Abstract

Coronary artery disease is a complex cardiovascular disease involving an interplay of genetic and environmental influences over a lifetime. Although considerable progress has been made in understanding lifestyle risk factors, genetic factors identified from genome-wide association studies may capture additional hidden risk undetected by traditional clinical tests. These genetic discoveries have highlighted many candidate genes and pathways dysregulated in the vessel wall, including those involving smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and injury responses. Here, we summarize experimental evidence for a few genome-wide significant loci supporting their roles in smooth muscle cell biology and disease. We also discuss molecular quantitative trait locus mapping as a powerful discovery and fine-mapping approach applied to smooth muscle cell and coronary artery disease-relevant tissues. We emphasize the critical need for alternative genetic strategies, including cis/trans-regulatory network analysis, genome editing, and perturbations, as well as single-cell sequencing in smooth muscle cell tissues and model organisms, under both normal and disease states. By integrating multiple experimental and analytical modalities, these multidimensional datasets should improve the interpretation of coronary artery disease genome-wide association studies and molecular quantitative trait locus signals and inform candidate targets for therapeutic intervention or risk prediction.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, gene editing, genome-wide association study, quantitative trait loci, risk factors, vascular smooth muscle cells

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide.1 Despite advances in medical treatments and prevention strategies, there has been an increased prevalence in developing countries.2,3 CAD is caused by a chronic accumulation of cholesterol deposits and inflammation in the blood vessel wall and often manifests in myocardial infarction (MI).4 It is now well established that an array of interacting genetic and environmental risk factors contribute equally to disease susceptibility.5,6 Since the discovery of the first genetic association with CAD located at chromosome 9p21, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 160 individual loci for CAD/MI.7–9 Many of these loci harbor genes that are organized into discrete signaling pathways, such as lipoprotein metabolism, NO/cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate), TGFB (transforming growth factor β), PDGF (platelet derived growth factor), extracellular matrix, inflammation, etc8,10,11 Although it remains to be determined whether these genes are causally associated with CAD, many are already supported by in vitro or in vivo experimental evidence.12–19 There still remain a significant number of disease loci containing genes with little or no relevant functional annotations, suggesting these loci may highlight novel disease processes.

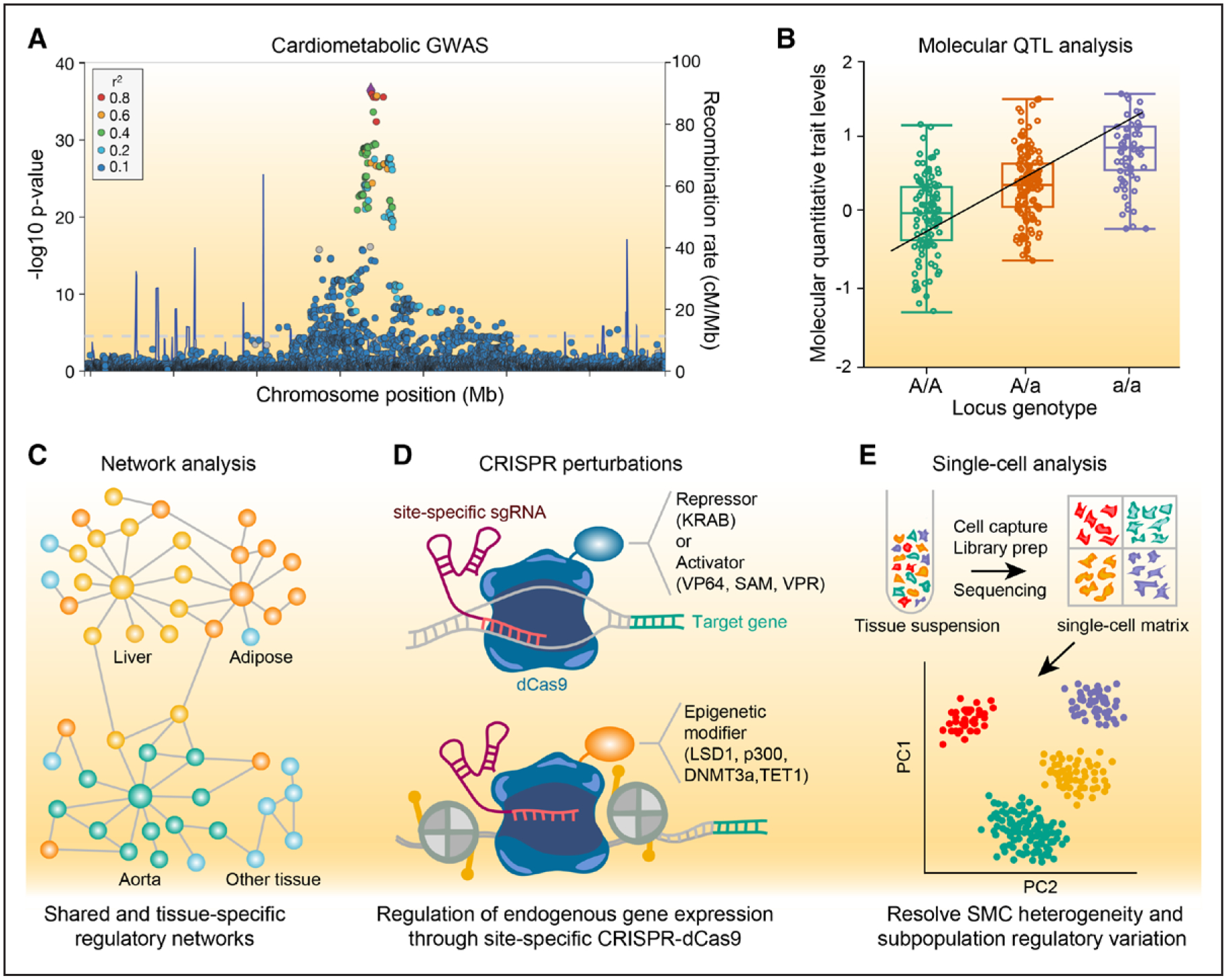

Multiple cell types have been linked to CAD pathogenesis, including smooth muscle cells (SMCs), endothelial cells, and macrophages. Thus, it seems likely that CAD-associated loci also operate through cell type–dependent regulatory pathways. Given that the majority of associated loci involve noncoding genetic variants predicted to affect gene expression, large-scale genomic consortia, such as Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx),20 Encyclopedia of DNA Elements,21 and Roadmap Epigenomics,22 have been critical to map these regulatory profiles across different human tissues. Still, significant gaps exist for which there are no regulatory profiles for specific cell types related to coronary atherosclerosis. We and others have developed cell-specific genomic resources to enable fine-mapping of CAD GWAS loci in the appropriate context.23–25 Whereas many of these datasets involve bulk sequencing, more recent efforts have established single-cell approaches to identify novel cell types that may contribute to the disease.26 Also, it is now appreciated that specific environmental contexts should be accounted for when developing these cell type–specific genomic datasets.27 In this brief review, we discuss the contribution of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) towards CAD risk, as informed by recent genetic discoveries (Figure 1 and Figure 2A). We highlight a few loci (eg, 9p21, TCF21, SMAD3, LMOD1) with predicted functional roles in SMC. We also discuss methods to discover SMC mediated genetic mechanisms through quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping (Figure 2B). Finally, we briefly discuss alternative approaches to prioritize SMC contributions to disease including CRISPR perturbations, network biology, and single-cell omics (Figure 2C through 2E). Together these methods may refine the role of SMC and intermediate cell types in relevant vessel wall signaling pathways and phenotypic transitions during CAD.

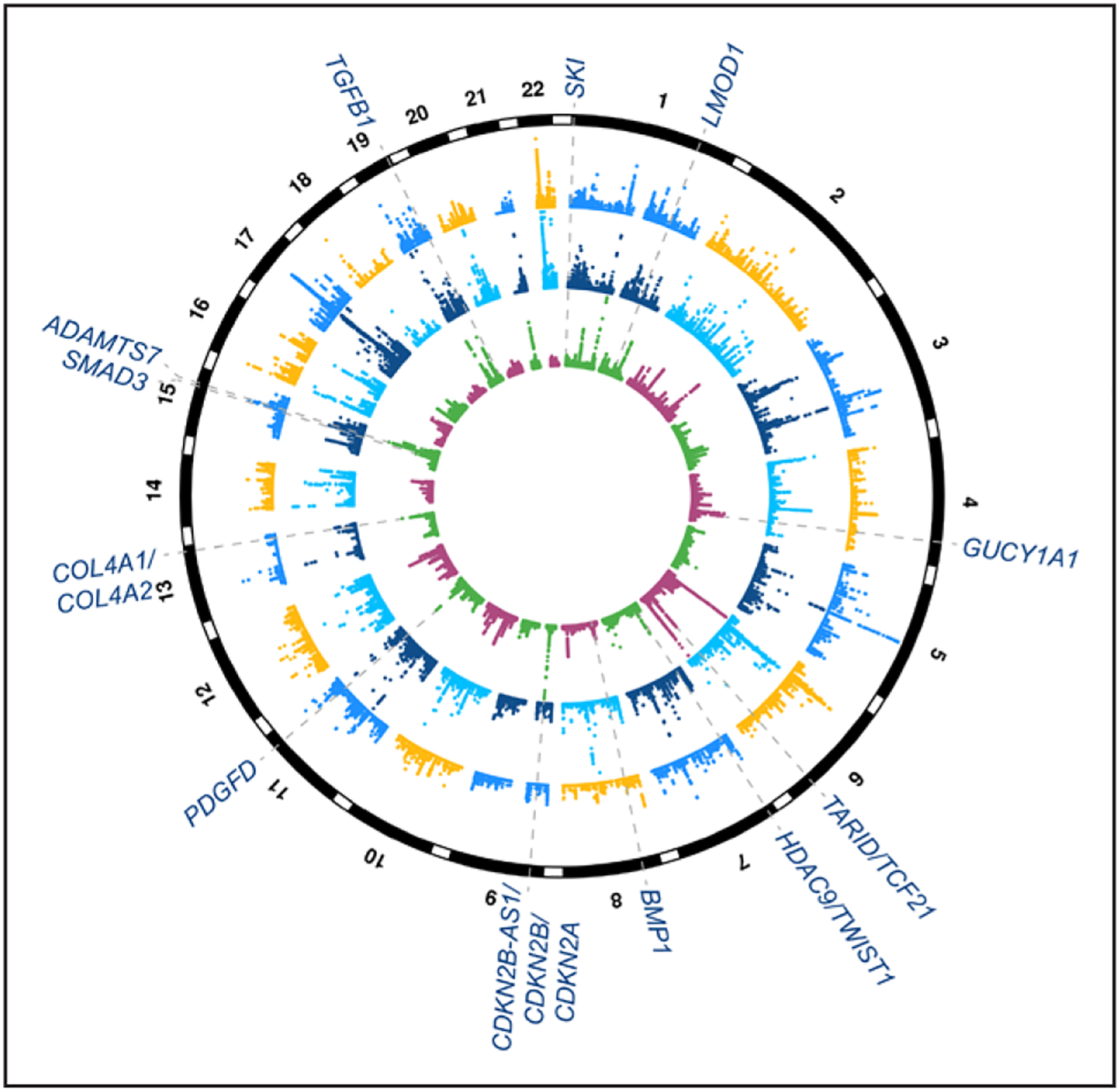

Figure 1.

Summary of coronary artery disease (CAD) genome-wide association study (GWAS) and expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) targeting genes with evidence of smooth muscle functions. Circular Manhattan plot depicting genome-wide significant loci associated with CAD from meta-analyses of CARDIoGRAMplusC4D (Coronary Artery Disease Genome Wide and Replication and Meta-Analysis Plus The Coronary Artery Disease Genetics Consortium) and UK Biobank data.7 Inner circle shows −log10 P values for CAD GWAS loci (maximum set to 50), and dashed lines and text highlight candidate causal genes with evidence of smooth muscle cell functions.28–38 Middle circle shows −log10 P values for eQTLs (maximum set to 100) identified from tibial artery in Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx; largest sample size for artery samples in this database) and outer circle shows −log10 P values for liver eQTLs (maximum set to 30) in GTEx. Note: these candidate target genes are based on existing experimental studies in the literature and may be subject to change with additional statistical and/or functional fine-mapping efforts.

Figure 2.

Overview of genetic approaches to investigate smooth muscle disease mechanisms. A, Example locus association plot showing a genome-wide association study (GWAS) signal for a cardiometabolic trait. Circles indicate individual single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated at a given P value and location across the genome. SNPs are color-coded for degree of linkage disequilibrium (r2) in a European population. Blue lines indicate recombination rate. B, Example molecular quantitative trait locus (molQTL) box plot showing the levels of a given molecular trait (eg, gene expression) that are correlated with genotype at a specific GWAS locus. Black line indicates linear regression for molecular trait-genotype association. C, Schematic of shared and tissue-specific gene regulatory networks derived from molQTLs related to cardiometabolic traits (eg, STARNET [Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task]). Yellow, orange, and green colored nodes indicate liver, adipose, and aorta-enriched regulatory signals, respectively, while blue colored nodes indicate shared or nontissue enriched signals. D, Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) approaches to perturb candidate gene expression levels using site-specific single guide RNA (sgRNA) and nuclease dead Cas9 (dCas9) fusion proteins to either repress/silence, activate, or epigenetically modify a particular regulatory region. E, Schematic of single-cell analysis (eg, single-cell RNA sequencing), showing single-cell gene matrix generated from bulk population of cells after single-cell capture, reverse transcription, library preparation and next-generation sequencing. Different colors represent uniquely labeled cell type based on cell-specific gene expression levels. Clustering shown for principal components (PC) 1 and 2 which can be used to resolve smooth muscle cell (SMC) heterogeneity and various subpopulations potentially altered by regulatory genetic variation. DNMT3a indicates DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha; KRAB, Kruppel-associated box; LSD1, lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A; p300, histone acetyltransferase p300; QTL, quantitative trait locus; SAM, synergistic activation mediator; TET1, ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1; VP64, viral protein 64; and VPR, viral protein R.

CAD GWAS Loci Harboring SMC Candidate Genes

9p21.3 (CDKN2B-AS1/CDKN2A/CDKN2B)

The first genetic locus associated with CAD risk was identified at chromosome 9p21.3 in 2007 by 3 independent groups.39–41 Despite the highly reproducible nature of this locus association with CAD, MI, and other conditions,42,43 the causal genes, variants, and underlying mechanisms in this region are still elusive. Adding to the intrigue, this locus is unlikely to be driven by traditional CAD risk factors, suggesting it encodes for hidden risk factors yet to be exploited for disease intervention. This locus contains many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in high linkage disequilibrium located within the long noncoding RNA, ANRIL (antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus or CDKN2B-AS1), and multiple nearby genes encoding the tumor suppressors CDKN2A (cyclic-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A), CDKN2B (cyclic-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B), and MTAP (methylthioadenosine phosphorylase).44 Several of the disease-associated SNPs located in the 3’ region of ANRIL correlate with ANRIL expression but also nearby genes, CDKN2A, and CDKN2B.44 Like many long noncoding RNA transcripts, ANRIL is capable of forming both linear and circular RNA.45 Holdt et al demonstrated that linear ANRIL confers proatherogenic cell functions through Alu element–mediated transregulatory networks.46,47 However, circular ANRIL inhibits atherogenic processes in SMC and macrophages by inducing nucleolar stress, p53 activation, and impairing ribosome biogenesis.48 The lead risk allele at 9p21 was correlated with reduced CDKN2B expression and increased cell cycle regulation in whole blood.44,46 Consistent with this mechanism, the CAD risk allele was associated with reduced CDKN2A and CDKN2B expression in vascular SMCs, and downregulated CDKN2B correlated with increased SMC proliferation and SMC content in atherosclerotic plaques.12 Loss of CDKN2B in mice has been linked to p53 mediated SMC apoptosis and aortic aneurysms,49 increased atherosclerosis through impaired efferocytosis,13 as well as hypoxic neovessel formation through dysregulated TGFB signaling.50 More recently, TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nuclease)-based genome editing of 9p21 risk haplotypes (including ANRIL) in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)–derived SMCs revealed altered transcriptional networks associated with CAD genes and SMC functions.51 Taken together, these studies highlight the complex and diverse roles of ANRIL and CDKN2B/CDKN2A in regulating SMC proliferation and related phenotypes during atherosclerosis.

6q23.2 (TCF21/TARID)

TCF21 (also known as Pod1/Epicardin/Capsulin) was first identified as a candidate causal gene for CAD-associated at chromosome 6q23.2 (P<1.1E-12).52 TCF21 (transcription factor 21) is a basic helix-loop-helix TF (transcription factor) involved in the development of the coronary vasculature.53,54 Two lead SNPs, rs12190287 and rs12524865, identified in Europeans and East Asians, respectively, were shown to regulate PDGFRB (platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta) mediated TCF21 expression in human coronary artery SMC (HCASMC) through 2 different AP-1 (activator protein 1) binding sites.14 Interestingly, the protective allele of the 3’UTR (3’ untranslated region) SNP, rs12190287, also perturbs a miR-224 (microRNA-224) seed binding site thereby stabilizing the TCF21 mRNA transcript.15 These 2 mechanisms are predicted to work in concert to fine-tune TCF21 levels. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq of TCF21 protein demonstrated genome-wide binding sites in genes related to cell migration and proliferation, which overlapped those of the promitogenic AP-1 TF family.16 Interestingly, TCF21 target genes are highly enriched for CAD GWAS variants in high linkage disequilibrium with SNPs in TCF21 binding sites, suggesting that TCF21 acts as a master regulator of other CAD-associated genes.16 RNA-seq of TCF21 knockdown in HCASMC revealed consistent target genes and implicated TCF21 in the suppression of SMC contractile markers and promotion of proliferation and migration.17 Lineage tracing of TCF21 in mouse arterial lesions and human atherosclerotic samples revealed staining localized to the subcapsular space during late-stage disease suggesting a role in stabilizing the fibrous cap.17 Recent CAD GWAS from the UK Biobank identified the lead SNP rs2327429 residing 0.5 kb 5′ of TCF21, also located within the first exon of antisense long noncoding RNA, known as TARID (TCF21 antisense RNA inducing promoter demethylation). This variant was identified as an expression QTL (eQTL) for both TCF21 and TARID in artery tissues in GTEx,20 STARNET (Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task),55 and our HCASMC dataset,23 suggesting coordinated regulation associated with CAD.56 Given the molecular interaction of TARID with the TCF21 promoter, this could potentially be exploited to deliver TARID (eg, via extracellular nanovesicles) to elevate TCF21 and promote plaque stability. Thus, future studies to directly modulate TARID in SMCs and CAD-related disease models are warranted.

15q22.33 (SMAD3)

As a pleiotropic signaling pathway involved in both coronary artery development and disease responses, the TGFB superfamily typically represses SMC migration, proliferation, and promotes extracellular matrix production.57,58 Both the canonical TGFB ligand and downstream mediators of this pathway are highly enriched among CAD GWAS loci.59–61 One of these mediators, SMAD3 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3) is hypothesized to be the causal gene at the CAD locus 15q22.33 based on epigenomic profiling and eQTL mapping in relevant tissues.18,24 The risk allele of candidate causal variant rs17293632 forms an AP-1 TF binding site, while the protective allele disrupts this site, resulting in reduced SMAD3 expression under PDGF-BB and TGFB stimulation in SMC.18,24 Loss of SMAD3 protein in HCASMC increased proliferation and reduced expression of SMC contractile markers.62 As a positive modulator of SMC differentiation, SMAD3 and TCF21 regulate opposing downstream transcriptional pathways.62 ChIP-seq analyses of both factors demonstrated similar target genes with limited overlap in their binding sites, suggesting a model in which the TCF21 mediated recruitment of HDACs (histone deacetylases) prevent the binding of Smad3.62,63 Consistent with the antimitogenic role of SMAD3 in vitro, in vivo experiments utilizing a femoral artery injury model showed loss of Smad3 increased proliferation and reduced collagen synthesis following vascular injury.64

1q32.1 (LMOD1)

LMOD1 (leimodin 1) was one of the recent vascular wall loci associated with CAD (P=7.77E-10).65 As a member of tropomodulin similar leiomodin family, LMOD1 functions as an actin filament nucleator that is highly enriched in smooth muscle containing visceral organs and arteries.66,67 Loss of Lmod1 in mice recapitulated a rare congenital disorder known as human megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome, characterized by defective intestinal and bladder function.67 Lmod1 global knockout reduces filamentous actin content and impairs contraction in visceral SMCs.67 Expression of LMOD1 is regulated by the SRF (serum response factor)/myocardin complex with 2 canonical CArG box located in its promoter region.66 Epigenomic, transcriptomic, and genetic fine-mapping studies pinpointed LMOD1 as the causal gene and identified a mechanism for a candidate causal CAD variant at this locus.19,24 The risk variant downregulates LMOD1 expression in atherosclerotic carotid artery tissue, as well as normal tibial arteries by perturbing a FOXO3 (forkhead box O3) binding site.19 Knockdown of LMOD1 in HCASMC increased proliferation and migration while inhibiting contraction.19 Complementary ex vivo immunohistochemistry staining of carotid atherosclerotic lesions reveal LMOD1 coexpression with SMC contractile markers, ACTA2 (smooth muscle alpha-2 actin), MYH11 (myosin heavy chain 11), CNN1 (calponin 1), and MYOCD (myocardin) and potently downregulated in response to atherogenic stimuli, shear stress, and carotid artery injury.68 In vivo data utilizing lineage traced mice localized LMOD1 expression to the fibrous cap with limited staining in the synthetic SMCs within the lesion.19 Taken together, these studies support a role of LMOD1 in maintaining the contractile SMC phenotype.

Quantitative Trait Mapping to Prioritize SMC Mechanisms

Expression and Splicing QTL in Atherosclerotic Tissues and SMC

Although CAD GWAS have revealed tremendous insights into vessel wall biology, it has been challenging to define causal genes and mechanisms at many of these putative vascular loci. One powerful strategy to refine these candidate genes and mechanisms involves molecular quantitative trait locus mapping, such as eQTL (Figure 2B). By correlating genetic variation with gene expression as an intermediate phenotype, it is possible to prioritize biologically plausible target genes from these associations.69–71 The GTEx project has provided large-scale mapping of eQTLs across 53 human tissues in an effort to define tissue-specific and broad insights into gene regulation.20,72 However, the majority of the samples profiled in GTEx have been heterogeneous, bulk tissues from nondiseased individuals making it difficult to delineate cell-type specific CAD regulatory mechanisms. The STARNET study is another large-scale study,55,73 which completed RNA-seq (RNA-sequencing) based eQTL analysis of 7 cardiometabolic tissues (atherosclerotic-lesion-free internal mammary artery, atherosclerotic aortic root, blood, subcutaneous fat, visceral abdominal fat, skeletal muscle, and liver) from ≈600 individuals undergoing coronary artery bypass graft procedures (Table). This dataset identified 2047 cardiometabolic GWAS SNPs with corresponding cis-eQTLs (≈61%; cis-eQTLs alter gene expression of nearby genes, while trans-eQTLs affect expression of distant genes, often located on different chromosomes). This is several fold more than the original GTEx dataset, emphasizing that not all disease regulatory variants can be detected in healthy tissues. Importantly this dataset was used to provide functional evidence for top candidate CAD regulatory variants identified from epigenomic profiling in HCASMC and coronary artery tissues.24 Other groups have integrated these datasets with GWAS for multiple common diseases using summary-based Mendelian randomization to reveal general insights into gene-trait associations.80 Additional disease-relevant cis-eQTL datasets have been generated from various cohorts, including STAGE (Stockholm Atherosclerosis Gene Expression),75 ASAP (Advanced Study of Aortic Pathology),77 and BiKE (Biobank of Karolinska Carotid Endarterectomies).76 These cohorts include both nonatherosclerotic and atherosclerotic bulk artery tissues, whereas the ASAP cohort includes additional datasets for medial and adventitial layers of the ascending aorta. Other omics data are available for these cohorts (eg, plasma proteomics); however, it is worth noting that their clinical utility could be limited to European populations (Table).

Table.

Human Artery Tissue and Cellular eQTL Data Resources Available

| Study | Tissue(s) | Sample size | Datasets | Platforms | Age (mean±SD) | Sex | Ancestry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athero-Express Biobank Study74 | Atherosclerotic carotid artery plaque | 1439 | Histological plaque characteristics, SNP genotyping, DNA methylation, proteomics (plasma, urine, plaque) | Sirius Red, α-actin, CD34, CD68, and H&E staining, Affymetrix and Illumina SNP arrays (genotyping), Illumina 450K Methylation array, mass spectrometry and Luminex (proteomics) | 68.8±9.3 | 67.9% male | 100% European |

| STARNET55 | Atherosclerotic aortic root, nonatherosclerotic internal mammary artery, blood, subcutaneous adipose, abdominal adipose, liver, skeletal muscle | ≈600 | SNP genotyping, gene expression, cis/trans-eQTLs, networks | Human OmniExpressExome 8v1 array (genotyping), RNA-seq (~15–30M reads/sample) | 65.8±8.7 | 70.3% male | 100% European |

| STAGE75 | Atheroscelrotic aortic root, nonatherosclerotic arterial wall internal mammary artery, liver, skeletal muscle, pericardial mediastinal visceral fat, carotid artery lesions | 109 | Gene expression, cis-eQTLs | Affymetrix, GenomeWideSNP_6 array (genotyping), Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (gene expression) | 66±8 | 90% male | 100% European |

| BiKE76 | Atherosclerotic carotid artery plaque from endoarterectomy and nonatherosclerotic control artery, plasma | 127 (plaque); 15 (control) | SNP genotyping, Gene expression, proteomics (plaque and plasma), cis-eQTLs, histology | Illumina Human 610 W- Quad Beadarrays (genotyping), Genotyping array, Affymetrix HT HU133A Plus array (gene expression), LC-MS/MS (proteomics) | 70.0±8.9 | 80.2% male | 100% European |

| ASAP77 | liver, mammary artery (medial and adventitial), and dilated and nondilated ascending aorta (medial and adventitial) | 117 | SNP genotyping, gene expression, plasma proteomics, cis-eQTLs | Illumina Human 610 W- Quad Beadarrays (genotyping), Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST array (gene expression), LC-MS/MS (proteomics) | 63.2±11.5 | ≈70.2% male | 100% European |

| HAEC78,79 | HAECs from ascending aortic segment of transplant donors (control and Ox-PAPC treatment) | 149 | SNP genotyping, gene expression, coexpression network analysis, chromatin accessibility | Affymetrix Human SNP Array 6.0 (genotyping), Affymetrix HT HU133A array (gene expression), ATAC-seq | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HCASMC23,24 | HCASMC from nondiseased donors | 52 | SNP genotyping, gene expression, cis-eQTL, sQTL, chromatin accessibility | Whole genome sequencing (30X), RNA-seq (≈50M reads/sample), ATAC-seq (≈45M reads/sample) | 39.0±15.4 | 65.3% male | 78% European, 10% Hispanic, 10% African, 2% Asian |

ASAP indicates Advanced Study of Aortic Pathology; ATAC-Seq, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin-sequencing; BiKE, Biobank of Karolinska Carotid Endarterectomies; eQTL, expression quantitative trait locus; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cell; HCASMC, Human coronary artery smooth muscle cells; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry; N/A, not applicable; Ox-PAPC, oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; sQTL, splicing quantitative trait locus; STAGE, Stockholm Atherosclerosis Gene Expression; and STARNET, Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task.

Recently, we completed eQTL mapping of HCASMC by profiling RNA-seq and whole genomes in 52 unrelated, multiethnic donors23 (Table). Despite the relatively small sample size, we leveraged allele-specific expression to discover 1220 significant loci, which were enriched in regions of open chromatin in HCASMC.23 Additionally, we identified 582 splicing QTLs, which may explain additional regulatory effects of genetic variants.81 Colocalization of eQTL and CAD GWAS signals using 2 methods revealed 5 significant loci, including FES, SMAD3, TCF21, PDGFRA, and SIPA1. In this study, we also quantitated the contribution of HCASMC to CAD risk and provided evidence that these cells capture a large portion of CAD heritability.23 Overall, these findings highlighted CAD risk genes related to vascular remodeling and phenotypic modulation in HCASMC. These data suggest that genetic upregulation of SMC genes (eg, SMAD3, PDGFRA, and SIPA1) may increase CAD risk, whereas upregulation of other SMC genes (eg, TCF21 and FES) may be atheroprotective. Although eQTL data from other coronary artery cell types (eg, endothelial cells, macrophages) are not available, human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) eQTLs from 147 transplant donors were previously used to identify 7 candidate causal CAD genes, including PPAP2B, GALNT4, MAPKAPK5, TCTN1, SRR, SNF8, and ICAM1.78 Similarly, a collection of eQTL datasets from the GRASP (Genome-Wide Repository of Associations Between SNPs and Phenotypes),82 STAGE study,83 Massachusetts General Hospital liver/adipose study,84 Cardiogenics consortium monocytes/macrophages study,85 and HAEC78 were used to identify 66 candidate CAD genes from 159 lead CAD SNPs.86

Additional gene regulatory mechanisms may be captured by profiling cells treated with disease-relevant environmental perturbations. While such studies have yet to be conducted in SMCs, gene x environment eQTLs have been identified in a cohort of 96 transplant donor HAEC treated with the proatherogenic oxidized phospholipid species, oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine.25,78,87 This dataset identified significant gene x environment eQTLs for about a third of the top 59 regulated transcripts, most of which were distal or trans-acting, but some of the strongest effects observed were cis-acting (eg, FGD6), suggesting that certain QTLs may be driven through specific response elements.87 Similar perturbation studies in a study of primary monocytes from 432 donors stimulated with interferon-γ or lipopolysaccharide identified response QTLs in more than half of all cis-eQTLs and revealed multiple master regulatory trans-eQTLs, such as the major histocompatibility complex and resolved putative causal genes at GWAS loci related to innate immune responses (eg, CARD9, ATM, and IRF8).88 Another study of 134 monocytes exposed to lipopolysaccharide or microbe-associated molecules identified 417 response QTLs across the different conditions.89 Both of these monocyte studies demonstrated stronger enrichment of immune-related GWAS signals in response QTLs compared with constant eQTLs. Together, these studies emphasize that regulatory effects of genetic variants associated with complex diseases are likely modified by specific contextual stimuli related to disease pathogenesis.

Chromatin Accessibility and TF Binding QTL in SMC

Given that the majority of genetic variation discovered through GWAS reside in noncoding regions, they are predicted to regulate gene expression through specific regulatory elements. Thus chromatin accessibility QTLs (caQTLs) may provide an additional layer of regulation to interpret these signals and could more directly explain cis-acting mechanisms. To date, there have not been any large caQTL studies in SMC; however, there have been a number of such studies in lymphoblastoid cell lines.81,90–92 Importantly, these studies demonstrated that 56% of candidate causal GWAS regulatory SNPs reside within the region of open chromatin itself.90 This is consistent with findings that 60% of all regulatory variants in these cells alter chromatin level phenotypes.81 Although initial studies mapped chromatin accessible sites using DNase I hypersensitivity sequencing,93–95 more recent efforts have leveraged the Tn5 transposase based assay for transposase accessible chromatin (ATAC)-seq,96 which requires a fraction of the starting material (≈50 000 cells) and time (≈3 h) to prepare libraries for sequencing, compared with previous approaches. We recently used ATAC-seq in growth factor (TGFB, PDGF-BB, PDGF-DD) stimulated HCASMC and frozen human coronary artery segments to map candidate regulatory variants and mechanisms for CAD loci.24 With the reduced search space (≈200–300 bp open chromatin region) and single-nucleotide resolution of this assay, we were able to prioritize 64 CAD-associated regulatory variants and provided experimental follow-up and candidate TF binding mechanisms (eg, TCF21 and AP-1) for 7 variants in these loci (SMAD3, 9p21.3, PDGFD, CCDC97/TGFB1, LMOD1, IL6R, and BMP1).24

Similar ATAC-seq studies have been conducted in 56 HAEC donors to elucidate the function of an intronic variant, rs17114036, in the PLPP3 CAD and ischemic stroke locus, encoding phospholipid phosphatase 3 (also known as PPAP2B [phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2B]).79,97 This study used the combined haplotype test,98,99 to perform caQTL mapping by comparing heterozygous and homozygous individuals at rs17114036. ATAC-seq signals spanning this region were strongly correlated with PLPP3 expression in HAEC, supporting a potential role as an enhancer of PLPP3. These authors provide additional evidence using luciferase reporter, ChIP, and CRISPR/Cas9 editing assays and demonstrate regulatory effects on PLPP3 through mechanosensing KLF2 (Kruppel-like factor 2) in response to unidirectional flow.79 caQTL mapping represents a powerful epigenomic approach to fine-map regulatory variants associated with CAD and other complex traits. However, additional assays, such as ChIP-seq, may be necessary to pinpoint true functional variants that alter TF binding.100

Other Molecular QTL Discoveries in SMC

To efficiently capture long-range interactions between enhancers and promoters, improved chromosome conformation capture (3C) or HiChIP (high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation) based assays such as HiChIP101 and Promoter Capture HiC101,102) have been developed. HiChIP was recently used in HCASMC using H3K27ac histone modification as bait to reveal genome-wide insights into the connectome in these cells.103 This study identified a number of enhancer-promoter interactions that may be influenced by CAD-associated genetic variants (eg, 9p21). Promoter capture HiC was recently used to identify interactions at 31 253 promoters in 17 different primary blood cell types.102 With the higher resolution of this approach, the distal impact of regulatory elements can be investigated in primary SMC to elucidate the effects of noncoding CAD regulatory variants. Other molecular QTLs have been discovered in blood plasma that have been associated with CAD. For instance, a large study of 6861 Framingham Heart Study participants identified 16 000 plasma protein QTLs of which a subset was tested for causal links to CAD.104 Another study identified 52 916 cis-methylation QTL and 2025 transmethylation QTL in whole blood with significant enrichment for CAD.105 More relevant to CAD pathology, the large Athero-Express Genomics study (N=1439), which has methylation, SNP genotyping, and histopathology data (Table), identified a number of variants associated with atherosclerotic plaque phenotypes, including the ALOX5AP locus associated with intraplaque vessel density and SMC content.106 More recent findings from this cohort identified 21 variants nominally associated with 7 histopathologic characteristics, demonstrating the impact of risk variants in a heterogeneous disease environment.74 Finally, as described above for eQTL associations, molecular QTL discoveries may be expanded by investigating the impact of genetic variants in more tightly controlled environments. A study in 17 human umbilical vein endothelial cell donors identified eQTLs, caQTLs, and candidate response elements associated with specific perturbations in these cells.27 Interestingly, some exposures were shown to amplify the underlying genetic effects, whereas others were buffered, pointing to the complex nature of these interactions on molecular phenotypes.

Other Approaches to Prioritize SMC Contributions to CAD

Network Analysis

Several studies have leveraged network analysis and unbiased systems genetics to uncover vascular wall genes with key biological roles in the development of CAD.59,61,75,107 As described above, cis- and trans-QTL discovery in the STARNET cohort were used to construct tissue-specific and shared regulatory networks for cardiometabolic traits55 (Figure 2C). Interestingly, trans-eQTL interactions between tissues involving CAD-associated SMC genes, such as TCF21, provided validation for epigenomic based molecular interactions in HCASMC.24,55 Recently, Lempiäinen et al108 used a network-based approach that first used a combination of genetic association, chromatin interactions, eQTL data, and mouse phenotypic data to prioritize causal genes at CAD loci. These CAD candidate genes were integrated with regulatory gene networks from the STAGE study and protein-protein interaction data to determine if these genes play regulatory roles in gene-protein modules (ie, subnetworks). Many of these modules are of functional relevance to SMC biology, including extracellular matrix organization and disassembly. These CAD candidate genes and modules were also scored for druggability. Notably, many of the top modules contained genes coding for druggable protein kinases and G-protein coupled receptors.108

CRISPR/Cas9 Perturbations

The development of genome editing technologies, such as CRISPR, now facilitates direct perturbations of CAD-associated risk variants or risk haplotypes. Although CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to disrupt genes with roles in dyslipidemia,109 there is a lack of CRISPR studies in SMCs in the context of CAD. Direct genome editing and clonal selection are difficult for human primary coronary artery SMCs because these cells often become senescent in culture and are pheno-typically heterogeneous across individuals and disease states. An alternative is to use human iPSCs to disrupt a CAD region of interest using genome editing and subsequently differentiate successfully edited cells into SMCs. As described above, TALEN editing of the complex 9p21.3 CAD locus in human iPSCs differentiated to SMCs highlighted precisely how this region alters SMC gene expression and function.51 Successfully, CRISPR/Cas9 editing human iPSCs and differentiating into macrophages has already been performed.110 Protocols now exist for successful differentiation of human iPSCs into vascular SMCs.111–113 While wild-type Cas9 cuts DNA, the advent of endonuclease dead Cas9 (dCas9) allows dCas9 and guide RNAs to target transcriptional activators (eg, dCas9-SAM, dCas9-p300114,115) or transcriptional repressors (eg, dCas9-KRAB [Kruppel-associated box]116) to specific regions of the genome (Figure 2D). This dCas9 transcriptional activation/repression will enable direct perturbation of CAD genes or CAD-associated variants in SMCs. Also, fusion of dCas9 or Cas9 nickase with cytidine or adenine deaminases has allowed for single base pair changes in the genome to be made.117–119 These small perturbations to the DNA sequence, particularly if located in TF binding sites, are sufficient to induce physiologically relevant transcriptional change. For example, a single point mutation in the CArG box in the CNN1 promoter completely ablated expression of this protein in vivo.120 Similarly, a 13bp deletion of a GATA1 (GATA-binding protein 1) binding site in the intronic region of ALAS2 significantly reduced its expression during erythroid cell differentiation.121

Single-Cell Sequencing

Recently, new single-cell technologies, such as single-cell RNA-seq and CyTOF (mass cytometry), have been used to better understand the heterogeneity of the atherosclerotic plaque including heterogeneity within specific immune cell types.122–124 There are now many commercially available and adopted single-cell sequencing systems (eg, 10X Genomics, DropSeq), which involve droplet-based cell capture. So far, with respect to CAD, scRNA-seq has been applied to leukocytes in the plaque such as macrophages but not SMCs. It is expected that scRNA-seq (single-cell RNA-Seq) analysis of human normal and diseased coronary arteries will (1) decipher what CAD candidate genes are co-expressed in cells expressing SMC markers and (2) define different subsets of SMCs in diseased coronary artery that can shed more light on disease pathogenesis (Figure 2E). Similarly, single-cell epigenomics (such as single-cell ATAC-seq) has gained substantial traction recently and can be applied to trace SMC transitions as atherosclerosis progresses.125,126 Single-cell epigenomics also can allow CAD-associated variants to be linked to open chromatin regions (eg, enhancers, promoters) in specific cell types that will facilitate more targeted follow-up functional studies. Finally, integration of single-cell approaches with lineage tracing studies in mice in vivo,127,128 may clarify the precise identity and origin of SMC-derived cells in the atherosclerotic plaque which lack traditional SMC markers.129 Such studies may also improve our understanding of the clonal nature of SMC infiltration and expansion in atherosclerotic plaques.128,130–132

Limitations and Challenges of Genetic Association Studies

It is worth acknowledging the various obstacles in conducting genetic-based association studies for CAD/MI that may confound biological interpretation of the results. For example, quantitation of stable and unstable CAD using angiography still remains a challenge and could produce different results influencing the case definitions of these studies. Also, MI is an equally heterogeneous condition with ≈70% of cases due to plaque rupture, ≈30% due to plaque erosion and a minority due to calcified nodules.133,134 Due to the distinct causes of these pathological phenotypes, the clinical end points may only provide genetic associations for the most prevalent pathology (eg, rupture) while obscuring the others. The impact of demographics, such as age, sex, and ethnicity, while often corrected in these studies, should be specifically addressed to better understand why certain groups are more susceptible to different pathologies (eg, younger women are often more at risk for plaque erosions than rupture).133 It is also worth noting that the widespread use of statins in recent years has led to more MI cases associated with plaque erosion versus rupture,135 thus making it difficult to extrapolate relevant clinical findings from historical cohorts.

It is now well appreciated that the majority of GWAS and QTL based associations represent common variants with modest effects that could impact CAD and related phenotypes over a lifetime. However, human disease manifests through a spectrum of genetic variants and in some individuals CAD susceptibility may be driven by less common alleles with intermediate or large effects that arose through recent ancestors (referred to as Clan Genomics).136 By accounting for the entire catalog of genomic variation in individuals, we can establish the true impact of multiple variants on CAD, and better inform polygenic risk scores for patient stratification and interventional follow-up. Nonetheless, like most genetic discoveries these findings still require experimental functional studies in disease-relevant cell and animal models to elucidate causal genes and mechanisms. Given that many associations mark developmental genes or transition states, it will be important to study these pathways in the appropriate environmental contexts to evaluate their putative functions.

Summary and Perspective

Large-scale genetic studies have uncovered a myriad of new candidate genes with experimental evidence supporting their contributions to vascular functions and CAD risk. However, additional work involving higher resolution assays in other cell types and model systems may be necessary to establish causal mechanisms. Colocalizing GWAS data with molecular quantitative trait locus and other high-throughput multiomics datasets from relevant cells and tissues represents a powerful statistical approach to prioritize causal genes and pathways underlying associations.23,137 Such studies will likely be augmented by other systems-based network analyses to infer directionality of risk loci with upstream and downstream signaling pathways.108 Larger cohorts will likely be required to map transregulatory networks responsible for disease associations.138,139 Complementary CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and perturbation experiments may provide more empirical evidence for candidate genes/pathways impacting disease-relevant phenotypes.140 Nonetheless, CAD remains a complex trait involving interactions of multiple cell types not limited to SMC, including macrophages, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and other immune cells, and intermediate cells. Single-cell sequencing promises to deconstruct novel SMC and non-SMC markers and hierarchies during atherosclerotic phenotypic transitions.26 Integration with in vivo lineage tracing could reconcile some of the controversial origins of these cells in early and advanced lesions. Together, these genetically driven insights into SMC roles may ultimately inform new treatments, biomarkers, or risk stratification for many patients affected by CAD and related diseases.

Highlights.

In this brief review, we highlight several coronary artery disease genome-wide association study loci that harbor genes with functional experimental evidence in smooth muscle cells.

We discuss the power of molecular quantitative trait locus strategies in vascular tissues and cell types to discover genetic regulators of molecular phenotypes and to prioritize genome-wide association study loci.

We also describe studies that utilize quantitative trait locus based network analyses to identify driver genes and interactions across vascular tissues and to predict effects of genetic loci on vascular phenotypes.

We discuss modified CRISPR/dCas9 approaches to target specific regulatory regions at coronary artery disease loci.

Finally, we emphasize single-cell genomic approaches to uncover new cell populations and resolve the heterogeneity of genetic associations.

Sources of Funding

C.L. Miller is supported by a National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award [HL125912] and Leducq Foundation Transatlantic Network of Excellence Award.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ASAP

Advanced Study of Aortic Pathology

- ATAC

assay for transposase accessible chromatin

- BiKE

Biobank of Karolinska Carotid Endarterectomies

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- caQTL

chromatin accessibility quantitative trait locus

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait locus

- GRASP

Genome-Wide Repository of Associations Between SNPs and Phenotypes

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cells

- HCASMC

human coronary artery smooth muscle cells

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cell

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- SMC

smooth muscle cells

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- STAGE

Stockholm Atherosclerosis Gene Expression

- STARNET

Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task

- TF

transcription factor

- TGFB

transforming growth factor β

Footnotes

Visual Overview—An online visual overview is available for this article.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezzati M, Pearson-Stuttard J, Bennett JE, Mathers CD. Acting on non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income tropical countries. Nature. 2018;559:507–516. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0306-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Genetics of coronary artery disease: discovery, biology and clinical translation. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPherson R, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:564–578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Harst P, Verweij N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2018;122:433–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson CP, Goel A, Butterworth AS, et al. ; EPIC-CVD Consortium; CARDIoGRAMplusC4D; UK Biobank CardioMetabolic Consortium CHD Working Group. Association analyses based on false discovery rate implicate new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1385–1391. doi: 10.1038/ng.3913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schunkert H, von Scheidt M, Kessler T, Stiller B, Zeng L, Vilne B. Genetics of coronary artery disease in the light of genome-wide association studies. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018;107(suppl 2):2–9.doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner AW, Wong D, Dreisbach CN, Miller CL. GWAS reveal targets in vessel wall pathways to treat coronary artery disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:72. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motterle A, Pu X, Wood H, Xiao Q, Gor S, Ng FL, Chan K, Cross F, Shohreh B, Poston RN, Tucker AT, Caulfield MJ, Ye S. Functional analyses of coronary artery disease associated variation on chromosome 9p21 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4021–4029. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima Y, Downing K, Kundu R, Miller C, Dewey F, Lancero H, Raaz U, Perisic L, Hedin U, Schadt E, Maegdefessel L, Quertermous T, Leeper NJ. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B regulates efferocytosis and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1083–1097. doi: 10.1172/JCI70391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller CL, Anderson DR, Kundu RK, Raiesdana A, Nürnberg ST, Diaz R, Cheng K, Leeper NJ, Chen CH, Chang IS, Schadt EE, Hsiung CA, Assimes TL, Quertermous T. Disease-related growth factor and embryonic signaling pathways modulate an enhancer of TCF21 expression at the 6q23.2 coronary heart disease locus. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller CL, Haas U, Diaz R, Leeper NJ, Kundu RK, Patlolla B, Assimes TL, Kaiser FJ, Perisic L, Hedin U, Maegdefessel L, Schunkert H, Erdmann J, Quertermous T, Sczakiel G. Coronary heart disease-associated variation in TCF21 disrupts a miR-224 binding site and miRNA-mediated regulation. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sazonova O, Zhao Y, Nürnberg S, Miller C, Pjanic M, Castano VG, Kim JB, Salfati EL, Kundaje AB, Bejerano G, Assimes T, Yang X, Quertermous T. Characterization of TCF21 downstream target regions identifies a transcriptional network linking multiple independent coronary artery disease loci. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurnberg ST, Cheng K, Raiesdana A, et al. Coronary artery disease associated transcription factor TCF21 regulates smooth muscle precursor cells that contribute to the fibrous cap. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner AW, Martinuk A, Silva A, Lau P, Nikpay M, Eriksson P, Folkersen L, Perisic L, Hedin U, Soubeyrand S, McPherson R. Functional analysis of a novel genome-wide association study signal in SMAD3 that confers protection from coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:972–983. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nanda V, Wang T, Pjanic M, et al. Functional regulatory mechanism of smooth muscle cell-restricted LMOD1 coronary artery disease locus. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battle A, Brown CD, Engelhardt BE, Montgomery SB; GTEx Consortium; Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC)—Analysis Working Group; Statistical Methods groups—Analysis Working Group; Enhancing GTEx (eGTEx) groups; NIH Common Fund; NIH/NCI; NIH/NHGRI; NIH/NIMH; NIH/NIDA; Biospecimen Collection Source Site—NDRI; Biospecimen Collection Source Site—RPCI; Biospecimen Core Resource—VARI; Brain Bank Repository—University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank; Leidos Biomedical—Project Management; ELSI Study; Genome Browser Data Integration &Visualization—EBI; Genome Browser Data Integration &Visualization—UCSC Genomics Institute, University of California Santa Cruz; Lead analysts:; Laboratory, Data Analysis &Coordinating Center (LDACC):; NIH program management:; Biospecimen collection:; Pathology:; eQTL manuscript working group. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, et al. ; Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Pjanic M, Wang T, Nguyen T, Gloudemans M, Rao A, Castano VG, Nurnberg S, Rader DJ, Elwyn S, Ingelsson E, Montgomery SB, Miller CL, Quertermous T. Genetic regulatory mechanisms of smooth muscle cells map to coronary artery disease risk loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller CL, Pjanic M, Wang T, et al. Integrative functional genomics identifies regulatory mechanisms at coronary artery disease loci. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12092. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan NT, Whalen MB, Stolze LK, Hadeli NK, Lam MT, Springstead JR, Glass CK, Romanoski CE. Transcriptional networks specifying homeo-static and inflammatory programs of gene expression in human aortic endothelial cells. Elife. 2017;6:e22536. doi: 10.7554/eLife.22536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirka RC, Pjanic M, Quertermous T. Advances in transcriptomics: investigating cardiovascular disease at unprecedented resolution. Circ Res. 2018;122:1200–1220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findley AS, Richards AL, Petrini C, Alazizi A, Doman E, Shanku AG, Davis GO, Hauff NJ, Sorokin Y, Wen X, Pique-Regi R, Luca F. Interpreting coronary artery disease risk through gene-environment interactions in gene regulation. BioRxiv. 2018;475483. doi: 10.1101/475483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler T, Wobst J, Wolf B, et al. Functional characterization of the GUCY1A3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Circulation. 2017;136:476–489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Li P, Zhang Y, Li G-B, Zhou Y-G, Yang K, Dai S-S. c-Ski inhibits the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells via suppressing Smad3 signaling but stimulating p38 pathway. Cell Signal. 2013;25:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lino Cardenas CL, Kessinger CW, Cheng Y, et al. An HDAC9-MALAT1-BRG1 complex mediates smooth muscle dysfunction in thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1009. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03394-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derwall M, Malhotra R, Lai CS, Beppu Y, Aikawa E, Seehra JS, Zapol WM, Bloch KD, Yu PB. Inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein signaling reduces vascular calcification and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:613–622. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas JA, Deaton RA, Hastings NE, Shang Y, Moehle CW, Eriksson U, Topouzis S, Wamhoff BR, Blackman BR, Owens GK. PDGF-DD, a novel mediator of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation, is upregulated in endothelial cells exposed to atherosclerosis-prone flow patterns. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H442–H452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00165.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pontén A, Folestad EB, Pietras K, Eriksson U. Platelet-derived growth factor D induces cardiac fibrosis and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in heart-specific transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2005;97:1036–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190590.31545.d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner AW, Nikpay M, Silva A, Lau P, Martinuk A, Linseman TA, Soubeyrand S, McPherson R. Functional interaction between COL4A1/COL4A2 and SMAD3 risk loci for coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang W, Ng FL, Chan K, et al. Coronary-heart-disease-associated genetic variant at the COL4A1/COL4A2 locus affects COL4A1/COL4A2 expression, vascular cell survival, atherosclerotic plaque stability and risk of myocardial infarction. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer RC, Tohyama J, Cui J, Cheng L, Yang J, Zhang X, Ou K, Paschos GK, Zheng XL, Parmacek MS, Rader DJ, Reilly MP. Knockout of Adamts7, a novel coronary artery disease locus in humans, reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2015;131:1202–1213. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Zheng J, Bai X, Liu B, Liu CJ, Xu Q, Zhu Y, Wang N, Kong W, Wang X. ADAMTS-7 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration and neointima formation in balloon-injured rat arteries. Circ Res. 2009;104:688–698. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pu X, Xiao Q, Kiechl S, et al. ADAMTS7 cleavage and vascular smooth muscle cell migration is affected by a coronary-artery-disease-associated variant. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, et al. ; WTCCC and the Cardiogenics Consortium. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Pennacchio LA, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Magnusson KP, et al. The same sequence variant on 9p21 associates with myocardial infarction, abdominal aortic aneurysm and intracranial aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2008;40:217–224. doi: 10.1038/ng.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hannou SA, Wouters K, Paumelle R, Staels B. Functional genomics of the CDKN2A/B locus in cardiovascular and metabolic disease: what have we learned from GWASs? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarinova O, Stewart AF, Roberts R, Wells G, Lau P, Naing T, Buerki C, McLean BW, Cook RC, Parker JS, McPherson R. Functional analysis of the chromosome 9p21.3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1671–1677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holdt LM, Teupser D. Long noncoding RNA ANRIL: Lnc-ing genetic variation at the chromosome 9p21 locus to molecular mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:145. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2018.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holdt LM, Beutner F, Scholz M, Gielen S, Gäbel G, Bergert H, Schuler G, Thiery J, Teupser D. ANRIL expression is associated with atherosclerosis risk at chromosome 9p21. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:620–627. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holdt LM, Hoffmann S, Sass K, et al. Alu elements in ANRIL non-coding RNA at chromosome 9p21 modulate atherogenic cell functions through trans-regulation of gene networks. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holdt LM, Stahringer A, Sass K, et al. Circular non-coding RNA ANRIL modulates ribosomal RNA maturation and atherosclerosis in humans. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12429. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leeper NJ, Raiesdana A, Kojima Y, et al. Loss of CDKN2B promotes p53-dependent smooth muscle cell apoptosis and aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:e1–e10. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nanda V, Downing KP, Ye J, et al. CDKN2B regulates TGFβ signaling and smooth muscle cell investment of hypoxic neovessels. Circ Res. 2016;118:230–240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lo Sardo V, Chubukov P, Ferguson W, Kumar A, Teng EL, Duran M, Zhang L, Cost G, Engler AJ, Urnov F, Topol EJ, Torkamani A, Baldwin KK. Unveiling the role of the most impactful cardiovascular risk locus through haplotype editing. Cell. 2018;175:1796.e20–1810.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schunkert H, König IR, Kathiresan S, et al. ; Cardiogenics; CARDIoGRAM Consortium. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Acharya A, Baek ST, Huang G, Eskiocak B, Goetsch S, Sung CY, Banfi S, Sauer MF, Olsen GS, Duffield JS, Olson EN, Tallquist MD. The bHLH transcription factor Tcf21 is required for lineage-specific EMT of cardiac fibroblast progenitors. Development. 2012;139:2139–2149. doi: 10.1242/dev.079970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braitsch CM, Combs MD, Quaggin SE, Yutzey KE. Pod1/Tcf21 is regulated by retinoic acid signaling and inhibits differentiation of epicardium-derived cells into smooth muscle in the developing heart. Dev Biol. 2012;368:345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franzén O, Ermel R, Cohain A, et al. Cardiometabolic risk loci share downstream cis- and trans-gene regulation across tissues and diseases. Science. 2016;353:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arab K, Park YJ, Lindroth AM, et al. Long noncoding RNA TARID directs demethylation and activation of the tumor suppressor TCF21 via GADD45A. Mol Cell. 2014;55:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Massagué J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mäkinen VP, Civelek M, Meng Q, et al. ; Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome-Wide Replication And Meta-Analysis (CARDIoGRAM) Consortium. Integrative genomics reveals novel molecular pathways and gene networks for coronary artery disease. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeng L, Dang TA, Schunkert H. Genetics links between transforming growth factor β pathway and coronary disease. Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghosh S, Vivar J, Nelson CP, et al. Systems genetics analysis of genome-wide association study reveals novel associations between key biological processes and coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1712–1722. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iyer D, Zhao Q, Wirka R, Naravane A, Nguyen T, Liu B, Nagao M, Cheng P, Miller CL, Kim JB, Pjanic M, Quertermous T. Coronary artery disease genes SMAD3 and TCF21 promote opposing interactive genetic programs that regulate smooth muscle cell differentiation and disease risk. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hong CY, Gong EY, Kim K, Suh JH, Ko HM, Lee HJ, Choi HS, Lee K. Modulation of the expression and transactivation of androgen receptor by the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Pod-1 through recruitment of histone deacetylase 1. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2245–2257. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kobayashi K, Yokote K, Fujimoto M, Yamashita K, Sakamoto A, Kitahara M, Kawamura H, Maezawa Y, Asaumi S, Tokuhisa T, Mori S, Saito Y. Targeted disruption of TGF-beta-Smad3 signaling leads to enhanced neointimal hyperplasia with diminished matrix deposition in response to vascular injury. Circ Res. 2005;96:904–912. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163980.55495.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Howson JMM, Zhao W, Barnes DR, et al. ; CARDIoGRAMplusC4D; EPIC-CVD. Fifteen new risk loci for coronary artery disease highlight arterial-wall-specific mechanisms. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1113–1119. doi: 10.1038/ng.3874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nanda V, Miano JM. Leiomodin 1, a new serum response factor-dependent target gene expressed preferentially in differentiated smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2459–2467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Halim D, Wilson MP, Oliver D, et al. Loss of LMOD1 impairs smooth muscle cytocontractility and causes megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome in humans and mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E2739–E2747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620507114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perisic Matic L, Rykaczewska U, Razuvaev A, et al. Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis is associated with downregulation of LMOD1, SYNPO2, PDLIM7, PLN, and SYNM. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1947–1961. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gilad Y, Rifkin SA, Pritchard JK. Revealing the architecture of gene regulation: the promise of eQTL studies. Trends Genet. 2008;24:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cookson W, Liang L, Abecasis G, Moffatt M, Lathrop M. Mapping complex disease traits with global gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:184–194. doi: 10.1038/nrg2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Albert FW, Kruglyak L. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:197–212. doi: 10.1038/nrg3891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Björkegren JLM, Kovacic JC, Dudley JT, Schadt EE. Genome-wide significant loci: how important are they? Systems genetics to understand heritability of coronary artery disease and other common complex disorders. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:830–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van der Laan SW, Siemelink MA, Haitjema S, et al. ; METASTROKE Collaboration of the International Stroke Genetics Consortium. Genetic susceptibility loci for cardiovascular disease and their impact on atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11:e002115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Talukdar HA, Foroughi Asl H, Jain RK, et al. Cross-tissue regulatory gene networks in coronary artery disease. Cell Syst. 2016;2:196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Folkersen L, Persson J, Ekstrand J, Agardh HE, Hansson GK, Gabrielsen A, Hedin U, Paulsson-Berne G. Prediction of ischemic events on the basis of transcriptomic and genomic profiling in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Mol Med. 2012;18:669–675. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Folkersen L, van’t Hooft F, Chernogubova E, Agardh HE, Hansson GK, Hedin U, Liska J, Syvänen AC, Paulsson-Berne G, Paulssson-Berne G, Franco-Cereceda A, Hamsten A, Gabrielsen A, Eriksson P; BiKE and ASAP Study Groups. Association of genetic risk variants with expression of proximal genes identifies novel susceptibility genes for cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:365–373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.948935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Erbilgin A, Civelek M, Romanoski CE, Pan C, Hagopian R, Berliner JA, Lusis AJ. Identification of CAD candidate genes in GWAS loci and their expression in vascular cells. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1894–1905. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krause MD, Huang RT, Wu D, Shentu TP, Harrison DL, Whalen MB, Stolze LK, Di Rienzo A, Moskowitz IP, Civelek M, Romanoski CE, Fang Y. Genetic variant at coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke locus 1p32.2 regulates endothelial responses to hemodynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E11349–E11358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810568115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hauberg ME, Zhang W, Giambartolomei C, Franzén O, Morris DL, Vyse TJ, Ruusalepp A, Sklar P, Schadt EE, Björkegren JLM, Roussos P; CommonMind Consortium. Large-scale identification of common trait and disease variants affecting gene expression. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li YI, van de Geijn B, Raj A, Knowles DA, Petti AA, Golan D, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. RNA splicing is a primary link between genetic variation and disease. Science. 2016;352:600–604. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eicher JD, Landowski C, Stackhouse B, Sloan A, Chen W, Jensen N, Lien J-P, Leslie R, Johnson AD. GRASP v2.0: an update on the Genome-Wide Repository of Associations between SNPs and phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D799–D804. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foroughi Asl H, Talukdar HA, Kindt AS, et al. ; CARDIoGRAM Consortium. Expression quantitative trait Loci acting across multiple tissues are enriched in inherited risk for coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:305–315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhong H, Beaulaurier J, Lum PY, et al. Liver and adipose expression associated SNPs are enriched for association to type 2 diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rotival M, Zeller T, Wild PS, et al. ; Cardiogenics Consortium. Integrating genome-wide genetic variations and monocyte expression data reveals trans-regulated gene modules in humans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brænne I, Civelek M, Vilne B, et al. ; Leducq Consortium CAD Genomics‡. Prediction of causal candidate genes in coronary artery disease loci. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2207–2217. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Romanoski CE, Lee S, Kim MJ, Ingram-Drake L, Plaisier CL, Yordanova R, Tilford C, Guan B, He A, Gargalovic PS, Kirchgessner TG, Berliner JA, Lusis AJ. Systems genetics analysis of gene-by-environment interactions in human cells. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fairfax BP, Humburg P, Makino S, Naranbhai V, Wong D, Lau E, Jostins L, Plant K, Andrews R, McGee C, Knight JC. Innate immune activity conditions the effect of regulatory variants upon monocyte gene expression. Science. 2014;343:1246949. doi: 10.1126/science.1246949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim-Hellmuth S, Bechheim M, Pütz B, et al. Genetic regulatory effects modified by immune activation contribute to autoimmune disease associations. Nat Commun. 2017;8:266. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00366-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Degner JF, Pai AA, Pique-Regi R, Veyrieras JB, Gaffney DJ, Pickrell JK, De Leon S, Michelini K, Lewellen N, Crawford GE, Stephens M, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. DNase I sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature. 2012;482:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kasowski M, Kyriazopoulou-Panagiotopoulou S, Grubert F, et al. Extensive variation in chromatin states across humans. Science. 2013;342:750–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1242510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McVicker G, van de Geijn B, Degner JF, Cain CE, Banovich NE, Raj A, Lewellen N, Myrthil M, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Identification of genetic variants that affect histone modifications in human cells. Science. 2013;342:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1242429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Mullikin JC, Tai D, Blakesley R, Bouffard G, Young A, Masiello C, Green ED, Wolfsberg TG, Collins FS; National Institutes Of Health Intramural Sequencing Center. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genome-wide recovery of DNase hypersensitive sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:992–997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307540100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Whittle J, et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS). Genome Res. 2006;16:123–131. doi: 10.1101/gr.4074106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Furey TS, Crawford GE. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell. 2008;132:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu C, Huang RT, Kuo CH, et al. Mechanosensitive PPAP2B regulates endothelial responses to atherorelevant hemodynamic forces. Circ Res. 2015;117:e41–e53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.306457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.van de Geijn B, McVicker G, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. WASP: allele-specific software for robust molecular quantitative trait locus discovery. Nat Methods. 2015;12:1061–1063. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kumasaka N, Knights AJ, Gaffney DJ. Fine-mapping cellular QTLs with RASQUAL and ATAC-seq. Nat Genet. 2016;48:206–213. doi: 10.1038/ng.3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moyerbrailean GA, Kalita CA, Harvey CT, Wen X, Luca F, Pique-Regi R. Which genetics variants in DNase-Seq footprints are more likely to alter binding? PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mumbach MR, Rubin AJ, Flynn RA, Dai C, Khavari PA, Greenleaf WJ, Chang HY. HiChIP: efficient and sensitive analysis of protein-directed genome architecture. Nat Methods. 2016;13:919–922. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Javierre BM, Burren OS, Wilder SP, et al. ; BLUEPRINT Consortium. Lineage-specific genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell. 2016;167:1369.e19–1384.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mumbach MR, Satpathy AT, Boyle EA, et al. Enhancer connectome in primary human cells identifies target genes of disease-associated DNA elements. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1602–1612. doi: 10.1038/ng.3963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yao C, Chen G, Song C, et al. Genome-wide mapping of plasma protein QTLs identifies putatively causal genes and pathways for cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3268. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05512-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McRae AF, Marioni RE, Shah S, et al. Identification of 55,000 replicated DNA methylation QTL. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17605. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35871-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van der Laan SW, Foroughi Asl H, van den Borne P, van Setten J, van der Perk ME, van de Weg SM, Schoneveld AH, de Kleijn DP, Michoel T, Björkegren JL, den Ruijter HM, Asselbergs FW, de Bakker PI, Pasterkamp G. Variants in ALOX5, ALOX5AP and LTA4H are not associated with atherosclerotic plaque phenotypes: the Athero-Express Genomics Study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:528–538. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao Y, Chen J, Freudenberg JM, Meng Q, Rajpal DK, Yang X. Network-based identification and prioritization of key regulators of coronary artery disease loci. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:928–941. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lempiäinen H, Brænne I, Michoel T, et al. Network analysis of coronary artery disease risk genes elucidates disease mechanisms and druggable targets. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3434. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20721-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chadwick AC, Musunuru K. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing for treatment of atherogenic dyslipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:12–18. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang H, Shi J, Hachet MA, Xue C, Bauer RC, Jiang H, Li W, Tohyama J, Millar J, Billheimer J, Phillips MC, Razani B, Rader DJ, Reilly MP. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human iPSC-derived macrophage reveals lysosomal acid lipase function in human macrophages-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:2156–2160. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ayoubi S, Sheikh SP, Eskildsen TV. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells: differentiation and therapeutic potential. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:1282–1293. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maguire EM, Xiao Q, Xu Q. Differentiation and application of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:2026–2037. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dash BC, Jiang Z, Suh C, Qyang Y. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells: methods and application. Biochem J. 2015;465:185–194. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hilton IB, D’Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, Gersbach CA. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Joung J, Konermann S, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Platt RJ, Brigham MD, Sanjana NE, Zhang F. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and transcriptional activation screening. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:828–863. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shimatani Z, Kashojiya S, Takayama M, Terada R, Arazoe T, Ishii H, Teramura H, Yamamoto T, Komatsu H, Miura K, Ezura H, Nishida K, Ariizumi T, Kondo A. Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:441–443. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Adli M The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04252-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Han Y, Slivano OJ, Christie CK, Cheng AW, Miano JM. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing of a single regulatory element nearly abolishes target gene expression in mice–brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:312–315. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang Y, Zhang J, An W, Wan Y, Ma S, Yin J, Li X, Gao J, Yuan W, Guo Y, Engel JD, Shi L, Cheng T, Zhu X. Intron 1 GATA site enhances ALAS2 expression indispensably during erythroid differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:657–671. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]