Abstract

Background

We conducted a phase II study of the combination of pembrolizumab with capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CAPOX) in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma (BTC) to assess response rate and clinical efficacy. Exploratory objectives included correlative studies of immune marker expression, tumor evolution, and immune infiltration in response to treatment.

Patients and Methods

Adult patients with histologically confirmed BTC were enrolled and received oxaliplatin and pembrolizumab on day 1 of cycles 1-6. Capecitabine was administered orally twice daily as intermittent treatment, with the first dose on day 1 and the last dose on day 14 of cycles 1-6. Starting on cycle 7, pembrolizumab monotherapy was continued until disease progression. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary endpoints were safety, tolerability, feasibility, and response rate. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for PD-L1 and immune infiltrates was analyzed in paired tumor biopsies, as well as bulk transcriptome and exome profiling for five patients and single-cell RNA sequencing for one partial responder.

Results

Eleven patients enrolled, three of whom had received no prior systemic therapy. Treatment was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-related grade 3 or 4 adverse events were lymphocytopenia, anemia, and decreased platelet count. Three patients (27.3%) achieved a partial response, and six (54%) had stable disease. The disease control rate was 81.8%. The median PFS was 4.1 months with a 6-month PFS rate of 45.5%. Molecular profiling suggests qualitative differences in immune infiltration and clonal evolution based on response.

Conclusion

Capecitabine and oxaliplatin in combination with pembrolizumab is tolerable and a potentially effective treatment for refractory advanced BTC. This study highlights a design framework for the precise characterization of individual BTC tumors.

Trial Registration

This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03111732).

Keywords: biliary tract cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, capecitabine, oxaliplatin, pembrolizumab, single-cell sequencing, RNA-sequencing, clonal evolution, PD-L1

This article reports results of a phase II study of the combination of pembrolizumab with capecitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma to assess response rate and clinical efficacy.

Implications for Practice.

Biliary tract carcinoma (BTC) is a rare malignancy with a dismal prognosis. Here, the authors report the results of a phase II clinical trial of pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, in combination with the cytotoxic agents capecitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with advanced BTC, one of the first immunotherapy trials in patients with this diagnosis. The disease control rate for this novel combination compares favorably to other immune checkpoint inhibitor studies, and treatment was well tolerated. Additionally, changes are reported in immune marker expression, tumor evolution, and immune infiltration in response to treatment, providing valuable insight into tumor biology.

Introduction

Biliary tract carcinoma (BTC) encompasses a group of uncommon malignancies originating in the intra- and extrahepatic biliary ductal system and the gallbladder. The incidence and mortality of BTC has increased in recent years.1,2 The current 5-year survival rate in patients with early stage BTC who undergo curative-intent surgery is 30%.3 However, most patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis, resulting in poor prognosis given limited treatment options.4 The current standard of care for metastatic or unresectable BTC is cytotoxic chemotherapy with gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin, based on the ABC-02 trial, in which patients treated with the combination had a superior median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with gemcitabine alone (8.0 vs 5.0 months and 11.7 vs 8.1 months, respectively; P < .001).5

The ABC-02 trial consisted primarily of first-line intervention. For patients who progress following first-line therapy, there is no approved standard-of-care second-line option, and therapy is usually an extrapolation from agents used in pancreatic or other gastrointestinal cancers. Modified FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) has become the most commonly used regimen in the second-line setting, based on the phase III study ABC-06,6 in which patients with advanced BTC who progressed on first-line treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin had a median 12-month OS rate of 25.9% when treated with mFOLFOX vs. 11.4% with no treatment.

Next-generation sequencing has led to breakthroughs in our understanding of the genetic landscape of BTC. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations as well as FGFR fusions form the basis for targeted therapies in BTC.7-9 However, targeted therapeutic agents benefit only a subset of the patient population, as fewer than half of CCA patients have a potentially actionable genetic alteration. In contrast to hepatocellular carcinoma, the clinical data on immunotherapy in BTC are presently limited, and the overall outcome of immunotherapy in BTC is still to be defined.10,11 Furthermore, few studies incorporate biopsy-derived molecular profiles to track tumor evolution and the tumor microenvironment in response to treatment.12

We conducted a phase II study of the combination of an immune-based approach (pembrolizumab) with cytotoxic agents (CAPOX) in patients with advanced BTC. Treatment with anti-PD1 monotherapy has shown minimal efficacy in BTC, but combination therapies are relatively untested. We combined pembrolizumab with a chemotherapeutic backbone that has been used in BTC13 and has been suggested to cause immunogenic cell death, which could potentiate the action of the immune checkpoint inhibitor. This trial also served to evaluate the feasibility of conducting genetic and molecular analysis in paired tumor biopsies and to correlate these characteristics with clinical response in this difficult-to-treat patient population. We obtained paired tumor biopsies from patients immediately prior to treatment and 8 weeks after treatment initiation to allow us to leverage tools such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis, bulk RNA sequencing and whole-exome sequencing (WES),14 and single-cell analysis to improve our understanding of the response of advanced BTC patients to immune checkpoint inhibitors at the cellular and molecular level. Here we describe the clinical results (PFS, RR, and OS) along with a thorough analysis of correlative data. We believe this study provides important information for the design of future correlative studies in patients with hepatobiliary cancers treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Patients and Methods

Primary eligibility criteria were age 18 years or older with histologically confirmed BTC (including intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gallbladder cancer, or ampullary cancer) by the Laboratory of Pathology of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) or histopathological confirmation of carcinoma in the setting of clinical and radiological characteristics which, together with the pathology, were highly suggestive of a diagnosis of BTC. Additional key eligibility criteria included: disease that was not amenable to potentially curative liver transplantation or resection; progression of disease on at least one line of chemotherapy for BTC; or refusal of first-line systemic treatment. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 or 1 (on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater disability); adequate hepatic, renal, and hematological function; at least one focus of measurable metastatic disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1; and at least one focus of metastatic disease amenable to pre- and on-treatment biopsies. The biopsied lesion was not one of the target measurable lesions. Patients were excluded if they had received systemic anticancer therapy or an investigational agent 4 weeks before day 1 or if they received radiotherapy 2 weeks before day 1. Patients eligible for curative resection, those priorly treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors or oxaliplatin, liver transplant recipients, and patients with HIV infection, active hepatitis C or hepatitis B infection, pneumonitis, or brain metastasis were excluded. All patients provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the NCI Institutional Review Board (#17C0082). The ClinicalTrials.gov identifier was: NCT03111732.

Study Design

Patients who satisfied the eligibility criteria were enrolled in the study from June 2017 to February 2020 and received pembrolizumab (200 mg IV) and oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2 IV) on day 1 of cycles 1-6. Pembrolizumab was infused first, and oxaliplatin was given 30 minutes later. Capecitabine at a dose of 750 mg/m2 twice daily was administered orally with the first dose on the evening of day 1 of cycles 1-6 and the last dose the morning of day 14 of cycles 1-6 as intermittent treatment. The cycle length was 3 weeks (consisting of 2 weeks of capecitabine treatment followed by 1 week off). Starting on cycle 7, pembrolizumab was administered alone on day 1 and every 3 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Continuation of treatment after radiographic disease progression was not permitted. A post-treatment follow-up visit for safety occurred 30 days after end of treatment, and patients were followed from start of study until last known date alive (or date of death). Staging was performed by radiographic assessment of contrast enhanced CT scan from cycle 1 day 1 every 9 weeks; objective response was evaluated using the RECIST version 1.1 criteria. Research biopsies of the same lesion were performed pretreatment on study, on day 1 and day 43. Safety and tolerability were assessed from the first dose of study treatment by the incidence of treatment-related adverse events and by severity and type of adverse event per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the PFS based on RECIST version 1.1 assessment. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from the date of consent to the date of first documentation of disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Secondary objectives were safety, tolerability, and feasibility as well as the response rate by RECIST version 1.1 and OS of patients with advanced BTC treated with pembrolizumab in combination with CAPOX. Exploratory objectives aimed to measure changes in programmed cell death receptor ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and immune parameters in the tumors of the patients following the combination treatment.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) slides from baseline and post-treatment tumors from five patients (n = 10), as well as adjacent nontumor tissue from the same slides where available (n = 4). Library preparation was performed using the Agilent SureSelect XT Human All Exon v7 +UTR kit. All samples were sequenced on a single Illumina NovaSeq S2 flowcell (2 × 150 bp).

Reads were trimmed for low-quality bases and adapters removed using Trimmomatic-0.3315 in paired-end mode. Trimmed reads were aligned to the GRCh38.d1.vd1 human reference genome using BWA-MEM (see http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml) mem mapping software (v. 0.7.17).16 All mapped reads from a sample were assigned to a single read group, bam files were coordinate-sorted, and duplicate reads were flagged using Picard tools (v. 2.1.1) and NovoSort (v3.08.02). Following Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (v. 3.8.0) best practices,17,18 indels were realigned, and base quality score recalibration was performed.

Somatic Variant Calling

Tumor-only variant calling was performed using two methods on the recalibrated read alignments. Variants were called using GATK4 MuTect2 with the BadCigar read filter applied; no hard filtering or comparison to population databases was performed. Variants were also called using VarScan (v2.4.3) on Samtools mpileups19-21 with the default parameters used by SuperFreq, with the exception of a samtools mpileup max depth of 10 000 vs 1000.

Clonality Analysis

Clonality analysis was performed for each patient on the baseline and post-treatment tumors using SuperFreq v1.4.222 (mode: exome, hg38). Input for each tumor included WES read alignments generated using GATK best practices (see above) and somatic variants called for each tumor using MuTect2. Eleven HCC and BTC nontumor samples sequenced on the same flow cell and processed identically were used as the reference panel.

Clonal structure at each timepoint for each patient was extracted from the “clones_[patient].tsv” file. Characteristic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number alterations (CNAs) for each clone were extracted from the “[patient]-river.tsv” file.

CCA Driver Mutations

A list of 100 known CCA driver genes was compiled from previous publications: Chaisaingmongkol et al.,23 Farshidfar et al.,24 Ong et al.,25 Jiao et al.,26 Nakamura et al.,27 Jusakul et al.,28 and Wardell et al.29

Bulk Total RNA-seq

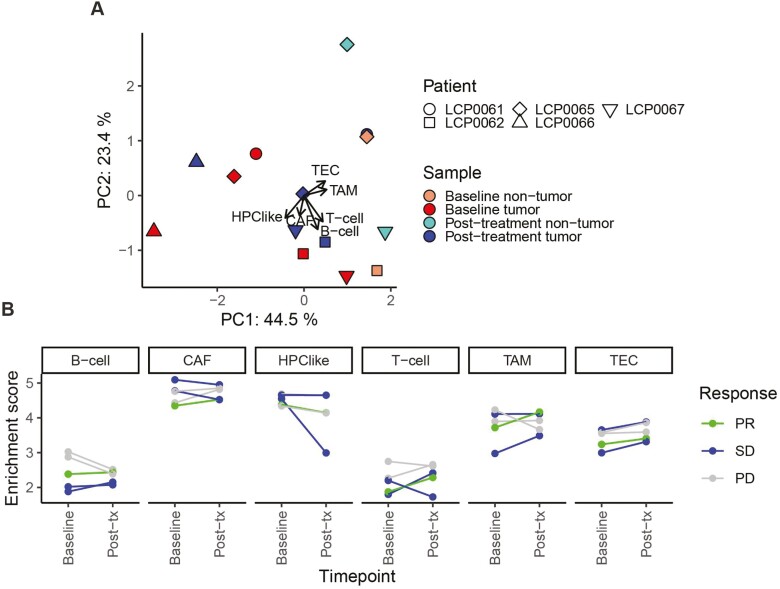

RNA was extracted from FFPE slides from baseline and post-treatment tumors from five patients (n = 10), as well as adjacent nontumor tissue from the same slides where available (n = 4). Libraries were prepared using the NEBnext Ultra Low Input Total Library prep kit. Libraries were sequenced on both a NovaSeq S2 and a NovaSeq S4 flowcell (2 × 150 bp), and data from both flowcells were combined. Reads were trimmed using Cutadapt v1.1830 to remove adapters and low-quality reads before mapping to hg38 using STAR (v. 2.5.2b)31 2-pass alignment. Reads were assigned to a single read-group and duplicates flagged using Picard tools (v.2.17.11). The strandedness of the library was inferred using RSeQC (v. 2.6.4).32 Gene expression was quantified using RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization with the inferred strandedness informing the forward probability (v. 1.3.0).33 Expected gene counts were filtered to remove lowly expressed genes using the limma R package34 (default parameters, samples grouped by timepoint and malignancy), and voom quantile normalization was performed. Fig. 4A and B was generated using the top 3000 most variable genes across all samples. Figure 4B was generated using the ComplexHeatmap package.35

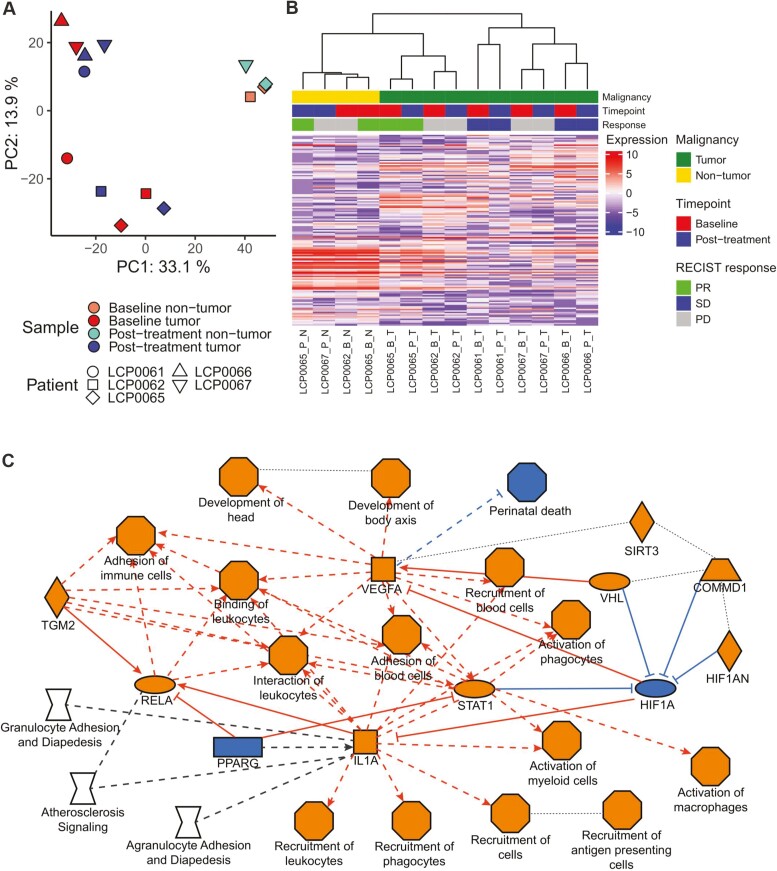

Figure 4.

Transcriptomic response to immunotherapy. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) on samples based on the 3000 most variable genes after voom quantile normalization. Axes indicate the variance explained by each principal component (PC). Shapes represent the patient, and color indicates the sample timepoint and malignancy. The input matrix was scaled and centered prior to PCA. (B) Heatmap of gene expression based on the 3000 most variable genes. Hierarchical clustering based on Pearson correlation on both samples (columns) and genes (rows). Samples are labeled by patient, timepoint (B: baseline, P: post-treatment), and malignancy (T: tumor, N: nontumor). PD: progressive disease; SD: stable disease; PR: partial response. (C) Graphical summary of IPA pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between paired baseline and post-treatment tumors (raw P-value < .01, n = 482), recreated from IPA image. Orange indicates an activated node (positive z-score), blue indicates an inhibited node (negative z-score), gray/no fill indicates effect not predicted. Oval: transcription regulator, square: cytokine, inverted diamond: canonical pathway, octagon: function, diamond: enzyme, trapezoid: transporter, rectangle: ligand-dependent nuclear receptor. Solid lines: direct interactions, dashed lines: indirect interactions, dotted lines: inferred correlation. Edges with no arrowhead indicate interaction or correlation.

Differential Expression

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DESeq2 on the RSEM raw expected counts matrix, rounded to integer values. To identify DEGs between baseline and post-treatment tumors, tumors were treated as paired, and DEGs were identified from the timepoint contrast. DEGs with an absolute logFC > 0 and raw P-value < .01 were uploaded to Qiagen Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, v. 60467501). A Core Analysis (expression analysis, default settings) was performed, and the default Graphical Summary was exported.

single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

The ssGSEA2.0 repo was cloned (https://github.com/broadinstitute/ssGSEA2.0). The TPM normalized gene expression matrix output by RSEM was converted to a Gene Cluster Text file. ssGSEA was performed using the provided CLI script (ssGSEA2.0/ssgsea-cli.R) on three modules:

-

(1)

A custom module generated from six marker gene sets detailed in Ma et al.36Supplementary Figure S1. All gene sets were processed regardless of the number of constituent genes. All genes were included in the GCT file.

-

(2)

The MSigDB c8 module (cell-type signature gene sets; GMT file downloaded from the MSigDB website), restricted to 31 gene sets defined in Aizarani et al.37

-

(3)

Fifty-one gene sets derived from four publications from Aran et al.38 Additional file 5 (“The 53 previously published cell type gene signatures.”), restricted to four CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets. Gene sets with <3 genes in the GCT were excluded.

Gene set enrichment scores, P-values, and FDR-corrected P-values were extracted from the “-combined.gct” output file.

Single-Cell RNA-seq

Single-cell data were generated using droplet-based scRNA-seq on fresh-frozen tissue in a previous study.39 Biopsies used for single-cell analysis were collected on the same date as those used for bulk analysis. Normalized gene expression profiles and cell type assignments are available under Gene Expression Omnibus: GSE151530. Variable gene selection, principal component analysis, and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis were carried out using the R Seurat package (version 3.1.2). Malignant cells were identified by inferring chromosomal copy number variations. Nonmalignant cells were annotated based on gene sets used in 36. Malignant/T-cell–specific genes were determined by differential gene expression analysis with thresholds of adjusted P-value < .05 and average log fold change > 0.5. Heatmaps were generated using the R ComplexHeatmap package (version 2.2.0).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor tissue was processed by the Department of Pathology at the NCI. Tumor slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, anti-PD-L1, anti-CD3, and anti-CD8 after fixation with formalin and being embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemistry was evaluated semiquantitatively by a hepatopathologist (D.K.).

Software

Visualization was performed using custom scripts in R (v. 4.0.2). R packages used include: circlize (v0.4.11), ComplexHeatmap (v2.4.3), ggplot2 (v3.3.3), gridExtra (v2.3), openxlsx (v4.2.3), plyr (v1.8.6), RColorBrewer (v1.1.2), reshape2 (v1.4.4), limma (v3.44.3), edgeR (v3.30.3), ggrepel (v0.9.1), and DESeq2 (v1.28.1).

Statistical Methods

The primary objective of this study was to determine in a preliminary, limited-size trial whether pembrolizumab in combination with CAPOX is associated with a 5-month progression-free probability, which exceeds 25% when used to treat patients with BTC. In patients with similar eligibility requirements, the median PFS in BTC is 2.5 months. This translates to 25% without progressive disease (PD) at 5 months following an exponential failure model. Based on these results, it was considered useful to demonstrate whether pembrolizumab in combination with CAPOX was able to be associated with a median PFS of 5 months, which would correspond to 50% of patients having stable disease (SD) at 5 months. The trial was conducted using a two-stage optimal design. With α = 0.10 and β = 0.10 as acceptable error probabilities, the trial targeted 50% as the desirable proportion of patients who are still without progression at the 5-month evaluation (p1 = 0.50) and was to be considered inadequate if only a fraction consistent with 20% are without progression by the same evaluation time (p0 = 0.20). The first stage of the trial would require three of 10 patients to be without progression by 5 months in order to enroll to a total of 17 patients; six or more without progression by 5 months would justify further investigation.

In addition to evaluation of the proportion of patients that are progression-free at 5 months, the PFS was analyzed via Kaplan-Meier curve, considering progression or death as a failure. Overall survival was also evaluated using a Kaplan-Meier curve. The primary objective of the study was determined according to published literature; pooled analysis of CCA patients who have received second-line chemotherapy have a median PFS of 2.5 months and a median OS of 5.9 months. We aimed to double the PFS reported in BTC patients receiving second-line therapy.40

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between June 2017 and February 2020, a total of 11 patients with advanced BTC were enrolled onto the study. The protocol was closed after the first stage due to slow accrual, and an alternative analysis was performed. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median age of the population was 67 years (range 51 to 81), and 55% of patients were female. Seven (64%) of 11 patients had an ECOG performance status score of 0, with the remaining having a score of 1. More than one third of patients (36%) had metastatic disease, and 54% of patients had received two or more systemic chemotherapy treatments before enrolling on study. Most patients had received treatment with platinum-based cytotoxic regimens before study, most commonly gemcitabine and cisplatin; three patients were chemotherapy naïve. Most patients had intrahepatic CCA (73%), and three patients had cancer of the gallbladder. One patient had a history of Hepatitis B infection. The average number of weeks between diagnosis of BTC and consent on study was 57.6 weeks (range 4.4 to 182.9 weeks). Only one patient had a therapeutically relevant genetic alteration: an FGFR fusion. All patients were MMR proficient.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median | 67 (51-81) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 6 (55%) |

| Male | 5 (45%) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 7 (64%) |

| 1 | 4 (36%) |

| Metastatic disease | |

| Yes | 4 (36%) |

| No | 7 (64%) |

| Number of previous systemic therapies | |

| None | 3 (27%) |

| 1 | 4 (36%) |

| 2 | 2 (18%) |

| 3 or more | 2 (18%) |

| Previous surgery | 2 (18%) |

| Previous radiotherapy | 2 (18%) |

| Primary tumor location | |

| Intrahepatic | 8 (73%) |

| Gallbladder | 3 (27%) |

| History of hepatitis | |

| Hepatitis B | 1 (9%) |

| Hepatitis C | 0 (0%) |

| Sites of disease | |

| Liver | 11 (100%) |

| Lymph nodes | 10 (91%) |

| Lung | 1(9%) |

| Presence of therapeutically | 1 (9%) |

| Relevant genetic alterationsa | |

FGFR, IDH1 and 2, NTRK, BRAF.

Patients completed a median of 6.5 cycles (range 5.5-8.5) of treatment on study. Patients with PD received a mean of 5.5 cycles of treatment, those with SD received a mean of 6.5 cycles, and patients with a partial response (PR) to treatment received a mean of 8.5 cycles of therapy. The patient who remained on study for the longest amount of time had SD and remained on study for 7.7 months (Fig. 1A). The median potential follow-up for the enrolled patients was 34.8 months. The reason for treatment discontinuation in all patients was radiologically confirmed disease progression.

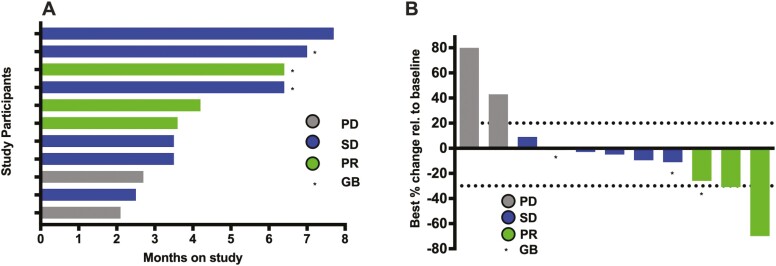

Figure 1.

Efficacy data from the study population. (A) Swimmer plot showing time on study and response status. Months on study; colored bars indicate confirmed responses assessed by RECIST 1.1. (B) Waterfall plot of all radiographic responses. Tumor responses were measured at regular intervals, and values show the best fractional change of the sum of longest diameters from the baseline measurements of each measurable tumor. Colored bars indicate confirmed responses assessed by RECIST 1.1. RECIST 1.1 = response evaluation criteria in solid tumors version 1.1. PD = progressive disease. SD = stable disease. PR = partial response. GB = Gallbladder tumor.

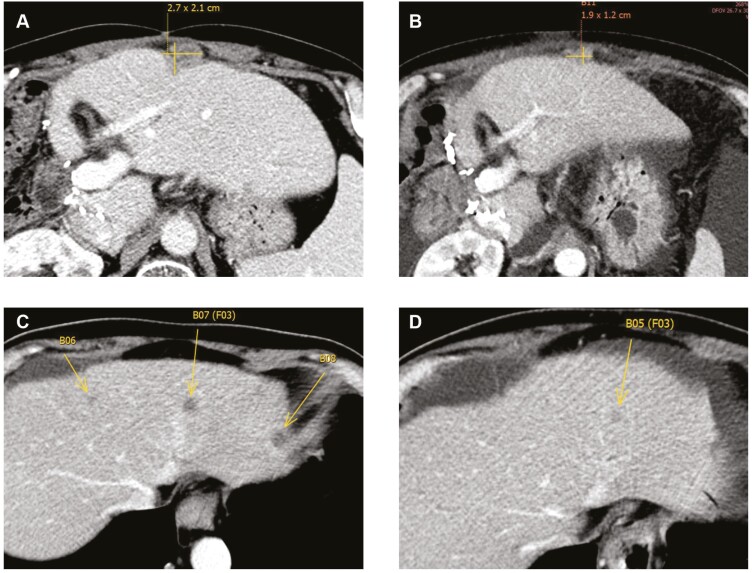

All patients were evaluable for response. Two patients (18.2%) had PD as best treatment response, 6 (54.6%) patients had SD, and 3 (27.3%) patients had a PR per RECIST version 1.1. Among the eight patients that underwent treatment prior to enrolling on study, four had SD and two had a PR. Three patients were treatment naïve; two had SD and one had a PR. Among the three patients who had gallbladder cancer, one had a PR and two had SD. The overall disease control rate, which included PR and SD, was 81.8 % (Figure 1B). The patient with the best response had a reduction of 70% of the measurable lesions in a 3-month period. Fig. 2 shows representative computed tomography41 images of the abdomen and pelvis from a patient with a 31% PR to treatment.

Figure 2.

Representative CT images of the abdomen and pelvis baseline and on treatment of two patients presenting with a partial response to treatment. (A, B) Perihepatic lymph node decreasing in size from ~2.7 to 1.9 cm. (C, D) Decrease in number and size of intrahepatic tumor lesions.

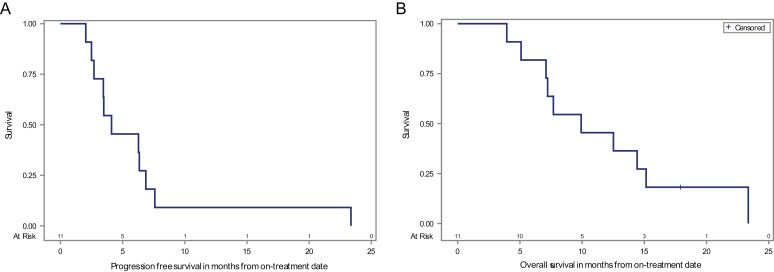

The median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI: 2.5-6.9 months), the 6-month PFS probability was 45.5% (95% CI: 16.7-70.7%), and the 12-month PFS was 9.1% (95% CI: 0.5-33.3%; Fig. 3A). Five of 11 patients progressed beyond 5 months (45%; 95% CI: 16.8-76.6%). The median OS was 9.9 months (95% CI: 5.1-15.1 months), with a 6-month OS percentage of 81.8% (95% CI: 44.7-95.1%), a 12-month OS of 45.5% (95% CI: 16.7-70.7%), and an 18-month OS of 18.2% (95% CI: 2.9-44.2%; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Patient survival with the combination of pembrolizumab with chemotherapy. (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival; median PFS: 4.1 months (95% CI: 2.5-6.9 months); 6-month PFS: 45.5% (95% CI: 16.7-70.7%); 12-month PFS: 9.1% (95% CI: 0.5-33.3 %). B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS); median OS: 9.9 months (95% CI: 5.1-15.1 months); 6 months OS: 81.8% (95% CI: 44.7-95.1%); 12 months OS: 45.5% (95% CI: 16.7-70.7%); 18 months OS:18.2% (95% CI: 2.9-44.2%).

Safety

The most common treatment-related toxicities of all grades for CAPOX in combination with pembrolizumab included fatigue and nausea. The most common grade 3 and 4 adverse events were decreased lymphocyte counts (64%), anemia (36%), decreased platelet count (27%), and hyponatremia (27%; Table 2). There were no immune mediated adverse events or treatment-related deaths on study.

Table 2.

Grade 3-4 treatment related adverse events

| Adverse event | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Decreased lymphocyte count | 7 (64%) |

| Decreased neutrophil count | 2 (18%) |

| Anemia | 4 (36%) |

| Decreased platelet count | 3 (27%) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 2 (18%) |

| Increased alkaline phosphatase | 1 (9%) |

| Increased alanine aminotransferase | 1 (9%) |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase | 1 (9%) |

| Increased amylase | 2 (18%) |

| Increased lipase | 1 (9%) |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (27%) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 (18%) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (9%) |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (9%) |

Immune Correlatives

Pre-treatment biopsies from five patients and four on-treatment biopsies were analyzed (Table 3). Two of the pretreatment biopsies were negative for PD-L1, while the other three biopsies were positive for PD-L1, including one 1-5% positive, one 10-15% positive, and one 20% positive. The two patients with PD-L1-negative tumor biopsies at baseline went on to have SD and a PR as the best treatment response on study. The patient with a biopsy 1-5% positive for PD-L1 had a PR, the patient with a biopsy 10-15% positive for PD-L1 had PD, and the patient with a pretreatment tumor biopsy 20% positive for PD-L1 had SD as best response. The pretreatment tumor biopsy that was 20% positive for PD-L1 also showed CD3+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration, whereas tumor biopsies that were negative for PD-L1 did not (Supplementary Figure S1 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Immunohistochemistry of tumor samples.

| Patient | Best response | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PR | PD-L1 | Negative | NA |

| CD3 | Negative | NA | ||

| CD8 | Negative | NA | ||

| 2 | PD | PD-L1 | NA | 1% |

| CD3 | NA | NEGATIVE | ||

| CD8 | NA | negative | ||

| 3 | SD | PD-L1 | 20% | NA |

| CD3 | +++ | NA | ||

| CD8 | +++ | NA | ||

| 4 | PR | PD-L1 | 1-5% | Negative |

| CD3 | Negative | Negative | ||

| CD8 | Negative | Negative | ||

| 5 | PD | PD-L1 | 10-15% | 1% |

| CD3 | ++ | Negative | ||

| CD8 | Negative | Negative | ||

| 6 | SD | PD-L1 | NA | Negative |

| CD3 | NA | Negative | ||

| CD8 | NA | Negative | ||

| 7 | SD | PD-L1 | Negative | NA |

| CD3 | Negative | NA | ||

| CD8 | Negative | NA |

SD, stable disease; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; CD3, cluster of differentiation 3; CD8, CD8+ T-cell infiltration; NA, not available.

Transcriptome and Exome Profiling

To further investigate the molecular response to the treatment regimen, we performed WES and total RNA-seq on baseline and post-treatment tumors from five CCA patients, as well as adjacent nontumor tissue from two baseline and two post-treatment biopsies. Patients included two with PD, two with SD, and a PR. Based on the overall transcriptome, biopsies primarily cluster by patient rather than by treatment status (Fig. 4A and B). Additionally, despite their physical proximity to the tumors, adjacent nontumor tissue exhibits a distinct transcriptomic profile (Fig. 4B). Although the sample size is limited, these results recapitulate those observed with single cell data36 and confirm that sampling bias does not outweigh patient-specific gene expression programs. Interestingly, patients do not cluster by clinical response (Fig. 4B).

Given the small sample size and variable clinical response, as well as anticipated inter-individual variability, identifying gene pathways that change consistently in response to treatment was unlikely. However, although few genes are significantly up- or downregulated post-treatment, the top candidates are enriched in immune-related pathways, indicating increased recruitment and activation of immune cells such as leukocytes, macrophages, and APCs (Fig. 4C). This is consistent with the expected mechanism of immunotherapy but suggests that immune response varies across patients.

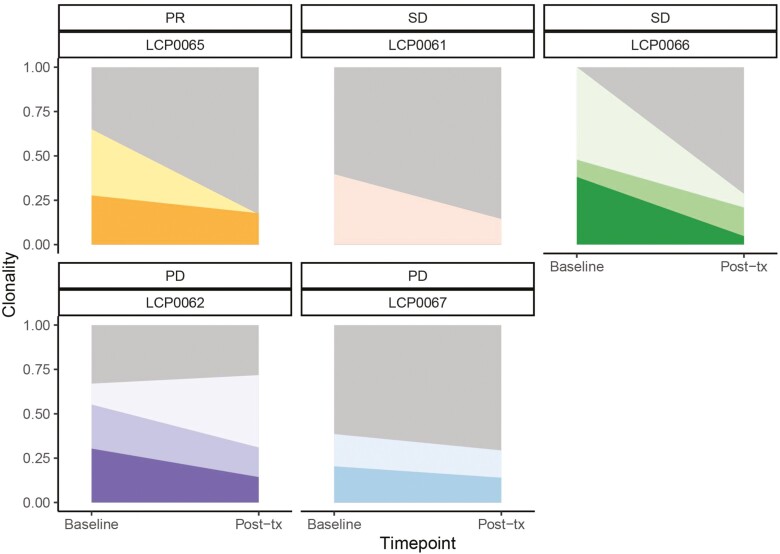

Next, we investigated tumor evolution trajectories in response to treatment using SuperFreq (Fig. 5). Compared to patients with PD, the partial responder and those with SD exhibit a decrease in the clonality of the dominant baseline tumor clones using raw variants called with MuTect2. This may reflect an overall reduction in tumor burden and/or differentiation of the tumor into a more complex clonal structure that is more difficult to track. In contrast, patients with a worse outcome maintain the dominant clone after treatment, with LCP0062 exhibiting expansion of a parent clone.

Figure 5.

SuperFreq clonality analysis by patient using MuTect2 raw variants. River plots display the clonality of the germline clone (gray) and tumor clones in baseline and post-treatment tumors. Darker clones are subclones of lighter parent subclones, and all are subclones of the germline clone. PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Identifying driver mutations is hindered by the use of FFPE samples, which have a high false-positive somatic variant rate. Nevertheless, we identified 19 SNVs within known CCA driver genes linked to the tumor clones, eight of which are frameshift or nonsynonymous mutations (Supplementary Table S1, Methods). Although none of the SNVs is shared between patients, there are three cases in which the same gene is affected in two individuals. Both the LCP0061 (SD) clone and LCP0062 (PD) subclone 2 have a frameshift mutation in TP53. In addition, the two patients with PD (LCP0062 and LCP0067) both have SNVs within PRKDC and NF1, but in both cases, only one is nonsynonymous. In contrast, the partial responder (LCP0065) has only a synonymous mutation in RB1 and a 3’UTR SNV in NF2, both in the parent tumor clone that decreases in response to treatment.

In addition to variants generated using MuTect2, we repeated the clonality analysis using variants called by VarScan (Supplementary Figure S2). Despite similar numbers of input variants, several additional clones and subclones were identified in this model, and the trend of decreasing clonality associated with SD did not hold. This discrepancy is likely due to VarScan calling more germline variants with <25% VAF, leading to slight differences in the identified CNAs. However, the errors associated with the clonality estimates were higher using VarScan, though not significantly, particularly for LCP0066. Additionally, the patient with a PR (LCP0065) still exhibited a pattern of decreasing overall tumor burden with one maintained clone, and 17 of the 19 driver SNVs identified using MuTect2 were also identified using VarScan, though sometimes linked to different clones.

For a more fine-grained analysis of the immune response to treatment, we calculated enrichment scores for six cell types36 in each of the baseline and post-treatment tumors. Interestingly, the tumor trajectory based on the enrichment scores appears qualitatively different based on clinical response. For the patients with PD, post-treatment tumors cluster with baseline tumors and nontumor samples to the bottom right of PC1/2 (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the post-treatment tumors for the PR and SD patients exhibit a greater change in the direction of the tumor-associated endothelial cell (TEC) and tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) loadings. The raw enrichment scores confirm that PR and SD tumors exhibit an average slight increase in TAMs post-treatment, while PD tumors exhibit an average decrease (Fig. 6B). This pattern is more striking for B cells. In contrast, TECs exhibit a consistent increase across all patients regardless of clinical response.

Figure 6.

Immune infiltration using ssGSEA on six cell types with gene sets defined in Ma et al.36 (A) Biplot based on ssGSEA enrichment scores, displaying samples in PC space (points) and loadings for each gene set (arrows). Axes indicate the variance explained by each PC. Shapes represent the patient, and color indicates the sample timepoint and malignancy. The input matrix was scaled and centered prior to PCA. (B) Enrichment scores for each cell type in baseline and post-treatment tumors, colored by patient response. PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; TEC, tumor-associated endothelial cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; HPC, hepatic progenitor cell.

These results are confirmed by additional gene subsets, including liver cell populations derived from single cell analysis (Supplementary Figure S3).37 Resident B-cells (C22, C38) and NK NKT cells (C3, C5) all exhibit a divergent pattern by clinical response. In contrast, subsets of Kupffer cells (C31), MVECs (micro-vascular endothelial cells; C10, C29), and LSECs (liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; C9, C13, C20) increase post-treatment regardless of clinical response, while EPCAM+ bile duct cells (C39) decrease. As the combined T-cell population did not exhibit a consistent pattern in Fig. 6B, we also calculated the enrichment of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets in the tumors (Supplementary Figure S4).38 Even at a finer resolution, T-cell infiltration levels do not correlate with clinical response. This is consistent with the IHC results, in which an increase in PD-L1 expression and T-cell infiltration was inconsistent with patient outcome. In addition, the results in Supplementary Figure S4 are dependent on the gene signature definition, suggesting that future analyses should focus on more specific subsets of T cells.

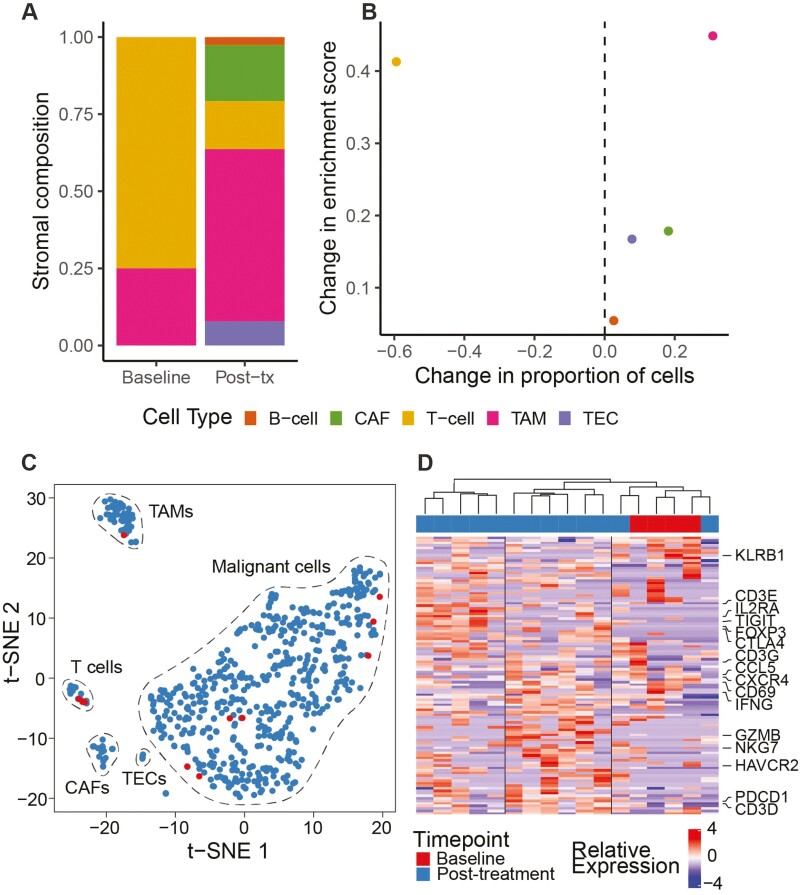

Finally, we confirmed the observed immune response in the partial responder using single-cell RNA-seq (Supplementary Figure S5A). The tumor undergoes an increase in TAMs post-treatment (Fig. 7A), which recapitulates the increase in ssGSEA enrichment score for that cell type observed using bulk RNA-seq (Fig. 7B). We further investigated changes in malignant and T-cell subsets post-treatment. Although the baseline tumor had few sampled malignant cells, they cluster with post-treatment malignant cells, indicating a stable tumor population (Fig. 7C; Supplementary Figure S5B). In contrast, the T cells form three major clusters based on gene expression (Fig. 7D). These include a KLRB1+ T-cell population that dominates the baseline tumor, as well as cytotoxic- and regulatory-like populations whose presence increases post-treatment. These results further suggest that single-cell analysis should be performed, and finer subsets of immune cells investigated in future studies.

Figure 7.

Cellular composition of tumors from a partial responder (LCP0065) before and after treatment using single cell transcriptomics. (A) Stromal cell composition of tumors based on normalized cell type assignments. Baseline, n = 4 cells; post-treatment, n = 77 cells. (B) Change in stromal cell composition after treatment based on single cell transcriptomics or ssGSEA-based enrichment scores using gene sets from Ma et al.36 (C) t-SNE plot of all single cells in the tumor cell communities (n = 598). Cells are colored by sampling timepoint (legend below D). (D) Hierarchical clustering of T cells (n = 17) using T-cell-specific genes. Columns represent cells and are colored by sampling timepoint. Adjusted P-value <.05 and average log fold change >0.5 were applied to generate T-cell-specific genes.

Discussion

Immunotherapy has changed the way we treat many patients with solid cancers, but little is known on its efficacy in BTC.42,43 We conducted a phase II clinical trial in patients with BTC, not only to study the efficacy and safety of chemotherapy in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors in this patient population but also to promote the implementation of thorough correlative studies. Despite limited clinical efficacy, within a heterogenous group of patients, we collected clinical and molecular information that will help design future studies. Patients with advanced and largely chemo refractory BTC who received treatment with CAPOX and pembrolizumab had a disease control rate (DCR) of 81.8%, with 54.6% of patients experiencing SD, and 27.3% having a PR as the best response to treatment on study. The median PFS was 4.1 months (95% CI 2.5-6.9 months), five of 11 patients progressed after more than 6 months on trial, the median OS was 9.9 months (95% CI: 5.1-15.1 months), and the 6-month OS probability was 81.8% (95% CI: 44.7-95.1%).

Our results compare favorably to three other studies conducted in the US, Japan, and Asia testing anti-PD1 (pembrolizumab or nivolumab) and anti-PD-L1 (durvalumab) immune checkpoint inhibitors, which resulted in maximum disease control rates of 60%,44-46 as well as our own protocol, in which we tested anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4 (tremelimumab) in combination with microwave ablation in patients with BTC.10 Chemotherapy is used in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors because preliminary data suggest that cell death secondary to chemotoxic agents may result in mechanisms that unleash effective immunity against malignant cells that were originally intrinsically resistant.47 A phase II study conducted in Japan included 34 patients treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin plus nivolumab in the first-line setting. The median OS was 15.4 months, median PFS was 4.2 months, and 33.4% of patients had an objective response to treatment.44 Apart from combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy, there are also early reports from two studies combining anti-PD1 with ramucirumab or lenvatinib. DCRs of 40% and 78% were reported, respectively.48,49 In summary, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy either alone or in combination has demonstrated moderate efficacy in BTC.

Among the patients in this study, three had gallbladder cancer; this may have contributed to the favorable results seen. A subgroup analysis of a study treating patients with advanced biliary tract cancer with the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab showed a seemingly better response to immunotherapy in patients who had gallbladder cancer when compared to other BTC.50

Correlative studies within immune checkpoint therapy trials are performed to better understand why a treatment works or does not work and to potentially identify biomarkers which can be used to predict response. The most common biomarkers include PD-L1 expression on tumor biopsies and tumor mutation burden. Here, we included IHC for PD-L1 and CD3+ and CD8+ T cells as well as deep molecular analysis of tumor biopsies, including single-cell analysis on select samples. Programmed cell death receptor ligand 1 status has limitations as a predictive response biomarker to immunotherapy in BTC. The reported incidence of PD-L1 positivity in BTC is between 49% and 94%, which is much higher than we have seen in our patients. Furthermore, PD-L1 expression has been associated with a worse outcome.51-53

Unexpectedly, radiological response of the patients in our study did not correlate with PD-L1 tumor expression50,54, although tumor biopsies with higher PD-L1 expression also had an increased amount of CD3+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration when compared with PD-L1 negative tumor samples. Of the evaluable biopsies, two patients (18%) had PD-L1 negative tumors; one of these patients had a PR and the other SD. On the other hand, one patient with a PD-L1 10-19% positive tumor did not evidence effectiveness of therapy. It is not clear why patients with less PD-L1 expression would benefit more from immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy; the small sample size of the study may be contributing to this finding and more tumor samples are clearly needed to confirm this finding.

Although an increase in infiltrating CD8+ T cells recruited to the tumor site in the presence of immunomodulation through immune checkpoint inhibition may be expected, the sample size in our study is too small to be representative of all BTC tumors. The frequency of tumor infiltration by specific immune cells in BTC and their association with outcomes has been described: CD4+ and CD8+ positive T-cells infiltrate in 30–51% of cases and this has been associated with reduced metastases and an increase in survival (especially in extrahepatic CCA).55-57Because our patient population is limited to 11 patients some of our findings may be due to chance. The CD4+ and CD8+ analysis conducted does not allow further conclusions nor addresses the possibility of CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and likely inclusion of CD4+ T cells as regulatory cells.

To delve deeper into the molecular response to immunotherapy, we profiled clonal evolution and gene expression in baseline and post-treatment samples from five CCA patients. We observed an increased signature of immune recruitment and activation after treatment averaged across all patients. However, changes in immune composition were variable, with some immune subsets qualitatively tracking with patient response. For instance, the partial responder and those with SD, but not patients with PD, have an increased enrichment of B cells and TAMs post-treatment, which was confirmed by single-cell analysis of the partial responder. We also observed qualitative differences in the clonal trajectory of tumors post-treatment based on patient response, although these are dependent on the somatic variant calling method.

These results suggest the potential for molecular characterization to facilitate treatment of BTC. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown great promise in a subset of patients, and identifying factors that correlate with clinical response may inform adjuvant treatments to improve response rates.58,59 However, due to the small size and heterogeneity of this patient population, the results of this study are highly qualitative and cannot be used to make definitive conclusions. Molecular analyses may also be affected by tumor purity, which is highly variable across the source tissues; additionally, some but not all samples were macrodissected prior to sequencing. Furthermore, reliance on FFPE samples limits our ability to accurately identify driver mutations, although the overall immune response was confirmed in the partial responder using single cell sequencing from frozen samples collected concurrently. Future studies should include comparisons of FFPE and fresh-frozen tissue.

The Keynote-028 study of PD-L1 positive patients treated with pembrolizumab60 found that tumor mutation burden, PD-L1 expression, and a gene signature characteristic of T-cell activation in the tumor microenvironment were predictive of response to pembrolizumab in several tumor types. Although we find little correlation between PD-L1 expression and clinical response, our single-cell results suggest alterations in the profile of tumor-associated T-cells post-treatment.

Despite the challenging nature of BTC for research efforts, the pathogenesis and complex molecular landscape of BTC is being increasingly investigated. Tumor genome sequencing has identified targetable genomic abnormalities, which have resulted in novel targeted therapies. There continues to be an unmet need to comprehensively characterize BTC at the molecular level to further develop targeted therapies to actionable genetic abnormalities. Furthermore, molecular profiling will play an important role in the future in determining the specific prognosis of individual patients. Our study hopes to advance understanding of BTC in the advanced and refractory setting.

Limitations of this trial include a lack of a control group and a small number of heterogenous patients. Additionally, although most enrolled patients had iCCA, the inclusion of patients with GBC could have complicated the data analysis, since these tumors may have different characteristics and prognosis. Despite these limitations, the observed DCR was a benefit seen across all tumor groups. The encouraging anti-tumor activity seen with the combination treatment of pembrolizumab and CAPOX in our study evidences the potential benefit of chemotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab in the treatment of advanced BTC. Furthermore, studies are needed to elucidate the exact role of immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy in advanced BTC. More importantly, our study features a framework in which to identify potential biomarkers, including clinical, pathologic, and molecular features. This entails a paradigm shift to expedite the acquisition of biomarker knowledge, including at the cellular level, to personalize and optimize treatment in patients with advanced BTC who currently face a grim prognosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: T.F.G. and X.W.W. are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI [ZIA BC 011343, ZIA BC 010877, ZIA BC 011870]. The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between NCI and Merck. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, data collection, and analysis.

Contributor Information

Cecilia Monge, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Erica C Pehrsson, Liver Cancer Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; CCR Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Advanced Biomedical Computational Science, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD, USA.

Changqing Xie, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Austin G Duffy, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Donna Mabry, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Bradford J Wood, Center for Interventional Oncology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

David E Kleiner, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Seth M Steinberg, Biostatistics and Data Management Section, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

William D Figg, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Bernadette Redd, Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Anuradha Budhu, Liver Cancer Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Sophie Wang, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Mayank Tandon, CCR Collaborative Bioinformatics Resource, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Advanced Biomedical Computational Science, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD, USA.

Lichun Ma, Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Xin Wei Wang, Liver Cancer Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Tim F Greten, Gastrointestinal Malignancies Section, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; Liver Cancer Program, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G. Provision of study material/patients: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G. Collection and/or assembly of data: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G. Data analysis and interpretation: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G. Manuscript writing: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G. Final approval of manuscript: C.M., E.C.P., C.X., A.G. D., D.M., B.J.W., D.E.K., S.M.S., W.D.F., B.R., A.B., S.W., M.T., L.M., X.W.W., T.F.G.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Carioli G, et al. Global trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2019;71(1):104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mukkamalla SKR, Naseri HM, Kim BM, Katz SC, Armenio VA. Trends in incidence and factors affecting survival of patients with cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(4):370-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mavros MN, Economopoulos KP, Alexiou VG, Pawlik TM. Treatment and prognosis for patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):565-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morizane C, Ueno M, Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Ishii H, Furuse J. New developments in systemic therapy for advanced biliary tract cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2018;48(8):703-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. ; ABC-02 Trial Investigators . Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1273-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lamarca A, Palmer DH, Wasan HS, et al. ABC-06 | A randomised phase III, multi-centre, open-label study of active symptom control (ASC) alone or ASC with oxaliplatin/ 5-FU chemotherapy (ASC+mFOLFOX) for patients (pts) with locally advanced/ metastatic biliary tract cancers (ABC) previously-treated with cisplatin/gemcitabine (CisGem) chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):4003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lamarca A, Barriuso J, McNamara MG, Valle JW. Molecular targeted therapies: ready for “prime time” in biliary tract cancer. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):170-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma - evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):95-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valle JW, Lamarca A, Goyal L, Barriuso J, Zhu AX. New Horizons for precision medicine in biliary tract cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(9):943-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xie C, Duffy AG, Mabry-Hrones D, et al. Tremelimumab in combination with microwave ablation in patients with refractory biliary tract cancer. Hepatology. 2019;69(5):2048-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Santana-Davila R, Bhatia S, Chow LQ. Harnessing the immune system as a therapeutic tool in virus-associated cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duffy AG, Makarova-Rusher OV, Greten TF. The case for immune-based approaches in biliary tract carcinoma. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1785-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. The secret ally: immunostimulation by anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(3):215-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kurtz DM, Esfahani MS, Scherer F, et al. Dynamic risk profiling using serial tumor biomarkers for personalized outcome prediction. Cell. 2019;178(3):699-713.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(17):2283-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. ; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flensburg C, Sargeant T, Oshlack A, Majewski IJ. SuperFreq: integrated mutation detection and clonal tracking in cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2020;16(2):e1007603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaisaingmongkol J, Budhu A, Dang H, et al. ; TIGER-LC Consortium . Common Molecular subtypes among Asian hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(1):57-70.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farshidfar F, Zheng S, Gingras MC, et al. ; Cancer Genome Atlas Network . Integrative genomic analysis of cholangiocarcinoma identifies distinct IDH-Mutant Molecular Profiles. Cell Rep. 2017;18(11):2780-2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ong CK, Subimerb C, Pairojkul C, et al. Exome sequencing of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):690-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiao Y, Pawlik TM, Anders RA, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1470-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47(9):1003-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jusakul A, Cutcutache I, Yong CH, et al. Whole-genome and epigenomic landscapes of etiologically distinct subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(10):1116-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wardell CP, Fujita M, Yamada T, et al. Genomic characterization of biliary tract cancers identifies driver genes and predisposing mutations. J Hepatol. 2018;68(5):959-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnetjournal. 2011;17(1):10-12. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang L, Wang S, Li W. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(16):2184-2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(18):2847-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ma L, Hernandez MO, Zhao Y, et al. Tumor cell biodiversity drives microenvironmental reprogramming in liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(4):418-430.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aizarani N, Saviano A, Sagar , et al. A human liver cell atlas reveals heterogeneity and epithelial progenitors. Nature. 2019;572(7768):199-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aran D, Hu Z, Butte AJ. xCell: digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ma L, Wang L, Khatib SA, et al. Single-cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;75(6):1397-1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ulahannan SV, Rahma OE, Duffy AG, et al. Identification of active chemotherapy regimens in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a review of chemotherapy trials in the past two decades. Hepat Oncol. 2015;2(1):39-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ducreux M, Van Cutsem E, Van Laethem JL, et al. ; EORTC Gastro Intestinal Tract Cancer Group . A randomised phase II trial of weekly high-dose 5-fluorouracil with and without folinic acid and cisplatin in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma: results of the 40955 EORTC trial. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(3):398-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. ; KEYNOTE-001 Investigators . Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sul J, Blumenthal GM, Jiang X, He K, Keegan P, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer whose tumors express programmed death-ligand 1. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):643-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ueno M, Ikeda M, Morizane C, et al. Nivolumab alone or in combination with cisplatin plus gemcitabine in Japanese patients with unresectable or recurrent biliary tract cancer: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(8):611-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim R, Kim D, Alese O, Li D, El-Rayes B, Shah N, et al. A Phase II multi institutional study of nivolumab in patients with advanced refractory biliary tract cancers (BTC). Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl 5):v103. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jakubowski CD, Azad NS. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in biliary tract cancer (cholangiocarcinoma). Chin Clin Oncol. 2020;9(1):2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salas-Benito D, Pérez-Gracia JL, Ponz-Sarvisé M, et al. Paradigms on Immunotherapy Combinations with Chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(6):1353-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lin J, Yang X, Long J, et al. Pembrolizumab combined with lenvatinib as non-first-line therapy in patients with refractory biliary tract carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020;9(4):414-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arkenau HT, Martin-Liberal J, Calvo E, et al. Ramucirumab plus pembrolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer: nonrandomized, open-label, phase I trial (JVDF). Oncologist. 2018;23(12):1407-e136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klein O, Kee D, Nagrial A, et al. Evaluation of combination nivolumab and ipilimumab immunotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers: subgroup analysis of a phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1405-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sabbatino F, Villani V, Yearley JH, et al. PD-L1 and HLA class I antigen expression and clinical course of the disease in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(2):470-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fontugne J, Augustin J, Pujals A, et al. PD-L1 expression in perihilar and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):24644-24651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gani F, Nagarajan N, Kim Y, et al. Program death 1 immune checkpoint and tumor microenvironment: implications for patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(8):2610-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ahn S, Lee JC, Shin DW, Kim J, Hwang JH. High PD-L1 expression is associated with therapeutic response to pembrolizumab in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Marks EI, Yee NS. Immunotherapeutic approaches in biliary tract carcinoma: current status and emerging strategies. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(11):338-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Goeppert B, Frauenschuh L, Zucknick M, et al. Prognostic impact of tumour-infiltrating immune cells on biliary tract cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(10):2665-2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Asahi Y, Hatanaka KC, Hatanaka Y, et al. Prognostic impact of CD8+ T cell distribution and its association with the HLA class I expression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2020;50(8):931-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jiang P, Gu S, Pan D, et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat Med. 2018;24(10):1550-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Litchfield K, Reading JL, Puttick C, et al. Meta-analysis of tumor- and T cell-intrinsic mechanisms of sensitization to checkpoint inhibition. Cell. 2021;184(3):596-614.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ott PA, Bang Y-J, Piha-Paul SA, Bennouna J, Soria J-C, Mehnert JM, et al. T-cell–inflamed gene-expression profile, programmed death ligand 1 expression, and tumor mutational burden predict efficacy in patients treated with pembrolizumab across 20 cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4):318-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.