Abstract

Purpose

Despite the call to increase the number of radiation oncologists in Latin America, the quality, similarity, and number of residency training programs are unknown. We seek to describe the current state of residency programs in radiation oncology in Latin America.

Methods and Materials

Latin American Residents in Radiation Oncology performed a cross-sectional analysis of universities and training centers for radiation oncologists in Latin America. Latin American Residents in Radiation Oncology members identified and contacted current residents and specialists at each center to obtain information and documents that described their training curricula.

Results

As of 2020, 13 of 23 (56.5%) Latin American countries have radiation oncology training. Seventy-three training centers were identified (59 active and 14 inactive), associated with 28 universities. On average, each active center trains 2.6 new residents per year, and in total, 156 residents are trained annually. The average length of training programs is 3.6 years. Brazil and Mexico comprise 31 (52.5%) and 7 (11.9%) of active programs, respectively, and 64 (41.8%) and 50 (32.7%) residents, respectively. Training is available in 38 cities in 13 countries, and outside Brazil and Mexico, only 13 cities in 11 countries (9 capitals and 4 noncapital cities). Individualized curriculum documents were provided by 20 (83.3%) of 24 non-Brazilian programs, while 1 standardized guideline was provided for Brazilian training programs. These demonstrated variation between subjects taught, their devoted time, outside specialty rotations, and experiences in modern techniques. Seventy-five percent include volumetric modulated arc therapy, 70% stereotactic radiosurgery, and 55% stereotactic body radiation therapy training. One-hundred percent include gynecologic brachytherapy education and <50% brachytherapy education in other disease sites.

Conclusions

Training is highly centralized in capital cities. The number of trainees is insufficient to close the current human resource divide but is limited by available job openings. Over 50% of training programs now include technological training in stereotactic radiosurgery, stereotactic body radiation therapy, or volumetric modulated arc therapy; however, substantial variation still exists. The development of radiation oncology specialists must be improved and modernized to address the escalating demand for cancer care.

Introduction

The emergence and growth of cancer is a major challenge for health systems worldwide, especially for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as in Latin America.1 Epidemiologic projections for Latin America (current population over 600 million) show that the incidence of cancer will increase by 31.3% by 2030 and 66.3% by 2040 and that absolute cancer mortality will increase by 35.6% and 78.3%, respectively.2 To face this alarming situation, one of the necessary strategies is to focus on the training of radiation oncologists in Latin America.

Radiation therapy is one of the pillars in cancer treatment, and perhaps the most cost-effective cancer therapy in LMICs.3 In high-income countries, it is applied to 50% to 60% of patients with cancer for both curative and palliative intentions, and in Latin America the need may be even greater as a higher portion of patients present with later stage disease.4 Despite this, when planning health policies, worldwide radiation therapy is one of the last sectors to be considered, and as a consequence, access to radiation therapy is unacceptably low, especially in Africa and South America.5,6

Multiple groups have analyzed the need to invest in equipment and infrastructure to meet the enormous demand for radiation therapy that is expected in the upcoming years.5,7 However, radiation therapy departments also depend on critical factors that go beyond equipment, such as the training of a competent human team to ensure the quality and safety of skilled processes.8,9 Latin America has insufficient numbers of professionals to treat its patients with cancer; the deficit of radiation oncologists is 570 today and is projected to increase to 1419 by 2030.10 The pressure for physicians to treat high numbers of patients is difficult and may detract from structured learning activities, especially for residents in training.11 For this reason, in parallel with efforts to optimize the infrastructure for providing radiation therapy in Latin America, measures should be taken to optimize the training of specialists in the area.12

This remains an unaddressed challenge. With a complex labor market, coordinating the growth of radiation therapy centers in synchrony with the number of radiation oncology trainees has proved a difficult task.13, 14, 15 In addition to the focus on numbers, having well-trained and prepared radiation oncologists is essential to ensure universal access, efficacy, quality, and safety of radiation therapy in Latin America. As written in the International Basic Safety Standards published by the International Atomic Energy Agency, adequate training and education for radiation oncologists is a basic medical and social need.16,17

Several recommendations outlining fundamental training objectives for radiation therapy oncology residency programs have been published by organizations in Europe (European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology18 and International Atomic Energy Agency19), the United States (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education20), and Australia and New Zealand (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists21). Despite this, Latin America has no established guidelines, and currently each Latin American institution has its own training program. To date, the number, location, and similarity or heterogeneity between programs has remained unknown.

A recently formed international group of residents in radiation oncology experienced working in national and international health policy, economics, and medical education, Latin American Residents in Radiation Oncology (LARRO), seeks to address this problem. The purpose of this article is to describe the current state of radiation oncology training programs in Latin America and highlight recommendations toward promoting universal quality of radiation therapy training in the region.

Methods and Materials

Between October 2019 and July 2020, LARRO performed a cross-sectional analysis of universities and training centers for radiation oncologists in Latin America. A list of all the countries, universities, and training centers for radiation oncologists in Latin America was compiled through consultation between in-country radiation oncologists and residents in the LARRO network. After identifying each center, LARRO members contacted current residents and/or specialists to (1) learn general information about their residency program and to (2) request documents that existed about their training curriculum. Finally, an online query was performed to search for any public webpages with information about each residency program.

Relevant information was reviewed, including basic characteristics (ie, name and location of training program, number of resident positions per year, duration of training), courses taught and time spent in each, and training in specialized techniques, including brachytherapy, volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), radiosurgery (SRS), and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for lung cancers.

When information contained in documents was insufficient, a direct consultation was made with one or more residents of that program via cell phone or email communication to clarify points. When a discrepancy existed between documents and the reality of residents’ clinical practice, the information provided by residents currently in training was prioritized and recorded. To standardize the different time units reported for clinical rotations, the following conversions were used: 1 month = 4 weeks = 180 hours. National population data were gathered from the United National World Population Prospects 2019 Revision.22 All information was recorded and analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Training is available in 38 cities for 13 of 23 (56.5%) Latin American countries. Outside of Brazil and Mexico, only 13 cities in 11 countries had training programs, including 9 capital and 4 noncapital cities. The full list of countries, universities, and training centers in radiation oncology in Latin America is shown in Table 1. A total of 73 training programs were identified, with 59 of these currently active. Among active programs, Brazil comprises 31 (52.5%), Mexico 7 (11.9%), Chile 5 (8.5%), Argentina 4 (6.8%), and Peru 4 (6.8%). The others, Ecuador, Uruguay, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Venezuela, each have 1 training program in their country. Of these, 33 (55.9%) are associated with 25 universities, whereas the others are not university affiliated. Among the 14 inactive programs, 5 are in Brazil, 5 in Venezuela, 3 in Mexico, and 1 in Argentina. The geographic locations of cities with active and inactive programs are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summary of radiation oncology residency programs in Latin America

|

Countries without residency training programs (n = 10) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panamá, Surinam | ||||||||

|

Countries with residency training programs (n = 13) | ||||||||

| Country | City | University | Center for training | Number of new residents annually | Duration of training (y) | Current total residents | Curriculum available for review | Website for residency program |

| Argentina | Buenos Aires | None | Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (Mevaterapia) | 4 | 4 | 28 | Yes | Yes |

| Universidad de Buenos Aires | VIDT Oncología Radiante | 2-4 | 3 | Yes | Yes | |||

| Instituto de Oncologia Ángel H. Roffo | 1 | 3 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Hospital de Clínicas José de San Martín | Inactive | |||||||

| Córdoba | Universidad Nacional de Córdoba | Instituto Zunino | 0-1 | 4 | 2 | No | Yes | |

| Bolivia | Santa Cruz | Universidad Gabriel Rene Moreno | Instituto Oncológico del Oriente Boliviano | 2 | 4 | 8 | Yes | No |

| Brazil | Río Branco, Acre | None | Fundação Hospital do Acre | Inactive | ||||

| Salvador de Bahía, Bahía | None | Hospital São Rafael | Inactive | |||||

| Alagoinhas, Bahía | None | Hospital Aristides Maltez – Liga Baiana Contra o Câncer | 1 | 4 | 4 | Yes* | No | |

| Fortaleza, Ceará | None | Instituto do Câncer do Ceará | 2 | 4 | 8 | No | ||

| Brasilia, Distrito Federal | Universidade de Brasília | Hospital Universitário de Brasília | 1 | 4 | 4 | No | ||

| Vitória, Espírito Santo | None | Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia | 2 | 4 | 8 | No | ||

| Goiânia, Goiás | None | Hospital Araújo Jorge – Associação Combate ao Câncer de Goiás | 1 | 4 | 4 | No | ||

| Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais | None | Hospital da Baleia | 1 | 4 | 40 | Yes | ||

| None | Hospital Mater Dei | 1 | 4 | Yes | ||||

| None | Hospital Luxemburgo – Fundação Mario Penna | 1 | 4 | Yes | ||||

| Guarani, Minas Gerais | None | Hospital Marcio Cunha – Fundação Francisco Xavier | 2 | 4 | Yes | |||

| Montes Claros, Minas Gerais | None | Fundação de Saúde Dilson de Quadros Godinho | 2 | 4 | Yes | |||

| Muriaé, Minas Gerais | None | Fundação Cristiano Varella | 2 | 4 | Yes | |||

| Uberlândia, Minas Gerais | Universidade Federal de Uberlândia | Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia | 1 | 4 | Yes | |||

| Curitiba, Paraná | None | Hospital Erasto Gaertner – LPCC | 2 | 4 | 8 | No | ||

| Recife, Pernambuco | None | Instituto Materno Infantil Prof. Fernando Figueira | 1 | 4 | 4 | Yes | ||

| Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro | None | Instituto Nacional do Câncer | 6 | 4 | 24 | Yes | ||

| Natal, Rio Grande do Norte | None | Liga Norte Rio Grandense de Combate ao Câncer – CECAN | 1 | 4 | 4 | Yes | ||

| Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul | Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul | Hospital das Clínicas de Porto Alegre | 1 | 4 | 12 | No | ||

| Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde | Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre – Hospital Santa Rita | 2 | 4 | No | ||||

| Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul | None | Hospital São Vicente de Paulo de Passo Fundo | Inactive | |||||

| Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul | Universidade Federal de Santa Maria | Hospital Universitário da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria | Inactive | |||||

| Barretos, São Paulo | None | Hospital de Amor | 3 | 4 | 136 | Yes* | No | |

| Campinas, São Paulo | None | Hospital das Clínicas da Unicamp Campinas | 1 | 4 | Yes | |||

| Jaú, São Paulo | None | Hospital Amaral Carvalho (Jaú) | 2 | 4 | No | |||

| Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo | Universidade de São Paulo | Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto | 2 | 4 | No | |||

| Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicine da Universidade de São Paulo | 9 | 4 | Yes | |||||

| Rio Preto, São Paulo | None | Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de S. José do Rio Preto | 1 | 4 | No | |||

| São Paulo, São Paulo | None | Casa de Saúde Santa Marcelina | 2 | 4 | No | |||

| None | Hospital do Câncer A. C. Camargo | 5 | 4 | No | ||||

| None | Hospital São Paulo – Escola Paulista de Medicina | 2 | 4 | No | ||||

| None | Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual de São Paulo – IAMSPE | 2 | 4 | No | ||||

| None | Hospital Sírio Libanês | 2 | 4 | No | ||||

| None | Hospital Beneficência Portuguesa de São Paulo | 2 | 4 | No | ||||

| None | Instituto Dr Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho | 1 | 4 | No | ||||

| Botucatu, São Paulo | None | Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho – UNESP (Botucatu) | inactive | |||||

| Chile | Santiago | Universidad de Chile | Instituto Nacional del Cáncer - Clínica Las Condes | 1-3 | 3 | 23 | Yes | No |

| Universidad Católica | Centro del Cáncer Universidad Católica | 2 | 4 | Yes | No | |||

| Universidad de Los Andes | Fundación Arturo López Pérez | 2 | 3 | No | No | |||

| Universidad Diego Portales | Clínica IRAM | 1 | 3 | Yes | No | |||

| Valparaíso | Universidad de Valparaiso | Hospital Carlos Van Buren | 1 | 3 | 3 | Yes | No | |

| Colombia | Bogotá | Universidad Militar Nueva Granada | Instituto Nacional de Cancerología | 2 | 4 | 8 | Yes | No |

| Costa Rica | San José | Universidad de Costa Rica | Hospital México | 1-2 | 4 | 6 | Yes | No |

| Ecuador | Quito | Universidad Central del Ecuador | Hospital Carlos Andrade Marin / Hospital Militar / Hospital Oncológico Solon Espinoza (SOLCA) | 5 | 4 | 20 | Yes | Yes |

| Guatemala | Ciudad de Guatemala | Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala | Instituto de Cancerología Dr Bernardo Del Valle S. | 0-1 | 3 | 1 | No | No |

| México | Ciudad de México | Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México | Hospital de Oncología Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social (IMSS) | 3-13 | 3 | 78 | Yes† | No |

| Hospital General de México Dr Eduardo Liceaga | 3-13 | 3 | No | |||||

| Instituto Nacional de Cancerología | 3-13 | 3 | No | |||||

| Hospital Central Militar | 2 | 3 | No | |||||

| Escuela de Posgrado en Sanidad Naval | Inactive | |||||||

| Merida | Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social (IMSS) Mérida, Yucatán. | 3-13 | 3 | 24 | No | |||

| Monterrey | Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo León | IMSS Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad (UMAE) nº 25 Monterrey, Nuevo León | 3-13 | 3 | 24 | No | No | |

| Guadelajara | Universidad de Guadalajara | UMAE del Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente IMSS | 3-13 | 3 | 24 | Yes | No | |

| Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología | inactive | |||||||

| Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde | inactive | |||||||

| Paraguay | Capiatá | Universidad Nacional de Caaguazú | Instituto Nacional del Cáncer | 1 | 4 | 4 | Yes | No |

| Perú | Lima | Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia | Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas | 3 | 3 | 18 | Yes‡ | Yes |

| Clínica AUNA | 1 | 3 | Yes | |||||

| Universidad San Martín de Porres | INEN - Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins | 1 | 3 | Yes | No | |||

| Universidad Ricardo Palma | Clínica Ricardo Palma | 1 | 3 | Yes | No | |||

| Uruguay | Montevido | Universidad de la Republica | Hospital de Clínicas Dr Manuel Quintela / Instituto Nacional del Cáncer / Centro hospitalario Pereira Rosell | 6 | 4 | 24 | Yes | Yes |

| Venezuela | Barcelona | Universidad Central de Venezuela | Hospital Luis Razetti, Barcelona | Inactive | ||||

| Barquisimeto | Universidad Centro Occidental Lisandro Alvarado | Instituto Oncológico Dr Luis Razetti | Inactive | |||||

| Caracas | None | Hospital Dr Domingo Luciani, IVSS (Instituto Venezolano de los seguros sociales) | 2 | 3 | 6 | Yes | No | |

| None | Hospital Universitario de Caracas | Inactive | ||||||

| None | GURVE, Centro Clínico La Floresta | Inactive | ||||||

| Maracay | None | Instituto Oncológico Miguel Pérez Carreño, Maracay | Inactive | |||||

| Totals | 46 cities | 28 universities | 73 centers | 156 new residents yearly | 557 current residents | 21 of 25 available | 20 of 59 have websites | |

| Active | 38 cities | 25 universities | 59 centers | |||||

Brazil programs share the same curriculum.

In Mexico, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México programs share the same curriculum.

In Peru, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia programs share the same curriculum.

Fig. 1.

Map of active and inactive radiation oncology residency training in Latin America.

Shown in blue pins are cities with active radiation oncology residency training programs. Shown in black pins are cities with inactive residency training programs. Pins correspond to geographic program locations.

The average number of residents trained annually per center is 2.6, and the total number of residents trained annually per year is 156. Among annual trainees, Brazil comprises 64 (41.8%), Mexico 50 (32.7%), Chile 8 (5.2%), Argentina 8 (5.2%), Peru 6 (3.9%), Uruguay 6 (3.9%), Ecuador 5 (3.2%), Bolivia 2 (1.3%), Colombia 2 (1.3%), Venezuela 2 (1.3%), Costa Rica 1 (0.7%), Paraguay 1 (0.7%), and Guatemala 1 (0.7%). The average length of radiation oncology training is 3.6 years. The estimated number of residents in Latin America is 557. The total number of trainees per capita in Latin America is 1 per 1,107,370 people (Brazil 1 per 835,912; Mexico 1 per 868,415; Chile 1 per 738,937; Argentina 1 per 1,520,194; Peru 1 per 1,853,301; Uruguay 1 per 145,215; Ecuador 1 per 894,424; Bolivia 1 per 1,479,118; Colombia 1 per 6,408,231; Venezuela 1 per 4,784,159; Costa Rica 1 per 856,509; Paraguay 1 per 1,804,910; and Guatemala 1 per 18,249,860.

Curriculum documents were collected from radiation oncology residency programs successfully in 11 of 13 countries with established programs. Brazil has a uniform curriculum guideline for all training programs, whereas individualized curriculum documents were provided by 20 (83.3%) of the 24 non-Brazilian programs. In terms of the type of training institution (hospital, clinic, or institute), 11 (55%) are public, 3 (15%) are private, and 6 (30%) are mixed, meaning the residents rotate between at least 1 public and 1 private institution. Among training institutions, 12 (60%) provide a salary for all residents, 7 (35%) provide a salary only for certain residents who meet criteria (ie, from in-country), and 1 (5%) does not provide a salary for residents; instead, the residents must pay tuition.

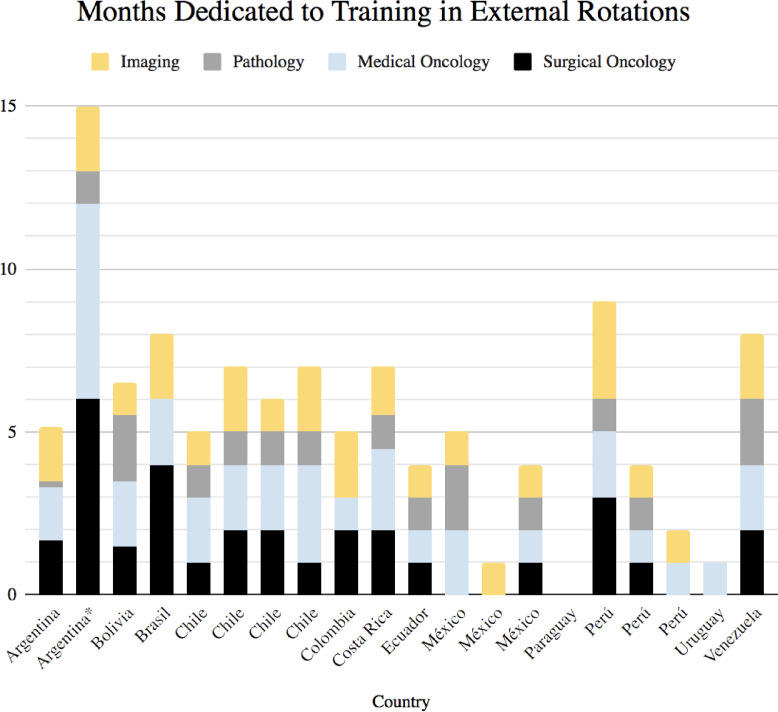

In almost all countries, residents must do 1 year of general medicine, usually in a rural community. Thereafter, they commence 3 to 4 additional years of radiation oncology training (this is similar to how residency is in the United States). Figure 2 summarizes time spent in external rotations during radiation oncology training. All rotations are performed on a full-time basis except for 1 program in Argentina, which includes part-time rotations throughout training.

Fig. 2.

Training in external rotations. The time in months dedicated to full-time training in external rotations (yellow = imaging, gray = pathology, blue = medical oncology, and black = surgical oncology) is shown for different residency programs. Programs are listed according to country of origin along the x-axis. *Program includes longitudinal part-time rotations.

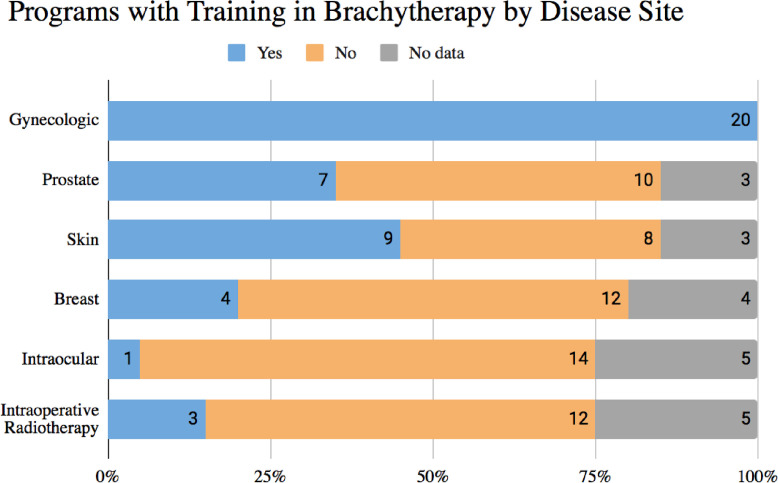

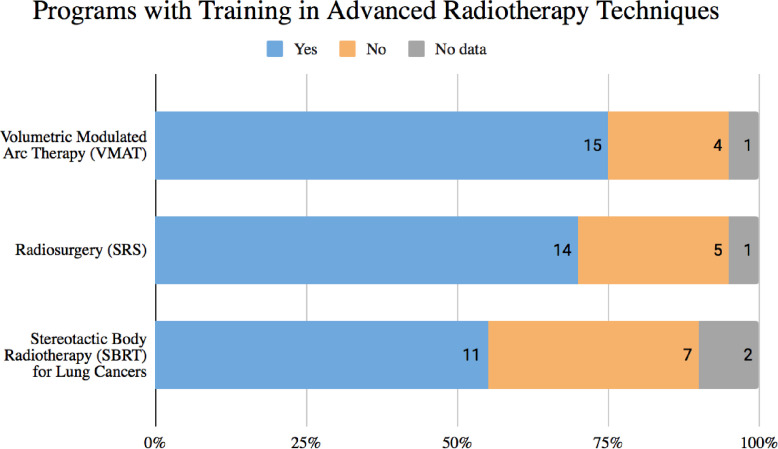

Regarding radiation oncology-specific training, radiobiology and medical physics courses both existed in 19 (95%) programs and did not exist in 1 (5%) program. Training in brachytherapy and advanced radiation therapy techniques is summarized in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, respectively. All (95%) but 1 (5%) program offer hands-on brachytherapy training. However, residents receive education in gynecologic brachytherapy at all programs. Additionally, at least 7 brachytherapy programs include prostate (35%), 9 skin (45%), 4 breast (20%), and 1 intraocular (5%). At least 3 (15%) intraoperative radiation therapy training programs exist. Finally, residents receive training in VMAT at 15 (75%), SRS at 14 (70%), and SBRT for lung at 11 (55%) of these 20 training programs.

Fig. 3.

Training in brachytherapy. The portion of residency training programs that include brachytherapy education in different disease sites is shown. Disease site categories included gynecologic, prostate, skin, breast, intraocular, and intraoperative radiation therapy.

Fig. 4.

Training in advanced radiation therapy techniques. The portion of residency training programs that include education in different modern radiation therapy techniques is shown. Techniques included volumetric modulated arc therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery, and stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Discussion

In response to the call to attention for radiation therapy development in Latin America, we provide the first published report of radiation oncology residency training programs in Latin America. The role of radiation oncology professionals is more important now than ever before in Latin America. By 2050, one-third of all cancer cases worldwide will be in Latin America, and up to 70% of these cases may require radiation therapy.2 Efforts are underway to meet the growing demand; it will require the upscaling of radiation therapy facilities and ensuring that well-trained staff are present and available to provide the highest quality care. Integral to this roadmap is understanding the current landscape and challenges for residents in radiation oncology.

In Latin America, there is very little exposure to the specialty of radiation oncology before residency. A typical medical student in Latin America is exposed to 0 or 1 lecture in radiation oncology throughout their education. Our investigation found only 20 of 59 radiation oncology residency programs had websites with public information, and these were limited to Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Peru, and Uruguay. As a result, radiation oncology is not a popular field, and almost all residents chosen enter radiation oncology with minimal-to-no familiarity.

In addition to the detriments of entering residency with little information about the specialty or career, there is a mismatch between educational needs and opportunities. Relative to their high-income country counterparts, countries in Latin America did not purchase and develop as much new radiation therapy equipment during the 1990s and 2000s (Dante Roa, personal communication, June 1, 2018). Consequently, there is an approximate 20-year gap in experience with new technology, during which time there was a bloom of mechanical innovation that introduced intensity modulated radiation therapy, VMAT, SRS, and SBRT. Professionals in Latin America have been working to close this gap; in fact, there is a current renaissance of technology and radiation therapy development as new technology is now replacing old equipment throughout many countries. However, the challenge remains for trainees that neither trainee nor faculty have the privilege of years of experience with these techniques and technologies, and both are learning together.

Currently, there are 59 active radiation oncology residency programs in 13 Latin American countries. Over half of these programs are concentrated in Brazil, with 31 programs (which train 64 new residents annually). Following is Mexico with 7 programs (50 new residents annually). The remaining 11 countries contain only 21 active programs (39 new residents annually). Combined, all programs train 156 new residents annually, and with an average program duration of 3.6 years, this represents 557 residents in training at a time. Training is only available in 38 cities for all 13 countries, and outside Brazil and Mexico, training is only available in 13 cities in 11 countries.

The limited and centralized nature of radiation therapy services and training is an area of focus for improvement. Many countries whose populations range from 3.4 million (Uruguay) to 50 million (Colombia) only have 1 residency program. This contrasts with the United States with 87 residency programs and a 328 million population, Canada with 13 programs and a 36.6 million population, and Australia and New Zealand with 53 sites and a 30.3 million population. Proportionally, even Brazil with 31 programs and a 211 million population and Mexico with 7 programs and a 127.6 million population appear quite short-serviced. Considering population growth, the growing incidence of cancer, and current human resource gaps,12 it is clear that the number of residents being trained is not adequate to close the human resource gap in Latin America. Moreover, it is clear that radiation oncology resources need to be improved outside of the major cities to improve access to care. In these marginalized settings, radiation therapy practices do not have academic support and there is no track for an academic career to study patient populations in these areas.

Just how many more residents should be trained in Latin America? The answer to this question is not clear, because there are many factors behind the numbers. For each country, there is a distinct story regarding the number of training programs and trainee positions, and these results should not be interpreted without context. In the case of Mexico, each program traditionally trained 3 to 4 residents per year, but in response to the “human resource gap,” the government increased the number of positions to 13 per year suddenly in 2018, back to 3 to 4 in 2019, and back up to 10 in 2020. Now, many Mexican residents are about to graduate although few job openings exist in the country; many will face the decision of whether to find employment out of country, go unemployed, or look for alternative jobs. Unfortunately, a similar occurrence is happening in many other countries, including Peru, Chile, and Colombia (which temporarily shut down its residency program due to the poor job market), and many radiation oncologists today in Latin America are unemployed or working in non–radiation therapy medical roles.

It is challenging to synergistically coordinate capacity building with human and capital resources. For many countries, to create job openings requires either the purchase of additional equipment to expand the clinic capacity, the construction of new radiation therapy centers, or both. However, these projects are costly and the timelines for these expansions are difficult to predict, thus making it difficult to match the equally complex process of increasing the number of radiation oncology resident trainees.

Also, the number of residents trained per year does not reflect the number of new prospective radiation oncologists per year. It is common for residents to train abroad for their residency training (eg, due to limited spots in their home country) and then attempt to return home after residency by applying for radiation oncologist positions. Furthermore, the predicted retiring workforce is currently unknown. These factors make the job market difficult and deceptively competitive and add to the complexity of trying to match supply and demand with regards to residency training.

Before discussing the structure of existing training programs, a note should be made to describe recent turbulence that has contributed to the number of inactive training programs. Due to the political situation and economic collapse in Venezuela, 5 out of 6 radiation oncology training programs have become inactive. Many radiation oncology professionals are now displaced in other countries.23 The story of Brazil is distinct, with 5 inactive training programs. In the early 2010s after the purchase of 80 linear accelerators, Brazil opened many new programs to match the needs of the country.24 However, quickly built residency programs then faced very poor quality results, resulting in the closure of some programs. Brazil is now trying to standardize training requirements in light of this issue, and the new requirements will include training with modern technology and will replace old requirements from the 1980s (A. Rosa, personal communication, June 2020). Unfortunately, even with new published curriculum structure, there is variability in real life compared with what is written across different programs.

Regarding the reported structures of Latin American programs, 75% include VMAT, 70% SRS, and greater than 50% now include SBRT training. Of note, many residents need to rotate at other clinics to obtain this experience, as only 13% of centers in Latin America possess equipment capable of SRS and SBRT.25 All programs reported training in gynecologic brachytherapy. However, training in other anatomic sites was present in less than 50% of programs, with skin and prostate as the second and third most common sites, respectively. Written materials that exist to read and learn about these topics is not enough. Given the prominent role of VMAT, SRS, SBRT, and prostate brachytherapy as tools for best practice, a significant portion of residents are graduating feeling underprepared for modern practice and the competitive market.

Compared with countries that might satisfy certain training requirements with hours of didactic education, radiation oncology programs in Latin America require month-long external rotations in neighboring specialties, including imaging, medical oncology, surgical oncology, and pathology. There appears to be a consensus with 75% of programs including rotations in all 4 domains. However, a degree of heterogeneity remains between the remaining 25% of programs. In 5 programs, residents do not rotate for surgical oncology. In 2, they do not rotate for medical oncology. In 7, they do not rotate for pathology. Finally, in 2 they do not rotate for imaging. The time spent on each rotation is variable but, in most cases, seems to include 1 to 2 months per domain.

Amid high patient volumes, the popular style of learning is “learn by doing” for residents. The busy clinic environment and lack of staff time for mentorship means that resident learning is often self-guided and outside of the clinic. This is true for radiation oncology as well as other specialties. As an example, residents may be asked to perform interstitial brachytherapy unattended on their first attempt, a situation that may feel unsafe for patients and be unduly stressful for residents. This scenario also does not offer space for feedback, mistakes may be repeated, and in the worst case may go unrecognized. Clearly, this is not the outcome that either residents or attendings desire, but it is a reality for certain settings with limited resources.

Compared with other established international guidelines, the duration of Latin American specialty residency training (mean 3.6 years, plus a 1-year internship) is similar to the United States (4 years, plus a 1-year internship), Europe (4 years, plus a 1-year internship), Canada (5 years), and Australia and New Zealand (5 years). Websites exist to explore U.S., Canadian, and Australian programs26, 27, 28, 29; however, residency-specific reports are lacking for these and all other regions. A recent report by Bibualt et al30 suggests that significant disparities in radiation oncology education exist across Europe. Thus, the challenge of sufficient capacitation is not limited to LMICs, and Latin America is certainly not alone in this struggle.

Future directions

-

1.

Residency training reports for other regions of the world are needed to better understand the current educational landscape. Latin America faces the universal struggle of matching national population needs with real-time improvements in infrastructure and human training. However, by sharing accounts of diverse efforts, we can learn from experience how to improve access to radiation therapy globally and track progress. This is the first report of its kind to set a benchmark for the development of radiation therapy education and training across multiple LMICs.

-

2.

In line with understanding the developing workforce, it is also important to understand the retiring workforce. Unless this is known, it will be a “guessing game” for capacity building.

-

3.

Conversations are needed to understand the hurdles and barriers toward building the necessary parallel aspects of infrastructure (eg, building new centers or expanding existing centers). Then, action is required to identify the stakeholders and discover how to align incentives toward faster progress. This is necessary to keep pace with the escalating demand for cancer care.

Conclusion

An unmet need exists to improve the number, distribution, and quality of radiation oncology education and training programs in Latin America, and further work is needed to establish a solution. Although the quantity of trainees is insufficient to close the current human resource divide, growth is limited by available job openings. On the surface, it seems that training is similar among roughly 75% of programs, while substantial variation exists among other programs. The development of radiation oncology specialists must be improved and modernized to address the escalating demand for cancer care.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: Dr Li and Dr Martinez are volunteer, nonpaid board members of the nonprofit organization Rayos Contra Cancer. All other authors have no disclosures to declare.

All data generated and analyzed during the study are included in this published article.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2022.100898.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Amendola B, Quarneti A, Rosa AA, Sarria G, Amendola M. Perspectives on patient access to radiation oncology services in South America. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2017;27:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer tomorrow. Available at: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 3.Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1153–1186. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lemos LLP, Carvalho de Souza M, Pena Moreira D, et al. Stage at diagnosis and stage-specific survival of breast cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Wahab M, Bourque JM, Pynda Y, et al. Status of radiotherapy resources in Africa: An International Atomic Energy Agency analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e168–e175. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna T. Perez and Brady’s Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2008. Radiation oncology in the developing world; pp. 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zubizarreta EH, Fidarova E, Healy B, Rosenblatt E. Need for radiotherapy in low and middle income countries – the silent crisis continues. Clin Oncol. 2015;27:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmore SNC, Grover S, Bourque JM, et al. Global palliative radiotherapy: A framework to improve access in resource-constrained settings. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8:274–284. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblatt E. Planning national radiotherapy services. Front Oncol. 2014;4:315. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton MB, Jacob S, Shafiq J, et al. Estimating the demand for radiotherapy from the evidence: A review of changes from 2003 to 2012. Radiother Oncol. 2014;112:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fundytus A, Sullivan R, Vanderpuye V, et al. Delivery of global cancer care: An international study of medical oncology workload. J Glob Oncol. 2018;(4):1–11. doi: 10.1200/JGO.17.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmore SNC, Prajogi GB, Rubio JAP, Zubizarreta E. The global radiation oncology workforce in 2030: Estimating physician training needs and proposing solutions to scale up capacit. Appl Rad Oncol. 2019;8(2):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Moraes FY, GN Marta, Hanna SA, et al. Brazil's challenges and opportunities. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2015;92:707–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallegos D, Poitevin Chacón MA, Wright JL. Radiation oncology in Mexico: Toward a unified model. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2018;102:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caicedo-Martinez M, Li B, Gonzalez-Motta A, et al. Radiation oncology in Colombia: An opportunity for improvement in the postconflict era. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2021;109:1142–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Atomic Energy Agency. Radiation protection and safety of radiation sources: International basic safety standards. Available at: https://www.iaea.org/publications/8736/radiation-protection-and-safety-of-radiation-sources-international-basic-safety-standards. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 17.Rosenblatt E, Zubizarreta E, editors. Radiotherapy in Cancer Care: Facing the Global Challenge. International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna, Austria: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksen JG, Beavis AW, Coffey MA, et al. The updated ESTRO core curricula 2011 for clinicians, medical physicists and RTTs in radiotherapy/radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Atomic Energy Agency. IAEA syllabus for the education and training of radiation oncologists. Available at: https://www.iaea.org/publications/8159/iaea-syllabus-for-the-education-and-training-of-radiation-oncologists. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 20.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Radiation oncology program requirements and FAQs. Available at: https://acgme.org/Specialties/Program-Requirements-and-FAQs-and-Applications/pfcatid/22/Radiation%20Oncology. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 21.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Curriculum | RANZCR. Available at: https://www.ranzcr.com/trainees/radiation-oncology-training-program/learning-outcomes-and-handbook. Accessed February 16, 2022.

- 22.United Nations. World population prospects 2019. Available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed December 6, 2021.

- 23.Observatorio Venezolano de la Salud. ¿Qué sucede con el Programa Nacional de Cáncer en Venezuela? Available at: https://www.ovsalud.org/publicaciones/salud/que-sucede-con-el-programa-nacional-de-cancer-envenezuela/. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 24.Sociedade Brasileira de Radioterapia. RT2030. Available at: https://sbradioterapia.com.br/rt2030/. Accessed December 27, 2020.

- 25.Sarría G, Martínez D, Del Castillo R. Establishing radiation therapy GAPs in LATAM, for an optimal cancer care in the next decade. RLA/6/077. Paper presented at: Taking Strategic Actions to Strengthen Capacities in the Diagnostics and Treatment of Cancer With a Comprehensive Approach (ARCAL CXLVIII) May. 20-24, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Society for Radiation Oncology. Association of Residents in Radiation Oncology (ARRO). Available at: https://www.astro.org/Affiliate/ARRO. Accessed July 21, 2021.

- 27.Giuliani M, Gospodarowicz M. Radiation oncology in Canada. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48:22–25. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CaRMS. Program Descriptions - First Iteration. Available at: https://www.carms.ca/match/r-1-main-residency-match/program-descriptions/. Accessed July 21, 2021.

- 29.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Training Sites and Networks | RANZCR. Available at: https://www.ranzcr.com/trainees/radiation-oncology-training-program/training-program. Accessed July 21, 2021.

- 30.Bibault JE, Franco P, Borst GR, et al. Learning radiation oncology in Europe: Results of the ESTRO multidisciplinary survey. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2018;9:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.