Abstract

Smart materials can respond to stimuli and adapt their responses based on external cues from their environments. Such behavior requires a way to transport energy efficiently and then convert it for use in applications such as actuation, sensing, or signaling. Ultrasound can carry energy safely and with low losses through complex and opaque media. It can be localized to small regions of space and couple to systems over a wide range of time scales. However, the same characteristics that allow ultrasound to propagate efficiently through materials make it difficult to convert acoustic energy into other useful forms. Recent work across diverse fields has begun to address this challenge, demonstrating ultrasonic effects that provide control over physical and chemical systems with surprisingly high specificity. Here, we review recent progress in ultrasound–matter interactions, focusing on effects that can be incorporated as components in smart materials. These techniques build on fundamental phenomena such as cavitation, microstreaming, scattering, and acoustic radiation forces to enable capabilities such as actuation, sensing, payload delivery, and the initiation of chemical or biological processes. The diversity of emerging techniques holds great promise for a wide range of smart capabilities supported by ultrasound and poses interesting questions for further investigations.

1. Introduction

Recently, there has been a growing demand for smart systems or devices that can change between defined states and respond to external stimuli in an adaptive manner. Depending on the complexity, smart systems possess mechanisms or components for sensing, memory storage, computation, energy harvesting, actuation, and communication. At large scales, a smart system can have completely embedded computers that provide some of these functionalities. However, as the length scales of operation decrease below hundreds of microns, it becomes increasingly difficult to build conventional computers and actuators onto a device. Instead, we look to alternative designs where the smart capabilities are coded not into a computer but rather into specific material properties and physical (or chemical) interactions between the components that comprise the system. Biological systems are of course the pinnacle of known smart materials, with all biological functionalities arising from a mixture of physical and chemical interactions with the environment, along with biochemical information that is ultimately encoded in DNA. However, as one looks to develop smart material systems for various scientific and technological endeavors, it can often make sense to break from biological paradigms and exploit different kinds of physical effects to achieve smart functionality.

Traditional physical systems and effects that are used for smart behavior include electric fields, magnetic fields, and light. In these cases, the underlying mechanisms are clear, and there are well-known examples of responsive systems utilizing these effects. For instance, piezoelectric materials can be used to couple mechanical motion or forces to electrical signals for feedback and sensing in smart structures,1 magnetorheological fluids can provide external control over fluid behavior such as adhesion,2 certain polymers respond to pH and temperature,3,4 and photochromic materials can be used to induce coloration in transparent optical materials in the presence of light.5

Recently, ultrasound has emerged as an alternative tool to shape and impart functionality to smart materials. Ultrasound can deliver energy remotely for sensing, actuation, or communication, and it provides several qualitative benefits over optical, magnetic, and electrical fields in many contexts. Acoustic fields can propagate through opaque or complex media with low losses, can be localized to small regions in space and time, and can be tuned more than 12 orders of magnitude in frequency to effectively couple with phenomena and objects at different time and length scales. Moreover, ultrasonic sources (frequencies above 20 kHz) and technologies form the cornerstone of many mature industries, such as healthcare and nondestructive testing, making robust sources and techniques available for adaptation to new applications.

Although ultrasound can often complement the optical, magnetic, and electrical effects used in smart systems, the physical mechanisms that can be used to enable smart functionality in ultrasonic systems have long remained unexplored. The availability of miniaturized electronics and precise light emission and detection technologies over the past few decades has led to a dominance of electronic and optical techniques in the development of smart systems. As a result, ultrasound has long been overlooked as an alternative and successful implementation of smart ultrasonic systems has lagged behind the other fields.

Nonetheless, the past few years have seen several innovations that are accelerating the adaptation of ultrasonic components for use in smart systems and materials. This trend has been supported largely by a shift toward integration of smart systems with biological systems, which benefit from the above-mentioned advantages of ultrasound. Recent developments in fields such as drug delivery, energy harvesting, and genetic engineering have identified new systems triggered by ultrasound that can be adapted for use in more general smart systems. In this article, we review recent progress in this field and provide an introduction to the different key ultrasonic techniques, their implementations, and their capabilities.

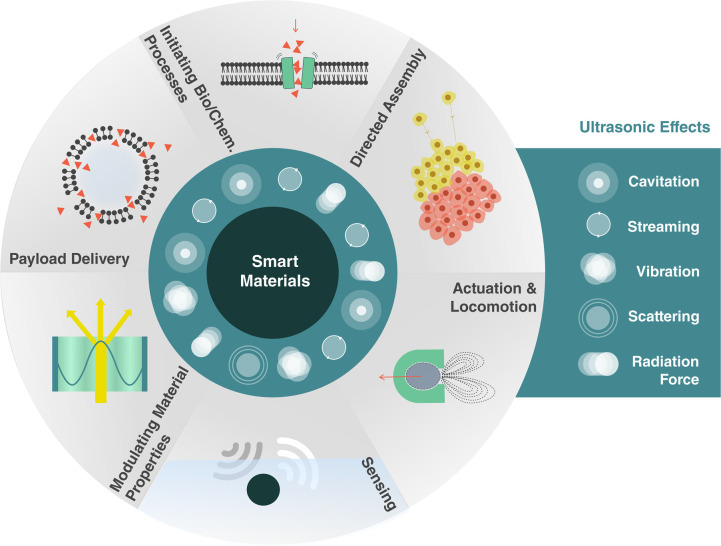

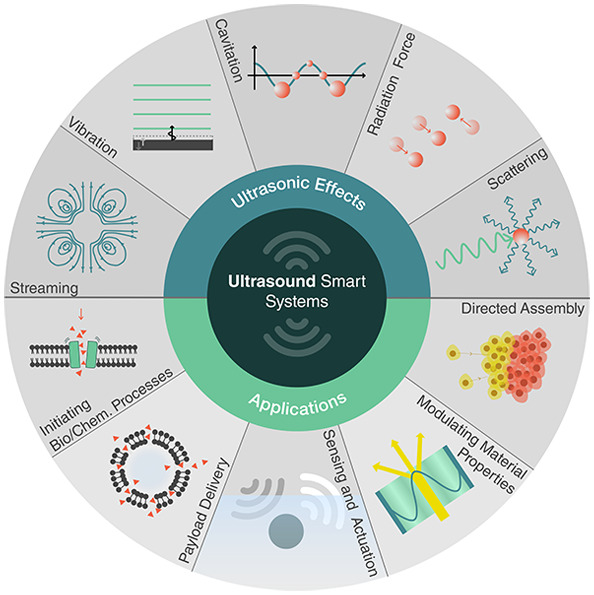

We consider how ultrasound can support six classes of smart capabilities, depicted in Figure 1. These range from directed assembly of smart materials, geometric reconfiguration of smart systems, sensing and actuation, payload transport and delivery, to the triggering of biological and chemical processes. These capabilities are enabled by different ultrasound-induced effects, namely, cavitation, microstreaming, structural vibrations, acoustic scattering, and the acoustic radiation force. This review explores the basis of these effects and how they can be utilized, tuned, and combined with other physical, chemical, and biological systems to enable unique responsive systems and smart material capabilities.

Figure 1.

Capabilities of smart materials enabled by ultrasound.

This review complements other recent reviews on subfields of acoustics (e.g., acoustofluidics,6 nanoacoustics,7,8 particle manipulation,9,10 and microbubble acoustics11) in both scale and scope. It is not restricted to any particular scale or single mechanism within acoustics. Rather, it aims to bring together all of the recent developments that can be applied in the development of smart and responsive systems. It focuses on the intersection of acoustics with smart systems and not only identifies mechanisms and techniques that could be useful for smart systems, but also explores emerging directions and open questions in this rapidly developing field.

2. Background: Acoustics and Ultrasound

2.1. What Are Acoustic Waves?

The field of acoustics deals with the transfer of energy through matter via mechanical waves. Generally, an acoustic wave is excited in a medium using a transducer, which converts electrical signals into vibrations that are transferred to the medium. These vibrations propagate through the medium as mechanical waves of compression and expansion. For many applications, it is necessary to understand how these waves will interact with any boundaries or objects that may be present. Ultimately, we want to use these underlying principles to describe and predict how acoustic waves will (1) transport energy or information to a recipient, such as a sensor, actuator or responsive material, and (2) how that information or energy can be converted into other forms of useful work.

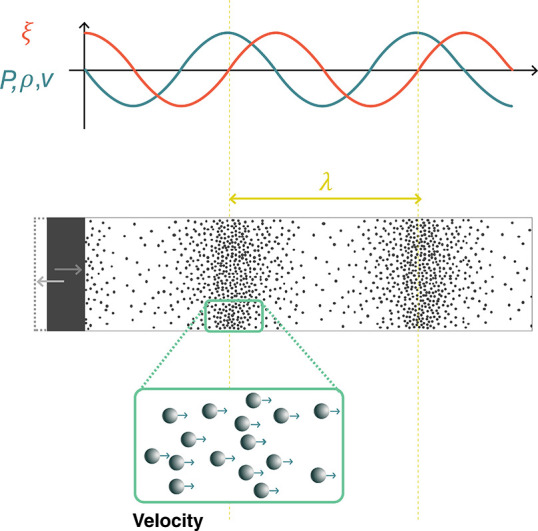

Acoustic waves carry energy through compression and microscopic motion in a medium. While the acoustic waves are ultimately reliant on intermolecular interactions, it is easier to consider the wave causing motion of conceptual small bodies or “particles” in the medium, which represent a region much larger than the atoms or molecules but small enough that the wave behavior is effectively constant within. The acoustic wave can then be described continuously through the medium using different acoustic quantities: the pressurep, particle velocityv⃗, particle displacement ξ⃗, and density fluctuation ρ. As is seen below, these quantities can ultimately be used interchangeably, depending on the problem at hand. As a wave propagates, the acoustic quantities will vary in time and with the position in the medium, as shown in Figure 2. While it is possible to describe the propagation of a wave, it is common to refer to the shape of an acoustic field, which means the values of p, v, ξ, or ρ at every point in space, and usually indicates an interest in spatial patterns associated with the wave.

Figure 2.

Acoustic waves generated by the motion of a boundary. Acoustic waves are mechanical waves of compression and rarefaction in a medium. Within the wave, the local pressure p, density ρ, particle velocity v, and particle displacement ξ vary as a function of time and position, with specific relationships between these variables. Density, pressure, and velocity oscillate in phase, while the displacement is 90° out of phase.

Acoustic waves are typically excited in a medium by a moving boundary. For instance, ultrasonic transducers use piezoelectric materials to convert electrical energy into mechanical vibrations. This oscillating boundary motion creates regions of high density (compression) and low density (rarefaction) that travel outward from the transducer, as shown in Figure 2. In the compressed regions pressures are higher than ambient pressure, while in the regions of rarefaction they are lower. Since the pressure varies in space, there is a net force in any given region of material, driving the local particle velocity.

An acoustic excitation travels through the material with a finite speed c, known as the material’s sound speed. In a fluid, the sound speed depends on the fluid’s equilibrium density ρ0 and its adiabatic bulk modulus K:12

| 1 |

In solids, wave propagation is more complicated because, in addition to compressional interactions, elastic solids also support shear interactions. Such shear coupling leads to a large number of different wave types that can propagate in solids, depending on geometry and mechanical properties. In the simplest case of an infinite (or very large) solid body, two types of waves can propagate: bulk compressional (longitudinal) and shear (transverse) waves. Their propagation speeds are given by

| 2 |

| 3 |

where G is the solid’s shear modulus. When interfaces are present, then additional wave types may propagate, including Rayleigh waves at an interface, flexural waves in a plate, and axial and torsional waves in bars, among others. In many cases, acoustic wave propagation in solids can be approximated considering only compressional wave behavior. This simplification is most accurate when waves propagate at normal incidence through a solid. Below, we will only consider acoustic waves in fluids and ignore elastic wave effects. A complete treatment of elastic waves can be found in standard texts.13 As indicated by eq 1, the stronger the bulk modulus (and thus the intermolecular forces), the higher the sound speeds: solids tend to have higher sound speeds than liquids, which in turn tend to have higher sound speeds than gases. (While the density suggests that the lower density of gases would increase the sound speed compared to solids, the bulk modulus changes more and, therefore, has a larger role in setting the sound speed.)

Most often, acoustic systems are driven harmonically, or sinusoidally at a single frequency f. In this case, p, v⃗, ξ⃗, and ρ will oscillate at the driving frequency in time, forming periodic waves in space with a wavelength λ = c/f. (This is true for small amplitude waves, but for large amplitudes or when significant nonlinearities are present, additional harmonics could arise.)

While acoustic waves span an enormous range of frequencies from below 1 Hz (atmospheric infrasound) to over 100 GHz (crystal lattice vibrations), this review is mainly concerned with ultrasound in the range 20 kHz–50 MHz. This range is of particular interest because these frequencies (1) fall outside the range of human hearing; (2) interact safely and with low losses in many materials including the human body; (3) have (relatively) small wavelengths in water (λ ≈ 15 mm at 100 kHz, 1.5 mm at 1 MHz, and 0.15 mm at 10 MHz), making them useful for interactions with small systems; (4) have short time scales (τ ∼ 1/f), making them useful for exchanging energy with fast phenomena; and (5) can be produced by many well-established transducer technologies across the frequency range and with large ranges of excitation pressures. Because the acoustic displacements themselves are rather small at high frequencies, it is instead often the very high accelerations associated with ultrasound that can drive strong effects in microscale systems.14

Depending on the system that is being analyzed, it is convenient to convert between the different acoustic quantities described above. These properties can be related to each other explicitly depending on the wave geometry. In most cases of interest, the wavefronts are planar and propagate in one direction (like those illustrated in Figure 2). In this case the acoustic quantities are related by12

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

where  is the imaginary unit. Equation 4 is derived from the equation

of state of the material and indicates that the acoustic density fluctuations

ρ are in phase with the acoustic pressure p: regions of high pressure correspond to compression in the medium

and regions of low pressure correspond to rarefaction as described

previously. For a plane traveling wave p and v are in phase as well, a fact that changes for curved wavefronts

or close to interfaces. The particle motion ξ associated with

the wave is proportional to the particle velocity, but 90° out

of phase. Moreover, the particle displacement decreases as the acoustic

frequency f increases for a fixed pressure. A p = 10 kPa plane wave in water causes particle motions of

1 nm at 1 MHz and 10 nm at 100 kHz, while a 1 MPa plane wave at those

frequencies causes motions of 100 nm and 1 μm, respectively.

By contrast, the density fluctuation and particle velocity are frequency

independent. A 10 kPa pressure wave in water is associated with a

particle velocity of v = 6.75 mm s–1 and a relative density change of ρ/ρ0 = 4

× 10–6. At 1 MPa, v = 675

mm s–1 and ρ/ρ0 = 4 ×

10–2.

is the imaginary unit. Equation 4 is derived from the equation

of state of the material and indicates that the acoustic density fluctuations

ρ are in phase with the acoustic pressure p: regions of high pressure correspond to compression in the medium

and regions of low pressure correspond to rarefaction as described

previously. For a plane traveling wave p and v are in phase as well, a fact that changes for curved wavefronts

or close to interfaces. The particle motion ξ associated with

the wave is proportional to the particle velocity, but 90° out

of phase. Moreover, the particle displacement decreases as the acoustic

frequency f increases for a fixed pressure. A p = 10 kPa plane wave in water causes particle motions of

1 nm at 1 MHz and 10 nm at 100 kHz, while a 1 MPa plane wave at those

frequencies causes motions of 100 nm and 1 μm, respectively.

By contrast, the density fluctuation and particle velocity are frequency

independent. A 10 kPa pressure wave in water is associated with a

particle velocity of v = 6.75 mm s–1 and a relative density change of ρ/ρ0 = 4

× 10–6. At 1 MPa, v = 675

mm s–1 and ρ/ρ0 = 4 ×

10–2.

As was described above, acoustic waves carry energy, which can be used to perform useful work. The energy density carried by a plane wave is given by12

| 7 |

where P and V are the acoustic pressure and velocity amplitudes.

Another commonly used metric for describing energy propagation in a wave is the wave intensity, which quantifies the rate of energy transfer by the acoustic wave (in units of W cm–2). The time average intensity for a plane wave in a fluid can be calculated directly from the pressure and fluid properties:

| 8 |

The strength of an acoustic field is sometimes reported as a pressure and sometimes as an intensity, depending on the application or conventions in a research field. Therefore, it is valuable to be able to convert between these two descriptions. Moreover, because energy must always be conserved, eq 8 is a useful tool to estimate pressure amplitudes in different systems, such as when sound is transmitted from a material with one set of material properties (ρ0, c) into another (ρ0′, c′). Similarly it helps to estimate the pressure produced by a transducer emitting a power W from an active area A. In this case, the intensity should scale as I ∼ W/A, which allows us to estimate the pressure generated in the propagation medium with (ρ0, c). Exemplary values for acoustic pressure and intensity in water are given in Table 1 as a reference, since most of the systems described in this review occur in an aqueous environment.

Table 1. Relationship between Acoustic Intensity and Pressure for Plane Waves in Water.

| pressure | intensity |

|---|---|

| 1 kPa | 3.3 × 10–5 W cm–2 |

| 10 kPa | 3.3 × 10–3 W cm–2 |

| 100 kPa | 0.33 W cm–2 |

| 1 MPa | 33 W cm–2 |

After considering how acoustic waves carry energy through materials in the form of pressure, density, and local velocity fluctuations, we will discuss how different materials and geometries impact the acoustic response of a system and the associated energy transfer.

2.2. Controlling Acoustic Waves

2.2.1. Acoustic Properties of Materials

The acoustical and geometrical properties of a medium dictate how effectively energy can be transported between two points. This also opens up opportunities to control the wave and energy propagation by structuring materials appropriately. Commonly, a material’s acoustic properties are described by its acoustic impedance Z = ρ0c, which describes the resistance of a medium to move given a fixed pressure excitation (see eq 5). A high-Z material will exhibit smaller particle velocity for a fixed excitation pressure. Conversely, a fixed vibration amplitude of a surface (such as a transducer) will produce lower pressures in a low-Z material. The acoustic impedance determines the behavior of waves at the interface between different media. If an acoustic wave is incident on a flat interface between two media with impedances Z1 and Z2, sound will reflect backward from the interface with a reflection coefficient:

The fraction of the incident

energy

reflected back from the interface is given by |R|2. Acoustic waves couple more efficiently from one medium to

another if their impedances are similar, so R →

0. The acoustic impedance therefore determines how strongly acoustic

waves are scattered or reflected from an interface, and this can have

important implications when designing acoustic systems such as resonators

or when trying to control materials with sound, e.g., using the acoustic

radiation force, as will be seen below. As a reference, the values

of ρ0, c, and Z are provided for some common materials in Table 2. To improve acoustic transmission between

highly disparate media, as often encountered in transducer design,

matching layers can be used. For example, ideal transmission can be

achieved between two interfaces by adding a thin layer between them,

with impedance  and thickness λ3/4 (where

λ3 = c3/f). The thickness constraint restricts this concept to work only in

a narrow frequency band. In practice, two or more consecutive matching

layers are often used to provide more robust broadband matching. Alternatively,

broadband matching layers have been reported using gradient-index

metamaterials, which are structures with subwavelength features that

change the bulk properties for acoustic waves (cf. gradient index

materials in optics).15

and thickness λ3/4 (where

λ3 = c3/f). The thickness constraint restricts this concept to work only in

a narrow frequency band. In practice, two or more consecutive matching

layers are often used to provide more robust broadband matching. Alternatively,

broadband matching layers have been reported using gradient-index

metamaterials, which are structures with subwavelength features that

change the bulk properties for acoustic waves (cf. gradient index

materials in optics).15

Table 2. Acoustic Properties of Selected Materials at Room Temperature (20 °C)a.

| material | ρ (kg m–3) | c (m s–1) | Z (Pa s m–1) | a (dB cm–1) | notes | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| air | 1.2 | 343 | 412 | – | 20 °C | (12) |

| water | 997 | 1482 | 1.5 × 106 | 2.2 × 10–3 | at 100 kHz | (18, 19) |

| 0.22 | at 1 MHz | (19) | ||||

| brain tissue | 1035 | 1562 | 1.6 × 106 | 0.58 | at 1 MHz, 37 °C | (20) |

| bone | 1990 | 3198 | 6.4 × 106 | 3.54 | at 1 MHz, 37 °C | (20) |

| glycerol | 1260 | 1904 | 2.4 × 106 | – | (21) | |

| silicone oil | 818 | 960 | 0.8 × 106 | – | Dow 200, 1 cSt viscosity | (21) |

| PDMS | 1031 | 1028 | 1.1 × 106 | 0.4 | at 3 MHz | (22) |

| PMMA | 1191 | 2690 | 3.2 × 106 | 0.7 | at 1 MHz | (23) |

| silica glass | 2200 | 5900 | 13 × 106 | – | (24) | |

| brass | 8470 | 4494 | 38 × 106 | – | C38500 alloy | (24) |

ρ, density; c, sound speed; Z, impedance; a, attenuation coefficient.

An additional important material property when designing acoustic systems is the material attenuation coefficient. Attenuation describes the loss of acoustic energy irreversibly to heat through various mechanisms such as viscosity or molecular relaxation.12 When an acoustic wave propagates in material, the pressure amplitude after a distance L is given by p = p0e–αL, where p0 was the initial pressure of the wave and α is the attenuation coefficient in neper per centimeter. More commonly, the attenuation coefficient is expressed as a = 8.7α, which is given in units of decibels per centimeter. Attenuation depends strongly on frequency, and higher frequencies are attenuated more strongly than low frequencies. Empirical models typically describe this dependence as a power law: a(f) = a0fγ, where 0 < γ ≤ 2. To describe a material’s attenuation at all frequencies, it is therefore sufficient to know the value of a at one frequency, the frequency at which a was measured, and the power γ. For liquids including water γ = 2,16 while for many polymers including PMMA the relation is almost linear (γ ≈ 1).17Table 2 provides the attenuation coefficient a and measurement frequency for a few select materials.

2.2.2. Effects of Geometry on Acoustic Waves

In addition to the choice of material, a material’s geometry can also be used to control the propagation of acoustic waves. Ultrasound transducers are typically designed to emit plane waves, as shown in Figure 3a. When a plane wave is incident on the interface between two different materials, part of the energy will be reflected and part will be transmitted, as described above. When the interface is planar, the transmitted portion of the wave will bend, or refract, as shown in Figure 3b. Refraction depends on the sound speeds of the two media and the angle of incidence: stronger refraction will take place between two media with very different sound speeds. A nonplanar interface will lead to more complex refraction and reflection and, therefore, can produce more complex acoustic fields. For example, a curved interface can be used to focus acoustic waves, as shown in Figure 3c. While lenses are commonly designed for use in transmission as depicted here, it is also possible to use a curved reflective surface to focus sound as well. Refraction is not inherently frequency dependent; however, when curved interfaces are used, the focusing properties will depend on the relative magnitude of the focal length and the wavelength, making lenses frequency dependent. For a fixed lens geometry, higher-frequency ultrasound can be focused to a smaller spot than lower-frequency ultrasound.

Figure 3.

Methods to shape ultrasound fields. (a) A simple piston transducer approximately produces a plane wave in a uniform medium. (b) When the plane wave transmits into a medium of a different sound speed, refraction causes the wave direction and wavelength to change. (c) A lens can be used to focus plane waves to a point. (d) An acoustic hologram provides more control to turn a plane wave into an arbitrarily shaped pressure field. (e) A resonator can be built to create a high-amplitude patterned pressure field using two opposing transducers or a transducer and a reflector.

Recently, powerful techniques have been developed to shape acoustic fields using acoustic holograms, as shown in Figure 3d.25 Acoustic holograms use algorithmically designed interfaces to shape an incident acoustic plane wave so that it forms a desired (and arbitrary) field shape after a certain propagation distance. Acoustic holograms have been used to create pressure fields patterned with very high complexity, and they can be tailored to each specific application much more flexibly than a conventional focusing element such as a lens. Similar to lenses, acoustic holograms can be designed for use in transmission geometries (as depicted) or in reflection, and the resolution of the features that can be produced increases with the frequency.

Interface geometry also plays an important role when more complex wave types are used. Surface acoustic waves (SAW) are waves that propagate only at interfaces between two media and can be used to confine and guide energy along a specific path, which is finding increasing application in microscale devices.14 When at least one of the media is solid, then the interface geometry can also strongly determine what kinds of waves can be reflected. In some cases, the geometry can prevent certain kinds of elastic or surface waves from being generated, while in other cases it can be used to efficiently convert energy between different propagating wave types.13 While such mode conversion is sometimes a source of undesired losses, it is also a common technique used when designing transducers to excite specific kinds of waves.26 Increasingly, custom surface designs (metasurfaces) are being explored to produce specific and tunable reflection or refraction behaviors.27 However, these techniques are currently used in the audible (low-kilohertz) frequency ranges, and scaling the structures down for use at megahertz frequencies remains an open challenge.

Finally, acoustic fields can be shaped and amplified by confining them in space within a resonator. Resonators can be designed in different shapes and configurations, but the simplest resonator is a homogeneous medium between two rigid walls, separated by a distance L = nλ/2 = nc/(2f), for any integer n. Such a resonator geometry is shown in Figure 3e. Acoustic waves in a resonator propagate in both directions—either because of reflection off one wall or because of being driven by two opposing transducers. The opposite-traveling waves interfere and produce a standing wave pattern, which is fixed in space. For the best performance, it is critical that the walls are properly spaced at the resonant distance. When this condition is satisfied, constructive interference leads to a strongly amplified field in the resonator, in the form of a regular grid of high- and low-pressure regions that can be used for different applications, such as trapping and manipulation of small objects. Because the performance is dependent on the boundary spacing L, resonators are typically designed to operate at one frequency.

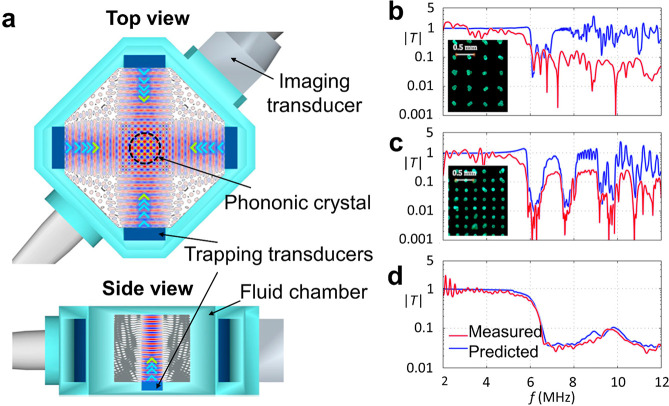

2.2.3. Bubbles

Because of their geometry and mechanical properties, gas bubbles constitute a special class of acoustic material that is used heavily in emerging ultrasound technologies. While they are not typically used to shape acoustic fields, their response to acoustic fields can be tuned and measured for different applications. Bubbles are unique acoustic objects because they can produce large acoustic and vibrational responses to sound whose wavelength is much larger than the bubbles themselves. For the description here and the discussion in the following sections, we will only consider subwavelength spherical air bubbles in water.

The mechanical properties of gas bubbles are responsible for their strong response. Gas bubbles are highly compressible and behave like a spring when excited by ultrasound: they store energy in compression and expansion cycles and release it as kinetic energy within the surrounding fluid. Bubbles are therefore resonant objects, whose response can be amplified by driving them at their resonance frequency. Resonant excitation leads to large amplitude motion of the bubble walls and a stronger scattering response for sensing. A resonant bubble can reflect over 100 times more energy than expected on the basis of its size alone.28

The fundamental resonant frequency of a bubble is known as the Minnaert frequency fM, which is set by the bubble size, properties of the gas, and properties of the fluid:28,29

| 9 |

Here, R is the bubble radius, κ is the polytropic coefficient for the gas, pA is the ambient pressure, and ρ0 is the density of the surrounding liquid. Additional factors, such as surface tension, shift the resonant frequency from this idealized value;28,30 however, the Minnaert frequency provides a good starting estimate for a bubble resonance in most cases. A 1-μm-diameter air bubble in water is resonant near 6.6 MHz; at 10 μm, the resonance drops to around 660 kHz, and at 100 μm it drops to 66 kHz.

The properties of the medium surrounding the bubble can also have a decisive effect on the bubble’s resonance. In many applications, small microbubbles are encapsulated in viscoelastic shells to stabilize them against gas diffusion. In other situations, bubbles may be embedded in a complex medium such as a gel. In these cases, the resonance frequency and resonant response will depend on the shell or medium properties as well.31 If a bubble is partially enclosed by a rigid structure, then it cannot expand symmetrically, and it will also exhibit altered resonance behaviors. When the bubble is enclosed in a cavity, higher-order interfacial resonances can be observed, where the bubble interface oscillates like a pinned membrane.32,33

Bubbles can be turned into tools by feeding them energy with an external sound field, causing the bubble to oscillate. These oscillations have two important effects. First, they can emit sound themselves (a scattered acoustic wave), creating a point source of sound that can be remotely measured. Second, they can generate strong fluid flows that can be used to apply fluid stresses to objects at the microscale and molecular scale. These streaming effects are often amplified in the presence of rigid boundaries and structures.

The strength of these different bubble responses depends primarily on the size of the bubble (which sets the resonance frequency) and the driving ultrasound frequency. For scattering, the strength is quantified by the scattering cross section of the bubble, which indicates how much of the incident energy is scattered by the bubble. At low frequencies (excitation f ≪ fM), the scattering cross section depends most strongly on the frequency, increasing as (f/fM)4. At resonance (f = fM), the cross section only depends on the resonance frequency of the bubble, scaling as fM–2 or, equivalently, as R2. The larger the bubble, the stronger its resonant response will generally be.28 The strength of streaming responses from bubble excitation is more complicated and also depends strongly on the presence of boundaries around the bubble. These effects are discussed more in sections 2.3.2 and 3.6.1. Another way to increase the response strength of a bubble is to increase the amplitude of a driving field. However, after a certain point, large vibration or pressure amplitudes will lead to nonlinear bubble oscillations34 and cavitation, which is discussed more in section 2.3.4.

Because they can convert acoustic energy into other forms of energy such as fluid flow, bubbles can also serve as sources of loss for acoustic waves. In general, bubbles will lose energy through one of three mechanisms: thermal losses during gas compression, viscous losses in the fluid, and acoustic scattering. Depending on the size of the bubble, different loss mechanisms dominate.30 For air bubbles in water that are larger than 10 μm, viscous forces are negligible, and thermal losses dominate at low frequencies while acoustic radiation dominates at high frequencies. For smaller bubbles, viscous losses become significant at low frequencies, but the high-frequency damping response is still dominated by acoustic radiation.30

2.3. Using Acoustic Energy

When ultrasound is used for smart systems, one important goal is to use the acoustic waves for nonacoustic work, such as moving objects, initiating chemical reactions, and mechanically triggering biological processes. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to convert the acoustic energy. Sometimes this is because the final action is inherently another form of work, e.g., electrical or chemical. Other times, it is because the target system cannot respond strongly to mechanical stimuli at ultrasonic frequencies. In either case, mechanisms are required that can convert the acoustic energy into a more useful form for the task at hand. In this section, we describe four mechanisms that are commonly used for this purpose: piezoelectricity (section 2.3.1), acoustic streaming (section 2.3.2), acoustic radiation forces (section 2.3.3), and cavitation (section 2.3.4).

2.3.1. Piezoelectricity

Piezoelectric materials are noncentrosymmetric materials that generate an internal electrical polarization in response to an applied mechanical stress. Consequently, the (inverse) piezoelectric effect can be used to produce motion and therefore acoustic waves from an externally applied electrical voltage. Piezoelectricity can be observed in crystals such as quartz, ceramics such as lead zirconate titanate (PZT), and polymers such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). The strength of the piezoelectric effect can be quantified by the longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient d33, which describes how much the material will deform for a given voltage. A typical value for commercial PZT is d33 = 265 × 10–12 m V–1 (PIC181, PI Ceramic, Germany). In addition to being useful for converting electricity into motion, piezoelectric materials can also convert sound into electrical signals via the direct piezoelectric effect. Beyond applications for sensing ultrasound, the direct piezoelectric effect can be used to generate voltages that can be used to trigger chemical processes and biological signaling, as discussed in section 3.

2.3.2. Acoustic Streaming

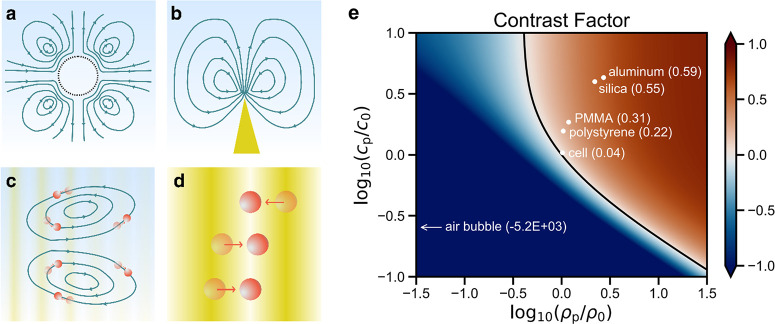

In order to directly convert high-frequency ultrasonic waves into steady forces on objects, it is necessary to make use of nonlinear acoustic mechanisms. The first nonlinear acoustic mechanism that can be used for this purpose is acoustic streaming.35 Acoustic streaming refers to fluid flow driven by acoustic waves, which is caused by momentum transfer from the acoustic waves to the fluid. This can occur at the fluid boundary layer along vibrating bubbles or structures, where the dissipation of acoustic energy due to the steep velocity gradient induces boundary layer streaming, called Schlichting streaming.36 Driven by the shear of this boundary layer streaming, there will be a flow in the bulk fluid called Rayleigh streaming, as shown in Figure 4a,b.37 Acoustic streaming can also occur in a bulk fluid because of attenuation of the propagating wave. This is known as Eckart streaming and is shown in Figure 4c.38

Figure 4.

Different mechanisms can be used to convert ultrasonic energy into other forms for useful work. (a) Bubble vibration induced streaming. (b) Microstructure vibration induced streaming. (c) Acoustic streaming induced by acoustic wave propagation and attenuation. (d) Acoustic radiation force. (e) Acoustic contrast factor as a function of particle and fluid properties, with specific values plotted for common acoustic materials in water.

Rayleigh streaming is strongest when a structure, such as a bubble or a beam, is excited on resonance, causing maximal vibrations. The resonance frequencies of elastic structures are dependent on their size, geometry, and mechanical properties. When driven by a fixed acoustic intensity, high-aspect-ratio or sharp-edged structures generally provide a stronger streaming response than low-aspect-ratio structures. The oscillation of these resonant microstructures will induce intense Schlichting streaming in the surrounding fluid boundary layer, which will generate strong Rayleigh streaming in the nearby bulk fluid.39 Rayleigh streaming can also happen when a surface acoustic waves propagate along a solid boundary, which typically has a higher frequency than the resonant microstructures.14

In the presence of acoustic streaming, any structures or particles in the flow will experience a drag force caused by the viscosity in the fluid. At small length scales, the fluid flow is typically dominated by viscous effects, and the viscous stress applied to a boundary by a fluid moving with velocity v and viscosity μ is given by τ = μ∇v⃗. The shear stress from a fluid is proportional to viscosity and to the gradient of the velocity, which is also known as the strain rate. Small objects in the flow, such as microparticles, will be carried along with the flow unless they are held in place by other forces (e.g., magnetic, electrostatic, or acoustic radiation forces). Soft structures and macromolecules, on the other hand, can be deformed by the drag forces, or even broken by them if the shear rate is high enough.40

2.3.3. Acoustic Radiation Forces

The second nonlinear mechanism that can be used to create steady forces is the acoustic radiation force (ARF).41 Acoustic radiation forces can be experienced by surfaces, structures, or microparticles exposed to ultrasonic waves (see Figure 4d). Most commonly, we will discuss the acoustic radiation force on microparticles that are much smaller than the acoustic wavelength.

For a uniform spherical particle suspended in a liquid, the ARF is dependent on the properties of both the acoustic field (i.e., the intensity and frequency) and particles (i.e., the size and acoustic properties relative to the surrounding media). Following a classic model for the acoustic radiation force,42 the ARF on an elastic spherical particle can be calculated as the gradient of a potential FARF = −∇UARF, which is in turn proportional to the particle volume V, acoustic contrast factor Φ of the particle, and the acoustic intensity I: UARF ∝ IΦV. The acoustic contrast factor measures the difference in acoustic properties between the particle and the surrounding fluid and is given by43

| 10 |

where the subscripts “p” and 0 refer to the particle and the surrounding medium, respectively. The acoustic contrast factor is plotted in Figure 4e as a function of ρp/ρ0 and cp/c0. The values of Φ for selected materials are labeled as well. As seen in the plot, the amplitude of the acoustic contrast factor—and therefore the strength of the ARF—increases as the particle and liquid become more acoustically different. For example, in the same acoustic field, the acoustic radiation force on a silica microparticle will be higher than that on a same-sized polystyrene microparticle. In comparison, a cell, which is mostly water, will experience a much lower ARF than either of the solid microparticles.

In general, materials with positive acoustic contrast (Φ > 0) move against a spatial pressure gradient and eventually accumulate in the pressure nodes (where p = 0), as shown in Figure 4d. Materials with negative acoustic contrast on the other hand are attracted to antinodes (where the pressure amplitude is maximal). Particle manipulation and directed assembly or tweezing at fixed locations can thus be achieved by carefully designing structured acoustic fields, e.g., by using a lens,44 hologram,25 diffractive element,45 or resonator.46

It should be noted that this model of the ARF only applies to simplified conditions where the particle diameter is much smaller than the acoustic wavelength of the medium and the shear acoustic waves in the particles are neglected. When these assumptions cannot be satisfied, more complex models can provide more accurate predictions for the ARF.47

A special case of ARF is experienced by bubbles in an acoustic field and can be broken into two parts: the primary and secondary Bjerknes forces.28,48,49 Primary Bjerknes forces arise on an isolated bubble in an acoustic field and are given by F⃗B1 = −V∇P, where V is the bubble volume, P is the acoustic pressure amplitude, and ∇ is the spatial gradient operator. Primary Bjerknes forces arise from slight differences in the pressure that a bubble experiences at different points in its oscillation. The primary Bjerknes force pushes bubbles toward regions of high pressure when they are excited below resonance (bubble smaller than the size resonant with driving field) and toward regions of low pressure when they are excited above resonance (bubble larger than resonant size). The secondary Bjerknes force emerges between two or more bubbles in an acoustic field, through the pressure fields scattered by each bubble. The secondary Bjerknes force can be attractive or repulsive depending on the bubble sizes and the driving frequency. Because the secondary Bjerknes force depends on the scattered field, it is shorter range and typically weaker than the primary Bjerknes force. However, when many bubbles are aggregated within a region of low pressure, such as at the nodes of a resonator, the secondary Bjerknes forces can play an important role, leading to motion, rearrangement, and clustering behavior of the bubbles. Elastic particles can experience similar secondary radiation forces based on scattered waves.50

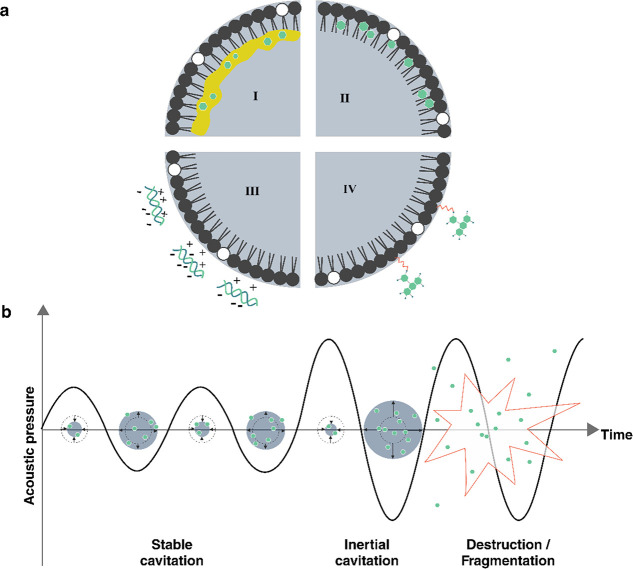

2.3.4. Cavitation

A final and important mechanism to convert acoustic energy into other forms is cavitation.51 During cavitation, an acoustic wave causes bubbles to form, oscillate, and potentially collapse in a fluid. Because of the strong response of bubbles to ultrasound, significant amounts of energy can be transferred from an ultrasound wave into bubble motion during the cavitation process. Between the large amplitude motion and the violent bubble collapse, cavitation can provide both strong mechanical and thermal stimuli. Additionally, during bubble collapse, a small plasma can form (sonoluminescence), which can also play an important role in optical and chemical processes. During bubble collapse, the temperature can briefly (<1 μs) reach several thousand kelvin and pressures on the order of tens of megapascals. These extreme conditions are associated with plasma formation in the collapsing bubble, which can produce radical species and emit electromagnetic radiation known as sonoluminescence.52

Cavitation occurs when the rarefaction (negative) pressure in an acoustic wave is low enough to draw dissolved gases out of solution into bubbles. This effect is more likely at lower frequencies, where the duration of strong negative pressure is longer each cycle than at higher frequencies. If nucleation sites are present in the fluid, such as micro- or nanoparticles, or rough surfaces, then cavitation can typically occur more easily. Similarly, if a fluid already contains microbubbles, then the effects of cavitation can be observed more easily. Conversely, cavitation effects can be suppressed by degassing the fluid.

A metric that indicates the strength of cavitation effects in aqueous systems with microbubbles is the mechanical index (MI):28

| 11 |

where Pnp is the

peak negative pressure in an acoustic wave in MPa and f0 is the frequency in MHz. While the MI is calculated

in units of  , it is commonly reported without

the units.

At low MI (MI < 0.1), microbubbles only scatter the ultrasound

signal (linear backscattering). At intermediate MI (0.1 < MI <

0.4) the bubble response becomes nonlinear, with increased scattering

at harmonic and subharmonic frequencies34 (integer multiples or fractions of the driving frequency), due to

large stable volumetric oscillations. This regime, which is referred

to as stable cavitation, can induce slow bubble destruction via diffusion

depending on the gas solubility in the surrounding medium. At higher

MI (MI > 0.4), microbubbles will violently oscillate to the point

of their collapse, emitting acoustic waves in a wide range of frequencies.

This regime is known as inertial (or unstable) cavitation.

, it is commonly reported without

the units.

At low MI (MI < 0.1), microbubbles only scatter the ultrasound

signal (linear backscattering). At intermediate MI (0.1 < MI <

0.4) the bubble response becomes nonlinear, with increased scattering

at harmonic and subharmonic frequencies34 (integer multiples or fractions of the driving frequency), due to

large stable volumetric oscillations. This regime, which is referred

to as stable cavitation, can induce slow bubble destruction via diffusion

depending on the gas solubility in the surrounding medium. At higher

MI (MI > 0.4), microbubbles will violently oscillate to the point

of their collapse, emitting acoustic waves in a wide range of frequencies.

This regime is known as inertial (or unstable) cavitation.

Different mechanical effects can be induced by ultrasound via cavitation, depending on the MI.53 The linear and nonlinear re-emission of sound at low to intermediate MI is the basis for the use as ultrasound contrast agents.54 Additionally, the increase in volumetric oscillation amplitude at intermediate MI is responsible for microstreaming flows.55 Bubble collapse at high MI may be accompanied by the emission of a shock wave.52,55 Microstreaming and collapse both will impose shear stresses on nearby structures. If the bubble is close to a surface, such as a container wall or another bubble, it can exhibit highly nonspherical oscillations that at intermediate MI values give rise to microstreaming velocities on the order of 1 mm s–1.55 At higher MI, collapsing bubbles near a surface can generate a liquid microjet that can cause damage to solid structures.

In addition to inducing mechanical effects, cavitation can also convert acoustic energy into heat.55 Three mechanisms may be involved in heat generation, depending on the size of the bubble, ultrasound parameters, and viscosity of the medium. The first one is heating of the surroundings due to the nonlinear acoustic radiation. The second effect is heating through viscous dissipation in the liquid during bubble motion. The third effect is thermal conduction through the gas core during compression of the bubbles. Heating due to nonlinear acoustic emission typically dominates in biomedical applications.55

2.3.5. High- and Low-Intensity Ultrasound

The nonlinear effects described in this section all typically require high pressures or intensities to be realized. The use of high-intensity ultrasound often comes with additional instrumentation challenges and risks for damage, e.g., in sensitive biological systems. Therefore, it is often desirable to operate with lower power acoustic systems when possible. However, there are no clear boundaries between high- and low-intensity (or power) ultrasound, and different definitions are adopted by different authors. Here, we will avoid arbitrarily defining a boundary between low- and high-intensity ultrasound, and instead we will always provide the intensity or pressure levels in our descriptions.

Nonetheless, certain metrics are still valuable reference points for high-intensity ultrasound. As described above, the mechanical index can indicate when different detrimental effects of cavitation can be expected. In addition, guidance from the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) regarding safe operating levels for medical ultrasonic devices56 is often adopted as guidelines for other applications. The FDA defines maximum allowable intensities based on the MI and two intensity metrics: the spatial-peak pulse-average intensity (ISPPA) and the spatial-peak temporal-average intensity (ISPTA). ISPPA is the time-average intensity over the duration of a pulse, whereas ISPTA is the time-average over a longer time frame, therefore applying to continuous excitation as well. The maximum allowed intensities depend on the target tissue, but maximum permissible values for peripheral vessels are defined as ISPTA = 720 mW cm–2 and ISPPA = 190 W cm–2 or a mechanical index MI = 1.9. Higher values result in a temperature increase via absorption and thus can lead to cell death above 43 °C.

In section 3, acoustic effects and properties described here will be built upon to shape, trigger, interrogate, and actuate materials.

3. Acoustic Responses for Smart Materials

3.1. Patterning and Assembly of Biological Materials

Living biological matter can be seen as a blueprint for smart materials, as it can self-organize and act in response to cues from the environment. It is therefore of interest to build new hybrid smart materials from living components, such as cells. However, patterning and assembling functioning cellular structures—let alone synthetic organs—using biological building blocks is still a major challenge.57,58 Acoustic waves are benign to cells and can be used to assemble and shape biological matter via fluid streaming or the acoustic radiation force. The resulting forces can move biological cells and push them into predefined locations. It is also possible to align and assemble different cell types into functioning cell aggregates and simple organoid-like structures. These acoustic bioassemblies are promising for biomedical research, including drug screening,59 tissue engineering,60,61 and disease modeling.62

Acoustic assembly techniques complement other techniques that have also been developed for these purposes, and they generally offer advantages for assembly in certain circumstances. For instance, optical tweezers have found widespread use in the manipulation and assembly of individual cells and small particles. A recent review by Dholakia et al.10 highlights some of the key differences between optical and acoustic techniques for manipulation. Ultrasound is shown to generally provide higher trapping forces than light, while sacrificing some of the force sensitivity and spatial precision of optical techniques. Acoustic patterning and assembly also offers the advantages of good biocompatibility, rapid and parallel control of large numbers of cells, and efficient transmission for long-range control of assembled systems.

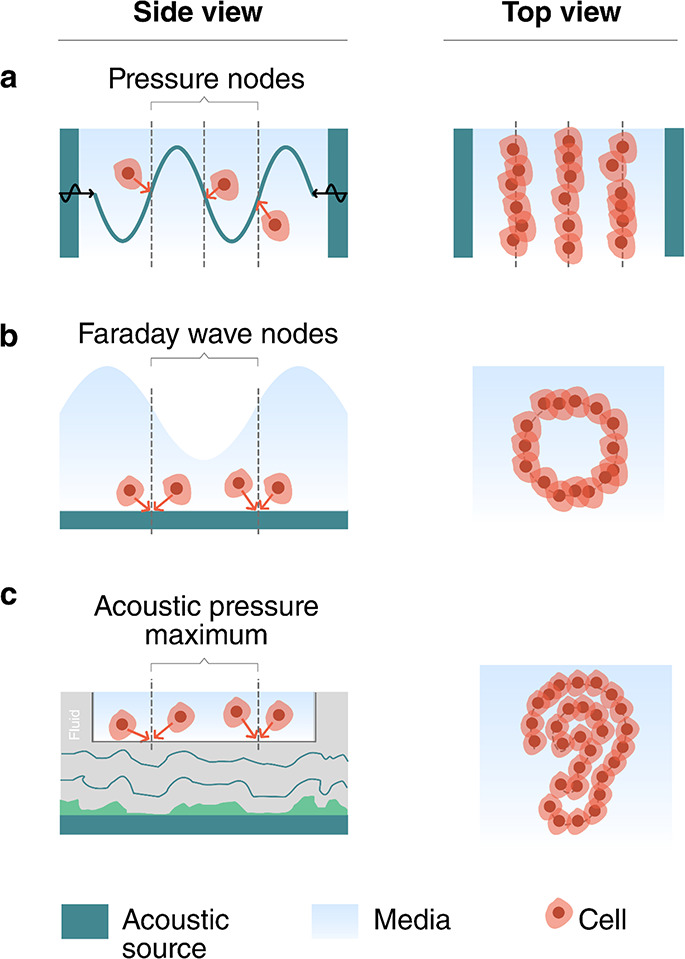

The acoustic methods that are predominantly used in the patterning and assembly of cells can be divided into three categories, as shown in Figure 5: standing wave trapping,63,64 Faraday wave patterning,65−67 and holographic patterning.68,69

Figure 5.

Acoustic patterning and bioassembly. (a) Standing wave trapping of cells in a resonator, (b) Faraday wave patterning, and (c) holographic acoustic patterning.

Standing wave trapping (Figure 5a) is based on the acoustic radiation force experienced by cells when they are exposed to a standing acoustic wave. As described in section 2.2.2, standing acoustic waves are most commonly formed by opposing pairs of acoustic sources63 or by a resonant cavity that is excited by a single acoustic source.70 The acoustic radiation forces in these systems range from ∼1 pN to ∼10 nN. Biological cells will typically be trapped at the pressure nodes and, accordingly, form highly symmetric assemblies and periodic patterns.

Faraday waves (Figure 5b) are forced surface ripples that form at the liquid–air interface of a bounded liquid. They are typically generated by low-frequency vibrations (40–200 Hz) and display a vertical surface deformation, which causes recirculating flows in the fluid. These flows can carry suspended cells via the Stokes drag toward the stagnation points, which are located below the nodes of the surface waves. Faraday waves are enhanced when the excited at resonance frequencies of the container. Cells have been assembled into simple shapes, such as periodic straight or curved lines.65

Holographic particle patterning9 (Figure 5c) uses holograms to shape the acoustic field for the assembly of cells.68 Acoustic fields can be holographically patterned using a 3D-printed holographic phase mask,25,71 a phased array transducer,72−74 or a spatial acoustic modulator.75 Unlike standing waves and Faraday waves, holographic sources can potentially shape arbitrary complex fields that are independent of the container geometry. Thus, holograms can assemble cells into nonsymmetrical and irregular patterns. Both acoustic streaming and acoustic radiation forces can be used to aggregate cells in areas of high acoustic pressure.68

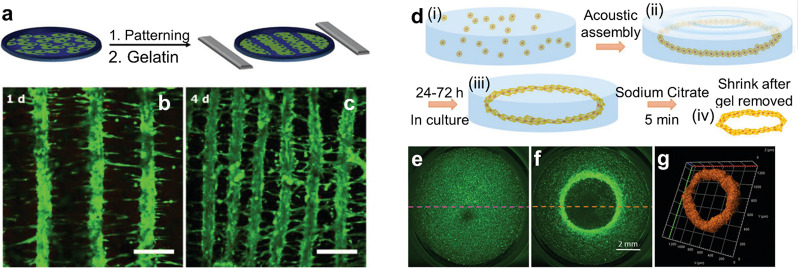

Patterning and assembling cellular structures offers the opportunity to use them as actuators and components in the development of miniaturized robotic systems.76 There has been considerable progress in using acoustic fields to align muscle cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes, myoblast cells) into tissuelike structures, which naturally actuate. Natural muscle tissue is organized along fibers, so the objective of the acoustic cell assembly is to form lines of cells. Armstrong et al.60 demonstrated acoustic assembly of myoblasts using standing acoustic waves (Figure 6a–c). Prior to the experiment the cells were suspended in a pre-cross-linked hydrogel. Then a standing pressure wave was generated between two pairs of opposing transducers to pattern the cells into periodic stripes whose pitch could be tuned by varying the frequency of the acoustic field. To immobilize the cell pattern, after assembly the hydrogel was cross-linked with UV light or slight heating. The cell patterns could then be incubated and formed tissue constructs with oriented multinucleated myotubes bundled into parallel, aligned muscle fibers. Tensile tests confirmed an increased Young’s modulus in the fiber direction. The assembled muscle tissue also responded to pulsed electrical stimulation. Ren et al.66 demonstrated the assembly of fibroblasts into ring-shaped structures using Faraday wave patterning (Figure 6d–g). The cell patterning was performed in a pre-cross-linked hydrogel (alginate), which was cross-linked after assembly with an ionic trigger (addition of calcium chloride) to immobilize the cell assembly for culturing. After 24–72 h the cells located on the outside of the ring showed radial alignment, while those on the inside showed circumferential alignment. The surrounding hydrogel could be dissolved and the cellular rings could be further assembled into tubular or concentric ring structures by using Faraday waves. The cellular assembly depends on the pattern of standing Faraday waves; thus its shape and size can be tuned by changing the container size or vibration frequency.65 This flexibility in cellular assembly could be potentially used in tuning the cell alignment and the mechanical properties of the assembly.

Figure 6.

Acoustic assembly of cells to form actuators. (a–c) Patterning of fibroblast cells into stripes by standing acoustic wave trapping. Adapted from ref (60). CC BY 4.0. (d–g) Ring-shaped cell structures via Faraday wave patterning. Adapted with permission from ref (66). Copyright 2019 Wiley-VCH.

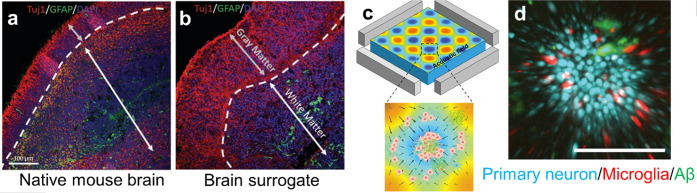

Acoustic cell assembly has also been used for the development of simple cellular models for neural and brain studies.77 Organoids assembled from preselected cell types have been used to mimic specific brain regions, such as forebrain, midbrain, and cerebral cortex. The aforementioned work of Faraday wave cell patterning66 also demonstrated the acoustic assembly of simple brain organoids (Figure 7a,b). To mimic native brain tissue, the authors separately assembled neuron-rich and astrocyte-rich cellular rings, both from E18 mouse cells. Those were placed concentrically in a medium and cultured together for 14 days. The brain surrogate presented a viability of 87% after 7 days. The neurons in this simple brain organoid model showed synchronized calcium activity, indicating the formation of a network of neurons.

Figure 7.

Acoustic assembly of neuronal and simple brain models. The bioassemblies show similar characteristics as the real organs. Native mouse brain (a) with an outer layer of neuron-rich cells and a neurite tract and a layer rich in glial cells. The acoustically assembled cells (b) exhibit similar features. Panels a and b reproduced with permission from ref (66). Copyright 2019 Wiley-VCH. (c, d) An acoustically aggregated brain organoid for Alzheimer’s disease modeling. Neuron inflammation depends on the presence or absence of amyloid-β in the environment. Reproduced with permission from ref (78). Copyright 2020 RSC Publishing.

Acoustic bioassembly can be used to build disease models of brain tissue. Cai et al.78 used standing wave trapping to aggregate brain cells (including neurons, microglia, and astrocytes) and amyloid-β aggregates (potential key contributors to Alzheimer’s disease79) into spheroids to mimic the neuroinflammation process in Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 7c,d). Compared to the control group of spheroids without amyloid-β aggregates in the environment, the disease model spheroid showed a significantly higher expression of microglia activation, which is consistent with signs of neuroinflammation.80 Acoustically assembled spheroids can therefore potentially be used as convenient in vitro models for research into Alzheimer’s and other diseases.

The patterning and assembly of cells and living tissues using acoustics offers a versatile and benign route to construct biological smart materials, such as bioactuators and (brain) organoids. There is room for improvement to increase the complexity and functionality of the bioassemblies that can be generated with acoustic fields. Also, it is known that a 3D spatial control of the distribution of cells will extend the functionality81 and facilitate the integration of the bioassemblies with artificial microstructures.82 However, 3D control has yet to be shown with acoustic methods. In addition, some studies have shown that cells can assemble into spheroids in acoustic streaming flows.83−87 The flow enriches the cell concentration at the vortex center and also disturbs the cell adherence to the container surface; thus it enhances the formation of cellular spheroids. For future studies, precise and high-throughput control of the acoustic streaming profile could open up new directions in the patterning and assembly of biological materials. Going further, more studies can be expected to investigate the influence of acoustic waves on cellular properties that are important for long-term cell patterning and assembly. Such properties include proliferation,88,89 viability,90 metabolic activity, and differentiation. Finally, the ability to select the cell type during the assembly would open up the possibility to enable vascularization in the bioassembly,91−93 which is important for larger scale structures, and to realize the growth of real organs or tissues with acoustic fields.

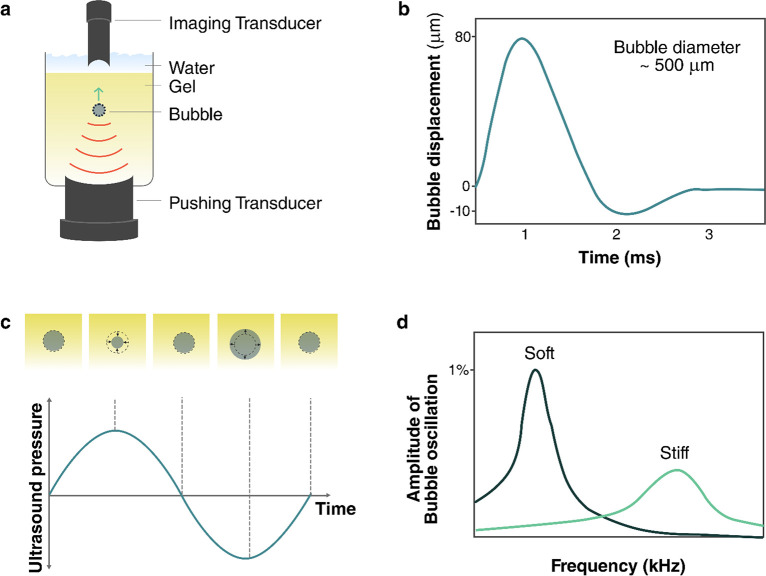

3.2. Reconfiguring Shape and Material Properties

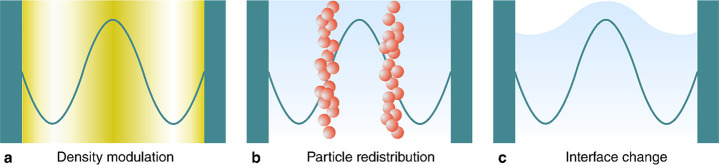

Acoustic fields can be used to change the shape and microstructure of a material, opening up pathways to control its functionality. Three physical mechanisms (Figure 8) provide a means to affect different material properties: (1) pressure waves can be used to modulate the density of a medium, (2) the acoustic radiation force on particles and molecules can be used to modify the structure and behavior of microstructured materials, and (3) the acoustic radiation force can change the geometry of interfaces. In this section we review how these mechanisms have been exploited to achieve different functionalities relevant to smart materials, focusing on examples where ultrasound has been used to control the propagation of light (section 3.2.1), the propagation of sound (section 3.2.2), and the mechanical properties of soft materials (section 3.2.3).

Figure 8.

Three physical mechanisms provide control over different material properties: (1) pressure waves can modulate the density of a medium, (2) the acoustic radiation force on particles and molecules can modify the microstructure of materials, and (3) the acoustic radiation force can change the shape of an interface.

3.2.1. Controlling Light with Sound

Smart systems can use ultrasound to control the propagation of light, e.g., for communication, computation, sensing, or power delivery. One of the biggest advantages of ultrasonic modulation in optical systems is the fast response time. For example, variable focusing techniques that rely on electrical, magnetic, or fluidic effects typically respond slower than 1 ms, whereas acoustic lenses and modulators can respond on submicrosecond time scales.94−98 Ultrasonic devices for controlling light ultimately rely on one of three fundamental mechanisms: causing spatial variations in a medium’s density, changing the shape of an optical interface, or patterning particles or orienting liquid crystals in a medium. Therefore, acousto-optic systems provide two key benefits for the development of smart materials. First, they reveal what kinds of structural and geometric changes can be controlled by ultrasound, and with what speed. Second, since the mechanisms take place at the microscale and even molecular scale, the techniques developed in optics provide insight into how smart systems could be designed to inherently manipulate light when exposed to ultrasound.

The most common acousto-optic systems rely on the photoelastic effect, whereby density changes from a pressure wave cause changes to the optical index of refraction. When light is transmitted through a region containing spatial variations in the index of refraction, the light will diffract and change its direction according to the pattern of the refractive index.99 By controlling the refractive index variations using ultrasound, light can be modulated, patterned, focused, or redirected.

The change in the index of refraction Δn is related to the acoustic wave’s intensity Iac by100

| 12 |

where n0 is the

medium’s refractive index without ultrasound applied,  is the medium’s

photoelastic constant,

ρ0 is density, and c is its sound

speed. For example, for water n0 = 1.33,

is the medium’s

photoelastic constant,

ρ0 is density, and c is its sound

speed. For example, for water n0 = 1.33,  = 0.31, ρ

= 103 kg m–3, and c =

1.5 × 103 m s–1. Acoustic waves

with an intensity of I = 10 W cm–2 will cause the optical refractive

index to change by around 0.01%,100 which

is small in absolute terms but large enough to achieve light modulation.

The photoelastic response of water (e.g., as indicated by the

= 0.31, ρ

= 103 kg m–3, and c =

1.5 × 103 m s–1. Acoustic waves

with an intensity of I = 10 W cm–2 will cause the optical refractive

index to change by around 0.01%,100 which

is small in absolute terms but large enough to achieve light modulation.

The photoelastic response of water (e.g., as indicated by the  value) is

strong compared to many optical

materials; however, solid crystals have often been preferred because

they show lower acoustic losses.101 Depending

on the specific application requirements, different materials such

as water-soluble oxides can provide both a strong photoacoustic response

and the benefits of crystalline structure.101

value) is

strong compared to many optical

materials; however, solid crystals have often been preferred because

they show lower acoustic losses.101 Depending

on the specific application requirements, different materials such

as water-soluble oxides can provide both a strong photoacoustic response

and the benefits of crystalline structure.101

The critical factors in controlling light with sound are the material properties of the propagation medium (especially the photoelastic constant and refractive index), the ultrasound intensity and frequency, and the geometry of the light-controlling system. Whereas the material properties and ultrasound intensity will affect the strength of the photoelastic response according to eq 12, the system geometry and ultrasound frequency will primarily determine how the light is scattered or redirected in any given application.

Using the photoelastic effect, different spatial patterns of sound can provide different kinds of control over light. Traditional acousto-optic modulators (AOMs) excite one-dimensional sinusoidal pressure waves in an optical medium.102,103 These variations create an optical grating that can diffract light, as shown in Figure 9a. The light can be scattered in different directions, as the grating period depends on the ultrasound frequency and amplitude. The switching rate between different states is limited only by the transit time of the sound wave through the AOM, leading to very fast modulation times, with rise times on the order of 10 ns possible.104 Depending on the optical system surrounding an AOM, the beam deflection can be used to create an optical switch,103 an optical power modulator,105 a phase modulator,96 a signal analyzer,106 a lens,105,107 or a beam deflector.108 The 1D geometry of the waves in traditional AOMs also makes it possible for ultrasound to filter the wavelength of light transmitted through the device, because of a phenomenon known as Bragg scattering.109 This capability has been used for applications in spectroscopy103 as well as communications, displays, and sensing.110,111 Additionally, the AOM can impart a small frequency shift to the incident light, which can be used for information encoding in sensing or communication applications.110,112,113 Since AOMs have been the subject of many comprehensive reviews, we direct the interested reader to standard references (refs (100−102, 105, 106, 110, 111, 114, and 115)) for more details on the design, operation, and applications of AOMs.

Figure 9.

Working principles and examples of acoustically reconfigurable optical systems. (a) Acousto-optic modulator (AOM) used to control the propagation of light via ultrasound-controlled diffraction. The device can be used to redirect light or, with additional optics as shown here, to modulate the beam intensity. (b) Working principle of a cylindrical transient acoustic grating (TAG) lens. When the acoustic field (purple) causes density changes inside the resonator, the associated index of refraction changes bring incident light to a focus. (c) The principles of a TAG lens also help to focus light through a scattering medium. Optical scattering path without and with acoustic field applied. (d) Experimental images of light propagating through a TAG filled with scatterers without (above) and with (bottom) the acoustic field applied. Panels b–d adapted from ref (120). CC BY 4.0. (e) Two liquid deforming interface lens. Reprinted with permission from ref (129). Copyright 2010 OSA Publishing. (f) Large interface deformation activated by acoustic radiation force. Reproduced with permission from ref (130). Copyright 2008 EPL Association. (g) Liquid crystal lens operating principle and physical implementation. Adapted with permission from ref (131). Copyright 2018 AIP Publishing.

The photoelastic effect can also be used in a cylindrical geometry to create an adjustable lens. When a cylindrical resonator is excited with ultrasound at the frequency of a radial resonance, the standing wave in the resonator will vary in the radial direction but not along the cylinder’s length, as shown in Figure 9b. The optical index variations that are induced in this geometry give rise to a gradient index lens, whose focusing behavior depends on the amplitude and frequency of the ultrasound. Because they can be externally controlled by ultrasound, such devices are known as tunable acoustic gradient index (TAG) lenses. TAG lenses can be used to generate nondiffractive Bessel beams116 and to provide a variable focus lens for imaging.117−122 TAG lenses are typically constructed as water- or oil-filled cylindrical resonators. When the resonator is driven continuously with ultrasound, the focusing behavior of the lens will oscillate at the ultrasound frequency, and different focal lengths can be selected by synchronizing the light source or a sensor with the acoustic waves.98,123 Such systems have been used to image objects separated by 100 mm, with submicrosecond switching speeds,97 as well as for megahertz-frequency depth scanning in optical coherence tomography.98 Driving a 38-mm-diameter resonator at resonance (832 kHz), Scopelliti and Chamanzar120 demonstrated that the focal distance could be scanned over a range of 5.4 mm and the numerical aperture could be tuned by up to 21.5%.

A powerful benefit of using photoelastic methods to control light is that they can be applied directly to media of interest for sensing or power transmission through optically scattering media. For example, it has been demonstrated when ultrasound was applied directly to a tissue phantom in a TAG geometry. As shown in Figure 9c,d, the TAG focusing counteracted the scattering losses in the tissue and made an embedded object visible.120 For more flexibility, the resonator can be driven using an eight-element transducer array, which can switch the TAG lens between different focusing modes,122 enabling adaptive light delivery through real tissue.121 Another photoelastic technique that has been used for focusing light into scattering media is known as “acoustic guide star” focusing. When light passes through a region of focused ultrasound in a scattering medium such as tissue, it becomes phase shifted by the density variations and frequency shifted by the vibrating motion of the scatterers.124 This “tagged” light creates a virtual “guide star” whose emission can be measured and reversed to compensate for the scattering effects.125 Using collapsing microbubbles as the optical scatterers in acoustic guide star focusing makes it possible to focus light to below 2 μm through a tissue sample.126 Such light focusing and tagging techniques have been explored for imaging125−127 and neuromodulation,128 and could find additional uses in sensing, power delivery, or communication through highly scattering media.

The second class of acoustically reconfigurable optical components is based on the deformation of optical interfaces, such as water/oil,129 water/air,132 or water/gel133,134 interfaces. Since light refracts at the interface of two different materials, by controlling the shape of the interface it is possible to control how light is focused. Two approaches have been explored to generate such deformations with sound. One class of device uses the acoustic radiation force generated in a resonant cylindrical geometry filled with two liquids, as shown in Figure 9e. When the acoustic cell is excited, the radiation force deforms the interface between the two media, creating a lens whose shape and thus focusing power depend on the strength of the radiation force. By tuning the driving amplitude, the lens power can be shifted on the fly, with response times in the low-microsecond range.129,133 High-intensity ultrasound can also deform fluid interfaces in other geometries,130,135 as shown in Figure 9f. However, such extreme deformations are more difficult to use for optical control. An alternative approach to interface deformation is to use hydrodynamic motion associated with higher-order resonances in a cylindrical resonator. In these tunable lenses, the piezo drives hydrodynamic flows within the liquid, which lead to static interface deformations that can be controlled by the piezo driving voltage.132

The final class of acoustically driven optics relies on structural rearrangements of particles or molecules within an acoustic field. As described in section 2.3.3, acoustic fields can impart static forces on particles within the field through the acoustic radiation force. When particles are introduced into resonator geometries, such as the cylindrical TAG lenses, they will assemble and contribute to the optical focusing effects depending on their refractive index. Early reports using TAG lenses suggested enhanced focusing performance with nanoparticles in the resonator.117 Another way to make use of the acoustic radiation force is to place liquid crystals in a resonator. In the system described by Shimizu et al.,131 liquid crystals were trapped between two glass plates inside an ultrasonic resonator and were normally oriented perpendicular to the glass through chemical interactions, as shown in Figure 9g. When ultrasound was applied, the radiation force caused the liquid crystals to twist, changing the optical index of refraction. Since the ARF was strongest in the center of the resonator, the liquid crystal alignment varied as a function of radius, creating a lens whose focal length could be tuned by the ultrasound pressure (driving voltage). Applying modest powers up to 6.5 mW, the authors reported a shift in focal length of up to 1.2 mm from the 50-μm-thick liquid crystal layer. Liquid crystals dispersed in polymer droplets have also been used as ultrasound-switched shutters in a chip-based system excited by surface acoustic waves around 20 MHz.136 As the ultrasonic wave passes through the suspension, the liquid crystals reorient and no longer scatter light, creating a transparent window. However, with a response time on the order of 10 s, this approach is much slower than other acousto-optic techniques.

3.2.2. Controlling Sound Propagation with Sound

The ability to control sound with sound is typically the domain of nonlinear acoustics, whereby high-intensity acoustic pressures alter the acoustic properties of materials enough to have an effect on the propagation of sound. Such effects can provide the ability to redirect sound137 or to generate new frequencies.138 However, nonlinear effects of sound in homogeneous media are relatively weak, because dispersion is basically absent and shock-formation processes dominate at ultrasonic frequencies of interest (<1 GHz). Reviews by Hamilton138 and Bunkin et al.139 discuss some nonlinear acoustic phenomena, often restricted to very high-intensity effects such as cavitation. Alternative approaches to achieve a strong nonlinear acoustic response, and thereby control sound with sound, have been developed based on structural effects. Examples have been demonstrated in waveguides and using combinations of highly dissimilar materials, such as ordered particle suspensions, gas bubbles in liquids, or cavities in solids.

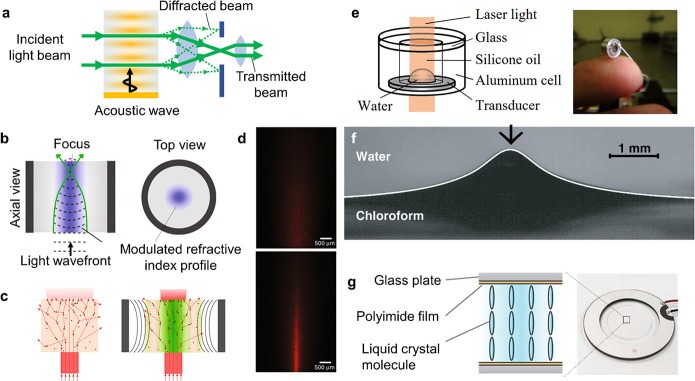

A prominent example

of such approaches is phononic crystals: materials that influence

passing sound waves due to periodic features in their structures.

Resonant inclusions in a material can block the propagation of sound

within a specific frequency range, because all the energy is effectively

trapped in the inclusion, leading to so-called band gaps. Scattering

of a wave from periodically spaced features can similarly lead to

constructive or destructive interference that depends on the feature

spacing and the orientation. Phononic crystals guide or shape sound

waves in unusual ways, and in this section it is seen how ultrasound

can be used to modulate such behavior dynamically. For instance, Caleap

and Drinkwater140 demonstrated how a reconfigurable

phononic crystal can be obtained by assembling microparticles into

a regular grid with the acoustic radiation force. Figure 10a shows a schematic of the

setup, where the combined sound fields of three perpendicular standing

waves formed a periodic grid of trapping sites in the center. The

trapped particles assembled into a tetragonal crystal, where the lattice

spacing could be tuned via the wavelength of the trapping field, in

this case  and az = λz/2. The properties of

the phononic crystal can thus be changed in a dynamic and reconfigurable

way. In this example, band gaps appeared in the acoustic transmission

spectrum of a broadband ultrasound pulse traversing the crystal. The

authors realized crystals at 2.25, 3.75, and 5.25 MHz of which 2.25

and 3.75 MHz are shown in panels b and c, respectively, of Figure 10 in comparison

to the transmission through a random particle mixture (Figure 10d). It is evident that some

parts of the spectrum show transmission while other ultrasound frequencies

are blocked. In general, it should be possible to realize phononic

crystals with lattice spacings ranging from 7.4 mm down to 74 μm

in the 0.1–10 MHz range of ultrasound frequencies. More complex

behavior can be expected for other crystal geometries, but the use

of standing waves will restrict the number of accessible trapping

geometries. Guevara Vasquez and Mauck141 investigated this problem theoretically for D spatial

dimensions with the limitation that N = D pairs of opposing transducers are used.141 For D = 2 they found that three of the six possible

Bravais lattice classes can be obtained by superposition of two standing

waves, and for D = 3 they found 6 out of 14 possible

classes. In two dimensions the available crystal geometries are orthorhombic

centered, hexagonal, and tetragonal. In three dimensions the triclinic

primitive, orthorhombic face-centered, trigonal primitive, cubic primitive,

cubic face-centered, and cubic body-centered can be generated. More

complex arrangements are to be expected if the number of transducer

pairs exceeds the available dimensions N > D, but this has not yet been shown to date.

and az = λz/2. The properties of

the phononic crystal can thus be changed in a dynamic and reconfigurable

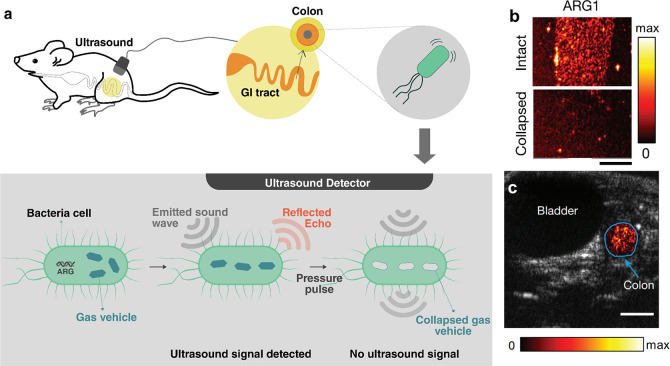

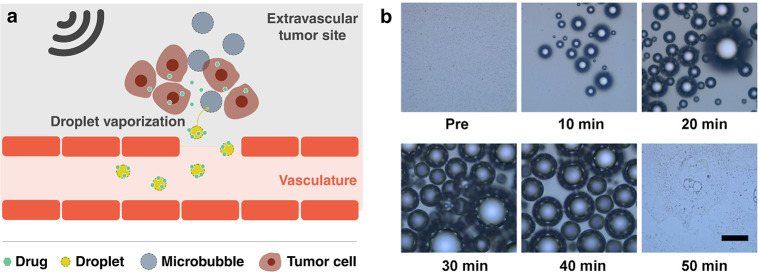

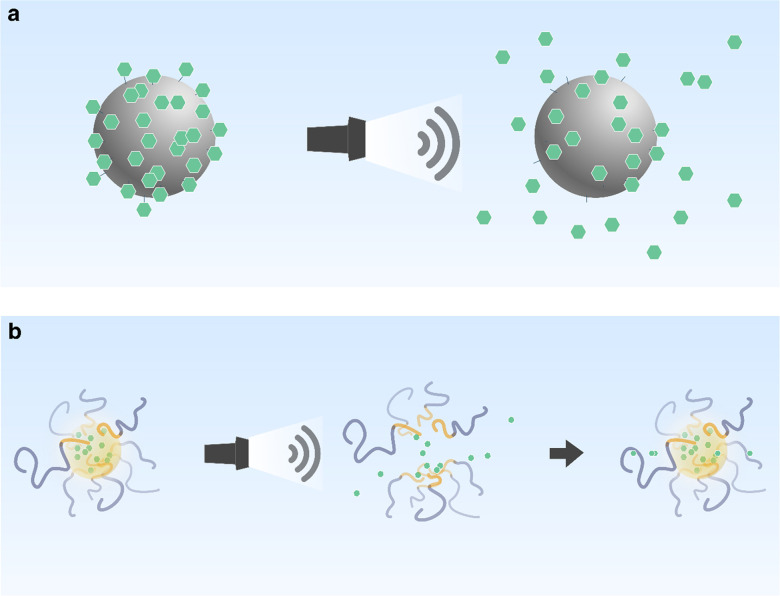

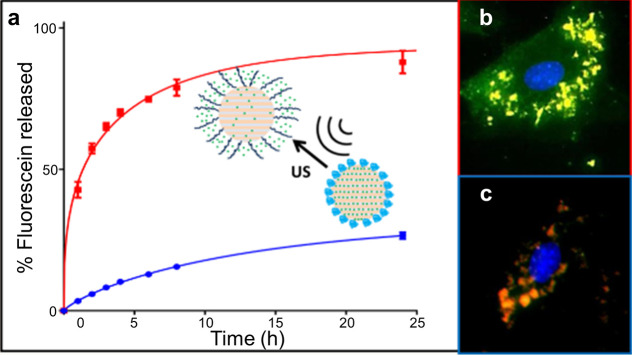

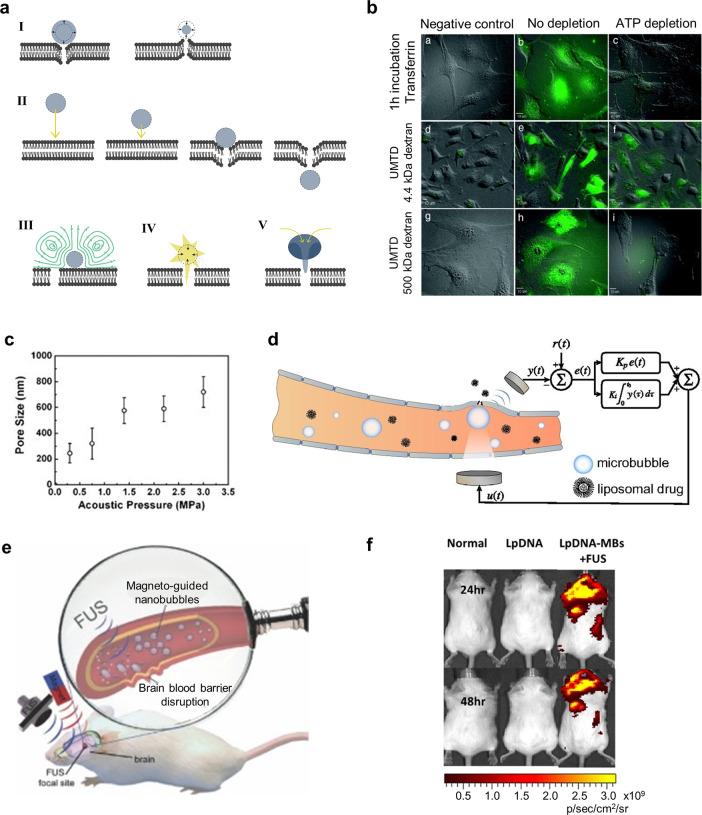

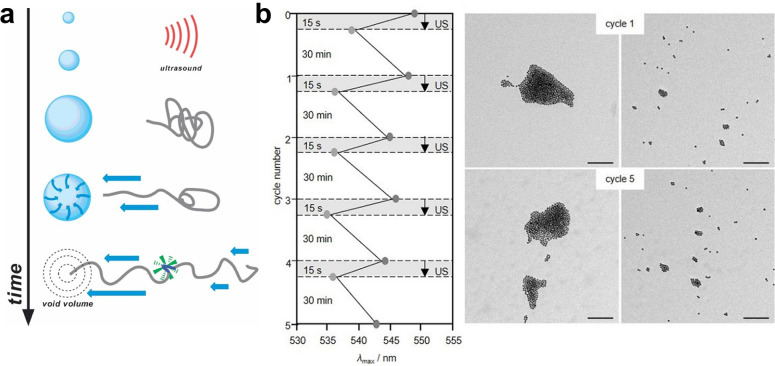

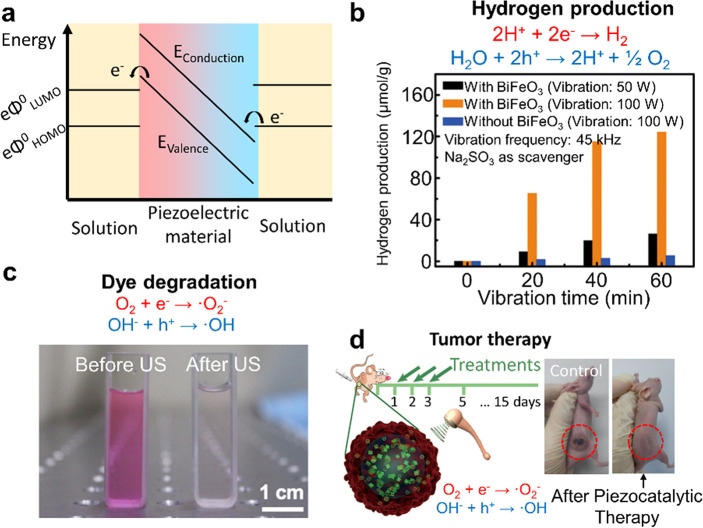

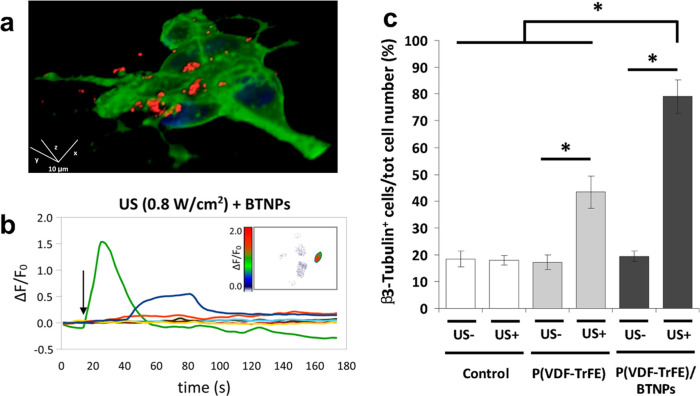

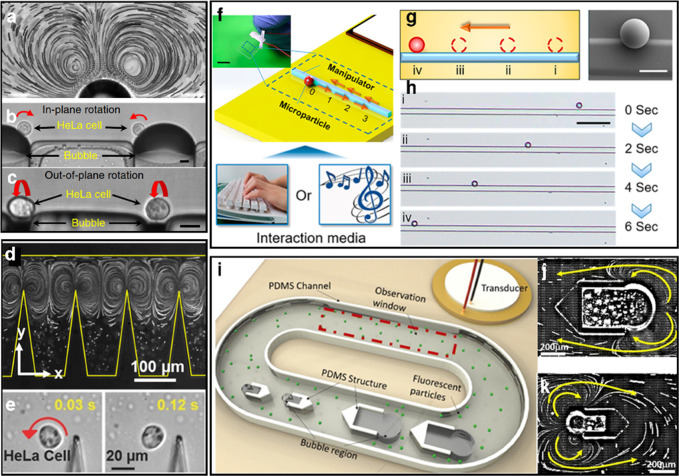

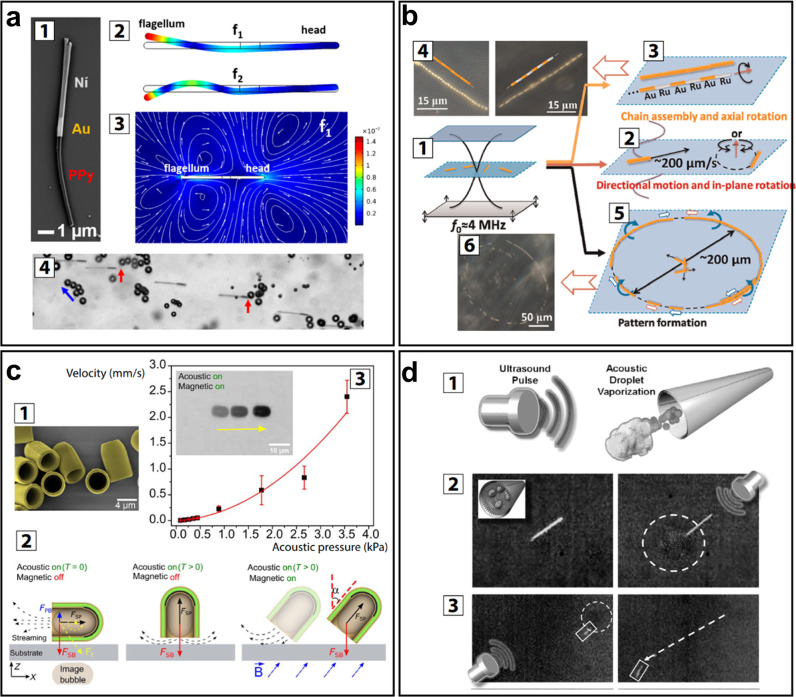

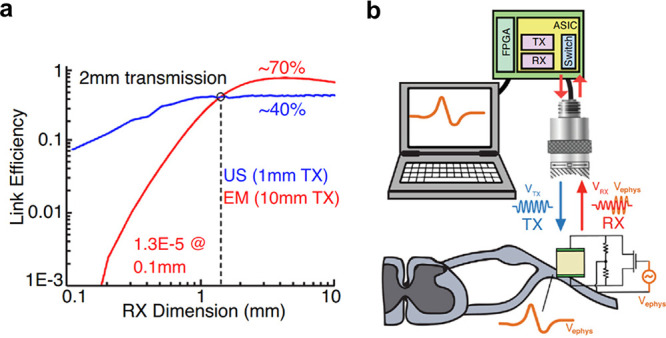

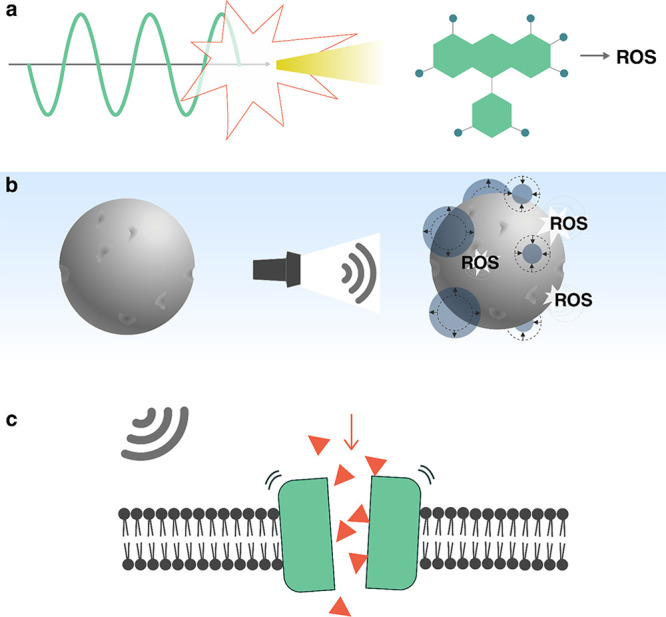

way. In this example, band gaps appeared in the acoustic transmission