This case-control study characterizes the self-awareness of poor olfaction in women, including its prevalence, associated factors, reporting reliability, validity against an objective test, and factors associated with validity.

Key Points

Question

What factors may be associated with the self-awareness of poor olfaction in middle-aged and older adults?

Findings

In this case-control study of middle-aged and older women, there was a low sensitivity (22.6%) in reporting poor olfaction, which was particularly true for non-Hispanic Black women vs non-Hispanic White women (12.4% vs 24.4%) despite the prevalence of their objectively tested poor olfaction being twice as common (24.5% vs 12.5%). Furthermore, age, education, underweight, fair or poor health, Parkinson disease, and seasonal allergy may also be associated with the accuracy of self-reported poor olfaction.

Meaning

These study findings suggest that self-awareness and reporting accuracy of poor olfaction in middle-aged and older women are low, particularly in non-Hispanic Black women.

Abstract

Importance

Poor olfaction is common in older adults and signifies multiple adverse health outcomes, but it often goes unrecognized.

Objective

To characterize the self-awareness of poor olfaction in women, including its prevalence, associated factors, reporting reliability, validity against an objective test, and factors associated with validity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

These cross-sectional survey data and a case-control subsample were taken from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Sister Study. Of 41 118 participants (aged 41-85 years) who reported olfaction in 2014 through 2016, 3406 (aged 50-79 years) reported olfaction again in 2018 through 2019 and completed the 12-item Brief Smell Identification Test, version A, including 2353 women who self-reported poor olfaction in 2014 through 2016 and 1053 women who reported normal olfaction. Data analyses were performed between May 28, 2021, and December 23, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Self-reported (yes/no) and objectively tested poor olfaction defined as a Brief Smell Identification Test score of 9 or lower. Multivariable logistic regressions were used to assess factors that might be associated with the prevalence and reporting accuracy of self-reported olfaction. In subsample analyses, the sampling strategy was accounted for to extrapolate data to eligible cohort samples.

Results

Of the 41 118 women (mean [SD] age, 64.3 [8.7] years) included in the analysis, 3322 (8.1%) self-reported poor olfaction. Higher prevalence was associated with older age, not being married, current smoking status, frequent coffee drinking, overweight or obesity, less than optimal health, Parkinson disease, cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety, and seasonal allergy, whereas a lower prevalence was associated with non-Hispanic Black race and physical activity. In the subsample analyses, olfaction status reported 3 years apart showed a modest agreement (κ, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.51-0.61). The prevalence of objectively tested poor olfaction was 13.3% (95% CI, 11.5%-15.0%), and in contrast with self-reports, it was twice as high in non-Hispanic Black women as in non-Hispanic White women (24.5% vs 12.5%). Compared with objective tests, self-reports showed a low sensitivity (22.6%; 95% CI, 19.6%-25.6%), especially in non-Hispanic Black women (12.4%; 95% CI, 7.0%-17.8%). The specificity was uniformly high (>90%). Among participants who reported poor olfaction, higher odds of true vs false positives were associated with age older than 60 years (60-64 years old, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.51-1.87; 65-69 years old, 2.26; 95% CI, 2.03-2.51; 70-74 years old, 3.34; 95% CI, 3.00-3.73; ≥75 years old, 5.17; 95% CI, 4.43-6.03), non-Hispanic Black race (2.00; 95% CI, 1.70-2.36), no college education (1.34; 95% CI, 1.22-1.48), underweight (1.40; 95% CI, 1.04-1.88), fair or poor health (1.37; 95% CI, 1.22-1.54), and Parkinson disease (7.60; 95% CI, 5.60-10.32). Among those with objectively tested poor olfaction, lower odds of true positives vs false negatives were associated with Black race (0.46; 95% CI, 0.25-0.86).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this case-control study, the self-awareness and reporting accuracy of poor olfaction in middle-aged and older women were low, particularly in non-Hispanic Black women. Given its potential health implications, awareness of this common sensory deficit should be raised.

Introduction

The sense of smell in humans decreases with age, and poor olfaction affects about 15% to 25% of older adults.1,2 Poor olfaction adversely affects essential human functions such as detecting environmental hazards,3 diet and nutrition,4 emotional and physical well-being,5,6 and quality of life.7 Importantly, poor olfaction predicts higher mortality among older adults8,9,10,11 and is an important prodromal symptom of dementia and Parkinson disease (PD).11

Unlike vision or hearing impairments, poor olfaction often goes unrecognized. Most studies to date have shown that fewer than a third of those with poor olfaction know they have it.1,2 Nonetheless, in the general population, self-recognition is often how symptoms are first identified and may capture information such as perceived changes over time that is difficult to capture with a single objective test.12,13,14,15 We hereby examined the prevalence of both self-reported and objectively tested poor olfaction in a large population of women. We identified factors that were associated with self-reported poor olfaction and studied reporting reliability, validity against an objective test, and factors that may be associated with the reporting validity.

Methods

Study Population

The Sister Study is a nationwide cohort established by investigators from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to investigate environmental and genetic risk factors for breast cancer and other chronic diseases.16 The original study population includes 45 068 participants of the third comprehensive follow-up of the Sister Study in 2014 through 2016. In 2018 through 2019, we further selected a subsample of Sister Study participants to specifically investigate risk factors and potential health consequences of poor olfaction. The eligibility criteria of this olfaction substudy included (1) a valid answer to the self-reported olfaction status at the third follow-up of the Sister Study in 2014 through 2016, and (2) presumed alive and aged 50 to 79 years as of January 1, 2018. Of the 36 492 women eligible, we invited all participants who reported poor olfaction (n = 2820) at the third follow-up and 1200 randomly selected participants with normal self-reports to complete the self-administered Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT), version A, distributed by mail. Data were collected between March 2018 and February 2019 with B-SIT booklets returned by 2353 (83.4%) self-reported cases and 1053 (87.8%) self-reported controls. Details of the study population and the olfaction substudy data collection are presented in eFigure 1 in the Supplement. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Michigan State University, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Defense. Participants provided consent through completing and returning the study materials.

Self-reported Olfaction

At the third follow-up survey of the Sister Study in 2014 through 2016, we asked participants “Do you suffer from a decrease in or loss of your sense of smell?” and for those who answered “yes” we further asked, “How old were you the first time you noticed this problem?” and “Are there any reasons (such as head injury) that explain the decrease in your sense of smell?” In the olfaction substudy in 2018 through 2019, we repeated the questions about poor olfaction and age it was first noticed.

Objective Olfaction Testing

The objective olfaction testing was conducted only among participants of the olfaction substudy in 2018 through 2019, using the B-SIT. This test is a validated shorter version of the 40-item University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test and has been widely used in clinical and epidemiological studies.17,18,19,20 The B-SIT was designed to be self-administered, either by mail or in person.21 The test is a small booklet that contains 12 commonly experienced odorants (eg, soap, smoke, lemon),22 1 embedded on a page. Participants are instructed to scratch and smell each of these odorants, 1 at a time, and to identify the correct odorant from 4 possible answers in a forced multiple-choice format.21 This odor identification test is scored as number correct, with a higher score indicating a better sense of smell.22 Considering the sex and age of the study participants, we used a cutoff score of 9 or lower for poor olfaction.

Covariates Assessed at the Third Follow-up Survey

The covariates were mainly from the third comprehensive follow-up survey, including demographics (ie, age, race and ethnicity [non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other, including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and all those of Hispanic ethnicity regardless of race], education level [below college vs some college or higher], and marital status [married or living as married vs not married]); lifestyle choices (ie, smoking [never, past, and current], alcohol drinking [never, past, and current], coffee consumption [cups/wk], physical activities [min/wk], and body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared [<18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25-29.9, and ≥30]); self-reported health status; self-reported PD diagnosis; cognitive impairment (AD-8 score >3); depression (2-item Patient Health Questionnaire score ≥3 or current use of antidepressants); anxiety (2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale ≥3); and seasonal allergy/hay fever.

Relevant Medical History Assessed at the Olfaction Substudy

In the olfaction substudy in 2018 through 2019, we further asked about health conditions that may affect olfaction, including nasal polyps, chronic rhinosinusitis, recurrent acute rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis/seasonal allergy/hay fever, cold or flu longer than 1 month, ear infection, persistent dry mouth, treatment for head and neck cancer, chemotherapy for cancer, head injury with loss of consciousness, broken nose, trauma to head or face, and surgery on nose or brain. Furthermore, we asked about history of chronic conditions that may affect the sense of smell, including PD, Alzheimer disease or dementia, mild cognitive impairment, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, depression, anxiety, any other neurologic diseases, any other psychiatric diseases, and chronic kidney disease.

Statistical Analysis

We first calculated the prevalence of self-reported poor olfaction among eligible participants in the Sister Study who answered the sense of smell question at the third follow-up survey. We analyzed lifestyle and health factors in relation to self-reported poor olfaction using logistic regression models and reported odds ratios and 95% CIs, adjusting for age, race, education, and marital status when appropriate. Subsequent analyses were based on participants who also participated in the olfaction substudy. We first examined the agreement between self-reported poor olfaction in the substudy with that of the third follow-up using κ statistics, with the understanding that the second assessment was on average a mean (SD) of 3.0 (0.5) years after the first. We also examined medical conditions collected at the substudy in relation to the prevalence of self-reported poor olfaction, using multivariable logistic regression models.

We considered the B-SIT as the objective measure of olfaction. We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of self-reports at both third follow-up and substudy, using B-SIT as the gold standard. Finally, we identified potential predictors for the accuracy of self-reported sense of smell status. In this analysis, we focused on identifying factors that may influence the reporting accuracy when someone reported poor olfaction (ie, true positive vs false positive) and when B-SIT tested poor sense of smell (ie, true positive vs false negative). Accordingly, we reported odds ratios and 95% CIs calculated using logistic regression (eg, the odds ratio for true vs false positive among those who reported a poor sense of smell).

In the descriptive analyses, we presented mean (SD) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Because we know the exact sampling frame from which the substudy samples were drawn, in all analyses using substudy data, we accounted for sampling strategy and used weights in the analysis to extrapolate estimates back to all sampling-eligible participants (n = 36 492). All statistical analyses were conducted from Sister Study data release 8.2 using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), with 2-sided α = .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

At the third follow-up, of the 41 118 participants, 3322 (8.1%) reported a poor sense of smell. The prevalence increased with age (5.6% for <60 years old, 8.0% for 60-64 years old, 8.5% for 65-69 years old, 9.8% for 70-74 years old, and 11.7% for ≥75 years old) and was higher in White women (8.3%) than in Black women (6.1%) or women of other races (7.1%). A total of 3129 (94.2%) women further recalled the age when they first noticed this symptom (111 [3.6%] <20 years old, 286 [9.1%] 20-39 years old, 388 [12.4%] 40-49 years old, 902 [28.8%] 50-59 years old, 907 [29.0%] 60-69 years old, and 535 [17.1%] ≥70 years old). In contrast, only 986 (29.7%) women were able to give a reason that might have caused their poor sense of smell. Of these, inflammatory sinonasal diseases were most reported (392 [40.0%]), followed by traumatic head injury (100 [10.1%]), sinonasal surgery (76 [7.7%]), postviral smell loss (64 [6.5%]), neurologic disease (61 [6.2%]), and smoking (55 [5.6%]).

As expected, the odds of reporting poor olfaction increased with age (Table 1). It was also positively associated with not being married, current smoking status, drinking more than 14 cups of coffee per week, overweight or obesity, less than optimal health, history of PD, cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety, and seasonal allergy. In contrast, Black race and physical activities were associated with lower odds of reporting a poor sense of smell.

Table 1. Population Characteristics by Self-reported Olfaction at the Third Follow-up of the Sister Study.

| Characteristic | Self-reported poor olfaction, No.a | Prevalence, % | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crudeb | Adjustedc | ||||

| Yes (n = 3322) | No (n = 37 796) | ||||

| Age, y | |||||

| <60 | 743 | 12 431 | 5.6 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 60-64 | 684 | 7829 | 8.0 | 1.46 (1.31-1.63) | 1.45 (1.30-1.62) |

| 65-69 | 686 | 7423 | 8.5 | 1.55 (1.39-1.72) | 1.53 (1.38-1.71) |

| 70-74 | 604 | 5541 | 9.8 | 1.82 (1.63-2.04) | 1.79 (1.60-2.00) |

| ≥75 | 605 | 4572 | 11.7 | 2.21 (1.98-2.48) | 2.14 (1.91-2.40) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 159 | 2429 | 6.1 | 0.72 (0.61-0.85) | 0.75 (0.64-0.89) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2981 | 32 989 | 8.3 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherd | 181 | 2371 | 7.1 | 0.84 (0.72-0.99) | 0.90 (0.77-1.05) |

| Education | |||||

| Some college or higher | 2836 | 32 362 | 8.1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| No college | 485 | 5427 | 8.2 | 1.02 (0.92-1.13) | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married or living as married | 2138 | 25 690 | 7.7 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Not married | 1076 | 10 978 | 8.9 | 1.18 (1.09-1.27) | 1.10 (1.02-1.19) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 1822 | 21 642 | 7.8 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past | 1345 | 14 705 | 8.4 | 1.09 (1.01-1.17) | 1.02 (0.95-1.10) |

| Current | 154 | 1442 | 9.6 | 1.27 (1.07-1.51) | 1.37 (1.15-1.63) |

| Alcohol drinking | |||||

| Never | 102 | 1129 | 8.3 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past | 814 | 7694 | 9.6 | 1.17 (0.94-1.44) | 1.21 (0.97-1.50) |

| Current | 2405 | 28 967 | 7.7 | 0.91 (0.74-1.12) | 0.99 (0.80-1.22) |

| Regular coffee drinking, cups/wk | |||||

| 0 | 887 | 10 228 | 8.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-6 | 903 | 10 436 | 8.0 | 1.00 (0.91-1.10) | 1.00 (0.91-1.10) |

| 7-14 | 800 | 9436 | 7.8 | 0.98 (0.88-1.08) | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) |

| >14 | 564 | 5812 | 8.8 | 1.12 (1.00-1.25) | 1.12 (1.00-1.25) |

| Vigorous activity, min/wk | |||||

| 0 | 1887 | 19 508 | 8.8 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-120 | 543 | 6351 | 7.9 | 0.88 (0.80-0.98) | 0.95 (0.86-1.06) |

| >120 | 674 | 9496 | 6.6 | 0.73 (0.67-0.80) | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) |

| Moderate activity, min/wk | |||||

| 0 | 1063 | 11 021 | 8.8 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-120 | 711 | 8429 | 7.8 | 0.87 (0.79-0.97) | 0.92 (0.84-1.02) |

| 121-240 | 582 | 6812 | 7.9 | 0.89 (0.80-0.98) | 0.89 (0.80-0.99) |

| >240 | 719 | 8696 | 7.6 | 0.86 (0.78-0.95) | 0.84 (0.76-0.92) |

| Walking, min/wk | |||||

| 1-80 | 977 | 9600 | 9.2 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 81-210 | 858 | 9845 | 8.0 | 0.86 (0.78-0.94) | 0.86 (0.78-0.95) |

| 211-420 | 593 | 7452 | 7.4 | 0.78 (0.70-0.87) | 0.78 (0.70-0.87) |

| >420 | 692 | 8565 | 7.5 | 0.79 (0.72-0.88) | 0.78 (0.71-0.87) |

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 62 | 588 | 9.5 | 1.31 (1.00-1.71) | 1.23 (0.94-1.61) |

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 1189 | 14 783 | 7.4 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 1094 | 12 165 | 8.3 | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) |

| Obese (≥30) | 976 | 10 259 | 8.7 | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) | 1.25 (1.14-1.36) |

| Overall health status | |||||

| Excellent or very good | 1851 | 25 564 | 6.8 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Good | 1013 | 9130 | 10.0 | 1.53 (1.41-1.66) | 1.51 (1.39-1.63) |

| Fair or poor | 425 | 2832 | 13.0 | 2.07 (1.85-2.32) | 2.00 (1.78-2.24) |

| Parkinson disease | |||||

| No | 3209 | 37 618 | 7.9 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 113 | 178 | 38.8 | 7.44 (5.86-9.45) | 6.52 (5.13-8.30) |

| Cognitive impairment | |||||

| Normal | 2320 | 31 170 | 6.9 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Likely to be present | 721 | 4103 | 14.9 | 2.36 (2.16-2.58) | 2.26 (2.07-2.48) |

| Depression | |||||

| No | 2743 | 33 219 | 7.6 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 562 | 4430 | 11.3 | 1.54 (1.40-1.69) | 1.56 (1.42-1.72) |

| Anxiety | |||||

| No | 2684 | 32 330 | 7.7 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 623 | 5313 | 10.5 | 1.41 (1.29-1.55) | 1.46 (1.33-1.60) |

| Seasonal allergy | |||||

| No | 1493 | 21 361 | 6.5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1811 | 16 267 | 10.0 | 1.59 (1.48-1.71) | 1.64 (1.53-1.76) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

If the number of missing values was greater than or equal to 100, missing values were coded as a separate category. If the number of missing values was less than 100, missing values were coded as the least exposed category.

Unadjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated for each individual exposure of interest.

Multivariable odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated for each individual exposure of interest one at a time, adjusting for age, race, education, and marital status when applicable.

The Other category includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and all those of Hispanic ethnicity regardless of race.

Self-reported olfaction status in the substudy showed a moderate agreement with that from the third follow-up (κ = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.51-0.61). The weighted prevalence of self-reported poor olfaction was 11.1% (95% CI, 9.8%-12.4%). Again, the prevalence increased with age (from 8.6% for ages 50-59 years to 18.4% for ages ≥75 years) and was higher in White women (11.7%) than in Black women (5.2%) or women of other races and ethnicities (10.0%).

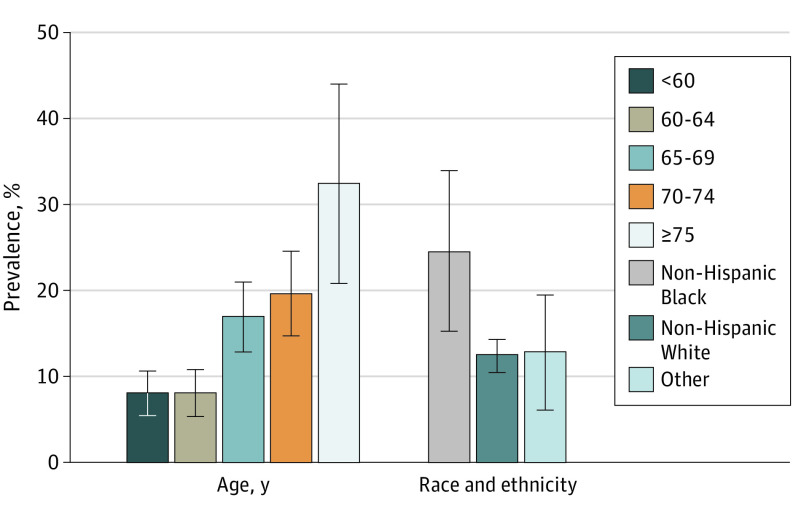

Self-reported poor olfaction was associated with a history of nasal polyps, chronic or acute recurrent rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, cold or flu lasting for longer than a month, persistent dry mouth, broken nose, head trauma, surgery on nose or brain, a history of PD, depression, anxiety, other neurologic diseases, and other psychiatric diseases (eTable in the Supplement). eFigure 2 in the Supplement shows the distribution of B-SIT testing scores by self-reported olfaction at the third follow-up. Participants who reported poor olfaction performed worse on the test than those who reported normal olfaction. The estimated prevalence of B-SIT–tested poor olfaction was 13.3% (95% CI, 11.5%-15.0%). Compared with participants younger than 65 years, the prevalence of poor olfaction was doubled for those aged 65 to 74 years and quadrupled for those older than 75 years (Figure). In contrast with self-reports, objectively tested poor olfaction was about twice as common in non-Hispanic Black women (24.5%) than in non-Hispanic White women (12.5%) or women of other race and ethnicity groups (12.8%).

Figure. Prevalence of Objectively Tested Poor Olfaction by Age and Race and Ethnicity.

Estimates were extrapolated to all eligible study participants from the third follow-up survey of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Sister Study, accounting for study design. Poor olfaction was defined as a score of 9 or lower on the Brief Smell Identification Test, version A. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. The Other race and ethnicity category includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and all those of Hispanic ethnicity regardless of race.

Self-reported poor olfaction at the third follow-up had a low sensitivity (22.6%; 95% CI, 19.6%-25.6%), especially among Black women (12.4%; 95% CI, 7.0%-17.8%) (Table 2). The specificity was uniformly high (≥94.0%) across age and race and ethnicity groups. Consistent with low sensitivity, the PPV was also relatively low (38.9%). The PPV, however, increased steadily with age, rising from 23.8% for those younger than 60 years to 61.7% for those 75 years and older, reflecting higher prevalence among older individuals. The NPV was high (83.8%-94.3%) except for in those older than 75 years (70.9%). Compared with White women and women of other races, Black women had a higher PPV and a lower NPV, likely owing to their higher prevalence of poor olfaction (Table 2). In comparison, self-report at the substudy showed higher sensitivity in White women (35.5%), but the sensitivity in Black women remained low (10.6%).

Table 2. Validity of Self-reported vs Objectively Tested Poor Olfaction by Age and Race and Ethnicitya.

| Characteristic | % (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-report at the third follow-up | Self-report at the substudy | |||||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

| Overall | 22.6 (19.6-25.6) | 94.6 (94.4-94.7) | 38.9 (38.0-39.7) | 88.9 (87.0-90.8) | 31.9 (26.3-37.5) | 92.2 (90.9-93.4) | 38.0 (32.3-43.6) | 90.0 (88.2-91.8) |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| <60 | 16.7 (11.3-22.1) | 95.3 (94.9-95.7) | 23.8 (22.4-25.3) | 92.9 (90.2-95.6) | 18.2 (10.5-25.8) | 92.4 (90.2-94.6) | 17.3 (10.9-23.7) | 92.8 (90.1-95.5) |

| 60-64 | 34.3 (22.1-46.4) | 94.3 (93.6-94.9) | 34.4 (32.8-36.0) | 94.3 (91.2-97.3) | 50.4 (32.3-68.4) | 94.2 (92.4-96.0) | 42.3 (30.1-54.6) | 95.8 (93.3-98.3) |

| 65-69 | 20.1 (14.9-25.4) | 94.1 (93.4-94.8) | 41.0 (39.4-42.7) | 85.2 (80.8-89.7) | 34.2 (23.0-45.4) | 90.4 (87.3-93.5) | 41.3 (29.8-52.7) | 87.5 (83.2-91.7) |

| 70-74 | 25.4 (18.5-32.3) | 94.0 (93.1-94.9) | 50.7 (48.9-52.5) | 83.8 (78.3-89.2) | 29.3 (19.6-39.0) | 91.2 (87.7-94.6) | 45.0 (32.7-57.3) | 83.9 (78.5-89.3) |

| ≥75 | 19.3 (11.2-27.4) | 94.3 (92.3-96.2) | 61.7 (58.6-64.8) | 70.9 (58.1-83.8) | 34.0 (15.5-52.5) | 90.5 (82.2-98.8) | 62.5 (37.2-87.7) | 74.7 (61.9-87.6) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.4 (7.0-17.8) | 96.0 (94.9-97.2) | 50.3 (46.5-54.0) | 77.1 (67.2-87.1) | 10.6 (5.9-15.4) | 96.5 (94.5-98.4) | 48.0 (35.3-60.8) | 77.8 (68.1-87.6) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 24.4 (20.8-28.0) | 94.5 (94.3-94.6) | 38.5 (37.6-39.3) | 89.8 (87.8-91.7) | 35.5 (29.0-42.1) | 91. 9 (90.5-93.3) | 38.1 (32.1-44.2) | 91.0 (89.1-92.9) |

| Otherb | 19.0 (8.3-29.7) | 94.8 (93.5-96.0) | 34.7 (31.1-38.3) | 88.9 (81.7-96.1) | 23.9 (5.5-42.2) | 91.9 (86.7-97.1) | 30.0 (9.3-50.7) | 89.2 (82.1-96.3) |

Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Objectively tested poor olfaction was defined as a score of 9 or lower on the Brief Smell Identification Test, version A.

The Other category includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and all those of Hispanic ethnicity regardless of race.

Factors associated with the validity of self-reports from both the third follow-up and the substudy were also analyzed. For self-reports at the third follow-up, among those who reported poor olfaction, the odds of true vs false positives were associated with older age, Black race, no college education, current smoking, current and/or past alcohol drinking, being underweight, self-reported fair or poor health, and PD (Table 3). In contrast, a history of allergy or depression was associated with false positives. Among those who tested poorly on the B-SIT, only an age of 60 to 64 years (vs <60 years) was associated with higher odds of correctly reporting a poor sense of smell. In contrast, Black race and vigorous physical activity were associated with the odds of false negatives. Because all patients with PD and poor olfaction correctly reported their sense of smell, this specific analysis for PD was not conducted.

Table 3. Factors Associated With the Accuracy of Self-reported vs Objectively Tested Poor Olfaction.

| Characteristics | Odds ratio (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-report at the third follow-up | Self-report at the substudy | |||

| True vs false positivesb | True positives vs false negativesc | True vs false positivesb | True positives vs false negativesc | |

| Age, y | ||||

| <60 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 60-64 | 1.68 (1.51-1.87) | 2.49 (1.22-5.07) | 3.68 (1.84-7.34) | 4.84 (1.88-12.44) |

| 65-69 | 2.26 (2.03-2.51) | 1.25 (0.71-2.19) | 3.65 (1.87-7.13) | 2.54 (1.16-5.55) |

| 70-74 | 3.34 (3.00-3.73) | 1.61 (0.89-2.92) | 4.08 (2.01-8.28) | 1.89 (0.88-4.05) |

| ≥75 | 5.17 (4.43-6.03) | 1.07 (0.51-2.21) | 8.60 (2.65-27.89) | 2.43 (0.88-6.69) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.00 (1.70-2.36) | 0.46 (0.25-0.86) | 2.01 (0.99-4.10) | 0.27 (0.13-0.54) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Otherd | 0.96 (0.82-1.12) | 0.72 (0.31-1.65) | 1.09 (0.47-2.51) | 0.51 (0.16-1.65) |

| Education | ||||

| Some college or higher | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| No college | 1.34 (1.22-1.48) | 0.95 (0.55-1.63) | 1.29 (0.64-2.61) | 0.53 (0.26-1.06) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or living as married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Not married | 1.03 (0.95-1.12) | 0.93 (0.59-1.46) | 0.64 (0.37-1.12) | 0.51 (0.28-0.91) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Former | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) | 0.94 (0.61-1.43) | 0.62 (0.38-1.00) | 0.42 (0.24-0.71) |

| Current | 1.49 (1.24-1.79) | 1.97 (0.62-6.27) | 1.10 (0.28-4.39) | 2.18 (0.46-10.30) |

| Alcohol drinking | ||||

| Never | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Past | 1.55 (1.21-1.98) | 1.13 (0.39-3.27) | 0.43 (0.11-1.63) | 0.77 (0.18-3.30) |

| Current | 1.44 (1.14-1.83) | 1.40 (0.51-3.85) | 0.51 (0.14-1.81) | 0.99 (0.25-3.99) |

| Coffee drinking, cups/wk | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-6 | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 1.75 (0.96-3.20) | 1.08 (0.59-1.97) | 0.96 (0.44-2.09) |

| 7-14 | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | 1.42 (0.80-2.52) | 1.14 (0.56-2.32) | 1.42 (0.63-3.18) |

| >14 | 1.00 (0.90-1.12) | 1.14 (0.63-2.08) | 0.64 (0.30-1.36) | 0.56 (0.26-1.22) |

| Vigorous activity, min/wk | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-120 | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) | 0.64 (0.35-1.16) | 0.96 (0.50-1.85) | 0.90 (0.40-2.00) |

| >120 | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) | 0.58 (0.35-0.96) | 1.21 (0.64-2.29) | 0.97 (0.49-1.94) |

| Moderate activity, min/wk | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-120 | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | 0.88 (0.48-1.63) | 0.92 (0.44-1.93) | 0.98 (0.42-2.28) |

| 121-240 | 1.06 (0.96-1.18) | 1.04 (0.55-1.94) | 1.18 (0.57-2.41) | 1.17 (0.52-2.63) |

| >240 | 0.92 (0.84-1.02) | 0.65 (0.38-1.14) | 0.95 (0.48-1.89) | 0.54 (0.26-1.11) |

| Walking, min/wk | ||||

| 0-80 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 81-210 | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) | 1.27 (0.71-2.29) | 0.59 (0.31-1.13) | 0.79 (0.37-1.72) |

| 211-420 | 1.07 (0.97-1.19) | 1.24 (0.65-2.36) | 0.66 (0.32-1.38) | 1.07 (0.45-2.55) |

| >420 | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | 1.02 (0.58-1.77) | 0.88 (0.48-1.64) | 0.93 (0.44-1.96) |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1.40 (1.04-1.88) | 1.31 (0.14-12.13) | 2.35 (1.10-5.02) | 7.78 (2.14-28.26) |

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) | 1.20 (0.73-1.97) | 1.09 (0.59-2.03) | 0.86 (0.44-1.69) |

| Obese (≥30) | 1.07 (0.98-1.17) | 1.40 (0.82-2.40) | 0.79 (0.43-1.46) | 1.05 (0.52-2.10) |

| Overall health status | ||||

| Excellent or very good | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Good | 1.03 (0.95-1.11) | 1.12 (0.71-1.77) | 1.56 (0.91-2.69) | 1.35 (0.71-2.56) |

| Fair or poor | 1.37 (1.22-1.54) | 1.10 (0.56-2.18) | 1.43 (0.81-2.52) | 0.76 (0.35-1.67) |

| Parkinson disease | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 7.60 (5.60-10.32) | NA | 7.97 (4.46-14.26) | 40.54 (10.37-158.46) |

| Seasonal allergy | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.75 (0.70-0.81) | 1.35 (0.90-2.04) | 0.69 (0.42-1.13) | 1.15 (0.66-1.99) |

| Cognitive impairment | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.95 (0.87-1.03) | 1.83 (0.95-3.53) | 1.60 (0.92-2.77) | 2.09 (0.81-5.36) |

| Depression | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.90 (0.82-0.99) | 1.25 (0.68-2.29) | 1.01 (0.56-1.83) | 1.39 (0.62-3.11) |

| Anxiety | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.95 (0.86-1.04) | 1.53 (0.85-2.76) | 0.91 (0.51-1.61) | 1.04 (0.49-2.17) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; NA, not applicable.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated for each individual exposure of interest one at a time, adjusting for age, race, education, and marital status when applicable.

Among participants who reported poor olfaction.

Among participants with objectively tested poor olfaction, defined as a score of 9 or lower on the Brief Smell Identification Test, version A.

The Other category includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and all those of Hispanic ethnicity regardless of race.

The analysis of self-reports from the substudy showed similar results overall, but there are some differences. Among women with self-reported poor olfaction, older age, being underweight, and PD were associated with true positives. Among women with objectively tested poor olfaction, certain age groups (60-64 and 65-69 years old), being underweight, and PD were associated with the odds of true positives, while Black race, not being married, and being a former smoker were associated with the odds of false negatives (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to characterize the self-awareness of poor olfaction in a general population. In this well-educated female population, the prevalence of self-reported poor olfaction was lower than that based on an objective test. Self-report had moderate reliability when reassessed 3 years later. Multiple demographic (eg, race and marital status), lifestyle (eg, smoking status and coffee drinking), and health conditions (eg, general health status and PD) were associated with self-reporting poor olfaction. Compared with the objectively tested olfaction, self-report had low sensitivity but high specificity, consistent with previous reports suggesting that the majority of those with poor olfaction do not realize it.1,12,23 This appears to be particularly true for Black women. We also identified a few factors that may alter the reporting accuracy when compared with the objective tests, such as age and having PD.

Poor olfaction is common in older adults and is age dependent. The present data using the B-SIT are consistent with the literature that poor olfaction affects about 15% to 25% of older adults,1,2 considering this study population was female, predominantly White, and relatively young. This sensory deficit has been studied as a prodromal symptom of PD and dementia, and as a predictor of total mortality.8,9,10,11 Recent studies further suggest that poor olfaction may have profound health implications beyond neurodegenerative diseases, supported by preliminary evidence for links to diabetes, depression, functional declines, frailty, loss of lean mass, and pneumonia in older adults.24,25,26,27,28,29 Thus, early awareness of this common sensory deficit may help identify impending health issues and conduct interventional research to prevent them.

Despite the potential profound health implications of poor olfaction in older adults, the awareness of this sensory deficit by the general public is low. Even in this population of health-conscious women, only 20% to 30% of those with an objectively tested poor smell identification recognized this deficit. This is consistent with the literature that shows a low sensitivity of self-reported poor olfaction in older adults when compared with an objective test.1,12,13,30 Given its potential health implications, there is a great need to raise the awareness in older adults of olfactory deficit.

Several population-based studies in the United States, Sweden, and Korea have reported factors associated with self-reported poor olfaction in adults.31,32,33,34,35,36 They have found that poor olfaction was more likely to be reported by individuals with older age,33,34,36 non-Hispanic White race (vs non-Hispanic Black or Asian race),33 smoking,32 heavy alcohol drinking,31 low income or income-to-poverty ratio,31,34 exposure to air pollutants,34 presence of sinonasal symptoms,31,34 persistent dry mouth,31 tinnitus,35 and head injury with loss of consciousness.31 Most of these observations were confirmed in the current female-only study population. Furthermore, we found a statistically significant association of self-reported poor olfaction with unmarried status, self-rated fair to poor health status, low physical activity, overweight or obesity, and a history of certain medical conditions (eg, PD, cognitive impairment, depression, broken nose). Some observations on factors associated with self-reported poor olfaction (eg, PD and self-rated health) are consistent with findings based on objectively tested olfaction.2,37 But the finding on race contrasts with that from studies using objective tests where Black individuals are more likely to have poor olfaction than White individuals.2,38

To our knowledge, only 1 study investigated factors that may influence the accuracy of self-reported poor olfaction in the general population.23 In the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (n = 1468; ages 57-85 years), of those who reported poor olfaction, only older age was associated with a higher likelihood of true vs false positives. In contrast, among participants with objectively tested poor olfaction, younger age, White race, being married, and higher cognitive score were associated with a higher likelihood of true positives.

Compared with the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, the present study participants are women only, predominantly White, and younger. We confirmed their findings on age among participants who self-reported poor olfaction and additionally identified several other factors that are associated with true positives (eg, Black race and PD), likely owing to the higher prevalence of olfaction impairment in these groups.1,2 We also confirmed their findings among those who had an objectively tested poor olfaction that Black individuals, former smokers, and unmarried people had higher odds of false negatives, indicating lower awareness.23 This finding on race is particularly interesting. Multiple studies2,38 found that Black individuals are about twice as likely to have poor olfaction, yet they were less likely to report it, as shown in this and a previous study.23 Therefore, raising the awareness of this sensory deficit in older Black adults is particularly needed.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has notable strengths, such as a large sample size and 2 time points for assessments of self-reported olfaction. To our knowledge, some of the data are among the first in the field, for example, to report reliability over time in the general population. However, the study also has multiple limitations. First, the study population is women only, and findings may not be readily generalizable to men. Second, considering the study population’s relatively young age and female sex, we used an arbitrary cutoff of a B-SIT score of 9 or lower to define poor olfaction. While this cutoff has been used in previous studies,39,40 other cutoffs have also been used.2,41 A different cutoff choice will influence the evaluations of validity measures of self-reported olfaction. Furthermore, the low sensitivity of self-reported poor olfaction may also be partly owing to the possibility that mild olfactory loss may have a limited influence on the quality of life of older adults. Third, owing to the limited literature on factors that may affect the awareness of poor olfaction in older adults,23 these study findings should be considered preliminary. Fourth, the 2 self-reports were about 3 years apart, and the B-SIT was only conducted in a substudy sample. Therefore, the reliability and validity findings of self-reports must be interpreted with the caveat that they were 3 years apart, during which the sense of smell might have changed. Furthermore, the self-reported causes of poor olfaction might be subject to recall errors and potential biases. Fifth, both self-reports and the olfactory testing in the current study focused on smell identification, as did in nearly all large epidemiological studies in older adults.1,2 A few studies (eg, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) also tried to ask for other olfactory distortions such as parosmia or phantosmia.31 Potential roles of such olfaction deficits in health are yet to be investigated. Lastly, all data collection was completed before the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, all assessments and analyses regarding self-awareness of olfactory impairment did not take the effect of the pandemic into consideration.

Conclusions

In this case-control study, we confirmed that poor sense of smell is common in middle-aged older women and that the prevalence is age dependent. However, the self-awareness of this sensory deficit is very low even in this well-educated and health-conscious female population. Given the increasingly recognized profound adverse health implications of poor olfaction in older adults,10,11,37,42 there is a need to increase the awareness of this common sensory deficit by the general public.

eTable. Medical Conditions and Self-reported Olfaction at the Olfaction Sub-Study

eFigure 1. Sample Selection and Participation of the Olfactory Sub-Study

eFigure 2. B-SIT Score Distribution in the Olfaction Sub-Study (2018-2019), by Self-Reported Olfaction at the Third Follow-Up of the Sister Study (2014-2016)

References

- 1.Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BEK, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 2002;288(18):2307-2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong J, Pinto JM, Guo X, et al. The prevalence of anosmia and associated factors among U.S. black and white older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(8):1080-1086. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pence TS, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, Costanzo RM. Risk factors for hazardous events in olfactory-impaired patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(10):951-955. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aschenbrenner K, Hummel C, Teszmer K, et al. The influence of olfactory loss on dietary behaviors. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):135-144. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318155a4b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuland C, Bitter T, Marschner H, Gudziol H, Guntinas-Lichius O. Health-related and specific olfaction-related quality of life in patients with chronic functional anosmia or severe hyposmia. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(4):867-872. doi: 10.1002/lary.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smeets MAM, Veldhuizen MG, Galle S, et al. Sense of smell disorder and health-related quality of life. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54(4):404-412. doi: 10.1037/a0017502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T. Olfactory disorders and quality of life—an updated review. Chem Senses. 2014;39(3):185-194. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devanand DP, Lee S, Manly J, et al. Olfactory identification deficits and increased mortality in the community. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):401-411. doi: 10.1002/ana.24447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, Schumm LP, McClintock MK. Olfactory dysfunction predicts 5-year mortality in older adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e107541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert CR, Fischer ME, Pinto AA, et al. Sensory impairments and risk of mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(5):710-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Luo Z, Pinto JM, et al. Relationship between poor olfaction and mortality among community-dwelling older adults: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(10):673-681. doi: 10.7326/M18-0775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehling E, Lundervold AJ, Nordin S. Does it matter how we pose the question “how is your sense of smell?”. Chemosens Percept. 2014;7(3-4):103-107. doi: 10.1007/s12078-014-9171-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman HJ, Rawal S, Li CM, Duffy VB. New chemosensory component in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): first-year results for measured olfactory dysfunction. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17(2):221-240. doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9364-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonhardt B, Tahmasebi R, Jagsch R, Pirker W, Lehrner J. Awareness of olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2019;33(5):633-641. doi: 10.1037/neu0000544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis BN, Hummel T, Hugentobler M, Giger R, Lacroix JS. Ratings of overall olfactory function. Chem Senses. 2003;28(8):691-694. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjg061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandler DP, Hodgson ME, Deming-Halverson SL, et al. ; Sister Study Research Team . The Sister Study cohort: baseline methods and participant characteristics. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(12):127003. doi: 10.1289/EHP1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, et al. Association of olfactory dysfunction with risk for future Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(2):167-173. doi: 10.1002/ana.21291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Double KL, Rowe DB, Hayes M, et al. Identifying the pattern of olfactory deficits in Parkinson disease using the brief smell identification test. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(4):545-549. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.4.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kjelvik G, Sando SB, Aasly J, Engedal KA, White LR. Use of the Brief Smell Identification Test for olfactory deficit in a Norwegian population with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(10):1020-1024. doi: 10.1002/gps.1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Olfactory impairment in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1170:730-735. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04013.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty RL. The Brief Smell Identification Test Administration Manual. Sensonics, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT). Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 pt 1):353-356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams DR, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, et al. Factors associated with inaccurate self-reporting of olfactory dysfunction in older US adults. Chem Senses. 2017;42(3):223-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SJ, Windon MJ, Lin SY. The association between diabetes and olfactory impairment in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019;4(5):465-475. doi: 10.1002/lio2.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohli P, Soler ZM, Nguyen SA, Muus JS, Schlosser RJ. The association between olfaction and depression: a systematic review. Chem Senses. 2016;41(6):479-486. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjw061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian Q, Resnick SM, Studenski SA. Olfaction is related to motor function in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(8):1067-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harita M, Miwa T, Shiga H, et al. Association of olfactory impairment with indexes of sarcopenia and frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(5):384-391. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purdy F, Luo Z, Gardiner JC, et al. Olfaction and changes in body composition in a large cohort of older US adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(12):2434-2440. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan Y, Luo Z, Li C, et al. Poor olfaction and pneumonia hospitalisation among community-dwelling older adults: a cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2021;2(5):e275-e282. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00083-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wehling E, Nordin S, Espeseth T, Reinvang I, Lundervold AJ. Unawareness of olfactory dysfunction and its association with cognitive functioning in middle aged and old adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26(3):260-269. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Bainbridge KE, Huedo-Medina TB, Duffy VB. Prevalence and risk factors of self-reported smell and taste alterations: results from the 2011-2012 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Chem Senses. 2016;41(1):69-76. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glennon SG, Huedo-Medina T, Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Litt MD, Duffy VB. Chronic cigarette smoking associates directly and indirectly with self-reported olfactory alterations: analysis of the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(6):818-827. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noel J, Habib AR, Thamboo A, Patel ZM. Variables associated with olfactory disorders in adults: A U.S. population-based analysis. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;3(1):9-16. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee WH, Wee JH, Kim DK, et al. Prevalence of subjective olfactory dysfunction and its risk factors: Korean National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e62725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park DY, Kim HJ, Kim CH, Lee JY, Han K, Choi JH. Prevalence and relationship of olfactory dysfunction and tinnitus among middle- and old-aged population in Korea. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordin S, Brämerson A, Bende M. Prevalence of self-reported poor odor detection sensitivity: the Skövde population-based study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124(10):1171-1173. doi: 10.1080/00016480410017468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Shrestha S, Huang X, et al. ; Health ABC Study . Olfaction and incident Parkinson disease in US white and black older adults. Neurology. 2017;89(14):1441-1447. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinto JM, Schumm LP, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, McClintock MK. Racial disparities in olfactory loss among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):323-329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joseph T, Auger SD, Peress L, et al. Screening performance of abbreviated versions of the UPSIT smell test. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):1897-1906. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09340-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Rassi E, Mace JC, Steele TO, et al. Sensitivity analysis and diagnostic accuracy of the Brief Smell Identification Test in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(3):287-292. doi: 10.1002/alr.21670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Z, Luo Z, Huang X, et al. Self-reported versus objectively assessed olfaction and Parkinson’s disease risk. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1789-1795. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaffe K, Freimer D, Chen H, et al. Olfaction and risk of dementia in a biracial cohort of older adults. Neurology. 2017;88(5):456-462. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Medical Conditions and Self-reported Olfaction at the Olfaction Sub-Study

eFigure 1. Sample Selection and Participation of the Olfactory Sub-Study

eFigure 2. B-SIT Score Distribution in the Olfaction Sub-Study (2018-2019), by Self-Reported Olfaction at the Third Follow-Up of the Sister Study (2014-2016)