Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted rapid and innovative policymaking around the world at the national, regional, and local levels. There has been limited work to systematically document and characterize new and expanded local U.S. pandemic-era policies, which is imperative to better understand the policy variation and resulting health impacts during this unprecedented time. California, the most populous U.S. state, provides a case example of a particularly active policy response. The aim of this Brief Report is to summarize the creation and potential areas of application of a newly created publicly available California- and US-based COVID-19 policy database. We generated an extensive list of California and US policies that were modified or created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. From July–November 2021, we searched current and historical California and federal government websites, press releases, social media, and news sources and recorded detailed information on these policies, including coverage dates, eligibility criteria, and benefit amounts. This comprehensive dataset includes 39 public health, economic, housing, and safety net programs and policies implemented at both federal and state levels and provides details of the complex and multifaceted policy landscape in California from March 2020 to November 2021. Our database is publicly available. Future investigators can leverage the information systematically recorded in this database to rigorously assess the short- and long-term effects of these policies, which will in turn inform future preparedness response plans in California and beyond.

Keywords: COVID-19, public health policy, socioeconomic factors, government, safety net, health disparities, California, economic transition

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated mitigating measures have fundamentally changed daily life on a global scale. In the United States, the pandemic has further exacerbated pre-existing racial and socioeconomic disparities in health, with minoritized racial/ethnic and low-income populations more likely to be infected, die, or suffer economic consequences [1,2]. Social and economic policies have the potential to alleviate health inequities [3,4,5,6], and these most recent disparities underscore the need for policies to address disproportionate adverse effects on vulnerable groups.

Accordingly, the pandemic has prompted rapid policymaking in many countries across the globe at the national, regional, and local governmental levels [7], including the United States [8]. The state of California— the second-most diverse U.S. state [9], in which 1 in 8 Americans live—has been particularly active in its COVID-19 policy response: it was the first to implement a statewide shelter-in-place order in March 2020 and to mandate vaccines for teachers and healthcare workers in August 2021 [10]. The state has also been at the forefront of social and economic policies to prevent and address pandemic-related disparities, including the creation and expansion of numerous safety net programs [11]. This is particularly important given California’s high poverty rate (16.4%, compared with the national average of 10.5%) and the high COVID-19 death and case rates among low-income and communities of color [1,12].

These disparities highlight the urgent need for rigorous assessment of current pandemic-related programs and policies to evaluate which were most salient for vulnerable groups. Systematically documenting new and expanded pandemic-era policies can help assess policies’ health impacts. However, to our knowledge, only two publicly available databases capture variation in COVID-19-related policies. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) compiles policies related to economics, containment, and health for 180 countries and most US states [7]. OxCGRT focuses on public health mitigation but does not include many relevant economic and safety net policies. Additionally, the COVID-19 US State Policy database (CUSP) at Boston University captures state policies related to COVID-19 prevention, economic precarity, and health equity does not include U.S. federal policies [8].

The current study addresses this critical knowledge gap through the creation of a comprehensive dataset that systematically documents policy changes across four categories relevant to health and social equity during the pandemic. This database is publicly available, enabling researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders to rigorously assess the short- and long-term effects of these policies and inform future preparedness response plans in California and beyond.

2. Materials and Methods

We generated a comprehensive database to capture the policy landscape of California during the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 to November 2021. First, we generated a list of California and federal policies based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) The policy/program had been modified or created in response to COVID-19 or in response to pandemic-related social or economic hardships; (2) the policy/program was enacted in the state of California or at the federal level and was implemented in California; and (3) the selected programs/policies fell into one of four domains: (1) COVID-19 mitigation; (2) safety net; (3) housing; and (4) school/childcare. These categories were chosen given their relevance to health and social equity and their integral role in achieving healthier and more equitable communities, as documented in prior literature [13].

Next, from July-November 2021, we searched California and federal government websites for programs and policies of interest and systematically documented the following information. For each policy we found: what changes occurred, when these changes occurred, whether the policy was implemented at the national or state level, relevant legislative documentation, announcement dates, coverage dates, eligibility criteria, and benefit amounts. One methodological innovation of this study leveraged an established digital archive tool, the Wayback Machine [14], to better collect and document historical data from archived versions of government websites. When websites only provided current policy data and had removed outdated information, we used the Wayback Machine to access archived versions of these websites. This tool allowed us to create a more robust longitudinal policy database, even when searching for data on programs which had changed multiple times or even expired. When government web pages did not exist or did not provide the relevant program details required for our database, we used the search engine Google to find press releases, social media posts from official sources (e.g., governmental organizations), and news sources from the time of the policy change. Search terms included names and acronyms of a program/policy and restriction of the search date range to 1 month before and 1 month after the program/policy change of interest. The search term “California” was included when searching for information on state-level policies. For documentation and replication purposes, our team archived all websites used for this database that were not already archived by The Wayback Machine, avoiding the potential loss of relevant policy information in this rapidly evolving policy environment. Current and historical citations for each policy were embedded in the database itself. To ensure quality and validity of our work, three data collectors independently reviewed the information included in the dataset and all abstracted policy details using identified citations. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved between data collectors.

After the database had been compiled, we tabulated the number of policies in each domain and plotted them on a timeline to examine temporal trends in policy enactment.

3. Results

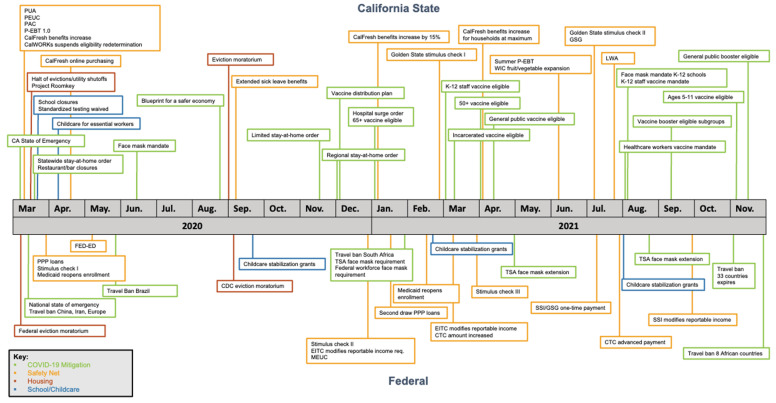

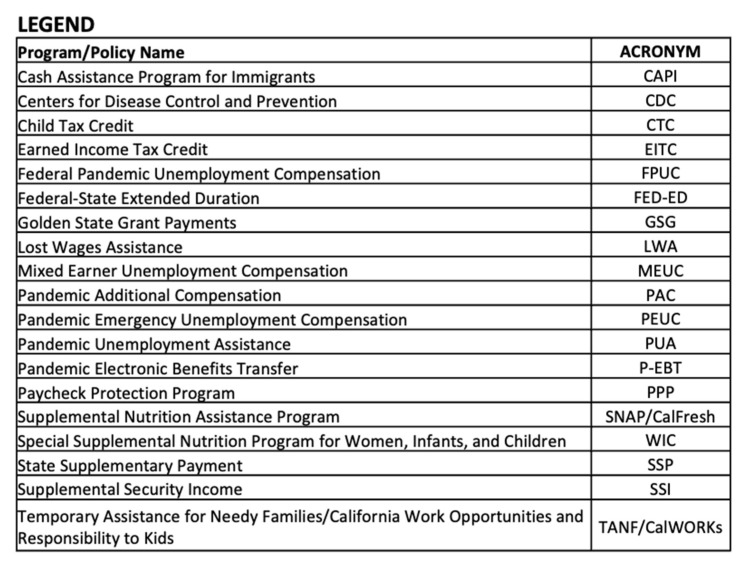

We identified and collected data on 39 federal and California state programs and policies, including 11 COVID-19 mitigation policies, 20 safety net policies, 4 school/childcare policies, and 4 housing policies (Supplemental Table S1). Figure 1 provides a timeline of these policies, demonstrating that numerous California and federal policies were implemented concurrently with the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. As the pandemic progressed, many existing safety net programs were expanded (e.g., unemployment benefits), and new programs were formed (e.g., the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer program) to continue to address evolving needs, although many have since expired.

Figure 1.

Timeline of California and federal implementation of COVID-19-related programs and policies relevant to vulnerable populations, March 2020 to November 2021.

The database also illustrates that the policy landscape was constantly changing during this time period. For example, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, known as CalFresh in California) increased monthly allotments three times under different eligibility criteria between March 2020 and April 2021 (Supplemental Table S1). Three different stay-at-home orders were implemented in California, in addition to a tiered re-opening strategy—the “Blueprint”—guiding counties in their policymaking based on local COVID-19 burden (Supplemental Table S1). These examples, among others, highlight that just within the state of California, unique populations were differentially impacted by this rapidly changing and diverse policy landscape.

Interested investigators can also access the full database and associated documentation in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/SPHERE-UCSF/CA_COVID-19_Policy_Landscape) (accessed on 24 February 2022).

4. Discussion

This study synthesized both federal level and state level policy changes that were intended to alleviate the health and economic consequences of the pandemic in California. In a novel database that we made publicly available, we documented a rich policy landscape with numerous policies intended to address disease transmission and others addressing multiple social determinants of health that were impacted by the pandemic, including income, housing, food security, and employment [15,16]. Notably, we found few school/childcare policies created or expanded during the first two years of the pandemic compared with other policy categories. This apparent shortage of programs may explain why childcare has been a continuing challenge for families and in women in particular as the pandemic has progressed [17].

Our documentation of this rapidly changing policy landscape can be used in future policy evaluations to investigate the downstream health implications of pandemic-related state and federal policies. Such analyses are imperative for governments as they continue to confront additional COVID-19 surges and prepare for future public health emergencies, all while assuring health equity. This database provides the basis for such analysis in California and should be leveraged for future policy analyses or form the basis for policy data collection in other U.S. states or countries. Furthermore, documenting the dynamic and multiple changes to policies over time during the pandemic helps to illustrate the ongoing uncertainty and fluid nature of support provided during an unstable time. Future studies should assess the effects of these many changes on the intended beneficiaries of the policies.

Some policy evaluations conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic reported mixed effects of public policies on physical and mental health. For example, local stay-at-home orders were associated with increased depression/anxiety [4], while receipt of pandemic unemployment insurance was associated with fewer symptoms of depression/anxiety and reduced healthcare delays [18]. Results of studies like these that focused on individual policies need to be interpreted in the context of the multiple co-occurring policies that we document here to account for possible confounding; that is, our database will help place these studies in the larger context of federal and state COVID-19-related policymaking in which individual policies occurred [19].

Limitations

This database is not an exhaustive dataset of all policy changes across all sectors of government in California and nationally, but rather, a presentation of COVID-19-related policy changes at the state and federal level that are relevant to health and social equity in California during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the federal policies included in our database are still relevant for vulnerable groups in other states, and this database can be used in conjunction with OxCGRT and CUSP to create a more holistic picture of the policy landscape during this period. Additionally, due to heterogeneity in policy implementation locally, future work should also document policy changes at county or city levels. Finally, this database captures policy implementation rather than real-world enforcement (e.g., program take-up or adherence).

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the critical nexus between public policy and public health and the implications that policy change has for public health and health inequities. We provide documentation of COVID-19-related policies in the most populous U.S. state, California, including mitigation measures related to COVID-19, as well as social policies to address the economic fallout. The granular detail we document in this database can form the basis for analyses that leverage variation to assess the health effects of COVID-19-related policies on a wide array of health outcomes [20,21,22]. This evidence will enable future policy evaluations to quantify the impact of policy changes on health disparities and inform potential interventions to address inequities.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://github.com/SPHERE-UCSF/CA_COVID-19_Policy_Landscape (accessed on 24 February 2022).

Author Contributions

R.H., W.G. and L.C.H.F. provided strategic oversight in conceptualization and methodology, including formulating the study design and generation of policies to include in the publicly available database. R.H., W.G. and L.C.H.F. supervised this study. K.E.J. contributed to project administration, methodology of data collection, data curation, validation of data, data visualization, and drafting of the initial manuscript. K.E.J., R.H., W.G. and L.C.H.F. contributed to writing the original draft. J.Y. completed primary data curation and validation. K.E.J., R.H. and J.Y. completed quality and validity checks of the policy database. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers U01-MH129968 and 3R01AG063385-03S1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

A publicly available dataset was created in this study. This data can be found here: https://github.com/SPHERE-UCSF/CA_COVID-19_Policy_Landscape (accessed on 24 February 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

Kaitlyn Jackson has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Joseph Yeb has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Rita Hamad has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Wendi Gosliner has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Lia Fernald has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.California’s Commitment to Health Equity. [(accessed on 5 January 2022)]; Available online: https://covid19.ca.gov/equity/

- 2.Anderson A. Women and People of Color Take Biggest Hits in California’s Job Losses. California Budget & Policy Center; Sacramento, CA, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer C.B., Adrien N., Silguero J.J., Hopper J.J., Chowdhury A.I., Werler M.M. Mask adherence and rate of COVID-19 across the United States. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0249891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marroquin B., Vine V., Morgan R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113419. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields-Zeeman L., Collin D.F., Batra A., Hamad R. How does income affect mental health and health behaviours? A quasi-experimental study of the earned income tax credit. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2021;75:929–935. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molitor F., Doerr C. Very Low Food Security Among Low-Income Households with Children in California Before and Shortly After the Economic Downturn From COVID-19. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E01. doi: 10.5888/pcd18.200517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., Webster S., Cameron-Blake E., Hallas L., Majumdar S., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021;5:5299–5538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raifman J.N.K., Jones D., Bor J., Lipson S., Jay J., Chan P. COVID-19 US State Policy Database. [(accessed on 13 September 2021)]. Available online: www.tinyurl.com/statepolicies.

- 9.Census: Racial and Ethnic Diversity Index by State. [(accessed on 6 February 2022)];2020 Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2021/dec/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-index.html.

- 10.California Implements First-in-the-Nation Measure to Encourage Teachers and School Staff to Get Vaccinated. [(accessed on 6 January 2022)]; Available online: https://www.gov.ca.gov/2021/08/11/california-implements-first-in-the-nation-measure-to-encourage-teachers-and-school-staff-to-get-vaccinated/

- 11.Benefit Increases Because of COVID-19. [(accessed on 6 January 2022)]. Available online: http://calfresh.guide/benefit-increase-because-of-covid-19/

- 12.Bohn S., Danielson C., Thorman T. Poverty in California. Public Policy Institute of California; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berenson J., Yan L., Lynch J., Pagán J.A. Identifying Policy Levers and Opportunities For Action Across States to Achieve Health Equity. Health Aff. 2017;36:1048–1056. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Internet Archive the Wayback Machine. [(accessed on 13 May 2021)]. Available online: https://web.archive.org/

- 15.Raifman J., Bor J., Venkataramani A. Association Between Receipt of Unemployment Insurance and Food Insecurity Among People Who Lost Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2035884. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory Acs M.K. Employment, Income, and Unemployment Insurance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Urban Institute; Washington, DC, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins C., Landivar L.C., Ruppanner L., Scarborough W.J. COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours. Gend. Work. Organ. 2020;28:101–112. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkowitz S.A., Basu S. Unmet Social Needs and Worse Mental Health After Expiration Of COVID-19 Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation. Health Aff. 2021;40:426–434. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthay E.C., Hagan E., Joshi S., Tan M.L., Vlahov D., Adler N., Glymour M.M. The revolution will be hard to evaluate: How co-occurring policy changes affect research on the health effects of social policies. Epidemiol. Rev. 2021;43:19–32. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food D.G.E. Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Washington, DC, USA: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bianchi F., Bianchi G., Song D. The Long-Term Impact of the COVID-19 Unemployment Shock on Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2021. Working paper 18304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Been J.V., Burgos Ochoa L., Bertens L.C.M., Schoenmakers S., Steegers E.A.P., Reiss I.K.M. Impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth: A national quasi-experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e604–e611. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30223-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

A publicly available dataset was created in this study. This data can be found here: https://github.com/SPHERE-UCSF/CA_COVID-19_Policy_Landscape (accessed on 24 February 2022).