Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To summarize the published literature regarding pelvic organ prolapse, dehiscence or evisceration, vaginal fistula, and dyspareunia after radical cystectomy and to describe the management approaches used to treat these conditions.

METHODS

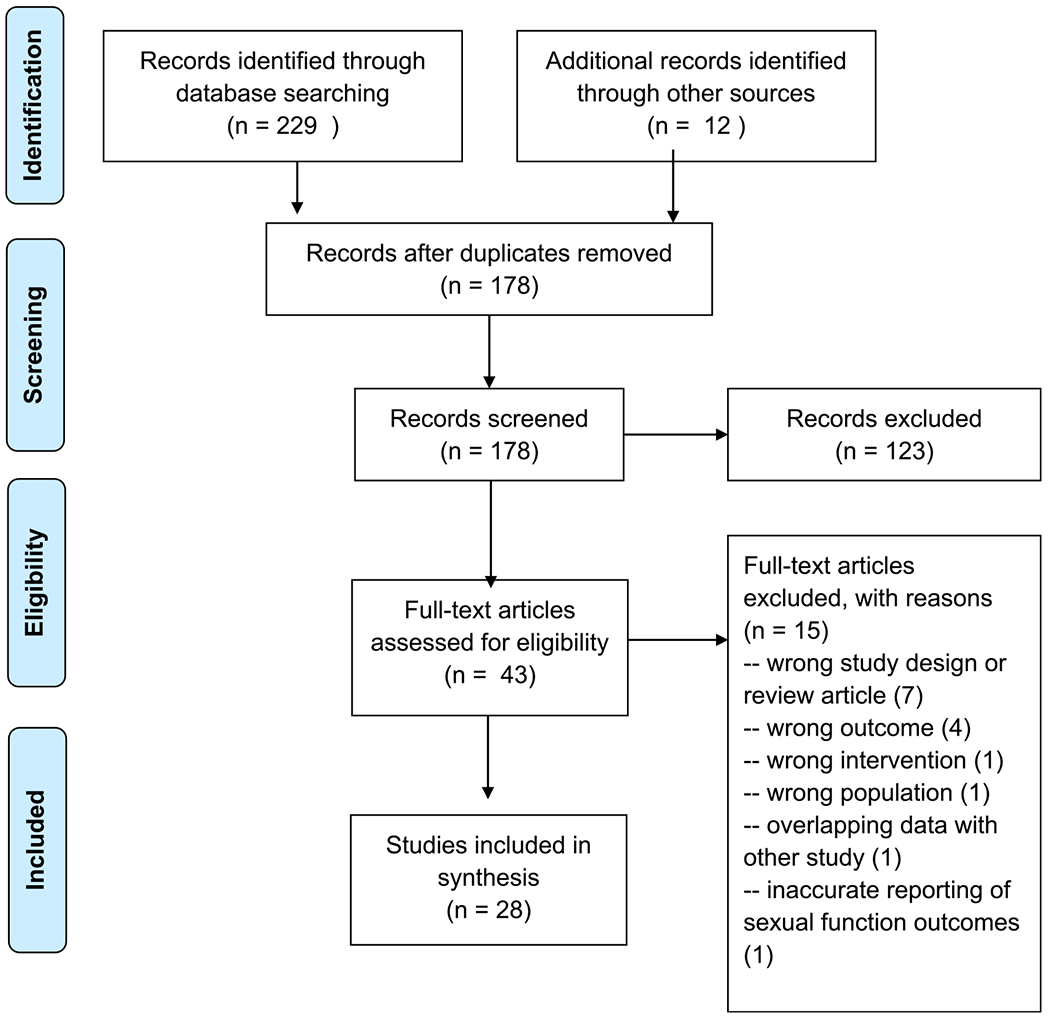

Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, and Web of Science were systematically searched from January 1, 2001 to January 25, 2021 using a combination of search terms for bladder cancer and radical cystectomy with terms for four categories of vaginal complications (prolapse, fistula, evisceration/dehiscence, and dyspareunia). A total of 229 publications were identified, the final review included 28 publications.

RESULTS

Neobladder vaginal fistula was evaluated in 17 publications, with an incidence rate of 3 – 6% at higher volume centers, often along the anterior vaginal wall at the location of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis. Sexual function was evaluated in 10 studies, 7 of which utilized validated instruments. Maintaining the anterior vaginal wall and the distal urethra appeared to be associated with improved sexual function. Pelvic organ prolapse was assessed in 5 studies, only 1 used a validated questionnaire and none included a validated objective measure of pelvic organ support.

CONCLUSION

There is a need for more prospective studies, using standardized instruments and subjective outcome measures to better define the incidence of vaginal complications after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer, and to understand their impact on quality of life measures.

Improvement in life expectancy after radical cystectomy (RC) for bladder cancer has allowed for increased focus on issues related to cancer survivor-ship.1,2 This has resulted in modifications to the standard RC technique with a goal of preserving reproductive and sexual function. However, radical cystectomy with a vaginal sparing or genital organ sparing (GOS) approach may be associated with complications specific to the female population: pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal dehiscence or evisceration, vaginal fistula, and dyspareunia. While case series of these individual complications have been reported, the actual incidence remains unknown. More importantly, no published reviews have focused on vaginal outcomes after RC.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY OF GENITAL ORGAN SPARING RADICAL CYSTECTOMY

Radical cystectomy (RC) is the standard treatment of non-metastatic muscle invasive bladder cancer or high risk non muscle invasive bladder cancer. For women, RC has traditionally included removal of the anterior vagina, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, in addition to the bladder and urethra. The female urethrectomy, was originally considered necessary for oncologic cure, as the extent of transitional cell carcinoma extension to the female urethra was poorly understood.

Although male orthotopic reconstruction with urethral preservation became a standard operation in the mid 1990’s, it was not until 2001 that Stenzl,3 demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach for women. Research found the risk of secondary tumors in the remnant female urethra to be 2% or less and demonstrated that primary tumor involvement of the bladder neck was the key risk factor for secondary urethral recurrence.4 These findings led urologists to recommend urethral-sparing cystectomy for appropriately selected women.

Further surgical modifications have been developed. The term “vaginal sparing cystectomy” describes RC with preservation of the anterior vaginal wall, which is likely to be curative in certain populations, and demonstrates benefits with respect to sexual function and continence in women with orthotopic reconstruction.5 The term “genital organ sparing (GOS) cystectomy” describes RC with preservation not only of the anterior vaginal wall but also of the uterus/cervix and sometimes tubes/ovaries if present. GOS cystectomy, because of less extensive dissection around the uterus and vagina withpreservation of the autonomic nerves, the periurethral fascia and pubourethral ligaments has been shown to improve continence in women with orthotopic reconstruction.6 The purposes of this review are (1) to summarize the published literature regarding pelvic organ prolapse, dehiscence or evisceration, vaginal fistula, and dyspareunia after vaginal sparing radical cystectomy and (2) to describe the management approaches used to treat these conditions.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

A medical librarian (E.A.) was consulted to develop a systematic search of the literature. Inclusion criteria for the review included all relevant English-language cohort studies, case control studies and randomized trials published between January 1, 2001 and January 25, 2021. Review articles and editorials were excluded. Studies reporting on the use of RC for non-bladder malignancies and benign conditions were also excluded.

Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, and Web of Science were searched using the following search terms: (‘urinary bladder neoplasms’ OR ‘bladder cancer’ OR ‘bladder carcinoma’ OR ‘uroepithelial carcinoma’) AND (‘urinary diversion’ OR cystectomy OR ‘radical cystectomies’ OR ‘radical cystectomy’ OR neobladder) AND (‘vaginal fistula’ OR dyspareunia OR enterocele OR ’vaginal dehiscence’ OR ‘vaginal evisceration’ OR ‘vaginal pain’ OR ‘vaginal atrophy’ OR ‘vaginal burning’ OR ‘vaginal discomfort’ OR ‘vaginal dryness’ OR ‘pelvic organ prolapse’ OR ‘vaginal vault prolapse’ OR ‘rectocele’ OR sexuality OR ‘sexual dysfunction’) AND (women OR female* OR woman OR vagina*). The search utilized database-specific subject headings where appropriate. The complete search strategies for each database are shown in Appendix I. A total of 229 publications were identified through database searching, and an additional 12 abstracts were added after manually reviewing reference lists of relevant review articles.

The citations were combined in Endnote and reviewed manually for duplicates, resulting in the exclusion of 63 articles. 2 reviewers (L.R. and J.E.) screened the titles and abstracts independently using the Rayyan abstract screening tool, resulting in the exclusion of 123 articles. The full text of the remaining 43 articles was reviewed independently by 2 authors for inclusion. 15 articles were excluded due to issues with study design, outcomes reporting, and choice of intervention or population. The final review included 28 publications. (Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Results were categorized based on outcomes of interest: vaginal prolapse, vaginal fistula, vaginal evisceration/dehiscence, and sexual function. Due to heterogeneity of outcomes and lack of prospective studies, meta-analysis could not be performed. Binomial 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated when not reported by the original publication.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

Neobladder-Vaginal Fistula

The incidence of neobladder vaginal fistula (NVF) was evaluated in 17 studies. 2 studies included the same NVF cohort,7,8 therefore the larger, more recent publication was utilized in analyzing this outcome, for a total of 16 studies. If a manuscript reported on both women and men, only female patients were included in the denominator to calculate incidence on NVF. The majority of patients were in their late 50s or early 60s. However, some genital-organ-sparing (GOS) cystectomy cohorts included patientsin their late 40s.9

Incidence.

The NVF rate ranged from 0 – 33.3%. However, the 33.3% (calculated 95% CI: 1 – 91%) occurred in a study of only 3 patients, where 1 of these patients developed NVF.10 The largest study reported on 249 female patients who underwent cystectomy and orthotopic neobladder (ONB) at a single institution.11 In this series, the rate of NVF was 5.6% (calculated 95% CI: 3 – 9%), diagnosed at a mean time of 4.2 months after cystectomy. Of note, these surgeons routinely performed omental interposition and prophylactic sacrocolpopexy at the time of RC in this cohort. The majority of these fistulas (10/14) occurred at the level of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis, with a smaller percentage (4/14) that developed elsewhere along the anterior vaginal wall.11 Several other of the larger studies reporting on cohorts of 192, 97 and 78 patients reported NVF in 3.1% (calculated 95% CI: 1 – 7%),12 3.1% (calculated 95% CI: 1-9%),8 and 9% (calculated 95% CI: 4-18%),13 respectively. Some, but not all, of these patients had vaginal sparing procedures. Taken together, the incidence of NVF following cystectomy varies from 3 – 6% at higher volume centers, and most often occurs along the anterior vaginal wall at the location of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis.

Risk Factors.

Risk factors for development of NVF are thought to include poor vascularity of anterior vaginal wall, intraoperative injury to anterior vaginal wall, overlapping suture lines between the vaginal cuff closure and the neobladder-urethral anastomosis, prior pelvic radiation, and local cancer recurrence.11 Several modifications have evolved in an attempt to decrease the risk of NVF.

GOS cystectomy is thought to reduce NVF by preserving the blood supply to the anterior vagina and avoiding overlapping suture lines. In 2002 Chang et al14 reported on 25 women who underwent RC with orthotopic diversion, 21 of whom had vaginal sparing procedures. They reported 1 fistula that occurred in a patient who had anterior vaginal wall injury intraoperatively, for an overall incidence of 5%.

In 2008, Lin et al15 studied 14 patients who underwent laparoscopic RC with ONB. 5 of these patients (36%) had GOS surgery, and the rate of NVF was 7.1% (it was not reported whether fistula occurred in the setting of GOS surgery). That same year, Granberg et al16 published a series of 59 patients, with 54 vaginal sparing procedures. 2 of the 54 (3.7%) who had vaginal sparing procedures developed a fistula compared to 1 of the 5 patients with RC (20%). Later, Badawy et al13 reported on 78 female patients, 9 of which had GOS cystectomy. The NVF rate was 9%, and no patients who had GOS surgery developed NVF. Finally, in 2012, Anderson et al17 published on a cohort of 51 patients, with 84% receiving GOS cystectomy. Their overall rate of NVF was 6%.

As a comparison, several large cohorts of patients who underwent standard RC demonstrated NVF in 3.1 – 5.6%, suggesting a similar incidence to that reported with vaginal sparing cohorts.8,11,12 However, a clear relationship between genital sparing RC and NVF could not be made because of significant heterogeneity between studies, including sample size, surgical approach,and variability in surgical techniques (especially placement of interposition flaps). Thus, further study is needed to establish whether the incidence of NVF is decreased in patients undergoing GOS versus standard RC.

Several groups have described interposition of mesentery or omental flaps at the time of RC as a method to reduce the incidence of NVF when a vaginal sparing approach is used. Flack et al18 utilized mesentery as an interposition flap and observed no cases of NVF (0/14), despite having 2 patients who had an injury to the anterior vaginal wall. Rosenberg et al11 performed an omental transfer interposition flap with each RC and ONB, resulting in a NVF rate of 5.8%. Overall, placement of interposition flaps makes intuitive sense but prospective data is needed to determine if this decreases the rate of NVF.

Few studies examined the role of other risk factors, such as prior radiation therapy orlocal recurrence on the incidence of NVF. This represents another area in need of further investigation.

Timing/Repair.

NVF appears to occur as a relatively early complication following RS. Specifically, the vast majority of studies reported the diagnosis of NVF within three months of initial surgery.8,12–14,19 In the remaining studies that reported on this outcome, time to diagnosis was as early as three weeks,15 and up to 7 months post operatively.16 The largest study in this review, with nearly 250 female patients undergoing RC and ONB, reported median time to diagnosis of 4.2 months.11

Eleven of the 16 studies that evaluated NVF commented on management. Nine of these included some degree of detail on the surgical repair performed to address the NVF.8,10–13,15–17,20 The majority of NVF were repaired vaginally. Fistulas that occurred high in the vaginal vault were generally repaired transabdominally with an omental interposition flap.13 Repair of these fistulas is technically difficult, with varying degrees of success. In some cases, despite multiple attempts at repair, the patient continued to have some degree of incontinence, prompting conversion to an incontinent diversion. Anderson et al17 had 3 total NVF in their cohort of 51 patients. 1 of these ultimately required conversion to ileal conduit. Another study of 78 patients reported on 7 NVF.13 4 of these were repaired vaginally with a Martius flap and three were repaired transabdominally utilizing an omental flap. 1 of the patients who initially underwent vaginal repair was converted to incontinent diversion due to persistent incontinence following repair. In a retrospective study from 2020, Lee et al20 reported on their cohort of 136 female patients with a total of 12 NVF (8.8%). Initial repair was performed transvaginally, with excision of the fistula tract and primary closure of the neobladder and anterior vaginal wall. This initial repair was successful in 10/12 cases. The other 2 patients had a recurrence at 3.2 and 14.8 months, and both received a repeat repair using the same technique. 1 of the patients had a third recurrence approximately 6 months later and underwent a third repair that was successful.

In the study by Rosenberg et al of 250 women, there was a total of 14 NVF.11 13 opted for surgical correction. Eight underwent vaginal repair with a 2-layer closure and tissue interposition. 3 of these patients ultimately had another diversion due to persistent incontinence despite successful repair. Prior to conversion to incontinent diversion, they each underwent a mid-urethral sling, without improvement in their incontinence. This highlights the importance of recognizing fistula recurrence, even following what appears to be a successful repair. At the end of the study period, 5/13 patients with NVF retained their ONB. In summary, initial repair using a transvaginal technique seems to be the most common approach to treating NVF. Further study is needed to elucidate the success rates of NVF repair.

VAGINAL PROLAPSE

Prolapse after RC was evaluated in 5 studies (Table 1). All manuscripts were retrospective cohort studies.

Table 1.

Cohort studies measuring prolapse outcomes

| First Author | Study Design | Incidence | Timing of Prolapse | Standardized Instrument; Outcome | Diversion Type | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali-El Dein, B; 2002 | Retrospective | 16/163 (9.8%) | Within 3mos after RC* | NA | ONB† | Neobladder vaginal prolapse resulted in chronic urinary retention |

| Badawy, A 2011 | Retrospective | 5/78(6%) | Within 3mos after RC | NA | ONB | Neobladder vaginal prolapse resulted in chronic urinary retention |

| Chang, S 2002 | Retrospective | 0/25 (0%) | NA | NA | ONB | Authors hypothesize that preservation of anterior wall and pubo-urethral ligaments prevented prolapse |

| Lipetskaia, L 2019 | Retrospective | 8/35 (22.8%) | Mean 6.3 years after RC | POPDI-6‡ | ONB | |

| Roshdy, S 2016 | Retrospective | 0/22 (0%) | Mean 48mos after RC | NA | ONB |

Radical Cystectomy

Orthotopic Neobladder

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory 6

Incidence

The incidence of prolapse among women specifically undergoing vaginal sparing RC could not be determined due to lack of detail in the primary sources, therefore incidence for all women underging RC is reported. 2 of the 5 papers reported no cases of postoperative prolapse at median follow-up time of 12mos and 48mos.14,21 The other 3 studies reported the incidence of prolapse after RC to be 6% at mean follow-up time of 62mos,13 10% at mean follow-up time of 36mos,7 and 23% at mean follow-up time of 6.3 years.22 The largest study with a sample size of 163 identified 16 (10%) patients with postoperative prolapse.7

There was heterogeneity in the diagnosis and identification of prolapse. Only 1 study used a validated instrument (POPDI-6) to assess subjective symptoms of prolapse.22 Another study used videourodynamics at mean follow-up of 36mos to evaluate for prolapse during voiding.7 This study defined prolapse as any herniation of the posterior neobladder pouch wall into the vaginal canal. However no objective measurements or subjective outcomes were reported. Badawy et al.13 defined prolapse as pouch protrusion through the vaginal canal on physical exam. Similarly, no objective measurements or subjective outcomes were reported. Lipetskaia et al22 in a retrospective cohort study, identified 64 post cystectomy patients and asked them to complete a demographic survey and POPDI-6 questionnaire. 35 women (response rate of 55%) completed the third question of the POPDI-6 (“Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in the vaginal area”) at a mean time of 6.3 years after RC. Eight of the 35 post cystectomy patients responded “yes” to sensation of bulge.

Urinary retention has been reported as a complication of prolapse after RC with urinary diversion. In 4 of the 5 articles describing vaginal prolapse after RC, urinary diversion was achieved with a neobladder. 1 article did not comment on the type of urinary diversion performed at time of RC.22 Several studies identified vaginal prolapse, with descent of the posterior neobladder wall into the vagina and associated acute angulation of the neobladder-urethral junction, as a cause for chronic urinary retention in women with neobladders, eg Badawy,13 noted prolapse on vaginal exam in 5 (6%) of patients, and all of these women had chronic urinary retention treated with clean intermittent catheterization. In another study, videourodynamics documented vaginal prolapse in 16 (10%) of patients, all of whom had elevated post-void residuals.7 They noted that reduction of the vaginal prolapse with a patient finger or pessary led to improved voiding with minimal post-void residual.

Prevention and Management

2 studies reporting no prolapse after RC cited preservation of the anterior vaginal wall and pubourethral ligaments, as well as limiting dissection around the vaginal apex and lateral vaginal margins, as techniques for preventing vaginal prolapse (Roshdy et al. 24 patients, mean followup 2 years and Chang et al. 25 patients, mean followup 1 year).14,21 Another study describing 5 cases of prolapse in 78 women (6%)suggested prolapse may have occurred because anterior fixation of the neobladder to the pubis or Coopers ligament was not performed at time of RC in these patients (however it was not specified what percent of cases without prolapse had anterior fixation).13 Other studies discussed surgical revision in cases with vaginal prolapse and chronic urinary retention. These cases focused on modifications to increase the posterior support of the neobladder by performing a ventral suspension of the neobladder near the dome. One paper described that ventral suspension was achieved with fixation of the neobladder to the anterior abdominal wall at the back of the rectus muscle.7

EVISCERATION

2 studies reported on the incidence of evisceration. A retrospective 2019 study reported on 100 women undergoing laparoscopic RC.23 Seven of these underwent emergent reoperation for vaginal dehiscence with bowel evisceration. Alternatively, in a retrospective study from 2020, rate of evisceration was 0% using robot assistance in a cohort of 11 patients receiving genital organ sparing RC.9 A 2019 case series described 5 cases of vaginal dehiscence and/or evisceration in women who had previously undergone robotic-assisted radical cystectomy.24 The systematic search identified 3 additional case reports or series, reporting a combined total of 7 cases of this complication.25–27 The literature is too limited to determine risk factors for this complication, however it has been hypothesized that surgical factors (length of anterior vaginal wall resection, surgical approach, excessive use of electrocautery) and patient factors (age and vaginal atrophy) may be contributers.23

SEXUAL FUNCTION

Sexual function was evaluated in women after RC in 10 studies (Table 2). Seven studies assessed sexual function using a standardized instrument: 6used the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI),9,28–32 and one used the EORTC - QLQ-BLM30.33 Sample sizes were small and ranged from 11 to 110 female patients. Some studies compared a “nerve sparing” technique, with preservation of the neurovascular bundles on the lateral walls of the anterior vagina, to a more traditional surgical approach. Due to the heterogeneity among studies assessing sexual function with respect to sample size, outcome measure, surgical approach, and diversion type, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

Table 2.

Cohort studies measuring sexual function outcomes

| First Author, year | Study Design | Number women; type RC | Diversion type | % Sexually Active | % Dyspareunia | Global sexual function score | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali-El Dein, B 2013 | Prospective | 12 GOS* compared to 41 standard RC† | ONB‡ | 11/12 (91.7%) GOS patients | NA | Mean FSFI§ = 18 +/− 1 | FSFI results better in GOS compared to standard RC group |

| Badawy, A 2011 | Retrospective | 78(9 GOS; 59 standard RC) | ONB | 65/78 (83%) | 7/65 (11%) | NA | 45/65 (69%) reported sexual dysfunction (non validated) |

| Bhatt, A 2006 | Retrospective | 13 (6 GOS compared to 7 non nerve sparing RC) | ONB | 6/6 (100%) nerve sparing; 1/7 (14%) non nerve sparing | Mean FSFI pain domain score = 4.6 +/− 0.3 to 1.5 +/− 0.5 non nerve sparing; 4.2 +/− 0.7 to 3.7 +/− 0.9 nerve sparing | Mean FSFI = 11 non nerve sparing; Mean FSFI nerve sparing = 22 | |

| Booth, B 2015 | Retrospective | 71 (46 respondents; 65% response rate); standard RC | 5 ONB, 39 conduit, 2 continent diversion | 37% active after RC (78% sexually active before RC) | Median FSFI pain domain score = 0 (range 0 – 6) | Median FSFI = 4.8 (1.2 – 32) | |

| El Bahnasawy, B 2011 | Retrospective | 73; standard RC | ONB, conduit, and continent diversion | 54/73 (74%) | 48% reported dyspareunia | Mean FSFI = 11.3 ± 7.4 | ONB FSFI scores higher than other diversions |

| Henningsohn, L 2003 | Prospective, control group | 110 | ONB, conduit, and continent diversion | NA (although reduced intercourse frequency in 19% ONB and conduit patients; 20% continent diversion patients | NA | NA | 13% ONB and 5% conduit patients reported substantial distress due to vaginal problems during sex |

| Moursy, E 2016 | Retrospective | 18; GOS | ONB | 15/18 (83.3%) | 3/18 (16.6%) | NA | All premenopausal women |

| Siracusano, S 2018 | Prospective | 33 | Conduit | NA | NA | Mean EORTC-BLM-30¶ = 23.3 (sd 24.5); Mean EORTC QLQ-C30# score sexual functioning = 7 (+/−20.3) and sex life = 75 (+/−50) | |

| Tuderti, G 2020 | Retrospective | 11; GOS | ONB | 8/11 (72.7%) | FSFI median pain domain score = 5.2 (0 – 6). | Median FSFI = 26.2 (6.8 – 33) | |

| Zippe, C 2004 | Prospective | 34 (27 sexually active and included in analysis); GOS | ONB (10), continent diversion (7), conduit (10) | 13/27 (48%) | 6/27 (22%) | Mean modified IFSF** (10 item) = 10.6 +/−6.62 |

Genital Organ Sparing.

Radical Cystectomy.

Orthotopic Neobladder.

Female Sexual Function Inventory.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer - Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire.

Index of Female Sexual Function.

The FSFI questionnaire uses 19 questions across six domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain), with a global maximum score of 36.34 Global FSFI scores lower than 26 suggest sexual dysfunction. Five studies used the FSFI scores at 12 months postoperatively to assess sexual function.9,29–32 4 studies compared patients FSFI at baseline to scores at 1-year postoperatively.9,29,31,32 1 study evaluated FSFI just at 1 year postoperatively and asked patients to reflect on how this differed from their pre-surgical function.30

Findings from these studies suggest that 37 – 100% of women are sexually active after RC. Of those, 11 – 48% report dyspareunia. Sexual dysfunction (FSFI < 26) is reported in 4 of the 5 studies that used this standardized instrument (Table 2). In considering the surgical modifications that could impact sexual function, authors focused on several surgical techniques, including preservation of anterior vaginal wall (thereby conserving vaginal length), preservation of the distal urethra (when oncologically sound) to preserve clitoral neurovasculature, and the type of urinary diversion performed. In most cases, sample sizes were small and allocation to surgical treatment arm could be biased by factors that would influence sexual function, such as extent of the tumor. Limitations in study size, retrospective study design, heterogeneity in procedures performed, and lack of validated questionnaires were found across studies evaluating sexual function which restricted ability to summarize data.

Surgical Risk Factors

In a comparison of RC techniques, Bhatt et al.29 compared postoperative sexual function between 6 women undergoing nerve-sparing RC with ONB to 7 undergoing non-nerve sparing RC with ONB (performed by a different surgeon). 1 year postoperatively, all patients in the nerve sparing group had returned to sexual activity, while only 1 patient in the non-nerve sparing group was sexually active. Additionally, the nerve sparing group had a mean FSFI score of 22.3, compared to a mean score of 11.0 in the non-nerve sparing group.

Another study using a nerve sparing, GOS technique with robotic approach for RC and ONB evaluated patients at baseline and 1 year postoperatively with the FSFI.9 1 year after surgery, 8 of 11 patients (72.7%) were sexually active. Median FSFI scores declined from a baseline of 31.9 (26.3 – 33) before surgery to 26.2 (6.8 – 33) 1 year later. With regards to single domains, while there was an initial decline at 3 months, the FSFI domains of arousal and orgasm made a complete recovery at 1year. Domains of lubrication, satisfaction, pain, and global FSFI scores remained significantly lower than baseline at 1 year postoperatively.

In 1 of 4 prospective studies, Ali-El-Dein et al28 compared sexual function in 11 of 15 women who underwent GOS RC with ONB to 110 of 290 women undergoing traditional RC. The technique was described as both vagina and nerve sparing, and the majority of patients were able to maintain their uterus. The GOS group was of young age, all less than 55 years old, the comparison group had mean age of 53 (range 23 – 73). GOS patients had earlier return to sexual intercourse (on average at 6 weeks postoperatively as compared to 14 weeks postoperatively respectively). The GOS group also had significantly higher postoperative FSFI scores overall (mean score 18 +/−1; compared to 14 +/−1 in the traditional RC group), as well as in each of the 6 FSFI domains: pain, arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction. In summary, in this small series, genital and nerve sparing techniques were associated with significantly higher FSFI scores, although many women were lost to follow up and baseline characteristics of the groups (such as age) differed.

Diversion type has also been considered as a surgical variation that might impact sexual function. Booth et al30 evaluated 41 women with the FSFI 1 year after non-nerve sparing open RC with removal of the upper third of the vagina. They reported a median FSFI score of 4.8 one year after cystectomy, indicating significant sexual dysfunction. The highest FSFI score was seen in the domain of satisfaction, which reflects on closeness with partner and overall 6 life. They observed that patients with an ileal conduit diversion had a lower FSFI score than those with a continent diversion or ONB. However, given the small sample size, tendency could not be estimated. The authors postulated that improved scores with ONB could have been influenced by the fact that more vaginal length is spared during this approach. Similarly, El Bahnasawy,31 assessed 73 women 1 year after non-nerve sparing RC with removal of the upper third of the vagina. Women were of mean age 52 +/− 6.5 years and all had undergone female circumcision during childhood. Mean FSFI preoperative score was 18.3 +/− 5.1 and this dropped to 11.3 +/− 7.4 (P<0.001) at one year postoperatively. FSFI scores at 1 year were noted to be significantly better among women with ONB diversion, as compared to non-orthotopic diversions.

In contrast, in a 2004 study designed to assess whether type of diversion affected sexual dysfunction, Zippe et al32 compared baseline and follow-up FSFI data from 27 sexually active women who underwent RC with either ileal conduit (10, 37%), orthotopic neobladder (10, 37%), or continent diversion (7, 26%). Surgery preserved the vagina and was described as nerve sparing. Only 13 (48%) of the 27 patients were able to have successful vaginal intercourse after RC. This study utilized the FSFI short version, which contains 10 questions across the same 6 domains. Domains of lubrication and ability to achieve orgasm, as well as overall score showed significant decreases after RC. There were no differences in scores between the pre and postmenopausal groups. Of the 3 types of diversions evaluated, ileal conduit was associated with the lowest postoperative sexual function scores. No statistically significant difference in sexual function was found between the ONB group and those with continent cutaneous diversions. Despite small numbers, this data suggested that preservation of the anterior vaginal wall did not result in improved sexual function after RC.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review of vaginal complications after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer was able to identify only a small number of relevant studies. These studies are largely retrospective and significant heterogeneity in surgical technique and outcome measures preclude meta-analysis. Our review suggests that neobladder vaginal fistula was the outcome most frequently studied, evaluated in 17 publications. The incidence of NVF following RC varies from 3% – 6% at higher volume centers, and most often occurs along the anterior vaginal wall at the location of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis. Sexual function was evaluated in women after radical cystectomy in ten studies, 7 of which utilized validated instruments. It was repeatedly noted that maintaining the anterior vaginal wall (with neovascular preservation) and the distal urethra (with clitoral neurovasculature preservation) appeared to be associated with improved sexual function, but differences in potential confounders and the small number of women studied prevent any definitive conclusions. Whether the type of urinary diversion influences rates of sexual function remains unclear. Pelvic organ prolapse was assessed in 5 studies, only one used a validated questionnaire and none including a validated objective measure of pelvic organ support. Few conclusions could be made about the incidence of prolapse or the level of bother, given the lack of validated outcomes. This review highlights a clear need for more prospective studies, using standardized instruments and subjective outcome measures to better define the incidence of vaginal complications after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer, and importantly, to understand their impact on quality of life measures.

Abbreviations:

- GOS

genital organ sparing

- NVF

neobladder vaginal fistula

- ONB

orthotopic neobladder

- RC

radical cystectomy

APPENDIX 1. Database Search Strategies

Database(s): Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to January 25, 2021

| Search Strategy: | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | exp Urinary Bladder Neoplasms/ | 55305 |

| 2 | (bladder adj3 cancer).ti,ab. | 36278 |

| 3 | (bladder adj3 carcinoma).ti,ab. | 13042 |

| 4 | (uroepithelial adj3 carcinoma).ti,ab. | 20 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 67966 |

| 6 | (radical adj3 cystectomy).ti,ab. | 7591 |

| 7 | exp Urinary Diversion/ | 15183 |

| 8 | exp Cystectomy/ | 9073 |

| 9 | neobladder.ti,ab. | 1728 |

| 10 | post-radical cystectomy.ti,ab. | 27 |

| 11 | radical cystectomies.ti,ab. | 181 |

| 12 | 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 | 25640 |

| 13 | exp Vaginal Fistula/ | 4853 |

| 14 | exp Dyspareunia/ | 2191 |

| 15 | dyspareunia.ti,ab. | 4074 |

| 16 | exp Hernia/ | 77068 |

| 17 | enterocele.ti,ab. | 596 |

| 18 | (vagina* adj3 (dehiscence or evisceration or fistula or pain or atrophy or burning or discomfort or dryness)).ti,ab. | 4437 |

| 19 | exp Pelvic Organ Prolapse/ | 12340 |

| 20 | pelvic organ prolapse.ti,ab. | 5474 |

| 21 | vaginal vault prolapse.ti,ab. | 476 |

| 22 | rectocele.ti,ab. | 1204 |

| 23 | exp Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/ | 30575 |

| 24 | exp Sexuality/ | 42632 |

| 25 | 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 | 172110 |

| 26 | exp Women/ | 37519 |

| 27 | exp Female/ | 8894919 |

| 28 | gender.ti,ab. | 330918 |

| 29 | vagin*.ti,ab. | 118030 |

| 30 | female.ti,ab. | 721607 |

| 31 | women.ti,ab. | 1006638 |

| 32 | exp Vagina/ | 35985 |

| 33 | exp Genitalia, Female/ | 255561 |

| 34 | 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 | 9269440 |

| 35 | 5 and 12 and 25 and 34 | 152 |

| 36 | limit 35 to (english language and yr=“2001-Current”) | 81 |

| 37 | limit 36 to “review articles” | 17 |

| 38 | 36 not 37 | 64 |

| 39 | limit 38 to (comment or editorial or letter) | 2 |

| 40 | 38 not 39 | 62 |

Database(s): Embase Classic+Embase 1947 to 2021 January 25

| Search Strategy: | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | exp bladder cancer/ | 74641 |

| 2 | urinary bladder neoplasms.ti,ab. | 87 |

| 3 | (bladder adj3 cancer).ti,ab. | 53333 |

| 4 | (bladder adj3 carcinoma).ti,ab. | 18128 |

| 5 | (uroepithelial adj3 carcinoma).ti,ab. | 28 |

| 6 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 | 91469 |

| 7 | exp cystectomy/ | 31270 |

| 8 | (radical adj3 cystectomy).ti,ab. | 13357 |

| 9 | exp urinary diversion/ | 16739 |

| 10 | neobladder.ti,ab. | 2996 |

| 11 | post-radical cystectomy.ti,ab. | 82 |

| 12 | radical cystectomies.ti.ab. | 369 |

| 13 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 | 43709 |

| 14 | (vagina* adj3 (fistula or evisceration or pain or atrophy or burning or discomfort or dryness)).ti,ab. | 7639 |

| 15 | exp cystovaginal fistula/ | 3713 |

| 16 | exp rectovaginal fistula/ | 3400 |

| 17 | exp vaginal injury/ | 670 |

| 18 | neobladder-vaginal fistula.ti,ab. | 39 |

| 19 | exp dyspareunia/ | 10880 |

| 20 | dyspareunia.ti,ab. | 7851 |

| 21 | exp pelvic organ prolapse/ | 23567 |

| 22 | pelvic organ prolapse.ti,ab. | 11057 |

| 23 | exp enterocele/ | 1015 |

| 24 | enterocele.ti,ab. | 1106 |

| 25 | exp vaginal vault prolapse/ | 1325 |

| 26 | vaginal vault prolapse.ti,ab. | 950 |

| 27 | exp rectocele/ | 2928 |

| 28 | rectocele.ti,ab. | 2391 |

| 29 | exp sexual dysfunction/ | 90041 |

| 30 | sexual dysfunction.ti,ab. | 17230 |

| 31 | sexuality/ | 42037 |

| 32 | sexuality. ti,ab. | 23071 |

| 33 | 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 | 171641 |

| 34 | exp female/ | 10195093 |

| 35 | female.ti,ab. | 1151565 |

| 36 | women.ti,ab. | 1435821 |

| 37 | woman.ti,ab. | 324155 |

| 38 | vagin*.ti,ab. | 182344 |

| 39 | exp vagina/ | 51730 |

| 40 | transvag*.ti,ab. | 22008 |

| 41 | exp female genital system/ | 484567 |

| 42 | female genitalia.ti,ab. | 2044 |

| 43 | 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 | 10746301 |

| 44 | 6 and 13 and 33 and 43 | 238 |

| 45 | limit 44 to (english language and yr=“2001-Current”) | 200 |

| 46 | limit 45 to conference abstract status | 78 |

| 47 | 45 not 46 | 122 |

| 48 | limit 47 to (editorial or letter or “review”) | 23 |

| 49 | 47 not 48 | 99 |

Database: Web of Science

2021 January 25

TOPIC: ((‘urinary bladder neoplasms’ OR ‘bladder cancer’ OR ‘bladder carcinoma’ OR ‘uroepithelial carcinoma’) AND (‘urinary diversion’ OR cystectomy OR ‘radical cystectomies’ OR ‘radical cystectomy’ OR neobladder) AND (‘vaginal fistula’ OR dyspareunia OR enterocele OR ’vaginal dehiscence’ OR ‘vaginal evisceration’ OR ‘vaginal pain’ OR ‘vaginal atrophy’ OR ‘vaginal burning’ OR ‘vaginal discomfort’ OR ‘vaginal dryness’ OR ‘pelvic organ prolapse’ OR ‘vaginal vault prolapse’ OR ‘rectocele’ OR sexuality OR ‘sexual dysfunction’) AND (women OR female* OR woman OR vagina*))

Refined by: DOCUMENT TYPES: (ARTICLE)

Timespan: 2001-2021. Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESC

68 results

REFERENCES

- 1.Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamid ARAH, Ridwan FR, Parikesit D, Widia F, Mochtar CA, Umbas R. Meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to radical cystectomy alone in improving overall survival of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. BMC Urol. 2020;20. 158–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenzl A, Jarolim L, Coloby P, et al. Urethra-sparing cystectomy and orthotopic urinary diversion in women with malignant pelvic tumors. Cancer. 2001;92:1864–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenzl A, Draxl H, Posch B, Colleselli K, Falk M, Bartsch G. The risk of urethral tumors in female bladder cancer: can the urethra be used for orthotopic reconstruction of the lower urinary tract? J Urol. 1995;153:950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein JP, Grossfeld GD, Freeman JA, et al. Orthotopic lower urinary tract reconstruction in women using the kock ileal neobladder: updated experience in 34 patients. J Urol. 1997;158:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole EE, Smith JA Jr. Orthotopic urinary diversion in the female patient. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38:25–29. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali-El-Dein B, Gomha M, Ghoneim MA. Critical evaluation of the problem of chronic urinary retention after orthotopic bladder substitution in women, J Urol. 2002;168:587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali-el-Dein B, Shaaban AA, Abu-Eideh RH, el-Azab M, Ashamallah A, Ghoneim MA. Surgical complications following radical cystectomy and orthotopic neobladders in women. J Urol. 2008;180:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuderti G, Mastroianni R, Flammia S, et al. Sex-sparing robot-assisted radical cystect omy with intracorporeal padua ileal neobladder in female: surgical technique, perioperative, oncologic and functional outcomes. J Clin Med. 2020;9:577–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horenblas S, Meinhardt W, Ijzerman W, Moonen LFM. Sexuality preserving cystectomy and neobladder: initial results. J Urol. 2001;166:837–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg S, Miranda G, Ginsberg DA. Neobladder-vaginal fistula: the university of southern California experience. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:1380–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abol-Enein H, Ghoneim MA. Functional results of orthotopic ileal neobladder with serous-lined extramural ureteral reimplantation: experience with 450 patients. J Urol. 2001;165:1427–1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badawy AA, Abolyosr A, Mohamed ER, Abuzeid AM. Orthotopic diversion after cystectomy in women: a single-centre experience with a 10-year follow-up. Arab J Urol. 2011;9:267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang SS, Cole E, Cookson MS, Peterson M, Smith JA Jr. Preservation of the anterior vaginal wall during female radical cystectomy with orthotopic urinary diversion: technique and results. J Urol. 2002;168:1442–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin TX, Zhang CX, Xu KW, et al. Laparoscopic radical cystectomy with orthotopic ileal neobladder in the female: report of 14 cases. Chin Med J. 2008;121:923–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granberg CF, Boorjian SA, Crispen PL, et al. Functional and oncological outcomes after orthotopic neobladder reconstruction in women. BJU Int. 2008;102:1551–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson CB, Cookson MS, Chang SS, Clark PE, Smith JA Jr., Kaufman MR. Voiding function in women with orthotopic neobladder urinary diversion. J Urol. 2012;188:200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flack CK, Monn MF, Kaimakliotis HZ, Koch MO. Functional and clinicopathologic outcomes using a modified vescica ileale padovana technique. Bladder Cancer. 2015;1:73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho BC, Jung HB, Cho ST, et al. Our experiences with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy: orthotopic neobladder by the suprapubic incision method. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:766–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DH, Song W. Surgical outcomes of transvaginal neobladder-vaginal fistula repair after radical cystectomy with ileal orthotopic neobladder: a case-control study. Cancer Managet Res. 2020;12:10279–10286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roshdy S, Senbel A, Khater A, et al. Genital sparing cystectomy for female bladder cancer and its functional outcome; a seven years’ experience with 24 cases. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7:307–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipetskaia L, Lee TG, Li D, Meyer H, Doyle PJ, Messing E. Pelvic floor organ prolapse after radical cystectomy in patients with uroepithelial carcinoma. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:e501–e504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanno T, Ito K, Sawada A, et al. Complications and reoperations after laparoscopic radical cystectomy in a Japanese multicenter cohort. Int J Urol. 2019;26:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin FC, Medendorp A, Van Kuiken M, Mills SA, Tarnay CM. Vaginal dehiscence and evisceration after robotic-assisted radical cystectomy: a case series and review of the literature. Urology. 2019;134:90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stav K, Dwyer PL, Rosamilia A, Lim YN, Alcalay M. Transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair of anterior enterocele following cystectomy in females. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chhabra S, Hegde P. Spontaneous transvaginal bowel evisceration. Indian J Urol. 2013;29:139–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fort MW, Carrubba AR, Chen AH, Pettit PD. Transvaginal enterocele and evisceration repair after radical cystectomy using porcine xenograft. Female Pelvic Med Reconstruct Surg. 2020;26:19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali-El-Dein B, Mosbah A, Osman Y, et al. Preservation of the internal genital organs during radical cystectomy in selected women with bladder cancer: a report on 15 cases with long term follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatt A, Nandipati K, Dhar N, et al. Neurovascular preservation in orthotopic cystectomy: impact on female sexual function. Urology. 2006;67:742–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Booth BB, Rasmussen A, Jensen JB. Evaluating sexual function in women after radical cystectomy as treatment for bladder cancer. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Bahnasawy MS, Osman Y, El-Hefnawy A, et al. Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion in women: impact on sexual function. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zippe CD, Raina R, Shah AD, et al. Female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy: a new outcome measure. Urology. 2004;63:1153–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siracusano S, D’Elia C, Cerruto MA, et al. Quality of life in patients with bladder cancer undergoing ileal conduit: a comparison of women vs men. In Vivo. 2018;32:139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]