Abstract

Neutrophils, the most abundant circulating leukocyte, are critical for host defense. Granulopoiesis is under the control of transcriptional factors and culminates in mature neutrophils with a broad armamentarium of antimicrobial pathways. These pathways include NADPH oxidase, which generates microbicidal reactive oxidants, and non-oxidant pathways that target microbes through several mechanisms. Activated neutrophils can cause or worsen tissue injury, underscoring the need for calibration of activation and resolution of inflammation when infection has been cleared. Acquired neutrophil disorders are typically caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents. Primary neutrophil disorders typically result from disabling mutations of individual genes that result in impaired neutrophil number or function, and provide insight into basic mechanisms of neutrophil biology. Neutrophils can also be activated by non-infectious causes, including trauma and cellular injury, and can have off-target effects in which pathways that typically defend against infection exacerbate injury and disease. These off-target effects include acute organ injury, autoimmunity, and variable effects on the tumor microenvironment that can limit or worsen tumor progression. A greater understanding of neutrophil plasticity in these conditions is likely to pave the way to new therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular traps, granulopoiesis, innate immunity, phagocytosis, degranulation, neutrophil dysfunction

Capsule Summary

Neutrophils mediate pathogen defense and inflammation through multiple mechanisms. We provide a discussion of the current understanding of neutrophil biology, host defense mechanisms, and the role of neutrophils in inflammatory, autoimmune and malignant diseases.

Introduction

Neutrophils are the most plentiful leukocyte type found in human peripheral blood, constituting about 60% of white blood cells in human blood. They are a major cellular contributor to inflammation, mediating the early phases of inflammatory responses. They can eliminate microbes via multiple mechanisms, and are critical for host defense. However, the same pathways that kill pathogens and amplify inflammation can also cause injury to the host. Therefore, calibration of neutrophil responses to defend against pathogens while averting excessive tissue injury is required.

The following are key requirements for neutrophil-mediated host defense: (i) adequate number of circulating neutrophils; (ii) trafficking to sites of infection and injury; (iii) sensing of microbes; phagocytosis; (iv) killing of pathogens (or containing infection); and termination of inflammation after pathogen clearance. Impairment of these pathways can result from a number of causes, including disabling mutations in critical genes and acquired immunodeficiencies (e.g., bone marrow disorders and immunosuppressive therapy). This review will focus on normal neutrophil biology and diseases associated with neutrophil dysfunction.

Neutrophil Development

In the bone marrow, multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs) differentiate into common myeloid progenitor cells (CMPs). Granulopoiesis is regulated by specific transcriptional factors that are activated at different stages of development. The CMPs generate granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells (GMPs). These GMPs, when exposed to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), differentiate into myeloblasts, committing to neutrophil generation. Neutrophils arise from myeloblasts over about a 14 day period1. First the myeloblast differentiates into a promyelocyte, followed by a myelocyte, both of which have a round nucleus. At the metamyelocyte stage, the nucleus changes into a kidney shape. Metamyelocytes mature to band cells with a band-shaped nucleus, and finally these mature into mature neutrophils (polymorphonuclear granulocytes), with their classic segmented nucleus.

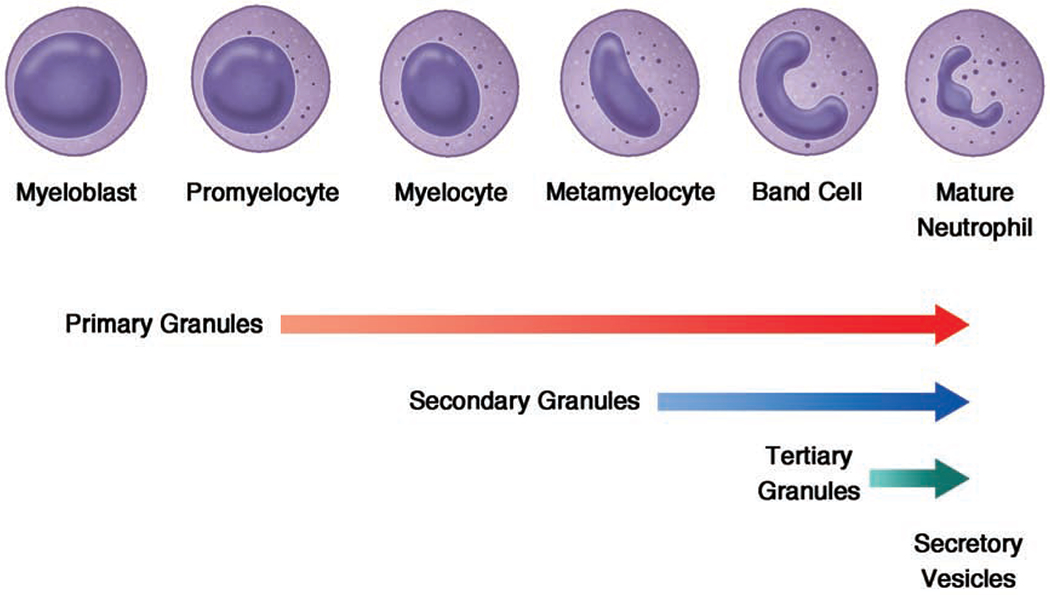

Neutrophil granule formation occurs progressively throughout the different stages of neutrophil maturation. Primary (azurophilic) granules are found at the myeloblast to promyelocyte stage. Secondary (specific) granules are first observed at myelocyte and metamyelocyte stages. Tertiary (gelatinase) granules are not found until the band cell stage. Finally, secretory vesicles are seen only in mature neutrophils2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Neutrophil development and granule formation. Myeloblasts are the first committed precursor cells of the neutrophil lineage. These differentiate into promyelocytes followed by myelocytes. These cells then proceed through maturation steps of metamyelocytes, band cells, and mature segmented neutrophils. As neutrophils mature, they develop granules which play a key role in neutrophil microbicidal activity. Primary (azurophilic) granules develop as neutrophils are differentiating from myeloblasts to promyelocytes. Secondary (specific) granules form in myelocytes and metamyelocytes. Tertiary (gelatinase) granules first appear in band cells. Secretory vesicles are small, easily exocytosed organelles, which are present only in mature, segmented neutrophils.

During neutrophil maturation, integrin α4β1 (VLA4) and chemokine receptor CXCR4 are downregulated, while CXCR2 and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) are upregulated. The bone marrow stromal cells express vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), a ligand for VLA4, and CXCL12, a ligand for CXCR4, to retain myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow. G-CSF downregulates CXCR4 on neutrophils and its ligand CXCL12 on bone marrow stromal cells, allowing mature neutrophils to leave the bone marrow and enter the peripheral circulation, mediated by interactions of CXCR2 with CXCL1 and CXCL23.

Neutrophil Biology

Neutrophils are granular, large leukocytes (about 12-15um in diameter) with a nucleus that is segmented into three to five lobules. Human neutrophils are abundant, with adult humans producing over 1 x1011 neutrophils per day4. They have been conventionally considered a very short-lived cell in the peripheral blood, with a half-life in circulation of approximately 6-8 hours5. This concept has been challenged in a study using in vivo stable isotope labeling with heavy water (2H2O)that estimated the in vivo half-life of circulating neutrophils is much longer, about 3.7 days6. However, a more recent study also using 2H2O labeling as well as deuterium-labeled glucose support older concepts of a shorter half-life on the magnitude of hours rather than days7. Neutrophils express a large number of selectins, chemokine receptors, and integrins that allow them to be rapidly recruited from the circulation to a site of tissue injury or infection. Once activated in tissues, neutrophils mediate host defense via multiple mechanisms including phagocytosis of pathogens, production of antimicrobial and proinflammatory enzymes, oxidative burst to generate toxic reactive oxygen species, and release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) into the extracellular space. Like many immune cell types, neutrophils display circadian rhythmic variations in many of these key functions, including adhesion molecule and chemokine receptor expression, superoxide production, and phagocytic activity,8–10 though the relative expression of circadian clock genes may be lower in neutrophils than other immune cell types8.

Pathogen recognition and phagocytosis

Human neutrophils express a wide variety of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including Toll-like receptors TLR1 through TLR10 (with the exception of TLR3 and TLR7), C-type lectin receptors (e.g., Dectin-1), Nod-like receptors, and others, enabling them to initiate various important immune responses upon recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)11. In neutrophils, phagocytosis may be initiated by PRR-PAMP interaction, but more effective phagocytosis is mediated via neutrophil Fcγ receptors or complement receptor 3 (CR3; CD11b/CD18; Mac-1) receptors binding to IgG- or C3bi-opsonized microbes, respectively. CR3 plays a dual role in complement-mediated phagocytosis of microbes and neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells required for trafficking. Activation of neutrophils by pathogens and other stimuli increases surface expression of CR3, thereby amplifying the capacity of neutrophils to phagocytose pathogens and to traffic to sites of infection.

Pathogens are engulfed into a cell membrane-derived vacuole called the phagosome. Phagosomal maturation occurs via the fusion of the phagosome with secretory vesicles and granules, to acquire antimicrobial enzymes and components of the NADPH oxidase complex12. Additionally, PRR activation initiates the process of neutrophil degranulation, releasing the proinflammatory contents of neutrophil primary, secondary, tertiary and secretory granules (discussed below). Fusion of secondary granules with the plasma membrane results in increased surface expression of cytochrome b558 (p22phox and gp91phox heterodimer), a component of the NADPH oxidase complex, which enhances extracellular reactive oxidant generation (discussed below).

Neutrophil Granules

Three types of neutrophil granules are present in mature neutrophils, and these granules are all filled with pro-inflammatory contents (Table I). The function of these preformed neutrophil granular constituents is to rapidly respond to infectious threats by activation of multiple host defense pathways. Primary granules are also called azurophilic granules and their major protein content is myeloperoxidase (MPO). Because of this, they have also been termed peroxidase-positive granules. Primary granules also contain defensins, serine proteases, proteinase 3, cathepsin G and C, bactericidal permeability-increasing protein (BPI), neutrophil elastase, CAP37 (azurocidin), and NSP4. Secondary granules, also called specific granules, contain lactoferrin, hCAP-18 (cathelicidin), collagenase (MMP8), β2-microglobulin, haptoglobin, pentraxin-3, NGAL and SLPI. In the unstimulated neutrophil, cytochrome b558 is principally expressed in secondary granules. Tertiary granules contain gelatinase (MMP9), arginase I, and ficolin I. The presence of gelatinase, and absence of lactoferrin or NGAL distinguishes tertiary granules from secondary granules, both of which are peroxidase-negative. MMP9 likely plays a role in neutrophil-mediated remodeling of extracellular matrix enabling neutrophils to migrate to sites of infection within tissue following extravasation, while the arginase pathway likely plays a role in wound healing. Nearly all proteins in primary granules are proteolytically processed prior to storage in the granules. In contrast, proteins in secondary and tertiary granules are stored unprocessed and inactive13.

Table I:

Neutrophil Granule Contents

| Primary (Azurophilic) Granules | Secondary (Specific) Granules | Tertiary Granules |

|---|---|---|

| Myeloperoxidase | Lactoferrin | MMP9 |

| Neutrophil elastase | Cathelicidin | Arginase I |

| Cathepsin G and C | MMP8 | Ficolin I |

| Proteinase 3 | β2-microglobulin | Cytochrome b558 |

| Defensins | Haptoglobin | |

| CAP37 | Pentraxin-3 | |

| NSP4 | NGAL | |

| BPI | SLP | |

| Properdin | ||

| Cytochrome b558 (membrane-bound component of NADPH oxidase) |

Some of proteins are expressed in more than one granule subset. For example, lysozyme is expressed in primary, secondary, and tertiary granules.

Neutrophil Oxidative Burst

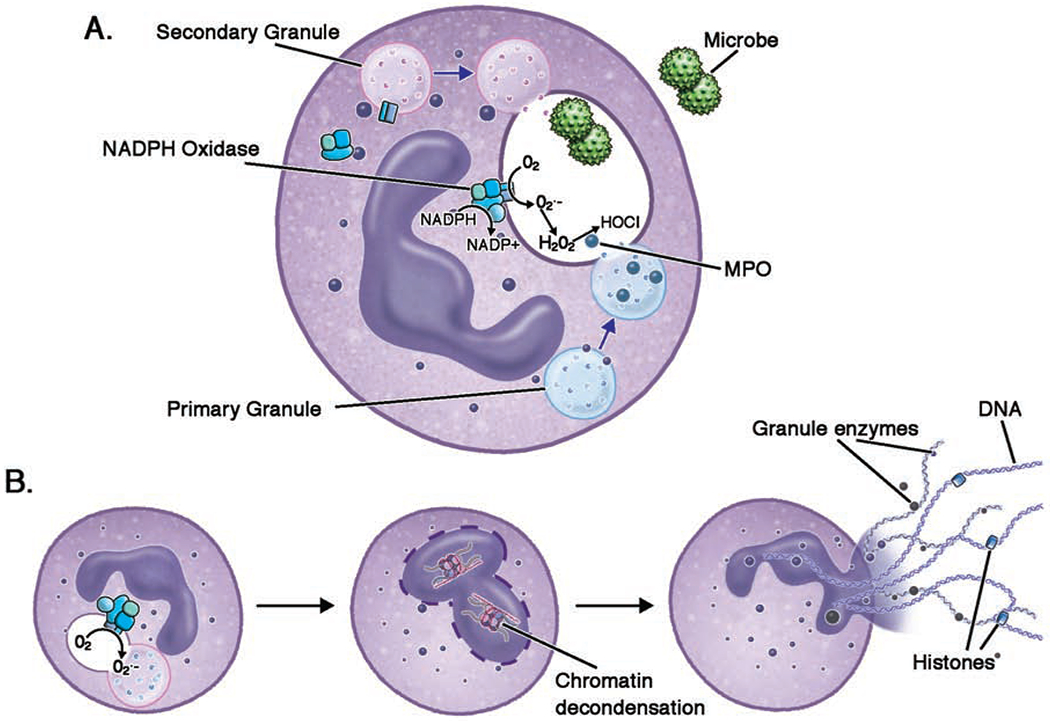

In neutrophils, the activated NADPH oxidase converts oxygen into reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidizing products that can kill microbes. The NADPH oxidase complex is comprised of a membrane-bound heterodimer, gp91phox (CYBB or NOX2) and p22phox (CYBA), and 3 cytosolic subunits, p47phox (NCF1), p67phox (NCF2), and p40phox (NCF4). Upon activation, the cytosolic subunits assemble upon the scaffold of the membrane-bound portion to make a functional, 5-subunit oxidase complex. Complex assembly can occur at the plasma membrane, or at the phagosomal membrane during ingestion of particles. The small GTP-binding protein Rac2 dissociates from its inhibitor GDI and binds GTP, joining with the complex to enhance oxidase activation and superoxide formation14. The NADPH oxidase transfers one electron from cytosolic NADPH to molecular oxygen. The product of this reaction, superoxide anion (O2•−), is then converted to other reactive oxygen metabolites, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). H2O2 can combine with chloride to form hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a potent antimicrobial, in a reaction catalyzed by myeloperoxidase (MPO)15 (Figure 2a). Hydroxyl anion (OH−) can be generated from superoxide anion via the iron-dependent Fenton reaction. In addition, reactive oxidant and nitrogen intermediates can react to generate microbicidal radicals, e.g. peroxynitrite anion. In addition to the direct antimicrobial effects of NADPH oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of NADPH oxidase can amplify host defense through other pathways. In neutrophils, NADPH oxidase activation can result in solubilization and activation of granular proteases that mediate host defense 16 and in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps (described below).

Figure 2:

Neutrophil microbicidal activities; a.) Following phagocytosis of microbes, fusion of neutrophil granules with the phagosome introduces antimicrobial granule contents into the phagosome. Non-azurophilic granules transport the membrane bound components of the NADPH oxidase into the phagosome, where they assemble with cytoplasmic components. The assembled NADPH oxidase transfers an electron from cytosolic NADPH to oxygen, forming O2−. O2− is converted into H2O2, and MPO combines H2O2 with Cl to form HOCl. b.) NETs are large, extracellular webs of microbicidal cytosolic and granule proteins assembled on a scaffold of decondensed chromatin or mitochondrial DNA (not shown). NET formation may be initiated by a variety of pathogenic triggers. In classic NADPH oxidase-dependent NETotic cell death, ROS trigger MPO to activate and translocate of NE from azurophilic granules to the nucleus, where NE disrupts chromatin packaging. MPO also works synergistically with NE in decondensing chromatin. Two nuclear enzymes are important in chromatin decondensation; DEK, a DNA-binding protein, and PAD4, which citrullinates histone arginine residues.

(H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; HOCl: hypochlorous acid; MPO: myeloperoxidase; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NE: neutrophil elastase; NET: neutrophil extracellular trap; O2•−: superoxide; PAD4: protein-arginine deiminase type 4; ROS: reactive oxygen species)

Finally, NADPH oxidase activation is not only injurious to pathogens, but can also injure host cells; therefore, termination of NADPH oxidase activation and induction of cytoprotective pathways that limit neutrophilic injury are required for host protection 17. As an example, nuclear erythroid-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcriptional factor that is activated by ROS and electrophiles, and induces the activation of numerous ROS-scavenging pathways that limit oxidative stress and cellular injury 18–20.

Neutrophil Extracellular Traps

Upon activation, neutrophils can generate neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)21. NETs are web-like extracellular structures of DNA covered with histones and enzymes such as neutrophil elastase (NE) and myeloperoxidase (MPO), and can be abundant at inflammatory sites. NET generation can be achieved through a cell-death process called NETotic cell death22, which is distinct from apoptosis or necrosis. Alternatively NET formation can occur in living cells when mitochondrial DNA is used as the NET scaffolding23. NETs bind bacteria, fungi and other microbes, providing a high local concentration of antimicrobial molecules to kill pathogens and a barrier to prevent their dissemination24,25. However the strongly alkaline histones and degradative enzymes contained in NETs also have a high cytotoxic potential, and may contribute to host cell death and chronic tissue injury. NET formation can be stimulated by a variety of signals, among them microbial products such as LPS and fungal elements, and by non-infectious triggers including immune complexes and urate crystals26. To initiate NETotic cell death, neutrophils arrest their movement and depolarize. The nuclear envelope then breaks apart and nuclear chromatin is released into the cytoplasm.

NET generation can occur through NADPH oxidase-dependent and –independent pathways 27. ROS generated by NADPH oxidase can trigger MPO to translocate neutrophil elastase (NE) from the primary granules to the cytoplasm28,29. MPO and NE together facilitate decondensation of chromatin, and the chromatin mixes in the cytoplasm with cytoplasmic and granular proteins30. Two other proteins shown to aide in the chromatin decondensation process are DEK31 and peptidylarginine deiminase-4 (PAD4)32, an enzyme that citrullinates arginine residues on histones. The cell membrane finally permeabilizes and the NETs extrude into the extracellular space, a process resulting in neutrophil death (Figure 2b). Depending on the stimulus of NET development, NET formation can be independent of PAD4, NE, MPO, and ROS33–36. ROS also appears to be required for mitochondrial DNA release for NET formation in live cells, driving a reversible actin and tubulin glutathionylation and cytoskeletal rearrangement essential for mitochondrial-sourced NET extrusion37.

Neutrophil Dysfunction

Neutrophils are the primary mediators of innate immunity targeting bacterial and fungal pathogens. They function by phagocytosing pathogens, generating toxic superoxide and its metabolites, releasing antimicrobial peptides, and forming neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). They also recruit additional immune cells to fight infection via the release of cytokines and chemokines. Neutrophil disorders should be considered in patients with recurrent or severe bacterial or invasive fungal infections. Immune deficiencies involving neutrophils may be divided into quantitative and qualitative disorders.

Quantitative Neutrophil Defects

Quantitative neutrophil disorders include drug-induced, autoimmune, and genetic neutropenias. Multiple genetic defects may lead to a phenotype of severe congenital neutropenia (SCN; also referred to as Kostmann disease), characterized by severe chronic peripheral blood neutropenia, defined as counts <200 neutrophils/μL, with maturational arrest of granulocyte precursors at the promyelocyte or myelocyte stage. Patients with SCN develop severe infections in the first several months of life, including omphalitis, skin infections, pneumonia, deep-seated abscesses, and sepsis. In addition to infections, a significant percentage of patients with SCN develop myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia, caused by somatic mutations in CSF3R and RUNX138. Autosomal dominant mutations in ELANE, which encodes for neutrophil elastase, are the cause of the majority of SCN cases in Caucasians39. Autosomal dominant GFI1 mutation may also cause SCN. Activating mutations in the WAS gene cause SCN inherited in an X-linked manner. In this defect, neutropenia is caused by myeloid cell apoptosis related to dysregulated polymerization of the actin cytoskeleton40. Autosomal recessive SCN may be caused by mutations in G6PC341, VPS4542, HAX1, or AK2. A subset of patients with HAX1 deficiency have seizures and developmental delay in addition to severe neutropenia43. AK2 deficiency causes reticular dysgenesis with a phenotype of severe combined immunodeficiency in conjunction with severe neutropenia.

WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome, caused by autosomal dominant gain-of-function CXCR4 mutation, leads to severe neutropenia in conjunction with lymphopenia and monocytopenia, despite the presence of a hypercellular bone marrow. The mutated CXCR4 chemokine receptor is oversensitive to the CXCL12 chemokine, leading mature neutrophils to remain in the bone marrow instead of mobilizing into the peripheral blood44. The CXCR4 antagonist, plerixafor, has shown promise for the treatment of myelokathexis in WHIM syndrome 45,46, and is currently in Phase III clinical trials for this condition47.

Cyclic neutropenia is caused by autosomal dominant mutations in the ELANE gene, at different locations than those causing severe congenital neutropenia. These mutations don’t appear to carry the leukemogenic potential as SCN-causing ELANE mutations48. Children with cyclic neutropenia develop episodes of severe neutropenia typically occurring every 21 days, though ranges between 14-40 days have been reported49. These episodes may become milder with age50. During times of neutropenia, patients develop fever, oral ulcers and bacterial infections. Sepsis, especially with Clostridium spp., has also been reported51. Gingivitis and oral abscesses can cause tooth loss in patients with cyclic neutropenia.

Qualitative Neutrophil Defects

Primary immune deficiencies with qualitative neutrophil defects include those causing defective chemotaxis, impaired neutrophil oxidative function, or defects in neutrophil granules. Defects in the adhesion molecules necessary for neutrophil rolling and firm adhesion along the vascular endothelium and extravasation from the blood stream into infected tissues underlie a group of three disorders termed leukocyte adhesion deficiencies. The most common, LAD1, is still very rare. It is caused by homozygous mutations in ITGB2, the gene which encodes CD18, the common chain of the three β2 integrins on neutrophil surfaces, LFA-1, CR3, and CR4. Neutrophils in LAD1, with low or absent β2 integrin expression, cannot bind to ICAM-1 and -2 on vascular endothelial cells, and are unable to firmly adhere to the endothelial cells or transmigrate into infected tissues52. As CR3 is a complement receptor for iC3b, phagocytosis of complement-coated pathogens is impaired in LAD1 as well53,54. Disease severity correlates inversely with residual CD18 expression53, and the severe phenotype presents with leukocytosis, delayed umbilical cord separation with omphalitis, poor wound healing, periodontitis, and skin, respiratory or gastrointestinal infections with Staphylococcus aureus or gram-negative bacteria, in which pus formation is absent.

LAD2 is a very rare autosomal recessive disease of impaired fucosylation due to mutations in SLC35C1. Fucosylated proteins are absent, including Sialyl-Lewisx, the ligand for selectins on the surface of leukocytes, which prevents tethering and rolling of neutrophils on the vascular endothelium55. The infectious phenotypes of LAD2 is similar to LAD1 though milder, but additional features are present including developmental and growth delay, dysmorphic facies, and the Bombay blood type, caused by a lack of fucosylated antigen H on erythrocytes56. LAD3 is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in FERMT3, which encodes for kindlin-3, required for activation of all β-integrins57. Impaired integrin function on neutrophils leads to severe leukocytosis and recurrent infections, while impaired β3-integrin platelet aggregation causes a bleeding disorder58.

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is caused by defects in NADPH oxidase. Pathologic mutations in any of the 5 genes encoding the subunits of the NADPH oxidase system can result in CGD, but a mutated CYBB (gp91phox) gene, located on the X chromosome, is the most common cause of CGD. While Rac2 also associates with the NADPH oxidase complex, RAC2 mutation actually presents with a clinical phenotype closer to leukocyte adhesion deficiency rather than CGD, given the additional role of Rac2 in mediating chemotaxis and rolling, via its regulation of the actin cytoskeleton59.

Patients with CGD are at increased risk for a subset of catalase-producing pathogens. Major pathogens in CGD include the following, with common manifestations in parentheses: Staphylococcus aureus (severe soft tissue infections, liver abscess, pneumonia) Serratia marcescens (bone infection), Burkholderia cepacia (pneumonia), nocardiosis (pneumonia, central nervous system), and rare bacterial pathogens (e.g., Granulibacter bethesdensis and Chromobacterium violaceum); invasive aspergillosis (pneumonia, dissemination) and other molds are major causes of mortality in CGD 60. The specific spectrum of pathogens to which CGD patients have increased susceptibility points to the requirement for NADPH oxidase in defense against specific pathogens while being dispensable for others.

Catalase appears not to be critical for the virulence of these organisms in hosts with CGD as studies in which the catalase gene was deleted in either Staphylococcus aureus or Aspergillus nidulans did not demonstrate altered virulence in mouse models of CGD61,62. Neutrophils of patients with CGD have variable impairment in their ability to generate ROS ranging from 0.1% to 27.0% of the normal range. Patients with greater residual ROS production typically have less severe disease activity and better survival63.

In contrast to CGD, deficiency in myeloperoxidase (MPO) is very common, yet patients with MPO deficiency are often asymptomatic, without increased frequency of infections. Myeloperoxidase is released from the azurophilic granules into the phagosomes, where it converts hydrogen peroxide to hypohalous acid, killing phagocytosed microbes. However, redundant MPO-independent microbicidal activities make up for lack of MPO in most deficient individuals. Superficial or invasive candidiasis have been reported in patients with MPO deficiency, but the presence of a comorbid immunosuppressive condition such as diabetes mellitus is typically observed 64.

CARD9 is a signaling adaptor protein in phagocytes downstream of the Dectin-1, Dectin-2, Dectin-3, and Minacle fungal-sensing pattern recognition receptors65. Autosomal recessive CARD9 deficiency often presents with candidal meningitis and deep dermatophytosis, in which dermatophytes initially infect the epidermis and nails, but then invade the dermis and disseminate into underlying tissues including bone, lymph nodes and brain66,67. CARD9 deficiency leads to defects in Th17 differentiation through impaired IL-1β and IL-6 production from monocytes68. However, in contrast to other Th17 defects associated with superficial mucocutaneous candidiasis, CARD9-deficient patients exhibit impaired neutrophil recruitment to the CNS in response to fungal infection, and impaired killing of fungi, which appear to contribute to the invasive fungal infections characteristic of the disorder. Neutrophils from CARD9-deficient patients have normal oxidative burst, but have impaired IL-8 release in response to Candida albicans, and have impaired ROS-independent killing of unopsonized Candida spp. through the CR3-Syk-PI3K pathway 68,69. Additionally, CARD9 is essential for microglial production of IL-1β and CXCL1 in response to Candida, which recruit neutrophils to the CNS during candidal infection70.

Neutrophil specific granule deficiency (SGD) is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by C/EBPε mutations71. Neutrophils from patients with SGD have atypical, bilobed nuclei and lack specific/secondary granules and their contents including lactoferrin, transcobalamin I, gelatinase B, and collagenase. They also have decreased defensin proteins in their primary granules. Multiple neutrophil functions are impaired in SGD including neutrophils chemotaxis, receptor upregulation, and oxidative burst. Eosinophils have been shown to be affected in SGD in addition to neutrophils. Patients with SGD develop severe pyogenic infections with bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa72.

Role of Neutrophils in Pathogenesis

Neutrophils in Inflammation/Autoimmunity

Neutrophils have a pathologic role in various inflammatory processes that include acute organ injury, ischemia reperfusion injury, pathologic thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and autoimmunity. Activated neutrophils mediate inflammation by synthesizing and secreting cytokines, chemokines, leukotrienes and prostaglandins. In particular, neutrophils have been shown to synthesize and secrete the chemokine CXCL8, which in turn recruits more neutrophils73. Activated neutrophils also synthesize IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, TGF-β, and TNF-α, which can subsequently activate both neutrophils and other cells of the immune system74. Neutrophils are a significant source of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). LTB4 is a neutrophil chemoattractant, but PGE2 has a mainly anti-inflammatory effect on neutrophils.

It has long been recognized that dysregulated neutrophil activation is an important mediator of inflammation and organ damage in certain autoimmune disorders, with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) being the focus of much study. Recently, a number of studies have also observed that neutrophils are a major source of autoantigens in these diseases75,76 (see discussion below “NETs in autoimmunity”).

Upon migration into RA joints, activated neutrophils encounter aggregates of immunoglobulins. These complexes of immunoglobulins engage Fcγ receptors on the surface of the neutrophil, which attempts to phagocytose the IgG-coated joint tissue, as it would an opsonized microbe. This process, termed “frustrated phagocytosis” then triggers degranulation and production of ROS77. Neutrophil granule contents are implicated in the destruction of the collagen matrix within cartilage78. Oxidative stress as a result of inappropriate release of ROS by neutrophils is implicated in the pathology of RA, causing damage to DNA, and oxidation of lipids, proteins and lipoproteins79.

NETs in tissue injury and thrombosis

NETs have an important role in pathogen defense that include restricting spread of infection and pathogen killing. However, NETs can also lead to injurious effects in the host. In the lungs, NETs can kill epithelial and endothelial cells, with NET histones playing a key role in this NET-mediated cytotoxicity80. NETs have been proposed as a mechanism of airway tissue damage in multiple lung diseases including transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)81 and cystic fibrosis82. Patients with cystic fibrosis often have Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization of their lungs. P. aeruginosa is a strong inducer of NET generation, yet patient-derived isolates of this bacteria are often resistant to killing by NETs83. NET formation is also associated with lung damage in mouse models of acute lung injury from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or P. aeruginosa, and NETs are associated with the development and severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in critically ill patients with pneumonia or sepsis84.

NETs promote occlusion of the vasculature and thrombosis. During thrombosis, the endothelium releases P-selectin which recruits neutrophils and promotes NET extrusion85. Platelet recruitment then occurs and activated platelets can enhance NET formation86. NETs released from the neutrophils provide a scaffold on which the thrombus forms87, and also recruit Factor XIIa, driving the contact pathway of coagulation86. Treatment of mouse models with DNase and PAD4 inhibitor blocks formation of deep vein thrombosis88,89.

NETs in autoimmunity

NETs expose autoantigens such as nucleic acids and proteins in an inflammatory microenvironment that can initiate an autoimmune response in predisposed individuals. The association of increased NET formation and autoimmunity was first described in ANCA-associated vasculitis, but has subsequently been described in anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)76,90–92. Proteins and nucleic acids found in NETs may be the source of key autoantigens, such as MPO, proteinase 3, and dsDNA. In addition to being a potential source for autoantibodies, NET formation in SLE can also be driven by exposure of neutrophils to anti-ribonucleoprotein autoantibodies. NETs have been demonstrated in in vitro and animal models of SLE to drive plasmacytoid dendritic cells to produce high levels type I interferons93,94. IFN-α is an important inflammatory cytokine associated with SLE95, and itself has been shown to promote further NET formation, resulting in a positive-feedback loop93. In SLE, increased NETs are associated with increased disease activity and presence of kidney disease, suggesting that NETs could be a disease activity marker96,97. NET inhibitors have been advancing through studies as therapies for SLE and other autoimmune diseases in which NETs appear to play a role. These investigational drugs include PAD4 inhibitors (in preclinical studies)98,99 and anti-type I IFN monoclonal antibodies100.

Interestingly, while antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine have long been mainstays of SLE treatment, part of their mechanism of action may be the inhibition of autophagy required for NET formation101. Chloroquine inhibits NETs in control and SLE neutrophils in vitro102 as well as in neutrophils in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer103.

Neutrophils in Asthma

Neutrophil infiltration in the lungs of asthmatics has been shown to be associated with asthma severity, and high burden of neutrophils versus eosinophils has been observed in the autopsy lung tissue of patients with fatal asthma104. Neutrophilic asthma has been classified as a specific asthma phenotype, associated with severe disease and steroid-refractoriness. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is also characterized by high sputum neutrophils, and there is felt to be some overlap between neutrophilic asthma and COPD. It has been proposed that the pathophysiology of neutrophilic asthma may be related to a dysbiosis in the lung microbiome, where normal flora is replaced by Tropheryma whipplei and Haemophilus influenzae, with neutrophilia representing the host response to these infections105. However, neutrophilic infiltration in uncontrolled asthma has also been observed in the absence of infection106.

In asthmatics, neutrophils can exert deleterious effects on the lungs via multiple mechanisms. While the release of NETs is important for pathogen elimination, they have also been proposed to contribute to airway inflammation in both asthma107,108 and COPD109. The association of NETs with lung injury is discussed previously in this article.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) can be produced by multiple cell types in asthmatic airways, including neutrophils. TGF-β is a profibrotic cytokine, and has been implicated in airway remodeling in asthma. Peripheral blood neutrophils of asthmatics release more TGF-β than in normal controls, and there is are more TGF-β-producing neutrophils in the lungs of asthmatics than in non-asthmatic lungs110. Neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) are neutrophil-derived mediators that contribute to airway inflammation. Neutrophil elastase increases CXCL-8 production by airway epithelium, recruiting more neutrophils into the lungs. It can also inactivate tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), an inhibitor of MMP-9111. MMP-9 itself is involved in extracellular matrix turnover and tissue repair, and may contribute to inflammatory cell migration112,113. An imbalance of MMP-9 compared to TIMP-1 has been observed in both adult and pediatric asthmatics114,115, and elevated MMP-9 is seen in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and with non-CF bronchiectasis, with increased MMP-9 correlating with lower FEV1116.

Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment

A growing body of research has demonstrated distinct roles of neutrophils in the cancer microenvironment. Activated neutrophils can kill tumor cells through ROS generation117,118 antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). One exciting therapeutic approach involves enhancing ADCC of neutrophils and macrophages directed against tumor cells through inhibition of the SIRPα-CD47 “don’t eat me” pathway119,120. Neutrophil activation can also drive tumor progression and metastasis through a number of pathways, including stimulation of thrombosis and angiogenesis, stromal remodeling, and impairment of T cell-dependent anti-tumor immunity121,122. NETs can facilitate tumor progression in tumor-bearing mice, and are a potential therapeutic target123–125. In addition, neutrophils can bind to circulating tumor cells and enhance hematogenous metastasis through enhancing tumor cell cycle progression126.

Although neutrophil heterogeneity has been recognized for decades 127, the concept of distinct neutrophil populations at the transcriptome and phenotypic level has been advanced over the past decade with better tools for molecular and cellular profiling. There is a growing appreciation of the plasticity of neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment at both the transcriptional 128 and metabolic levels 129 that can enhance or obstruct anti-tumor immunity. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) are a heterogeneous population of immature immunosuppressive myeloid cells that can have granulocytic (PMN-MDSC) or monocytic features. MDSC are most extensively studied in the setting of advanced cancer where tumor-derived factors stimulate disordered myelopoiesis, resulting in the expansion of MDSC that suppress T cell activation and impair anti-tumor immunity 130. Since neutrophil and PMN-MDSC have overlapping surface markers, PMN-MDSC are traditionally differentiated from neutrophils based on PMN-MDSC having a lower density and co-sedimenting with peripheral blood mononuclear cells after density-gradient centrifugation and PMN-MDSC suppressing T cell responses 131. Distinct from PMN-MDSC, tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN) are divided into N1 (anti-tumorigenic) or N2 (suppressive and pro-tumorigenic) populations, with distinct transcriptional profiles and functional properties 132,133. Though functionally similar to PMN-MDSC regarding suppression of T cell responses, the phenotype of N2 neutrophils is driven by responses to TGF-β133, and is not considered to result from disordered granulopoiesis. Singel et al. 122 recently showed that mature neutrophils are rendered immunosuppressive by exposure to ovarian cancer ascites and other malignant effusions, and that this suppressor function is dependent on multiple neutrophil effector functions, including complement signaling. Since mature neutrophils can phenocopy the suppressive function of PMN-MDSC 134, it is important to understand mechanisms driving the pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic properties of mature neutrophils distinct from disordered granulopoiesis. Neutrophil plasticity raises the possibility for therapeutically modulating neutrophils in multiple diseases, including cancer 128.

Conclusion

Neutrophils are an important component of the innate immune system, mediating both pathogen defense and inflammation, through multiple processes including phagocytosis, release of granular enzymes, oxidative burst, and NET formation. The future promises insight into additional poorly understood areas of neutrophil biology, including neutrophil heterogeneity, epigenetic regulation of neutrophil function, and the impact of the microbiome on neutrophils. Severe deficiencies in neutrophil number or function result in life-threatening immune deficiencies, while inappropriate or excessive activation of neutrophils cause host tissue damage in chronic inflammatory or autoimmune conditions. Neutrophils can have “off target” effects, where pathways that normally defend against infection are activated by non-infectious cues (e.g., products of cellular injury) and influence pathologic disorders ranging from autoimmunity to the tumor microenvironment. A greater understanding of neutrophil heterogeneity and plasticity in these conditions is expected to pave the way to new therapeutic approaches.

Box 1: Key Points.

Neutrophils are plentiful but short-lived in the peripheral blood, and function as key mediators of innate immune responses against extracellular pathogens.

Neutrophils exert antimicrobial effects through several processes, including toxic reactive oxygen species formation, enzymatic degradation, and NET formation

NETs play a pathogenic role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. They can directly kill epithelial and endothelial cells, and provide a scaffold for thrombus formation. Granular proteins and nucleic acids in NETs may act as autoantigens initiating and driving autoimmune diseases.

Impaired neutrophil immunity may manifest with predisposition to severe bacterial or invasive fungal infections. Genetic defects have been recognized leading to defects in neutrophil quantity, chemotaxis, oxidative function, granule proteins or release of granule contents.

Continued research is needed to advance our understanding of areas such as neutrophil heterogeneity, epigenetic regulation of neutrophils, and the impact of the microbiome on neutrophils.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: H. Lehman has received research contracts from Kedrion S.p.A., Leadiant Biosciences, and Takeda Ltd. B.H. Segal has served on a Data Review Committee for a Merck-sponsored clinical trial.

Contributor Information

Heather Lehman, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University at Buffalo, Chief, Division of Allergy/Immunology & Rheumatology, Fellowship Program Director, Allergy/Immunology, UBMD Pediatrics, 1001 Main Street, 5th Floor, Buffalo, NY 14203.

Brahm H. Segal, Chair, Department of Internal Medicine, Chief, Division of Infectious Diseases, Member, Dept. of Immunology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Professor of Medicine, University at Buffalo, Elm& Carlton Streets, Buffalo, NY 14263.

References

- 1.Bainton DF, Ullyot JL, Farquhar MG. The development of neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes in human bone marrow. J Exp Med 1971; 134(4): 907–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mora-Jensen H, Jendholm J, Fossum A, Porse B, Borregaard N, Theilgaard-Monch K. Technical advance: immunophenotypical characterization of human neutrophil differentiation. J Leukoc Biol 2011; 90(3): 629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wengner AM, Pitchford SC, Furze RC, Rankin SM. The coordinated action of G-CSF and ELR + CXC chemokines in neutrophil mobilization during acute inflammation. Blood 2008; 111(1): 42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dancey JT, Deubelbeiss KA, Harker LA, Finch CA. Neutrophil kinetics in man. J Clin Invest 1976; 58(3): 705–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Summers C, Rankin SM, Condliffe AM, Singh N, Peters AM, Chilvers ER. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol 2010; 31(8): 318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillay J, Den Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast LM, De Boer RJ, Borghans JA, et al. In vivo labeling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days. Blood 2010; 116(4): 625–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahoz-Beneytez J, Elemans M, Zhang Y, Ahmed R, Salam A, Block M, et al. Human neutrophil kinetics: modeling of stable isotope labeling data supports short blood neutrophil half-lives. Blood 2016; 127(26): 3431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ella K, Csepanyi-Komi R, Kaldi K. Circadian regulation of human peripheral neutrophils. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 57: 209–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melchart D, Martin P, Hallek M, Holzmann M, Jurcic X, Wagner H. Circadian variation of the phagocytic activity of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and of various other parameters in 13 healthy male adults. Chronobiol Int 1992; 9(1): 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niehaus GD, Ervin E, Patel A, Khanna K, Vanek VW, Fagan DL. Circadian variation in cell-adhesion molecule expression by normal human leukocytes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2002; 80(10): 935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas CJ, Schroder K. Pattern recognition receptor function in neutrophils. Trends Immunol 2013; 34(7): 317–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee WL, Harrison RE, Grinstein S. Phagocytosis by neutrophils. Microbes Infect 2003; 5(14): 1299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Granulopoiesis and granules of human neutrophils. Immunol Rev 2016; 273(1): 11–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abo A, Webb MR, Grogan A, Segal AW. Activation of NADPH oxidase involves the dissociation of p21rac from its inhibitory GDP/GTP exchange protein (rhoGDI) followed by its translocation to the plasma membrane. Biochem J 1994; 298 Pt 3: 585–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furtmuller PG, Burner U, Obinger C. Reaction of myeloperoxidase compound I with chloride, bromide, iodide, and thiocyanate. Biochemistry 1998; 37(51): 17923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves EP, Lu H, Jacobs HL, Messina CG, Bolsover S, Gabella G, et al. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature 2002; 416(6878): 291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singel KL, Segal BH. NOX2-dependent regulation of inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016; 130(7): 479–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekhar KR, Crooks PA, Sonar VN, Friedman DB, Chan JY, Meredith MJ, et al. NADPH oxidase activity is essential for Keap1/Nrf2-mediated induction of GCLC in response to 2-indol-3-yl-methylenequinuclidin-3-ols. Cancer Res 2003; 63(17): 5636–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong X, Thimmulappa R, Kombairaju P, Biswal S. NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species mediate amplified TLR4 signaling and sepsis-induced mortality in Nrf2-deficient mice. J Immunol 2010; 185(1): 569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segal BH, Han W, Bushey JJ, Joo M, Bhatti Z, Feminella J, et al. NADPH oxidase limits innate immune responses in the lungs in mice. PLoS ONE 2010; 5(3): e9631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004; 303(5663): 1532–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018; 25(3): 486–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousefi S, Mihalache C, Kozlowski E, Schmid I, Simon HU. Viable neutrophils release mitochondrial DNA to form neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16(11): 1438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker MJ, Hollands A, Sanderson-Smith ML, Cole JN, Kirk JK, Henningham A, et al. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat Med 2007; 13(8): 981–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cell Microbiol 2006; 8(4): 668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papayannopoulos V Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2018; 18(2): 134–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almyroudis NG, Grimm MJ, Davidson BA, Rohm M, Urban CF, Segal BH. NETosis and NADPH oxidase: at the intersection of host defense, inflammation, and injury. Frontiers in immunology 2013; 4: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 2007; 176(2): 231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 2010; 191(3): 677–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metzler KD, Goosmann C, Lubojemska A, Zychlinsky A, Papayannopoulos V. A myeloperoxidase-containing complex regulates neutrophil elastase release and actin dynamics during NETosis. Cell Rep 2014; 8(3): 883–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mor-Vaknin N, Saha A, Legendre M, Carmona-Rivera C, Amin MA, Rabquer BJ, et al. DEK-targeting DNA aptamers as therapeutics for inflammatory arthritis. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 14252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohrbach AS, Slade DJ, Thompson PR, Mowen KA. Activation of PAD4 in NET formation. Front Immunol 2012; 3: 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenny EF, Herzig A, Kruger R, Muth A, Mondal S, Thompson PR, et al. Diverse stimuli engage different neutrophil extracellular trap pathways. Elife 2017; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosseinzadeh A, Thompson PR, Segal BH, Urban CF. Nicotine induces neutrophil extracellular traps. J Leukoc Biol 2016; 100(5): 1105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinod K, Witsch T, Farley K, Gallant M, Remold-O’Donnell E, Wagner DD. Neutrophil elastase-deficient mice form neutrophil extracellular traps in an experimental model of deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14(3): 551–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rochael NC, Guimaraes-Costa AB, Nascimento MT, DeSouza-Vieira TS, Oliveira MP, e Souza LF, et al. Classical ROS-dependent and early/rapid ROS-independent release of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps triggered by Leishmania parasites. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 18302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stojkov D, Amini P, Oberson K, Sokollik C, Duppenthaler A, Simon HU, et al. ROS and glutathionylation balance cytoskeletal dynamics in neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol 2017; 216(12): 4073–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skokowa J, Steinemann D, Katsman-Kuipers JE, Zeidler C, Klimenkova O, Klimiankou M, et al. Cooperativity of RUNX1 and CSF3R mutations in severe congenital neutropenia: a unique pathway in myeloid leukemogenesis. Blood 2014; 123(14): 2229–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horwitz MS, Duan Z, Korkmaz B, Lee HH, Mealiffe ME, Salipante SJ. Neutrophil elastase in cyclic and severe congenital neutropenia. Blood 2007; 109(5): 1817–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ancliff PJ, Blundell MP, Cory GO, Calle Y, Worth A, Kempski H, et al. Two novel activating mutations in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein result in congenital neutropenia. Blood 2006; 108(7): 2182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banka S, Chervinsky E, Newman WG, Crow YJ, Yeganeh S, Yacobovich J, et al. Further delineation of the phenotype of severe congenital neutropenia type 4 due to mutations in G6PC3. Eur J Hum Genet 2011; 19(1): 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilboux T, Lev A, Malicdan MC, Simon AJ, Järvinen P, Racek T, et al. A congenital neutrophil defect syndrome associated with mutations in VPS45. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(1): 54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roques G, Munzer M, Barthez MA, Beaufils S, Beaupain B, Flood T, et al. Neurological findings and genetic alterations in patients with Kostmann syndrome and HAX1 mutations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014; 61(6): 1041–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Pablos JL, Laurent L, Planchenault T, Verola O, et al. WHIM syndromes with different genetic anomalies are accounted for by impaired CXCR4 desensitization to CXCL12. Blood 2005; 105(6): 2449–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDermott DH, Liu Q, Velez D, Lopez L, Anaya-O’Brien S, Ulrick J, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of long-term, low-dose treatment of WHIM syndrome with the CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor. Blood 2014; 123(15): 2308–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDermott DH, Pastrana DV, Calvo KR, Pittaluga S, Velez D, Cho E, et al. Plerixafor for the Treatment of WHIM Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(2): 163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jung K, Elsner J, Emmendorffer A, Bittrich A, Lohmann-Matthes ML, Roesler J. Severe infectious complications in a girl suffering from atopic dermatitis were found to be due to chronic granulomatous disease. Acta Derm Venereol 1993; 73(6): 433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makaryan V, Zeidler C, Bolyard AA, Skokowa J, Rodger E, Kelley ML, et al. The diversity of mutations and clinical outcomes for ELANE-associated neutropenia. Curr Opin Hematol 2015; 22(1): 3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dale DC, Bolyard AA, Aprikyan A. Cyclic neutropenia. Semin Hematol 2002; 39(2): 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horwitz MS, Corey SJ, Grimes HL, Tidwell T. ELANE mutations in cyclic and severe congenital neutropenia: genetics and pathophysiology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2013; 27(1): 19–41, vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bar-Joseph G, Halberthal M, Sweed Y, Bialik V, Shoshani O, Etzioni A. Clostridium septicum infection in children with cyclic neutropenia. J Pediatr 1997; 131(2): 317–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Notarangelo LD, Badolato R. Leukocyte trafficking in primary immunodeficiencies. J Leukoc Biol 2009; 85(3): 335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson DC, Schmalsteig FC, Finegold MJ, Hughes BJ, Rothlein R, Miller LJ, et al. The severe and moderate phenotypes of heritable Mac-1, LFA-1 deficiency: their quantitative definition and relation to leukocyte dysfunction and clinical features. J Infect Dis 1985; 152(4): 668–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gresham HD, Graham IL, Anderson DC, Brown EJ. Leukocyte adhesion-deficient neutrophils fail to amplify phagocytic function in response to stimulation. Evidence for CD11b/CD18-dependent and -independent mechanisms of phagocytosis. J Clin Invest 1991; 88(2): 588–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luhn K, Wild MK, Eckhardt M, Gerardy-Schahn R, Vestweber D. The gene defective in leukocyte adhesion deficiency II encodes a putative GDP-fucose transporter. Nat Genet 2001; 28(1): 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gazit Y, Mory A, Etzioni A, Frydman M, Scheuerman O, Gershoni-Baruch R, et al. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency type II: long-term follow-up and review of the literature. J Clin Immunol 2010; 30(2): 308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuijpers TW, van de Vijver E, Weterman MA, de Boer M, Tool AT, van den Berg TK, et al. LAD-1/variant syndrome is caused by mutations in FERMT3. Blood 2009; 113(19): 4740–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Svensson L, Howarth K, McDowall A, Patzak I, Evans R, Ussar S, et al. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency-III is caused by mutations in KINDLIN3 affecting integrin activation. Nat Med 2009; 15(3): 306–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams DA, Tao W, Yang F, Kim C, Gu Y, Mansfield P, et al. Dominant negative mutation of the hematopoietic-specific Rho GTPase, Rac2, is associated with a human phagocyte immunodeficiency. Blood 2000; 96(5): 1646–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seger R, Roos D, Segal BH, Kuijpers TW. Chronic Granulomatous Disease: Genetics, Biology and Clinical Management. Open access textbook, NOVA Publishers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang YC, Segal BH, Holland SM, Miller GF, Kwon-Chung KJ. Virulence of catalase-deficient aspergillus nidulans in p47(phox)−/− mice. Implications for fungal pathogenicity and host defense in chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest 1998; 101(9): 1843–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Messina CG, Reeves EP, Roes J, Segal AW. Catalase negative Staphylococcus aureus retain virulence in mouse model of chronic granulomatous disease. FEBS Lett 2002; 518(1-3): 107–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, Feld JJ, Pike KM, Marciano BE, et al. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(27): 2600–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lanza F Clinical manifestation of myeloperoxidase deficiency. J Mol Med (Berl) 1998; 76(10): 676–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drummond RA, Franco LM, Lionakis MS. Human CARD9: A Critical Molecule of Fungal Immune Surveillance. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glocker EO, Hennigs A, Nabavi M, Schäffer AA, Woellner C, Salzer U, et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(18): 1727–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lanternier F, Pathan S, Vincent QB, Liu L, Cypowyj S, Prando C, et al. Deep dermatophytosis and inherited CARD9 deficiency. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(18): 1704–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drewniak A, Gazendam RP, Tool AT, van Houdt M, Jansen MH, van Hamme JL, et al. Invasive fungal infection and impaired neutrophil killing in human CARD9 deficiency. Blood 2013; 121(13): 2385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gazendam RP, van Hamme JL, Tool AT, van Houdt M, Verkuijlen PJ, Herbst M, et al. Two independent killing mechanisms of Candida albicans by human neutrophils: evidence from innate immunity defects. Blood 2014; 124(4): 590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drummond RA, Swamydas M, Oikonomou V, et al. CARD9(+) microglia promote antifungal immunity via IL-1beta- and CXCL1-mediated neutrophil recruitment. Nat Immunol 2019; 20(5): 559–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lekstrom-Himes JA, Dorman SE, Kopar P, Holland SM, Gallin JI. Neutrophil-specific granule deficiency results from a novel mutation with loss of function of the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein epsilon. J Exp Med 1999; 189(11): 1847–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gombart AF, Koeffler HP. Neutrophil specific granule deficiency and mutations in the gene encoding transcription factor C/EBP(epsilon). Curr Opin Hematol 2002; 9(1): 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fujishima S, Hoffman AR, Vu T, Kim KJ, Zheng H, Daniel D, et al. Regulation of neutrophil interleukin 8 gene expression and protein secretion by LPS, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 beta. J Cell Physiol 1993; 154(3): 478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cassatella MA. Neutrophil-derived proteins: selling cytokines by the pound. Adv Immunol 1999; 73: 369–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Radic M, Marion TN. Neutrophil extracellular chromatin traps connect innate immune response to autoimmunity. Semin Immunopathol 2013; 35(4): 465–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khandpur R, Carmona-Rivera C, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Gizinski A, Yalavarthi S, Knight JS, et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5(178): 178ra40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pillinger MH, Abramson SB. The neutrophil in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1995; 21(3): 691–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baici A, Salgam P, Cohen G, Fehr K, Boni A. Action of collagenase and elastase from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes on human articular cartilage. Rheumatol Int 1982; 2(1): 11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hitchon CA, El-Gabalawy HS. Oxidation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2004; 6(6): 265–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saffarzadeh M, Juenemann C, Queisser MA, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps directly induce epithelial and endothelial cell death: a predominant role of histones. PLoS One 2012; 7(2): e32366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thomas GM, Carbo C, Curtis BR, Martinod K, Mazo IB, Schatzberg D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps are associated with the pathogenesis of TRALI in humans and mice. Blood 2012; 119(26): 6335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Law SM, Gray RD. Neutrophil extracellular traps and the dysfunctional innate immune response of cystic fibrosis lung disease: a review. J Inflamm (Lond) 2017; 14: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young RL, Malcolm KC, Kret JE, Caceres SM, Poch KR, Nichols DP, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)-mediated killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence of acquired resistance within the CF airway, independent of CFTR. PLoS One 2011; 6(9): e23637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lefrancais E, Mallavia B, Zhuo H, Calfee CS, Looney MR. Maladaptive role of neutrophil extracellular traps in pathogen-induced lung injury. JCI Insight 2018; 3(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Etulain J, Martinod K, Wong SL, Cifuni SM, Schattner M, Wagner DD. P-selectin promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in mice. Blood 2015; 126(2): 242–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.von Bruhl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, Chandraratne S, Konrad I, Lorenz M, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med 2012; 209(4): 819–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(36): 15880–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martinod K, Demers M, Fuchs TA, Wong SL, Brill A, Gallant M, et al. Neutrophil histone modification by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110(21): 8674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Thomas GM, Martinod K, De Meyer SF, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10(1): 136–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schonermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med 2009; 15(6): 623–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2011; 187(1): 538–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leffler J, Stojanovich L, Shoenfeld Y, Bogdanovic G, Hesselstrand R, Blom AM. Degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps is decreased in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014; 32(1): 66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, Connolly J, Allantaz F, Xu Z, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3(73): 73ra20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, Frasca L, Conrad C, Gregorio J, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3(73): 73ra19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Crow MK. Type I interferon in the pathogenesis of lupus. J Immunol 2014; 192(12): 5459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leffler J, Gullstrand B, Jonsen A, Nilsson JÅ, Martin M, Blom AM et al. Degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps co-varies with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2013; 15(4): R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(21): 9813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Willis VC, Banda NK, Cordova KN, Chandra PE, Robinson WH, Cooper DC, et al. Protein arginine deiminase 4 inhibition is sufficient for the amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2017; 188(2): 263–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knight JS, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Smith CK, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(12): 2199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Atkinson TP, Bonitatibus GM, Berkow RL. Chronic granulomatous disease in two children with recurrent infections: family studies using dihydrorhodamine-based flow cytometry. J Pediatr 1997; 130(3): 488–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Remijsen Q, Vanden Berghe T, Wirawan E, Asselbergh B, Parthoens E, De Rycke R, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap cell death requires both autophagy and superoxide generation. Cell Res 2011; 21(2): 290–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith CK, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Tang C, Knight JS, Mathew A, Padilla RL, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-derived enzymes oxidize high-density lipoprotein: an additional proatherogenic mechanism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66(9): 2532–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Boone BA, Murthy P, Miller-Ocuin J, Doerfler WR, Ellis JT, Liang X, et al. Chloroquine reduces hypercoagulability in pancreatic cancer through inhibition of neutrophil extracellular traps. BMC Cancer 2018; 18(1): 678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sur S, Crotty TB, Kephart GM, Hyma BA, Colby TV, Reed CE, et al. Sudden-onset fatal asthma. A distinct entity with few eosinophils and relatively more neutrophils in the airway submucosa? Am Rev Respir Dis 1993; 148(3): 713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Simpson JL, Daly J, Baines KJ, Yang IA, Upham JW, Reynolds PN, et al. Airway dysbiosis: Haemophilus influenzae and Tropheryma in poorly controlled asthma. Eur Respir J 2016; 47(3): 792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lamblin C, Gosset P, Tillie-Leblond I, Saulnier F, Marquette CH, Wallaert B, et al. Bronchial neutrophilia in patients with noninfectious status asthmaticus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157(2): 394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Krishnamoorthy N, Douda DN, Bruggemann TR, Ricklefs I, Duvall MG, Abdulnour RE, et al. Neutrophil cytoplasts induce TH17 differentiation and skew inflammation toward neutrophilia in severe asthma. Sci Immunol 2018; 3(26). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dworski R, Simon HU, Hoskins A, Yousefi S. Eosinophil and neutrophil extracellular DNA traps in human allergic asthmatic airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127(5): 1260–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grabcanovic-Musija F, Obermayer A, Stoiber W, Krautgartner WD, Steinbacher P, Winterberg N, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation characterises stable and exacerbated COPD and correlates with airflow limitation. Respir Res 2015; 16: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chu HW, Trudeau JB, Balzar S, Wenzel SE. Peripheral blood and airway tissue expression of transforming growth factor beta by neutrophils in asthmatic subjects and normal control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106(6): 1115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Simpson JL, Scott RJ, Boyle MJ, Gibson PG. Differential proteolytic enzyme activity in eosinophilic and neutrophilic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172(5): 559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wenzel SE, Balzar S, Cundall M, Chu HW. Subepithelial basement membrane immunoreactivity for matrix metalloproteinase 9: association with asthma severity, neutrophilic inflammation, and wound repair. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111(6): 1345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Okada S, Kita H, George TJ, Gleich GJ, Leiferman KM. Migration of eosinophils through basement membrane components in vitro: role of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997; 17(4): 519–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tanaka H, Miyazaki N, Oashi K, Tanaka S, Ohmichi M, Abe S. Sputum matrix metalloproteinase-9: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 ratio in acute asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105(5): 900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Erlewyn-Lajeunesse MD, Hunt LP, Pohunek P, Dobson SJ, Kochhar P, Warner JA, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in preschool wheezers and their relationship to persistent wheeze. Pediatr Res 2008; 64(2): 194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bergin DA, Hurley K, Mehta A, Cox S, Ryan D, O’Neill SJ, et al. Airway inflammatory markers in individuals with cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. J Inflamm Res 2013; 6: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Clark RA, Klebanoff SJ. Neutrophil-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity: role of the peroxidase system. J Exp Med 1975; 141(6): 1442–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Clark RA, Klebanoff SJ. Role of the myeloperoxidase-H2O2-halide system in concanavalin A- induced tumor cell killing by human neutrophils. J Immunol 1979; 122(6): 2605–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Matlung HL, Babes L, Zhao XW, van Houdt M, Treffers LW, van Rees DJ, et al. Neutrophils Kill Antibody-Opsonized Cancer Cells by Trogoptosis. Cell reports 2018; 23(13): 3946–59 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Treffers LW, Zhao XW, van der Heijden J, Nagelkerke SQ, van Rees DJ, Gonzalez P, et al. Genetic variation of human neutrophil Fcgamma receptors and SIRPalpha in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity towards cancer cells. Eur J Immunol 2018; 48(2): 344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Singel KL, Segal BH. Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment: trying to heal the wound that cannot heal. Immunol Rev 2016; 273(1): 329–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Singel KL, Emmons TR, Khan ANH, Mayor PC, Shen S, Wong JT, et al. Mature neutrophils suppress T cell immunity in ovarian cancer microenvironment. JCI Insight 2019; 4(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cools-Lartigue J, Spicer J, McDonald B, Gowing S, Chow S, Giannias B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lee W, Ko SY, Mohamed MS, Kenny HA, Lengyel E, Naora H. Neutrophils facilitate ovarian cancer premetastatic niche formation in the omentum. J Exp Med 2019; 216(1): 176–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Albrengues J, Shields MA, Ng D, Park CG, Ambrico A, Poindexter ME, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science 2018; 361(6409). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Szczerba BM, Castro-Giner F, Vetter M, Krol I, Gkountela S, Landin J, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature 2019; 566(7745): 553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gallin JI. Human neutrophil heterogeneity exists, but is it meaningful? Blood 1984; 63(5): 977–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Veglia F, Tyurin VA, Blasi M, De Leo A, Kossenkov AV, Donthireddy L, et al. Fatty acid transport protein 2 reprograms neutrophils in cancer. Nature 2019; 569(7754): 73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Veglia F, Perego M, Gabrilovich D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol 2018; 19(2): 108–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nature communications 2016; 7: 12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sagiv JY, Michaeli J, Assi S, Mishalian I, Kisos H, Levy L, et al. Phenotypic diversity and plasticity in circulating neutrophil subpopulations in cancer. Cell reports 2015; 10(4): 562–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shaul ME, Levy L, Sun J, Mishalian I, Singhal S, Kapoor V, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils display a distinct N1 profile following TGFbeta modulation: A transcriptomics analysis of pro-vs. antitumor TANs. Oncoimmunology 2016; 5(11): e1232221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Aarts CEM, Hiemstra IH, Tool ATJ, Van Den Berg TK, Mul E, Van Bruggen R, et al. Neutrophils as Suppressors of T Cell Proliferation: Does Age Matter? Frontiers in immunology 2019; 10: 2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]