonstrated its potential biological applications. Therefore, L can probably serve as a versatile tool for the detection of the target metal ions in environmental and biological applications.

Introduction

As is known to all, doubly charged metal ions such as Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ play important roles in the environment and biologic processes, especially in maintaining human nutrition and health.1 For instance, an excess of Co2+ could lead to vasodilatation and cardiomyopathy,1c,2 Similarly, an overload of Ni2+ would result in asthma, angina, or other cardiac symptoms.3 Daily intake of Cu2+ and Zn2+ is required to remain healthy.4 However, unregulated Cu2+ and Zn2+ may cause illness. For example, copper deficiency is associated with myelopathy.4c,4d,5 Conversely, the excess intake of Cu2+ can adversely affect human health.1e,2b,5 Non-regulatory Zn2+ levels could lead to Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, etc.6 Hence, the construction of a feasible method for the detection of the above four adjacent row 4 metal ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+) is urgently needed . To date, principal component feed-forward neural networks (PCFFNNs) and feed-forward neural networks (FFNNs) are the only reported methods for the detection of multiple metal ions.7 However, these methods are based on a series of complexation reactions7 and therefore suffer from several limitations, such as lengthy sample preparations and complicated calculation procedures.

Among many analytical methods, colorimetric and fluorescent analyses with small molecular chemosensors that can recognize various metal ions simultaneously are of vital importance because of their readily available and rapid operations (Table S1).7 Compared with the detection of an individual target ion, the exploration of multiple toxic metal ions with a single chemosensor is time- and cost-effective,7 which maximizes the convenience and economy of an analytical technique.8 Nevertheless, the development of chemosensors with the ability to detect multiple metal ions is a challenge,9,10 especially when those ions are adjacent in the periodic table.9,10

Chemosensors containing julolidine are usually water-soluble.11 2-Hydrazinylpyridine is capable of recognizing metal ions because it can form coordinate bonds with metal ions via its hydrazine group. Therefore, in this work we describe a simple chemosensor (L) consisting of the julolidine and 2-hydrazinylpyridine moieties (Scheme 1). The recognition properties of L for Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ ions were evaluated by colorimetric or fluorescent analyses. Moreover, L is able to image Zn2+ in live cells, zebrafish, and tumor-bearing mice.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Procedure for L.

Results and Discussion

The synthetic procedure to target chemosensor L is outlined in Scheme 1. In brief, 8-hydroxyjulolidine-9-carboxaldehyde and 2-hydrazinylpyridine were efficiently condensed in methanol under microwave irradiation for 15 min. L was perfectly characterized by NMR (1H and 13C), FT-IR, and mass spectrometry (MS) (Figures S1–S4).

The sensing behavior of chemosensor L was first investigated by absorption and fluorescence tests with various cations (Li+, Ag+, Cd2+, K+, Ca2+, Na+, Mg2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Al3+, Ba2+, Fe3+, Sr2+, and La3+) and different anions (CN–, I–, SCN–, NO3–, HSO4–, SO42–, Cl–, HCO3–, CO32–, ClO3–, PO43–, HPO42–, H2PO4–, Cr2O7–, S2–, MoO4–, Br–, and AcO–) in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40) at 25 °C.

After adding different concentrations of cations and anions (detailed above) to the L solution, only Cu2+ caused a prominent blue-shift in the absorption spectrum. Instead, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+ generated a remarkable red-shift in the absorption spectrum (Figures 1 and S5). Moreover, anions failed to induce any spectral response because of the absence of coordination between L and the anions (Figure S6). Besides, among the above four ions that showed obvious spectroscopic responses, only Co2+ caused the color of the solution to transform from colorless to wine-colored (Figures 1, S7 ,and S8). This is an increase from the longest spectral red-shift of L-Co2+ (among these four metal ions), which had a maximum absorption at 532 nm. The unique color transformation of L in response to Co2+ suggests that L could serve as a highly selective colorimetric chemosensor for Co2+ detection by the naked eye in aqueous solutions. Taken together, the above results demonstrate that L could be utilized as a versatile chemosensor for the synchronous measurement of target ions in aqueous solutions.

Figure 1.

Absorption spectra variation of chemosensor L (20 μM) before and after the addition of Co2+ (40 μM), Ni2+ (40 μM), Cu2+ (40 μM), and Zn2+ (40 μM) in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40). The inset shows the color change of L in response to Co2+.

The above solutions were also measured by fluorometry with an excitation wavelength of 413 nm. Only Zn2+ produced a distinct fluorescence intensity increase at 498 nm (ca. 10×) (Figure 2). By contrast, the fluorescence response for most of the other cations was negligible. The only change was Al3+, which gave an increase 3× the original intensity (Figure 2). Considering the abnormal accumulation of Cu2+ under certain illnesses conditions, L was also treated with high concentration of Cu2+ (200 μM). As shown in Figure S9, Cu2+ did not lead to a detectable fluorescence increase even at a high concentration. Moreover, in coexistence of Cu2+, the fluorescence induced by Zn2+ decreased slightly and remained constant over at least 1 h (Figure S10). Such a fluorescence decrease could be eliminated by the widely used chelation reagent resin Chelex-100 for Cu2+ (vide infra), implying that the chelated Cu2+ would not interrupt the fluorescence detection of Zn2+. In view of the fact that the intracellular Cu2+ is mainly the chelated form,12 the above results further indicated that L is capable of serving as a usable sensor for the fluorescence detection of an abnormal increase in the free Zn2+ level in living systems. It is worth mentioning that under UV lamp irradiation at 365 nm, Zn2+ could selectively induce the strong blue-green fluorescence of L, which could thus be applied for the naked-eye recognition of Zn2+ (Figures 2 and S11).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence spectra variation of chemosensors L (20 μM) before and after the addition of the above-mentioned cations (40 μM), where λex = 413 nm. The inset shows the visible fluorescence turn-on of L by Zn2+.

L can “turn on” fluorescence in response to Zn2+, which can be described as a result of the restricted Schiff base group (C=N) isomerization and the excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) mechanism.13 First, L exists as a free ligand in which the rotation of the C=N bond is not restricted. The rotation and isomerization of such an unrestricted C=N bond would act as a nonradiative inactivation process to quench the fluorescence of the fluorogen. Therefore, free L has no visible fluorescence. However, when Zn2+ is added to L, a chelate complex (with an enhanced rigid structure) may form between L with Zn2+ ion, resulting in the chelation-intensified fluorescence effect.13 Meanwhile, the intramolecular hydrogen bond (IMHB) between the phenolic O atom of julolidine shows ESIPT,13a,14 suggesting that the phenol O atom of julolidine could be chelated with Zn2+.13,14 Therefore, the chelation of Zn2+ by L may inhibit C=N isomerization and ESIPT, leading to an enhancement of the fluorescence (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Fluorescence Enhancement Mechanism of L by Zn2+ and the Proposed Structure of the L–Zn2+ Complex.

For further studies of the recognition responses between L and these four cations, absorption and fluorescence titration experiments were conducted. When L was added to increasing amounts of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+, the initial absorption peak of L at 370 nm gradually decreased and new peak presented. For Co2+, a new absorption peak emerged at 532 nm following the increase of the Co2+ concentration from 0 to 20 μM (Figure 3). For Ni2+, a new peak presented at 438 nm, and the absorption intensity gradually increased with the increase of the Ni2+ concentration from 0 to 60 μM, reaching its maximum at 60 μM of Ni2+ (Figure S12). For Cu2+, three new absorption peak appeared at 306, 416, and 520 nm as the concentration of Cu2+ increased from 0 to 400 μM (Figure S13). For Zn2+, an absorption peak emerged at 413 nm as the Zn2+ concentration increased from 0 to 100 μM, reaching its maximum at 100 μM of Zn2+ (Figure S14). The blue-shift of L-Cu2+ might be explained by the push–pull effect of the internal charge transfer (ICT) effect.15 When Cu2+ was added to L, the chelate complex of L–Cu2+ was formed through the phenol O, the Schiff base group (C=N) N, and secondary amine (−N−) N atoms complexing with Cu2+, which may have resulted in a feeble push–pull electronic effect. Therefore, the variation of the ICT transition mechanism could be responsible for blue-shift in the absorption spectrum. Meanwhile, the red-shift of the absorption peak shown by L–Co2+, L–Ni2+, and L–Zn2+ could be ascribed to ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) and the ICT effect in the complex formation.14 The energy gap of the ICT band should decrease upon M2+ (M = Co, Ni, and Zn) binding to the electron-donating groups, such as the phenol O atom, the Schiff base group (C=N) N atom, and the secondary amine (−N−) N atom, resulting in the red-shift of L–M2+.16 Moreover, the prominent isoabsorptive points were discovered at 398 nm for Co2+, 397 nm for Ni2+, 328 nm for Cu2+, and 392 nm for Zn2+, which indicated that just one complex was produced from L upon binding to Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, respectively. On the other hand, when fluorescence titration was conducted with Zn2+, the fluorescence intensity at 498 nm exhibited its maximum at 40 μM Zn2+ (Figure 4). The Job’s plots obtained from the absorption and fluorescence spectrum were applied to confirm the stoichiometry of the formed complexes. Figures 5, S15, and S16 demonstrate the 1:1 stoichiometry of L with Cu2+, Zn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectra of chemosensor L (20 μM) in the presence of 0–20 μM Co2+ in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of chemosensor L (20 μM) in the presence of 0–40 μM Zn2+ in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40).

Figure 5.

Job’s plots for metal ions with L. (a) Cu2+ (λmax = 306 nm) and (b) Zn2+ (λem = 498 nm), presenting a 1:1 stoichiometry in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40).

The stoichiometry results were further verified by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS). The HR-MS spectrum of the mixture of L with Co2+ (Figure 6) shows a peak at m/z 364.2441, which is assigned to [Co(L)]2+. Meanwhile, the HR-MS results of the mixtures of L with Ni2+, Zn2+, and Cu2+ did not show any homologous peaks for [Ni(L)]2+, [Zn(L)]2+, or [Cu(L)]2+. However, the peaks observed in Figures S17–19 at m/z 417.2923, 436.1867, and 438.2 could be attributed to [Ni(L)(Cl)(H2O)]2+, [Zn(L)(CH3CH2OH)(H2O)]2+, and [Cu(L) (CH3CH2OH)+Na+] (calcd. for 417.0628, 436.1265, and 438.1004), respectively. These study confirmed that L formed 1:1 complexes with Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+.

Figure 6.

HR-MS spectrum of L-Co2+ (1.0 eqv) in a 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40).

To further survey the bonding of chemosensor L to Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, 1H NMR titration tests were executed in a 10% D2O/DMSO-d6 mixed solvent (Figures 7 and S20–S22). As the concentrations of these metal ions increased, the phenolic −OH proton (Ha, δ 11.19 ppm) and −NH (Hb, δ 10.56 ppm) gradually weakened. The results indicated the complexation of the four metal ions with the phenolic O and N two atoms.11a,17 Meanwhile, when 1.0 equiv of the metal ion was added into the L solution, the phenolic −OH proton and −NH proton almost completely disappeared, indicating 1:1 complexation for [M(L)]2+ (M = Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+). In addition, the imine proton CH=N (Hc, δ 8.09 ppm) and benzene protons (Hd–Hi, δ 6.63–7.99 ppm) were disturbed and formed broader peaks due to the asymmetry of the [M(L)]2+ complexes.11a,17 Besides, the paramagnetic nature of Cu2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ is also a main reason for the quenching of the NMR signals. Therefore, 1H NMR titration experiments not only verified the binding sites of these four metal ions with L but also further confirmed the 1:1 complexation of [M(L)]2+.

Figure 7.

1H NMR tests of L with different concentrations of Zn2+ in a mixture of D2O/DMSO-d6 (v/v, 1:9).

To study the detection ability of L after being recycled for several measurements, the solution of L was alternately treated with metal ions and the strong chelating agent EDTA (Figures 8, S23, and S24). The initial absorbances of L-Co2+, L-Ni2+, L-Cu2+, and L-Zn2+ were recorded at 532, 438, 306, and 413 nm, respectively. After 1.0 equiv of EDTA was added to the L–M2+ solution, the absorbance of the system prominently decreased. Then, as more metal ions were added to the resulting solution of [L–(Co2+/EDTA)], [L–(Ni2+/EDTA)], [L–(Cu2+/EDTA)], or [L–(Zn2+/EDTA)], a recovery of the absorbance or fluorescence was observed. Furthermore, repeated experiments also yielded the same results for at least five cycles. Therefore, these competitive experiments with EDTA further verified the complexation durability of L with these four metal ions.

Figure 8.

Durability researches of L by the alternate treatment of (a) Ni2+ or (b) Zn2+ and EDTA in 50% ethanol/tris-HCl buffer solution (pH = 7.40).

Based on the above-mentioned experiments, the 1:1 complexation structures of L with four target ions are proposed in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3. Proposed Coordination Mechanism of L–M2+ (M2+ = Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+).

The linear relationships between absorption and the concentration of the four metal ions are shown in Figures S25–S28. Meanwhile, the association constants (Ka) of L with the four target ions were calculated using the Benesi–Hildebrand equation (Figures S29–S32).11a,18 The Ka values with L were calculated as 1.02 × 105, 1.35 × 105, 1.16 × 105, and 2.10 × 107 M–1 for Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, respectively. Furthermore, using 3σ/K (where σ is the standard deviation of 11 blank absorbances at the detection wavelength shown in Figures S25–S28 and K is the slope of the relative linear equation), the detection limits of L were calculated to be 3.20 × 10–8, 6.00 × 10–8, 6.23 × 10–7, and 1.09 × 10–7 M for Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, respectively.

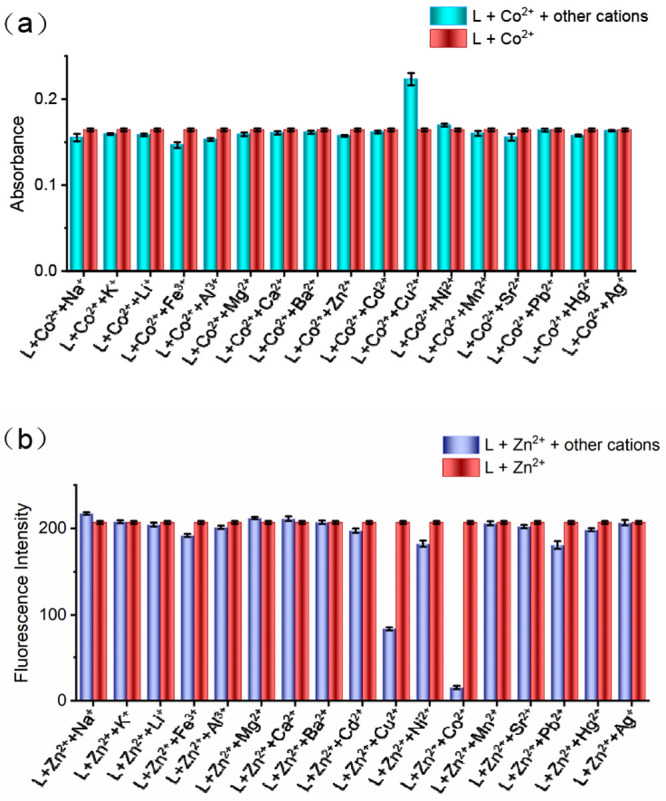

Next, the competitive tests were also performed by adding 2 equiv of 16 cations and 17 anions (as mentioned above) to the L–M2+ (M = Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+) system. The results showed that some metal ions would interfere with the absorption or fluorescence detection of the four metal ions (Figures 9 and S33–S38). For example, in the L–Co2+ and L–Ni2+ systems, the coexistence of other metal ions or anions did not influence the response to Co2+ and Ni2+ by chemosensor L expect for Cu2+ (Figures 9a and S33–35). However, the application of resin Chelex-100, a widely used chelation reagent for Cu2+, can eliminate the interference of Cu2+ for Co2+ and Ni2+, which is probably due to the stronger affinity between resin Chelex-100 and Cu2+ compared to Co2+ and Ni2+ (Figures S39 and S40, respectively).19 Therefore, L can serve as a selective chemosensor for the detection of Co2+ and Ni2+ even with the coexistence of 16 metal ions or 17 anions. For Cu2+, the absorption peak of L at 306 nm was not obviously interfered with by the other metal ions or anions except Fe3+ and Pb2+ (Figures S36 and S37, respectively). However, the interferences from Fe3+ and Pb2+ can be successfully inhibited using F– and EDTA, respectively (Figures S41 and S42, respectively). It should be noted that EDTA has comparable affinity to Pb2+ and Cu2+20 but may prefer to form a 1:1 complex with Pb2+ to remove its interference in the current system of L + Cu2+ + Pb2+ + EDTA, which is supported by our results. In the case of Zn2+, the fluorescence intensity of L–Zn2+ suffered from 60% or 90% quenching with the addition of Cu2+ or Co2+, respectively (Figure 9b). Fortunately, applications of triethanolamine and the chelating resin Chelex-100 were able to overcome the interferences from Co2+ and Cu2+ ions, respectively (Figure S43 and S44, respectively).

Figure 9.

Anti-interference experiments of L for metal ions. (a) Absorbance change of L–Co2+ before and after the addition of other different metal ions (2.0 equiv), where [L] = [Co2+] = 20 μM and λmax = 532 nm. (b) Fluorescence intensity of L–Zn2+ before and after the addition of other different metal ions (2.0 equiv), where [L] = [Zn2+] = 20 μM and λem = 498 nm.

In addition, we also tested the response time of chemosensor L to Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ (Figures S45–S47). The results show that L can rapidly recognize the four target ions and obtain a stable respond readout in a long time period.

To develop the practical application of L, test strips or TLC plates were coated with L for the naked-eye detection of Co2+ in water. Among the examined metal ions, a prominent color transformation from gray to wine red can be produced by only in the case of Co2+ (Figure 10a), implying the selective naked-eye detection of Co2+. In additional, the concentration of Co2+ can be quantitatively measured by naked eye using the test strips, and the detection limit was estimated to be 1.0 × 10–5 M. Furthermore, the L-coated TLC plates were also sprayed with different concentrations of Co2+. The results show that the L-coated TLC plates present an obvious color change from gray to wine, with an estimated detection limit of 1.0 × 10–4 M. Therefore, both L-coated test strips and L-coated TLC plates could be used for the rapid and easy detection of hazardous Co2+ by the naked eye in a real water sample (Figure 10b and c), which may position them as portable tools to be carried and used.

Figure 10.

Applications of the 20 μM L-coated test strips and TLC plates for the detection of Co2+. (a) The L-coated test strips sprayed with 40 μM solutions of different metal ions. (b) The L-coated test strips and (c) TLC plates sprayed with different concentrations of Co2+ (from left to right: 0.0, 1.0 × 10–6, 1.0 × 10–5, 1.0 × 10–4, 1.0 × 10–3, 1.0 × 10–2, and 1.0 × 10–1 M).

Next, L was utilized for the quantitative detection of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ in a variety of water samples such as tap water and river water (Table S2–S5, respectively). At the same time, the detection of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ in environmental water was also performed by ICP-MS assays, which obtained results comparable with those of L (Table S6–S9). These results further demonstrate that chemosensor L is highly usable in multiple fields such as environmental chemistry and analytical chemistry for the detection of the hazardous Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+.

To apply the chemosensor L in living cells for the fluorescence imaging detection of Zn2+, we first tested the cytotoxicity of L against HepG2 cells using the MTT assay.21 The results showed that L had a low cell inhibitory rate (Figure S48) and could be used as a biocompatible probe for the cellular imaging of Zn2+. As shown in Figure 11, inappreciable fluorescence was found when HepG2 cells were incubated with L for 30 min. However, after HepG2 cells were incubated with exogenous Zn2+ for other 30 min, strong fluorescence was observed under a fluorescence microscope (IX73). These experimental results indicate that chemosensor L is cell-penetrable and can serve as a valid candidate for the detection of Zn2+ in living cells by fluorescence imaging.

Figure 11.

Fluorescence imaging of Zn2+ in HepG2 cells with L. (a and b) Bright field images. (c and d) Fluorescence images of HepG2 cells treated with (c) L or (d) L + Zn2+. (e and f) Merged images of (e) panels a and c (f) panels d and b. [L] = [Zn2+] = 5 μM, λex = 425–485 nm, and λem = 515 nm.

To explore the possibility of detecting Zn2+ with L in living organisms, we performed fluorescence imaging in zebrafish or tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Figure 12, after being cultured with L for 30 min, the zebrafish was observed to have negligible fluorescence. However, the addition of Zn2+ to the L-loaded zebrafish led to a strong fluorescence enhancement under the fluorescence microscope. These results indicate that L could potentially be applied as a chemosensor for monitoring Zn2+ accumulation in living organisms.

Figure 12.

Fluorescence imaging of Zn2+ in zebrafish with L. (a and b) Bright field images. (c and d) Fluorescence images of zebrafish treated with (c) L or (d) L + Zn2+. (e and f) Merged images of (e) panels a and c and (f) panels b and d. [L] = [Zn2+] = 5 μM, λex = 425–485 nm, and λem = 515 nm.

To further expand the new application field of L for imaging Zn2+ in live animals, we also established a two-tumor model in C57 mice (one on each side) with B16F10 cells for the fluorescence imaging of Zn2+ in the tumors. As shown in Figure 13, it can be seen that the fluorescence signal was not detectable whether the mice were intratumorally injected with PBS (Figure 13a, right) or without PBS (Figure 13a, left), followed by intratumoral injection of Zn2+. Similarly, when only L was injected into the tumor, no fluorescence signal was observed (Figure 13b, left). However, the injection of Zn2+ resulted in a significant fluorescence increase within 10 min (Figure 13b, right). Overall, these studies indicate that L can be applied in live animals to image Zn2+.

Figure 13.

Fluorescence imaging of Zn2+ in B16F10 tumor-bearing C57 mice. (a) Fluorescence images of the mice intratumorally injected with only PBS for 10 min (left) and without PBS for 10 min (right), followed by an intratumoral injection of Zn2+ on both sides. (b) Fluorescence images of the mice intratumorally injected with L on both sides for 10 min, followed by an intratumoral injection of Zn2+ on the right side.

Conclusions

In summary, in this work we reported a simple and versatile chemosensor L, which can be used to recognize Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ ions. As for as we know, L is one of only a few cases of a simple chemosensor capable of sensing four metal ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+) that are adjacent on the fourth row of the periodic table. L could be used for the quantitative detection of trace amounts of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ in tap water and river water. Particularly, the selective colorimetry determination capacity of L for Co2+ enables it to be used for the naked-eye monitoring of Co2+ levels. More importantly, L can also be utilized to image Zn2+ in live cells, zebrafish, and tumor-bearing mice, demonstrating its potential application in biological systems. Therefore, L is expected to be employed as a simple and versatile chemosensor for the selective detection of environmental and biological traces of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ ions.

Experimental Section

All chemicals reagents were of analytical grade and applied without treatment. Double-distilled water was applied for all tests. The NMR tests were performed on an Agilent-400 DD2 spectrometer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) in DMSO-d6 with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. The chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in units of parts per million (ppm) relative to TMS. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) experiments were conducted on a time-of-flight Micromass LCT Premier XE spectrometer (McKinley Scientific, Sparta Township, NJ). Fluorescence spectra were recorded on a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a TU-1901 UV–vis spectrophotometer (PuXi Science and Technology Development Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). IR spectra were recorded on a Vary 1000 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). Fluorescence images of the cells were obtained by an Olympus IX73+DP73 inverted microscope. Small-animal living imaging was performed on IVIS Lumina LT Series III instrument (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). Additional experiment procedures are found in the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of Chemosensor L

A mixture of 8-hydroxyjulolidine-9-carboxaldehyde (0.23 g, 1 mmol) and 2-hydrazinylpyridine (0.10 g, 1 mmol) in MeOH (25 mL) was irradiated of 300 W at 60 °C for 15 min. After cooling the reaction mixture to an ambient temperature, the formed solid was filtered and washed with cold MeOH and diethyl ether. The crude product was purified by recrystallization from methanol to give 0.32 g of L as a yellow solid (85.1%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 1.83(s, 4H, −CH2−), 2.59(s, 4H, −CH2−), 3.11(s, 4H, −CH2−), 6.63(s, 1H, Ar–H), 6.70–6.71 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 6.74–6.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.58 (s, 1H, Ar–H), 7.99 (s, 1H, Ar–H), 8.09(s, 1H, CH=N), 10.58 (s, 1H, NH), 11.20 (s, 1H, OH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ (ppm): 156.20, 153.51, 144.34, 138.21, 127.40, 114.34, 138.21, 127.40, 114.34, 112.55, 107.01, 106.70, 105.53, 26.72, 21.82, 21.06, 20.54. IR (KBr, cm–1) ν: 3445, 2953, 1620, 1545, 1428, 1368, 1307, 1272, 1171, 967, 845, 775, 729. MS(ESI) calcd for C19H20N4O2 (M + H+): 310.2. Found: 310.2.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81660575 and 82060626), the Innovative Group Project of Guizhou Province of Education (KY[2018]024), the Excellent Youth Scientific Talents of Guizhou ([2021]5638), the Talents of Guizhou Science and Technology Cooperation Platform ([2020]4104), the Guizhou Science and Technology support plan ([2020]4Y158), and the Doctor Foundation of Zunyi Medical University (F-862) for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c05960.

Additional experiment procedures, spectra (UV–vis absorption, fluorescence, NMR, ESI-MS, and XRD), imaging data, and full reference information(PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Kim A.; Kang J. H.; Jang H. J.; Kim C. Fluorescent detection of Zn(II) and In(III) and colorimetric detection of Cu(II) and Co(II) by a versatile chemosensor. J. Indust. Engin. Chem. 2018, 65, 290–299. 10.1016/j.jiec.2018.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Anbu S.; Paul A.; Surendranath K.; Solaiman N. S.; Pombeiro A. J. A benzimidazole-based new fluorogenic differential/sequential chemosensor for Cu2+, Zn2+, CN–, P2O74-, DNA, its live-cell imaging and pyrosequencing applications. Sens Actuators, B 2021, 337, 129785. 10.1016/j.snb.2021.129785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Aysha T. S.; Mohamed M. B. I.; El-Sedik M. S.; Youssef Y. A. Multi-functional colorimetric chemosensor for naked eye recognition of Cu2+, Zn2+ and Co2+ using new hybrid azo-pyrazole/pyrrolinone ester hydrazone dye. Dyes Pigm. 2021, 196, 109795. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2021.109795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d He X.; Ding F.; Sun X.; Zheng Y.; Xu W.; Ye L.; Chen H.; Shen J. Reversible chemosensor for bioimaging and biosensing of Zn(II) and pH in cells, larval zebrafish, and plants with dual-channel fluorescence signals. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 5563–5572. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Hishimone P. N.; Hamukwaya E.; Uahengo V. The C2-symmetry colorimetric dye based on a thiosemicarbazone derivative and its cadmium complex for detecting heavy metal cations (Ni2+, Co2+, Cd2+, and Cu2+) collectively, in DMF. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 999–1008. 10.1007/s10895-021-02734-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a An Kim P.; Lee H.; So H.; Kim C. A chelated-type colorimetric chemosensor for sensing Co2+ and Cu2+. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 505, 119502. 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Keypour M. M.; Forouzandeh F.; Aza-dbakht R.; Khanabadi J.; Moghadam M. A. Synthesis and characterization of a new piperazine containing macroacyclic ligand and its Cu(II) and Co(II) complexes: An investigation of the ligand’s silver specific fluorescent properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1232, 130024. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Erten G.; Karcı F.; Demirçalı A.; Söyleyici S. 1H-pyrazole-azomethine based novel diazo derivative chemosensor for the detection of Ni2+. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1206, 127713. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lu W.; Chen J.; Shi J.; Li Z.; Xu L.; Jiang W.; Yang S.; Gao B. An acylhydrazone coumarin as chemosensor for the detection of Ni2+ with excellent sensitivity and low LOD: Synthesis, DFT calculations and application in real water and living cells. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 516, 120144. 10.1016/j.ica.2020.120144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kang J. H.; Lee S. Y.; Ahn H. M.; Kim C. A novel colorimetric chemo-sensor for the sequential detection of Ni2+ and CN– in aqueous solution. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 242, 25–34. 10.1016/j.snb.2016.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mudi N.; Hazra P.; Shyamal M.; Maity S.; Giri P. K.; Samanta S. S.; Mandal D.; Misra A. Designed synthesis of fluorescence ‘Turn-on’ dual sensor for selective detection of Al3+ and Zn2+ in water. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 315–325. 10.1007/s10895-020-02664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hazra A.; Roy A.; Mukherjee A.; Maiti G. P.; Roy P. Remarkable difference in Al3+ and Zn2+ sensing properties of quinoline based isomers. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 13972–13989. 10.1039/C8DT02856G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sağırlı A.; Bozkurt E. Rhodamine-based arylpropenone azo dyes as dual chemosensor for Cu2+/Fe3+ detection. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2020, 403, 112836. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d He X. J.; Xie Q.; Fan J. Y.; Xu C. C.; Xu W.; Li Y. H.; Ding F.; Deng H.; Chen H.; Shen J. L. Dual-functional chemosensor with colorimetric/ratiometric response to Cu(II)/Zn(II) ionsand its applications in bioimaging and molecular logic gates. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 177, 108255. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2020.108255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Tang A.; Yin Y.; Chen Z.; Fan C.; Liu G.; Pu S. A multifunctional aggregation-induced emission (AIE)-active fluorescent chemosensor for detection of Zn2+ and Hg2+. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 130489. 10.1016/j.tet.2019.130489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Rahimi H.; Hosseinzadeh R.; Tajbakhsh M. A new and efficient pyridine-2, 6-dicarboxamide-based fluorescent and colorimetric chemosensor for sensitive and selective recogni-tion of Pb2+ and Cu2+. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2021, 407, 113049. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.113049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Trevino K. M.; Tautges B. K.; Kapre R.; Franco F. C. Jr; Or V. W.; Balmond E. I.; Shaw J. T.; Garcia J.; Louie A. Y. Highly sensitive and selective spiropyran-based sensor for Copper(II) quantification. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10776–10789. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rha C. J.; Lee H.; Kim C. An effective phthalazine-imidazole-based chemosensor for detecting Cu2+, Co2+ and S2-via the color change. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 511, 119788. 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Pan W. Y.; Yang X. Y.; Wang Y. S.; Wu L.; Liang N.; Zhao L. S. AIE-ESIPT based colorimetric and “OFF-ON-OFF” fluorescence Schiff base sensor for visual and fluorescent determination of Cu2+ in an aqueous media. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2021, 420, 113506. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.113506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ghorai P.; Pal K.; Karmakar P.; Saha A. The development of two fluorescent chemosensors for the selective detection of Zn2+ and Al3+ ions in a quinoline platform by tuning the substituents in the receptor part: elucidation of the structures of the metal-bound chemosensors and biological studies. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 4758–4773. 10.1039/C9DT04902A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sun A. Q.; Wang W. X. Adenine deficient yeast: A fluorescent biosensor for the detection of Labile Zn(II) in aqueous solution. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113075. 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Su Z. Y.; Zhang H. L.; Gao Y.; Huo L.; Wu Y. G.; Ba X. W. Coumarin-anchored halloysite nanotubes for highly selective detection and removal of Zn(II). Chem. Engin. J. 2020, 393, 124695. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Ghorui T.; Hens A.; Pramanik K. Synthesis, photophysical properties and theoretical studies of pyrrole-based azoaromatic Zn(II) complexes in mixed aqueous medium. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 527, 120586. 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Afkhami A.; Abbasi-Tarighat M.; Khanmohammadi H. Simultaneous determination of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions in foodstuffs and vegetables with a new Schiff base using artificial neural networks. Talanta 2009, 77, 995–1001. 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rasouli Z.; Hassanzadeh Z.; Ghavami R. Application of a new version of GA-RBF neural network for simultaneous spectro-photometric determination of Zn(II), Fe(II), Co(II) and Cu(II) in real samples: An exploratory study of their complexation abilities toward MTB. Talanta 2016, 160, 86–98. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pothulapadu C. A. S.; Jayaraj A.; N S.; Priyanka R. N.; Sivaraman G. Novel benzothiazole-based highly selective ratio-metric fluorescent turn-on sensors for Zn2+ and colorimetric chemosensors for Zn2+, Cu2+, and Ni2+ ions. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24473–24483. 10.1021/acsomega.1c02855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li W.; Jiang C.; Lu S.; Wang F.; Zhang Z.; Wei T.; Chen Y.; Qiang J.; Yu Z.; Chen X. A hydrogel microsphere-based sensor for dual and highly selective detection of Al3+ and Hg2+. Sens. Actuators, B 2020, 321, 128490. 10.1016/j.snb.2020.128490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Wang F.; Wang K.; Kong Q.; Wang J.; Xi D.; Gu B.; Lu S.; Wei T.; Chen X. Recent studies focusing on the development of fluorescence probes for zinc ion. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 429, 213636. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Chen Y.; Wei T.; Zhang Z.; Chen T.; Li J.; Qiang J.; Lv J.; Wang F.; Chen X. A benzothiazole-based fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of Al3+ in aqueous medium and living cells. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 12267–12275. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b02979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu J. B.; Liu N.; Hao C. W.; Han Q. Q.; Duan Y. L.; Wu J. A novel fluorescence “on-off-on” peptide-based chemosensor for simultaneous detection of Cu2+, Ag+ and S2-. Sens Actuators, B 2019, 280, 129–137. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.10.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li H. Q.; Sun X. Q.; Zheng T.; Xu Z. X.; Song Y. X.; Gu X. H. Coumarin-based multi-functional chemosensor for arginine/lysine and Cu2+/Al3+ ions and its Cu2+ complex as colorimetric and fluorescent sensor for biothiols. Sens Actuators, B 2019, 279, 400–409. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu S. T.; Tan S.; Hu H.; Chen Z.; Pu S. Z. Novel colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor for Hg2+/Sn2+ based on a photochromic diarylethene with a styrene- linked pyrido[2, 3-b]pyrazine unit. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2021, 418, 113439. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.113439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Qin B.; Zhang X. Y.; Qiu J. J.; Gahungu G.; Yuan H. Y.; Zhang J. P. Water- robust zinc-organic framework with mixed nodes and its handy mixed-matrix membrane for highly effective luminescent detection of Fe3+, CrO42-, and Cr2O72- in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 1716–1725. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ding Y. J.; Zhao C. X.; Zhang P. C.; Chen Y. H.; Song W. W.; Liu G. L.; Liu Z. C.; Yun L.; Han R. Q. A novel quinoline derivative as dual chemosensor for selective sensing of Al3+ by fluorescent and Fe2+ by colorimetric methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1231, 129965. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.129965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang Q. Y.; Wong K. M. C. Photophysical, ion-sensing and biological properties of rhodamine-containing transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 416, 213336. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Paderni D.; Giorgi L.; Fusi V.; Formica M.; Ambrosi G.; Micheloni M. Chemical sensors for rare earth metal ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 429, 213639. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Yang J.; Yuan Z. L.; Yu G. Q.; He S. L.; Hu Q. H.; Wu Q.; Jiang B.; Wei G. Single chemosensor for double analytes: spectrophotometric sensing of Cu2+ and fluorogenic sensing of Al3+ under aqueous conditions[J]. J. Fluoresc. 2016, 26, 43–51. 10.1007/s10895-015-1710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Paisuwan W.; Lertpiriyasakulkit T.; Ruang pornvi-suti V.; Sukwattanasinitt M.; Ajavakom A. 8-Hydroxyjulolidine aldimine as a fluorescent sensor for the dual detection of Al3+ and Mg2+. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Res. 2020, 29, 100358. 10.1016/j.sbsr.2020.100358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang S. Q.; Zhang Y.; Zhao L. H.; Xu L. L.; Han H.; Huang Y. B.; Fei Q.; Sun Y.; Ma P. Y.; Song D. Q. A novel water-soluble near-infrared fluorescent probe for monitoring mitochondrial viscosity. Talanta 2021, 233, 122592. 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae T. D.; Schmidt P. J.; Pufahl R. A.; Culotta V. C.; O’Halloran T. V. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science 1999, 284, 805–808. 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Park G. J.; Na Y. J.; Jo H. Y.; Lee S. A.; Kim A. R.; Noh I.; Kim C. A single chemosensor for multiple analytes:fluorogenic detection of Zn2+ and OAc– ions in aqueous solution, and an application to bioima aging. New. J. Chem. 2014, 38, 2587–2594. 10.1039/C4NJ00191E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wu J. S.; Liu W. M.; Zhuang X. Q.; Wang F.; Wang P. F.; Tao S. L.; Zhang X. H.; Wu S. K.; Lee S. T. Fluorescence turn on of coumarin derivatives by metal cations: a new signaling mechanism based on C = N isomerization. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 33–36. 10.1021/ol062518z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Maity D.; Govindaraju T. Naphthaldehyde-urea/thiourea conjugates as turn-on fluorescent probes for Al3+ based on restricted C = N isomerization. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 5479–5485. 10.1002/ejic.201100772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen W. H.; Xing Y.; Pang Y. A highly selective pyrophosphate sensor based on ESIPT turn-on in water. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1362–1365. 10.1021/ol200054w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jang Y. K.; Nam U. C.; Kwon H. L.; Hwang I. H.; Kim C. A selective colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor based-on naphthol for detection of Al3+ and Cu2+. Dyes Pigm. 2013, 99, 6–13. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2013.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Jo T. G.; Na Y. J.; Lee J. J.; Lee M. M.; Lee S. Y.; Kim C. A multifunctional colorimetric chemosensor for cyanide and copper(II) ions. Sens. Actuators, B 2015, 211, 498–506. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.01.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Park G. J.; Park D. Y.; Park K. M.; Kim Y.; Kim S. J.; Chang P. S.; Kim C. Solvent-dependent chromogenic sensing for Cu2+ and fluorogenic sensing for Zn2+ and Al3+: a multifunctional chemosensor with dual-mode. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7429–7438. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Park G. J.; Hwang I. H.; Song E. J.; Kim H.; Kim C. A colorimetric and fluorescent sensor for sequential detection of copper ion and cyanide. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 2822–2828. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.02.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b You G. R.; Lee J. J.; Choi Y. W.; Lee S. Y.; Kim C. Experimental and theoreti-cal studies for sequential detection of copper(II) and cysteine by a colorimetric chemosensor. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 875–881. 10.1016/j.tet.2015.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gunnlaugsson T.; Leonard J. P.; Murray N. S. Highly selective colorimetric naked-eye Cu(II) detection using an azobenzene chemosensor. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1557–1560. 10.1021/ol0498951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Huang J.; Xu Y.; Qian X. A red-shift colorimetric and fluorescent sensor for Cu2+ in aqueous solution: unsymmetrical 4, 5-diaminonaphthalimide with NH deprotonation induced by metal ions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 1299–1303. 10.1039/b818611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pankaj A.; Tewari K.; Singh S.; Singh S. P. Waste candle soot derived nitrogen doped carbon dots based fluorescent sensor probe: An efficient and inexpensive route to determine Hg(II) and Fe(III) from water. J. Environ. Chem. Engin. 2018, 6, 5561–5569. 10.1016/j.jece.2018.08.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lee Y. J.; Lim C.; Suh H.; Song E. J.; Kim C. A multifunctional sensor: Chromogenic sensing for Mn2+ and fluorescent sensing for Zn2+ and Al3+. Sens. Actuators, B 2014, 201, 535–544. 10.1016/j.snb.2014.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mikata Y.; Yamashita A.; Kawamura A.; Konno H.; Miyamoto Y.; Tamotsu S. Bisquinoline-based fluorescent zinc sensors. Dalton Trans. 2009, 3800–3806. 10.1039/b820763a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu G. Q.; Cao Y. P.; Liu H. M.; Wu Q.; Hu Q. H.; Jiang B.; Yuan Z. L. A spirobenzopyran-based multifunctional chemosensor for the chromogenic sensing of Cu2+ and fluorescent sensing of hydrazine with practical applications. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 245, 803–814. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sudheer; Kumar V.; Kumar P.; Gupta R. Detection of Al3+ and Fe3+ ions by nitrobenzoxadiazole bearing pyridine-2, 6-dicarboxamide based chemosensors: Effect of solvents on detection. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 13285–13294. 10.1039/D0NJ00517G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Cao Y.-P.; Wu Q.; Hu Q.-H.; Yu G.-Q.; Yuan Z.-L. A sensitive probe for detection of Ca2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ based on schiff base derivative and application in bioimaging. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 49, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- a Baffi F.; Cardinale A. Improvements in use of Chelex-100 resin for determination of copper, cadmium and iron in sea water. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1990, 41, 15–20. 10.1080/03067319008030524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ryan D. K.; Weber J. H. Comparison of chelating agents immobilized on glass with chelex 100 for removal and preconcentration of trace copper (II). Talanta 1985, 32, 859–863. 10.1016/0039-9140(85)80198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Choi D. W.; Zea C. J.; Do Y. S.; Semrau J. D.; Antholine W. E.; Hargrove M. S.; Pohl N. L.; Boyd E. S.; Geesey G. G.; Hartsel S. C.; Shafe P. H.; McEllistrem M. T.; Kisting C. J.; Campbell D.; Rao V.; de la Mora A. M.; DiSpirito A. A. Spectral, kinetic, and thermodynamic properties of Cu (I) and Cu (II) binding by methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1442–1453. 10.1021/bi051815t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b López M. L.; Peralta-Videa J. R.; Benitez T.; Duarte-Gardea M.; Gardea-Torresdey J. L. Effects of lead, EDTA, and IAA on nutrient uptake by alfalfa plants. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 30, 1247–1261. 10.1080/01904160701555143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Qu X. F.; Yuan F. M.; He Z. Q.; Mai Y. H.; Gao J. M.; Li X. M.; Yang D. Z.; Cao Y. P.; Li X. F.; Yuan Z. L. A rhodamine-based single-molecular theranostic agent for multiplefunctionality tumor therapy. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 166, 72–83. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Mai Y. H.; Qu X. F.; Ding S. L.; Lv J. J.; Li X. M.; Gao P. Y.; Liu Y.; Yuan Z. L. Improved IR780 derivatives bearing morpholine group as tumor- targeted therapeutic agent for near-infrared fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 177, 107979. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.107979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Lv J. J.; Song W. T.; Li X. M.; Gao J. M.; Yuan Z. L. Synthesis of a new phenyl chlormethine-quinazoline derivative, a potential anti-cancer agent, induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma through mediating Sirt1/Caspase 3 signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 911. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.