Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Insulin response is related to overall health. Diet modulates insulin response. We investigated whether insulinemic potential of diet is associated with risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

We prospectively followed 63,464 women from the Nurses’ Health Study (1986–2016) and 42,880 men from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986–2016). Diet was assessed by food frequency questionnaires every 4 years. The insulinemic potential of diet was evaluated using a food-based empirical dietary index for hyperinsulinemia (EDIH), which was predefined based on predicting circulating C-peptide concentrations.

RESULTS

During 2,792,550 person-years of follow-up, 38,329 deaths occurred. In the pooled multivariable-adjusted analyses, a higher dietary insulinemic potential was associated with an increased risk of mortality from all-cause (hazard ratio [HR] comparing extreme quintiles: 1.33; 95% CI 1.29, 1.38; P-trend <0.001), cardiovascular disease (CVD) (HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.27, 1.46; P-trend <0.001), and cancers (HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.13, 1.28; P-trend <0.001). These associations were independent of BMI and remained significant after further adjustment for other well-known dietary indices. Furthermore, compared with participants whose EDIH scores were stable over an 8-year period, those with the greatest increases had a higher subsequent risk of all-cause (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.09, 1.18; P-trend <0.001) and CVD (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.01, 1.21; P-trend = 0.006) mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

Higher insulinemic potential of diet was associated with increased risk of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality. Adopting a diet with low insulinemic potential might be an effective approach to improve overall health and prevent premature death.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, of the 55.4 million deaths worldwide in 2019, 55% were due to 10 top causes (1). Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain leading causes of death in the U.S. and several other developed and developing countries (1). Diet plays an essential role in human health and diseases (2). Poor diet is estimated as the leading cause of premature death in the U.S. (3). Insulin response plays an important role in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes (T2D), CVD, and many types of cancers (4–6). Major risk factors of premature death, such as poor diet, physical inactivity, and obesity, contribute to insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia through stimulation of insulin secretion, triglyceride synthesis, and fat accumulation with downregulation of insulin receptor and postreceptor signaling (7).

Most previous studies have used the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) as contributors to an acute insulin response and reported discrepant findings regarding health outcomes (8,9). Several dietary patterns, such as a healthy plant-based diet and the Mediterranean diet, were associated with improved insulin response (10–12) and lower risk of all-cause and CVD mortality (13,14). However, scores or indices reflecting these dietary patterns were not developed to comprehensively capture the overall insulinemic potential, which might be an important mediator linking diet and multiple chronic diseases and conditions.

Our group previously developed an empirical food-based dietary index for hyperinsulinemia (EDIH), a weighted dietary pattern score that maximally predicts plasma C-peptide concentrations, irrespective of the macronutrient content (15). C-peptide, a valid marker of chronic insulin secretion, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of major chronic diseases (16,17). The EDIH score has been extensively applied in previous studies, with robust results on risk of chronic diseases (18–21). In the current study, we investigated the association of dietary insulinemic potential with risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality, and further evaluated the association between changes in dietary insulinemic potential and subsequent all-cause and cause-specific mortality in two large cohorts of U.S. women and men.

Research Design and Methods

Study Population and Design

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is an ongoing cohort study consisting of 121,700 female nurses aged 30–55 years at enrollment in 1976. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is a parallel cohort including 51,529 male professionals aged 40–75 years at baseline in 1986. In both cohorts, information about medical history, lifestyle, and health conditions has been collected by self-administered questionnaire every 2 years since baseline. The cumulative follow-up rates in both cohorts >90%.

For this analysis, we used 1986 as the baseline for both cohorts. Participants were excluded if they died before baseline, had a history of cancer, diabetes, or CVD at or before baseline, had missing dietary information, or had implausible energy intakes (<600 or >3,500 kcal/day in women, and <800 or >4,200 kcal/day in men). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and those of participating registries as required. The completion of self-administered questionnaires was considered to imply informed consent.

Dietary Assessment and EDIH

Diet was assessed using validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) with >130 items administered every 4 years. The questionnaires inquired how often, on average, participants had consumed a specified portion size of each food during the preceding years to ascertain dietary intakes. The overall reproducibility and validity of the FFQ have been demonstrated in prior studies using 24-h recalls and multiweek weighted dietary records as reference measurements of diet (22–24).

The EDIH score was developed in a sample of 5,812 women in the NHS to empirically capture the insulinemic potential of the whole diet. Briefly, EDIH was derived based on 39 predefined food groups from FFQs by using stepwise regression models to identify a dietary pattern most predictive of circulating C-peptide concentration, which is considered a valid marker of long-term insulin secretion. The EDIH score is a weighted sum of 18 food groups (Supplementary Table 1), with higher scores indicating higher insulinemic potential of the whole diet and lower scores suggesting lower insulinemic potential. The validity of EDIH was evaluated in 2 independent cohorts and was strongly associated with circulating C-peptide concentration (15). In the current study, we calculated the EDIH score for each participant using FFQs data in each 4-year circle and also assessed changes in EDIH scores from 1986 to 1994 to evaluate their associations with subsequent risk of death.

Ascertainment of Deaths

Deaths were identified from vital records of states and the National Death Index or reported by the participants’ families and the U.S. postal system. This search was supplemented by reports from next of kin and postal authorities. Using these methods, we were able to ascertain >98% of the deaths in each cohort. A physician, who was blinded to the data, reviewed death certificates and medical records to classify the cause of deaths according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth and Ninth Revision (ICD-8 and ICD-9). Death from CVD was defined as code 390–458 (ICD-8) or 390–459 (ICD-9), and death from cancer was defined as code 140–207 (ICD-8) or 140–208 (ICD-9).

Ascertainment of Covariates

Information on lifestyle and other potential risk factors was collected at baseline and updated biennially during follow-up through self-administrated questionnaires, including age, body weight, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, aspirin use, multivitamin use, menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (NHS only), family history of chronic diseases (myocardial infarction, diabetes, and cancer), baseline hypertension, and baseline hypercholesterolemia in both cohorts. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated person-years of follow-up from the date of the return of the baseline questionnaire until the date of death or the end of follow-up (June 2016 for NHS and January 2016 for HPFS), whichever came first. We used the cumulative average of EDIH scores calculated from baseline to the censoring events to capture long-term dietary intake and reduce within-person variation. Of note, EDIH scores were adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for quintiles of EDIH in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality risk, with the reference category being the lowest quintile. The dose-response relationship of EDIH with mortality risk was assessed using restricted cubic spline regression. All analyses were stratified by age in month and calendar year. In the multivariable-adjusted model, we adjusted for race (White and non-White), smoking status (never, past, or current), current aspirin use (yes or no), physical activity (<3, 3–9, 9–18, 18–27, ≥27 MET/week), multivitamin use (yes or no), menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (premenopausal, postmenopausal [never, past, or current hormone use], NHS only), family history of myocardial infarction (yes or no), family history of diabetes (yes or no), family history of cancer (yes or no), baseline hypertension (yes or no), and baseline hypercholesterolemia (yes or no). Additionally, we ran a multivariable-adjusted model further adjusting for BMI (<23, 23–25, 25–30, 30–35, ≥35 kg/m2). Test for trend was evaluated by assigning the median value to each quintile and modeling it as a continuous variable.

For the analyses of changes in the dietary insulinemic potential, we set the initial cycle at 1986 and the baseline at 1994. We calculated the difference in EDIH scores over this 8-year period and categorized it into quintiles from the largest decrease (quintile 1) to the largest increase (quintile 5). Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate HR and 95% CI for the association between EDIH changes and mortality risk. The Cox models were stratified by age and calendar year and adjusted for the initial (1986) EDIH score, race, smoking status (never-never, never-past, past-past, current-past, never-current, past-current, or current-current), initial and changes in physical activity (quintiles), family history of myocardial infarction, diabetes, or cancer, baseline (1994) aspirin use, multivitamin use, and menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (NHS only), baseline hypertension or hypercholesterolemia, initial BMI, and weight changes (quintiles). We also examined associations of 12-year (1986–1998; baseline, 1998) and 16-year (1986–2002; baseline, 2002) changes in the EDIH score with subsequent total and cause-specific mortality.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings. First, we performed subgroup analyses and assessed statistical interactions according to cohort, BMI, alcohol intake, and physical activity. Second, we additionally adjusted for the consumption of food groups that are the major contributors to the EDIH (alcohol, coffee, red and processed meat, and fruits and vegetables) to assess whether any of these components are mostly or entirely accounting for the association of EDIH with mortality. Third, we adjusted for Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED), and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) to examine the added value of EDIH over the well-known dietary scores in overall health condition. Finally, we stopped updating diet after diagnosing intermediate outcomes (diabetes, CVD, and cancers) and conducted 4-year lag analyses to minimize reverse causation from existing health conditions.

Analyses were performed separately in each cohort and then pooled to obtain the overall effect using a fixed-effect model. However, we pooled the data for the restricted cubic spline regression and subgroup analysis. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute). Statistical tests were two-sided, and P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Our study included 63,464 women from the NHS and 42,880 men from the HPFS. Participants’ characteristics according to quintiles of EDIH score during follow-up are reported in Table 1. Compared with participants with lower EDIH scores, those in the highest quintile tended to have higher BMI and lower physical activity levels and were more likely to have a family history of diabetes. They also reported less consumption of dietary fiber, alcohol, and coffee, but higher intake of red meat and processed meat. During 30 years of follow-up (2,792,550 person-years), we documented 38,329 deaths in the two cohorts, including 9,153 deaths from CVD and 11,534 deaths from cancers.

Table 1.

Age-adjusted characteristics of participants across the entire follow-up period, according to quintiles of the EDIH score in the NHS (1986–2016) and the HPFS (1986–2016)*

| NHS | HPFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 5 | Quintile 1 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 5 | |

| Age, years | 66.1 (10.5) | 65.5 (10.8) | 62.9 (10.5) | 65.9 (11.4) | 65.0 (11.6) | 62.4 (11.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.7 (3.4) | 25.3 (4.2) | 27.4 (5.3) | 25.0 (3.1) | 25.8 (3.3) | 26.8 (3.9) |

| Physical activity, MET-h/week | 21.8 (20.5) | 16.3 (16.3) | 13.3 (13.8) | 36.3 (32.3) | 29.3 (27.2) | 27.1 (28.4) |

| White, % | 98.3 | 97.7 | 97.6 | 95.4 | 94.9 | 95.0 |

| Current smoking, % | 11.2 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 6.2 |

| Current aspirin use (yes), % | 51.9 | 51.0 | 48.1 | 58.9 | 59.2 | 57.0 |

| Multivitamin use (yes), % | 60.5 | 58.6 | 53.9 | 58.1 | 55.7 | 51.2 |

| Baseline hypertension, % | 17.1 | 21.7 | 27.3 | 16.2 | 17.9 | 18.8 |

| Baseline hypercholesterolemia, % | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 9.0 |

| Family history of | ||||||

| myocardial infarction (yes), % | 25.7 | 26.2 | 26.3 | 32.9 | 31.6 | 31.1 |

| Family history of diabetes (yes), % | 25.9 | 28.5 | 31.1 | 18.1 | 18.8 | 19.0 |

| Family history of cancer (yes), % | 48.5 | 48.1 | 46.2 | 25.1 | 26.2 | 24.2 |

| Any use of postmenopausal hormone (yes), % | 62.4 | 62.0 | 61.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Dietary intake | ||||||

| Total energy, kcal/day | 1,850 (451) | 1,668 (442) | 1,818 (474) | 2,104 (546) | 1,885 (527) | 2,103 (583) |

| Total carbohydrates, g/day† | 207.1 (30.9) | 203.5 (24.9) | 190.2 (26.2) | 256.8 (42.9) | 243.6 (34.9) | 226.5 (34.8) |

| Total protein, g/day† | 70.5 (10.0) | 74.0 (10.3) | 75.4 (11.7) | 85.7 (13.3) | 90.4 (12.9) | 93.7 (14.5) |

| Total fat, g/day† | 51.7 (9.3) | 55.1 (8.2) | 60.1 (8.5) | 62.6 (12.9) | 69.8 (11.0) | 77.0 (11.0) |

| Saturated fat, g/day† | 17.4 (4.4) | 18.8 (3.7) | 20.9 (3.7) | 20.1 (5.8) | 23.3 (4.9) | 26.4 (4.8) |

| Monounsaturated fat, g/day† | 19.5 (4.1) | 20.8 (3.6) | 22.9(3.7) | 24.2 (5.7) | 27.0 (4.8) | 30.0 (4.8) |

| Polyunsaturated fat, g/day† | 10.2 (2.4) | 10.5 (2.2) | 10.9 (2.3) | 12.8 (3.3) | 13.2 (2.8) | 13.6 (2.7) |

| Total fiber, g/day† | 20.4 (5.6) | 18.5 (4.3) | 16.1 (3.7) | 25.4 (7.7) | 21.9 (5.7) | 18.9 (4.7) |

| Alcohol, g/day | 10.4 (12.0) | 4.6 (7.7) | 3.7 (7.7) | 16.8 (16.8) | 10.2 (12.5) | 8.1 (11.9) |

| Coffee, servings/day | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.4) | 4.3 (2.4) | 3.2 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.3) |

| Red meat, servings/week | 2.3 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.7) | 4.2 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.0) | 3.9 (2.3) | 6.3 (3.4) |

| Processed meat, servings/week | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.3) | 2.6 (2.2) | 1.3 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.8) | 3.7 (3.4) |

Data are presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables and percentage of participants for categorical variables.

NA, not applicable.

All variables are standardized to the age distribution of the study population, except for age. EDIH scores were adjusted for energy intake using the residual method.

Energy-adjusted values.

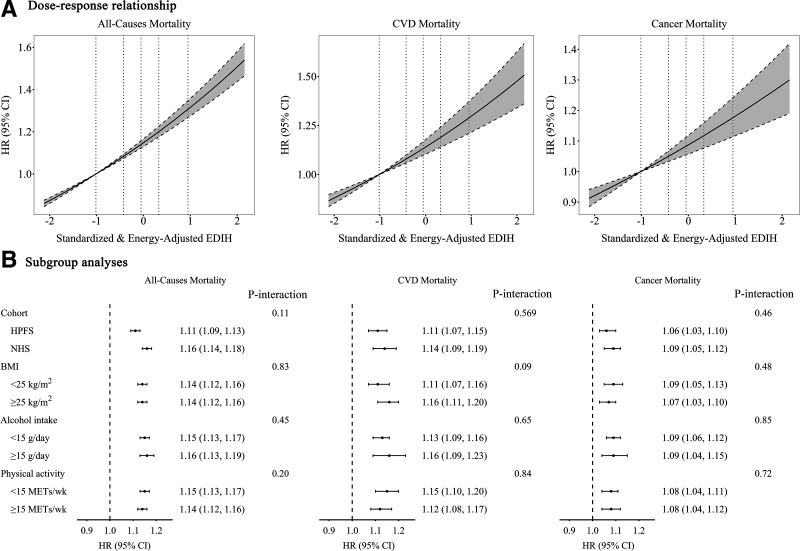

Age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted analyses showed a consistently positive association between EDIH and mortality risk (Table 2). The pooled multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for participants in the highest quintile of EDIH compared with those in the lowest quintile were 1.33 (95% CI 1.29, 1.38; P-trend <0.001) for all-cause mortality, 1.37 (95% CI 1.27, 1.46; P-trend <0.001) for CVD mortality, and 1.20 (95% CI 1.13, 1.28; P-trend <0.001) for cancer mortality. Additional adjustment for BMI did not materially alter the associations between EDIH and mortality risk. We observed a linear relationship between EDIH and risk of mortality from all-cause, CVD, and cancer (all P for linearity <0.001) (Fig. 1A). For each 1-SD increase in EDIH scores, all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality risk was higher by 15% (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.13, 1.16), 14% (HR 1.14; 95% CI 1.10, 1.18), and 9% (HR 1.09; 95% CI 1.06, 1.12), respectively.

Table 2.

HRs (95% CIs) of all-cause and cause-specific mortality according to EDIH in NHS and HPFS pooled*

| Quintile of EDIH | P-trend† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| All-cause mortality | |||||||

| NHS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 3,923/341,804 | 4,193/341,780 | 4,270/341,641 | 4,434/341,090 | 4,290/340,573 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.05 (1.00, 1.09) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.31 (1.25, 1.36) | 1.59 (1.53, 1.67) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.33 (1.28, 1.40) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.08) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.36 (1.30, 1.43) | <0.001 | |

| HPFS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 3,358/217,313 | 3,581/217,085 | 3,489/217,323 | 3,515/217,074 | 3,276/216,867 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.26 (1.20, 1.32) | 1.47 (1.40, 1.54) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.25) | 1.33 (1.27, 1.40) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 1.33 (1.26, 1.40) | <0.001 | |

| Pooled | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 7,281/559,117 | 7,774/558,865 | 7,759/558,964 | 7,949/558,164 | 7,566/557,440 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.06 (1.03, 1.10) | 1.13 (1.10, 1.17) | 1.29 (1.24, 1.33) | 1.54 (1.49, 1.59) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) | 1.19 (1.15, 1.23) | 1.33 (1.29, 1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.13) | 1.21 (1.17, 1.25) | 1.35 (1.30, 1.39) | <0.001 | |

| CVD mortality | |||||||

| NHS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 741/341,804 | 817/341,780 | 892/341,641 | 851/341,090 | 845/340,573 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.18) | 1.26 (1.14, 1.39) | 1.35 (1.23, 1.50) | 1.81 (1.63, 1.99) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.12) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.25) | 1.16 (1.05, 1.28) | 1.39 (1.25, 1.54) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.03, 1.26) | 1.34 (1.20, 1.48) | <0.001 | |

| HPFS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 974/217,313 | 1,043/217,085 | 995/217,323 | 1,053/217,074 | 942/216,867 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.09 (1.00, 1.20) | 1.10 (1.00, 1.20) | 1.32 (1.20, 1.44) | 1.50 (1.37, 1.65) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) | 1.23 (1.12, 1.34) | 1.35 (1.23, 1.48) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.97, 1.14) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) | 1.19 (1.09, 1.31) | 1.27 (1.15, 1.39) | <0.001 | |

| Pooled | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 1,715/559,117 | 1,860/558,865 | 1,887/558,964 | 1,904/558,164 | 1,787/557,440 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.15) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.33 (1.25, 1.42) | 1.63 (1.53, 1.75) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.10) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.26) | 1.37 (1.27, 1.46) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.11) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.30 (1.21, 1.39) | <0.001 | |

| Cancer mortality | |||||||

| NHS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 1,281/341,804 | 1,265/341,780 | 1,199/341,641 | 1,327/341,090 | 1,274/340,573 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.25) | 1.28 (1.19, 1.39) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.26) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.27) | <0.001 | |

| HPFS | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 1,027/217,313 | 1,076/217,085 | 1,046/217,323 | 1,033/217,074 | 1,006/216,867 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.07 (0.98, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.27) | 1.36 (1.24, 1.48) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.16) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.22) | 1.26 (1.15, 1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.16) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.22) | 1.26 (1.15, 1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Pooled | |||||||

| Cases/person-years | 2,308/559,117 | 2,341/558,865 | 2,245/558,964 | 2,360/558,164 | 2,280/557,440 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) | 1.32 (1.24, 1.39) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.11 (1.05, 1.18) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.28) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable + BMI | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 1.11 (1.05, 1.18) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.28) | <0.001 | |

EDIH scores were adjusted for energy intake using the residual method. All analyses were conducted using Cox models stratified by age and calendar years. Multivariable adjusted models were further adjusted for race, smoking status, physical activity, current aspirin use, multivitamin use, family history of cancer, family history of diabetes, family history of myocardial infraction, baseline hypertension, baseline hypercholesterolemia, and menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use for women.

The P-trend was calculated by assigning the median to all the participants in the quintile and modeling as continuous variables.

Figure 1.

Association of EDIH with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. A: The dose-response relationship is shown. Reference levels were set to the median EDIH values of the first quintile (−1.01). Vertical dotted lines indicate median values of each EDIH quintile (−1.01, −0.43, −0.05, 0.33, and 0.95). Solid lines indicate HRs, and dashed lines depict 95% CIs. No spline variables were selected in the analyses. All P for linearity <0.001. B: Subgroup analysis results are presented. All models in A and B were stratified by cohort, age, and calendar years, and were adjusted for race, smoking status, physical activity, current aspirin use, multivitamin use, family history of cancer, family history of diabetes, family history of myocardial infraction, baseline hypertension, baseline hypercholesterolemia, BMI, and menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use for women.

The strong associations between EDIH and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality persisted across cohorts and strata of BMI, alcohol intake, and level of physical activity (Fig. 1B) when we further adjusted for the consumption of food items that were major contributors to the EDIH scores (alcohol, coffee, red and processed meat, and fruits and vegetables) (Supplementary Table 2), when we stopped updating diet after the development of intermediate outcomes including diabetes, CVD, and cancers (Supplementary Table 3), or when we introduced a 4-year lag between the dietary exposure and death outcome (Supplementary Table 4). Further adjustment for other dietary scores, including AHEI (r for the correlation with EDIH = −0.41 in NHS and −0.45 in HPFS), aMED (r for the correlation with EDIH = −0.31 in NHS and −0.36 in HPFS), and DASH (r for the correlation with EDIH = −0.45 in NHS and −0.47 in HPFS), did not change the associations between EDIH and subsequent risk of death from all-cause, CVD, and cancer (Supplementary Table 5).

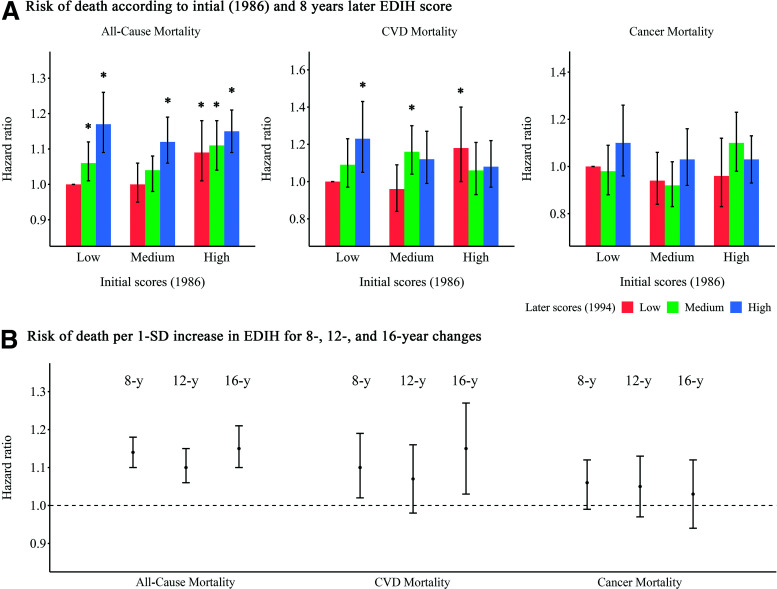

In the analyses for association between changes in EDIH score and mortality risk, compared with participants whose EDIH scores were relatively stable (quintile 3), those with the greatest increase (quintile 5) had a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.09, 1.18; P-trend <0.001) and CVD mortality (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.01, 1.21; P-trend = 0.006) (Supplementary Table 6). These positive associations persisted after further adjusting for weight change or introducing a 4-year lag (Supplementary Table 7). When we examined the joint association of scores at the initial assessment and 8 years later, compared with participants who had consistently low EDIH scores over time, participants with the largest increase in EDIH (low to high) had 20% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.20; 95% CI 1.12, 1.28) and 28% higher risk of CVD mortality (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.12, 1.47) (Fig. 2A). There were no significant associations between change in EDIH and cancer-related deaths. We observed similar associations between changes in EDIH scores over 12- and 16-year periods and subsequent mortality risk (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

HRs (95% CIs) for the association between changes in EDIH and risk of death. A: Risk of death is shown according to the initial EDIH score (1986) and the EDIH score 8 years later. Initial EDIH score are shown as low, medium, and high. At 8 years later, participants may have had a consistently low EDIH scores over time, a change from a low score to a medium or high score, a consistently medium score over time, a change from a medium score to a low or high score, a consistently high score over time, or a change from a high score to a low or medium score. The fully adjusted models were adjusted for the initial (1986) EDIH score, race, smoking status, initial and changes in physical activity, family history of myocardial infarction, diabetes, or cancer, baseline (1994) aspirin use, multivitamin use, and menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (NHS only), baseline hypertension or hypercholesterolemia, initial BMI, and weight changes. The error bars represent 95% CIs. *P < 0.05 for the associations of HRs compared with participants who had consistently low EDIH scores over time. B: Risk of death is shown per 1-SD increase in EDIH scores for preceding 8-, 12-, and 16-year changes. The fully adjusted HRs of death from any cause per 1-SD increase in EDIH for preceding 8, 12, and 16 years are shown. The error bars represent 95% CIs.

Conclusions

In the current study, we found that a higher dietary insulinemic potential was associated with a higher risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Compared with individuals consuming a diet with low insulinemic potential, those consuming hyperinsulinemia diets had a 33%, 37%, and 20% higher subsequent risk of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality, respectively. Results were confirmed by not further updating dietary scores after the diagnosis of intermediate outcomes or introducing a 4-year time lag. Furthermore, compared with participants whose EDIH scores remained stable over an 8-year period, those with the greatest increases had a higher subsequent risk of all-cause and CVD mortality.

Numerous studies have examined the association of various dietary patterns with mortality risk. Meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies reported that high adherence to healthy dietary patterns, including AHEI, aMED, and DASH, were associated with a 17 to 26% reduction in the risk of death from any cause (25,26). A similar reduction of risk was also observed in a pooled analysis that showed improved adherence to these dietary patterns over 12 years was consistently associated with a decreased risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality (27). However, previous studies have not comprehensively evaluated the insulinemic potential of diet and its relationship with risk of death. EDIH accounts for the impact of the whole diet on chronic insulin exposure, which might be more predictive of long-term dietary insulinemic potential on chronic disease and conditions. The strong positive associations of EDIH and subsequent mortality risk persisted after further adjustment for other dietary pattern scores (AHEI, aMED, and DASH), suggesting insulinemic potential of diet might play a unique and strong role in overall health.

Diet modulates insulin response. Hyperinsulinemic diets are rich in red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages but low in wine, coffee, fruits, and green leafy vegetables. These are in accordance with the inverse associations found for fruits, green leafy vegetables, and coffee and the positive associations found for sugar-sweetened beverages with mortality risk (28–30). Existing studies that addressed dietary insulinemic potential with mortality risk are sparse. According to our knowledge, only one study created a dietary score to measure the insulinemic potential of diet and found a positive association between insulinemic potential and mortality risk in 22,246 U.S. adults (31). However, dietary intake in that study was assessed using only a single 24-h recall, which cannot reflect the long-term impact and dynamic change of diets.

In our study, diet was assessed using validated semiquantitative FFQs with >130 items administered every 4 years. Benefiting from the repeated measurements of diet in our cohorts, we assessed not only the long-term impact but also changes in dietary insulinemic potential on subsequent all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Most previous studies have used GI and GL as contributors to an acute insulin response by evaluating the ability of carbohydrate-containing foods on raising postprandial blood glucose (32). However, the association of dietary glycemic potential with cardiometabolic outcomes and mortality is still unclear, as shown in two recent meta-analyses that reported discrepant findings (8,9). The discrepancies in findings of mortality risk might be because death is usually the result of a long sequence of multiple hazards, while GI and GL only reflect a short-term insulin response. In addition, noncarbohydrate factors, such as protein, fat, and alcohol, may also influence insulin secretion.

The EDIH score was developed based on predicting circulating C-peptide concentrations, which is considered a valid marker of long-term insulin secretion. Our recent analyses demonstrated that dietary insulinemic potential was positively associated with risk of T2D and colorectal cancer (18,19) and showed enhanced predictive potential for T2D risk compared with dietary glycemic potential (21). The observed higher mortality risk was associated with a higher EDIH in the current study, suggesting the link between chronic insulin exposure and unfavorable health outcomes and thereby rendering dietary modification to follow a diet with low insulinemic potential might be a potentially effective strategy for preventing premature death.

Adiposity is closely related to diet and can partly mediate its health effect (33). Our previous study showed that EDIH was associated with substantial long-term weight gain (20). In our study, BMI was not a mediator or an effect modifier for the association between dietary insulinemic potential and risk of mortality from all-cause, CVD, and cancers, suggesting that insulinemic potential of diet might be associated with risk of death through insulin response, which is not necessarily mediated by adiposity. The positive association between a hyperinsulinemic diet and the risk of subsequent death might be explained by the exacerbation of insulin-related pathological pathways. These align well with prior reports on hyperinsulinemia and risk of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality. The Helsinki Policemen Study, a small prospective study in a selected group of men with 22 years of follow-up, reported the positive association between insulin level during oral glucose tolerance tests and all-cause and CVD mortality (34). The result of hyperinsulinemia predicting all-cause mortality was further confirmed in a larger population-based prospective study of healthy men without diabetes (35). Apart from CVD mortality, the association between hyperinsulinemia and cancer death has been consistently observed as well. Previous studies conducted in Europe (36), North America (37), and Asia (38) all suggested that people with hyperinsulinemia were at higher risk of cancer mortality than those without hyperinsulinemia. The mechanisms underlying the association between hyperinsulinemic diet and mortality can be multifactorial. Hyperinsulinemic diet might contribute to acceleration of atherosclerosis progression through inhibiting nitric oxide production and stimulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, which is the major cause of CVD mortality (39). In addition, the direct mitogenic effect of insulin and the indirect effect through increased production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), and reduction of IGF1-binding proteins might help to explain the link between hyperinsulinemic diet and cancer mortality (40). Free IGF1 has mitogenic and antiapoptotic effects and has been suggested to be associated with increased cancer mortality (40). More research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking insulinemic potential of diet and overall health.

Major strengths of our study include the prospective design, the large sample size, and comprehensively collected data on diet and important covariates, which minimizes the potential for residual confounding. More importantly, we repeatedly measured dietary intakes, enabling us to assess the association of the long-term diet and its dynamic changes.

Nevertheless, our study also has several limitations. First, our dietary assessment was based on the self-reported questionnaire and might have measurement errors. Although, the FFQs used in the NHS and HPFS have been extensively validated against diet and biomarkers (22–24), the validation studies have not focused the comparability of EDIH to other food-based insulin response measures such as the insulin index.

Second, our study participants were health professionals and were mostly White, and our analyses did not address the potential variability in mortality risk associated insulin resistance, which might limit the generalizability. However, we postulate that our health professional cohorts could also be considered an advantage because they allowed us to collect accurate information on dietary and lifestyle variables and minimize confounding by socioeconomic status. Furthermore, we suggest that the biological mechanisms would not differ qualitatively in other populations, although we acknowledge that the magnitudes of the association might vary.

Third, the possibility of reverse causation cannot be entirely ruled out. However, we excluded participants with known major chronic diseases at baseline. Also, our results were robust in sensitivity analyses of introducing a 4-year lag and stopping updating diet after major chronic diseases developed. Finally, as with all observational studies, we cannot confirm causality and completely exclude unmeasured confounding.

In conclusion, we found that higher insulinemic potential of diet was strongly associated with higher risk of all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality. Adopting a diet with low insulinemic potential might be an effective approach to improve overall health. Dietary recommendations emphasizing the importance of avoiding high insulinemic dietary patterns as one of the important components of a healthy diet could be considered for the primary prevention of premature death.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, and U01 CA167552), and Friends of FACES.

The sponsors had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. Y.W. conducted the analyses. Y.W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Y.W. and E.L.G. designed the research. F.K.T., D.H.L, T.T.F., W.C.W., and E.L.G. provide statistical expertise. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Y.W. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. This study was presented in abstract form at the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) 2021 Virtual Congress on Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, 9–14 September 2021.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.16906060.

This article is featured in a podcast available at diabetesjournals.org/journals/pages/diabetes-core-update-podcasts.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . The top 10 causes of death, 2020. Accessed 23 August 2021. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10- causes-of-death

- 2. Willett WC. Diet and health: what should we eat? Science 1994;264:532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, Echko M, et al.; US Burden of Disease Collaborators . The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA 2018;319:1444–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Czech MP. Insulin action and resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat Med 2017;23:804–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perry RJ, Shulman GI. Mechanistic links between obesity, insulin, and cancer. Trends Cancer 2020;6:75–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilcox G. Insulin and insulin resistance. Clin Biochem Rev 2005;26:19–39 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jayedi A, Soltani S, Jenkins D, Sievenpiper J, Shab-Bidar S. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1 December 2020 [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1854168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shahdadian F, Saneei P, Milajerdi A, Esmaillzadeh A. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of mortality from all causes and cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;110:921–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kahleova H, Tura A, Klementova M, et al. A plant-based meal stimulates incretin and insulin secretion more than an energy- and macronutrient-matched standard meal in type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover study. Nutrients 2019;11:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al.; Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT) Group . Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;359:229–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greco M, Chiefari E, Montalcini T, et al. Early effects of a hypocaloric, Mediterranean diet on laboratory parameters in obese individuals. Mediators Inflamm 2014;2014:750860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jafari S, Hezaveh E, Jalilpiran Y, et al. Plant-based diets and risk of disease mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci. 6 May 2021[Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1918628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tabung FK, Wang W, Fung TT, et al. Development and validation of empirical indices to assess the insulinaemic potential of diet and lifestyle. Br J Nutr 2016;116:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirai FE, Moss SE, Klein BE, Klein R. Relationship of glycemic control, exogenous insulin, and C-peptide levels to ischemic heart disease mortality over a 16-year period in people with older-onset diabetes: the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR). Diabetes Care 2008;31:493–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bo S, Gentile L, Castiglione A, et al. C-peptide and the risk for incident complications and mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: a retrospective cohort study after a 14-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167:173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tabung FK, Wang W, Fung TT, et al. Association of dietary insulinemic potential and colorectal cancer risk in men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;108:363–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee DH, Li J, Li Y, et al. Dietary inflammatory and insulinemic potential and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective U.S. cohort studies. Diabetes Care 2020;43:2675–2683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tabung FK, Satija A, Fung TT, Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL. Long-term change in both dietary insulinemic and inflammatory potential is associated with weight gain in adult women and men. J Nutr 2019;149:804–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jin Q, Shi N, Aroke D, et al. Insulinemic and inflammatory dietary patterns show enhanced predictive potential for type 2 diabetes risk in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care 2021;44:707–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, et al. Relative validity of nutrient intakes assessed by questionnaire, 24-hour recalls, and diet records as compared with urinary recovery and plasma concentration biomarkers: findings for women. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:1051–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al-Shaar L, Yuan C, Rosner B, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire in men assessed by multiple methods. Am J Epidemiol 2021;190:1122–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, et al. Validity of a dietary questionnaire assessed by comparison with multiple weighed dietary records or 24-hour recalls. Am J Epidemiol 2017;185:570–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwingshackl L, Bogensberger B, Hoffmann G. Diet quality as assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018;118:74–100.e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and health status: an updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:2769–2782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, et al. Association of changes in diet quality with total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med 2017;377:143–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller V, Mente A, Dehghan M, et al.; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017;390:2037–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ding M, Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Association of coffee consumption with total and cause-specific mortality in 3 large prospective cohorts. Circulation 2015;132:2305–2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malik VS, Li Y, Pan A, et al. Long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of mortality in US adults. Circulation 2019;139:2113–2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mazidi M, Katsiki N, Mikhailidis DP; International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP) . Effect of dietary insulinemia on all-cause and cause-specific mortality: results from a cohort study. J Am Coll Nutr 2020;39:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:362–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giovannucci E. A framework to understand diet, physical activity, body weight, and cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 2018;29:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pyörälä M, Miettinen H, Laakso M, Pyörälä K. Plasma insulin and all-cause, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality: the 22-year follow-up results of the Helsinki Policemen Study. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1097–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nilsson P, Nilsson JA, Hedblad B, Eriksson KF, Berglund G. Hyperinsulinaemia as long-term predictor of death and ischaemic heart disease in nondiabetic men: the Malmö Preventive Project. J Intern Med 2003;253:136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wargny M, Balkau B, Lange C, Charles MA, Giral P, Simon D. Association of fasting serum insulin and cancer mortality in a healthy population--28-year follow-up of the French TELECOM Study. Diabetes Metab 2018;44:30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsujimoto T, Kajio H, Sugiyama T. Association between hyperinsulinemia and increased risk of cancer death in nonobese and obese people: a population-based observational study. Int J Cancer 2017;141:102–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kira S, Ito C, Fujikawa R, Misumi M. Increased cancer mortality among Japanese individuals with hyperinsulinemia. Metabol Open 2020;7:100048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Di Pino A, DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis: implications for insulin-sensitizing agents. Endocr Rev 2019;40:1447–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Major JM, Laughlin GA, Kritz-Silverstein D, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Insulin-like growth factor-I and cancer mortality in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1054–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]