Abstract

The metacestode stage of Echinococcus multilocularis is the causative agent of alveolar echinococcosis (AE), a parasitic disease affecting the liver, with occasional metastasis into other organs. Benzimidazole carbamate derivatives such as mebendazole and albendazole are currently used for chemotherapeutic treatment of AE. Albendazole is poorly resorbed and is metabolically converted to its main metabolite albendazole sulfoxide, which is believed to be the active component, and further to albendazole sulfone. Chemotherapy with albendazole has been shown to have a parasitostatic rather than a parasitocidal effect; it is not effective in all cases, and the recurrence rate is rather high once chemotherapy is stopped. Thus, development of new means of chemotherapy of AE is needed. This could include modifications of benzimidazoles and elucidiation of the respective biological pathways. In this study we performed in vitro drug treatment of E. multilocularis metacestodes with albendazole sulfoxide and albendazole sulfone. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of vesicle fluids showed that the drugs were taken up rapidly by the parasite. Transmission electron microscopic investigation of parasite tissues and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of vesicle fluids demonstrated that albendazole sulfoxide and albendazole sulfone had similar effects with respect to parasite ultrastructure and changes in metabolites in vesicle fluids. This study shows that the in vitro cultivation model presented here provides an ideal first-round test system for screening of antiparasite drugs.

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is prevalent in many areas of the Northern Hemisphere. In regions where the disease is endemic, such as Alaska, Central Europe, and Japan, it is well known as a public health hazard to humans (31). The disease, which is caused by the metacestode (larval) stage of Echinococcus multilocularis, is one of the most lethal helminthic infections of humans. The adult tapeworm exists as an enteric parasite in the fox and in a few other carnivores, such as the wolf, cat, and dog. The gravid proglottids produce round to ovoid eggs (30 to 36 μm in diameter), each containing a single, fully differentiated oncosphere. These are shed into the environment with the feces, and when they are ingested by a suitable intermediate host, or accidentally by humans, digestive processes and other factors in the host gut result in hatching and release of the oncosphere. The oncosphere actively penetrates the epithelial border of the intestinal villi and enters venous and lymphatic vessels to finally reach the liver, where maturation to the asexually proliferating metacestode takes place. Growth of these larvae causes massive lesions in the liver and occasionally in secondarily infected organs such as the lung and brain, often with fatal consequences for the patient (15).

Benzimidazole carbamate derivatives such as mebendazole and albendazole are currently used for chemotherapeutic treatment of AE as well as of cystic hydatid disease, which is caused by the closely related cestode parasite Echinococcus granulosus. However, in contrast to the case for cystic hydatid disease (34), these treatments alone are not sufficient to cure AE (12, 14, 26, 27). The only curative treatment of AE is still radical surgical resection of the parasite tumor, supported by pre- and postoperative chemotherapy (3, 20). The heterogeneity of the polycystic larvae, including foci of regression, actively proliferating tissue, sites of necrosis, and secondary complications, all intermingled within a tumor-like parasitic mass, severely complicates the assessment of the course of the disease. Treatment with albendazole normally extends over a period of many years (23). When treatment is stopped, a recurrence of parasite growth has been observed in many patients, indicating that its proliferation has only been inhibited and that the parasite has in fact survived the treatment (1, 2, 44).

No information on the actual drug concentration within the actual parasite compartments during chemotherapeutic treatment has been conclusively obtained. Albendazole is normally not detectable in human plasma, since it is rapidly metabolized to its major active metabolite, albendazole sulfoxide (ABZSO), which can be quantitatively determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (45). The second metabolite, albendazole sulfone (ABZSN), has been suggested to have no antiparasite activity (10). In vitro cultivation procedures for long-term proliferation and growth of individual E. multilocularis metacestodes have been established by Hemphill and Gottstein (17, 18) and by Jura et al. (22). These in vitro-generated metacestodes are basically identical to metacestodes produced in mice or gerbils but can be easily manipulated without interfering with host components, and they therefore represent an excellent system for parasite-oriented studies (21, 22, 25, 38).

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the suitability of this system for investigation of the in vitro efficacy of the albendazole metabolites ABZSO and ABZSN against E. multilocularis metacestodes. By HPLC analysis of vesicle fluid fractions, we determined the efficiency of ABZSO uptake in vitro, and drug-induced ultrastructural changes were demonstrated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We found that both ABZSO and ABZSN exhibited a parasitocidal effect on the parasites in vitro. Metabolic changes during drug treatment were monitored by analyzing vesicle fluid by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. This was performed with the goal of providing basic parameters which may contribute to improve the performance of the less sensitive in vivo NMR spectroscopy, which is currently being evaluated to identify AE tumors, and to monitor the progress of chemotherapy in human AE patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design.

In order to investigate the direct effects on and changes to E. multilocularis metacestodes due to drug treatment, the following experimental approach was used: (i) cultivation of E. multilocularis metacestodes in vitro and selection of actively growing and proliferating vesicles, (ii) incubation of metacestodes in medium containing defined amounts of ABZSO and ABZSN, (iii) harvesting of vesicles at defined time points and separation of vesicle fluid and metacestode tissue, (iv) determination of the kinetics of drug uptake by HPLC analysis of ABZSO and ABZSN in vesicle fluid, (v) investigation of the morphological and ultrastructural alterations to metacestodes due to drug treatment, and (vi) monitoring of detectable metabolic changes within vesicle fluid by 1H NMR analysis.

Biochemicals.

If not otherwise stated, all reagents and tissue culture media were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Zürich, Switzerland).

In vitro cultivation of parasites.

In vitro cultivation of E. multilocularis metacestodes was carried out as described previously (17). Briefly, gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) were infected intraperitoneally with the E. multilocularis clone KF5. After 1 to 2 months, the animals were euthanized, and the parasite tissue was recovered from the peritoneal cavity under aseptic conditions. The tissue pieces were cut into small tissue blocks (0.5 cm3), and these were washed twice in Hanks balanced salt solution. Two pieces of tissue were placed in 40 ml of culture medium (RPMI 1640 containing 12 mM HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 200 U of penicillin/ml, 200 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 0.50 μg of amphotericin B [Fungizone]/ml). The tissue blocks were kept in tightly closed culture flasks (75 cm2) placed in an upright position in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2, with medium changes every 2 to 4 days.

Drug treatments and isolation of in vitro-generated metacestode vesicle walls and vesicle fluids.

Intact vesicles 1 to 5 mm in diameter were harvested after 3 to 4 weeks of cultivation. The time of vesicle collection was selected such as to obtain actively growing and proliferating parasites. The metacestodes were pooled and divided again into separate cultures with approximately 150 vesicles in 50 ml of fresh growth medium. ABZSO and ABZSN (kindly provided by R. J. Horten, SmithKline Beecham, London, United Kingdom) were prepared as stock solutions of 10 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). These reagents were added to the cultures at a 1:1,000 dilution, yielding a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. For each experiment, the appropriate controls included (i) a culture containing an equal amount of DMSO and (ii) a culture in growth medium alone. The parasites were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2, and at defined time points as indicated in Fig. 1, approximately 10 to 20 vesicles were carefully removed and washed twice in distilled water. The water was carefully aspirated, and the tube containing the vesicles was placed on ice. The metacestodes were then gently broken up by using a pipette, and the preparation was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant (containing vesicle fluid) was collected and spun again at 10,000 × g at 4°C, and the samples were stored at −80°C before further use. The pellets (representing the metacestode tissues) were carefully collected and processed for TEM as described below.

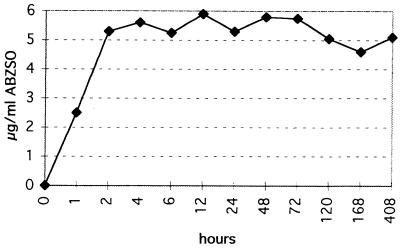

FIG. 1.

Time course of ABZSO content in vesicle fluids of E. multilocularis metacestodes isolated at different time points during cultivation in the presence of 10 μg of ABZSO per ml.

TEM.

Freshly isolated vesicle walls were processed for TEM (17). Briefly, they were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer for 4 h at room temperature, followed by postfixation in 2% OsO4 in phosphate buffer. Samples were extensively washed in distilled water and were incubated in 1% uranyl acetate for 1 h at 4°C, followed by several washes in buffer. They were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions and subsequently embedded in Epon 812 resin as described by Hemphill and Croft (19). Polymerization of the resin was carried out at 65°C overnight. Sections were cut on a Reichert and Jung ultramicrotome and were loaded onto 300-mesh copper grids (Plano GmbH, Marburg, Germany). Staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate was performed as described previously (19).

HPLC analysis.

HPLC analyses were performed with a modification of the procedure reported by Zeugin et al. (45), using a model 510 pump (Waters Associated, Milford, Mass.), a model 717plus autosampler (Waters), an RP-18 (7-μm) Nucleosil column (250/8/4; Macherey Nagel, Oensingen, Switzerland), and a model UV2000 detector (Spectra Physics, San Jose, Calif.). The detection wavelength was set to 230 nm. The mobile phase was prepared from a mixture of 5 mM aqueous potassium dihydrogen phosphate (pH adjusted to 6.5 with a few drops of 20% KOH) and acetonitrile (68:32, vol/vol). The flow rate was 0.7 ml/min and the temperature was ambient. Quantitation was based on six-level internal calibration by using peak areas. Calibrator samples (concentration range, 0.1 to 2.25 μg/ml) and control samples (1.4 μg/ml) were prepared in Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate buffer containing 60 mg of purified bovine serum albumin per ml. Prior to extraction, 100 μl of vesicle fluid was diluted with 400 μl of saline. Aliquots of 0.5 ml of sample (diluted vesicle fluid, calibrators, and controls) were mixed with 25 μl of internal standard solution (methanolic solution of cyclobendazole, about 22.5 μg/ml), 500 ml of 0.25 M (pH 10.3) sodium carbonate buffer, and 5 ml of dichloromethane for 10 min by using a capped glass tube and a horizontal shaker. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g, the aqueous (upper) phase was discarded and the organic phase was transferred to a clean test tube, evaporated to dryness (37°C under air), and reconstituted in 200 μl of methanol. For analysis, aliquots of 25 μl were injected. By analyzing controls, extraction recoveries for ABZSO and ABZSN were determined to be 66% (n = 3) and 77% (n = 3), respectively, and the interday reproducibility was 3.2% (n = 8). The assay detection limits for ABZSO and ABZSN in the samples were 0.05 mg/ml each. Thus, the detection limit for the assessed vesicle fluids was about 0.25 μg/ml.

NMR analysis.

Equal amounts (100 μl) of vesicle fluid collected after defined times of incubation and prepared as described above were added to equal amounts (300 μl) of D2O and were then transferred into 5-mm NMR tubes for 1H NMR analysis. One-dimensional 1H NMR spectra were acquired with a 500-MHz spectrometer (Bruker DRX500). To suppress the residual strong H2O signal at 4.8 ppm, presaturation prior to acquisition was applied for 4 s. Identical acquisition and processing parameters were used throughout. Data processing and plotting were set up in the absolute-intensity mode, allowing spectral comparison and interpretation to be performed in a most convenient and direct way. The intense, well-resolved, and for the subsequent interpretation most-promising peaks of succinate (2.37 ppm), acetate (1.88 ppm), alanine (1.43 ppm), and lactate (1.30 ppm) were selected, and their evolution over time was indirectly monitored by measuring 12 vesicle fluids sampled at different times of incubation, ranging from 1 to 16 days. These most-intense peaks had also been selected in view of the less sensitive in vivo NMR spectroscopy currently being evaluated to identify AE tumors and to monitor the progress of chemotherapy in human AE patients.

RESULTS

Morphological observations.

In a first series of experiments, the morphological effects of in vitro treatment of E. multilocularis metacestodes in the presence of 10 μg of either ABZSO or ABZSN per ml were observed. This drug concentration has been previously used to investigate morphological and ultrastructural alterations in E. granulosus protoscoleces (8, 30). During the first 3 days of incubation, vesicles in all cultures remained intact, with no loss of turgidity. On day 5, considerable loss of turgidity was observed in the drug-treated cultures, with 30 to 40% of vesicles being affected. No damage could be seen in any of the control vesicles. At day 10, most (>90%) of the vesicles were damaged upon drug treatment, and control vesicles still showed no alterations. At the end of the incubation period (day 16), all drug-treated metacestodes exhibited clear signs of distortion, while in control cultures no damage could be seen.

Determination of ABZSO content in vesicle fluid by HPLC analysis.

Vesicle fluid was isolated from drug-treated and control metacestodes after different times (ranging from 1 h to 16 days) of treatment (Fig. 1). In order to define the ABZSO content in vesicle fluids of drug-treated parasites, we used an HPLC-based method which is routinely used for determination of ABZSO concentrations in plasma of human patients undergoing chemotherapy with albendazole. In samples of vesicle fluid of ABZSN-treated cultures, the presence of ABZSN was assessed qualitatively, starting from 6 h through the entire experiment (16 days), but no exact quantitative determination of drug concentrations was carried out (data not shown).

ABZSO could not be detected in vesicle fluid samples originating either from control metacestodes or from ABZSN-treated metacestodes. However, in cultures treated with ABZSO, the drug was found within the vesicle fluid already after 1 h at a concentration of approximately 2.5 μg/ml, and ABZSO concentrations reached a plateau at around 5.5 μg/ml after 2 h of incubation. During the remaining 16 days, the ABZSO content remained at approximately the same level (Fig. 1). Determination of the ABZSO content in the surrounding medium at selected time points during the experiment showed that the concentration of the drug in the medium remained stable and was therefore always higher than that in the vesicle fluid.

Assessment of the ABZSN content in vesicle fluids originating from ABZSN-treated parasites indicated a similar efficiency of drug uptake, with drug concentrations reaching levels similar to those for ABZSO. In vesicle fluids originating from ABZSO-treated parasites, a peak corresponding to ABZSN was consistently observed, although its intensity was slightly below the detection limit (0.25 μg/ml).

Ultrastructural alterations induced by drug treatment.

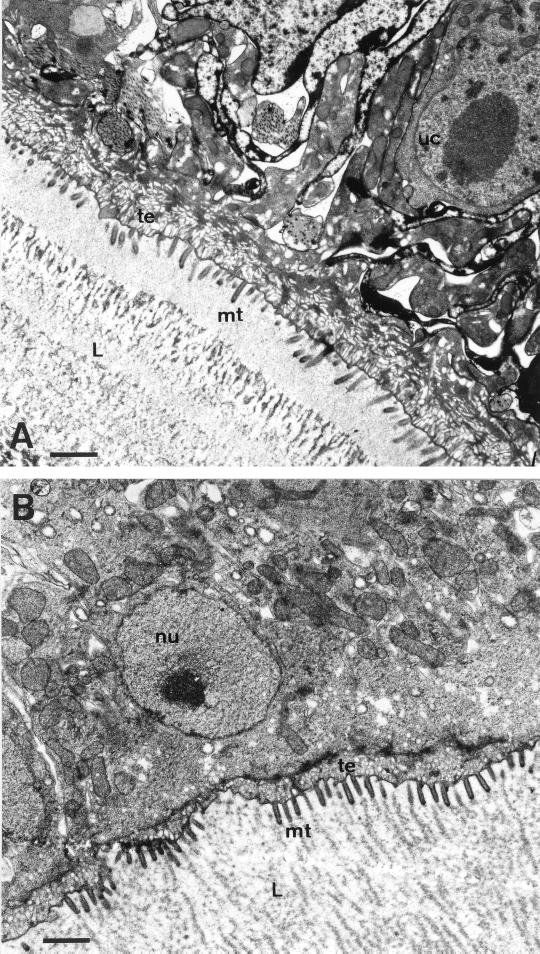

The ultrastructure of vesicle walls of in vitro-cultivated metacestodes has been previously described (17). The external surface of the parasite larvae is comprised of an acellular, heavily glycosylated, laminated layer which surrounds the entire parasite. This laminated layer is followed by the tegument, a syncytial parasite tissue with numerous microtriches protruding well into the laminated layer and thus significantly enhancing the resorbing surface of the parasite. The tegument is followed by the germinal layer, which contains a number of different cell types such as muscle cells, connective tissue, and glycogen storage cells. In actively proliferating vesicles a large number of undifferentiated cells with a large nucleus and nucleolus are found. There were no ultrastructural alterations of parasite tissue observed in control cultures during the entire incubation period of 16 days (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

TEM of E. multilocularis vesicle walls. (A) Untreated parasites (bar, 1.75 μm); (B) parasites after 16 days of cultivation in medium containing a 1:1,000 dilution of DMSO (bar, 1.8 μm). Note that no significant ultrastructural changes can be detected during the cultivation period. L, laminated layer; mt, microtriches; uc, undifferentiated cell; nu, nucleus; te, tegument.

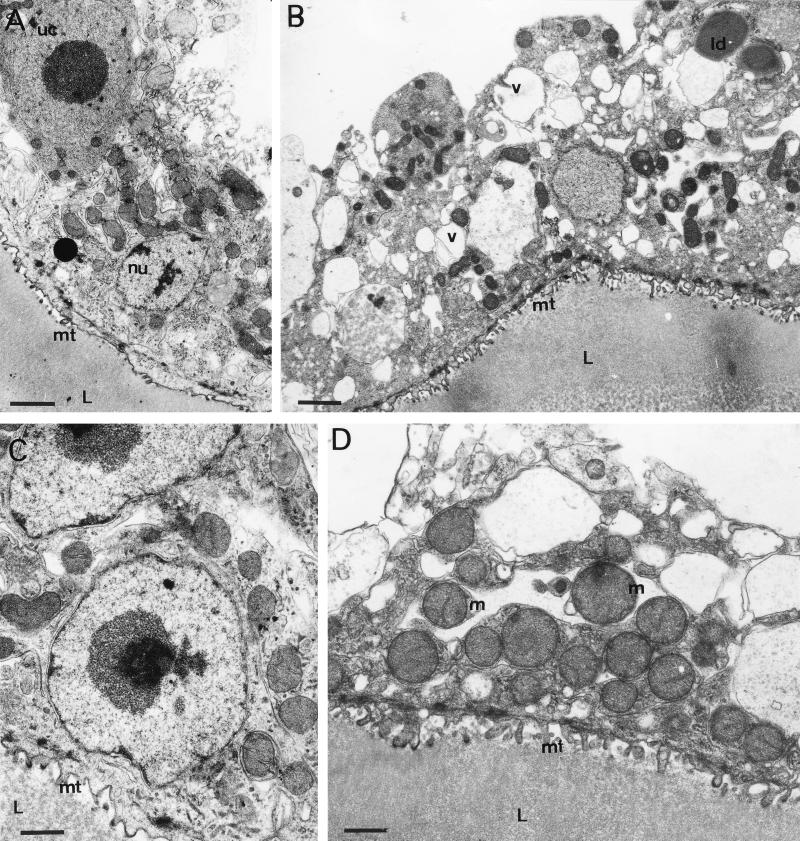

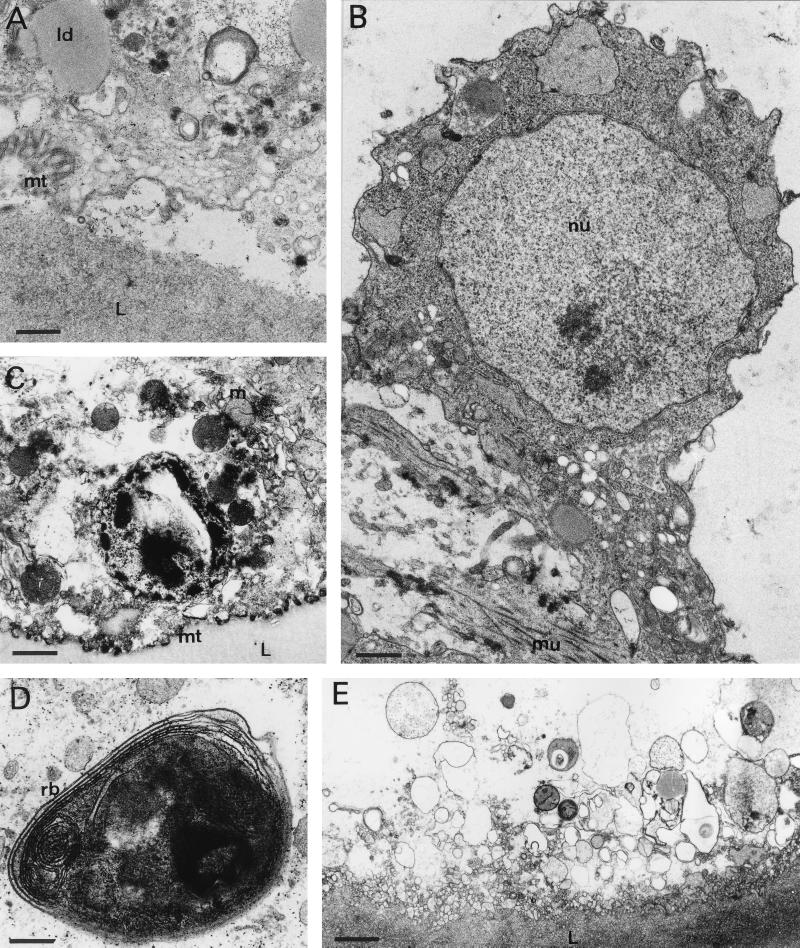

For evaluation of the ultrastructural changes occurring during treatment with ABZSO and ABZSN, it is important to note that the processes of tissue damage progressed at different rates in different cysts, while within a single cyst damage was homogenous. Thus, a larger number of drug-treated vesicles were investigated by TEM in order to obtain a complete picture of the time dependency of tissue alterations induced by these drug treatments. No significant differences between ABZSO- and ABZSN-treated parasites could be detected, while there were marked differences between treated and untreated parasites. The first signs of tissue alterations, characterized by a striking reduction in the number and length of microtriches, could be observed in some vesicles already after 6 h of treatment with either drug (Fig. 3A). Further characteristic changes were observed in samples collected after 24 h of in vitro drug treatment. The distal tegumental and germinal layer tissues became highly vacuolated, and the number of mitochondria within the tegument was increased. Occasionally, lipid droplets could be observed at this early stage, although their number increased dramatically during the later stages of drug treatment (Fig. 3B). Within the first 48 h of drug treatment, tegumental nuclei as well as nuclei from undifferentiated cells remained unaffected and still exhibited a large nucleolus and some chromatin deposits along the nuclear membrane (Fig. 3A and C). Many rounded mitochondria, abnormally increased in size and with altered cristae, could be seen first after 48 h of drug treatment and were more evident after 72 h (Fig. 3D). The processes of degeneration started to become more dramatic at later time points. Five days of treatment with 10 μg of either ABZSO or ABZSN per ml resulted in general desintegration processes which affected large parts of the parasite tissue. Lipid droplets were now visible more often within the treated parasites (Fig. 4A). Microtriches were extensively distorted or even absent in many places, resulting in partial separation from the parasite tissue and laminated layer (Fig. 4A). Undifferentiated cells lost their characteristic nucleolus and started to separate from the rest of the germinal layer-associated tissue (Fig. 4B). After 7 days, the parasite tissue became extensively distorted, microtriches were practically absent (Fig. 4C), and residual bodies containing stacks of electron-dense, lamellated membrane structures were often visible (Fig. 4D). At the latest time point (16 days), only necrotic tissue and residues of the laminated layer were present (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 3.

TEM at early time points (6 to 72 h) during drug treatment. (A) Six hours of treatment with 10 μg of ABZSN per ml (bar, 2 μm): (B) 24 h with 10 μg of ABZSO per ml (bar, 2.3 μm); (C) 48 h with ABZSN (bar, 1.4 μm); (D) 72 h with ABZSO (bar, 1.6 μm). Note the changes in microtriche length and structure, increased vacuolization of the germinal layer, occasional occurrence of lipid droplets, and altered mitochondria. The nuclei of undifferentiated cells and tegumentary cytons still appear normal. mt, microtriche; nu, nucleus; uc, undifferentiated cell; m, mitochondrion; v, vacuole; L, laminated layer; ld, lipid droplet.

FIG. 4.

TEM at later time points (5 to 16 days) during drug treatment. (A) Five days of treatment with ABZSN (bar, 1.3 μm); (B) 5 days with ABZSO (bar, 0.8 μm); (C) 7 days with ABZSO (bar, 1.3 μm); (D) 7 days with ABZSN (bar, 0.8 μm); (E) 16 days with ABZSO (bar, 2.2 μm). Note the generally increasing degeneration of the germinal layer and separation of the parasite tissue from the laminated layer. ld, lipid droplet; m, mitochondrion; mt, microtriches; L, laminated layer; mu, muscle cell; nu, nucleus; rb, residual body.

Analysis of metabolic changes in vesicle fluid and growth medium by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

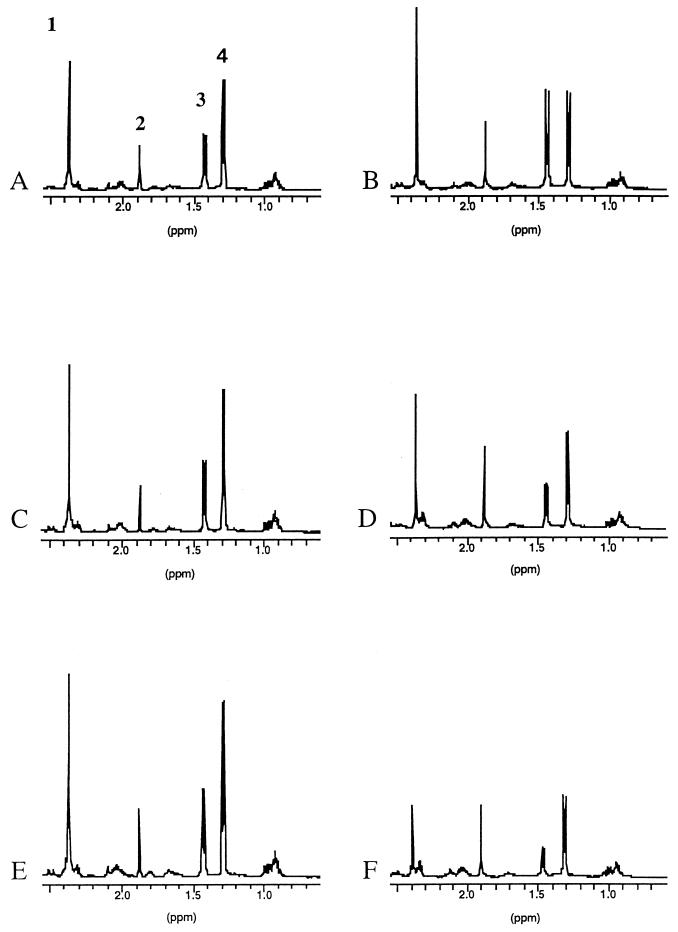

Parasite vesicle fluid and growth medium collected at different time points during drug treatment were analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Typical 1H spectra of vesicle fluid samples at the beginning and at the end of the cultivation period are shown in Fig. 5A and B, respectively. Four main peaks are visible in all control and drug-treated samples (indicated in Fig. 5A). These represent the methylene protons of succinate (peak 1) and the methyl protons of acetate (peak 2), of alanine (peak 3), and of lacate (peak 4). Throughout the cultivation period of 16 days in the absence of any drug, the intensities of the two peaks corresponding to acetate and lactate remained more or less constant, whereas an increase of intensity was observed for succinate and alanine (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

1H NMR spectra of vesicle fluids at time zero (A, C, and E) and after 16 days of cultivation (B, D, and F). The numbers in panel A indicate the identified metabolites succinate (peak 1), acetate (peak 2), alanine (peak 3), and lactate (peak 4). (A and B) Spectra of a control culture incubated in the absence of any drug. Note the relative increase in intensity of the peaks corresponding to succinate and alanine. (C to F) Spectra from cultures incubated in the presence of 10 μg of ABZSO (C and D) or ABZSN (E and F) per ml. Note the changes in the relative peak intensities of acetate and alanine in the drug-treated parasites.

The situation was different for 1H NMR spectra of vesicle fluids originating from ABZSO (Fig. 5C and D)- and ABZSN (Fig. 5E and F)-treated parasites. At the final stage of drug treatment, the intensities of the peaks corresponding to succinate, alanine, and lactate had decreased (most markedly for succinate), whereas the intensity of the acetate peak remained more or less constant. This decrease of signal intensities observed for succinate, alanine, and lactate became evident after 7 days of drug treatment for ABZSO-treated parasites and already after 2 days for ABZSN-treated metacestodes (data not shown). These results indicate that 1H NMR analysis of vesicle fluids can be used to detect alterations in the composition of the main metabolic products in drug-treated E. multilocularis metacestodes compared to untreated parasites.

DISCUSSION

Benzimidazole carbamate derivatives such as mebendazole and albendazole are currently used for the long-term chemotherapy of AE (23). Albendazole is poorly resorbed and is rapidly metabolized to ABZSO and ABZSN, the former of which has been suggested to be the active component (10). Our in vitro drug treatment study has therefore focused on investigating the two albendazole metabolites rather than the effects of albendazole itself.

Clinical experience has shown that chemotherapy alone is not sufficient to effectively cure AE (12, 14), meaning that chemotherapy has a parasitostatic rather than a parasitocidal effect. A Swiss investigation on the long-term course of AE in 70 patients treated with albendazole and mebendazole (1976 to 1989) has shown that 49% of the patients exhibited a regression in larval mass, in 35% of the patients parasite growth could be stabilized, and in 16% treatment was ineffective (27). Similar results were reported from Germany (26). Due to the limited therapeutic success, the development of new means of chemotherapeutically combating AE is warranted. Thus, in vitro models which are suitable for a first-round screening of chemotherapeutically interesting drugs, and which allow a detailed inspection of drug-induced parasite alterations, are needed. In this study, in vitro-cultivated E. multilocularis metacestodes were used to investigate the effects of the metabolic derivatives of albendazole, ABZSO and ABZSN, in vitro. Besides demonstrating morphological and ultrastructural alterations by light and electron microscopy, we also obtained information on the actual drug concentration within the parasite vesicle fluid by using HPLC. We also used 1H NMR spectroscopy of metacestode fluid in order to demonstrate distinct metabolic changes in drug-treated parasites. Such data could provide basic information on metabolic markers useful for in vivo NMR spectroscopy as a noninvasive means of diagnosis of AE-induced lesions and assessment of parasite viability.

The classical criterion to assess vesicle viability in vitro is the loss of metacestode turgidity (9, 16). In this respect, ABZSO and ABZSN had very similar effects. Under the conditions used in this experiment, significant damage to the parasites was first evident morphologically after 5 days of in vitro drug treatment. However, on the ultrastructural level, several tissue alterations could be observed much earlier (Fig. 3). Already after 6 h, microtriches were extensively shortened, distorted, or even absent in many drug-treated metacestodes, suggesting that the parasites reacted against adverse conditions by reducing their resorbing surface. The microtriches are functionally associated with absorption of nutrients from the surrounding medium (39), and their alteration is a first step in a series of events which eventually lead to loss of cyst viability.

The fact that ABZSN also induces extensive ultrastructural alterations and leads to death in of E. multilocularis metacestodes in a way similar to that for ABZSO is somewhat surprising. It was shown previously that in vitro treatment of E. granulosus protoscolices with ABZSN was ineffective and that ABZSN reaches only low levels in serum during chemotherapeutic albendazole treatment, and it has been postulated that ABZSN has no activity towards E. granulosus metacestodes (10, 13, 45).

The ultrastructural alterations induced by ABZSO and ABZSN treatment in our in vitro system (Fig. 3 and 4) were similar to what has been described by Casado et al. (9), who developed an in vitro model for drug screening in E. granulosus cysts. In their system a combination treatment with ABZ and ABZSO was performed. Albendazole, and most likely also its derivatives, inhibits the polymerization of cytoskeletal tubulin (24). This leads to a blockage in cell division and disruption of secretory transport systems. Most effects observed within the first 48 to 72 h in our studies (structural impairment of microtriches, increased vesiculation, and atypical mitochondria) could be attributed to the disruption of intracellular and intercellular transport systems. Finally, both ABZSO and ABZSN treatments lead to ultimate necrosis and parasite death (Fig. 4). A parasitocidal effect of treatment with various concentrations of mebendazole was recently reported by Jura et al. (22). In that study, an in vitro model of E. multilocularis metacestodes with parasites grown in the presence of hepatocytes was used. Ultrastructural investigations were not performed, but the parasitocidal effect of mebendazole treatment was determined by observing the loss of cyst turgidity and by assessments of parasite proliferation.

A parasitocidal effect has normally not been observed during benzimidazole chemotherapy in human AE patients. In addition, extensive drug treatment trials in laboratory animals suggested that continuous long-term administration of albendazole can arrest E. multilocularis metacestode growth and metastases in a large portion of cases but that the parasite itself is not killed. For instance, infected cotton rats were used to assess the ultrastructural effects of in vivo albendazole and praziquantel therapy (33). The germinal layer of albendazole-treated cysts in these cotton rats differed little from control tissue, with the exception of a marginal increase in cyton vesiculation and the presence of small lamellated residual bodies. Although treatment increased the survival time of these animals and reduced the parasite weight, viable infection always remained present after treatment (33). Similar results were obtained during studies of the effects of albendazole treatment on E. multilocularis infection in gerbils (37). Further studies with gerbils showed that this drug was more effective than mebendazole in reducing cyst growth (41). Using a murine model, Rodriguez et al. (35) described a novel injectable formulation of albendazole and the evaluation of its efficacy against E. multilocularis metacestodes. They applied a colloidal delivery system comprised of poly-l-lactide nanoparticles loaded with albendazole. Both the size of the aggregation of tissue of the metacestode in the liver and the peritoneal metastatic burden were significantly reduced by this treatment compared to those in untreated mice. However, compared to mice treated by oral administration of the drug, there was no significant difference (35). Another study with cotton rats indicated that the efficacy of oral albendazole administration could be increased if the drug is entrapped in liposomes and coadministered with cimetidine (43). There appeared to be a synergistic effect between albendazole and cimetidine, since the metabolism of albendazole was markedly altered and a greater therapeutic effect was observed. A more recent study provided evidence that the effect of albendazole in gerbils infected with E. multilocularis metacestodes can also be increased by administring the drug in combination with the dipeptide methyl ester Phe-Phe-OMe (36). Although all of these in vivo studies investigated either the ultrastructural characteristics of drug-treated parasites or the effects on parasite growth, they did not obtain information on drug uptake by the parasite or assess the metabolic changes occurring within the parasite.

By using HPLC analysis of vesicle fluids collected after various times of in vitro drug treatment, it was found that the drug had reached the interior of the parasite within a very short time (Fig. 1). This confirmed results previously obtained with E. granulosus cysts (13, 28), which showed that ABZSO penetrates the cyst membrane through simple diffusion. In E. granulosus cysts, the concentration of the drug in the vesicle fluid was always between 13 and 22% of the concentration in serum (28). Our in vitro studies on E. multilocularis metacestodes indicate also that the concentration of the drug within the vesicle fluids never reaches the concentration in the surrounding medium. The mechanisms which lead to this discrepancy are not known. The same is true for ABZSN, although in our study this drug was not assessed quantitatively. However, it has been shown recently that ABZSN exhibited an even higher degree of penetration into E. granulosus cyst membranes than ABZSO (13).

Although TEM has been widely used to assess the effects of in vivo drug treatment of AE and hydatid disease in laboratory animals, ultrastructural investigations have inherent limitations and should therefore be treated with caution. There is a considerable amount of variation in the germinal layers of both E. multilocularis and E. granulosus (11, 32) in vivo and also in vitro, and natural tissue degeneration occurs in E. multilocularis (33, 34). Thus, we tested whether changes in the parasite metabolite composition in the vesicle fluid could be used as an additional criterion to differentiate between healthy and drug-treated parasites. We defined changes in parasite metabolites by analyzing vesicle fluids of control and drug-treated parasites by 1H NMR spectroscopy. In parasitology, 31P NMR has been used to monitor levels of phosphorous-containing molecules important in energy metabolism (PCr, ATP, ADP, and glucose-6-phosphate), while 13C NMR has been used to provide details about metabolic pathways such as carbohydrate metabolism (5, 7). There have been relatively few 1H NMR studies on parasites, probably due to the complexity of the proton NMR spectra, despite the higher degree of sensitivity (6). However, Novak et al. (29) had previously analyzed cyst extracts of E. multilocularis metacestodes grown subcutaneously and in the peritoneal cavity of M. unguiculatus by using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Our studies confirm their earlier results that the main metabolites present in vesicle fluid are succinate, acetate, alanine, and lactate. These compounds are all end products of the accepted pathways of glucose metabolism in tapeworms (4, 40). The fact that drug treatment caused a different alteration in their concentrations indicates that the energy metabolism in drug-treated parasites was significantly influenced by treatment with both ABZSO and ABZSN. This is not surprising, since benzimidazoles also induce the blockage of glucose absorption and lead to glycogen depletion (42).

The detection of altered metabolites by 1H NMR could now provide a basis for improving assessments of E. multilocularis cyst viability in human patients by means of a noninvasive technique. To date, determination of parasite viability has involved surgery and subsequent inoculation of biopsy material into laboratory animals. However, the experimental mouse inoculation technique requires several months before parasite viability can be determined and represents a considerable psychological as well as physical constraint to the patient. In addition, removal of parasite tissue could result in metastasis. Although AE is not regarded as one of the major parasitic diseases, the consequences for the individual patient are extremely grave, and the disease leads to death in those patients for whom chemotherapy is unsuccessful in halting parasite growth (23). New means of chemotherapeutic treatments and assessment of prognostic parameters are required. The in vitro cultivation model for E. multilocularis metacestodes presented here provides an ideal first-round test system for screening of antiparasitic drugs. This would reduce the amount of animal experimentation, which involves elevated costs and requires long periods to obtain conclusive results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The drugs used in this study were kindly provided by John Horten, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, London, United Kingdom. Many thanks are addressed to Norbert Müller and Richard Felleisen (Institute of Parasitology, University of Bern) for critical comments on the manuscript. We also thank Maja Suter and Toni Wyler (Institute of Veterinary Pathology and Institute of Zoology [University of Bern], respectively) for access to their electron microscopy facilities. Christian Müller and Peter Strähl (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry), as well as Regula Theurillat and Malica Chouki (Department of Clinical Pharmacology) are gratefully acknowledged for their excellent technical assistance.

This study was financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 3100-045575.95) and by the Stiftung zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung der Universität Bern.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammann R W, Hirsbrunner R, Cotting J, Steiger U, Jacquier P, Eckert J. Recurrence rate after discontinuation of long-term mebendazole therapy in alveolar echinococcosis (preliminary results) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:506–515. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammann R W, Ilitsch N, Marincek B, Freiburghaus A U. Effect of chemotherapy on the larval mass and the long-term course of alveolar echinococcosis. Hepatology. 1994;19:735–742. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammann R W Swiss Echinococcosis Study Group. Improvement of liver resectional therapy by adjuvant chemotherapy in alveolar hydatid disease. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:290–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00930903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barret J. Biochemical pathways in parasites. In: Rogan M, editor. Analytical parasitology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1997. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behm C A, Bryant C, Jones A J. Studies on glucose metabolism in Hymenolepis diminuta using 13C nuclear magnetic resonance. Int J Parasitol. 1987;17:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(87)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackburn B J, Hudspeth C, Novak M. 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance study of three species of Hymenolepis adults. Parasitol Res. 1993;79:334–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00932191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn J, Hutton H M, Novak M, Evans W S. Hymenolepis diminuta: nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of the secretory products resulting from the metabolism of 13C6 glucose. Exp Parasitol. 1986;62:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(86)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casado N, Perez-Serrano J, Denegri G, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Development of truncated microtriches in Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:355–357. doi: 10.1007/BF02351880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casado N, Perrez-Serrano J, Denegri G, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Development of a chemotherapeutic model for the in vitro screening of drugs against Echinococcus granulosus cysts: the effects of an albendazole-albendazolesulphoxide combination. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(95)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinnery J B, Morris D L. Effect of albendazolesulphoxide on viability of hydatid protoscoleces in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:815–817. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delabre I, Gabrion C, Contant F, Petavy A-F, Deblock S. The susceptibility of the mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) and the OFa mouse strain to Echinococcus multilocularis—ultrastructural aspects of the cysts. Int J Parasitol. 1987;17:773–780. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(87)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert J. Prospects for treatment of the metacestode stage of Echinococcus. In: Thompson R C A, editor. The biology of Echinococcus and hydatid disease. London, United Kingdom: Allen & Unwin; 1986. pp. 250–284. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Llamazares J L, Alvarez-de-Felipe A I, Redondo-Cardena P A, Prieto-Fernandez J G. Echinococcus granulosus: membrane permeability of secondary hydatid cysts to albendazolesulfoxide. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:417–420. doi: 10.1007/s004360050420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil-Grande L A, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F, Prieto J G, Sanchez-Ruano J J, Brasa C, Aguilar L, Garcia-Hoz F, Casada N, Barcena R, Alvarez A I. Randomized controlled trial of efficacy of albendazole in intra-abdominal hydatid disease. Lancet. 1993;342:1269–1272. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92361-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottstein B. Echinococcus multilocularis infection: immunology and immunodiagnosis. Adv Parasitol. 1992;31:321–379. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heath D D, Christie M J, Chevis R A F. The lethal effect of mebendazole on secondary Echinococcus granulosus cysticerci and Taenia pisiformis and tetrahydria of Mesocestoides corti. Parasitology. 1975;70:273–285. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000049738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemphill A, Gottstein B. Immunological and morphological studies on the proliferation of in vitro cultivated Echinococcus multilocularis metacestode. Parasitol Res. 1995;81:605–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00932028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemphill A, Gottstein B. In vitro cultivation and proliferation of Echinococcus multilocularis metacestode. In: Urchino J, Sato N, editors. Alveolar echinococcosis, strategy for eradication of alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. Sapporo, Japan: Fuji Shoin; 1996. pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemphill A, Croft S L. Electron microscopy in parasitology. In: Rogan M, editor. Analytical parasitology. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1997. pp. 227–268. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horten R J. Chemotherapy of Echinococcus infection in man with albendazole. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingold K, Gottstein B, Hemphill A. Identification of a novel laminated layer-associated protein in Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes. Parasitology. 1998;116:363–372. doi: 10.1017/s0031182098002406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jura H, Bader A, Frosch M. In vitro activities against Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1052–1056. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kern P, Wechsler J G, Lauchart W, Kunz R. Klinik und Therapie der alveolären Echinokokkose. Deutsches Aerzteblatt-Aerztliche Mitteilungen. 1994;91:B1857–B1863. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacey E. Mode of action of benzimidazoles. Parasitol Today. 1990;6:112–115. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90227-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton P, Hemphill A, Deplazes P, Gottstein B, Sarciron M E. Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes: immunological and immunocytochemical analysis of the relationships between alkaline phosphatase and the Em2 antigen. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:142–149. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löscher T, von Sonnenburg F, Nothdurft H D. Epidemiology and therapy of human echinococcosis in central Europe. 8th International Congress for Tropical Medicine and Malaria. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesarini-Wicki B. Long-term course of alveolar echinococcosis in 70 patients treated by benzimidazol derivates (mebendazole and albendazole) (1976–1989). Inaugural dissertation. Zürich, Switzerland: Universitätsspital Zürich; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris D L, Chinnery J B, Georgiou G, Stamatakis G, Golematis B. Penetration of albendazolesulphoxide into hydatid cysts. Gut. 1987;28:75–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak M, Hameed N, Buist R, Backburn B J. Metabolites of alveolar Echinococcus as determined by 31P- and 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Parasitol Res. 1992;78:665. doi: 10.1007/BF00931518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Serrano J, Denegri G, Casado N, Bodega G, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Anti-tubulin immunohistochemistry study of Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices incubated with albendazole and albendazolesulphoxide in vitro. Parasitol Res. 1995;81:438–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00931507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rausch R L, Wilson J F, Schantz P M, McMahon B J. Spontaneous death of Echinococcus multilocularis: cases diagnosed by Em2 ELISA and clinical significance. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;36:576–585. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards K S, Arme C, Bridges J F. Echinococcus granulosus equinus: variation in the germinal layer of murine hydatids and evidence of autophagy. Parasitology. 1984;89:35–37. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richards K S, Morris D L, Taylor D H. Echinococcus multilocularis: ultrastructural effect of in vivo albendazole and praziquantel therapy, singly and in combination. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;83:479–484. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1989.11812375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richards K S, Morris D L. Effect of albendazole on human hydatid cysts: an ultrastructural study. HPB Surg. 1990;2:105–112. doi: 10.1155/1990/47243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez J M, Bories C, Emery I, Fessi H, Devissaguet J P, Liance M. Development of an injectable formulation of albendazole and in vivo evaluation of its efficacy against Echinococcus multilocularis metacestode. Int J Parasitol. 1995;12:1437–1441. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(95)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarciron M E, Walchshofer N, Walbaum S, Arsac C, Descotes J, Petavy A-F, Paris J. Increases in the effects of albendazole on Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes by the dipeptide methyl ester (Phe-Phe-OMe) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:226–230. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schantz P M, Brandt F H, Dickinson C M, Allen C R, Robert J M, Eberhard M L. Effects of albendazole on Echinococcus multilocularis infection in the Mongolian jird. J Infect Dis. 1996;162:1403–1407. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siles-Lucas, M., R. Felleisen, A. Hemphill, W. Wilson, and B. Gottstein. Stage-specific expression of Echinococcus multilocularis protein 14-3-3. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 91:281–293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Smyth J D, Howkins A B, Barton M. Factors controlling the differentiation of the hydatid organism, Echinococcus granulosus, into cystic or strobilar stages in vitro. Nature. 1966;211:1374–1377. doi: 10.1038/2111374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smyth J D, McManus D P. The physiology and biochemistry of cestodes. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor D H, Morris D L, Reffin D, Richards K S. Comparison of albendazole, mebendazole and praziquantel chemotherapy of Echinococcus multilocularis in a gerbil model. Gut. 1989;30:1401–1405. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.10.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van den Bossche H. Mode of action of anticestodal agents. In: Campbell W C, Rew R S, editors. Chemotherapy of parasitic diseases. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wen H, New R R, Muhmut M, Wang J H, Wang Y H, Zhang J H, Shao Y M, Craig P S. Pharmacology and efficacy of liposome-entrapped albendazole in experimental secondary alveolar echinococcosis and effect of co-administration with cimetidine. Parasitology. 1996;113:111–121. doi: 10.1017/s003118200006635x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson J F, Rausch R L, McMahon B J, Schantz P M. Parasitocidal effect of chemotherapy in alveolar hydatid disease: a review of experience with mebendazole and albendazole in Alaskan Eskimos. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:234–249. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeugin T, Zysset T, Cotting J. Therapeutic monitoring of albendazole: a high performance liquide chromatography method for determination of its active metabolite albendazole sulfoxide. Ther Drug Monit. 1990;12:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]