Abstract

Introduction

Periductal mastitis (PDM) is a complex benign breast disease with a prolonged course and a high risk of recurrence after treatment. There are many available treatments for PDM, but none is widely accepted. This study aims to evaluate the various treatment failure rates (TFR) of different invasive treatment measures by looking at recurrence and persistence after treatment. In this way, it sets out to inform better clinical decisions in the treatment of PDM.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases for eligible studies about different treatment regimens provided to PDM patients that had been published before October 1, 2019. We included original studies written in English that reported the recurrence and/or persistence rates of each therapy. Outcomes were presented as pooled TFR and 95% CI for the TFR.

Results

We included 27 eligible studies involving 1,066 patients in this study. We summarized 4 groups and 10 subgroups of PDM treatments, according to the published studies. Patients treated minimally invasively (group 1) were subdivided into 3 subgroups and pooled TFR were calculated as follows: incision and drainage (n = 73; TFR = 75.6%; 95% CI 27.3–100%), incision alone (n = 74; TFR = 20.1%; 95% CI 0–59.9%), and breast duct irrigation (n = 123; TFR = 19.4%; 95% CI 0–65.0%). Patients treated with a minor excision (excision of the infected tissue and related duct; group 2) were divided into 4 subgroups and pooled TFR were calculated as follows: wound packing alone (n = 127; TFR = 2.1%; 95% CI 0–5.2%), primary closure alone (n = 66; TFR = 37.1%; 95% CI 9.5–64.8%), primary closure under antibiotic treatment cover (n = 55; TFR = 4.8%; 95% CI 0–11.4%), and additional nipple part removal (n = 232; TFR = 9.6%; 95% CI 5.8–13.4%). Patients treated with a major excision (excision of the infected tissue and the major duct; group 3) included the following 2 subgroups: patients treated with a circumareolar incision (n = 142; TFR = 7.5%; 95% CI 0.4–14.7%) and patients treated with a radial incision of the breast (n = 78; TFR = 0.6%; 95% CI 0–3.6%). Group 4 contained patients receiving different major plastic surgeries. The pooled TFR of this group (n = 86) was 3.4% (95% CI 0–7.5%).

Conclusion

Breast duct irrigation, which is the most minimally invasive of all of the treatment options, seemed to yield good outcomes and may be the first-line treatment for PDM patients. Minor excision methods, except for primary closure alone, might be enough for most PDM patients. Major excision, especially with radial incision, was a highly effective salvage therapy. The major plastic surgery technique was also acceptable as an alternative treatment for patients with large lesions and concerns about breast appearance. Incision and drainage and minor excision with primary closure alone should be avoided for PDM patients. Further research is still needed to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of PDM and explore more effective treatments for this disease.

Keywords: Periductal mastitis, Treatment, Recurrence rate, Failure treatment, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Periductal mastitis (PDM), also known as plasma cell mastitis [1], periareolar abscess [1], Zuska disease [2], and mammillary fistula [3], is a form of chronic nonlactational mastitis. The common clinical symptoms of PDM are: nipple discharge, a subareolar breast mass, a periareolar breast abscess, and a mammary duct fistula [4]. The etiology of PDM is not yet clear [5]. Some studies have shown PDM to be likely associated with cigarette smoking [2, 6, 7, 8], nipple retraction [9, 10, 11, 12], and other disease processes related to lactation [3]. The pathogenesis of PDF is complex [13]. Obstruction of lactiferous ducts that might have been damaged by the accumulation of secretions and cell debris is regarded as a major predisposing factor [3, 14]. In postoperative pathological assessments, subacute or chronic inflammation, dilated ducts with amorphous debris and/or sinus formation with a squamous lining and keratin plug have commonly been described [9, 15, 16, 17]. It has been speculated that obstructed lactiferous ducts continuously expand and are damaged, owing to the accumulation of secretions and cell debris, and these ducts rupture, with aerobic and anaerobe invasion; inflammation develops and spreads to the interstitial tissue around the duct, and finally an inflammation mass and abscesses with or without a fistula develop further due to bacterial invasion [9, 15, 16, 17].

Though PDM is rare, it causes great pain in patients with a prolonged disease course and there is a high risk of recurrence after treatment. So far, there is no consensus regarding the different treatment options for PDM. To our knowledge, only 1 study has reported the effectiveness of conservative treatment (antibiotics only), and it showed poor outcomes [18]. Cessation of smoking is encouraged as an adjuvant treatment for PDM patients because smoking may be a risk factor for PDM development and recurrence, according to current studies [2, 6, 7, 8]. Surgery, rather than conservative management, is a popular method for PDM, according to published studies [3, 12, 18]. In order to achieve improved outcomes and good cosmetic results while minimizing the rate of recurrence, different surgical procedures have been designed and performed in PDM patients. However, the effects of each surgical procedure are different [3, 5, 9, 13]. Hence, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the outcomes of different invasive treatments in order to inform better clinical decisions in treating PDM.

Materials and Methods

Retrieval Strategy

We comprehensively searched all studies published before October 1, 2019, in the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases, using the following search terms in the title/abstract search box: “periductal mastitis,” “plasma cell mastitis,” “periareolar abscess,” “zuska's disease,” “mammillary fistula,” “periareolar abscesses,” “subareolar abscess,” “subareolar abscesses,” “recurrent breast abscess,” “recurrent breast abscesses,” “zuska disease,” “mammillary fistulas,” “mammary fistula,” “mammary fistulas,” “lactiferous duct fistula,” “lactiferous duct fistulas,” “fistulas of lactiferous ducts,” and “fistula of lactiferous duct.” In addition, we added the related literature mentioned in the retrieved articles to supplement the search article database.

Subjects and Interventions

The subjects included patients with a typical clinical manifestation of PDM, plasma cell mastitis, periareolar abscess, mammary fistula, and pathological features in the breast.

In this review, we divided all of the invasive treatments into 4 major groups according to the invasiveness of the procedure and the tissue it contained, and we further divided these into 10 subgroups based on different details of processing. Minimally invasive surgery (group 1) included the following 3 subgroups: incision and drainage, incision alone (incision of abscess or fistula and awaiting healing by granulation), and breast duct irrigation (ductal lavage with or without ultrasound-guided minimally invasive irrigation by a water pump or a fiber optic ductoscopy). Minor excision (excision of infected tissue and the related duct; group 2) included the following 4 subgroups: wound packing, primary closure alone (without antibiotic use), primary closure under antibiotic treatment cover, and additional nipple part (containing the plugged duct) removal. Major excision (excision of infected tissue and major duct; group 3) included the following 2 subgroups: circumareolar incision and radial incision. Cases treated with major plastic surgery were placed in group 4. Mastectomy was not analyzed in this article because it is usually the last choice for PDM patients.

Observation Index

Treatment failure rate (TFR) was defined as the recurrence or persistence rates of PDM after treatment. Recurrence refers to the future reappearance of symptoms of PDM, such as skin changes, an inflammatory mass, subareolar breast abscesses, mammary fistulas, or nipple discharge. Persistence refers to the above signs remaining after treatment.

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case/control studies; studies reporting the recurrence and/or persistence rate of different treatments for PDM; studies in which the treatment methods for PDM were specific and clear to classify; studies published in English; and studies for which the full text was available.

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were: reviews, case reports, and reference abstracts; studies in which the treatment methods for PDM were not specific and clear to classify; and studies that did not report recurrence and/or not healing rates.

Data Extraction

The titles and abstracts of all of the retrieved studies were reviewed independently by 2 researchers (H.X. and R.L.) to exclude those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining articles were examined to determine whether they reported TFR in different treatments for PDM and whether the studies described the treatment methods in detail. The related literature mentioned in the above articles was also searched for additional data. We chose to include the study with the largest sample size if some of the same subjects were included in cases where the data came from the same research unit and partially duplicated the patients.

Data Analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using R 3.3.3 software. The pooled incidence and 95% CI were calculated. We also used I2 for quantitative analysis of heterogeneity. I2 ≥50% suggested significant heterogeneity among the included studies, and a randomized effects model was used for the meta-analysis. Otherwise, a fixed effects model was used when I2 <50%.

Results

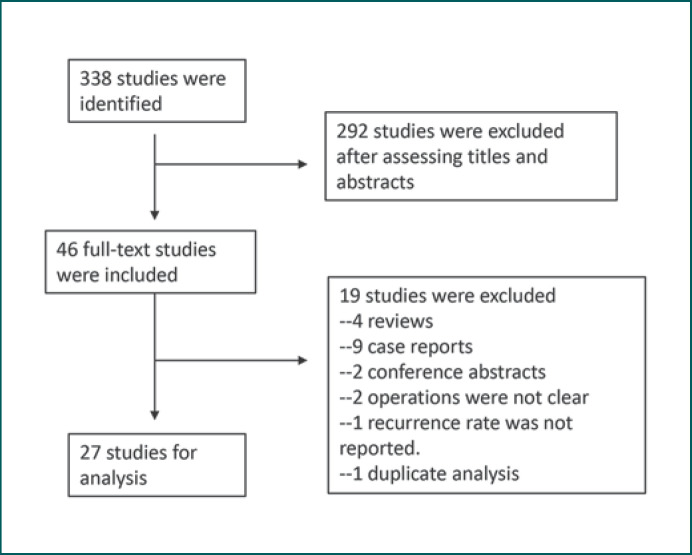

We searched 338 potentially relevant citations published in English before October 1, 2019, and 46 studies were identified in detail. Of those, we selected 27 studies that reported recurrence and persistence rate data for different treatments of PDM (Fig. 1). A total of 1,066 patients were included. Follow-up periods varied from 0.5 months to 17 years (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review.

Table 1.

Treatment failure rates of all studies included in the meta-analysis

| Patients, n | Mean/median follow-up time (range) | Cure, n | Recurrence, n | Treatment failure, n | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incision and drainage (n = 83) | ||||||

| Meguid et al. [18] | 16 | 4 y | 16 | 16 | 16 | 100.0 |

| Lannin [28] | 67 | NA | 33 | NA | 34 | 50.7 |

| Incision alone (n = 74) | ||||||

| Lambert et al. [27] | 15 | 25 m (1–75) | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Watt-Boolsen et al. [22] | 59 | 8 y | 59 | 24 | 24 | 40.6 |

| Breast duct irrigation (n = 123) | ||||||

| Wu et al. [19] | 119 | NA (6–36 m) | 117 | 0 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Chen et al. [30] | 4 | 6 m (0.5–21) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Minor excision with wound packing (n = 127) | ||||||

| Atkins [3] | 28 | NA | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lambert et al. [27] | 25 | 25 m (1–75) | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bundred et al. [20] | 9 | NA (1–7 y) | 8 | 1 | 2 | 22.2 |

| Hanavadi et al. [36] | 6 | 20 w (4–104) | 6 | 1 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Beechey-Newman et al. [33] | 59 | 6 y | 59 | 5 | 5 | 8.5 |

| Minor excision with primary closure alone (n = 66) | ||||||

| Lambert et al. [27] | 8 | 25 m (1–75) | 8 | 1 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Bundred et al. [20] | 21 | NA (1–7 y) | 15 | 5 | 11 | 52.4 |

| Hanavadi et al. [36] | 3 | 20 w (4–104) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 33.3 |

| Li et al. [9] | 34 | 4.2 y (0.1–11.5) | 34 | 22 | 22 | 64.7 |

| Minor excision with primary closure under antibiotics cover (n = 55) | ||||||

| Bundred et al. [20] | 6 | NA (1–7 y) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dixon and Thompson [23] | 15 | 2.5 y | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meguid et al. [18] | 24 | 4 y | 24 | 4 | 4 | 16.7 |

| Hanavadi et al. [36] | 10 | 20 w (4–104) | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10.0 |

| Minor excision with additional nipple part removal (n = 232) | ||||||

| Habif et al. [14] | 152 | NA (NA to 13 y) | 152 | 14 | 14 | 9.2 |

| Powell et al. [40] | 6 | NA | 6 | 1 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Maier et al. [25] | 21 | 1970–1980a | 21 | 3 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Yanai et al. [38] | 5 | NA | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Li et al. [9] | 33 | 4.2 y (0.1–11.5) | 33 | 3 | 3 | 9.1 |

| Komenaka et al. [21] | 15 | 20.6 m (7–27) | 14 | 1 | 2 | 13.3 |

| Major excision with a circumareola incision (n = 142) | ||||||

| Hadfield [17] | 10 | 24 m (12–36) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hadfield [41] | 30 | NA (1–7 y) | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lannin [28] | 8 | 10 y (1–22) | NA | NA | 5 | 62.5 |

| Hartley et al. [42] | 13 | 1 y (3 m–17 y) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 46.2 |

| Dixon and Thompson [23] | 28 | 2.5 y | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hanavadi et al. [36] | 11 | 20 w (4–104) | 11 | 4 | 4 | 36.4 |

| Almasad [43] | 11 | 28 m (7–84) | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Taffurelli et al. [13] | 18 | 36 m | 18 | 2 | 2 | 11.1 |

| Zhang et al. [5] | 13 | 26 m (3–60) | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Major excision with a radial incision (n = 78) | ||||||

| Livingston and Arlen [29] | 10 | NA (1–7 y) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Lannin [28] | 26 | 10 y (1–22) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7.7 |

| Urban and Egeli [12] | 42 | 1947–1976b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Major plastic technique (n = 86) | ||||||

| Giacalone et al. [32] | 27 | 5 y (2–11) | 27 | 1 | 1 | 3.7 |

| Zhang et al. [37] | 47 | 2 y | 47 | 2 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Zhang et al. [5] | 12 | 26 m (3–60) | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

NA, not available; y, years; m, months; w, weeks.

The follow-up time is not available but the patients were treated from 1970 to 1980.

The follow-up time is not available but the patients were treated from 1947 to 1976.

Group 1: TFR of PDM Patients Treated Minimally Invasively

Incision and Drainage Subgroup

There were 2 studies (n = 83) in this subgroup. One

(n = 16) reported TFR as 100% and the other (n = 67) had a TFR of 50.7% (Table 1). The pooled TFR was 75.6% (95% CI 27.3–100.0%; I2 = 98%) in the subgroup (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pooled estimate of the TFR of PDM patients

| Treatment method | Pooled incidence of TFR, % | 95% CI | I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimally invasive surgery | |||

| Incision and drainage | 75.6 | 27.3–100.0 | 98 |

| Incise only | 20.1 | 0–59.9 | 96 |

| Breast duct irrigation | 19.4 | 0–65.0 | 73 |

| Minor excision | |||

| Wound packing | 2.1 | 0–5.2 | 47 |

| Primary closure alone | 37.1 | 9.5–64.8 | 78 |

| Primary closure under antibiotic cover | 4.8 | 0–11.4 | 44 |

| Additional nipple part removal | 9.6 | 5.8–13.4 | 0 |

| Major excision | |||

| A circumareola incision | 7.5 | 0.4–14.7 | 75 |

| A radial incision | 0.6 | 0–3.6 | 0 |

| Major plastic technique | |||

| Plastic techniques | 3.4 | 0–7.5 | 0 |

Incision Alone

There were 2 studies (n = 74) in this subgroup. One (n = 15) reported a TFR of 0%, and the other (n = 59) had a TFR of 40.6% (Table 1). We calculated a pooled estimate of TFR for this method of 20.1% (95% CI 0–59.9%; I2 = 96%; Table 2).

Breast Duct Irrigation Subgroup

Two studies (n = 123) reported the recurrence rate of PDM treated with breast duct irrigation. The study of Wu et al. [19] included 119 PDM patients, with a TFR of 1.7%. The other study involved had just 4 PDM patients, with a TFR of 50% (Table 1). A meta-analysis of the TFR revealed an overall estimate of 19.4% (95% CI 0–65.0%; I2 = 73%; Table 2).

Group 2: TFR of PDM Treated with Minor Excision

Wound Packing Subgroup

Five studies (n = 127) reported the recurrence rate of PDM patients treated with this method. Persistence rate was 11.1% in one study and 0% in each of the other 4 studies. All of the studies showed consistently low TFR ranging from 0 to 22.2% (Table 1). The pooled estimate for TFR of this treatment method was 2.1% (95% CI 0–5.2%; I2 = 47%; Table 2).

Primary Closure Alone Subgroup

Four studies (n = 66) were included in this subgroup. One study [20] reported a persistence rate of 28.6%, and that of the other studies was 0% (Table 1). The TFR of all 4 studies ranged from 12.5 to 64.7%. A meta-analysis of the TFR revealed the overall estimate to be 37.1% (95% CI 9.5–64.8%; I2 = 78%; Table 2).

Primary Closure under Antibiotic Cover Subgroup

There were 4 studies (n = 55) with small sample sizes in this subgroup. The TFR ranged from 0 to 16.7% (Table 1). The pooled estimates for TFR in PDM patients in this subgroup was 4.8% (95% CI 0–11.4%; I2 = 44%; Table 2).

Additional Nipple Part Removal Subgroup

Six studies (n = 232) used this treatment method in PDM patients. One study [21] reported a persistence rate of 6.7%, and that of the remaining studies was 0% each. All 6 studies showed consistently low TFR of 0, 9.1, 9.2, 13.3, 14.3, and 16.7%, respectively (Table 1). The pooled estimate for TFR for this treatment method was 9.6% (95% CI 5.8–13.4%; I2 = 0; Table 2).

Group 3: TFR of PDM Treated with Major Excision

Circumareola Incision Subgroup

Nine studies (n = 142) reported the recurrence rate for PDM treated via this method. The TFR varied a great deal among the included studies. Five had a TFR of 0, whereas the remaining 4 studies had a TFR of 11.1, 36.4, 46.2, and 62.5%, respectively (Table 1). The pooled estimate for TFR was 7.5% (95% CI 0–4.5%; I2 = 75%; Table 2).

Radial Incision Subgroup

Three studies (n = 78) reported recurrence rates for PDM treated with this method. All studies showed consistently low TFR of 0, 0, and 7.7%, respectively (Table 1). The pooled TFR was 0.6% (95% CI 0–3.6%; I2 = 0; Table 2).

Group 4: Major Plastic Surgery

This group consisted of 2 major plastic surgery methods, including transfer of a random breast dermo-glandular flap and periareolar oncoplastic techniques. Two studies came from the same unit, but the subjects were not in the same population, so we included both. Three studies (n = 86) reported TFR for PDM treated with plastic techniques. All 3 studies had consistently low TFR of 0, 3.7, and 4.3%, respectively (Table 1). The pooled TFR was 3.4% (95% CI 0–7.5%; I2 = 0; Table 2).

Discussion/Conclusion

Although PDM is not common, it causes great pain to patients and it is often refractory to conservative treatment [18]. Surgery is the major frequently applied treatment in patients with PDM, based on the reported studies [3, 12, 18, 22, 23]. In order to achieve favorable effects and cosmetic outcomes, and minimize the recurrence rate, different types of surgery have been designed and performed for PDM. However, the results vary. For a patient with PDM, doctors are not sure which treatment may be the best choice due to a lack of pooled and integrated data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of invasive treatment measures to evaluate the TFR of different invasive treatment methods in order to inform better clinical decisions in the treatment of PDM.

All but 3 studies had persistence rates of 0%, irrespectively of the applied treatments [19, 20, 21]. However, the recurrence rates of the different treatments ranged from 0 to 100% in those studies. We speculate that this may have been caused by different definitions of recurrence and healing in separate studies. Thus, we used TFR instead of persistence and recurrence rate to analyze which treatments may have the best therapeutic efficacy.

We divided all invasive treatment measures into 4 major groups, according to minimal invasiveness and the tissue excised. We further divided these into 10 subgroups based on different details of processing.

The minimally invasive surgery group (group 1) included 3 subgroups to pool TFR for incision and drainage, incision alone, and breast duct irrigation at 75.6, 20.1, and 19.4%, respectively. Clearly, incision and drainage was not a suitable treatment for PDM patients, which is consistent with the findings of other studies [11, 18, 24, 25, 26]. Instead, incision and drainage might increase the risk of mammary fistula and enlarge the disease range [11, 23, 24]. Because a possible fistula is more easily probed when the acute inflammation has decreased, incision and drainage is conducted to rapidly reduce acute inflammation [27]. One study showed that characteristics associated with successful medical management of incision and drainage were <2 recurrences of subareolar abscess and absence of a lactiferous duct fistula [28]. In the pooled analysis the TFR appeared to be lower when healing was awaited by granulation (20.1%), compared to incision and additional drainage (75.6%). However, the TFR of the incision alone subgroup varied greatly between published studies (40.6 vs. 0%) [22, 27]. We found that there were some differences in the way the procedures in the 2 studies had been managed [22, 27]. For example, in the study of Lambert et al. [27], the fistula was found initially with a lacrimal probe and laid open, while Watt-Boolsen et al. [22] simply incised the abscess, regardless of whether the potential fistula had been laid open or not. Management of the fistula was usually necessary for PDM. This was perhaps the main reason for the significant heterogeneity (I2 = 96%). Although patients with incision without drainage usually needed lengthy treatment with a dressing before they were healed (2–8 weeks) [24, 29], the reviewed reports indicate that incision alone, with better probing for the possible fistula, and careful nursing, might be preferable over drainage, led to many recurrences as reported in the article by Meguid et al. [18] and might promote disease progression [11, 23, 24]. This requires further study. Breast duct irrigation was the least invasive of all the treatments identified in the paper. Two studies explored the effectiveness of breast duct irrigation for PDM [19, 30]. The sample sizes and TFR varied a great deal between them (119 vs. 4% and 1.7 vs. 50%). Noticeably, different therapies targeting different stages of PDM were performed in the study of Wu et al. [19]. For example, PDM patients with fistula were treated with fiberoptic ductoscopy irrigation in combination with minimally invasive drainage irrigation, while patients with nipple discharge were treated with fiberoptic ductoscopy irrigation alone [19]. Although different therapies targeting different stages of PDM were performed in the study of Wu et al. [19], the key method is breast duct irrigation. Therefore, we put all of the management in the breast duct irrigation subgroup. This may be the main reason for the heterogeneity in this subgroup. The pooled TFR for the breast duct irrigation subgroup (19.4%) was lowest in the minimally invasive surgery group. The healing time was about 20 days, which seemed shorter than in the incision alone subgroup (2–8 weeks) [19, 24, 29]. These 2 studies provided important information suggesting that breast duct irrigation could be a first-line treatment with a low TFR, a short healing time, and minimal invasiveness for PDM patients. Note that I2 was over 50% in all 3 subgroups. Heterogeneity was significant among the included studies. We speculated that the heterogeneity mainly came from the small sample sizes and the different characteristics of the subjects, such as primary PDM or recurrent PDM, PDM with or without a lactiferous duct fistula, smoking, nipple retraction, and so on. For example, most of the subjects in the study of Lannin [28] were mainly primary PDM patients without a lactiferous duct fistula, while the subjects in the study of Meguid et al. [18] were patients with recurrence of PDM and/or appearance of a lactiferous duct fistula, and 23 of the 24 patients were smokers. In the 3 subgroups, the TFR gave little more than a basic overview of trends in successful treatment outcomes.

PDM presumably arises from the mammary ducts [14, 15, 29]. One study [31] showed that the recurrence rate was as high as 79% when the lactiferous ducts were not excised, while the recurrence rate decreased to 28% after this had been performed. Some researchers recommended entire excision of the involved duct (minor excision) to reach the best treatment outcome [14, 22, 23, 31]. However, this technique has not been standardized. According to the published studies, there are 4 subtypes of minor excision. We noticed that minor excision with wound packing (awaiting healing by granulation), primary closure under antibiotic treatment cover, and additional part of nipple removal had the lowest TFR, i.e., 2.1, 4.8, and 9.6%, respectively, whereas minor excision with primary closure without antibiotic use had the highest TFR, i.e., 37.1%. Clearly, minor excision with primary closure alone should be avoided in PDM patients. We saw that the pooled TFR fell to 4.8% when primary closure was covered with antibiotics. Therefore, antibiotics were necessary when the strategy of minor excision with primary closure was employed. The comparatively low TFR (2.1%) in the minor excision with wound packing subgroup, which is based on a larger number of patients from 5 studies with consistently low recurrence rates, indicates that this approach might be a suitable treatment strategy for PDM. We speculate that the reason for the low TFR is that the open wound was not conducive to growth of bacteria, especially anaerobic bacteria, which are often associated with high postoperative recurrence rates [31, 32]; however, this still requires further study. Unfortunately, the healing time usually needed for this treatment is 3–4 weeks [33]. During that time, patients need to have their wound dressed and nursed many times in hospital. The cosmetic outcomes might be unattractive [33], but the long-term cosmetic result is satisfactory [22]. These advantages and disadvantages should be explained to the patient before carrying out a surgical approach. Some studies showed that patients with recurrence tended to have nipple abnormalities, such as total or partial nipple retraction or central nipple invagination [22, 34]. Li et al. [9] reported that patients who underwent excision of a part or the whole nipple containing a plugged duct had a lower recurrence rate (9%) than those who did not (43%). We calculated that minor excision with additional part of nipple removal had a low TFR of 9.6%. Considering that inverted nipple may be a risk factor for a high recurrence rate in PDM patients [11, 34], those with an inverted nipple may be suitable for this treatment method [10]. In conclusion, minor excision could preserve nonaffected ducts and the ability to breast feed, which would be an advantage for young women. Besides minor excision with primary closure alone, the other 3 methods could be chosen according to the patient's wishes and clinical symptoms.

Some studies showed that PDM may be caused by infection in or around subareolar ducts lined by squamous epithelium and filled with keratin plugs [14, 15, 29]. Excision of the infected tissue and the major duct system that includes both the disease duct and the normal duct, which we defined as a major excision, has been conducted to minimize the recurrence rate. Among these, the most representative techniques were the Hadfield [17] operation and the Urban [35] operation. Hadfield [17] chose a circumareola incision, while Urban [35] chose a radial incision. We found that 9 studies preferred a circumareola incision in the way of the Hadfield [17] operation, while 3 studies chose a radial incision similar to the Urban [35] operation. The pooled TFR of the major excision with a circumareola incision subgroup and a radial incision were 7.5% (95% CI 0.4–14.7%; I2 = 78) and 0.6% (95% CI 0–3.6%; I2 = 0), respectively. In addition, the cosmetic result is acceptable with the radial incision method [28]. Clearly, these 2 methods, especially in the radial incision subgroup, achieved a low TFR since the tissue is broadly sliced out, so the recurrence rates are statistically significantly reduced. However, the procedure is highly invasive, which is why it is an effective salvage therapy. We can see that the TFR varied a great deal among the included studies in the circumareola incision subgroup, while all of the studies showed consistently low TFR in radial incision. The reasons for heterogeneity may include the following: (1) the surgical procedures were somewhat different; circumareola incision, unlike radial incision, is a more difficult surgical procedure and it is not easy to keep infected tissue and major duct clean, which might cause treatment failure; (2) the subjects of the studies had different stages of PDM, e.g., patients with a complex fistula (recurring PDM) had a TFR of 0, whereas those with a simple fistula (primary PDM) had a TFR of 50%, and they believed that major excision may be suitable for refractory PDM patients rather than patients with simple PDM [36]; however, many studies did not perform a subgroup analysis; and (3) the sample of studies in some subgroups was small.

Lastly, plastic surgery techniques comprise a variety of methods, such as transfer of a breast dermo-glandular flap [5, 37] and periareolar oncoplastic techniques [32]. We defined all of these methods as major plastic techniques in this paper. These methods also achieved a low long-term TFR (0–5.2%) and ensured comparably good cosmetic results. For patients with large lesions, the outcome of these surgical techniques was good because they removed as much tissue as needed and cosmetic results were achieved. The technique needs to be chosen in the context of patient factors and surgical experience, and one might choose to begin with a more noninvasive treatment.

Limitations and Expectations

First, the validity of the TFR was limited. We only included studies published in English. All of the studies apart from one [30] were retrospective and none was a randomized controlled trial. The sample size of many of the studies included in this paper was small. Besides, the subjects of the studies might also have had different characteristics and stages of PDM. All of these factors caused heterogeneity in the studies included in this paper. Heterogeneity was also significant among studies included in several subgroups, such as in the incision and drainage, incision only, breast duct irrigation, minor excision with primary closure only, and major excision with circumareola incision subgroups. When the group is smaller, the TFR should be interpreted with caution. In particular, in subgroups in which the I2 value is high in most cases and the confidence interval is often broad, TFR simply gives a rough overview. Calculation of pooled TFR from different studies may not be accurate, and therefore we cannot statistically compare rates between different treatment methods. Second, it may be more suitable to treat PDM patients of various clinical manifestations with different treatments [5, 18]. For primary PDM with abscess, minimally invasive surgery such as breast duct irrigation may be suitable to avoid a surgical procedure. Minor excision, except for primary closure without antibiotics, could be considered for PDM patients with an abscess and/or a simple fistula [36]. For patients with multiple recurrences after operative procedures, a major excision or major plastic surgery should be considered [5, 36]. However, many studies did not perform a subgroup analysis, so this could not be further addressed in this study. Third, we did not consider the influence of other risk factors, such as smoking and nipple inversion, on treatment outcomes. For example, cessation of smoking and inversion of a section of the nipple are important for PDM patients and could reduce TFR [13, 38, 39]. We did not find specific data regarding the effect of PDM and an inverted nipple section in the process of operative procedures on TFR. Therefore, the effect of removal of causes of PDM could not be addressed in this study.

Finally, the follow-up time was short in many studies. Although a study [22] showed that recurrence usually happened in the first year after treatment, long-term follow-up was necessary to gather more useful information.

In conclusion, surgery is the main treatment for PDM. In the minimally invasive surgery group, incision and drainage might be an unsuitable method for the management of most PDM patients, especially those with multiple recurrences and/or a fistula. Incision and packing, and better probing the possible fistula, might be preferable over incision and drainage, but this requires further study. Breast duct irrigation, which is the most minimally invasive of all the treatment options, appears to have shown good outcomes and may be the first-line treatment for PDM patients, but further study is necessary. Minor excision methods, except for primary closure alone, may be enough for most PDM patients. Different therapies, including minor excision with wound packing, primary closure under antibiotic cover, and additional nipple part removal, were performed based on clinical manifestations and the wishes of the PDM patients. Major excision, especially with radial incision, is a highly effective salvage treatment with low TFR but it is highly invasive. The major plastic surgery technique was also acceptable as an alternative treatment for patients with large lesions and concerns about appearance. Further research is still needed to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of PDM in order to provide more information for exploring effective treatments for this disease.

Statement of Ethics

All analyses were based on previously published studies, and thus no ethical approval or patient consent were required for this paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

Y.L. and H.X. conceived and designed this study. H.X., R.L., and Z.F. collected the data. H.X. and Y.L. analyzed the data. W.M., Q.Y., and H.F. provided critical revisions and ensured the accuracy and integrity of this study. H.X. and Y.L. wrote this paper.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate the statistical advice from the statisticians working in the Department of Epidemiology and Statistics, Peking University Cancer Hospital. We acknowledge R.M. of Emerald English Editing for the proofreading of this paper.

References

- 1.Hughes LE. Non-lactational inflammation and duct ectasia. Br Med Bull. 1991 Apr;47((2)):272–283. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuska JJ, Crile G, Jr, Ayres WW. Fistulas of lactifierous ducts. Am J Surg. 1951 Mar;81((3)):312–317. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(51)90233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins HJ. Mammillary fistula. BMJ. 1955 Dec;2((4954)):1473–1474. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4954.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon JM. Periductal mastitis/duct ectasia. World J Surg. 1989 Nov-Dec;13((6)):715–720. doi: 10.1007/BF01658420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Mao F, Guan J, Sun Q. Clinical characteristics, classification and surgical treatment of periductal mastitis. J Thorac Dis. 2018 Apr;10((4)):2420–2427. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.04.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schäfer P, Fürrer C, Mermillod B. An association of cigarette smoking with recurrent subareolar breast abscess. Int J Epidemiol. 1988 Dec;17((4)):810–813. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bundred NJ, Dover MS, Aluwihare N, Faragher EB, Morrison JM. Smoking and periductal mastitis. BMJ. 1993 Sep;307((6907)):772–773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6907.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furlong AJ, al-Nakib L, Knox WF, Parry A, Bundred NJ. Periductal inflammation and cigarette smoke. J Am Coll Surg. 1994 Oct;179((4)):417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Grant CS, Degnim A, Donohue J. Surgical management of recurrent subareolar breast abscesses: mayo Clinic experience. Am J Surg. 2006 Oct;192((4)):528–529. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caswell HT, Maier WP. Chronic recurrent periareolar abscess secondary to inversion of the nipple. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969 Mar;128((3)):597–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ming J, Meng G, Yuan Q, Zhong L, Tang P, Zhang K, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical modality of plasma cell mastitis: analysis of 91 cases. Am Surg. 2013 Jan;79((1)):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urban J, Egeli RA. Non-lactational nipple discharge. CA Cancer J Clin. 1978 May-Jun;28((3)):130–140. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.28.3.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taffurelli M, Pellegrini A, Santini D, Zanotti S, Di Simone D, Serra M. Recurrent periductal mastitis: surgical treatment. Surgery. 2016 Dec;160((6)):1689–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habif DV, Perzin KH, Lipton R, Lattes R. Subareolar abscess associated with squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts. Am J Surg. 1970 May;119((5)):523–526. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(70)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patey DH, Thackray AC. Pathology and treatment of mammary-duct fistula. Lancet. 1958 Oct;2((7052)):871–873. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)92304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo G, Dessauvagie B, Sterrett G, Bourke AG. Squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts (SMOLD) Clin Radiol. 2012 Nov;67((11)):e42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadfield J. Excision of the major duct system for benign disease of the breast. Br J Surg. 1960 Mar;47((205)):472–477. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004720504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meguid MM, Oler A, Numann PJ, Khan S. Pathogenesis-based treatment of recurring subareolar breast abscesses. Surgery. 1995 Oct;118((4)):775–782. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu HL, Yu JJ, Yu SL, Zhou BG, Bao SL, Dong Y. Clinical efficacy of fiberoptic ductoscopy in combination with ultrasound-guided minimally invasive surgery in treatment of plasma cell mastitis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2016;43((5)):742–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bundred NJ, Dixon JM, Chetty U, Forrest AP. Mammillary fistula. Br J Surg. 1987 Jun;74((6)):466–468. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komenaka IK, Pennington RE, Jr, Bowling MW, Clare SE, Goulet RJ., Jr A technique to prevent recurrence of lactiferous duct fistula. J Am Coll Surg. 2006 Aug;203((2)):253–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watt-Boolsen S, Rasmussen NR, Blichert-Toft M. Primary periareolar abscess in the nonlactating breast: risk of recurrence. Am J Surg. 1987 Jun;153((6)):571–573. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon JM, Thompson AM. Effective surgical treatment for mammary duct fistula. Br J Surg. 1991 Oct;78((10)):1185–1186. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitchen PR. Management of sub-areolar abscess and mammary fistula. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991 Apr;61((4)):313–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maier WP, Berger A, Derrick BM. Periareolar abscess in the nonlactating breast. Am J Surg. 1982 Sep;144((3)):359–361. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen AF, Al-Suliman N, Nielsen KR, Vejborg I, Severinsen N, Christensen H, et al. Ultrasound-guided drainage of breast abscesses: results in 151 patients. Br J Radiol. 2005 Mar;78((927)):186–188. doi: 10.1259/bjr/26372381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert ME, Betts CD, Sellwood RA. Mammillary fistula. Br J Surg. 1986 May;73((5)):367–368. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lannin DR. Twenty-two year experience with recurring subareolar abscess andlactiferous duct fistula treated by a single breast surgeon. Am J Surg. 2004 Oct;188((4)):407–410. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livingston SF, Arlen M. Ductal fistula of the breast. Ann Surg. 1962 Feb;155((2)):316–319. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196200000-00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen K, Zhu L, Hu T, Tan C, Zhang J, Zeng M, et al. Ductal Lavage for Patients With Nonlactational Mastitis: A Single-Arm, Proof-of-Concept Trial. J Surg Res. 2019 Mar;235:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Versluijs-Ossewaarde FN, Roumen RM, Goris RJ. Subareolar breast abscesses: characteristics and results of surgical treatment. Breast J. 2005 May-Jun;11((3)):179–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giacalone PL, Rathat G, Fournet S, Rouleau C. Surgical treatment of recurring subareolar abscess using oncoplastic techniques. J Visc Surg. 2010 Dec;147((6)):e389–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beechey-Newman N, Kothari A, Kulkarni D, Hamed H, Fentiman IS. Treatment of mammary duct fistula by fistulectomy and saucerization. World J Surg. 2006 Jan;30((1)):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yukun L, Ke G, Jiaming S. Application of Nipple Retractor for Correction of Nipple Inversion: A 10-Year Experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;40((5)):707–715. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urban JA. Excision of the major duct system of the breast. Cancer. 1963 Apr;16((4)):516–520. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196304)16:4<516::aid-cncr2820160413>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanavadi S, Pereira G, Mansel RE. How mammillary fistulas should be managed. Breast J. 2005 Jul-Aug;11((4)):254–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Lin Y, Sun Q, Huang H. Dermo-glandular flap for treatment of recurrent periductal mastitis. J Surg Res. 2015 Feb;193((2)):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanai A, Hirabayashi S, Ueda K, Okabe K. Treatment of recurrent subareolar abscess. Ann Plast Surg. 1987 Apr;18((4)):314–318. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gollapalli V, Liao J, Dudakovic A, Sugg SL, Scott-Conner CE, Weigel RJ. Risk factors for development and recurrence of primary breast abscesses. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Jul;211((1)):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell BC, Maull KI, Sachatello CR. Recurrent subareolar abscess of the breast and squamous metaplasia of the lactiferous ducts: a clinical syndrome. South Med J. 1977 Aug;70((8)):935–937. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197708000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadfield GJ. Further experience of the operation for excision of the major duct system of the breast. Br J Surg. 1968 Jul;55((7)):530–535. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800550709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartley MN, Stewart J, Benson EA. Subareolar dissection for duct ectasia and periareolar sepsis. Br J Surg. 1991 Oct;78((10)):1187–1188. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Almasad JK. Mammary duct fistulae: classification and management. ANZ J Surg. 2006 Mar;76((3)):149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]