Abstract

Objective:

To describe the methodological development and feasibility of real-world implementation of suicide risk screening into a pediatric primary care setting.

Methods:

A suicide risk screening quality improvement project (QIP) was implemented by medical leadership from a suburban-based pediatric (ages 12 to 25 years) primary care practice in collaboration with a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) suicide prevention research team. A pilot phase to acclimate office staff to screening procedures preceded data collection. A convenience sample of 271 pediatric medical outpatients was screened for suicide risk. Patients, their parents, and medical staff reported their experiences and opinions of the screening procedures.

Results:

Thirty-one (11.4%) patients screened positive for suicide risk, with one patient endorsing imminent suicide risk (3% of positive screens; 0.4% of total sample). Over half of the patients who screened positive reported a past suicide attempt. Most patients, parents, and medical staff supported the implementation of suicide risk screening procedures into standard care. A mental health clinical pathway for suicide risk screening in outpatient settings was developed to provide outpatient medical settings with guidance for screening.

Conclusions:

Screening for suicide risk in pediatric primary care is feasible and acceptable to patients, their families, and medical staff. A clinical pathway used as guidance for pediatric healthcare providers to implement screening programs can aid with efficiently detecting and managing patients who are at risk for suicide.

Keywords: suicide risk screening, pediatric primary care, mental health clinical pathway

Introduction

Over a quarter of all youth deaths in the US are from suicide, a preventable outcome.1 Youth who die by suicide are more than twice as likely to see a primary care clinician than a mental health specialist prior to death, with roughly 45% of young suicide decedents seeing a primary care clinician within 1 month of death by suicide.2–4 In February 2016, the main accreditation organization for U.S. hospitals, The Joint Commission, issued Sentinel Event Alert 56, encouraging U.S. hospitals and health care systems to screen both youth and adults for suicide risk in outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department (ED) settings.5

Primary care settings provide valuable opportunities to detect risk of suicide,6–9 yet most of these settings do not routinely screen for suicide risk.10 Screening for depression is more common in primary care settings, but studies show that depression screening may be inadequate for identifying patients at risk for suicide.11,12 Roughly half of pediatric primary care physicians have encountered at least one patient who attempted suicide in the past year.13 Barriers such as limited time, insufficient knowledge and training about suicide risk, discomfort with discussing suicide, concerns about iatrogenic risk, and uncertainty about managing patients who screen positive prevent successful integration of suicide risk screening into routine care.10,14–16 Moreover, it is not well documented how pediatric patients and their parents perceive suicide risk screening during a primary care visit. Without screening implementation guidelines and input from parents/guardians, primary care providers may be hesitant to screen patients for suicide risk and primary care settings may become overburdened by ineffective screening programs.

This quality improvement project (QIP) aimed to describe the real-world implementation of suicide risk screening in a pediatric primary care setting. Feasibility was assessed in the following domains:

Acceptability – do clinic staff, parents and patients find screening acceptable?

Disruptiveness – based on staff report, does screening interfere with normal workflow?

Positive screen prevalence rate – is the positive screen rate common enough to warrant screening (i.e., a study of a large sample of hospital patients aged 12 to 17 years old universally screened for suicide risk reported positive screen rates ranging from 2.1%−8.5%17 or the ASQ validation studies which found a screen positive rate of 14% in an adolescent health clinic18 and 13.5% on an inpatient medical/surgical unit19)?

A secondary aim was to use results from the implementation to develop an evidence-informed mental health clinical pathway to guide future suicide risk screening programs in outpatient medical settings.

Methods

In May 2015, the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) research team at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) established a collaboration with a primary care pediatric practice to study the integration of suicide risk screening and the development of operating procedures into a pediatric practice’s standard of care. The lead senior physician and nurse leader, championed the QIP utilizing a multi-cycle, iterative “plan-do-study-act” approach20 which was carried out in four phases over a period of 11 months. For example, it was decided that the screen would be administered when the nurse was finished assessing vital signs. In that way, the screen could be scored with enough time to contact the physicians in advance of the physical exam. The NIMH ASQ team observed and provided consultation at bi-weekly meetings. This process sought to balance burden on staff while allowing regular opportunities for feedback.21

Setting & Population

Participants were a convenience sample of all patients ages 12 to 25 years who presented for well visits over approximately five months from one clinic of a pediatric primary care outpatient multisite practice in a suburb of Richmond, Virginia. The designated clinic was known as early adopters of other quality improvement processes. The QIP began one cycle with patients presenting for well visits only, but once nurses were comfortable, another cycle of the QI process expanded to include sick visits as well. Exclusion criteria included being under the age of 12 years old and presenting to the practice without a parent/legal guardian (hereafter referred to as “parent”). Nurses were permitted to use their clinical judgment to override the age exclusion criteria to screen patients as young as 8 years who presented with a mental health concern and were accompanied by a parent. The QIP was determined to be exempt from IRB review by the NIH Office of Human Subjects Research.

Phase 1: Plan

During the initial planning of the QIP, the practice decided to use the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)22 as their screening tool of choice due to its brevity and validity among pediatric medical patients.

A suicide risk screening program was designed utilizing the practice’s workflow in combination with the NIMH ASQ team’s implementation experience. Flyers were modified from the ASQ toolkit (www.nimh.nih.gov/ASQ) and disseminated to patients and parents when registering at the front desk. After obtaining vital signs, nurses verbally screened all patients ages 12 and older for suicide risk and depression without the parent in the room and reviewed the results independently in real time to determine whether the patient screened positive. In this portion of the QIP, nurses were trained to ask the questions verbally in line with previous ASQ research;22 however, the ASQ is administered by some medical settings via self-report. Nurses notified pediatricians before the pediatrician entered the exam room if their patient screened positive. Pediatricians were trained to conduct a brief suicide safety assessment (BSSA) to determine the patient’s level of risk and discharge disposition. If the patient was found to be at risk for suicide, they discussed with the patient that parents would be told about their safety concerns so that they could partner in keeping the child safe. As a safety net process to optimize safety, before implementation began, the practice contacted a local mental health provider who agreed to evaluate patients that screened positive for suicide risk within 72 hours.

Phase 2: Do

Staff Training and Baseline Staff Feedback Prior to ASQ Implementation

In September 2015, the staff attended an in-person training session led by the NIMH ASQ team. Before the training, staff completed a pre-training knowledge questionnaire as well as a survey gauging their opinions of suicide risk screening. The training session included an overview of the epidemiology of youth suicide with a focus on medical settings, The Joint Commission recommendations for screening, clinical warning signs/risk factors, QIP aims, safety planning and how to initiate lethal means safety counseling (an evidence-based process of helping patients and their support system safely store or remove potentially dangerous items that could be used in a suicide attempt (e.g. firearms, knives, pills, etc.).23 Staff were trained on how to administer the ASQ, interpret the screening results, and respond when a patient screened positive. Local and national suicide risk resources were provided for use in the referral process. After the training and before implementation, staff completed the same knowledge questionnaire to assess if scores improved after the training.

Training for Providers to Manage Positive Screens

The NIMH ASQ team trained pediatricians, during a two hour in-person workshop in the practice, to conduct brief 10–15-minute suicide safety assessments to efficiently manage each patient and determine an appropriate disposition. Pediatricians were instructed in how to assess important details of suicide risk, including frequency and severity of suicidal thoughts, the presence of a suicide attempt plan and other psychosocial stressors and protective factors. Pediatricians were trained to interview the patient separately and together with the parents, develop a safety plan, and determine an appropriate disposition. Four disposition outcomes were possible: 1) immediate referral to the emergency department (ED) for a psychiatric evaluation, 2) referral to outpatient mental health services within 72 hours for a full mental health evaluation, 3) non-urgent referral to outpatient services, or 4) no further intervention necessary. The plan for identifying imminent risk was to truncate the well visit and send the patient to the ED via a parent or emergency transport services.

Screening Pilot Phase

After all staff were trained, a 4-month pilot screening phase between November 2015 and February 2016 was implemented during well visits to identify unanticipated barriers and process improvement opportunities. The NIMH ASQ team had bi-weekly conference calls with clinic staff to continuously review the screening process and troubleshoot problems. For example, a few parents were concerned about whether asking young people questions about suicide would make them suicidal. When this was discussed, the ASQ team designed a flyer that announced the screening and why it was important. Additionally, four research studies refuting the myth of iatrogenic risk were placed into a binder that was kept at the front desk and made available to any parent that wanted more information.

Phase 3: Study

In February 2016, members of the NIMH ASQ team conducted in-person, twenty-minute one-on-one interviews with staff to obtain staff opinions of the pilot phase. Staff gave input on challenges associated with the screening program and offered suggestions for any changes they thought would improve the screening workflow. Staff also participated in a 1-hour booster training session in which results and lessons learned from the QIP were presented and the office screening procedures were reviewed.

Phase 4: Act

During the Act phase (February to June), the nurses screened all patients ages 12 and older presenting for well visits, as the annual physical or check-up would allow more time for administering the suicide risk screen. Feedback surveys were then completed by patients and parents. A concluding debriefing between the NIMH ASQ team and the practice leadership took place in June 2016 to discuss final thoughts and address additional adjustments that would enhance their screening program.

Post-Implementation Follow-Up

In January 2019, the NIMH ASQ team sent a final set of feedback surveys to the practice staff to examine the state of screening in the office after several years.

Measures

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions –

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)22 is a validated 4-item brief screening questionnaire developed in the ED, but now empirically validated in all medical settings, to assess suicidal ideation and behavior in pediatric medical patients ages 10 and above; recommended for age 8 and above for patients who present with psychiatric chief complaints. An affirmative response to any of the four items prompts a fifth acuity item to assess current suicidal ideation. Patients who screen positive and do not endorse the acuity item are categorized as a non-acute positive screen. Patients who endorse the acuity item are considered an acute positive screen. A negative response to all items is a negative screen. The ASQ has a sensitivity of 96.9%, a specificity of 87.6%, and a negative predictive value of 99.7% for pediatric medical patients.22 The ASQ has since been validated in other pediatric medical settings, including outpatient primary care and specialty clinics and inpatient medical/surgical units, as well as for adult medical patients.18,19,22,24 The ASQ takes, on average, 20 seconds to administer.

Patient Demographic Information –

Formal demographic questionnaires were not completed by patients. Instead, nurses accessed the patients’ sex, age and race from their medical chart and noted the demographic information on the patients’ ASQ form.

Patient and Parent Surveys –

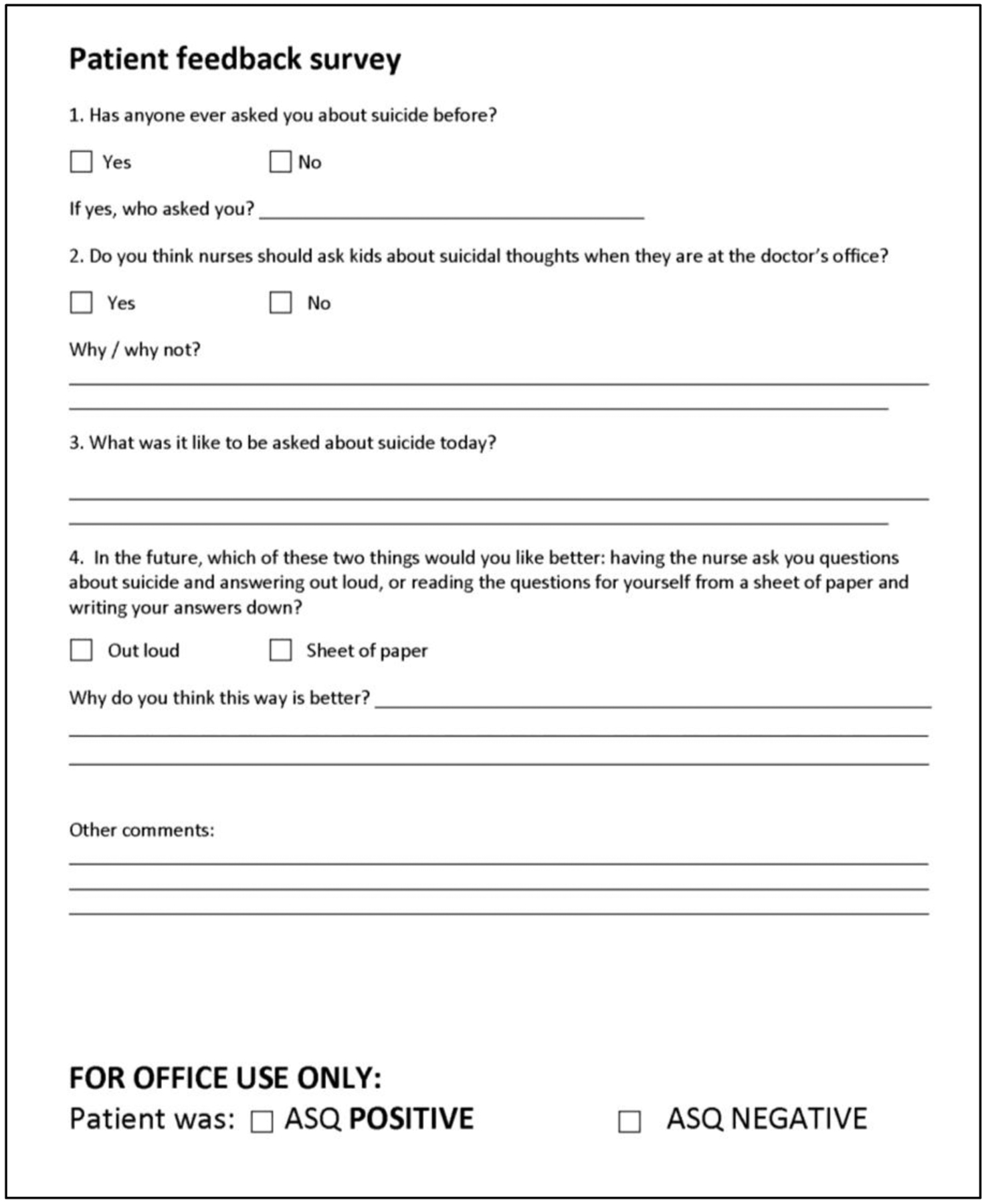

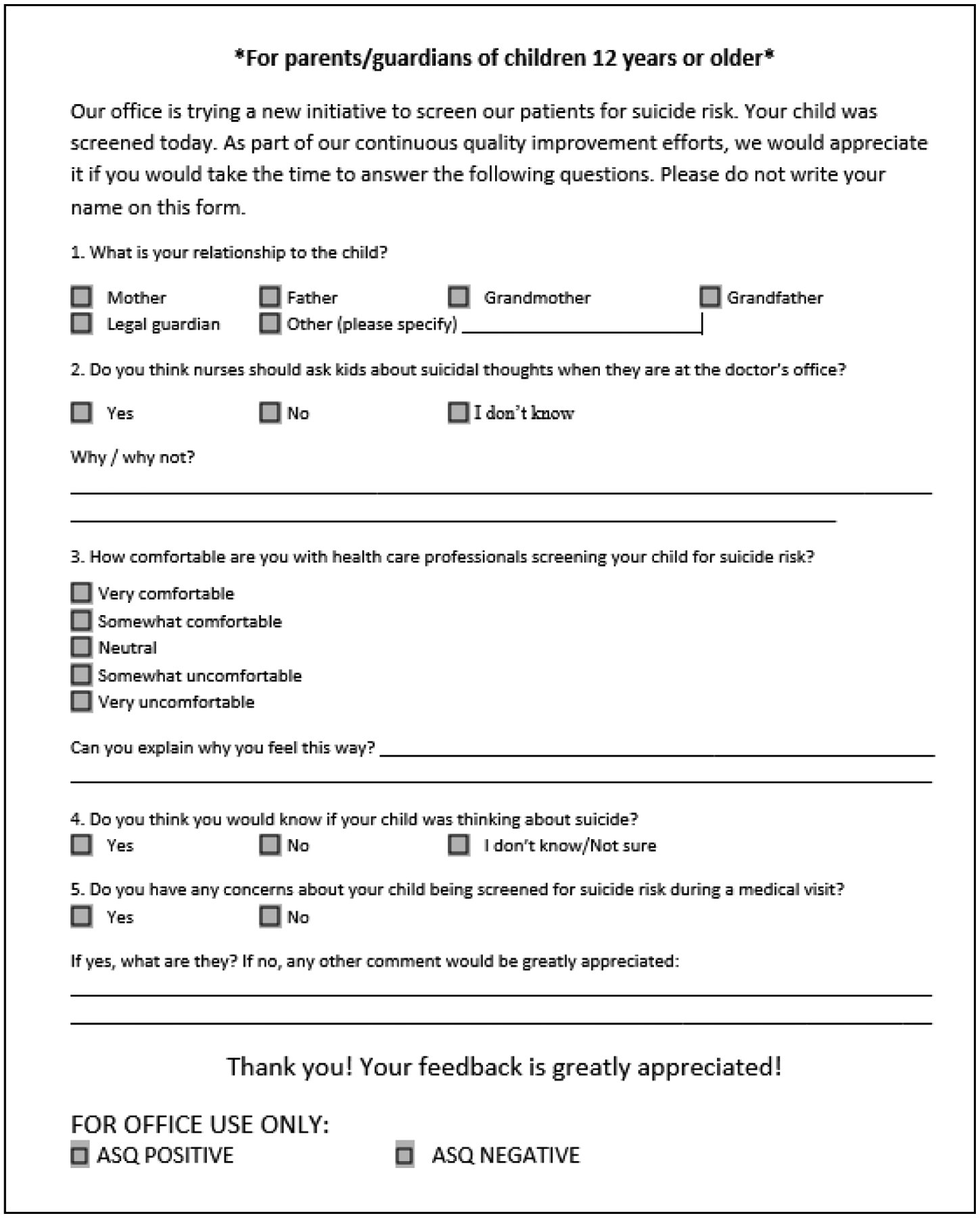

After completing the ASQ, patients answered a 5-item self-report paper/pencil evaluation questions based on their experience of being screened for suicide risk (Figure 1). Parents completed a similar self-report paper/pencil questionnaire in the waiting room about their opinions of suicide risk screening at the pediatrician’s office (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Patient Feedback Survey administered to patients after ASQ screening

Figure 2.

Parent Feedback Survey administered to parents of patients screened with the ASQ

Clinic Staff Questionnaires -

Nurses and pediatricians completed a 15-item self-report suicide prevention questionnaire measuring their knowledge of youth suicide immediately before and directly after the initial training session. Staff also completed feedback surveys on their own comfort screening and managing suicide risk at two timepoints: after an initial training session during Phase 2 and after the final data collection was completed.

Data Analysis

Data from the ASQ questionnaires and all feedback surveys were analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics were calculated and a repeated sample t-test was performed to compare staff performance on the knowledge questionnaires before and after the initial training sessions.

Results

A total of 273 patients were screened during data collection. Of those, 271 patients completed both the ASQ and the Patient Feedback Survey and were included in this analysis. Complete demographic data were not available for all patients (see Table 1), due mainly to nursing omission. The sample was predominantly female (114/211; 54%) and White (146/181; 80%), ranging in age from 12 to 25, with an average age of 15.1 years (n=227; SD = 2.17). The parent feedback form was completed by 248 parents. Twenty-three patients did not have parent survey data and 16 of these patients were aged 18 years old or older and did not come with a parent to the visit. Demographic data were not collected for parents.

Table 1:

Sample Demographic and Suicide Risk Screening Characteristics

| Patient Characteristics | Total Sample (n=271) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (Mean, SD) | 15.1 years (2.17) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 114 | 42.07% |

| Male | 97 | 35.79% |

| Unknown | 60 | 22.14% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 146 | 53.87% |

| Black/African American | 26 | 9.60% |

| Asian American | 6 | 2.21% |

| Other | 3 | 1.11% |

| Unknown | 90 | 33.21% |

| Patient Characteristics of Positive Screens | Total Sample (n=31) | |

| Age in years (Mean, SD) | 15.1 years (2.31)* | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 15 | 48% |

| Male | 9 | 29% |

| Unknown | 7 | 23% |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 18 | 54% |

| Black/African American | 2 | 10% |

| Asian American | 1 | 2% |

| Other | 0 | 0% |

| Unknown | 10 | 33% |

| ASQ Items | Items Indorsed (n=31) | Percentage |

| #1: In the past few weeks, have you wished | 14 | 45.16% |

| #2: In the past few weeks, have you felt | 9 | 29.03% |

| #3: In the past week, have you been having | 6 | 19.35% |

| #4: Have you ever tried to kill yourself? | 17 | 55.84% |

| #5: Are you having thoughts of killing | 1 | 3.23% |

| Suicide Attempt Method | Total Attempts Reported (n=22) | |

| Poisoning | 10 | 45% |

| Suffocation | 4 | 18% |

| Cutting/Piercing | 4 | 18% |

| Struck By/Against | 2 | 9% |

| Falling | 1 | 5% |

| Method Not Disclosed | 1 | 5% |

Age was only available for 29 patients

Suicide Risk Screening Prevalence Rate

Out of the 271 patients who completed the ASQ, 31 (11.4%) screened positive for suicide risk. Of these 31 patients, 30 screened “non-acute” positive (97% of positive screens; 11% of total sample) and 1 patient screened “acute” positive (3% of positive screens; 0.4% of total sample), indicating imminent suicide risk. Over half of the patients who screened positive reported a past suicide attempt (17/31; 55%). Of the 31 patients who screened positive, 14 (45%) were positive based on a sole “yes” to the past suicide attempt item (Q4 on the ASQ). Table 1 reports more information regarding demographics of patients who screened positive and reported suicide attempt history.

Patient Feedback about Screening

Overall, 64% (175/271) of patients reported they had never been asked about suicide previously. Grouped by level of suicide risk, 70% (168/240) of patients who screened negative and 22% (7/31) of patients who screened positive had never been asked about suicide, including the patient who screened “acute” positive. Most patients (247/271; 91%) reported opinions that nurses should ask kids about suicide risk in the doctor’s office. The one patient who was at imminent risk for suicide reported, “I would not have told anyone [if I wasn’t asked]”. Among the minority of patients that were not in favor, reasons given included concern over iatrogenic risk “it will make kids think about suicide.” Although nurses verbally administered the ASQ to all patients in this QIP, approximately half of all patients (134/271; 49%) indicated they would prefer completing a written version of the ASQ if given the option, whereas 40% (108/271) indicated they preferred verbally answering the questions. Eight percent (23/271) had no preference and 3% (9/271) of responses were missing. Patients who screened positive answered similarly: 48% (15/31) preferred paper, 32% (10/31) preferred answering verbally, 16% (5/31) had no preference, and one patient had missing data.

Parent Feedback about Screening

Parent feedback forms were collected from 248 parents (91.5%) of the 271 patients screened. Most parent feedback forms were completed by mothers (199/248; 80%). Seventy-four percent (185/248) of parents reported that nurses should screen kids for suicide risk in the doctor’s office, with one parent stating, “Kids feel comfortable at the doctor’s office.” A portion of parents, 16% (41/248), reported they were “not sure,” and 8% (20/248) did not think nurses should screen for suicide risk (1% (2/248) did not respond). Parents not in favor of screening reported concerns over mixing physical and mental health, “The child is [at the doctor’s office] to fix a physical ailment.” Eighty percent (199/248) of parents reported being “somewhat” or “very” comfortable with their child being screened and 6% (16/248) of parents reported being “somewhat” or “very” uncomfortable with their child being screened. The remaining 13% (33/248) of parents were “neutral”. When asked specifically if they had concerns about screening, most parents (218/248; 88%) reported that they had none.

Feedback Surveys from Staff

Phase 2 began with administering feedback surveys to the staff. All pediatricians (3) and nurses (11) completed the staff feedback survey before the NIMH training. Almost all pediatricians (2/3) and nurses (10/11) reported being “comfortable” or “very comfortable” working with patients who had thoughts of suicide and asking patients about past and current suicidal ideation. All three pediatricians and most nurses (73%; 8/11) agreed that clinicians should ask patients about suicide risk in the medical setting. Twelve staff members also completed both a pre- and post-training knowledge questionnaire. There was a statistically significant increase in total scores on the knowledge survey between the pre- and post-knowledge surveys, with higher scores indicating more correct answers (t(22)=3.27, p = 0.003).

During Phase 3, five nurses and five pediatricians participated in one-on-one interviews. All nurses reported that initially the hardest part of the screening program was administering the ASQ to pediatric patients due to their own discomfort about asking direct questions about suicide. Nurses further reported that after a few patients revealed past suicidal ideations and/or attempts, they better understood the importance of screening young people in medical settings. Multiple pediatricians stated that starting the QIP with a short pilot was helpful to acclimate the staff to the new screening program. No specific changes were suggested by staff during the interviews.

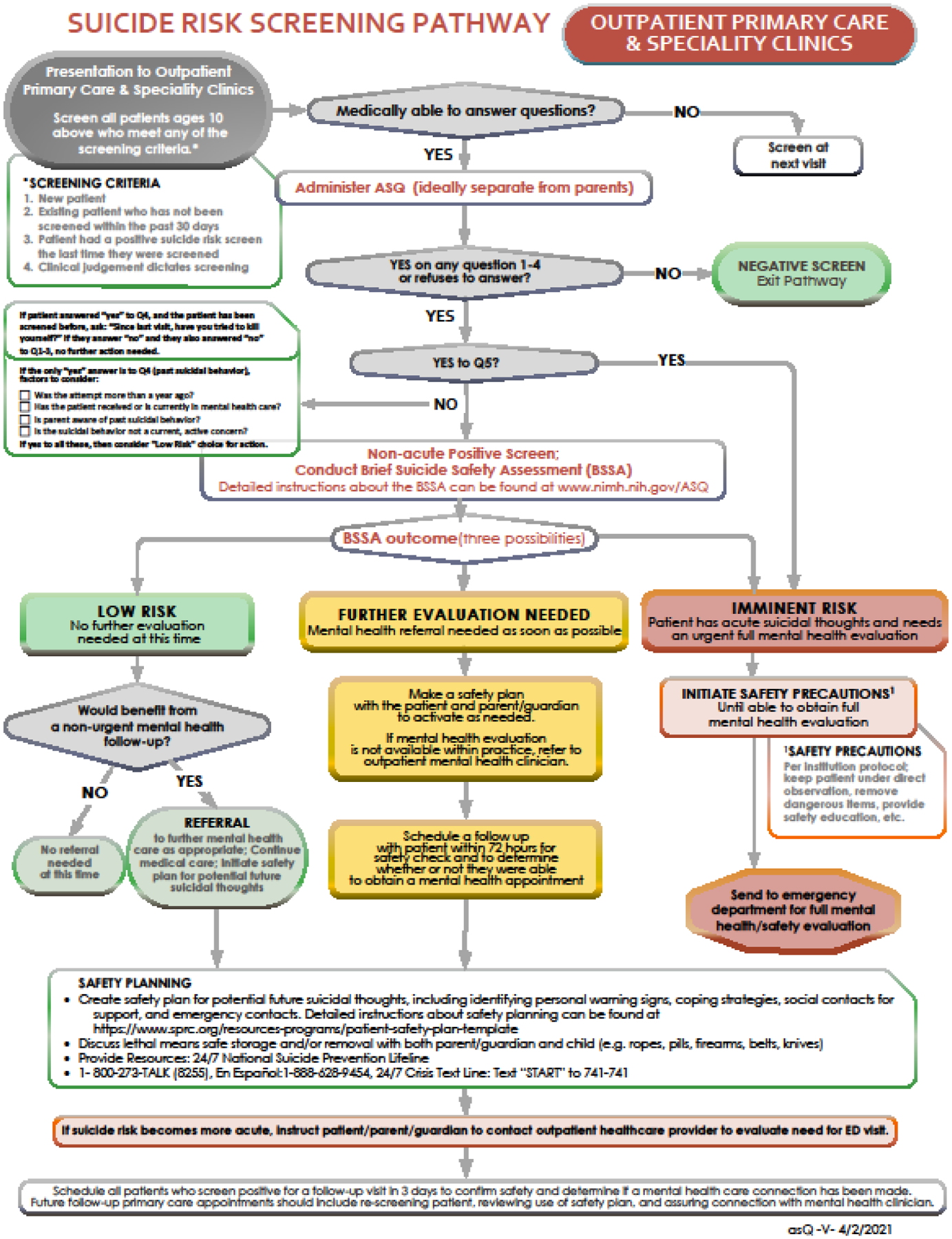

A final debriefing meeting between the practice’s leadership and NIMH ASQ team occurred during Phase 4 in June 2016 to determine how the practice would continue screening. Staff informed the NIMH ASQ team that they were ready to screen all patients beginning at age 10 years during all visits, including sick visits. Since they wanted to begin screening for depression, and they could screen for both suicide risk and depression as self-report measures in the waiting room, a document which included the PHQ-A (Johnson et al., 2002) and ASQ on a single page was created for all patients to complete on their own to improve efficiency (available on the ASQ Toolkit: www.nimh.nih.gov/ASQ) at the request of the office staff. A youth suicide risk clinical pathway for outpatient pediatricians was adapted from ED and inpatient clinical pathways25 and modeled with input from these data and other outpatient clinics (see Figure 3). This pathway was further reviewed and updated by expert pediatricians.

Figure 3:

Pediatric Outpatient Suicide Risk Screening Clinical Pathway

Following the implementation of screening as standard practice at all visits for youth ages 10 years and older during Phase 4 in June 2016, eight pediatricians and seven nurses completed post-implementation feedback surveys. Most nurses (5/7; 71%) reported that screening was not disruptive to their office workflow, they were comfortable with screening patients for suicide risk (5/7; 71%), and they felt prepared to screen patients for suicide risk (6/7; 86%). When asked about the impact of the QIP in their clinic, multiple nurses felt that the screening helped identify patients whose mental health concerns would otherwise have been undetected. For example, one nurse stated: “I believe we have saved some patients” and another said: “We have stopped some kids from doing something tragic.”

Most pediatricians (6/8; 75%) who provided post-implementation feedback reported that screening was not disruptive to their office workflow. All pediatricians reported being comfortable with and prepared for the management of patients who screened positive. Most pediatricians (5/8; 62%) reported interest in more training to manage patients at risk for suicide, with each of these pediatricians emphasizing the importance of continuing education on this topic.

Discussion

The results from this QIP support universal suicide risk screening in pediatric primary care practices. Results demonstrate that screening is acceptable to most patients, parents, and staff, is feasible to implement, and is non-disruptive to current office workflow. Support from office leadership, adequate planning and training utilizing a QIP framework, and frequent self-monitoring to make real-time improvements were essential for the success of this implementation.

Medical staff reported that trainings and a brief pilot phase were critical to alleviating trepidation about talking to young patients about suicide. Outpatient pediatric practices that plan to implement suicide risk screening programs may benefit from a gradual adoption of screening methods that allow for real-time program adjustments. Furthermore, as most nurses reported being comfortable with screening within a month, medical settings may find that staff are able to quickly acclimate to asking patients about suicide, particularly with adequate training specifically around safety planning.

Creating a connection with mental health providers before screening was implemented was another critical step in the successful functioning of this screening program. All patients that screened positive and were not already in mental health care, but required further evaluation were referred to the psychologist who had an a priori agreement to evaluate this practice’s positive screens. Outpatient practices that start to screen their patients for suicide risk may benefit from creating connections with outpatient mental health services, including community clinics or telehealth services, to provide their patients with appropriate mental health follow up care. Establishing a roadmap for follow-up care is a crucial step in the success of implementation.21 Pediatric providers that do not have access to such resources can schedule follow-up appointments or utilize tele-health services with patients at risk for suicide within 72 hours to follow-up on the patients’ well-being.

The observed screen positive rate of 11.4% was high enough to warrant screening yet, according to staff report, was not overly burdensome, amounting to approximately one additional mental health referral per week. The screen positive rate was higher than in other outpatient clinics (2.2%)17 possibly due to the patient age in this clinic ranging up to 25 years old; older teens and young adults have higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. These data support other findings that patients presenting with medical chief complaints will only rarely screen positive for imminent risk for suicide.16,26 Only one patient in this practice endorsed acute suicidal thoughts, comprising less than 0.4% of all screens. Consistent with national data, most youth (55.8%) who screened positive in this sample also reported a history of suicide attempts. Previous studies have identified that the most potent risk factor for death by suicide is a previous attempt.27 Identifying these higher risk patients and reviewing a safety plan that includes lethal means safety planning could reduce the likelihood of a future suicide attempt.

Lessons learned from this suicide risk screening QIP implementation informed the development of a mental health clinical pathway for screening in outpatient primary care settings (see Figure 3). The proposed outpatient clinical pathway was modeled after a 3-tiered system pathway for ED and inpatient medical/surgical units created by the Pathways in Clinical Care (PaCC) workgroup from within the Physically Ill Child committee of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP).25 The three tiers of the outpatient pathway consist first of a brief, 20 second screen with the ASQ, followed by a brief suicide safety assessment using either the ASQ BSSA (www.nimh.nih.gov/ASQ) or the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)28 to determine next steps. The use of a BSSA as the second step is critical to help the pediatrician more efficiently decide on one of four choices for disposition: 1) refer to emergency services, 2) urgent outpatient mental health services as soon as possible, 3) non-urgent outpatient services or 4) no further interventions. The outpatient clinical pathway serves as an evidence-informed template to allow any outpatient medical setting to adapt the guidelines depending upon their available staff and resources. This pathway was also modified for virtual telehealth administration.29

The following limitations should be taken into consideration. First, the use of self-report measures limited our ability to determine the risk status of patients who did not disclose their recent suicidal ideations or past attempts. Moreover, favorable opinions of screening may have been biased towards more positive responses; however, these data are in line with other ASQ studies that have shown favorable opinions of screening in other medical settings.30,31 Second, these data represent suicide risk screening implementation, but no disposition outcomes were available. Third, due to the focus on well visits, this sample may not be representative of the full spectrum of outpatients who present to a primary care practice, and is focused on one clinic, thereby limiting generalizability. It should also be noted that this practice was chosen among a practice of multisite clinics because they were known for being early adopters of other QIP efforts, which may account for the higher ratings of comfort with screening prior to the training. Staff comfort with training may typically be lower prior to gaining more experience working with suicidal patients. Additionally, more quantitative measures of disruptiveness, such as duration of visit or missed opportunities for other health screenings, would be useful in future studies. The modality of asking for verbal responses to screening (versus obtaining written responses) should undergo further study. Finally, a portion of demographic data was not recorded, limiting the ability to look more in depth at how suicide risk varies by factors such as gender and race. Further research should continue studying implementations of suicide risk screening in primary care practices across the country, particularly in rural and underserved communities, to determine the feasibility of screening programs in those outpatient medical settings.

Pediatric healthcare providers on the frontlines of the national youth suicide public health crisis can feasibly implement universal suicide risk screening. Suicide risk screening in medical settings, such as this clinic, provides the opportunity for early identification of youth at risk, a critical suicide prevention strategy. Quality improvement practices and evidence-informed guidance for screening can preserve resources and provide pediatricians with the tools they need to intervene and save young lives.

What’s New.

Pediatric providers on the frontlines lack guidance to address increasing youth suicide rates. A novel outpatient suicide risk clinical pathway was created to assist pediatric primary care providers in feasibly implementing suicide risk screening and management of patients at risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeanne Radcliffe, Nathan Lowry, Brian Kurtz, Khalid Afzal, Lisa Giles, Elizabeth Kowal, Kyle Johnson, Sigita Plioplys, and the PaCC Workgroup. The authors would also like to thank the patients, parents, pediatricians, and nurses at the Pediatric & Adolescent Health Partners primary care office for their participation.

Financial acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (ZIAMH002922).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death reports, 1981–2017. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcause.html

- 2.LeFevre ML, Force USPST. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. May 20 2014;160(10):719–26. doi: 10.7326/M14-0589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDowell AK, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Practical suicide-risk management for the busy primary care physician. Mayo Clin Proc. Aug 2011;86(8):792–800. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. May 21 2013;158(10):741–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert 56: detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. 2016. [PubMed]

- 6.Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent primary care visit patterns. Ann Fam Med. Nov-Dec 2010;8(6):511–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowitz LM, Ballard ED, Pao M. Suicide screening in schools, primary care and emergency departments. Curr Opin Pediatr. Oct 2009;21(5):620–7. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283307a89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon JA, Avenevoli S, Pearson JL. Suicide Prevention Research Priorities in Health Care. JAMA Psychiatry. Sep 1 2020;77(9):885–886. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarin A, Conners GP, Sullivant S, et al. Academic Medical Center Visits by Adolescents Preceding Emergency Department Care for Suicidal Ideation or Suicide Attempt. Acad Pediatr. Sep-Oct 2021;21(7):1218–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond GS, O’Malley A, Wintersteen MB, et al. Attitudes, practices, and barriers to adolescent suicide and mental health screening: a survey of pennsylvania primary care providers. J Prim Care Community Health. Jan 1 2012;3(1):29–35. doi: 10.1177/2150131911417878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz LM, Mournet AM, Lanzillo E, et al. Screening Pediatric Medical Patients for Suicide Risk: Is Depression Screening Enough? J Adolesc Health. Jun 2021;68(6):1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemper AR, Hostutler CA, Beck K, Fontanella CA, Bridge JA. Depression and Suicide-Risk Screening Results in Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatrics. Jul 2021;148(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-049999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankenfield DL, Keyl PM, Gielen A, Wissow LS, Werthamer L, Baker SP. Adolescent patients--healthy or hurting? Missed opportunities to screen for suicide risk in the primary care setting. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Feb 2000;154(2):162–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.2.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Pao M, Boudreaux ED. Screening youth for suicide risk in medical settings: time to ask questions. Am J Prev Med. Sep 2014;47(3 Suppl 2):S170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFaul MB, Mohatt NV, DeHay TL. Development, evaluation, and refinement of the Suicide Prevention Toolkit for Rural Primary Care Practices. Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2014;38(2):116–127. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wintersteen MB. Standardized screening for suicidal adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. May 2010;125(5):938–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roaten K, Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, et al. Universal Pediatric Suicide Risk Screening in a Health Care System: 90,000 Patient Encounters. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. Jul-Aug 2021;62(4):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2020.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguinaldo LD, Sullivant S, Lanzillo EC, et al. Validation of the ask suicide-screening questions (ASQ) with youth in outpatient specialty and primary care clinics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Jan-Feb 2021;68:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horowitz LM, Wharff EA, Mournet AM, et al. Validation and Feasibility of the ASQ Among Pediatric Medical and Surgical Inpatients. Hosp Pediatr. Sep 2020;10(9):750–757. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deming WE. The New Economics for Industry, Government, Education. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. Aug 7 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, et al. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Dec 2012;166(12):1170–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety Planning Intervention: A Brief Intervention to Mitigate Suicide Risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012/May/01/ 2012;19(2):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horowitz LM, Snyder DJ, Boudreaux ED, et al. Validation of the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions for Adult Medical Inpatients: A Brief Tool for All Ages. Psychosomatics. Nov - Dec 2020;61(6):713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brahmbhatt K, Kurtz BP, Afzal KI, et al. Suicide Risk Screening in Pediatric Hospitals: Clinical Pathways to Address a Global Health Crisis. Psychosomatics. Jan - Feb 2019;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyder DJ, Jordan BA, Aizvera J, et al. From Pilot to Practice: Implementation of a Suicide Risk Screening Program in Hospitalized Medical Patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. Jul 2020;46(7):417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha CB, Franz PJ, E MG, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Annual Research Review: Suicide among youth - epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Apr 2018;59(4):460–482. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. Dec 2011;168(12):1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pao M, Mournet AM, Horowitz LM. Implementation challenges of universal suicide risk screening in adult patients in general medical and surgical settings. 2020;37(7):25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard ED, Stanley IH, Horowitz LM, Pao M, Cannon EA, Bridge JA. Asking Youth Questions About Suicide Risk in the Pediatric Emergency Department: Results From a Qualitative Analysis of Patient Opinions. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. Mar 2013;14(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpem.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross AM, White E, Powell D, Nelson S, Horowitz L, Wharff E. To Ask or Not to Ask? Opinions of Pediatric Medical Inpatients about Suicide Risk Screening in the Hospital. J Pediatr. Mar 2016;170:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]