Short abstract

Content available: Audio Recording

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- CENATRA

Centro Nacional de Trasplantes

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- LT

liver transplantation

- MAFLD

metabolic‐associated fatty liver disease

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- UMAE

Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad

Listen to an audio presentation of this article.

Cirrhosis is the final stage of various chronic liver diseases and is a public health threat, accounting for more than 1 million deaths worldwide. In Mexico, liver‐related diseases constitute the sixth most common cause of death in the economically active population. 1 Despite the high burden on global health systems, cirrhosis continues to be neglected by most sectors of the population. Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) remains the only effective therapeutic option for patients with advanced disease.

History of Liver Transplantation in Mexico

The history of liver transplantation (LT) in Mexico started in 1976, one decade after Dr. Thomas Starzl performed the first successful LT in the world. Motivated by the promising results in other countries, Dr. Hector Orozco‐Zepeda and his team attempted the first LT in Mexico on a 44‐year‐old woman diagnosed with cirrhosis. Unfortunately, the patient died in the postoperative period. This led Dr. Orozco‐Zepeda and Dr. Hector Diliz to pursue further training under the guidance of Dr. Starzl in the United States. On their return, Orozco‐Zepeda and Diliz began an experimental surgery program on dogs at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” in Mexico City. It took them 1 year to master the procedure. In March 1985, they performed the first successful OLT in Mexico. 2 By the end of 1990, the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” had conducted the first 11 OLTs in Mexico. 3

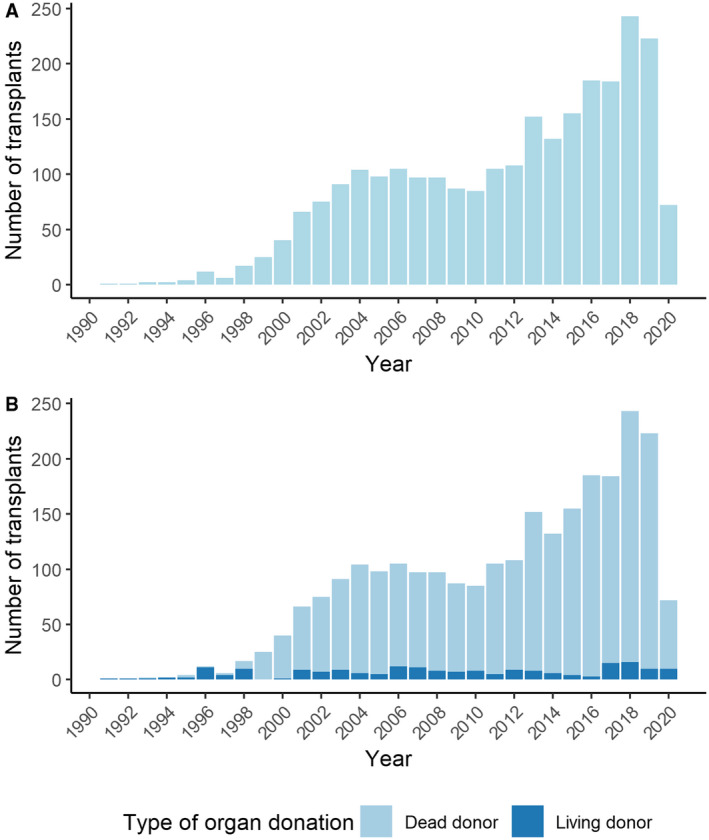

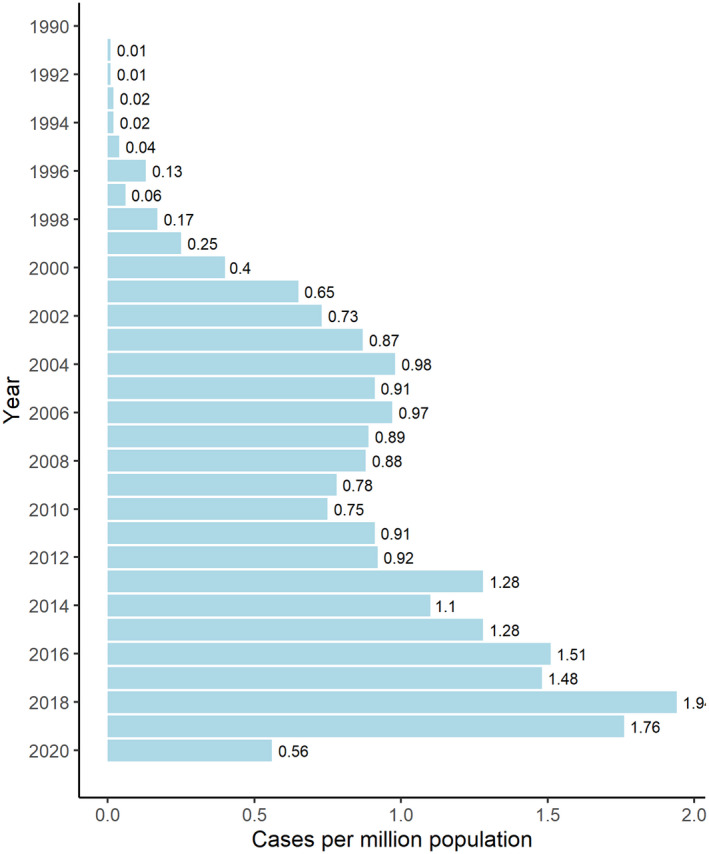

The initial success sparked interest in OLT as a viable treatment for liver diseases. During the 1990s, the Mexican government started to develop laws for transplant regulation, culminating with the creation of the Centro Nacional de Trasplantes (CENATRA) in 1999, the regulating agency that coordinates organ donation and transplantation activities in both public and private sectors of Mexico. Over the next two decades, the number of OLTs performed in Mexico per year increased from 25 in 1999 to 223 in 2019 (Fig. 1). To date, a total of 2585 OLTs have been performed in Mexico, 2384 from deceased donors and 201 from living donors. All living donor OLTs were in pediatric patients. Even though the incidence of end‐stage liver disease is increasing in the Mexican population, Mexico’s LT rate per million population remains one of the lowest in the Americas (Table 1 and Fig. 2). 4 , 5 , 6

FIG 1.

Number of LTs per year in Mexico from 1991 to 2020.

TABLE 1.

LT Rates Across Different Countries in the Americas Region

| Country | LT Annual Rate (Per Million Population) |

|---|---|

| United States | 109.9 |

| Canada | 78.1 |

| Argentina | 10.8 |

| Brazil | 10.4 |

| Chile | 9.1 |

| Uruguay | 7.0 |

| Colombia | 5.0 |

| Costa Rica | 3.9 |

| Ecuador | 1.8 |

| Mexico | 1.8 |

| Peru | 1.6 |

| Bolivia | 0.3 |

| Paraguay | 0.3 |

FIG 2.

Cases of LTs per million habitants in Mexico from 1991 to 2020.

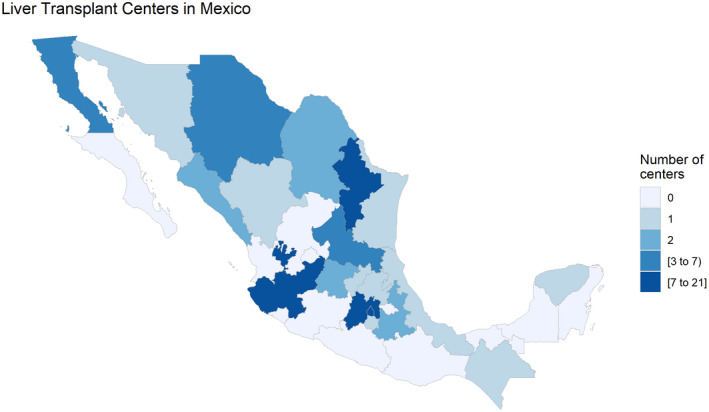

Since its creation to date, CENATRA has approved 84 centers in Mexico for LT (Fig. 3), most of them belonging to the private sector. Despite the relatively high number of centers, only 23 remain active, 7 performed at least 10 transplants per year, and 22 are located in Mexico City. 4 This restricts transplantation procedures to very few locations and jeopardizes the quality of the procedures performed at many centers. Unfortunately, the follow‐up outcomes for most patients undergoing OLT in Mexico remain unknown. The only center that reports these data has 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year survival rates of 94%, 88%, and 88%, respectively. 7

FIG 3.

Distribution of LT centers by state in Mexico.

Changes in the Cause of Cirrhosis in the Last Few Decades

The advent of direct‐acting antivirals and the growing obesity epidemic have shifted the causes of cirrhosis, predominantly in high‐income countries (Europe and the United States). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) moved from being the leading cause of cirrhosis worldwide to a curable infection nowadays; cases of cirrhosis secondary to HCV are on the decline. In contrast, metabolic‐associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease now constitute the leading causes of cirrhosis in western countries. The MAFLD spectrum varies from the slowly progressive fatty liver disease to the aggressive nonalcohol steatohepatitis, which carries a significant risk for progression to cirrhosis. 8 , 9

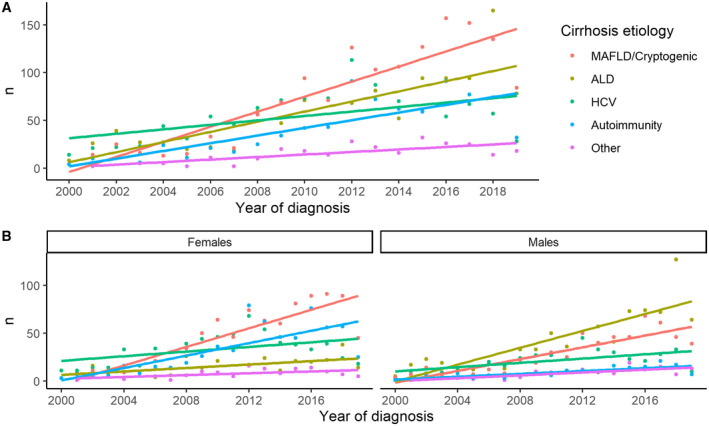

According to data reported by the LT program at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán,” the most active transplant center in Mexico, among the 115 LTs performed between 1976 and 2012, HCV was the main cause of cirrhosis, followed by autoimmune liver disease and MAFLD. 7 Since then, the prevalences of obesity and metabolic syndrome, which are diagnostic criteria for MAFLD, have increased significantly in Mexico. Recently, a study that collected data from five reference centers in Mexico City with more than 4500 Mexican patients with cirrhosis revealed that, like western countries, MAFLD is now the main cause of cirrhosis, followed by alcoholic liver disease and HCV (Fig. 4). 10 It is likely that the burden of MAFLD will continue to increase in Mexico and all over the globe.

FIG 4.

Changing trends in the cause of liver disease in Mexico from 2000 to 2019. (A) Overall. (B) By gender. Reproduced with permission from Hepatology.10 Copyright 2020, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

CURRENT AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

One of Mexico’s most critical challenges is cirrhosis detection. Due to the lack of screening programs, many patients remain undiagnosed. Developing appropriate detection programs will increase the number of admissions to the CENATRA’s LT waiting list.

Another potential short‐term solution might be to reduce the number of active transplant centers and turn them into reference centers for LT. Because only a few centers perform more than 10 OLTs per year (Table 2), it seems plausible to increase and relocate resources to 50% of the current active centers distributed throughout the country to improve the number of transplants per year. Following this plan, Mexico might double the number of OLTs per year and should demand these centers achieve survival rates at 1, 3, and 10 years similar to those reported in high‐income countries. 11

TABLE 2.

Transplant Centers That Perform More Than 10 OLTs per Year (Until 2019)

| Center | Transplant Hospital | Number of OLTs per Year | State |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” | 49 | Mexico City |

| 2 | Centro Médico Nacional “20 de Noviembre” | 26 | Mexico City |

| 3 | UMAE Hospital de Especialidades No. 25 | 16 | Mexico City |

| 4 | Unidad de Alta Especialidad “Doctor Gaudencio González Garza” C.M.N. “La Raza” | 14 | Nuevo León |

| 5 | Operadora de Hospitales Ángeles S.A de C.V | 13 | Jalisco |

| 6 | U.M.A.E. Hospital de Especialidades "Dr. Antonio Fraga Mouret" C.M.N. “La Raza” | 11 | Mexico City |

| 7 | Operadora De Hospitales Angeles S.A de C.V. | 11 | Mexico City |

Improving the regulation of transplant centers will increase their experience over time. This will grant the opportunity to increase indications for LT, such as acute alcoholic hepatitis in well‐selected cases, and to increase the availability of organs for transplantation, such as the use of HCV‐positive donors with negative receptors (because of universal access to direct‐acting antivirals) or the possibility of using donors with extended criteria. 12

In conclusion, Mexico’s LT programs have come a long way. However, despite significant progress being made, there is still room for improvement. The main challenges ahead are increasing cirrhosis detection, increasing wait‐list admissions, and adequately regulating transplant centers. To complicate things further, the ever‐growing threat of MAFLD might increase the number of patients who require LT in the future. Addressing these issues will benefit all parties involved.

References

- 1. INEGI . Características de las Defunciones Registradas en México Durante Enero a Agosto de 2020. Available at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2021/EstSociodemo/DefuncionesRegistradas2020_Pnles.pdf. Published January 27, 2021. Accessed April 23, 2021.

- 2. Orozco‐Zepeda H. Un poco de historia sobre el trasplante hepático. Rev Investig Clin 2005;57:124‐128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan C, Olivera MA, Leal R, et al. Programa de Trasplante Hepático en el Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2003;68:8386. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centro Nacional de Trasplantes . CENATRA. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/cenatra. Accessed May 15, 2021.

- 5. Contreras AG, McCormack L, Andraus W, et al. Current status of liver transplantation in Latin America. Int J Surg 2020;82:14‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. 57th Directing Council of the 71st Session of the Regional Commitee of WHO for the Americas . Strategy and Plan of Action on Donation and Equitable Access to Organ, Tissue, and Cell Transplants 2019‐2030. Available at: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/51619/CD57‐11‐e.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Published August 19, 2019. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- 7. Vilatobá M, Mercado MÁ, Contreras‐Saldivar AG, et al. Liver transplant center in México with low‐volume and excellent results. Gac Mexico 2017;153:405‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haldar D, Kern B, Hodson J, et al. Outcomes of liver transplantation for non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis: a European Liver Transplant Registry study. J Hepatol 2019;71:313‐322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Ong J, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly increasing indication for liver transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:580‐589.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonzalez‐Chagolla A, Olivas‐Martínez A, Valenzuela‐Vidales AK, et al. Changing trends in etiology‐based chronic liver disease from 2000 through 2019 in Mexico: multicenter study. Hepatology 2020;72:383A‐384A. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burra P, Burroughs A, Graziadei I, et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines: liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2016;64:433‐485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pérez IB, Duca A. Top papers in liver transplantation 2017‐2018. Transplant Proc 2021;53:620‐623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]