Abstract

Targeting proteasome with proteasome inhibitors (PIs) is an approved treatment strategy in multiple myeloma that has also been explored pre-clinically and clinically in other hematological malignancies. The approved PIs target both the constitutive and the immunoproteasome, the latter being present predominantly in cells of lymphoid origin. Therapeutic targeting of the immunoproteasome in cells with sole immunoproteasome activity may be selectively cytotoxic in malignant cells, while sparing the non-lymphoid tissues from the on-target PIs toxicity. Using activity-based probes to assess the proteasome activity profile and correlating it with the cytotoxicity assays, we identified B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) to express predominantly immunoproteasome activity, which is associated with high sensitivity to approved proteasome inhibitors and, more importantly, to the immunoproteasome selective inhibitors LU005i and LU035i, targeting all immunoproteasome active subunits or only the immunoproteasome β5i, respectively. At the same time, LU102, a proteasome β2 inhibitor, sensitized B-CLL or immunoproteasome inhibitor-inherently resistant primary cells of acute myeloid leukemia, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia to low doses of LU035i. The immunoproteasome thus represents a novel therapeutic target, which warrants further testing with clinical stage immunoproteasome inhibitors in monotherapy or in combinations.

Keywords: immunoproteasome, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, plasma cell leukemia, proteasome inhibitors, LU005i, LU035i, activity-based probes, proteasome activity

1. Introduction

The differentiation of human B-cells from their progenitors to immunoglobulin-secreting cells is completed in a series of clearly recognized, discrete stages. At each step of the B-cell differentiation, a cell can undergo malignant transformation, thus giving rise to various malignancies arising from the B-cell lineage. Poorly differentiated acute B-cell malignancies, such as B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) are more common in children than in adults, while the most prevalent B-cell malignancies in adults are chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) or malignancies of terminally differentiated plasma cells, such as multiple myeloma (MM) or plasma-cell leukemia (PCL). While B-CLL is the most common chronic type of leukemia in adults, the most common type of acute leukemia in adults is acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a malignancy arising from a myeloid progenitor (National Cancer Institute: https://seer.cancer.gov accessed on 20 January 2022).

The treatment of these hematological malignancies has considerably improved in the past years with the recent approval of several novel agents for the treatment of AML, B-ALL, B-CLL and MM, which contributed to expanding the palette of therapeutic options in these diseases [1,2,3,4]. However, the main reason for treatment failure in a significant proportion of adult patients with leukemias or MM is the occurrence of intrinsic or acquired drug resistance in a subset of malignant cells that is responsible for the development of relapse or refractory disease with a dismal prognosis [5,6,7,8]. Subsequently, as the development of drug resistance is one of the limiting factors affecting long-term efficacy of anti-leukemic or anti-myeloma drugs, the search for therapies with novel mechanisms of action is an ongoing challenge.

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs), such as boronate-based bortezomib and ixazomib and epoxyketone-based carfilzomib specifically inhibit proteasomes, which are large protein complexes with three main catalytic subunits β1, β2 and β5, providing the proteasome with caspase-like, trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like activities to digest and recycle ubiquitin-tagged proteins [9]. By design, PIs bind to the active pocket of the proteasome β5 subunit, which was initially identified as a rate-limiting protease for functional proteasomal degradation. Only recently, the importance of other proteasome subunits has been shown. The proteasome β5 subunit allosterically activates the β1 subunit [9,10,11], but its co-inhibition has not shown a strong additional cytotoxic effect, whereas the functional β2 subunit co-inhibition together with β5 inhibition is cytotoxic in MM and breast cancer cells [12,13,14].

PIs are cornerstones of treatment of plasma cell malignancies, such as MM, PCL, and mantle cell lymphoma [15]. Moreover, they were extensively evaluated for the therapy of other myeloid or lymphoid malignancies. Although the pre-clinical data showed efficacy of PIs bortezomib and carfilzomib in B-CLL [16,17,18,19], AML [20,21] and ALL [22], clinical observations of PIs in monotherapy in B-CLL, AML or ALL [23,24,25,26] did not fully confirm this data as most of the patients experienced only modest anti-leukemic activity of PIs. Moreover, the patients experienced several toxic side effects from bortezomib therapy, whereas carfilzomib was rather well tolerated.

In the cells of hematopoietic origin, the constitutive proteasome is replaced by the immunoproteasome, in which the standard β1, β2 and β5 catalytic subunits are replaced by the inducible subunits β1i (LMP2), β2i (MECL-1) and β5i (LMP7) [27]. Immunoproteasome expression is noticeably induced upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [28]. The primary function of immunoproteasome is to generate more hydrophobic peptides, which are more likely to be presented by HLA molecules (MHC class I molecules) [29,30], but it also plays an important role in protein homeostasis control. Not only does it regulate quality control and clearance of oxidized proteins and protein aggregates generated under cytokine-induced oxidative stress, but it also controls protein transcription and levels of transcription factors that regulate multiple signaling pathways [31].

Given the abundance of immunoproteasome in several leukemia types or myeloma cells, selective targeting of the immunoproteasome is an attractive treatment option [32]. The recent development of immunoproteasome-specific PI may further allow selective targeting of such increased immunoproteasome activity to overcome drug resistance, while sparing the vast majority of tissues not expressing the immunoproteasome, thus considerably reducing the secondary effects and toxicities related to PI treatment.

To date, the proteasome/immunoproteasome composition and activity in the most common subtypes of adult leukemia is unknown. Moreover, we lack data that compare the activity of individual proteolytic subunits of the constitutive versus the immunoproteasome to the cytotoxic activity of the approved PI or novel immunoproteasome-selective PIs. Therefore, we used a cocktail of activity-based proteasome probes (ABPs), which covalently bind to the proteolytically-active sites of the constitutive and the immunoproteasome in a way that corresponds to their catalytic activity [33], to assess the proteasome content in primary samples of patients with AML, B-CLL, B-ALL, MM and PCL. Subsequently, we related the proteasome activity to the cytotoxicity of bortezomib and carfilzomib and of the novel immunoproteasome selective inhibitors LU005i and LU035i [34]. We identified B-CLL to have exclusively high immunoproteasome activity over the constitutive proteasome activity that may be used as a novel target for the immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors. Moreover, the malignancies inherently resistant to immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors may be sensitized to their cytotoxic activity by the selective inhibition of the proteasome β2 subunit.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients’ Samples

Primary samples of patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic B-cell lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), multiple myeloma (MM) and plasma cell leukemia (PCL) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy volunteers were obtained at the Clinics for Medical Oncology and Hematology, Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. All samples were obtained during routine diagnostic procedures after approval by the independent cantonal ethical committee and after obtaining written informed consent form in accordance with Helsinki Declaration guidelines.

B-ALL, AML, B-CLL and PCL samples were obtained from peripheral blood. B-ALL and AML samples were enriched by CD34+ selection (EasySep Human Cord Blood CD34 Positive Selection Kit II, StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). B-cell CLL samples were isolated using EasySep Direct Human B-CLL Cell Isolation Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). MM plasma cells samples were obtained from bone marrow aspirates, enriched by CD138+ selection using EasySep Human Whole Blood and Bone Marrow and CD138+ positive selection kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). PBMC were obtained by standard Ficoll gradient separation of the peripheral blood.

2.2. Cell Culture

Primary cells were thawed into RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin (all Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) and seeded for further analyses.

AMO-1 cell line was obtained from commercial sources (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC/LGC, Wesel, Germany). AMO-1 wild-type and AMO-1 PSMB5KO cell lines were maintained under standard conditions in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin. MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was used to rule out the mycoplasma contamination in the cell culture and the modified cell line was authenticated with its parental cell line by the STR-typing (at DSMZ, a German collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany).

2.3. CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout of PSMB5

Two different short guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting PSMB5 gene in positions spanning the proteolytically active site were designed by web-based tool CRISPOR [35], to generate a larger deletion in PSMB5 gene, as was described before [36]. The proteolytically active site of human β5c subunit was obtained from UniProt database (P28074). The sequences of the sgRNAs are as follows (with the PAM sequence in italics): PSMB5_g1: CCGCTACCGGTGAACCAGCGCGGG, PSMB5_g2: TGCCTCCCAGACGGTGAAGAAGG.

Briefly, sgRNAs PSMB5_g1 and PSMB5_g2 were cloned into lentiCRISPRv2 vector plasmid carrying both Cas9 and guide RNA (a gift from Zhang’s lab; Addgene plasmids #52961). Next, separate lentiviruses for PSMB5_g1 and PSMB5_g2 were produced by packaging plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2 (a gift from Trono’s lab; Addgene plasmids #12259 and #12260) and the lentiCRISPRv2 transfer plasmids in HEK-293-LentiX cells (Takara-Bio, Kusacu, Japan) following protocol described elsewhere [37]. AMO-1 cells were transduced with PSMB5_g1 and PSMB5_g2 viral particles in 1:1 ratio and cells with stably introduced CRISPR/Cas9 vectors were selected by puromycin (2 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland). Single-cell derived colonies of AMO-1 cells were obtained using MethoCult Classic (#H4434, StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). The clones were screened for larger deletions in PSMB5 using PCR with primers spanning the deletion site (PSMB5_del_F: AGGAAGTGAAGCTGTGACGG and PSMB5_del_R: CGTTCCCAGAAGCTGCAATC) that produces PCR product of 1442 bp in non-deleted PSMB5 and 250 bp in deleted PSMB5. Sanger sequencing was performed to confirm the presence of a deletion in the on-target sequence of genome. Moreover, the clones were screened for knock-out of the β5c activity by ABP and a single-cell derived colony with confirmed deletion and no β5c activity was chosen for further analyses.

2.4. Chemicals

Bortezomib and carfilzomib were obtained from commercial sources (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA). LU005i, LU035i, LU025c, LU102 and ABP were synthesized at Leiden University. Detailed information regarding proteasome inhibitors used in the study is presented in Table S1.

2.5. Proteasome β-Subunits Profiling with Activity-Based Proteasome Probes Labelling

Activity of proteasome subunits was assessed on a protein lysate by SDS-PAGE after 1 h/37 °C incubation with the set of subunit-selective activity-based probes (ABP) that differentially visualize individual activities of β1, β2 and β5 subunits of the constitutive and the immunoproteasome, as described [33]. Protein subunits were separated by SDS-PAGE, gel images were acquired using Fusion Solo S Western Blot and Chemi Imaging System (Vilber Lourmat, Collégien, France). The quantification of the activity was performed using Fiji (open source image processing package based on ImageJ) [38]. For each sample, the ratio of activity of the immunoproteasome vs. constitutive proteasome subunits was calculated by dividing the band intensity of each of the immunoproteasome subunits by the band intensity of the corresponding constitutive proteasome subunit.

2.6. CTG Viability Assay

An amount of 1 × 104 of cells were seeded per well into a white, flat bottom 96-well plate (Corning, Root, Switzerland). The cells were exposed to increasing doses of proteasome inhibitors in 100 µL of standard media per well for 48 h and cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Only samples where the untreated controls showed high ATP production were used in the analysis. The cytotoxicity of the drugs was normalized to control—untreated cells—and for each sample a dose-response curve to each tested chemical was generated.

2.7. Lactate Dehydrogenase Quantification

Levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, assessed in U/L) from peripheral blood of the patients were determined during patients’ routine diagnostic procedures at the Cantonal Hospital, St. Gallen.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Dose-response curves were generated using nonlinear fit. The IC50 of each chemical was determined using nonlinear regression analysis from dose-response curves. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for the comparison of statistically significant differences between the samples. Correlation coefficients between the activity ratios of β5i/c, the cytotoxicity of proteasome inhibitors and LDH levels were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation, and p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Statistical evaluation was performed in GraphPad Prism v8 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. B-CLL Shows Exclusive Predominant Activity of the Immunoproteasome

Initially, the activity of both types of proteasomes were tested in different hematological malignancies, including 16 AML, 3 B-ALL, 17 B-CLL, 6 MM and 5 PCL and in PBMC samples obtained from six healthy donors. Detailed characteristics of patients/samples included in the study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of patients included in the study.

| AML | B-ALL | B-CLL | MM | PCL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nr of patients | 16 | 3 | 17 | 6 | 5 |

| Male-females (%) | 62–38% | 33–67% | 65–35% | 50–50% | 20–80% |

| Age (median; min–max) | 64 (32–84) | 35 (28–38) | 69 (54–81) | 74 (56–84) | 60 (51–69) |

AML = acute myeloid leukemia, B-ALL = B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, MM = multiple myeloma, PCL = plasma-cell leukemia.

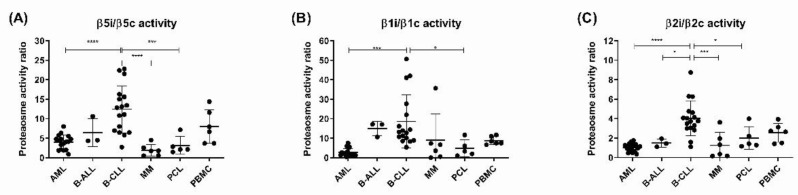

In each sample, activity of each of the proteolytically active β-subunits was determined by ABP and is expressed as a ratio between the respective immunoproteasome and the constitutive proteasome subunit (β5i/c, β1i/c and β2i/c). While most of the malignancies show activity of both types of the proteasomes, B-CLL samples show increased activity of the immunoproteasome active sites β5i, β1i and β2i over the corresponding β5c, β1c and β2c sites (Figure 1A–C). The most significant differences were observed in the activity ratios for β5 and β2 subunits, where B-CLL differed significantly in β5i/c activity ratio from AML, T-ALL, MM and PCL (Figure 1A) and in β2i/c activity ratio from AML, B-ALL, MM and PCL (Figure 1C). Deeper analysis of B-CLL cohort of patients (for basic biological and clinical information about the B-CLL cases, see Supplementary Table S2) showed that levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) correlate positively with the β5i/β5c activity ratio (Spearman r = 0.6818; p = 0.0251, Supplementary Figure S1A). Of note, PBMC samples show rather heterogeneous activity profile of the β5i/β5c, as they are a mixture of different cell types with different proteasome activities (as, for example, normal B-cells predominantly express β5i) [39]. Nevertheless, from the malignant entities of a B-cell origin, B-CLL shows a unique profile of high relative immunoproteasome activity, which is not seen in other acute or chronic B-cell malignancies and which correlates with levels of LDH, a general marker of tumor burden.

Figure 1.

Profile of the activity of the immunoproteasome subunits over constitutive proteasome subunits determined by ABP labelling in different hematological malignancies. (A) Comparison between the ratio of activity of proteasome β5i versus β5c, data represent mean ± SD. (B) Comparison between the ratio of activity of proteasome β1i versus β1c, data represent mean ± SD. (C) Comparison between the ratio of activity of proteasome β2i versus β2c, data represent mean ± SD. In all analyses, statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, where * represents p < 0.05, *** represents p < 0.001 and **** represents p < 0.0001. AML = acute myeloid leukemia, B-ALL = B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, MM = multiple myeloma, PCL = plasma-cell leukemia, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

3.2. B-CLL Is the Most Sensitive to Bortezomib and Carfilzomib

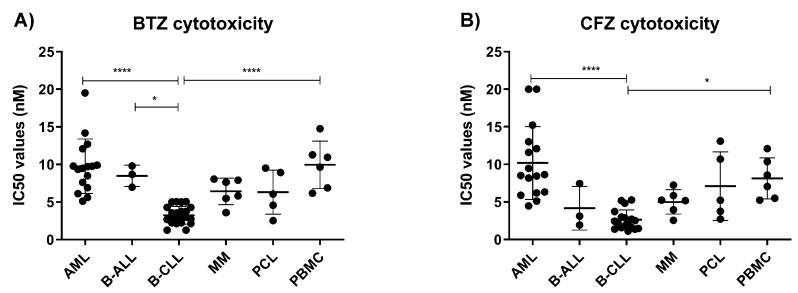

The approved PIs for MM therapy are designed to target the chymotrypsin-like site (β5 subunit) of the constitutive and immunoproteasome, which is the most important target to inhibit proteasomal proteolysis [40,41]. It was later discovered that higher doses of bortezomib co-inhibit caspase-like sites (the β1 subunits), while carfilzomib co-inhibits trypsin-like sites (the β2 subunits). Moreover, they target the active sites of the immunoproteasome at low nanomolar doses, comparable to doses necessary for the inhibition of the active sites of the constitutive proteasome [42,43,44]. Therefore, we tested the cytotoxicity of bortezomib and carfilzomib in our cohort of hematological malignancies by analyzing dose-response curves and obtaining IC50 value for each sample. B-CLL was the most sensitive cohort of samples to both bortezomib and carfilzomib, supporting our previous observations (Figure 2A,B). Specifically, B-CLL samples were significantly more sensitive to bortezomib and carfilzomib than AML, which was the most resistant cohort of samples in our analysis. Importantly, only B-CLL cells were also significantly more sensitive to bortezomib and carfilzomib than PBMCs, showing an opportunity for a selective toxicity of malignant cells and less systemic toxicity associated with the use of these PIs.

Figure 2.

Profile of the IC50 values of the approved proteasome inhibitors in different hematological malignancies. (A) Comparison of IC50 values of bortezomib determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies, data represent mean ± SD. (B) Comparison of IC50 values of carfilzomib determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies, data represent mean ± SD. In all analyses, statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, where * represents p < 0.05 and **** represents p < 0.0001. AML = acute myeloid leukemia, B-ALL = B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, MM = multiple myeloma, PCL = plasma-cell leukemia, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells, BTZ = bortezomib; CFZ = carfilzomib.

Nevertheless, although B-CLL is uniformly sensitive to bortezomib and carfilzomib, there was no correlation between sensitivity of the individual samples to bortezomib or carfilzomib and their β5i/c activity ratio. This suggests that B-CLL depend on functional proteasome activity, irrespective of its type.

3.3. Immunoproteasome-Selective Proteasome Inhibitors Are Selectively Cytotoxic in B-CLL and Their Cytotoxicity Correlates with Immunoproteasome Activity

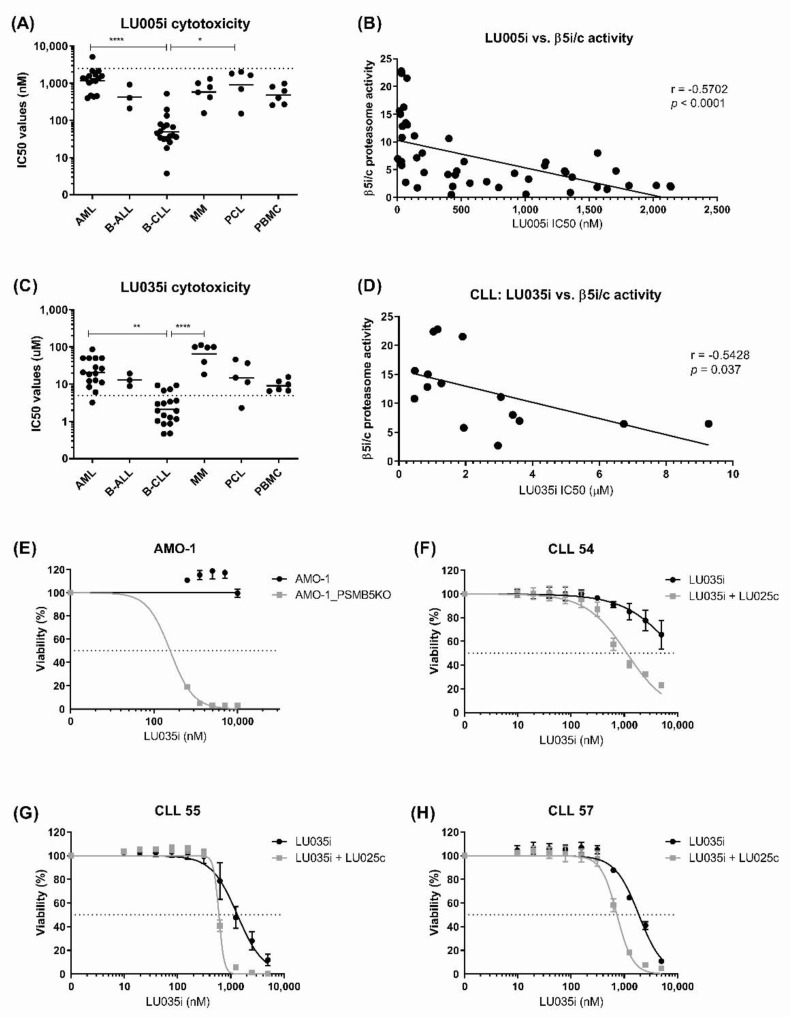

Since B-CLL shows the highest relative immunoproteasome activity, it could be exclusively sensitive to novel selective immunoproteasome inhibitors. These inhibitors could preserve efficacy on malignant cells, but significantly reduce treatment-emergent toxicities by sparing other tissues with little to no immunoproteasome activity [32]. First, we tested the cytotoxic activity of novel immunoproteasome inhibitors on a cohort of various hematological malignancies. We chose LU005i for selective inhibition of the immunoproteasome active subunits β5i, β1i and β2i with predominant activity on β5i > β1i > β2i at low micromolar doses [34] (Supplementary Figure S2). LU005i was cytotoxic in low micromolar range (below 2.5 µM, where it retains the selectivity for the immunoproteasome subunits) in all tested hematological malignancies. Moreover, it was significantly more cytotoxic in B-CLL cells with high relative immunoproteasome activity, in contrast to AML or PCL, which keep both types of active proteasomes (Figure 3A). Cytotoxicity of LU005i correlated with the activity ratios of the β5i/c subunit across the whole cohort of hematological malignancies tested (Figure 3B); however, we did not observe any significant correlation between the activity ratios of individual β subunits and cytotoxicity of LU005i in B-CLL.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity of the immunoproteasome-selective proteasome inhibitors in hematological malignancies. (A) Comparison of IC50 values of LU005i determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies. Data represent geometric mean ± geometric SD, statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, where * represents p < 0.05 and **** represents p < 0.0001. Line represents a 2.5 µM dose, to which the inhibitor retains its selectivity. (B) Correlation between the activities of constitutive vs. the immunoproteasome β5 subunits and the cytotoxicity of LU005i in 15 AML, 3 B-ALL, 17 CLL, 6 MM and 5 PCL samples. Correlation and statistical significance were obtained using Spearman’s rank correlation. (C) Comparison of IC50 values of LU035i determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies, data represent geometric mean ± geometric SD. In samples, where the IC50 value was not reached, it was arbitrarily given an IC50 = 100 µM. Statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, where ** represents p < 0.01 and **** represents p < 0.0001. Line represents a 5 µM dose, to which the inhibitor retains its selectivity. (D) Correlation between the activities of constitutive vs. the immunoproteasome β5 subunits and the cytotoxicity of LU035i in 17 CLL samples. Correlation and statistical significance were obtained using Spearman’s rank correlation. (E) Dose-response curves of AMO-1 and AMO-1 PSMB5 knock-out cells to LU035i determined 48 h after the treatment. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (F–H) Dose-response curves of three B-CLL samples to LU035i alone or in combination with 1 µM LU025c determined 48 h after the treatment. Data represent mean ± SD of tetraplicate. AML = acute myeloid leukemia, B-ALL = B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, MM = multiple myeloma, PCL = plasma-cell leukemia, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells; LU005i = proteasome β5i + β2i + β1i selective inhibitor; LU035i = proteasome β5i selective inhibitor; LU025c = proteasome β5c selective inhibitor; i = immunoproteasome, c = constitutive proteasome.

The chymotrypsin-like site of the immunoproteasome (β5i) is more hydrophobic and has different structure and size than the chymotrypsin-like site of the constitutive proteasome (β5c) [45]. Therefore, it allows the design of selective β5i inhibitors. Since β5i is rate-limiting for the proteolytic activity of the immunoproteasome, as is the β5c for the activity of the constitutive proteasome, we hypothesized that the sole inhibition of the β5i subunit activity with LU035i may be sufficient to induce cytotoxicity in cells with predominant immunoproteasome activity. LU035i is an epoxyketone-based selective PI that is selective for the inhibition of the β5i subunit up to 5 µM concentration [34] (Supplementary Figure S3). Almost all B-CLL samples were sensitive to cytotoxic activity of LU035i at low micromolar doses (Figure 3C), in contrast to the AML, B-ALL, MM and PCL samples, suggesting that β5i may be a novel therapeutic target in B-CLL. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of LU035i correlated with the β5i/c activity ratios in B-CLL (Figure 3D), whereas it could not be properly assessed in other malignancies, since the inhibitor did not reach the IC50 values here or else reached it at very high doses, where it most likely loses the β5i selectivity. At the same time, as we observed a positive correlation between β5i/β5c activity ratios and levels of LDH, we likewise observed here a negative correlation between LDH levels and IC50 values of LU035i (Supplementary Figure S1B, Spearman r = −0.6545, p = 0.0336).

Previously, we have shown that in cells with both β5i and β5c activities, inhibition of β5i is not cytotoxic, as the residual β5c activity can substitute for inhibited β5i activity [12]. Since we observed the correlation between β5i/c activity ratios and cytotoxicity of LU035i in B-CLL, we aimed to assess if the cytotoxicity of LU035i is solely related to predominant β5i activity or also to other factors. At the same time, we aimed to assess to what extent a presence of β5i only, or both β5i and β5c activities, affects the cytotoxicity of LU035i. Towards this aim, we first knocked-out the β5c activity in AMO-1 MM cell line by introducing a deletion in PSMB5, including the enzymatic active site. We subsequently obtained a single-cell derived colony with no detectable β5c activity, but with present β5i activity (Supplementary Figure S4). At the same time, we chemically inhibited the residual β5c activity with selective β5c inhibitor LU025c [46] in B-CLL samples, which showed lower cytotoxicity of LU035i. As expected, LU035i was not cytotoxic in AMO-1 wild-type cells up to 10 µM concentration, whereas it was cytotoxic in AMO-1_PSMB5KO cells at sub micromolar doses (Figure 3E). Likewise, inhibition of residual β5c with LU025c sensitized B-CLL cells to LU035i (Figure 3F–H). Of note, AMO-1_PSMB5KO cells completely lacking the active β5c were not sensitized to LU035i by LU025c up to 3 µM concentration, whereas AMO-1 wt were sensitized significantly (Supplementary Figure S5A,B), confirming that the residual β5c activity is the only factor affecting cytotoxicity of LU035i in malignant cells. Therefore, high relative activity of the β5i subunit is a signature of B-CLL representing a novel therapeutic target for immunoproteasome β5-selective inhibitor LU035i, associated with low cytotoxicity on cells with low relative immunoproteasome activity.

3.4. β2-Selective Proteasome Inhibitor Sensitizes Hematological Malignancies to β5i-Selective Immunoproteasome Inhibitor

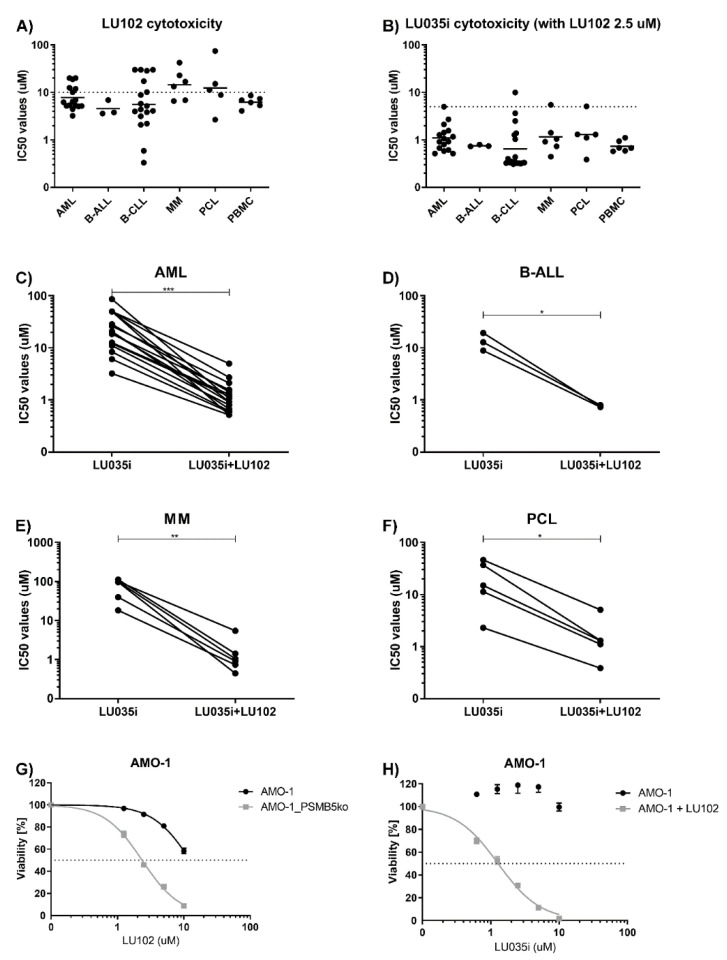

Co-inhibition of the proteasome β2c and β2i activity sensitizes MM cells to immunoproteasome inhibitor ONX-0914 [47]. Thus, we assessed if samples inherently not sensitive to β5i inhibition may be sensitized to LU035i by co-inhibition of the β2c and β2i activity with selective inhibitor LU102 [48]. In living cells, LU102 sub-totally inhibits both β2c and β2i activity at 10 µM dose and retains its β2 selectivity up to 20 µM [12]. We have not observed any difference in the cytotoxicity of LU102 across different malignancies (Figure 4A). However, 2.5 µM LU102, a dose not affecting the viability in most of the samples, significantly sensitized all tested hematological malignancies to low doses of LU035i, where it retains selectivity only for the β5i inhibition (Figure 4B–F). Moreover, LU102 alone was more cytotoxic in AMO-1_PSMB5KO cells, as compared to AMO-1 wild-type cells (Figure 4G), suggesting that lower drug doses are needed to induce cytotoxicity in the absence of β5c activity. This aligns with previous data, where in the presence of β5i and β5c inhibition, lower doses of LU102 were needed to achieve complete β2i and β2c inhibition [12]. At the same time, 2.5 µM dose of LU102, not affecting the viability of AMO-1 wild-type cells, significantly sensitized the cells to β5i-selective immunoproteasome inhibitor LU035i (Figure 4H). Therefore, combination of the immunoproteasome selective inhibitors with β2c and β2i selective inhibitor allows using lower doses of both drugs to induce cytotoxicity in hematological malignancies, such as AML, MM and PCL.

Figure 4.

β2-selective inhibitor sensitizes hematological malignancies to immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors. (A) Comparison of IC50 values of LU102 determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies, data represent geometric mean ± geometric SD. Statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (B) Comparison of IC50 values of LU035i combined with fixed dose of LU102 (2.5 µM) determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in various hematological malignancies. Data represent geometric mean ± geometric SD. Statistical significance was obtained with ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (C) Paired comparison of IC50 values of LU035i combined with fixed dose of LU102 (2.5 µM) determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in AML samples. Statistical significance was obtained with paired t-test, where *** represents p < 0.001. (D) Paired comparison of IC50 values of LU035i combined with fixed dose of LU102 (2.5 µM) determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in B-ALL samples. Statistical significance was obtained with paired t-test, where * represents p < 0.05. (E) Paired comparison of IC50 values of LU035i combined with fixed dose of LU102 (2.5 µM) determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in MM samples. Statistical significance was obtained with paired t-test, where ** represents p < 0.01. (F) Paired comparison of IC50 values of LU035i combined with fixed dose of LU102 (2.5 µM) determined 48 h after the continuous treatment in MM samples. Statistical significance was obtained with paired t-test, where * represents p < 0.05. (G) Dose-response curves of AMO-1 wt and AMO-1 PSMB5 knock-out cells to LU102 determined 48 h after the treatment. Data represent mean ± SD. (H) Dose-response curves of AMO-1 cells to LU035i alone or in combinations with 2.5 µM LU102, determined 48 h after the treatment. Data represent mean ± SD. AML = acute myeloid leukemia, B-ALL = B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B-CLL = B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, MM = multiple myeloma, PCL = plasma-cell leukemia, PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cells; LU035i = proteasome β5i selective inhibitor; LU102 = proteasome β2c and β2i selective inhibitor; i = immunoproteasome, c = constitutive proteasome.

4. Discussion

Targeting immunoproteasome is a treatment strategy clinically tested in autoimmune diseases and experimentally explored in pediatric ALL or adult malignancies, such as MM [47,49,50,51]. Here we show that B-CLL cells possess increased activity of the immunoproteasome subunits over the constitutive proteasome active subunits, which is associated with their high sensitivity to approved PIs bortezomib and carfilzomib or novel immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors LU005i and LU035i. While bortezomib and carfilzomib inhibit both the constitutive and the immunoproteasome, they have been shown unlikely to move forward in B-CLL as a single agent given the minimal efficacy observed. At the same time, high selectivity and cytotoxic activity of LU035i in B-CLL, and significant correlation between the cytotoxicity and the immunoproteasome β5i activity assessed by ABP labelling suggests that proteasome inhibition is still interesting to pursue as part of combination strategies in which efficacy of another drug may be improved by inhibition of proteasome-mediated protein breakdown. Moreover, proteasome activity assessment should be used for patients’ stratification and identification of patients that may benefit the most from such therapy.

The molecular mechanism underlying high immunoproteasome activity in B-CLL remains to be elucidated. The activity of the immunoproteasome can be reversibly stimulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ or TNF-α, or by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [52,53,54,55], which may potentially influence the composition of proteasome in B-CLL; however, multiple other factors may be involved. At the same time, as we observed a positive correlation between high relative β5i/β5c activity and levels of LDH, it suggests that higher relative immunoproteasome activity is associated with more severe disease and poorer prognosis [56]. Increased LDH levels are associated with poor prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes, AML and B-CLL [57,58,59]. It remains to be elucidated whether immunoproteasome inhibition decreases LDH levels, a potential useful marker of disease control.

Currently, two immunoproteasome inhibitors have entered clinical evaluation for the treatment of autoimmune disorders. Both, ONX-0914 and KZR-616, are selective irreversible inhibitors of β5i (LMP7) and β1i (LMP2) sites of the immunoproteasome [60,61]. Following the discovery of their activity against autoimmune disorders, their anti-tumor activities were tested in selected groups of patients with leukemia. ONX-0914 showed activity in pediatric ALL, in contrast to rather low activity in pediatric AML [49]. More recently, ONX-0914 has been shown to be effective in pediatric T-ALL cases with t (4; 11) (q21; q23) chromosomal translocation that leads to the expression of MLL–AF4 fusion protein conferring poor outcome [50]. Newly, orally bioavailable reversible immunoproteasome β5i inhibitor M3258 showed efficacy in diverse in vitro and in vivo MM models, a favorable safety profile and a lack of cardiac, respiratory, and neurobehavioral effects, supporting the initiation of a phase I clinical trial of M3258 in patients with relapsed/refractory MM (NCT04075721) [62,63]. In this study, we tested LU005i and LU035i irreversible immunoproteasome inhibitors, which selectively target immunoproteasome subunits over a broad concentration range up to micromolar doses [34]. Our data extend previous observations and shows that a sole inhibition of the β5i subunit in B-CLL is sufficient to induce cytotoxicity, which proportionally corresponds to the high relative immunoproteasome β5i activity ratio. At the same time, healthy PBMCs are less vulnerable to LU035i-induced cytotoxicity, thereby offering a therapeutic window at which cells expressing both types of proteasomes are spared from on-target toxicity of LU035i.

Previous data suggested that β2 inhibition ex vivo sensitizes adult malignancies, such as MM, or pediatric B-ALL and T-ALL cases to ONX-0914 or LU035i [47,49,50]. Our data support these results and show that β2 inhibition provided by LU102 sensitizes B-CLL cells to β5i inhibition provided by LU035i. More importantly, malignancies with the activity of both types of proteasomes, such as AML, B-ALL, MM or PCL, which are intrinsically resistant to LU035i, can be sensitized to its cytotoxicity by LU102. These findings offer novel therapeutic possibility for the treatment of malignancies with lack of effective therapies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing composition and activity of proteasome/immunoproteasome in the most common adult hematological malignancies and demonstrating the exclusive activity of the immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors in B-CLL. We acknowledge the limitation of our study, which is the low number samples used in the analysis that does not allow further stratification of patients to major cytogenetically defined subgroups with different prognoses. We observed consistently low activity ratios between the constitutive vs. the immunoproteasome β-subunits in AML, MM and PCL, whereas in B-CLL, the activity ratios varied considerably from high to intermediate/low. These observations require further studies on larger cohorts of patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we provide a strong rationale for further in vivo studies of immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors in B-CLL, which may provide higher activity and lower off-target toxicity in combination setting with other drugs used for B-CLL therapy. At the same time, combination of immunoproteasome-selective and β2-selective inhibitors may be effective in hematological malignancies with poor prognosis and lack of effective therapies, such as AML or PCL.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cells11050838/s1, Figure S1: Correlation of LDH with proteasome activity and cytotoxicity of the immunoproteasome selective inhibitor in B-CLL primary samples. Figure S2: Inhibitory profile of pan-immunoproteasome selective inhibitor LU005i. Figure S3: Inhibitory profile of β5-immunoproteasome selective inhibitor LU035i. Figure S4: Profile of active proteasome β-subunits in AMO-1 wild-type cells and in AMO-1 cells with PSMB5 knock-out. Figure S5: Dose-response curves of AMO-1wild-type and AMO-1_PSMB5 knock-out cells to β5i inhibition in a presence or absence of the β5c inhibition. Table S1: Detailed characteristics of proteasome inhibitors used in the study. Table S2: Basic biological and clinical characteristics of B-CLL cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., M.M.-L., C.D. and L.B.; methodology, A.B., M.K., E.M., H.S.O. and C.D.; software, A.B.; validation, L.B.; formal analysis, L.B.; investigation, A.B., M.K. and L.B.; resources, A.B., E.M., H.S.O., C.D. and L.B.; data curation, L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., M.K., M.M.-L., E.M. and C.D.; visualization, L.B.; supervision, C.D.; project administration, L.B.; funding acquisition, A.B., L.B. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen Research Committee internal grant No. 21/20.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Canton St. Gallen and by Ethics Committee of Eastern Switzerland (EKSG09/057 and EKOS09/057).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

There were no data deposited in publicly available data-repositories within this pro-ject. However, any data generated within this project are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Daver N., Wei A.H., Pollyea D.A., Fathi A.T., Vyas P., DiNardo C.D. New directions for emerging therapies in acute myeloid leukemia: The next chapter. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:107. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-00376-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furstenau M., Eichhorst B. Novel Agents in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: New Combination Therapies and Strategies to Overcome Resistance. Cancers. 2021;13:1336. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chim C.S., Kumar S.K., Orlowski R.Z., Cook G., Richardson P.G., Gertz M.A., Giralt S., Mateos M.V., Leleu X., Anderson K.C. Management of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: Novel agents, antibodies, immunotherapies and beyond. Leukemia. 2018;32:252–262. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavralidis A., Brunner A.M. Novel Therapies in the Treatment of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2020;15:294–304. doi: 10.1007/s11899-020-00591-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurnari C., Pagliuca S., Visconte V. Deciphering the Therapeutic Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:8505. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeAngelo D.J., Jabbour E., Advani A. Recent Advances in Managing Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2020;40:330–342. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_280175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skanland S.S., Mato A.R. Overcoming resistance to targeted therapies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2021;5:334–343. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis L.N., Sherbenou D.W. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies to Overcome Drug Resistance in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers. 2021;13:1686. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groll M., Heinemeyer W., Jager S., Ullrich T., Bochtler M., Wolf D.H., Huber R. The catalytic sites of 20S proteasomes and their role in subunit maturation: A mutational and crystallographic study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10976–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinemeyer W., Fischer M., Krimmer T., Stachon U., Wolf D.H. The active sites of the eukaryotic 20 S proteasome and their involvement in subunit precursor processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25200–25209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisselev A.F., Akopian T.N., Castillo V., Goldberg A.L. Proteasome active sites allosterically regulate each other, suggesting a cyclical bite-chew mechanism for protein breakdown. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:395–402. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80341-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besse A., Besse L., Kraus M., Mendez-Lopez M., Bader J., Xin B.T., de Bruin G., Maurits E., Overkleeft H.S., Driessen C. Proteasome Inhibition in Multiple Myeloma: Head-to-Head Comparison of Currently Available Proteasome Inhibitors. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018;26:340–351.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraus M., Bader J., Geurink P.P., Weyburne E.S., Mirabella A.C., Silzle T., Shabaneh T.B., van der Linden W.A., de Bruin G., Haile S.R., et al. The novel beta2-selective proteasome inhibitor LU-102 synergizes with bortezomib and carfilzomib to overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance of myeloma cells. Haematologica. 2015;100:1350–1360. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.109421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weyburne E.S., Wilkins O.M., Sha Z., Williams D.A., Pletnev A.A., de Bruin G., Overkleeft H.S., Goldberg A.L., Cole M.D., Kisselev A.F. Inhibition of the Proteasome beta2 Site Sensitizes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to beta5 Inhibitors and Suppresses Nrf1 Activation. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017;24:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuazon S.A., Holmberg L.A., Nadeem O., Richardson P.G. A clinical perspective on plasma cell leukemia; current status and future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:23. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pahler J.C., Ruiz S., Niemer I., Calvert L.R., Andreeff M., Keating M., Faderl S., McConkey D.J. Effects of the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, on apoptosis in isolated lymphocytes obtained from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:4570–4577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamothe B., Wierda W.G., Keating M.J., Gandhi V. Carfilzomib Triggers Cell Death in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia by Inducing Proapoptotic and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Responses. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:4712–4726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almond J.B., Snowden R.T., Hunter A., Dinsdale D., Cain K., Cohen G.M. Proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis of B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells involves cytochrome c release and caspase activation, accompanied by formation of an approximately 700 kDa Apaf-1 containing apoptosome complex. Leukemia. 2001;15:1388–1397. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S.V., Hertlein E., Lu Y., Sass E.J., Lapalombella R., Chen T.L., Davis M.E., Woyach J.A., Lehman A., Jarjoura D., et al. The proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib functions independently of p53 to induce cytotoxicity and an atypical NF-kappaB response in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:2406–2419. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang J., Rhyasen G., Bolanos L., Rasch C., Varney M., Wunderlich M., Goyama S., Jansen G., Cloos J., Rigolino C., et al. Cytotoxic effects of bortezomib in myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia depend on autophagy-mediated lysosomal degradation of TRAF6 and repression of PSMA1. Blood. 2012;120:858–867. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-407999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stapnes C., Doskeland A.P., Hatfield K., Ersvaer E., Ryningen A., Lorens J.B., Gjertsen B.T., Bruserud O. The proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and PR-171 have antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on primary human acute myeloid leukaemia cells. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;136:814–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K., Inukai T., Imamura T., Yano M., Tomoyasu C., Lucas D.M., Nemoto A., Sato H., Huang M., Abe M., et al. Anti-leukemic activity of bortezomib and carfilzomib on B-cell precursor ALL cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faderl S., Rai K., Gribben J., Byrd J.C., Flinn I.W., O’Brien S., Sheng S., Esseltine D.L., Keating M.J. Phase II study of single-agent bortezomib for the treatment of patients with fludarabine-refractory B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;107:916–924. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Awan F.T., Flynn J.M., Jones J.A., Andritsos L.A., Maddocks K.J., Sass E.J., Lucas M.S., Chase W., Waymer S., Ling Y., et al. Phase I dose escalation trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2015;56:2834–2840. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1014368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wartman L.D., Fiala M.A., Fletcher T., Hawkins E.R., Cashen A., DiPersio J.F., Jacoby M.A., Stockerl-Goldstein K.E., Pusic I., Uy G.L., et al. A phase I study of carfilzomib for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2016;57:728–730. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1076930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarlo C., Buccisano F., Maurillo L., Cefalo M., Di Caprio L., Cicconi L., Ditto C., Ottaviani L., Di Veroli A., Del Principe M.I., et al. Phase II Study of Bortezomib as a Single Agent in Patients with Previously Untreated or Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia Ineligible for Intensive Therapy. Leuk. Res. Treatment. 2013;2013:705714. doi: 10.1155/2013/705714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murata S., Takahama Y., Kasahara M., Tanaka K. The immunoproteasome and thymoproteasome: Functions, evolution and human disease. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:923–931. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niewerth D., Kaspers G.J., Assaraf Y.G., van Meerloo J., Kirk C.J., Anderl J., Blank J.L., van de Ven P.M., Zweegman S., Jansen G., et al. Interferon-gamma-induced upregulation of immunoproteasome subunit assembly overcomes bortezomib resistance in human hematological cell lines. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2014;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verbrugge S.E., Scheper R.J., Lems W.F., de Gruijl T.D., Jansen G. Proteasome inhibitors as experimental therapeutics of autoimmune diseases. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2015;17:17. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0529-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raule M., Cerruti F., Benaroudj N., Migotti R., Kikuchi J., Bachi A., Navon A., Dittmar G., Cascio P. PA28alphabeta reduces size and increases hydrophilicity of 20S immunoproteasome peptide products. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tubio-Santamaria N., Ebstein F., Heidel F.H., Kruger E. Immunoproteasome Function in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Cells. 2021;10:1577. doi: 10.3390/cells10071577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhn D.J., Orlowski R.Z. The immunoproteasome as a target in hematologic malignancies. Semin. Hematol. 2012;49:258–262. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bruin G., Xin B.T., Kraus M., van der Stelt M., van der Marel G.A., Kisselev A.F., Driessen C., Florea B.I., Overkleeft H.S. A Set of Activity-Based Probes to Visualize Human (Immuno)proteasome Activities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:4199–4203. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bruin G., Huber E.M., Xin B.T., van Rooden E.J., Al-Ayed K., Kim K.B., Kisselev A.F., Driessen C., van der Stelt M., van der Marel G.A., et al. Structure-based design of beta1i or beta5i specific inhibitors of human immunoproteasomes. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:6197–6209. doi: 10.1021/jm500716s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haeussler M., Schonig K., Eckert H., Eschstruth A., Mianne J., Renaud J.B., Schneider-Maunoury S., Shkumatava A., Teboul L., Kent J., et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 2016;17:148. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer D.E., Canver M.C., Orkin S.H. Generation of genomic deletions in mammalian cell lines via CRISPR/Cas9. J. Vis. Exp. 2015;95:e52118. doi: 10.3791/52118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber K., Thomaschewski M., Benten D., Fehse B. RGB marking with lentiviral vectors for multicolor clonal cell tracking. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt C., Berger T., Groettrup M., Basler M. Immunoproteasome Inhibition Impairs T and B Cell Activation by Restraining ERK Signaling and Proteostasis. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2386. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kisselev A.F., Goldberg A.L. Proteasome inhibitors: From research tools to drug candidates. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisselev A.F., van der Linden W.A., Overkleeft H.S. Proteasome inhibitors: An expanding army attacking a unique target. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blackburn C., Gigstad K.M., Hales P., Garcia K., Jones M., Bruzzese F.J., Barrett C., Liu J.X., Soucy T.A., Sappal D.S., et al. Characterization of a new series of non-covalent proteasome inhibitors with exquisite potency and selectivity for the 20S beta5-subunit. Biochem. J. 2010;430:461–476. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demo S.D., Kirk C.J., Aujay M.A., Buchholz T.J., Dajee M., Ho M.N., Jiang J., Laidig G.J., Lewis E.R., Parlati F., et al. Antitumor activity of PR-171, a novel irreversible inhibitor of the proteasome. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6383–6391. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Screen M., Britton M., Downey S.L., Verdoes M., Voges M.J., Blom A.E., Geurink P.P., Risseeuw M.D., Florea B.I., van der Linden W.A., et al. Nature of pharmacophore influences active site specificity of proteasome inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:40125–40134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huber E.M., Basler M., Schwab R., Heinemeyer W., Kirk C.J., Groettrup M., Groll M. Immuno- and constitutive proteasome crystal structures reveal differences in substrate and inhibitor specificity. Cell. 2012;148:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin B.T., de Bruin G., Huber E.M., Besse A., Florea B.I., Filippov D.V., van der Marel G.A., Kisselev A.F., van der Stelt M., Driessen C., et al. Structure-Based Design of beta5c Selective Inhibitors of Human Constitutive Proteasomes. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:7177–7187. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Downey-Kopyscinski S., Daily E.W., Gautier M., Bhatt A., Florea B.I., Mitsiades C.S., Richardson P.G., Driessen C., Overkleeft H.S., Kisselev A.F. An inhibitor of proteasome beta2 sites sensitizes myeloma cells to immunoproteasome inhibitors. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2443–2451. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018016360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geurink P.P., van der Linden W.A., Mirabella A.C., Gallastegui N., de Bruin G., Blom A.E., Voges M.J., Mock E.D., Florea B.I., van der Marel G.A., et al. Incorporation of non-natural amino acids improves cell permeability and potency of specific inhibitors of proteasome trypsin-like sites. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:1262–1275. doi: 10.1021/jm3016987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niewerth D., Franke N.E., Jansen G., Assaraf Y.G., van Meerloo J., Kirk C.J., Degenhardt J., Anderl J., Schimmer A.D., Zweegman S., et al. Higher ratio immune versus constitutive proteasome level as novel indicator of sensitivity of pediatric acute leukemia cells to proteasome inhibitors. Haematologica. 2013;98:1896–1904. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.092411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins T.W., Downey-Kopyscinski S.L., Fields J.L., Rahme G.J., Colley W.C., Israel M.A., Maksimenko A.V., Fiering S.N., Kisselev A.F. Activity of immunoproteasome inhibitor ONX-0914 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia expressing MLL-AF4 fusion protein. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:10883. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90451-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Besse L., Besse A., Kraus M., Maurits E., Overkleeft H.S., Bornhauser B., Bourquin J.P., Driessen C. High Immunoproteasome Activity and sXBP1 in Pediatric Precursor B-ALL Predicts Sensitivity towards Proteasome Inhibitors. Cells. 2021;10:2853. doi: 10.3390/cells10112853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heink S., Ludwig D., Kloetzel P.M., Kruger E. IFN-gamma-induced immune adaptation of the proteasome system is an accelerated and transient response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9241–9246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501711102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groettrup M., Standera S., Stohwasser R., Kloetzel P.M. The subunits MECL-1 and LMP2 are mutually required for incorporation into the 20S proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8970–8975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Javitt A., Barnea E., Kramer M.P., Wolf-Levy H., Levin Y., Admon A., Merbl Y. Pro-inflammatory Cytokines Alter the Immunopeptidome Landscape by Modulation of HLA-B Expression. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:141. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pickering A.M., Koop A.L., Teoh C.Y., Ermak G., Grune T., Davies K.J. The immunoproteasome, the 20S proteasome and the PA28alphabeta proteasome regulator are oxidative-stress-adaptive proteolytic complexes. Biochem. J. 2010;432:585–594. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wulaningsih W., Holmberg L., Garmo H., Malmstrom H., Lambe M., Hammar N., Walldius G., Jungner I., Ng T., Van Hemelrijck M. Serum lactate dehydrogenase and survival following cancer diagnosis. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;113:1389–1396. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wimazal F., Sperr W.R., Kundi M., Vales A., Fonatsch C., Thalhammer-Scherrer R., Schwarzinger I., Valent P. Prognostic significance of serial determinations of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the follow-up of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19:970–976. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Germing U., Hildebrandt B., Pfeilstocker M., Nosslinger T., Valent P., Fonatsch C., Lubbert M., Haase D., Steidl C., Krieger O., et al. Refinement of the international prognostic scoring system (IPSS) by including LDH as an additional prognostic variable to improve risk assessment in patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Leukemia. 2005;19:2223–2231. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu H., Xiong W., Li H., Lv R., Liu W., Yi S., Li Z., Qiu L. Prognostic Significance of Serum LDH in B Cell Chronic Lymphoproliferative Disorders: A Single-Institution Study of 829 Cases in China. Blood. 2016;128:5336. doi: 10.1182/blood.V128.22.5336.5336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Basler M., Lindstrom M.M., LaStant J.J., Bradshaw J.M., Owens T.D., Schmidt C., Maurits E., Tsu C., Overkleeft H.S., Kirk C.J., et al. Co-inhibition of immunoproteasome subunits LMP2 and LMP7 is required to block autoimmunity. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:e46512. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang C., Zhu H., Shao J., He R., Xi J., Zhuang R., Zhang J. Immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors: The future of autoimmune diseases? Future Med. Chem. 2020;12:269–272. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2019-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanderson M.P., Friese-Hamim M., Walter-Bausch G., Busch M., Gaus S., Musil D., Rohdich F., Zanelli U., Downey-Kopyscinski S.L., Mitsiades C.S., et al. M3258 Is a Selective Inhibitor of the Immunoproteasome Subunit LMP7 (beta5i) Delivering Efficacy in Multiple Myeloma Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021;20:1378–1387. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sloot W., Glaser N., Hansen A., Hellmann J., Jaeckel S., Johannes S., Knippel A., Lai V., Onidi M. Improved nonclinical safety profile of a novel, highly selective inhibitor of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 (M3258) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021;429:115695. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

There were no data deposited in publicly available data-repositories within this pro-ject. However, any data generated within this project are available upon request.