Abstract

Molecular analysis of 17 genomically unrelated clinical VanB-type vancomycin-resistant enterococcus isolates from hospital patients in Germany, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States revealed three subtypes of the vanB gene cluster—vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3—which was in accordance with previous subtyping of the ligase gene sequence. There was no correlation between vanB subtype and levels of vancomycin resistance. All strains studied carried a structurally conserved vanB gene cluster as shown by long-range PCR (long PCR) covering 5,959 bp of the published sequence in vanB1 strain V583. Restriction analysis of long PCR amplicons displayed one unique vanB1 pattern and a second vanB2- and vanB3-specific pattern. The vanSB-vanYB intergenic sequences with flanking coding regions were identical within each vanB subtype with one exception. A U.S. vanB2 isolate had a 789-bp enlargement of this region containing a putative open reading frame (ORF) with substantial homology to an ORF in the Clostridium perfringens IS1469 insertion element. The molecular heterogeneity within the vanB gene cluster has implications for the selection of PCR primers, as the primers must ensure detection of all vanB subtypes, and is of importance when considering reservoirs and dissemination of vanB resistance. The molecular identity within the vanB1 and the vanB2 subtype indicates horizontal transmission of both gene clusters between isolates in different geographical areas. Restriction analysis of long PCR vanB amplicons may reveal specific varieties that can be used as epidemiological markers for mobile determinants conferring VanB-type resistance. The finding of three distinct vanB gene clusters should encourage a search for different environmental reservoirs of vanB resistance determinants.

Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci is phenotypically and genotypically heterogeneous. The VanA and the VanB types are the most commonly encountered forms of acquired glycopeptide resistance (1, 24) and have the same basic mechanism of resistance (8). VanA-type strains show inducible resistance to high levels of vancomycin and moderate to high levels of teicoplanin. The vanA gene cluster is located on transposon Tn1546 or related elements and can be part of the chromosome, on nonconjugative or conjugative plasmids (14, 15). The VanB phenotype, mediated by the vanB gene cluster (see Fig. 3) (8–10), is characterized by inducible resistance to various levels of vancomycin and susceptibility to teicoplanin (25). The vanB gene cluster can reside on a composite transposon, Tn1547, but is not always linked to IS16- or IS256-like elements, which characterize Tn1547 (24). A novel chromosomal vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) was recently described in clonally distinct U.S. Enterococcus faecium strains (5, 16). Dissemination of VanB-type resistance among enterococci results from conjugation of plasmids (2, 30) or large chromosomal elements ranging from 90 to 250 kb in size (5, 23).

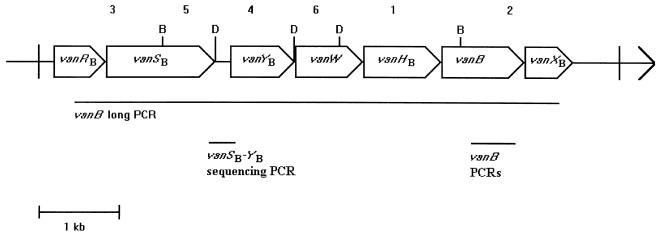

FIG. 3.

Restriction pattern and PCR products in the vanB gene cluster. Restriction pattern and PCR products are deduced from the sequence of the reference strain V583. D, DraI; B, BspHI; 1 to 6, BspHI/DraI restriction fragments with decreasing sizes as follows: 1,491, 1,202, 1,086, 960, 654, and 566 bp, respectively. Open arrows represent coding sequences as labeled.

Recent reports (12, 22) have shown DNA sequence heterogeneity suggesting three subtypes of the vanB ligase gene: vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3. The vanB1 gene has previously been designated vanB (6, 10, 12, 22). However, to our knowledge potential differences in the organization and structure of the vanB gene clusters in genomically diverse vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) strains have not been examined extensively.

Possible mechanisms for the spread of vanB-possessing VRE include both horizontal transfer of the vancomycin resistance genes as well as clonal dissemination of strains. Epidemiological studies of VRE should therefore apply total bacterial DNA analysis as well as molecular characterization of mobile resistance determinants. We have developed a long-range PCR (long PCR) for the structural analysis of vanB gene clusters in VRE, Tn1547 PCR (13). The designation Tn1547 PCR may, however, not be very accurate, as this PCR covers the vanB gene cluster and cannot be used to determine if the cluster is located on the Tn1547 transposon or other mobile DNA elements (5). In the present work we have renamed this PCR vanB long PCR. The objective of the present study was to characterize the vanB gene cluster of genomically unrelated VRE isolates from European countries and the United States. The strains were examined by restriction fragment length pattern (RFLP) analysis of long PCR amplicons and DNA sequencing of the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region as well as part of the vanB gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The VanB strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis ATCC 29212, E. faecium ATCC 19434, E. gallinarum ATCC 49608, E. casseliflavus ATCC 25788, and E. faecalis V583 CDC (26) were used as control strains during bacterial identification, PCRs, and DNA sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Strain information and structural data on vanB gene clustersa

| Strain reference no. | Origin | Designation used by other laboratory(ies) | Species | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

vanB PCR sequence | vanB long PCR-RFLP profile | vanSB-vanYB sequence | PFGE pattern | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | Teicoplanin | ||||||||

| TUH1-3b | United States | V583 CDC | E. faecalis | 96 | 0.19 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | I |

| TUH1-75 | Sweden | B8 | E. faecalis | 24 | 0.094 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | II |

| TUH1-79 | Norway | 112681 | E. faecium | 12 | 0.064 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | III |

| TUH2-18 | Norway | 25942/96 | E. faecium | 12 | 0.19 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | IV |

| TUH4-54 | United Kingdom | B2 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.38 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | V |

| TUH4-64 | United States | E45-7 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.50 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | VI |

| TUH4-65 | United States | E57-1 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.19 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | VII |

| TUH4-66 | United States | E76-3 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 1.0 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | VIII |

| TUH4-67 | United States | E83-10 | E. faecalis | ≥256 | 0.25 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | IX |

| TUH4-68 | United States | E11-10 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.064 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | X |

| TUH7-13 | United States | 123-7540-1 | E. faecalis | 32 | 0.125 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | XI |

| TUH7-14 | United States | 116-1021-1 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.75 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | XII |

| TUH7-15 | United States | 110-1309-1 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.19 | vanB2 | RFLP-2*c | vanB2*c | XIII |

| TUH7-16 | Norway | RH#57II | E. gallinarum | 32 | 0.25 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | XIV |

| TUH7-53 | Germany | UW 1487 | E. faecalis | ≥256 | 0.19 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 | vanB1 | XV |

| TUH7-54 | Germany | UW 683 | E. faecalis | ≥256 | 0.50 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | XVI |

| TUH7-55 | Germany | UW 1551 | E. faecium | ≥256 | 0.38 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 | vanB2 | XVII |

| TUH7-68 | United States | VRE 45 | E. faecalis | ≥256 | 0.25 | vanB3 | RFLP-2 | vanB3 | XVIII |

These strains were considered clinically relevant, except for TUH7-16, which is a colonization strain, and TUH4-54, whose clinical relevance is unknown.

V583 CDC (26) was used as a reference strain for PCR, RFLP analysis, and sequence alignment. This strain also had a PFGE pattern distinct from those of the other vanB strains in this collection.

RFLP fragment 4 in isolate TUH7-15 was 789 bp larger than that in the RFLP-2 due to an insertion in the vanSB-vanYB region.

Bacterial identification and susceptibility testing.

The isolates were identified by positive Gram stain, absence of catalase, and presence of pyrrolidonylarylamidase activity as shown by the DrySlide PYR test (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). The strains were phenotypically identified to the species level by the ATB Rapid ID 32 STREP test (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), motility in modified Difco motility medium, and pigmentation after overnight growth on tryptic soy agar (11). Some of the strains were in addition identified by a slightly modified species-specific ddl PCR (7). MICs for vancomycin and teicoplanin were determined by E test on PDM agar (PDM antibiotic sensitivity medium II; AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) with a final inoculum of about 5 × 105 CFU/ml.

PFGE typing.

VanB-type VRE isolates from hospital patients in Norway (n = 3), Sweden (n = 1), the United Kingdom (n = 1), Germany (n = 3), and different locations in the United States (n = 9) were typed by SmaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) digestion and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of chromosomal DNA as described by Murray et al. (21) with some modifications. Briefly, RNase One (0.5 U/ml; Promega, Madison, Wis.), lysozyme (1 mg/ml), proteinase K (4 mg/ml; Promega), SmaI (20 U/ml), a final agarose concentration of 0.8% in the agarose plugs, and a CHEF-DR III device (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) were used. The pulse time was increased from 1 to 35 s over 29 h at 200 V.

PCR.

Preparation of bacterial DNAs was performed by using a Dynabeads DNA DIRECT kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as described by Haaheim et al. (13). PCRs were performed in a GeneAmp PCR system (model 2400; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Primer sequences and target regions used for amplification in this study are listed in Table 2. The vanB gene was amplified by the use of vanB1-specific (previously designated vanB) primers (6) as well as a vanB consensus PCR designed in our laboratory to amplify all vanB subtypes. PCR conditions were as previously described (6). The vanB gene-positive strains were further analyzed by a vanB long PCR (13) that covers 5,959 bp of the published vanB gene cluster from strain V583 (8) and by sequencing of the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region as well as partial vanB gene sequencing. E. faecium ATCC 19434 was used as a negative control and E. faecalis V583 CDC was used as a positive control in the vanB, vanB long, and vanSB-vanYB PCRs. The vanSB-vanYB PCR was carried out with the Perkin-Elmer standard PCR reaction mix with GeneAmp PCR buffer. Amplification conditions were 94°C initially for 1 min; 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min over 25 cycles; and a final 5-min extension period at 72°C.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used to characterize the vanB gene cluster in VRE strains used in this study

| PCR | Product size (bp) | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Locationa |

|---|---|---|---|

| vanB1b | 433 | GTG ACA AAC CGG AGG CGA GGA | 5,434–5,454 |

| CCG CCA TCC TCC TGC AAA AAA | 5,866–5,846 | ||

| vanB consensusc | 484 | CAA AGC TCC GCA GCT TGC ATG | 5,340–5,360 |

| TGC ATC CAA GCA CCC GAT ATA C | 5,823–5,802 | ||

| vanSB-vanYB | 309 | ATA TGC GCT GGA AAA CAC CTC | 2,114–2,134 |

| CCC CAG ATT GTT TCA TAT GCC | 2,422–2,402 | ||

| vanB longd | 5,959 | GTT TGA TGC AGA GGC AGA CGA CT | 450–472 |

| ACA AGT TCC CCT GTA TCC AAG TGG | 6,408–6,385 |

The nucleotide positions given are according to the published sequence of the V583 vanB gene cluster (8).

These primers are described by Clark et al. for a PCR designated vanB (6) which amplifies the vanB1 gene.

This vanB PCR amplifies all known subtypes of the vanB gene.

These primers are described by Haaheim et al. (13).

RFLP analysis and DNA sequencing.

BspHI/DraI (New England Biolabs)-digested vanB long PCR products were analyzed on ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. Both strands of the 484-bp vanB consensus primer amplicons and the 309-bp vanSB-vanYB amplicons were directly sequenced by using ABI Prism 377 (Perkin-Elmer) with the primers listed for these PCRs (Table 2) and dye-labeled terminators (Perkin-Elmer). The sequencing PCRs included cycles of 96°C for 1 min followed by 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 4 min over 25 cycles.

RESULTS

The results are summarized in Table 1. The 17 human VRE isolates were identified as 10 E. faecium strains, 6 E. faecalis strains, and 1 E. gallinarum strain. All isolates were shown to belong to different genome types by SmaI digestion and PFGE according to the criteria described by Tenover et al. (27).

The results from the vanB1-specific and vanB consensus PCRs indicated the presence of 7 vanB1 isolates and 10 vanB2 or vanB3 isolates in this strain collection. The 484-bp vanB consensus primer amplicons were sequenced in order to confirm this assumption and to examine sequence heterogeneity within each subtype. The seven vanB1 strains showed sequence identity compared to the reference strain V583 (8) in the 406-bp readable sequence region. Nine isolates revealed a vanB2-specific sequence according to Gold et al. (12). In comparison to the original vanB2 gene sequence (12), one single point mutation was detected in TUH7-54 (position 5,499, T→G) and TUH7-15 (position 5,423, G→T). Two point mutations were detected in TUH4-54 (position 5,385, A→G; position 5,490, T→G) (data not shown). Strain TUH7-68, the original vanB3 strain (22), was the only vanB3 isolate studied.

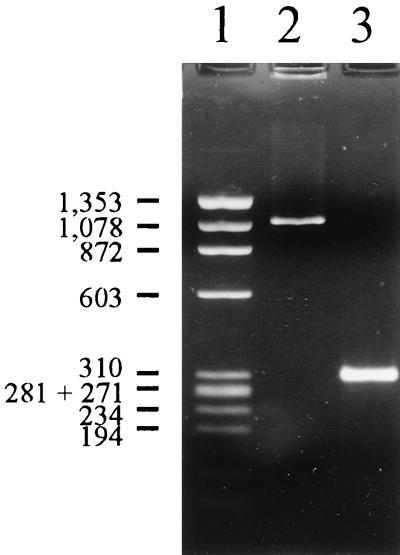

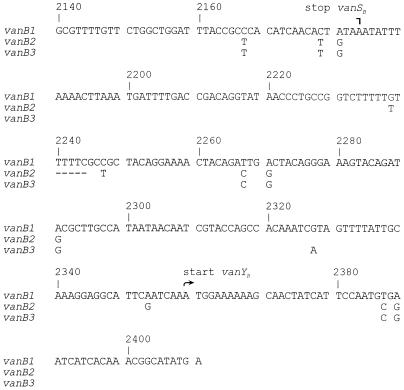

A 309-bp amplicon (Fig. 1, lane 3) spanning the 175-bp vanSB-vanYB intergenic region and flanking coding sequences was bidirectionally sequenced in order to examine vanB intergenic sequence subtype specificity in a noncoding sequence. The 271-bp readable sequence corresponded to nucleotide positions 2,140 to 2,410 in the V583 vanB1 gene cluster (Fig. 2). The sequence of the vanB1 isolates was identical to the published sequence of strain V583 (GenBank accession no. U35369) with eight unique base pairs compared to the corresponding vanB2 and vanB3 intergenic regions. Eleven identical single point mutations and a 5-bp deletion were detected in the vanB2 strains in comparison to the vanB1 sequence (GenBank accession no. AF125544-AF125548 and AF125550 to AF125552). The vanB3 isolate (GenBank accession no. AF125553) had eight single point mutations common to the vanB2 subtype and only one unique base pair in the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

PCR amplification of the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region. Shown is a representative agarose electrophoresis gel of the vanSB-vanYB PCR products. Lane 1, φX174 DNA HaeIII digest (Promega); lane 2, isolate TUH7-15 amplicon of 1,098 bp; lane 3, typical 309-bp amplicon, represented by isolate TUH4-64. Molecular sizes shown to the left of the gel (in base pairs) refer to the φX174 DNA HaeIII digest.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of DNA sequences of vanSB-vanYB amplicons. Shown is a comparison of vanSB-vanYB DNA sequences, represented by vanB1 isolate TUH4-64 (identical to the vanSB-vanYB region of the V583 vanB gene cluster), vanB2 isolate TUH2-18, and vanB3 isolate TUH7-68. Base pair differences between the vanB1 and the vanB2 and vanB3 strains are shown by single letters below the vanB1 cluster sequence. Gaps are shown by dashes. Nucleotide positions and stop vanSB and start vanYB positions, according to the published vanB gene cluster sequence of reference strain V583, are shown above the aligned sequences.

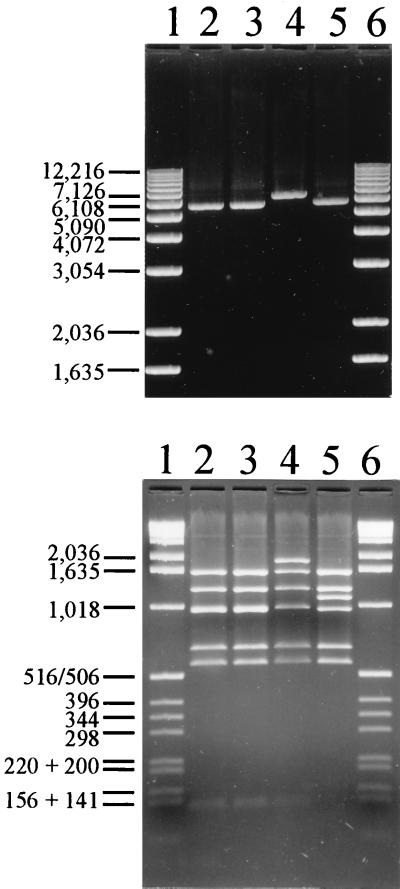

The vanB long PCR, covering 5,959 bp of the published 6,436-bp vanB gene cluster (Fig. 3), was positive in all isolates. RFLP analysis of the vanB long PCR products revealed identical patterns within the vanB1 and the vanB2 gene clusters, RFLP-1 and RFLP-2, respectively. RFLP-1 was in accordance with the vanB gene cluster sequence of the vanB1 reference strain V583. The vanB2 strain TUH7-15 showed a unique RFLP-2 profile, RFLP-2* (see below), while the vanB3 strain TUH7-68 displayed an RFLP-2 profile. Restriction analyses of the vanB long PCR amplicon from the vanB2 strain TUH2-18 by using BspHI and DraI separately (data not shown) showed that RFLP-2 was the result of an additional BspHI site in the 1,086-bp fragment 3 (Fig. 3) covering position 450 to 1,535 in the V583 sequence. This BspHI site results in two bands of approximately 130 and 960 bp in the vanB2 and vanB3 isolates compared to the 1,086-bp fragment in the vanB1 strains (Fig. 4, bottom). The additional 960-bp fragment in vanB2 and vanB3 strains is not visible in Fig. 4 (bottom) because this fragment runs superimposed on fragment 4 in the gel. However, both fragments can be visualized by restriction analyses with BspHI and DraI separately (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of vanB long PCR amplicons. (Top) Representative agarose electrophoresis gel of vanB long PCR amplicons. Lanes 1 and 6, 1-kb ladder (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.); lane 2, vanB2 isolate TUH2-18; lane 3, vanB3 isolate TUH7-68; lane 4, vanB2 isolate TUH7-15 with a 789-bp insertion; lane 5, vanB1 isolate TUH4-64. (Bottom) Restriction fragment analysis of vanB long PCR amplicons. Shown are BspHI/DraI-digested vanB long PCR amplicons analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Lanes 1 and 6, 1-kb ladder; lane 2, vanB2 isolate TUH2-18 with RFLP-2; lane 3, vanB3 isolate TUH7-68 RFLP-2; lane 4, vanB2 isolate TUH7-15 with a 789-bp enlargement of fragment 4 (RFLP-2*); lane 5, vanB1 isolate TUH4-64 with RFLP-1. Molecular sizes shown to the left of each gel (in base pairs) refer to the 1-kb ladder.

The vanB long PCR amplicon from one U.S. isolate (TUH7-15) was larger than expected (Fig. 4, top, lane 4). This vanB2-type amplicon had an ∼800-bp enlargement of fragment 4 (RFLP-2*) covering the vanSB-vanYB region of the gene cluster (Fig. 4, bottom). The enlargement of the vanSB-vanYB region was confirmed by vanSB-vanYB-specific PCR (Fig. 1, lane 2) and sequencing (data not shown). This vanB2 isolate had a 789-bp insertion in a vanB2-type vanSB-vanYB intergenic region containing a putative open reading frame. The first 147 amino acids showed 70% homology to the first 147 amino acids of an open reading frame in the Clostridium perfringens IS1469 insertion element (3, 4) by comparison with known sequences performed by using the BLAST program.

Six of nine U.S. strains possessed the vanB1 gene, whereas 7 of 8 European strains possessed the vanB2 gene. The different strains showed various MICs of vancomycin, ranging from 32 to ≥256 μg/ml within the vanB1 group and from 12 to ≥256 μg/ml within the vanB2 group. MICs of teicoplanin were ≤1 μg/ml for all strains.

DISCUSSION

The presented molecular analysis of 17 genomically unrelated clinical VanB-type VRE from Europe and the United States reveals that vanB gene clusters could be divided in three distinct subtypes: vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3. There was no correlation between vanB subtype and level of vancomycin resistance. The vanB1 and vanB2 gene clusters were demonstrated in both European and U.S. strains, while the vanB3 gene cluster was detected in only one U.S. strain. The organization of the vanB gene clusters, as shown by RFLP analysis of long PCR amplicons, is highly conserved within the vanB1 and vanB2 subtypes. All PCR-confirmed vanB1 gene isolates showed an RFLP-1 profile and identical vanB1-subtype vanSB-vanYB intergenic sequences. Eight of the nine sequence-confirmed vanB2 isolates showed an RFLP-2 profile and a conserved vanB2-subtype vanSB-vanYB intergenic sequence. The vanB3 strain revealed a vanB long PCR RFLP-2 profile and an intergenic vanSB-vanYB sequence with partial identity to both vanB1 and vanB2 sequences. One unique RFLP-2* profile was detected in the vanB2 strain TUH7-15 due to an insertion of 789 bp in the vanSB-vanYB area. Further characterization of this insertion element is in progress.

Our observations are consistent with earlier descriptions of vanB gene sequence heterogeneity (12, 22). Gold and coworkers (12) proposed the vanB2 genotype based on a 3.6% base pair difference from the vanB1 ligase gene sequence of strain V583. Patel et al. (22) demonstrated sequence heterogeneity within the vanB2 gene and designated two clinical vanB VRE isolates with identical PFGE patterns to a vanB3 genotype. The 801 bp of the vanB3 gene (22) had a 3.6% base pair difference from the published vanB2 gene sequence (12) and a 5% base pair difference from the V583 vanB1 gene (8). The vanB consensus primers designed in our laboratory are able to direct amplification of vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 genes under stringent PCR conditions. The vanB1-specific primers described by Clark and coworkers (6) did not direct amplification of vanB2 and vanB3 genes. They could therefore be used to distinguish the vanB1 gene from vanB2 and vanB3 genes, as shown in this study. The combined use of the vanB1-specific and the vanB consensus primers does not distinguish between vanB2 and vanB3 subtypes. However, sequencing of the vanB consensus primer target revealed vanB2 and vanB3 differences in the 10 vanB1 PCR-negative strains. Six vanB2 strains had a DNA sequence identical to that of the previously described vanB2 ligase gene (12). Single point mutations were detected in three vanB2 strains. The base pair transversion in TUH7-15 has been described previously (22). These strains should be classified as vanB2 subtype since they only differed from the previously described vanB2 gene by one or two nucleotides. In comparison, the TUH7-68 vanB3 strain showed 12 base pair substitutions in the corresponding part of the vanB ligase gene as described previously by Patel and coworkers (22).

The molecular heterogeneity of the vanB gene clusters has implications for the selection of diagnostic primers used to examine VanB-type resistance, as the primers must ensure the detection of all vanB subtypes. Our vanB consensus primers direct amplification of vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 genes, as shown in this study.

The original arguments for dividing the vanB ligase gene into three subtypes were based on sequence differences and the stability of these differences, at least in vanB1 and vanB2 ligase genes. Examination of sequence differences between the vanB subtypes (22) reveals that the vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 genes have 22, 6 to 9, and 19 conserved unique nucleotides, respectively. The present study suggests that the nucleotide sequences in the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region of the vanB gene cluster also display a corresponding vanB-subtype specifity (Fig. 2). (The vanB1 subtype has eight unique base pairs, the vanB2 subtype has a unique 5-bp deletion and three unique substitutions, and the vanB3 type strain has one unique base pair in this region. The vanB1 subtype has also lost one BspHI restriction site in the vanRB-vanSB gene area compared to the vanB2 and vanB3 subtypes, as shown by vanB long PCR-RFLP analysis.) The observed nucleotide sequence differences do not allow any conclusions to be made with regard to which vanB subtype should be considered the ancestral vanB gene cluster. However, the vanB2 ligase gene sequence seems to be less conserved than the vanB1 ligase gene (reference 22 and this study), indicating that the vanB2 gene cluster might be older than the vanB1 cluster in evolutionary terms. More sequence data are needed to support this observation. Since the vanB3-type gene cluster has been detected in only one strain, we do not know anything about the spread and sequence stability within this vanB subtype.

The vanB long PCR-RFLP analysis provides structural information on the vanB gene cluster that might be of interest in molecular epidemiological studies. The TUH7-15 RFLP-2* profile seems to be the result of a unique genetic event and is an example of the potential usefulness of such analysis.

The low MICs of vancomycin in some of the vanB1 and vanB2 strains are of clinical importance because they are difficult to detect by standard disk diffusion susceptibility testing. The Norwegian and Swedish strains (n = 4) showed MICs of vancomycin ranging from 12 to 32 μg/ml as determined by the E-test method. This could reflect the restricted use of glycopeptide antibiotics in these countries. It is difficult to assess how much the vanB gene contributes to the MIC (32 μg/ml) for the Norwegian E. gallinarum strain TUH7-16, as this strain also harbors a vanC1 gene as demonstrated by PCR (data not shown). Analyses of vanB or vanC1 gene expression have not been performed on this strain.

Our results have confirmed and extended earlier descriptions of vanB gene heterogeneity (12, 22). These observations are of importance when considering reservoirs and dissemination of VanB-type VRE. The sequence homology within the vanB1 and the vanB2 subtypes in genomically unrelated VRE strains indicates horizontal transmission of the vanB gene cluster as a major mode of dissemination of VanB-type glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. The high structural stability in the vanB gene clusters as shown by RFLP of long PCR amplicons indicates that the gene clusters have evolved from a common origin. The stable sequence differences between the vanB subtypes described in the present work and by Patel and coworkers (22) suggest a long-term separate evolution which might have occurred during selection in different ecological niches.

The sequence diversity in vanB resistance determinants is in contrast to the reported DNA sequence homogeneity in the vanA gene clusters (17, 22, 29). However, the Tn1546 or Tn1546-like elements conferring VanA-type resistance display structural heterogeneity (13–15, 17, 29) in contrast to the vanB gene clusters as shown in this study. The structural diversity in Tn1546 elements seems to be caused by deletions or insertions which may have occurred during single recombination events (14, 15, 17, 29). These rearrangements may have taken place recently. Several European studies have revealed a large environmental reservoir (17, 19, 20, 29) of VanA-type glycopeptide resistance determinants as well as VanA-type VRE in outpatients (18, 19, 28). A possible spread of VanA-type VRE through the food chain has been suggested (19, 28). To our knowledge, VanB-type VRE have only been detected in a hospital patient setting. The finding of at least three subtypes of the vanB gene cluster as described in the present work should encourage a search for different environmental reservoirs of vanB resistance determinants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Scandinavian Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, and the Odd Berg Foundation.

We thank P. R. Chadwick of North Manchester General Hospital, Manchester, United Kingdom, S. Harthug and A. Digranes of Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; I. Klare of the Robert Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany; E. B. Myhre of Lund University Hospital, Lund, Sweden; M. A. Pfaller and S. A. Marshall of the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City; and R. Patel of the Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, Minn.) for providing strains. We also thank Bjørg C. Haldorsen for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce J M, Opal S M, Chow J W, Zervos M J, Potter-Bynoe G, Sherman C B, Romulo R L C, Fortna S, Medeiros A A. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium with transferable vanB class vancomycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1148-1153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brynestad S, Iwanejko L A, Stewart G S A B, Granum P E. A complex array of Hpr consensus DNA recognition sequences proximal to the enterotoxin gene in Clostridium perfringens type A. Microbiology. 1994;140:97–104. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brynestad S, Synstad B, Granum P E. The Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin gene is on a transposable element in type A human food poisoning strains. Microbiology. 1997;143:2109–2115. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carias L L, Rudin S D, Donskey C J, Rice L B. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4426–4434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4426-4434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark N C, Cooksey R C, Hill B C, Swenson J M, Tenover F C. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:24–27. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.24-27.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evers S, Courvalin P. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanSB-VanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1302-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evers S, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. Sequence of the vanB and ddl genes encoding D-alanine:D-lactate and D-alanine:D-alanine ligases in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583. Gene. 1994;140:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evers S, Sahm D F, Courvalin P. The vanB gene of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583 is structurally related to genes encoding D-Ala:D-Ala ligases and glycopeptide-resistance proteins VanA and VanC. Gene. 1993;124:143–144. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facklam R R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gold H S, Ünal S, Cercenado E, Thauvin-Eliopoulos C, Eliopoulos G M, Wennersten C B, Moellering R C., Jr A gene conferring resistance to vancomycin but not teicoplanin in isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium demonstrates homology with vanB, vanA and vanC genes of enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1604–1609. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haaheim H, Dahl K H, Simonsen G S, Olsvik Ø, Sundsfjord A. Long PCRs of transposons in the structural analysis of genes encoding acquired glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. BioTechniques. 1998;24:432–437. doi: 10.2144/98243st02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handwerger S, Skoble J. Identification of chromosomal mobile element conferring high-level vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2446–2453. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handwerger S, Skoble J, Discotto L F, Pucci M J. Heterogeneity of the vanA gene cluster in clinical isolates of enterococci from the northeastern United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:362–368. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanrahan J A, Hoyen C, Rice L B. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Evidence for the geographic dispersion of a transferable mobile element conferring resistance to ampicillin and vancomycin in VanB E. faecium, abstr. C-91; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen L B, Ahrens P, Dons L, Jones R N, Hammerum A M, Aarestrup F M. Molecular analysis of Tn1546 in Enterococcus faecium isolated from animals and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:437–442. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.437-442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordens J Z, Bates J, Griffiths D T. Faecal carriage and nosocomial spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:515–528. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klare I, Heier H, Claus H, Böhme G, Marin S, Seltmann G, Hakenbeck R, Antanassova V, Witte W. Enterococcus faecium strains with vanA-mediated high-level glycopeptide resistance isolated from animal foodstuffs and fecal samples of humans in the community. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:265–272. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klare I, Heier H, Claus H, Witte W. Environmental strains of Enterococcus faecium with inducible high-level resistance to glycopeptides. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;106:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray B E, Singh K V, Heath J D, Sharma B R, Weinstock G M. Comparison of genomic DNAs of different enterococcal isolates using restriction endonucleases with infrequent recognition sites. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2059–2063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2059-2063.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel R, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Steckelberg J M, Kline B, Cockerill F R., III DNA sequence variation within vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC2/3 genes of clinical Enterococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:202–205. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Conjugal transfer of the vancomycin resistance determinant vanB between enterococci involves the movement of large genetic elements from chromosome to chromosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:359–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1547, a composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene. 1996;172:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quintiliani R, Jr, Evers S, Courvalin P. The vanB gene confers various levels of self-transferable resistance to vancomycin in enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1220–1223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahm D F, Kissinger J, Gilmore M S, Murray P R, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Auwera P, Pensart N, Korten V, Murray B E, Leclercq R. Influence of oral glycopeptides on the fecal flora of human volunteers: selection of highly glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodford N, Adebiyi A-M A, Palepou M-F I, Cookson B D. Diversity of VanA glycopeptide resistance elements in enterococci from humans and nonhuman sources. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:502–508. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodford N, Jones B L, Baccus Z, Ludlam H A, Brown D F J. Linkage of vancomycin and high-level gentamicin resistance genes on the same plasmid in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:179–184. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]