Abstract

Introduction

Burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units (ICUs) is a serious issue that leads to early retirement and medication errors. Their gender, lower years of experience, and lower education have been reported as risk factors. Simultaneously, mutual support—commonly referred to as “back-up behavior,” in which staff members support each other—is critical for team performance. However, little is known about the influence of mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals on burnout. The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality refers to mutual support as the involvement of team members in: assisting one another, providing and receiving feedback, and exerting assertive and advocacy behaviors when patient safety is threatened.

Objective

This study aimed to verify the hypothesis that lower mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals is associated with increased probability of burnout.

Methods

A web-based survey was conducted from March 4 to 20, 2021. All ICU healthcare professionals in Japan were included. An invitation was sent via the mailing list of the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine and asked to mail to local communities and social network services. We measured burnout severity using the Maslach Burnout-Human Services Survey and mutual support using the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire, as well as occupational background. The cutoff value for burnout was predefined and conducted logistic regression.

Results

We received 335 responses, all of which were analyzed. The majority of respondents were nurses (58.5%), followed by physicians (18.5%) and clinical engineers (10.1%). The burnout group scored significantly lower on mutual support than the non-burnout group. After adjusting for covariates in a logistic regression, low mutual support was an independent factor predicting a high probability of burnout.

Conclusions

This study suggests that it is important to focus on mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals to reduce the frequency of burnout.

Keywords: burnout, healthcare professionals, intensive care unit, mutual support, COVID-19

Introduction

Burnout in healthcare professionals is associated with depression, suicidal ideation, early retirement, and medication errors (Menon et al., 2020; Moss et al., 2016; Nantsupawat et al., 2016). The prevalence of burnout among intensive care unit (ICU) physicians and nurses was estimated at approximately 30% to 45%, and burnout occurs at higher rates than in non-ICU staff (Embriaco et al., 2007a, 2007b; Moss et al., 2016; Ramírez-Elvira et al., 2021). Age, gender, educational history, years of experience, and insufficient experience have been reported as risk factors for burnout among ICU healthcare professionals (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2017; Merlani et al., 2011; See et al., 2018).

Mutual support is defined as providing feedback and coaching to improve performance or, when a lapse is detected, assisting teammates in performing a task, and completing a task for the team member when they are overloaded (Baker et al., 2010). Furthermore, the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality referred to mutual support as the involvement of team members in: 1) assisting one another, 2) providing and receiving feedback, and 3) exerting assertive and advocacy behaviors when patient safety is threatened (TeamSTEPPS® Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) Manual, n.d.). Therefore, we hypothesized that low mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals is associated with a higher frequency of burnout.

Review of Literature

In recent years, burnout has been one of the most widely discussed mental health issues in our society. The concept of burnout was first described by Freudenberger (1974). He described the state of burnout in the workplace as “becoming exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources” (Freudenberger, 1974). The processual features of burnout indicate the cumulative negative consequences of long-term work-related stress and fatigue (Golonka et al., 2017). Burnout reportedly produces physical symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, frequent headaches and gastrointestinal problems, insomnia, and shortness of breath, as well as psychological symptoms such as frustration, anger, and depression (Heinemann & Heinemann, 2017). Burnout in health care workers is most commonly diagnosed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) developed by Maslach (Maslach et al., 1997). The MBI-HSS consists of three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and feelings of reduced personal accomplishment. Emotional exhaustion refers to a feeling of being overwhelmed. Depersonalization means feelings of impersonalization that seem unrealistic and not one's own. Lack of personal accomplishment leads to reduced self-achievement at work (Maslach et al., 1997). Several studies have used the MBI-HSS to measure burnout across various disciplines, and it has become an occupational phenomenon and a mental health issue (Chirico, 2017). In 2019, WHO included burnout in the revised International Classification of Diseases-11 (Atroszko et al., 2020).

A previous study of nurses indicated that relationships with head nurses or physicians were significant risk factors for burnout (Poncet et al., 2007). This implies that relationship factors such as communication and work environment in the healthcare profession may be important in the development of burnout. Previous studies indicate that low mutual support is associated with patient safety and high medical staff turnover (Hai-Ping et al., 2020). Therefore, we hypothesized that low mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals is associated with a higher frequency of burnout. Mutual support may be important in burnout because low mutual support indicates poor interpersonal relationships and lack of communication among ICU healthcare professionals.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the association between mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals and burnout. In this study, we examined the association between burnout and mutual support using a cross-sectional survey of ICU healthcare professionals.

Methods

Design and Settings

An online web-based cross-sectional study was conducted for all ICU healthcare professionals in Japan from March 4 to March 20, 2021, using SurveyMonkey (SVMK Inc., San Metro, USA). Survey Monkey is a platform that maintains a high level of security (https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/data-security-and-compliance/). We sent invitations via the mailing list of the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine and asked them to mail invitations to ICU healthcare professionals in the local community and social network services.

Sample

Participants in this study were all healthcare professionals working in Japanese ICUs.

Survey Components

The survey comprised four components. The first was a questionnaire regarding individual and institutional characteristics. We defined a housemate as a person living with the participant. In addition to physicians, nurses, and therapists, we included clinical engineers (CEs) in the participants. CEs are recipients of a national qualification and are responsible for the maintenance of various medical equipment and the operation of ventilators, blood purification therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as per the physician's recommendation. The second part included the working environment, such as shift type, number of night shifts, hours worked per week, and ICU type. We categorized the shifts into three categories as follows. Only day shift, double shift (the 24-h work period was divided into two shifts: day and night shifts, which were worked in shifts), triple shift (the 24-h work period was divided into three shifts: day, evening, and night shifts, which were worked in shifts). We categorized ICU types into four categories based on a past report (Pronovost et al., 2002). These included: 1) open ICU (no critical care physician), 2) semi open ICU (the intensivist is involved in the care of the patient only when the attending physician requests a consultation), 3) semi closed ICU (the intensivist is not the patient's primary attending physician, but every patient admitted to the ICU receives a critical care consultation), and 4) closed ICU (the intensivist is the patient's primary attending physician). Furthermore, we included frequency of involvement in caring for COVID-19 patients because the COVID-19 pandemic may have increased burnout among healthcare professionals (Miller et al., 2021). The third component consisted of the 23-item Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) (Maslach et al., 1997), which was used to assess burnout among healthcare professionals. The fourth component consisted of a 7-item subscale of the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) (TeamSTEPPS® Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) Manual, n.d.) to assess mutual support.

Instruments

The MBI-HSS is widely used to assess burnout and consists of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA). This Japanese-translated instrument has been validated (Higashiguchi et al., 1998). The alpha value for each factor in the reliability of the Japanese version of the MBI-HSS was 0.92, 0.91, and 0.88, respectively. Each question has a 7-point Likert score (0 = “never” and 6 = “frequent”). The cut-off value for burnout syndrome was defined as emotional exhaustion (EE) ≥27 and/or depersonalization (DP) ≥10. The cut-off scores used in this study were based on a 2016 systematic review, which identified the most widely used criteria for defining burnout (Doulougeri et al., 2016).

The T-TPQ was developed by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. For each item on the T-TPQ subscale, respondents rated their level of agreement on a standard 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, slightly disagree, neutral, slightly agree, strongly agree). A Japanese version of the T-TPQ has been shown to have good validity and reliability (Unoki et al., 2021). Higher mutual support subscale scores indicate higher mutual support among healthcare providers.

Bias

Due to our methodology, selection bias was not avoided; however, our objectives were not to clarify prevalence, but to examine relationships between mutual support and burnout among healthcare professionals working in the ICU. Thus, selection bias did not significantly contribute to our findings. However, some confounding factors existed, such as the years of work experience (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2017) and type of healthcare professional (Merlani et al., 2011) that possibly influenced teamwork perception and burnout. Therefore, we controlled for these factors using multivariable statistics.

Sample Size

We estimated a 30% prevalence of burnout (Teixeira et al., 2013), and 10 covariates were to be adjusted for the logistic regression analysis. Thus, we estimated a minimum sample size of 330 participants (Peduzzi et al., 1996).

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed data were represented as mean ± standard deviation; otherwise, we used the median and interquartile range (IQR). First, we conducted descriptive statistics. Second, the respondents’ demographic characteristics, mutual support, and working environment were compared among those with or without burnout using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Third, we performed logistic regression analysis adjusted for covariates to identify the association between burnout and mutual support from previous studies and clinical perspectives. Covariates were predefined based on previous studies and clinical perspectives. The covariates were as follows: years of work experience (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2017; See et al., 2018), sex (Merlani et al., 2011), type of healthcare professional (Merlani et al., 2011), experience of caring for COVID-19 patients (Azoulay et al., 2020), housemate status (Duarte et al., 2020), and number of hours worked per week (Embriaco et al., 2007b). The results of the multivariable analysis are shown with odds ratios [ORs], 95% confidence intervals [CIs], and p-values. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and R 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethical Considerations

The protocol for this research project was approved by a suitably constituted Research Ethics Committee [hidden for anonymized peer review] of the affiliated university hospital, and it conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval No. 2-1-55). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents. Participants read the study procedure and purpose online and participated through free will. As per the recommendation of the IRB, consent was implied if respondents checked the box on the first page of the web-based form indicating that they understood what the research entailed and agreed to participate.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Three hundred and thirty-five participants responded. All responses were included in the analyses. In this study, we recruited participants through the mailing lists and social network services, thus response rates could not be calculated. The survey respondents’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Respondents.

| Variables | Overall n = 335 |

Physicians n = 62 |

Nurses n = 196 |

CE n = 34 |

Others n = 43 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (men), n (%) | 180 (53.7) | 48 (77.4) | 63 (32.1) | 33 (97.1) | 36 (83.7) |

| Age category (years), n (%) | |||||

| 20–29 | 32 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 25 (12.8) | 3 (8.8) | 4 (9.3) |

| 30–39 | 135 (40.3) | 19 (30.6) | 82 (41.8) | 11 (32.3) | 23 (53.5) |

| 40–49 | 131 (39.1) | 30 (48.4) | 72 (36.7) | 16 (47.1) | 13 (30.2) |

| 50–59 | 28 (8.4) | 6 (9.7) | 15 (7.7) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (7.0) |

| > 60 | 9 (2.7) | 7 (11.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | 227 (67.8) | 60 (96.8) | 96 (49.0) | 32 (94.1) | 39 (90.7) |

| Housemates’ status, n (%) | 258 (77.0) | 62 (100.0) | 121 (61.7) | 34 (100.0) | 41 (95.4) |

| Dependent status, n (%) | 178 (53.1) | 48 (77.4) | 70 (35.7) | 30 (88.2) | 30 (69.8) |

| Position, n (%) | |||||

| Manager, n (%) | 126 (37.6) | 22 (35.5) | 65 (33.2) | 21 (61.8) | 18 (41.9) |

| Number of beds in hospital, n (%) | |||||

| < 200 | 10 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 9 (4.6) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| 201–300 | 27 (8.1) | 3 (4.8) | 19 (9.7) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (7.0) |

| 301–500 | 174 (51.9) | 34 (54.8) | 101 (51.5) | 18 (52.9) | 21 (48.8) |

| 501–1000 | 87 (26.0) | 19 (30.7) | 47 (24.0) | 6 (17.7) | 15 (34.9) |

| >1001 | 37 (11.0) | 6 (9.7) | 20 (10.2) | 7 (20.6) | 4 (9.3) |

| Type of hospital, n (%) | |||||

| University, n (%) | 135 (40.3) | 29 (46.8) | 73 (37.2) | 15 (44.1) | 18 (41.9) |

| Type of ICU, n. (%) | |||||

| Open ICU | 82 (24.5) | 1 (1.6) | 65 (33.2) | 6 (17.6) | 10 (23.3) |

| Semi-open ICU | 82 (24.5) | 19 (30.6) | 42 (21.4) | 11 (32.4) | 10 (23.3) |

| Semi-closed ICU | 110 (32.8) | 29 (46.8) | 52 (26.5) | 12 (35.3) | 17 (39.5) |

| Closed ICU | 61 (18.2) | 13 (21.0) | 37 (18.9) | 5 (14.7) | 6 (13.9) |

| Number of beds in ICU (median [IQR]) | 10 [6,14] | 10 [6,14] | 8 [6,13] | 12 [8,12] | 9 [6,8.5] |

| Years of experience (median [IQR]) | 15 [10,21] | 16 [12.3,23] | 15 [10,20] | 15.5 [11,21.8] | 13 [10,12,5] |

| Shift, n (%) | |||||

| Only day shift | 83 (24.8) | 21 (33.9) | 14 (7.1) | 7 (20.6) | 41 (95.4) |

| Double shift | 188 (56.1) | 39 (62.9) | 120 (61.2) | 27 (79.4) | 2 (4.6) |

| Triple shifts | 64 (19.1) | 2 (3.2) | 62 (31.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Involved in COVID-19 patient management, n (%) | 303 (90.5) | 61 (98.4) | 174 (88.8) | 33 (97.1) | 35 (81.4) |

CE = Clinical Engineers; ICU = Intensive care unit; IQR = Interquartile Range.

A majority of respondents were nurses (58.5%), followed by physicians (18.5%). Approximately half of respondents (53.7%) were men, and most of them had more than 10 years of ICU experience (80.9%). Approximately 85% of respondents were involved in COVID-19 patient management (85.4%).

Associations of Work and Personal Environments and Mutual Support with Burnout

Table 2 shows the comparison of the characteristics and mutual support scores between respondents with or without burnout.

Table 2.

Associations of Work and Personal Environments and Mutual Support with Burnout.

| Variables | Overall n = 335 |

Burnout | 95%CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n = 148 |

No n = 187 |

||||

| Gender (men), n. (%) | 180 (53.7) | 69 (38.3) | 111 (61.7) | .021 | |

| Age category (years), n. (%) | |||||

| 20–29 | 32 (9.6) | 15 (46.9) | 17 (53.1) | 1.000 | |

| 30–39 | 135 (40.3) | 63 (46.7) | 72 (53.3) | .501 | |

| 40–49 | 131 (39.1) | 56 (42.7) | 75 (57.3) | .735 | |

| 50–59 | 28 (8.4) | 10 (35.7) | 18 (64.3) | .428 | |

| > 60 | 9 (2.7) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | .308 | |

| Marital status, n. (%) | 227 (67.8) | 89 (39.2) | 138 (60.8) | .01 | |

| Housemates’ status, n. (%) | 258 (77.0) | 106 (41.1) | 152 (58.9) | .049 | |

| Dependent status, n. (%) | 178 (53.1) | 68 (38.2) | 110 (61.8) | .021 | |

| Type of healthcare professions, n. (%) | |||||

| Physicians | 62 (18.5) | 22 (35.5) | 40 (64.5) | .156 | |

| Nurses | 196 (58.5) | 96 (49.0) | 100 (51.0) | .044 | |

| CE | 34 (10.1) | 16 (47.1) | 18 (52.9) | .720 | |

| Others (Physical therapist, Occupational therapist, pharmacist, Nursing assistant) | 43 (12.8) | 14 (32.6) | 29 (67.4) | .138 | |

| Position, n. (%) | |||||

| Manager | 126 (37.6) | 48 (38.1) | 78 (61.9) | .089 | |

| Night shift, n. (%) | 252 (75.2) | 119 (47.2) | 133 (52.8) | .056 | |

| Type of hospital (university), n. (%) | 135 (40.3) | 55 (40.7) | 80 (59.3) | .341 | |

| Open ICU, n. (%) | 83 (24.8) | 44 (53.0) | 39 (47.0) | .074 | |

| Involved in COVID-19 patient management, n. (%) | 303 (90.4) | 137 (45.2) | 166 (54.8) | .266 | |

| Number of ICU beds (median [IQR]) | 9[6,12] | 10[6,16] | 1–1.71–1.73 | .994 | |

| Number of hours worked per week (median [IQR]) | 44[40,52] | 45[40,50] | −3.06–3.18 | .972 | |

| Years of experience (median [IQR]) | 14[10,3] | 15[11,21.5] | 0.41–3.77 | .015 | |

| Mutual support (median [IQR]) | 24[21,26] | 25[24,27] | 0.97–2.54 | <.001 | |

IQR = interquartile range; CE = Clinical Engineer; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ICU = Intensive care unit.

In the univariable analysis, men had a significantly lower probability of burnout than women (p = .021). Respondents with housemates had a significantly lower probability of burnout. (p = .049). Nurses had a significantly higher frequency of burnout than other healthcare professionals (p = .044). Mutual support scores were significantly lower in respondents with burnout than those without it. The results of the subgroup analysis comparing burnout among healthcare professionals is shown in Appendix 1.

Influence of Mutual Support on Burnout among Healthcare Professionals

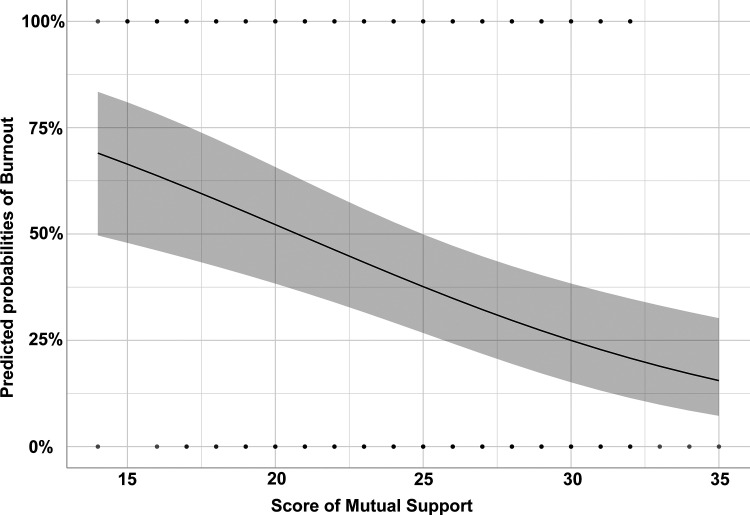

The results of the logistic regression analysis adjusted for pre-defined covariates to examine the hypothesis are shown in Table 3. Low mutual support was an independent factor associated with the frequency of high severity of burnout (OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.839–0.948, p < .001). The relationships between mutual support scores and the probability of burnout after adjusting for pre-defined covariates are shown in Figure 1. There was no statistically significant association between burnout and involvement in COVID-19 patient management.

Table 3.

Risk Factors of Frequency of Burnout in Multivariable Analysis.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (men) | 1.57 | 0.938–2.62 | .086 |

| Years of experience | 0.97 | 0.941–0.998 | .039 |

| Physicians | 0.85 | 0.356–2.049 | .724 |

| Nurses | 0.75 | 0.354–1.577 | .445 |

| Clinical Engineers | 0.51 | 0.197–1.318 | .165 |

| Mutual support | 0.89 | 0.839–0.948 | <.001 |

| Involved in COVID-19 patient management | 1.54 | 0.837–2.815 | .166 |

| Housemates’ status | 0.63 | 0.358–1.112 | .111 |

| Number of hours worked per week | 1.00 | 0.986–1.02 | .718 |

OR = odds ratio; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Figure 1.

The association between mutual support score and probabilities of burnout. The association between mutual support scores and the probability of burnout after adjusting for pre-defined covariates. Gray area indicates 95% confidential interval.

Discussion

In this study, higher mutual support was related to lower probability of burnout among ICU healthcare professionals. To our knowledge, no previous study of multi-professionals in ICUs has investigated the association between mutual support and frequency of burnout. There are several possible explanations for lower mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals being associated with a higher probability of burnout.

First, it is likely that reduced mutual support depends on ICU healthcare professionals’ interpersonal relationships. It has been reported that lack of interpersonal relationships affects multi-professional collaboration and is associated with mental health disorders among ICU healthcare professionals (Ntantana et al., 2017). Additionally, it has been reported that the conflictual structure of healthcare professions causes lack of communication, exposure to verbal abuse, assertiveness, and burnout (Alameddine et al., 2015; Salazar et al., 2014). A culture of mutual support is both an individual and an organizational issue. Organizations with good teamwork have been reported to have positive clinical outcomes. Strong multi-professional collaboration improves patient outcomes (Harvey & Davidson, 2016). Furthermore, organizations with better mutual support reported lower staff retirement intentions (Bruyneel et al., 2017). Therefore, preventing burnout among ICU healthcare professionals includes enhancing their mutual support system.

In this study, the type of healthcare profession was irrelevant to the probability of burnout. Previous studies have shown that physicians and nurses are at a higher risk of burnout (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2017; Pastores et al., 2019). The difference between our findings and previous research may be explained by differences in duties performed and organizational culture as defined by each country's healthcare system. Additionally, we included CE who are uncommon outside Japan. This may have contributed to our findings.

In this study, there was no relationship between experience in dealing with COVID-19 patients and burnout. Previous review reported that the prevalence of burnout is 3.1 ∼ 43.0% in healthcare professionals involved in caring for COVID-19 patients (Chirico et al., 2021). Thus, caring for COVID-19 patients would be expected to be associated with a higher probability of burnout. It was reported that spirituality as a psychological skill to be increased through workplace health promotion was important in dealing with COVID-19 related burnout (Chirico, 2021). We did not identify why caring for COVID-19 patients was not a risk factor for burnout in this study. The survey period may be one possible explanation as it was conducted approximately one year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A similar result was reported in Japan in November to December 2020. Specifically, nurses’ involvement in caring for COVID-19 was not an independent factor for PTSD, anxiety, and depression (Tatsuno et al., 2021).

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study was that it was among one of the few studies that showed an association between high frequency of burnout and low mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals.

This study has several limitations. First, our findings may be influenced by selection bias because our recruitment sources included mailing lists and social network services. However, we believe that participants with high teamwork spirit and no burnout were unlikely to respond with a willing attitude toward participation. Based on the proportionate incidence of burnout in this study to the existing literature (Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2015) and the varied characteristics, we believed that our recruitment channels exerted minimal influence on our findings. Second, in this study, we did not collect data on ICU healthcare professionals’ educational history. Previous studies have shown that educational history is associated with a higher frequency of burnout (See et al., 2018). Adjusting for educational history may alter the association between high frequency of burnout and low mutual support. Therefore, educational history should be considered in future studies.

Implications for Practice

Spiritual coping includes a set of religious and spiritual rituals or practices used by individuals to control and overcome stressful situations (Cabaço et al., 2018). Occupational health surveillance and promotion with spiritual coping to reduce burnout may increase the resilience of these workers (Chirico & Magnavita, 2019).

We found that lower mutual support was associated with higher burnout. TeamSTEPPS is a teamwork system for healthcare professionals that aims to improve healthcare quality, safety, and efficiency. We recommend the implementation of interventions such as team training tools to promote patient safety (Weaver et al., 2013). A systematic review on TeamSTEPPS showed that training with TeamSTEPPS improved teamwork attitudes, perceptions, and performance, and efficiency of patient care (Welsch et al., 2018). It has also been reported that the TeamSTEPPS program improves teamwork and clinical outcomes (Salas et al., 2008; Schmutz & Manser, 2013). In addition, bedside rounding has been reported to enhance communication among ICU professionals, which may enhance mutual support in the ICU (Blakeney et al., 2021). Using such a program to enhance ICU healthcare professionals’ mutual support system may prevent burnout.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that low mutual support among ICU healthcare professionals was independently associated with a high frequency of burnout. Thus, to reduce burnout among this population, it may be important to: 1) focus on mutual support, 2) introduce the TeamSTEPPS program or bedside rounding, and 3) facilitate occupational health surveillance and workplace health promotion.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608221084977 for Influence of Mutual Support on Burnout among Intensive Care Unit Healthcare Professionals by Junpei Haruna, Takeshi Unoki, Koji Ishikawa, Hideaki Okamura, Yoshinobu Kamada and Naoya Hashimoto in SAGE Open Nursing

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical consideration: The protocol for this research project was approved by a suitably constituted Research Ethics Committee of Sapporo Medical University, and it conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, Approval No. 2-1-55.

Funding information: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a research grant from Hokkaido university of science (Koji Ishikawa, 2021) and Sapporo medical university (Junpei Haruna, 2021).

ORCID iDs: Junpei Haruna https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8413-502X

Takeshi Unoki https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7778-4355

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Alameddine M., Mourad Y., Dimassi H. (2015). A national study on nurses’ exposure to occupational violence in Lebanon: Prevalence, consequences and associated factors. PloS One, 10(9), e0137105. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko P. A., Demetrovics Z., Griffiths M. D. (2020). Work addiction, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, burn-out, and global burden of disease: implications from the ICD-11. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 660. 10.3390/ijerph17020660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E., De Waele J., Ferrer R., Staudinger T., Borkowska M., Povoa P., Iliopoulou K., Artigas A., Schaller S. J., Hari M. S., Pellegrini M., Darmon M., Kesecioglu J., Cecconi M. on behalf of ESICM. (2020). Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Annals of Intensive Care, 10(1), 110. 10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. P., Amodeo A. M., Krokos K. J., Slonim A., Herrera H. (2010). Assessing teamwork attitudes in healthcare: Development of the TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 19(6), e49. 10.1136/qshc.2009.036129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney E. A. R., Chu F., White A. A., Smith G. R., Jr., Woodward K., Lavallee D. C., Salas R. M. E., Beaird G., Willgerodt M. A., Dang D., Dent J. M., Tanner E. I., Summerside N., Zierler B. K., O’Brien K. D., Weiner B. J. (2021). A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–16. 10.1080/13561820.2021.1980379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyneel L., Thoelen T., Adriaenssens J., Sermeus W. (2017). Emergency room nurses’ pathway to turnover intention: A moderated serial mediation analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(4), 930–942. 10.1111/jan.13188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabaço S. R., Caldeira S., Vieira M., Rodgers B. (2018). Spiritual coping: A focus of new nursing diagnoses. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 29(3), 156–164. 10.1111/2047-3095.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F. (2017). Is burnout a syndrome or an occupational disease? Instructions for occupational physicians. Epidemiologia e Prevenzione, 41(5–6), 294–298. https://10.19191 /EP17.5-6.P294.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F. (2021). Spirituality to cope with COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and future global challenges. Journal of Health and Social Sciences, 6(2), 151–158. 10.19204/2021/sprt2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F., Ferrari G., Nucera G., Szarpak L., Crescenzo P., Ilesanmi O. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. Journal of Health and Social Sciences, 6(2), 209–220. https://doi.org/10.19204/2021/prvl7 [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F., Magnavita N. (2019). The spiritual dimension of health for more spirituality at workplace. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 23(2), 99. 10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_209_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doulougeri K., Georganta K., Montgomery A. (2016). “Diagnosing” burnout among healthcare professionals: Can we find consensus? Cogent Medicine, 3(1), 1–10. 10.1080/2331205X.2016.1237605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte I., Teixeira A., Castro L., Marina S., Ribeiro C., Jácome C., Martins V., Ribeiro-Vaz I., Pinheiro H. C., Rodrigues Silva A., Ricou M., Sousa B., Alves C., Oliveira A., Silva P., Nunes R., Serrão C. (2020). Burnout among Portuguese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1885. 10.1186/s12889-020-09980-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embriaco N., Azoulay E., Barrau K., Kentish N., Pochard F., Loundou A., Papazian L. (2007a). High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 175(7), 686–692. 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embriaco N., Papazian L., Kentish-Barnes N., Pochard F., Azoulay E. (2007b). Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 13(5), 482–488. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. The Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), 159–165. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garrouste-Orgeas M., Perrin M., Soufir L., Vesin A., Blot F., Maxime V., Beuret P., Troché G., Klouche K., Argaud L., Azoulay E., Timsit J. F. (2015). The iatroref study: Medical errors are associated with symptoms of depression in ICU staff but not burnout or safety culture. Intensive Care Medicine, 41(2), 273–284. 10.1007/s00134-014-3601-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Urquiza J. L., Vargas C., De la Fuente E. I., Fernández-Castillo R., Cañadas-De la Fuente G. A. (2017). Age as a risk factor for burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: A meta-analytic study. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(2), 99–110. 10.1002/nur.21774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golonka K., Mojsa-Kaja J., Gawlowska M., Popiel K. (2017). Cognitive impairments in occupational burnout–error processing and its indices of reactive and proactive control. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(676), 1–13. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai-Ping Y., Wei-Ying Z., You-Qing P., Yun-Ying H., Chi C., Yang-Yang L., Li-Li H. (2020). Emergency medical staff’s perceptions on cultural value difference-based teamwork issues: A phenomenological study in China. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(1), 24–34. 10.1111/jonm.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey M. A., Davidson J. E. (2016). Postintensive care syndrome: right care, right now…and later. Critical Care Medicine, 44(2), 381–385. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann L. V., Heinemann T. (2017). Burnout research: emergence and scientific investigation of a contested diagnosis. SAGE Open, 7(1), 2158244017697154. 10.1177/2158244017697154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiguchi K., Morikawa Y., Miura K., Nishijo M., Tabata M., Yoshita K., Sagara T., Nakagawa H. (1998). [The development of the Japanese version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the examination of the factor structure]. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. Japanese Journal of Hygiene, 53(2), 447–455. 10.1265/jjh.53.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S. E., Leiter M. (1997). Maslach Burnout Inventory. In: Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources, 3rd Edition, Scarecrow Education, Lanham, 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Menon N. K., Shanafelt T. D., Sinsky C. A., Linzer M., Carlasare L., Brady K. J., Stillman M. J., Trockel M. T. (2020). Association of physician burnout with suicidal ideation and medical errors. JAMA Network Open, 3(12), e2028780–e2028780. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlani P., Verdon M., Businger A., Domenighetti G., Pargger H., Ricou B., & STRESI + Group. (2011). Burnout in ICU caregivers: A multicenter study of factors associated to centers. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 184(10), 1140–1146. 10.1164/rccm.201101-0068OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. G., Roberts K. J., Smith B. J., Burr K. L., Hinkson C. R., Hoerr C. A., Rehder K. J., Strickland S. L. (2021). prevalence of burnout among respiratory therapists amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Respiratory Care, 66(11), 1639–1648. 10.4187/respcare.09283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss M., Good V. S., Gozal D., Kleinpell R., Sessler C. N. (2016). An official critical care societies collaborative statement-burnout syndrome in critical care health-care professionals: A call for action. Chest, 150(1), 17–26. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantsupawat A., Nantsupawat R., Kunaviktikul W., Turale S., Poghosyan L. (2016). Nurse burnout, nurse-reported quality of care, and patient outcomes in Thai hospitals. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48(1), 83–90. 10.1111/jnu.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntantana A., Matamis D., Savvidou S., Giannakou M., Gouva M., Nakos G., Koulouras V. (2017). Burnout and job satisfaction of intensive care personnel and the relationship with personality and religious traits: An observational, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 41, 11–17. 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastores S. M., Kvetan V., Coopersmith C. M., Farmer J. C., Sessler C., Christman J. W., D’Agostino R., Diaz-Gomez J., Gregg S., Khan R. A., Kapu A. N., Masur H., Mehta G., Moore J., Oropello J., Price K., & Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) Task Force of the Society of the Critical Care Medicine. (2019). Workforce, workload, and burnout among intensivists and advanced practice providers: A narrative review. Critical Care Medicine, 47(4), 550–557. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peduzzi P., Concato J., Kemper E., Holford T. R., Feinstein A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(12), 1373–1379. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncet M. C., Toullic P., Papazian L., Kentish-Barnes N., Timsit J.-F., Pochard F., Chevret S., Schlemmer B., Axoulay É. (2007). Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 175(7), 698–704. 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronovost P. J., Angus D. C., Dorman T., Robinson K. A., Dremsizov T. T., Young T. L. (2002). Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: A systematic review. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(17), 2151–2162. 10.1001/jama.288.17.2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Elvira S., Romero-Béjar J. L., Suleiman-Martos N., Gómez-Urquiza J. L., Monsalve-Reyes C., Cañadas-De la Fuente G. A., Albendín-García L. (2021). Prevalence, risk factors and burnout levels in intensive care unit nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11432. 10.3390/ijerph182111432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas E., DiazGranados D., Klein C., Burke C. S., Stagl K. C., Goodwin G. F., Halpin S. M. (2008). Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors, 50(6), 903–933. 10.1518/001872008X375009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar I. C., Roldan G. M., Garrido L., Ramos-Navas Parejo J. M. (2014). Assertiveness and its relationship to emotional problems and burnout in healthcare workers. Behavioral Psychology-Psicologia Conductual, 22(3), 523–549. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293163615 [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., Manser T. (2013). Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 110(4), 529–544. 10.1093/bja/aes513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See K. C., Zhao M. Y., Nakataki E., Chittawatanarat K., Fang W.-F., Faruq M. O., Wahjuprajitno B., Arabi Y. M., Wong W. T., Divatia J. V., Palo J. E., Shrestha B. R., Nafees K. M. K., Binh N. G., Al Rahma H. N., Detleuxay K., Ong V., Phua J., & SABA Study Investigators and the Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. (2018). Professional burnout among physicians and nurses in asian intensive care units: A multinational survey. Intensive Care Medicine, 44(12), 2079–2090. 10.1007/s00134-018-5432-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuno J., Unoki T., Sakuramoto H., Hamamoto M. (2021). Effects of social support on mental health for critical care nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan: A web-based cross-sectional study. Acute Medicine & Surgery, 8(1), e645. 10.1002/ams2.645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TeamSTEPPS® Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) Manual. (n.d.). https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/reference/teamperceptionsmanual.html

- Teixeira C., Ribeiro O., Fonseca A. M., Carvalho A. S. (2013). Burnout in intensive care units - a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: A descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiology, 13(1), 38. 10.1186/1471-2253-13-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki T., Matsuishi Y., Tsujimoto T., Yotsumoto R., Yamada T., Komatsu Y., Kashiwakura D., Yamamoto N. (2021). Translation, reliability and validity of Japanese version the TeamSTEPPS® teamwork perceptions questionnaire. Nursing Open, 8(1), 115–122. 10.1002/nop2.609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver S. J., Lubomksi L. H., Wilson R. F., Pfoh E. R., Martinez K. A., Dy S. M. (2013). Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(5 Pt 2), 369–374. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch L. A., Hoch J., Poston R. D., Parodi V. A., Akpinar-Elci M. (2018). Interprofessional education involving didactic TeamSTEPPS® and interactive healthcare simulation: A systematic review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(6), 657–665. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1472069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-son-10.1177_23779608221084977 for Influence of Mutual Support on Burnout among Intensive Care Unit Healthcare Professionals by Junpei Haruna, Takeshi Unoki, Koji Ishikawa, Hideaki Okamura, Yoshinobu Kamada and Naoya Hashimoto in SAGE Open Nursing