Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Pediatric growth tracking has been identified as a top priority by international health agencies to assess the severity of malnutrition and stunting. However, remote low-resource settings often lack the necessary infrastructure for longitudinal analysis of growth for the purposes of early identification and immediate intervention of stunting.

METHODS:

To address this gap, we developed a portable field unit (PFU) capable of identifying a child over the course of multiple visits, each time adding new anthropomorphic measurements. We conducted a preliminary field evaluation of the PFU by using the unit on two distinct visits to three schools in the area surrounding a medical clinic in rural San Jose, Honduras. The unit was used to assess children at each school as part of the community outreach.

RESULTS:

Community outreaches to three schools were conducted by two distinct teams, where they used the device to assess 210 children. Of the 180 children registered during the first visit, 112 were re-identified and assessed on the subsequent visit. Twenty-four instances of moderate-to-severe malnutrition were identified and referred for further evaluation to the central clinic.

CONCLUSION:

This initial assessment suggests that the PFU could be an effective means of identifying at-risk children.

Keywords: pediatrics, Honduras, clinical decision support, growth tracking, stunting

Abstract

CONTEXTE :

Les organismes internationaux de santé ont identifié le suivi de la croissance des enfants comme une priorité absolue pour évaluer la gravité de la malnutrition et les retards de croissance. Cependant, les zones reculées à faibles ressources n’ont souvent pas les infrastructures nécessaires à l’analyse longitudinale de la croissance à des fins d’identification précoce et d’intervention immédiate de lutte contre les retards de croissance.

MÉTHODES :

Pour combler ces lacunes, nous avons développé un appareil portatif de terrain (PFU) capable d’identifier un même enfant lors de plusieurs visites et d’ajouter les nouvelles mesures anthropomorphiques de chaque visite. Nous avons réalisé une évaluation de terrain préliminaire du PFU en utilisant l’appareil lors de deux visites différentes dans trois écoles de la zone rurale aux alentours d’une clinique médicale de San Jose, Honduras. L’appareil a été utilisé pour évaluer les enfants de chaque école dans le cadre d’un programme de sensibilisation communautaire.

RÉSULTATS :

Des programmes de sensibilisation communautaire ont été menés dans trois écoles par deux équipes différentes, qui ont utilisé l’appareil pour évaluer 210 enfants. Sur les 180 enfants enregistrés lors de la première visite, 112 ont été de nouveau identifiés et évalués lors de la visite suivante. Vingt-quatre cas de malnutrition modérée à sévère ont été identifiés et adressés pour examen complémentaire à la clinique centrale.

CONCLUSION :

Cette évaluation initiale suggère que le PFU pourrait être un moyen efficace d’identification des enfants à risque.

Malnutrition is a measurable decline in health due to an excess, imbalance, or deficiency of nutrients in the body.1,2 It is estimated that nearly 2 billion people in the world suffer from some form of malnutrition, which could have long-term health and economic consequences, such as physical and cognitive stunting, severe illness, chronic disease, and decreased worker productivity.3–5 The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that roughly 3.5 trillion US dollars (USD) are lost per year in the global economy as a result of under and overnutrition.3 Early identification of signs of malnutrition, followed by intervention, is essential to avoid both short- and long-term impacts of malnutrition. This is especially true for children, as malnutrition and infection in early life increase the risk of chronic non-communicable diseases in later life.6

Pediatric growth monitoring can be used to identify children at risk of deviating from their trend lines before long-term consequences occur. The WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have both identified pediatric growth tracking as a top priority and developed standard growth charts.7 The 2006 WHO growth chart is an international growth standard for describing child growth in optimal conditions and can be used to identify children whose measurements indicate malnutrition.

Honduras, a low-income Central American country, has made significant progress toward reducing the burden of moderate-to-severe nutritional deficiencies (as measured by weight-for-age) from 24.3% in 1996 to 11.4% in 2005–2006.8 The difficulty with further improving this statistic is due to poverty and a lack of basic services in large parts of the country. A calculation of unmet basic needs in 2013 found that 15.9% of Hondurans were either living in extreme poverty or were unable to provide for their own or for their dependents’ food, clothing, housing, and healthcare due to lack of income or resources.9 On a national level, Honduras has no formal electronic health record (EHR) system to use as a repository for patient demographics and vitals. The creation of an EHR is understandably not a primary focus, as 87% of hospitals do not have the daily supplies needed, 53% have deficient facilities, and 50% do not have the minimum medical equipment required for operation.8

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Shadyside Family Medicine Residency Program has partnered with Shoulder to Shoulder Pittsburgh/San Jose, a non-governmental organization in San Jose, Honduras, and its US counterpart in Pittsburgh, PA, USA, to provide care to rural communities. Using anecdotal evidence, local health workers in the community identified malnutrition and stunting as ongoing in the catchment population. Numerous interventions targeting malnutrition were implemented using a community-based primary care model. The first intervention was a collaboration with a Honduran NGO, Projecto Mama, that provided locally produced soy-based nutritional biscuit supplement. This was followed by the distribution of chispuditos, a soy micronutrient supplement.10,11 Further community input led to the implementation of a nutrition program to provide eggs to both mother and child for the first 1,000 days of life. However, in the absence of a formal structure for tracking stunting over time, it was impossible to gauge the effectiveness of these longitudinally.

Studies conducted worldwide have shown the potential impact of growth tracking in rural communities, although each study has implemented this work differently. Work done in rural South Africa used a community-based approach relying on individual households to collect handwritten records; Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda have all employed coalitions of community health workers to track growth and provide nutritional counseling in a similar fashion.12 While many existing interventions focused on the process of collecting information, interpreting a growth chart, and providing medical advice to evaluate a child’s response, none of the reviewed studies propose a feasible electronic system capable of storing this information. Pediatric-focused EHRs like iPediatric EHR exist, although these are rarely capable of running portably; and, those that do work portably, lack the ability to run offline and would not be able to withstand harsh environments.13

The aim of this project was to develop a device capable of monitoring children in rural Honduras over time for stunting, wasting, and obesity, by adding new anthropomorphic measurements during each visit, and providing a longitudinal analysis of growth for the purposes of early detection and intervention planning. With no existing infrastructure to support this, a novel approach was adopted to develop both the hardware and software.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

The device described in this article was used to conduct community outreach visits in the catchment area of a rural clinic in San José del Negrito, outside the city of San Pedro Sula in Honduras. Outreach visits consist of health screenings and a physical examination conducted at eight schools surrounding the clinic. These outreach visits occur over a 10-day period and are conducted every 6 months when a brigade of volunteer medical professionals and students visit the clinic from the United States. The development of the device was undertaken as a service-learning project by a team from the Global Health Informatics Institute located in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Device requirements and capabilities

The process of developing our system began with the identification of user and device requirements. Due to the location and environment in which outreach visits are conducted, the unit’s hardware had to be capable of operating without access to reliable AC power. The hardware had to be portable to allow easy transportation between schools. Furthermore, the hardware needed to withstand temperature extremes and protect against water damage during transportation.

To track pediatric growth, the device had to identify children during repeated visits and record their weight and height. The 2006 WHO formulas for calculating Z-scores based on age, weight, and height were used to assess the nutrition status of each child. Age was calculated based on the child’s date of birth, which was recorded when creating the initial patient record. Z-scores for each child were compared to standard growth charts. Data were exported from the unit using a USB drive and aggregated to determine the prevalence of malnutrition and calculate average Z-scores.

Field testing plan

Field testing was conducted during two brigade visits, when the unit was used to conduct outreach health screening at local schools. The initial test was to determine whether the unit was functional and to compile a list of bugs and feature requests. Once the bugs had been resolved, a second test was conducted during the subsequent brigade visit. One person per brigade was trained on how to use the device to ensure that data input was consistent. Three schools were chosen as pilot sites, following which the unit’s use was expanded to cover all schools within the clinic’s catchment area. Routine outreach data, which were previously recorded on paper, were collected electronically by the unit, which required ongoing consent from guardians regarding care provision. The PFU was handled only by the person inputting data to avoid security concerns.

RESULTS

Device requirements and capabilities

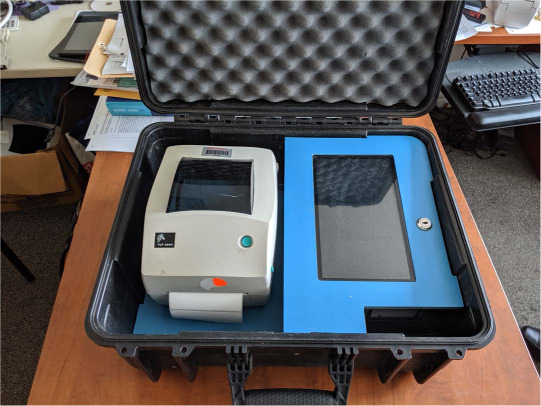

The primary requirement for this intervention was a robust, portable device that could be transported to schools over rough terrain and difficult weather conditions. To meet this requirement, we developed a portable field unit (PFU) with a 10-inch touch-screen display and a Raspberry Pi computer (Raspberry Pi Foundation, Cambridge, UK). A rechargeable 12-volt sealed lead-acid battery was incorporated in the design to allow continued use of the unit in remote off-grid settings. A barcode scanner and a thermal label printer completed the set of peripheral devices. All the equipment was housed in a commercially available waterproof carrying case commonly used for carrying cameras/fragile equipment. The PFU is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Portable field unit with thermal printer and touchscreen installed in case.

The unit assigned each student a unique number. Students were given a copy of their demographic record together with their unique student number, which was printed on an adhesive label using the thermal printer. To expedite the process of reviewing and recording data, the printed copy of the student demographic record also had the unique student number printed as a barcode. By scanning this barcode in the application, the student’s record could be retrieved and opened. In the absence of the identification card, a student record could be retrieved using a search function based on different criteria such as name, sex, date of birth and name of school.

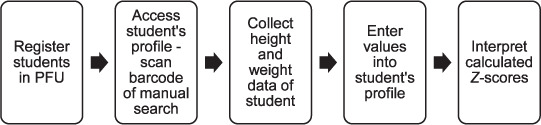

Figure 2 shows the proposed workflow for a field nutrition status assessment using the unit. The process begins with registering the student, if they have not already done so. This procedure involves the collection of information about the student’s name, gender, date of birth, and school. Once data are recorded, a label with demographic identifiers is printed and affixed to a plastic card to create an identification card for the student. The student’s record then opens and height (in cm) and weight (in kg) are recorded. From this data, Z-scores for weight-for-age, height-forage, and body mass index (BMI) for age are calculated and displayed in a table with any previously collected data.

FIGURE 2.

Data entry workflow. PFU = portable field unit.

Field testing and preliminary data

The unit was first field tested in Honduras in September 2019, and then in February 2020. During these brigades, outreach visits to the three pilot schools were conducted using the unit. Demographic information for 234 students (ages 4–16 years) was pre-populated into the PFU to shorten data entry time in the field. All children present during brigades were included. During the first brigade, 180 of the 234 registered students had measurements for age, height and weight recorded. Z-scores for these students were calculated and stored in the unit. During the second brigade, a total of 142 of the 234 registered students were assessed and their measurements recorded in the unit. Of these, 112 (62.2% of the original 180-student cohort) were assessed and had measurements recorded in the previous outreach visit. A total of 210 children were assessed and 322 measurements were recorded (Table). The data collected in these two brigades provided clinical decision support in real time by presenting physicians with a table of Z-scores over time. The analysis of these data revealed 24 cases of moderate-to-severe malnutrition (BMI-Z –2.0), with a combined average BMI-Z of –0.32 necessitating referrals. Referrals for counseling and intervention from the brigade were communicated to families by the teacher if no parent was present during the examination.

TABLE.

A summary of the data collected from the two brigades

| September 2019 Brigade (n = 180) mean ± SD | February 2020 Brigade (n = 142) mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI for age Z-score, | − 0.46 ± 1.11 | − 0.15 ± 1.14 |

| Height for age Z-score | − 1.16 ± 1.11 | − 1.13 ± 0.99 |

| Weight for age Z-score | − 0.76 ± 1.21 | − 0.77 ± 1.16 |

SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index.

The PFU was transported to schools without compromising the integrity of the device, and was used during the rainy season with no loss of function or water damage. The battery charge lasted long enough for the unit not to be shut down while in use. The label printer and barcode scanner both functioned as intended and were able to reliably print and scan when prompted by the user. The touchscreen functioned consistently with no appreciable calibration issues or input lag.

From a software usability perspective, the PFU operator was able to navigate the unit efficiently to identify a child during a second visit, either via the search function or by barcode scanning. Data entry into the unit worked reliably and calculated values were displayed clearly in a table for comparison. The insight garnered was then used to help physicians in determining when it was appropriate to intervene.

The total cost of all components to build the PFU was USD350. A second-hand thermal label printer costing USD75 was used to keep the total cost of the unit low.

DISCUSSION

We successfully achieved the primary outcome of this project, which was to develop a device capable of monitoring growth among students to facilitate early identification of malnutrition and stunting cases, and to assess the reliability of data entry and Z-score output. The PFU is in line with the research previously conducted in this field; it is unique in that it demonstrates a method to track pediatric growth electronically, portably, and offline. While tablets and smartphones can be used similarly, the PFU is also able to create an adhesive label to facilitate longitudinal tracking.

From September to February, there were slight variations in the averages of Z-scores for BMI, height, and weight-for-age. This variation could be due to a difference in the cohort of students that presented that day. Due to the lack of a centralised method of notifying students of our visit, we were forced to rely on word of mouth from local health committee members to inform students of our impending arrival. This likely contributed to the large differences in the number of students at a given school in one brigade vs. the subsequent one.

Data collected from the PFU were used to guide clinical decision-making by enabling real-time calculation of Z-scores. Of the 112 students with multiple data points entered into the unit, 24 children identified as either at-risk (down-trending Z-scores) or moderate to severely malnourished (Z-score values <−2), and were appropriately referred for further evaluation at the central clinic in San Jose. An improving Z-score value for a malnourished child could serve to demonstrate how an intervention between the first and second brigade positively impacted growth.

Given that our unit’s initial primary data output was the calculation of Z-scores, we chose not to integrate with other projects at this point. In the future, adding a notification for participation in nutrition programs, including chispuditos and the first 1,000 days of life program will be considered. Once further data points have been collected, average Z-scores at different schools can be compared to determine which communities require the most attention.

Other possible future goals of the project include adding a field to specify whether the child has been referred for further evaluation - either for medical reasons, impaired vision, or dental abnormality. Although the integration of past medical history, medications, allergies, and other conditions could all be useful additions, the cost and time needed to incorporate these into the unit were not feasible at this point. In the future, locally collected data could be compared against the national data collected by the UNICEF for the Global Nutrition Report.14 Possible consequences of this work include diverting funds and time away from other less useful projects; if the unit’s information does not result in an improvement in stunting, the community may be disenfranchised from future interventions.15

CONCLUSION

Having identified moderate to severe malnutrition as a national concern in Honduras, our focus was to create a device to quantify the extent of malnutrition in the pediatric population in the community. We developed and successfully piloted a PFU and software unit capable of operating in the absence of reliable electricity, accurately identifying children, and calculating Z-scores for clinical decision support. This initial assessment suggests that the PFU could be an effective means of identifying at-risk children; the data and insights gained from it would be essential in long-term planning and analysis of nutritional interventions in this setting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding for this work was supported by Shoulder to Shoulder Pittsburgh/San Jose.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Sinha KK. Malnutrition | The Problem of Malnutrition. In: Caballero B, editor. Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 3660–3667. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B012227055X007276 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elia M. Guidelines for detection and management of malnutrition. Red-ditch, UK: Maidenhead Malnutrition Advis Group MAG Standing Comm BAPEN; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Agriculture Organization Understanding the true cost of malnutrition. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2014. http://www.fao.org/zhc/detail-events/en/c/238389/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulland A. BMJ. 2016. Malnutrition and obesity coexist in many countries, report finds; p. 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(3):279–286. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bygbjerg IC. Double burden of noncommunicable and infectious diseases in developing countries. Science. 2012;337(6101):1499–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1223466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0–59 months in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-9):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan American Health Organization Health systems profile. Honduras: monitoring and analyzing health systems change/reform. Washington DC, USA: PAHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan American Health Organization Honduras. Washington DC, USA: PAHO; 2017. https://www.paho.org/salud-en-las-americas-2017/?p=4280 . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villanueva LM, Palacios AM. A novel distribution method to provide micro-nutrients at a community level improves linear growth in young Guatemalan children. FASEB J. 2017;31(S1):639.9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Mathile Institute Dayton, OH, USA: What we do. https://www.mathileinstitute.org/what-we-do . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iannotti L, Gillespie S. Successful community nutrition programming: lessons from Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Washington DC, USA: Academy for Educational Development, The LINKAGES Project; 2002. https://eric. ed.gov/?id=ED467467 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.iPediatric EHR A flawless platform to keep track of a child’s growth & nutrition. Cincinnati, OH, USA: iPatientCare; 2017. https://ipatientcare.com/blog/ipediatric-ehr-to-keep-track-of-a-childs-growth/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Nutrition Report Country Nutrition Profiles. 2022. https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/latin-america-and-caribbean/central-america/honduras/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nabarro D, Chinnock P. Growth monitoring—inappropriate promotion of an appropriate technology. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26(9):941–948. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]