Abstract

The meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrinato cobalt(II) complex [Co(TMFPP)] was synthesised in 93% yield. The compound was studied by 1H NMR, UV-visible absorption, and photoluminescence spectroscopy. The optical band gap Eg was calculated to 2.15 eV using the Tauc plot method and a semiconducting character is suggested. Cyclic voltammetry showed two fully reversible reduction waves at E1/2 = −0.91 V and E1/2 = −2.05 V vs. SCE and reversible oxidations at 0.30 V and 0.98 V representing both metal-centred (Co(0)/Co(I)/Co(II)/Co(III)) and porphyrin-centred (Por2−/Por−) processes. [Co(TMFPP)] is a very active catalyst for the electrochemical formation of H2 from DMF/acetic acid, with a Faradaic Efficiency (FE) of 85%, and also catalysed the reduction of CO2 to CO with a FE of 90%. Moreover, the two triarylmethane dyes crystal violet and malachite green were decomposed using H2O2 and [Co(TMFPP)] as catalyst with an efficiency of more than 85% in one batch.

Keywords: cobalt(II) porphyrins, cyclic voltammetry, electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution, electroreduction CO2 to CO, catalytic degradation of dyes

1. Introduction

Inspired by nature that is using metalloporphyrins as antennae molecules, redox shuttles and redox and photo catalysts [1], researchers have tried to use artificial porphyrin complexes for various purposes in the last decades [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Cobalt porphyrins provide a rich electrochemistry consisting of both metal- (Co(I)/Co(II)/Co(III) and porphyrin-centred redox processes. By variation of the substituents on the phenyl core of the porphyrin ligands, these processes can cover a huge range of potentials [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Moreover, there are one or two axial positions available for binding small molecules [10,11,12,26,27,28,29]. Both properties make Co porphyrins very suitable for redox catalysis [22,23,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

In view of the climate crisis, the photochemical or electrochemical conversion of CO2 and H2O into energy-rich fuel products such as methanol [30,32,33] or dihydrogen (H2) [45,46,47] are important goals, and cobalt porphyrin complexes have been studied as catalysts for the CO2 reduction [30,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,44] and the H2 evolution [18,41,42,48], besides other important redox processes such as O2 reduction [19,23,49,50,51,52,53,54], O2 evolution reaction (OER) [49,55], and interesting organic redox transformations [56,57,58,59,60].

The potential of the CO2 reduction is strongly connected to the presence of protons [7,40]. However, fine-tuning of the reduction potentials of Co porphyrins is easily possible through substitution on the ligand core. The workhorses among the porphyrin ligands, the 5,10,15,20-tetraphenyl-porphyrins or meso-tetrakis(phenyl)porphyrins (TPP) have been varied in this respect to a large extent at the phenyl and pyrrole positions and these Co(TPP) complexes show reduction potentials in the range of −0.5 to −1.5 V vs. the SCE (saturated calomel electrode) [17,18,23,24,25,30,32,40,44,61,62]. The NHE potentials are converted into the current SCE scale by subtracting about 240 mV, while SCE differs from the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple by +160 mV [63]. As an example, extension of the π-conjugation in the Co(TPP) system, generating the Co(II)(meso-tetrakis(4-(pyren-1-yl)phenyl)porphyrin), allowed to move the reduction potential to higher values (easier reduction), which allowed the operation at −0.6 V, a high Faradaic efficiency (FE) for CO production with a high turnover frequency of 2.1 s−1 [32]. Co(II)(TPP) complexes in composite materials have also been used for CO2 reduction [34,37,64].

Electrochemical hydrogen production suffers from a huge overpotential of the so-called hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) for many materials, and elemental platinum was the first choice for a long time [45,46,47]. In the quest to replace this expensive metal and create molecular redox catalysts allowing the operation of cheaper electrode materials, complexes of abundant transition metals [47,65,66,67,68] containing various ligands including Co porphyrins have been synthesised [18,41,45,47,48,56,66,67,68,69,70]. For example, in a benchmarking work, the so-called hangman porphyrin which contains a proton-transferring COOH group in close proximity to the Co centre allowed very efficient HER catalysis with PhCOOH as substrate at a proton transfer (PT) rate of 3.10−6 s−1 and an electron transfer (ET) rate constant of 8.5 10−6 s−1 [69]. In a very early study using Co porphyrins containing meso-tetrakis(N,N,N-trimethylanilinium-4-yl)porphine chloride, meso-tetrapyrid-4-yl-porphine, and meso-tetrakis(N-methylpyridinium-4-yl)porphine chloride, H2 production from aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) on a Hg pool electrode at −0.95 V reached almost 100% FE [70]. In the same work, the Co(I) species was identified to react very rapidly with protons: Co(I) +H+ ⇆ Co(II) + ½ H2, while the formation of H2 from Co(III)-H− intermediates is slower.

Amongst other organic redox transformations, the electrochemically or photochemically initiated decomposition of organic dyes in waste water is another increasingly important research field in recent years [5]. Recently, Zn(II) [12,15,71,72] and Co(II) porphyrins [10,11,26,73] have been used as catalysts in the degradation of organic dyes with H2O2. In view of the first oxidation potential of Co(TPP) complexes lying in the range of 0.1 to 0.75 V vs. SCE [10,11,13,16,17,22,24,25,26,61,62], their high reactivity in radical-based organic transformations [14,58,59,60] is not unexpected and a very recent study on a (5,10,15,20-tetrakis(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)porphyrinato)cobalt(II) has revealed some mechanistic details in such decomposition reactions using H2O2 [73].

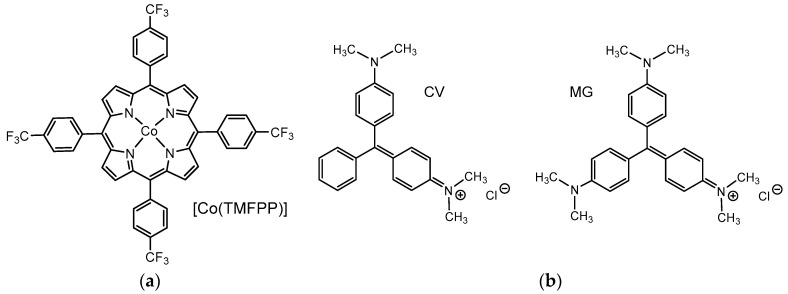

We recently stepped on the Co(II) complex [Co(TMFPP)] (H2TMFPP = meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrin) which has previously been reported [21,29,53,54,59,60,74,75], for example, as catalyst for the direct C–H arylation of benzene [60]. This motivated us to study its use as redox catalyst for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution, the electroreduction of CO2 to CO, and the catalytic degradation and adsorption of the dyes crystal violet (CV) and malachite green (MG; Scheme 1). We synthesised the compound in a slightly modified procedure and characterised it by elemental analysis, 1H NMR, FT-IR, absorption and photoluminescence spectroscopy. We briefly report on basic spectroscopic and electrochemical properties, as this has not been done before, and then report in detail on the electrocatalytical experiments.

Scheme 1.

Structures of (a) [Co(TMFPP)], (b) crystal violet (CV) and malachite green (MG).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and 1H NMR Spectroscopy

The free-base porphyrin meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrin (H2TMFPP) was synthesised modifying a literature method [76] (see Section 3). Elemental analysis and 1H NMR confirmed the purity of the material. The meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrinato Co(II) [Co(TMFPP)] (Scheme 1) was synthesised using the so-called DMF method [77]. Elemental analysis and MS confirmed its purity. FT-IR (Figure S1, Supplementary Material) and UV-vis absorption (Figure 1) and 1H NMR data (Figure S2) agree with the reported data [51]. In keeping with the paramagnetic character of the Co(II) d7 system, we obtained broadened 1H NMR signals at δ = 15.71 ppm for the β-pyrrole protons and at 12.96 and 9.92 ppm for the phenyl atoms [10,11,26,54,78].

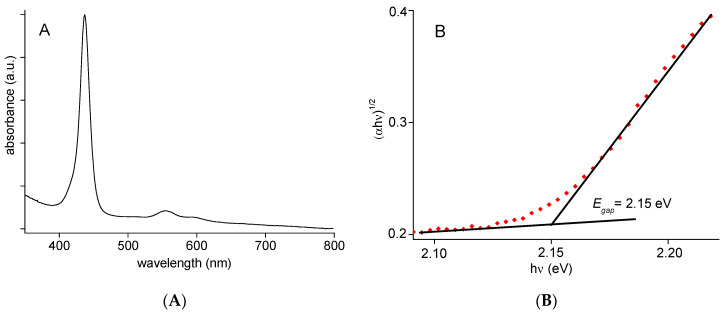

Figure 1.

UV/vis absorption spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)] in CH2Cl2 (A); curve of (αhυ)2 as a function of photon energy E (B).

2.2. Photophysical Properties

The UV-vis absorption spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)] in CH2Cl2 solution showed a Soret band at 437 nm and a Q band at 554 nm in line with similar Co(II) porphyrins (Figure 1A) [51,53,79,80,81,82]. The optical band gap (Eg), which is the energy difference between the HOMO and LUMO levels, was determined from the UV-vis absorption spectrum. The values of the optical band gap (Eg) of [Co(TMFPP)] were determined using the Tauc relation (Figure 1B). The Eg value was 2.15 eV, which is in the normal range for Co metalloporphyrins [53,80].

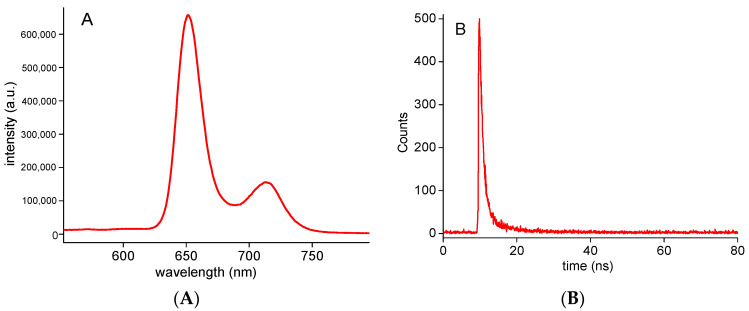

The photoluminescence spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)] in CH2Cl2 at room temperature is shown in Figure 2. Upon excitation at 405 nm, an emission with maxima at 653 and 718 nm is observed and can be attributed to the S1[Q(0,0)]→S0 and S1[Q(0,1)]→S0 transitions in line with previous studies on [Co(TPP)] [80,83,84,85] and related [Zn(TPP)] [12,15,72,81]. The photoluminescence quantum yield (ΦPL) for [Co(TMFPP)] is 0.041. The singlet excited-state lifetimes were measured by the single-photon counting technique, and the fluorescence decays were fitted to simple exponentials with 2 ns lifetime (Figure 2B), which lies in a typical range for [Co(TPP)] derivatives [80,83].

Figure 2.

Emission spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)] in 10−6 M solutions in CH2Cl2 at room temperature (A), excited at 405 nm; fluorescence decay profile (B).

2.3. Electrochemical Characterisation

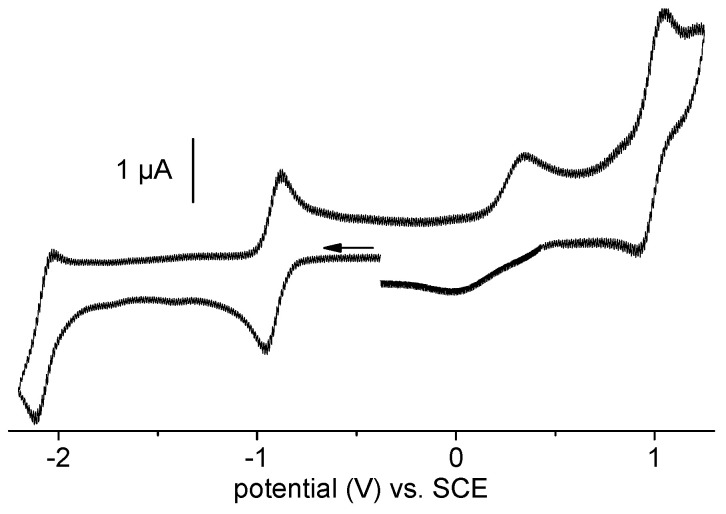

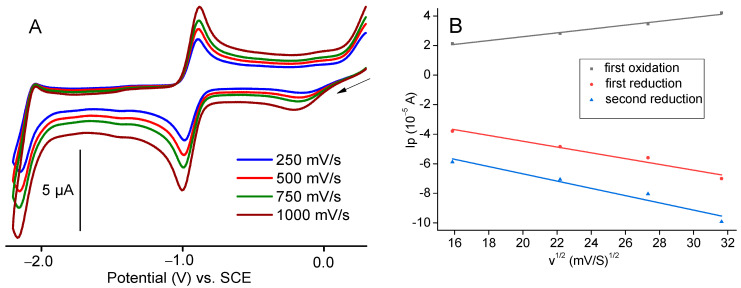

Cyclic voltammograms of [Co(TMFPP)] were recorded in DMF, which is a potential donor ligand and is thus prone to coordinate to the Co centre after oxidation, as has been found for most square planar coordinated M(II) porphyrins [58,59]. Two reversible one-electron reductions were found for [Co(TMFPP)] at E1/2 = −0.91 V and E1/2 = −2.05 V (Figure 3). While it is generally accepted to assign the first wave to the Co(II)/Co(I) redox couple [24,61,62,86,87], the second was earlier discussed as porphyrin-centred (Por2−/Por3−), in line with reports on the unsubstituted [Co(TPP)] [24,61,62,86]. Alternatively, a Co(0) species after a Co(I)/Co(0) reduction has been discussed [20,88,89]. The latter description is supported by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy [89].

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammogram of [Co(TMFPP)] in 0.1 M nBu4NBF4/DMF, recorded at 100 mV s−1.

A first one-electron oxidation at 0.30 V that can be assigned to the Co(II)/Co(III) redox couple is broadened, but reversible. The broadening is due to the coordination of DMF after oxidation, as mentioned above. This wave is followed by a slightly larger reversible wave at 0.98 V, which is assigned to a porphyrin-centred process (Por2−/Por1−) in line with previous reports [21,24,61,62,85,86,87]. For the 4-MeO substituted derivative, a third oxidation at 1.09 V following the second oxidation at 0.92 V was reported [24,62], and for the 2,5-MeO substituted complex, second and third oxidation waves were observed at 0.62 and 1.15 V [73]. This lets us assume that, for [Co(TMFPP)], both these two porphyrin-centred processes are merged into one (larger) wave.

For [Co(TPP)] in DMF potentials of −1.88, −0.77, 0.30, and 1.05 V were previously reported for the same processes [24], while the 4-MeO substituted derivative showed −0.98 V, 0.38 V, and 0.92 V for the first reduction and the two oxidations. This means that the introduction of the four CF3 groups does not markedly affect the metal-centred first oxidation and reduction.

For a fully homogeneous diffusion-controlled electrochemical process, the peak current (Ip) for a Faradaic electron transfer varies linearly with the square root of scan rate (ν1/2). From the slope of the Ip vs. ν1/2 plot, the diffusion coefficient (D) can be determined using Randles–Sevcik equation (Equation (1)):

| Ip = 0.4463 F A (F/RT)1/2 D1/2 np3/2 [C0] ν1/2 | (1) |

where Ip is the peak current, F is the Faraday constant (F = 96485 C mol−1), R is the universal gas constant (R = 8.314 J K−1 mol−1), T = 298 K, np is the number of electrons transferred (here, np = 1), A is the active surface area of the electrode (0.00785 cm2). Note that our plots are reported as a function of the current density, bypassing the need of the area value in Equation (1). D is the diffusion coefficient for the complex, [C0] is the concentration of the catalyst (here [C0] = 1 mM), and ν is the scan rate in V s−1. The diffusion coefficient (D) was calculated from the slope of Ip vs. ν1/2 (Figure 4, right). The diffusion coefficient D for the Co(II)/Co(I) reduction is 1.98 × 10−7 cm S−1, while the value for the Co(II)/Co(III) oxidation is slightly larger with 9.5 × 10−7 cm S−1, in keeping with the assumed additional DMF ligand for the oxidised complex [Co(TMFPP)(DMF)]+. The diffusion coefficient D for the second reduction process with 1.1 × 10−8 cm S−1 is smaller than the value for the first reduction, which is due to the increased negative charge, but still quite large.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of [Co(TMFPP)] in 0.1 M nBu4NBF4/DMF recorded at different scan rates (A). Peak currents vs. square roots of the scan rate for the two reduction processes (B).

2.4. Electrocatalytic H2 Production in the Presence of Acetic Acid (AcOH)

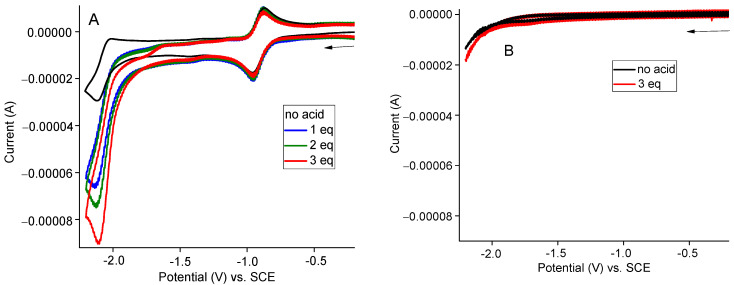

We studied the electrocatalytic activity of [Co(TMFPP)] in DMF/acetic acid due to better solubility in this mixture than in water (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of [Co(TMFPP)] (1 mM) in 0.1 M nBu4NBF4/DMF recorded in the absence (black trace) or in the presence of 1 to 3 eq. CH3COOH in DMF at 100 mV s−1 (A), Blank test without catalyst (B).

On first view, our cyclic voltammetric plots show that, upon addition of acid, a catalytic current appears at the second reduction wave of [Co(TMFPP)] (Figure 5), while the first wave remains unchanged. The FE in H2 production (quantified by GC) of [Co(TMFPP)] at −2.3 V was determined after 2 h to 85%. For the previously reported [Co(TMAP)](ClO4)2 (H2TMAP = meso-tetrakis(N,N,N-trimethylanilinium-4-yl)porphine), [Co(TMPyP)](ClO4)2 (meso-tetrakis(N-methylpyridinium-4-yl)porphine) and [Co(TpyP)] (meso-tetrapyrid-4-ylporphine), FEs of >90% were found [70].

Mechanistically speaking, it seems that the first reduced species which we formally describe as [Co(I)(Por2−]− is not catalytically very active, which would stand in contrast to previous mechanistic studies [18,70] which proposed that the reduced Co(I) species reacts with protons forming Co(II) and Co(III) species (Equations (2) to (6)) [70].

| Co(I) +H+ ⇆ Co(II) + ½ H2 | (2) |

| Co(II) +e− ⇆ Co(I) | (3) |

| Co(I) +H+ ⇆ Co(III)H− | (4) |

| Co(III)H− +H+ ⇆ H2 + Co(III) | (5) |

| Co(III)H− +H+ ⇆ ½ H2 + Co(II) | (6) |

Our experiments indicate that only after the second reduction, the resulting [Co(0)(Por2−)]2− species is active in reducing protons. In the abovementioned study on the complexes [Co(TMAP)](ClO4)2, [Co(TMPyP)](ClO4)2, and [Co(TpyP)] catalytic currents representing the proton reduction were observed at −0.95 V [70]. In a recent study, very different behaviour was found for the catalytic proton reduction using [Co(TXPP)] (H2TXPP = meso-tetra-para-X-phenylporphin) catalysts [18]. For X = Cl = catalytic waves were observed at around −2 V comparable to our findings, while for X = OMe, the H2 evolution was observed already at around −1 V. Thus, we can conclude that the substitution pattern of the meso-tetraarylporphin ligands has a strong impact on the observed catalytic potential. Depending on these patterns, the Co(TPP) derivatives might be an active catalyst in the Co(I) oxidation state or alternatively might need to reach the Co(0) state after the second reduction for efficient proton reduction.

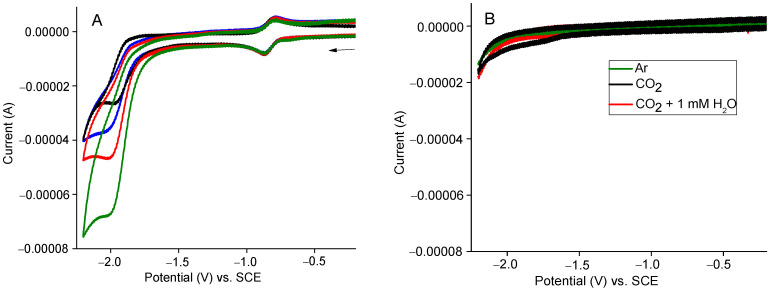

2.5. Electroreduction CO2 to CO

[Co(TMFPP)] was further tested for the electrocatalytic CO2 reduction, in CO2-saturated DMF, with water added as a proton source. Cyclic voltammograms of [Co(TMFPP)] in the presence of CO2 showed marked catalytic currents at potentials at around −2 V, with the presence of water being beneficial (Figure 6A, green and red trace). No activity was found in the absence of the catalyst (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of 1 mM solutions of [Co(TMFPP)] in 0.1 M nBu4NBF4/DMF in the presence of H2O (Black: in Ar, Red: in CO2, Blue: in Ar and 1 mM of H2O and green: in CO2 and 1mM of H2O) (A). Blank test without catalyst (B).

Controlled potential electrolysis at −2.25 V for 2 h in aqueous DMF under a CO2 atmosphere gave a FE of 90%; GC confirmed the production of CO and only traces of H2. Remarkably, not even traces of the very common products formate and methanol were found.

[Co(TPP)] was reported with an FE of 50% for CO alongside with traces of H2 (FE = 2%), formate (4%), acetate (2%) and oxalate (0.4%) on electrolysis at −1.95 or −2.05 V vs. SEC in DMF [88]. When immobilised on carbon nanotubes, [Co(TPP)] allowed an efficiency of 83% at −1.15 V or 93% at −1.35 V [88] and the authors could circumvent the rapid catalyst decomposition monitored by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy.

Thus, our unsupported [Co(TMFPP)] is markedly superior in terms of efficiency and selectivity to the standard [Co(TPP)] and support with an electron-conducting material might pave the way to operate the [Co(TMFPP)] at less negative potentials. Importantly, also here, only the second reduction wave produces the catalytically active species, which we describe as Co(0) complex.

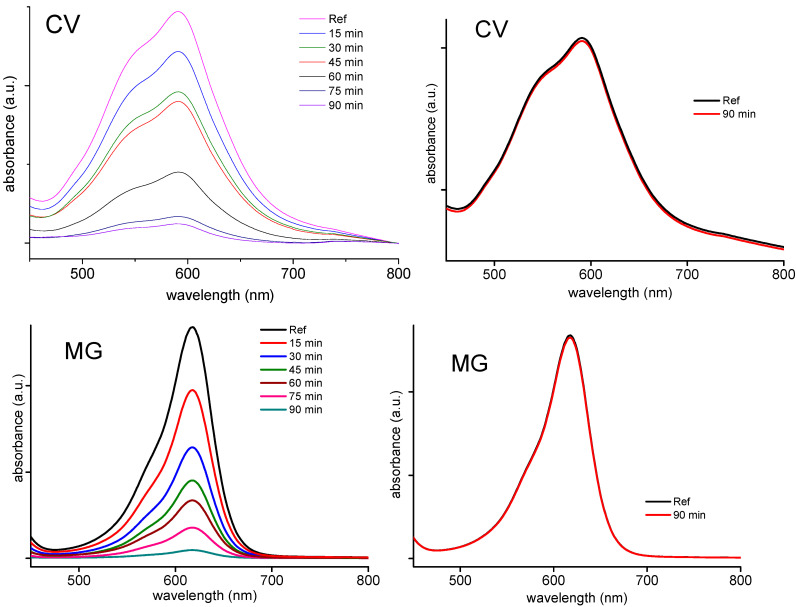

2.6. Catalytic Oxidative Degradation of Dyes

To further evaluate the catalytic properties of [Co(TMFPP)], we studied the decomposition of the two dyes malachite green (MG, 4-([4-(dimethylamino)phenyl](phenyl)methylidene)-N,N-dimethylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-iminium chloride) and crystal violet (CV, 4-(bis[4-(dimethylamino)phenyl]methylidene)-N,N-dimethylcyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-iminium chloride; see Scheme 1) in the presence of H2O2. The MG cation shows a very intense green colour with an absorption band centred at 621 nm, while the CV cation has a very intense violet colour and the absorption maximum of the most intense band at 591 nm (Figure 7). Upon addition of H2O2 in the presence of [Co(TMFPP)], the dyes were rapidly decomposed, as the UV-vis absorption traces showed (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Evolution of the absorbance of malachite green (MG) and crystal violet (CV) over time using 3 mL H2O2 and 5 mg [Co(TMFPP)] and dye concentrations of 25 mg L−1, in H2O at pH = 8 and T = 298 K (left). Blank tests without catalyst (right).

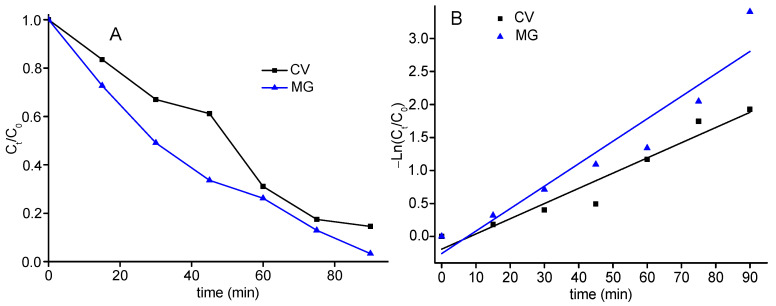

To further study the reaction kinetics of the degradation, the Ct/C0 ratios were varied and a pseudo-first order rate constant k was calculated using Equation (7) (Langmuir–Hinshelwood):

| ln C0/Ct = k t | (7) |

Ct and C0 are the dye concentrations at times t and 0, k is the first-order rate constant. The fit of the pseudo kinetic model is shown in Figure 8, and the rate constants of degradation (k) were calculated to 0.023 and 0.034 min−1 for CV and MG, respectively.

Figure 8.

Kinetics of [Co(TMFPP)]-catalysed degradation of malachite green (MG), and crystal violet (CV) through H2O2 in aqueous solution: changes in Ct/C0 versus time (A) and changes in ln(Ct/C0) versus time (B).

The two triarylmethane dyes crystal violet and malachite green were decomposed using H2O2 and [Co(TMFPP)] as catalyst with an efficiency of more than 85% (C0 = 25 mg/L, pH = 8, H2O2 concentration = 3 mL/L, T = 25 °C). Two 4-cyanopyridine complexes of the type [Co(II)(Por)(4-CNpy)] (Por = meso-tetrakis(para-methoxyphenyl)porphyrinato and meso-tetra(para-chlorophenyl)porphyrin) as catalysts in the degradation of organic dyes using H2O2 gave a degradation efficiency of more than 78% [10,11,26,73], while recently reported Zn(II) triazole-substituted meso-arylsubstituted porphyrin complexes gave efficiencies of up to 50% [12,15,71,72]. This shows that Co(II) porphyrins are generally superior to Zn(II) derivatives in line with the assumption that the first reduction is cobalt-centred (Co(II)(Co(I)).

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

All reagents and solvents were purchased from ACROS ORGANICS (Geel, Belgium) or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Solvents were purified using literature methods [90]. Silica gel 150 (35–70 μm particle size, Davisil) was used for final purification of the products. Double-distilled water was used in the experiments.

3.2. Synthetic Procedures

3.2.1. Synthesis of the meso-Tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrin (H2TMFPP)

Note that 3.65 g of 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde (21 mmol) were dissolved in propionic acid (100 mL) in air and heated to 120 °C. In addition, 1.4 g of pyrrole (1.35 mL, 21 mmol) were added dropwise to the reaction and the mixture was kept at 120 °C for a further 45 min. The resulting solution was allowed to cool and the tarry mixture was filtered to give a black solid, which was rinsed with water (5 × 100 mL) and (5 × 100 mL) n-hexane and finally dried under vacuum with a yield of 1.25 g (1.4 mmol, 27%). Anal. calcd. for C48H26F12N4 (886.74): C, 65.02; H, 2.96; N, 6.32; found: C, 65.21; H, 2.85; N, 6.43%; MS (ESI(+), CH2Cl2): m/z = 886.68 for [M]+; UV-vis (CH2Cl2): λmax (ε.10−3M−1cm−1): 424(370), 519(85), 557(39), 591(30), 651(25); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.95 (s, 8H, β-pyrrole), 8.13 (s, 8H, arylH), 7.77 (s, 8H, arylH) ppm. FT-IR (solid, , cm−1); 3290 (νNH), 2922 (νCH), 1518 (νC=N/νC=C), 965 (δCCH).

3.2.2. Synthesis of the meso-Tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrinato Co(II) [Co(TMFPP)]

An amount of 200 mg (0.225 mmol) H2TMFPP was dissolved in 100 mL of DMF. The solution was brought to reflux under magnetic stirring. After dissolution of H2TMFPP or H2TTMPP, 53 mg (0.222 mmol) CoCl2.6H2O were added. The reaction mixture was left under stirring for 3 h. Thin-layer chromatography (Al2O3, with CH2Cl2 as eluent) showed no free-base porphyrin- at this level. After this, the solution was brought to 45–55 °C, and 100 mL H2O were poured in. The resulting solid was filtered, washed with n-hexane and finally dried under vacuum to yield 195 mg (206 mmol, 93%) of product. Anal. calcd. for C48H24N4F12Co (943.66): C, 61.09; H, 2.56; N, 5.94; found: C, 60.99; H, 2.59; N, 6.02%; MS (ESI(+), CH2Cl2): m/z = 943.62 for [M]+; UV-vis (CH2Cl2): λmax (ε.10−3M−1cm−1): 414(380), 533(54), 568 sh(16), 437(385), 554(30), 592(20); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 15.71 (s, 8H, β-pyrrole); 12.96 (s, 8H, arylH); 9.92 (s, 8H, arylH); FT-IR (solid, , cm−1); 2959 (νCH porphyrin), 1498 (νC=N/(νC=C porphyrin), 1021 (δCCH porphyrin).

3.3. Instrumentation

UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded on a WinASPECT PLUS (validation for SPECORD PLUS version 4.2, WinASPECT, Jena, Germany) scanning spectrophotometer using 10 mm path length cuvettes. 1H NMR spectra were measured on Bruker DPX 500 spectrometers (Bruker, Rheinhausen, Germany) in CDCl3 with the solvent peak as an internal standard. FT-IR spectra were measured on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two FT-IR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Darmstadt, Germany). Elemental analysis and mass spectrometry were carried out in the nanobio chemistry platform of the ICMG, Grenoble, France. A Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific, 59120 Loos, France) was used to record photoluminescence (PL) spectra at room temperature in CH2Cl2. PL quantum yield (ΦPL) was determined using the optical method [12] with [Zn(TPP)] as standard (ΦPL = 0.031). The luminescence lifetime detection was performed upon irradiation at λ = 405 nm. The luminescence decay was analysed using the PicoQuant FLUOFIT software (PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany) [15].

3.4. Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry experiments were performed using a CH-660B potentiostat at room temperature. All measurements were performed in DMF with a solute concentration of approximately 10−3 M and nBu4NBF4 (0.1 M) as supporting electrolyte. A three-electrode cell was set up with a glassy carbon working electrode, a Pt wire as counter electrode, and an Ag/AgNO3 reference electrode. Potentials were converted into values for the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) by applying Equation (8) [11,63,91,92]:

| E(SCE) = E(Ag/AgNO3) + 360 mV | (8) |

3.5. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction

The experiments were performed at room temperature under a CO2 atmosphere in a conventional three-electrode cell sealed with Apiezon M vacuum grease. A glassy carbon electrode plate (2 cm2, 0.25 mm thickness) was used as the working electrode in the cathodic compartment. A 0.5 mm diameter platinum wire (10 cm length) was used as the counter electrode in the anodic compartment. The cell was purged with Ar or CO2 for a minimum of 15 min before controlled potential electrolysis was carried out. Constant magnetic stirring was applied during electrolysis.

3.6. Gas Detection

Gas analyses were performed using a GC/MS gas chromatography (Perkin Elmer Clarus 560) instrument with a thermal conductivity detector fitted with RT-QPlot pre column + molecular sieve 5Å column. The temperature was held at 150 °C for the detector and 80 °C for the oven. The carrier gas was helium. Manual injections of 100 μL were performed during the experiment via a gas-tight Hamilton microsyringe. The total volume of the cell was 173 mL.

3.7. Faradaic Efficiency Calculation

The Faradaic Efficiency (FE) of the CO2 reduction or hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) was calculated using Equation (9):

| FE = Z n F/Q | (9) |

where Z is the amount of product in mol, n is the number of the electrons (2 for both CO and H2), F is the Faraday constant, and Q is the number of electrons (or charge) passed through the solution during electrolysis (I t).

3.8. Catalytic Dye Degradation

In a typical investigation, to a 10 mL aqueous solution of the dyes crystal violet (CV) and malachite Green (MG) (20 mg L−1), 3 mL/L of H2O2 (30 wt %) were added. Next, 5 mg of the catalyst were added to this mixture at a stirring speed of 250 rpm. The reaction solution was pipetted into a quartz cell and UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded at different reaction times. Blank experiments were carried out to confirm that the reactions did not take place without catalyst in the presence of H2O2.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrinato cobalt(II) complex [Co(TMFPP)] was synthesised via modified literature methods in an excellent yield of 93% from the free-base porphyrin meso-tetrakis(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)porphyrin (H2TMFPP). Elemental analysis, FT-IR, and 1H NMR spectroscopy confirmed the molecular entities. UV-vis absorption spectroscopy localised the Soret band at 437 nm and the Q band at 554 nm. The optical band gap Eg was calculated using the Tauc plot method to 2.15 eV. The (αhυ)2 over E plot suggests a semiconducting behaviour of the material. Cyclic voltammetry of the title compound showed two fully reversible reduction waves. Both the first wave, observed at E1/2 = −0.91 V vs. SCE, and the second at E1/2 = −2.05 V are ascribed to cobalt-centred processes Co(II)/Co(I) and Co(I)/Co(0), respectively. The first oxidation wave at around 0.3 V is metal-centred Co(II)/Co(III) and broadened through the interaction of the DMF solvent with the oxidised complex. A second oxidation is following at 0.98 V, which is presumably due to the redox couple Por2−/Por−. [Co(TMFPP)] is a very active catalyst for the electrochemical formation of H2 from DMF/acetic acid, with a Faradaic Efficiency (EF) of 85% at a working potential of −2.3 V. This is in line with [Co(0)(Por2−)]2− being the active species. The complex also catalysed the reduction of CO2 to CO in aqueous DMF under CO2 atmosphere with a high EF of 90% and only traces of H2 by-product, making our derivative superior to the standard [Co(TPP)]. Also here, catalytic currents are only observed at potentials coinciding with the second reduction potential in the voltammograms, thus the same [Co(0)(Por2−)]2− species seems to be active as for the proton reduction. Moreover, the two triarylmethane dyes crystal violet and malachite green were decomposed in aqueous solution using H2O2 and [Co(TMFPP)] as catalyst with an efficiency of more than 85% in one batch. Given the high stability of the complex and the relatively easy preparation with excellent yields, this makes [Co(TMFPP)] a versatile catalyst for important electrocatalytic reductions and oxidations. The performance on the cathodic side might be improved with the goal of less negative working potentials in future work by blending the complex with electroactive materials such as carbon nanotubes, or by immobilising the complex directly on electrodes.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Supplementary Materials

The following information is available online. Figure S1: FT-IR spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)]. Figure S2: 1H NMR spectrum of [Co(TMFPP)] (C ~10−3 M) in CDCl3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: H.N. and M.G.; methodology: H.N., F.L., M.G. and A.K.; investigation: M.G. and F.M.; resources: H.N. and F.L.; data curation: M.G., F.L. and A.K.; visualisation: M.G. and A.K.; supervision and project administration: H.N.; manuscript original draft: M.G.; manuscript editing: M.G., F.M. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for the financial support. A.K. thanks additionally the University of Cologne for support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kaim W., Schwederski B., Klein A. Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic Elements in the Chemistry of Life—An. Introduction and Guide. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma P.K., Sawant S.D. Unravelling reaction selectivities via bio-inspired porphyrinoid tetradentate frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022;450:214239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishiori D., Wadsworth B.L., Reyes Cruz E.A., Nguyen N.P., Hensleigh L.K., Karcher T., Moore G.F. Photoelectrochemistry of metalloporphyrin--modified GaP semiconductors. Photosynth. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11120-021-00834-2. online . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lomova T. Recent progress in organometallic porphyrin-based molecular materials for optical sensing, light conversion, and magnetic cooling. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35:e6254. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey P.D. Porphyrin-based MOFs as heterogeneous photocatalysts for the eradication of organic pollutants and toxins. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines. 2021;25:583–604. doi: 10.1142/S1088424621300020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathew D., Sujatha S. Interactions of porphyrins with DNA: A review focusing recent advances inchemical modifications on porphyrins as artificial nucleases. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021;219:111434. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang R., Warren J.J. Recent Developments in Metalloporphyrin Electrocatalysts for Reduction of Small Molecules: Strategies for Managing Electron and Proton Transfer Reactions. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:293–302. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202001914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faustova M., Nikolskaya E., Sokol M., Fomicheva M., Petrov R., Yabbarov N. Metalloporphyrins in Medicine: From History to Recent Trends. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020;3:8146–8171. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun T., Zhang Z., Xu J., Liang L., Mai C.-L., Ren L., Zhou Q., Yu Y., Zhang B., Gao P. Structural, photophysical, electrochemical and spintronic study of first-row metal Tetrakis(meso-triphenylamine)-porphyrin complexes: A combined experimental and theoretical study. Dyes Pigm. 2021;193:109469. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2021.109469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guergueb M., Nasri S., Brahmi J., Al-Ghamdi Y.O., Loiseau F., Molton F., Roisnel T., Guerineau V., Nasri H. Spectroscopic characterization, X-ray molecular structures and cyclic voltammetry study of two (piperazine) cobalt(II) meso-arylporphyin complexes. Application as a catalyst for the degradation of 4-nitrophenol. Polyhedron. 2021;209:115468. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2021.115468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guergueb M., Nasri S., Brahmi J., Loiseau F., Molton F., Roisnel T., Guerineau V., Turowska-Tyrk I., Aouadi K., Nasri H. Effect of the coordination of π-acceptor 4-cyanopyridine ligand on the structural and electronic properties of meso-tetra(para-methoxy) and meso-tetra(para-chlorophenyl) porphyrin cobalt(II) coordination compounds. Application in the catalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. RSC Adv. 2020;10:6900–6918. doi: 10.1039/C9RA08504A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guergueb M., Brahmi J., Nasri S., Loiseau F., Aouadi K., Guerineau V., Najmudin S., Nasri H. Zinc(II) triazole meso-arylsubstituted porphyrins for UV-visible chloride and bromide detection. Adsorption and catalytic degradation of malachite green dye. RSC Adv. 2020;10:22712–22725. doi: 10.1039/D0RA03070H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhri N., Cong L., Bulbul A.S., Grover N., Osterloh W.R., Fang Y., Sankar M., Kadish K.M. Structural, Photophysical, and Electrochemical Properties of Doubly Fused Porphyrins and Related Fused Chlorins. Inorg. Chem. 2020;59:1481–1495. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pamin K., Tabor E., Gjrecka S., Kubiak W.W., Rutkowska-Zbik D., Połtowicz J. Three Generations of Cobalt Porphyrins as Catalysts in the Oxidation of Cycloalkanes. ChemSusChem. 2019;12:684–691. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201802198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soury R., Jabli M., Saleh T.A., Abdul-Hassan W.S., Saint-Aman E., Loiseau F., Philouze C., Nasri H. Tetrakis(ethyl-4(4-butyryl)oxyphenyl)porphyrinato zinc complexes with 4,4′-bpyridin: Synthesis, characterization, and its catalytic degradation of Calmagite. RSC Adv. 2018;8:20143–20156. doi: 10.1039/C8RA01134F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ke X., Kumar R., Sankar M., Kadish K.M. Electrochemistry and Spectroelectrochemistry of Cobalt Porphyrins with π--Extending and/or Highly Electron-Withdrawing Pyrrole Substituents, In Situ Electrogeneration of σ--Bonded Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018;57:1490–1503. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye L., Fang Y., Ou Z., Xue S., Kadish K.M. Cobalt Tetrabutano- and Tetrabenzotetraarylporphyrin Complexes: Effect of Substituents on the Electrochemical Properties and Catalytic Activity of Oxygen Reduction Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:13613–13626. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., Fu L.-Z., Yang L.-M., Liu X.-P., Zhan S.-Z., Ni C.-L. The impact of modifying the ligands on hydrogen production electro-catalyzed by meso-tetra-p-X-phenylporphin cobalt complexes, CoT(X)PP. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016;417:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.molcata.2016.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhutaeva G.V., Tarasevich M.R., Radina M.V., Chernyshova I.S. Composites Based on Phenyl Substituted Cobalt Porphyrins with Nafion as Catalysts for Oxygen Electroreduction. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2009;45:1080–1088. doi: 10.1134/S1023193509090146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein A. Spectroelectrochemistry of Metalloporphyrins. In: Kaim W., Klein A., editors. Spectroelectrochemistry. RSC Publishing; Cambridge UK: 2008. pp. 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryabova V., Schulte A., Erichsen T., Schuhmann W. Robotic sequential analysis of a library of metalloporphyrins as electrocatalysts for voltammetric nitric oxide sensors. Analyst. 2005;130:1245–1252. doi: 10.1039/b505284j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun H., Smirnov V.V., DiMagno S.G. Slow Electron Transfer Rates for Fluorinated Cobalt Porphyrins: Electronic and Conformational Factors Modulating Metalloporphyrin ET. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:6032–6040. doi: 10.1021/ic034705o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi N., Nevin W.A. Electrocatalytic Reduction of Oxygen Using Water-Soluble Iron and Cobalt Phthalocyanines and Porphyrins. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1996;10:579–590. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0739(199610)10:8<579::AID-AOC523>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker F.A., Beroiz D., Kadish K.M. Electronic Effects in Transition Metal Porphyrins. 2. The Sensitivity of Redox and Ligand Addition Reactions in Para-Substituted Tetraphenylporphyrin Complexes of Cobalt(II) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:3484–3489. doi: 10.1021/ja00428a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tezuka M., Ohkatsu Y., Osa T. Reduction and Oxidation Potentials of Metal-free and Cobalt Tetra(p-substituted phenyl)porphyrins. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976;49:1435–1436. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.49.1435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasri S., Hajji M., Guergueb M., Dhifaoui S., Marvaud V., Loiseau F., Molton F., Roisnel T., Guerfel T., Nasri H. Spectroscopic, Electrochemical, Magnetic and Structural Characterization of an hexamethylenetetramine Co(II) Porphyrin Complex – Application in the Catalytic Degradation of Vat Yellow 1 dye. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1231:129676. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Xing Y.-F., Wen J., Ma H.B., Wang F.-B., Xia X.-H. Axial ligands tailoring the ORR activity of cobalt porphyrin. Sci. Bull. 2019;64:1158–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doctorovich F., Bikiel D., Pellegrino J., Suárez S.A., Martí M.A. Stabilization and detection of nitroxyl by iron and cobalt porphyrins in solution and on surfaces. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines. 2010;14:1012–1018. doi: 10.1142/S1088424610002914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter-Addo G.B., Hodge S.J., Yi G.-B., Khan M.A., Ma T., Van Caemelbecke E., Guo N., Kadish K.M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Spectroelectrochemistry of Cobalt Porphyrins Containing Axially Bound Nitric Oxide. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:6530–6538. doi: 10.1021/ic960031o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usman M., Humayun M., Garba M.D., Ullah L., Zeb Z., Helal A., Suliman M.H., Alfaifi B.Y., Iqbal N., Abdinejad M., et al. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2: A Review of Cobalt Based Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Fuels. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2029. doi: 10.3390/nano11082029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marianov A.N., Kochubei A.S., Roman T., Conquest O.J., Stampfl C., Jiang Y. Modeling and Experimental Study of the Electron Transfer Kinetics for Non-ideal Electrodes Using Variable-Frequency Square Wave Voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 2021;93:10175–10186. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dou S., Sun L., Xi S., Li X., Su T., Fan H.J., Wang X. Enlarging the π-Conjugation of Cobalt Porphyrin for Highly Active and Selective CO2 Electroreduction. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:2126–2132. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marianov A.N., Kochubei A.S., Roman T., Conquest O.J., Stampfl C., Jiang Y. Resolving Deactivation Pathways of Co Porphyrin-Based Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction in Aqueous Medium. ACS Catal. 2021;11:3715–3729. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c05092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen X., Hu X.-M., Daasbjerg K., Ahlquist M.S.G. Understanding the Enhanced Catalytic CO2 Reduction upon Adhering Cobalt Porphyrin to Carbon Nanotubes and the Inverse Loading Effect. Organometallics. 2020;39:1634–1641. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jack J., Park E., Maness P.-C., Huang S., Zhang W., Ren Z.J. Selective ligand modification of cobalt porphyrins for carbon dioxide electrolysis: Generation of a renewable H2/CO feedstock for downstream catalytic hydrogenation. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2020;507:119594. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z.-j., Song H., Liu H., Ye J. Coupling of Solar Energy and Thermal Energy for Carbon Dioxide Reduction: Status and Prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:8016–8035. doi: 10.1002/anie.201907443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha S., Zhang R., Warren J.J. Low Overpotential CO2 Activation by a Graphite-Adsorbed Cobalt Porphyrin. ACS Catal. 2020;10:12284–12291. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c01367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdinejad M., Seifitokaldani A., Dao C., Sargent E.H., Zhang X.-a., Kraatz H.B. Enhanced Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 Catalyzed by Cobalt and Iron Amino Porphyrin Complexes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019;2:1330–1335. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b01900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu B., Xie W., Li R., Pan Z., Song S., Wang Y. How does the ligands structure surrounding metal-N4 of Co-based macrocyclic compounds affect electrochemical reduction of CO2 performance? Electrochim. Acta. 2019;331:135283. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamoto K., Asahi R. Water Facilitated Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 on Cobalt-Porphyrin Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:9944–9948. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b01195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith P.T., Benke B.P., An L., Kim Y., Kim K., Chang C.J. A Supramolecular Porous Organic Cage Platform Promotes Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution from Water Catalyzed by Cobalt Porphyrins. ChemElectroChem. 2021;8:1653–1657. doi: 10.1002/celc.202100331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lv X., Chen Y., Wu Y., Wang H., Wang X., Wei C., Xiao Z., Yang G., Jiang J. A Br-regulated transition metal active-site anchoring and exposure strategy in biomass derived carbon nanosheets for obtaining robust ORR/HER electrocatalysts at all pH values. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:27089–27098. doi: 10.1039/C9TA10880G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Z., Ozoemena K.I., Maree D.M., Nyokong T. Synthesis and electrochemical studies of a covalently linked cobalt(II) phthalocyanine–cobalt(II) porphyrin conjugate. Dalton Trans. 2005:1241–1248. doi: 10.1039/B418611G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atoguchi T., Aramata A., Kazusaka A., Enyo M. Electrocatalytic activity of CoII TPP-pyridine complex modified carbon electrode for CO2 reduction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1991;318:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(91)85312-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Y.-J., Yu Z.-T., Chen D.-Q., Zou Z.-G. Metal-complex chromophores for solar hydrogen generation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:603–631. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00436A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawrence M.A.W., Celestine M.J., Artis E.T., Joseph L.S., Esquivel D.L., Ledbetter A.J., Cropek D.M., Jarrett W.L., Bayse C.A., Brewer M.I., et al. Computational, electrochemical, and spectroscopic studies of two mononuclear cobaloximes: The influence of an axial pyridine and solvent on the redox behaviour and evidence for pyridine coordination to cobalt(I) and cobalt(II) metal centres. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:10326–10342. doi: 10.1039/C6DT01583B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKone J.R., Marinescu S.C., Brunschwig B.S., Winkler J.J., Gray H.B. Earth-abundant hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:865–878. doi: 10.1039/C3SC51711J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Y., Veleta J.M., Tang D., Price A.D., Botez C.E., Villagrán D. Efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen gas evolution by a cobalt–porphyrin-based crystalline polymer. Dalton Trans. 2018;47:8801–8806. doi: 10.1039/C8DT00302E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Attatsi I.K., Weihua Zhu W., Liang X. Noncovalent immobilization of Co(II)porphyrin through axial coordination as an enhanced electrocatalyst on carbon electrodes for oxygen reduction and evolution. New J. Chem. 2020;44:4340–4345. doi: 10.1039/C9NJ02408E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y.-H., Schneider P.E., Goldsmith Z.K., Mondal B., Hammes-Schiffer S., Stahl S.S. Brønsted Acid Scaling Relationships Enable Control Over Product Selectivity from O2 Reduction with a Mononuclear Cobalt Porphyrin Catalyst. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019;5:1024–1034. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Z.-S., Chen C., Liu J., Parvez K., Liang H., Shu J., Sachdev H., Graf R., Feng X., Müllen K. High-Performance Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Derived from Cobalt Porphyrin-Based Conjugated Mesoporous Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:1450–1455. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pessoa C.A., Gushikem Y. Cobalt porphyrins immobilized on niobium(V) oxide grafted on a silica gel surface: Study of the catalytic reduction of dissolved dioxygen. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines. 2001;5:537–544. doi: 10.1002/jpp.360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biloul A., Gouerec P., Savy M., Scarbeck G., Besse S., Riga J. Oxygen electrocatalysis under fuel cell conditions: Behaviour of cobalt porphyrins and tetraazaannulene analogues. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1996;26:1139–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF00243739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gouerec P., Bilou A., Contamin O., Scarbeck G., Savy M., Barbe J.M., Guilard R. Dioxygen reduction electrocatalysis in acidic media: Effect of peripheral ligand substitution on cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1995;398:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(95)04136-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukhopadhyay S., Basu O., Das S.K. ZIF-8 MOF Encapsulated Co-porphyrin, an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation in a Wide pH Range: Works Better at Neutral pH. ChemCatChem. 2020;12:5430–5438. doi: 10.1002/cctc.202000804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xie J., Xu P., Zhu Y., Wang J., Lee W.-C.C., Zhang X.P. New Catalytic Radical Process Involving 1,4-Hydrogen Atom Abstraction: Asymmetric Construction of Cyclobutanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:11670–11678. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c04968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Q.-J., Mao M.-J., Chen J.-X., Huang Y.-B., Cao R. Integration of metalloporphyrin into cationic covalent triazine frameworks for the synergistically enhanced chemical fixation of CO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020;10:8026–8033. doi: 10.1039/D0CY01636E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C., Lang K., Lu H., Hu Y., Cui X., Wojtas L., Zhang X.P. Catalytic Radical Process for Enantioselective Amination of C(sp3)–H Bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:16837–16841. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zardi P., Intrieri D., Caselli A., Gallo E. Co(porphyrin)-catalysed amination of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene derivatives by aryl azides. J. Organomet. Chem. 2012;716:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2012.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan T.L., To C.T., Liao B.-S., Liu S.-T., Chan K.S. Electronic Effects of Ligands on the Cobalt(II)–Porphyrin-Catalyzed Direct C–H Arylation of Benzene. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012;2012:485–489. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201100780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin X.Q., Boisselier-Cocolios B., Kadish K.M. Electrochemistry, Spectroelectrochemistry, and Ligand Addition Reactions of an Easily Reducible Cobalt Porphyrin. Reactions of Tetracyanotetraphenylporphinato)cobalt(II) ((CN)4TPP)CoII) in Pyridine and in Pyridine/Methylene Chloride Mixtures. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:3242–3248. doi: 10.1021/ic00238a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kadish K.M. The Electrochemistry of Metalloporphyrins in Nonaqueous Media. In: Lippard S.J., editor. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry. Volume 34. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 1986. pp. 345–605. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Connelly N.G., Geiger W.E. Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:877–910. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Long C., Wan K., Qiu X., Zhang X., Han J., An P., Yang Z., Li X., Guo J., Shi X., et al. Single site catalyst with enzyme-mimic micro-environment for electroreduction of CO2. Nano Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12274-021-3756-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Du P., Eisenberg R. Catalysts made of earth-abundant elements (Co, Ni, Fe) for water splitting: Recent progress and future challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:6012–6021. doi: 10.1039/c2ee03250c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Artero V., Chavarot-Kerlidou M., Fontecave M. Splitting water with cobalt. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7238–7266. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zee D.Z., Chantarojsiri T., Long J.R., Chang C.J. Metal polypyridyl catalysts for electro- and photochemical reduction of water to hydrogen. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:2027–2036. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pal R., Laureanti J.A., Groy T.L., Jones A.K., Trovitch R.J. Hydrogen production from water using a bis(imino)pyridine molybdenum electrocatalyst. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11555–11558. doi: 10.1039/C6CC04946J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roubelakis M.M., Bediako D.K., Dogutan D.K., Nocera D.G. Proton-coupled electron transfer kinetics for the hydrogen evolution reaction of hangman porphyrins. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:7737–7740. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21123h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kellett R.M., Spiro T.G. Cobalt(I) porphyrin catalysts of hydrogen production from water. Inorg. Chem. 1985;24:2373–2377. doi: 10.1021/ic00209a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brahmi J., Nasri S., Briki C., Guergueb M., Najmudin S., Aouadi K., Sanderson M.R., Winter M., Cruickshank D., Nasri H. X-ray molecular structure characterization of a hexamethylenetetramine zinc(II) porphyrin complex, catalytic degradation of toluidine blue dye, experimental and statistical studies of adsorption isotherms. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;341:117394. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soury R., Jabli M., Saleh T.A., Abdul-Hassan W.S., Saint-Aman E., Loiseau F., Philouze F., Bujacz A., Nasri H. Synthesis of the (4,4′-bipyridine)(5,10,15,20-tetratolylphenylporphyrinato)zinc(II) bis(4,4-bipyridine) disolvate dehydrate and evaluation of its interaction with organic dyes. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;264:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.05.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simonova O.R., Zdanovich S.A., Zaitseva S.V., Koifman O.I. Kinetic Study of the Redox Properties of [5,10,15,20-Tetrakis(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)porphyrinato]cobalt(II) in the Reaction with Hydrogen Peroxide. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020;90:863–869. doi: 10.1134/S1070363220050175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eaton S.S., Boymel P.M., Sawant B.M., More J.K., Eaton G.R. Metal-Nitroxyl Interactions. 32. Spin-Spin Splitting in EPR Spectra of Spin-Labeled Pyridine Adducts of a Cobalt(II) Porphyrin in Frozen Solution. J. Magnet. Res. 1984;56:183–199. doi: 10.1016/0022-2364(84)90097-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.More K.M., Eaton G.R., Eaton S.S., Hankovszky O.H., Hideg K. Metal-Nitroxyl Interactions. 53. Effect of the Metal-Nitroxyl Linkage on the Electron-Electron Exchange Interaction in Spin-Labeled Complexes of Copper(II), Low-Spin Cobalt(II), Vanadyl, and Chromium(III) Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:1734–1743. doi: 10.1021/ic00308a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adler A.D., Longo F.R., Finarelli J.D., Goldmacher J., Assour J., Korsakoff L. A Simplified Synthesis for meso-Tetraphenylporphin. J. Org. Chem. 1967;32:476. doi: 10.1021/jo01288a053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adler A.D., Longo F.R., Kampas F., Kim J. On the preparation of metalloporphyrins. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970;32:2445–2448. doi: 10.1016/0022-1902(70)80535-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mansour A., Belghith Y., Belkhiria M.S., Bujacz A., Guérineau V., Nasri H. Synthesis, crystal structures and spectroscopic characterization of Co(II) bis(4,4′-bipyridine) with mesoporphyrins α,β,α,β-tetrakis(o-pivalamidophenyl) porphyrin (α,β,α,β-TpivPP) and tetraphenylporphyrin (TPP) J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines. 2013;17:1094–1103. doi: 10.1142/S1088424613500843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Francis S., Rajith L. Selective Fluorescent Sensing of Adenine Via the Emissive Enhancement of a Simple Cobalt Porphyrin. J. Fluoresc. 2021;31:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s10895-021-02685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rathi P., Butcher R., Sankar M. Unsymmetrical nonplanar ‘push–pull’ β-octasubstituted porphyrins: Facile synthesis, structural, photophysical and electrochemical redox properties. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:15002–15011. doi: 10.1039/C9DT02792K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kobayashi H., Kaizu Y. Photodynamics and Electronic Structures of Metal Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1985;64:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0010-8545(85)80041-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Antipas A., Gouterman M. Porphyrins. 44. Electronic States of Co, Ni, Rh, and Pd Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:4896–4901. doi: 10.1021/ja00353a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guo X., Guo B., Shi T. The photochemical and electrochemical properties of chiral porphyrin dimer and self-aggregate nanorods of cobalt(II) porphyrin dimer. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2010;363:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2009.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pu G., Yang Z., Wu Y., Wang Z., Deng Y., Gao Y.J., Zhang Z., Lu X. Investigation into the Oxygen-Involved Electrochemiluminescence of Porphyrins and Its Regulation by Peripheral Substituents/Central Metals. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:2319–2328. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kadish K.M., Li J., Van Caemelbecke E., Ou Z., Guo N., Autret M., D’Souza F., Tagliatesta P. Electrooxidation of Cobalt(II) α-Brominated-Pyrrole Tetraphenylporphyrins in CH2Cl2 under an N2 or a CO Atmosphere. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:6292–6298. doi: 10.1021/ic970789n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.D’Souza F., Villard A., Caemelbecke E., Franzen M., Boschi T., Tagliatesta P., Kadish K.M. Electrochemical and Spectroelectrochemical Behavior of Cobalt(III), Cobalt(II), and Cobalt(I) Complexes of meso-tetraphenylporphyrinate Bearing Bromides on the β-Pyrrole Positions. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:4042–4048. doi: 10.1021/ic00071a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ke X., Yadav P., Cong L., Kumar R., Sankar M., Kadish K.M. Facile and Reversible Electrogeneration of Porphyrin Trianions and Tetraanions in Nonaqueous Media. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:8527–8537. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hu X.M., Rønne M.H., Pedersen S.U., Skrydstrup T., Daasbjerg K. Enhanced Catalytic Activity of Cobalt Porphyrin in CO2 Electroreduction Upon Immobilization on Carbon Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:1–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Behar D., Dhanasekaran T., Neta P., Hosten C.M., Ejeh D., Hambright P., Fujita E. Cobalt Porphyrin Catalyzed Reduction of CO2, Radiation Chemical, Photochemical, and Electrochemical Studies. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:2870–2877. doi: 10.1021/jp9807017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Perrin D.D., Armarego W.L.F. Purification of Organic Solvents. Pergamon Press; Oxford, UK: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Denden Z., Ezzayani K., Saint-Aman E., Loiseau F., Najmudin S., Bonifácio C., Daran J.C., Nasri H. Insights on the UV/Vis, Fluorescence, and Cyclic Voltammetry Properties and the Molecular Structures of ZnII Tetraphenylporphyrin Complexes with Pseudohalide Axial Azido, Cyanato-N, Thiocyanato-N, and Cyanido Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015;2015:2596–2610. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201403214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ezzayani K., Denden Z., Najmudin S., Bonifácio C., Saint-Aman E., Loiseau F., Nasri H. Exploring the Effects of Axial Pseudohalide Ligands on the Photophysical and Cyclic Voltammetry Properties and Molecular Structures of MgII Tetraphenyl/porphyrin Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014;2014:5348–5361. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201402546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.