Abstract

The Chinese traditional medicine mao-bushi-saishin-to (MBST), which has anti-inflammatory effects and has been used to treat the common cold and nasal allergy in Japan, was examined for its effects on the therapeutic activity of a new benzoxazinorifamycin, KRM-1648 (KRM), against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection in mice. In addition, we examined the effects of MBST on the anti-MAC activity of murine peritoneal macrophages (Mφs). First, MBST significantly increased the anti-MAC therapeutic activity of KRM when given to mice in combination with KRM, although MBST alone did not exhibit such effects. Second, MBST treatment of Mφs significantly enhanced the KRM-mediated killing of MAC bacteria residing in Mφs, although MBST alone did not potentiate the Mφ anti-MAC activity. MBST-treated Mφs showed decreased levels of reactive nitrogen intermediate (RNI) release, suggesting that RNIs are not decisive in the expression of the anti-MAC activity of such Mφ populations. MBST partially blocked the interleukin-10 (IL-10) production of MAC-infected Mφs without affecting their transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-producing activity. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis of the lung tissues of MAC-infected mice at weeks 4 and 8 after infection revealed a marked increase in the levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-10, and TGF-β mRNAs. KRM treatment of infected mice tended to decrease the levels of the test cytokine mRNAs, except that it increased TGF-β mRNA expression at week 4. MBST treatment did not affect the levels of any cytokine mRNAs at week 8, while it down-regulated cytokine mRNA expression at week 4. At week 8, treatment of mice with a combination of KRM and MBST caused a marked decrease in the levels of the test cytokines mRNAs, especially IL-10 and IFN-γ mRNAs, although such effects were obscure at week 4. These findings suggest that down-regulation of the expression of IL-10 and TGF-β is related to the combined therapeutic effects of KRM and MBST against MAC infection.

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infections are frequently encountered in patients with AIDS and in other types of immunocompromised hosts (35). Clinical management of MAC infections is difficult, since MAC organisms are resistant to common antituberculosis drugs such as isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and rifampin (4). Although some new drugs, including clarithromycin and rifabutin, are fairly effective in controlling MAC bacteremia in AIDS patients (4, 17), the treatment of pulmonary MAC infections is still difficult, even with the use of multidrug regimens containing these drugs (5, 17).

Recently, KRM-1648 (KRM), a new benzoxazinorifamycin with excellent anti-MAC activity, has been developed (19, 26, 31). Although one research group reported that KRM was inefficacious in controlling MAC infection induced in mice when drug treatment was initiated after the establishment of a severe infection (22), many investigations indicated that this new rifamycin derivative has potent therapeutic efficacy against MAC infections in mice and rabbits (8, 29, 31). Therefore, KRM may be useful for clinical control of intractable MAC infections in humans. Indeed, this drug is in phase I trials as a new component of multidrug regimens for the treatment of MAC infection and tuberculosis.

The Chinese medicine mao-bushi-saishin-to (MBST), which is a mixture of extracts from three medicinal herbs, mao, saishin, and hou-bushi, has long been used in Japan for treatment of the common cold (23). This drug is also efficacious in controlling perennial nasal allergy (20, 25). Indeed, it has been demonstrated to suppress experimental passive cutaneous anaphylaxis induced in rats, presumably by inhibiting histamine release from mast cells (27, 28). In Japan, MAC patients receiving KRM might use MBST for treatment of respiratory infections and nasal allergy. Thus, it is important to assess drug-to-drug interaction between KRM and MBST, which may be induced in vivo when both drugs are concomitantly administered to MAC patients. In the present study, we have examined the effects of MBST on the therapeutic effect of KRM against MAC infection induced in mice. We found that MBST did not interfere with but moderately increased the therapeutic efficacy of KRM by potentiating KRM-mediated killing and inhibition of MAC organisms residing in host macrophages (Mφs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

MAC N-444 (serovar 8), which we previously isolated from patients with MAC infection and identified as M. avium by DNA probe testing, was cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment and 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 80, and a bacterial suspension prepared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin was frozen at −80°C until use. The MAC organisms yielded smooth, transparent, and flat colonies on Middlebrook 7H11 (Difco) agar plates, a characteristic of virulent colonial variants of MAC.

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Japan Clea Co., Osaka, Japan. When BALB/c mice were intravenously (i.v.) infected with 3.8 × 106 CFU of M. avium N-444, progressive bacterial growth was observed at sites of infection, resulting in very heavy bacterial loads in the visceral organs at 1 year after infection: 9.2 and 8.6 log U in the lungs and spleen, respectively.

Special agents.

MBST was obtained from Kotaro Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan. For preparation of MBST, a mixture of three medicinal herbs including Mao, Saishin, and Hou-Bushi was extracted with hot water (100°C) for 1 h, filtered, and then lyophilized. MBST prepared from the same batch was used throughout the experiments. MBST powder was initially dissolved in PBS and subsequently diluted with RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (BioWhittaker Co., Walkersville, Md.) before use in in vitro experiments. MBST contains a number of pharmacologically active components, including mao-derived l-ephedrine and ephedran; saishin-derived methyleugenol, elemicin, l-asarinin, and hygenamine; and hou-bushi-derived aconitine, coryneine, and mesaconitine. KRM was obtained from Kaneka Corporation, Hyogo, Japan, and finely emulsified in 2.5% gum arabic–0.2% Tween 80 before use in in vivo experiments.

Experimental infection.

Six-week-old BALB/c mice infected i.v. with 107 CFU of MAC N-444 were given no drug or KRM finely emulsified in 0.1 ml of 2.5% gum arabic–0.2% Tween 80 and/or MBST dissolved in saline by gavage once daily five times per week from day 1 after infection for up to 8 weeks. Doses of KRM and MBST were fixed to be nearly equivalent to their clinical dosages by weight as follows: KRM, 20 mg/kg; MBST, 50 or 100 mg/kg. At day 1 and week 8, mice were sacrificed and examined for bacterial loads in the lungs by counting the CFU in the homogenates of individual organs using Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates. When healthy volunteers (53- to 80-kg body weights) were orally administered 400 mg of MBST containing 5 mg of l-ephedrine, the maximum drug concentration in serum and the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h of l-ephedrine in the blood were estimated to be 19.5 ± 0.7 ng/ml and 192 ± 9 ng · h/ml, respectively (21). Similar pharmacokinetics of l-ephedrine has been reported for mice orally administered a crude aqueous extract of ephedra (mao, one of the major components of MBST) (16).

Intracellular growth of MAC in Mφs.

Mφ monolayer cultures prepared by seeding 3 × 105 zymosan A (1 mg)-induced peritoneal exudate cells of 10- to 12-week-old BALB/c mice in 6.0-mm-diameter culture wells (96-well flat-bottom plate; Becton Dickinson & Company, Lincoln Park, N.J.) were incubated in 0.2 ml of 5% FBS–RPMI medium with or without the addition of MBST at concentrations of 1 to 100 μg/ml at 37°C for 2 days in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2–95% humidified air). After washing with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% FBS, the Mφs were incubated in 0.1 ml of the medium containing 1.5 × 106 CFU of MAC N-444 per ml at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 2 h. The MAC-infected Mφs were then washed with 2% FBS–HBSS to remove extracellular organisms and thereafter cultivated in 0.2 ml of 5% FBS–RPMI medium in the presence (KRM, 1 μg/ml; MBST, 1 to 100 μg/ml) or the absence of each test drug for up to 7 days. At intervals, the Mφs were lysed by 10 min of treatment with 0.07% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and the cell lysate (0.28 ml) was mixed with 0.12 ml of PBS containing 20% bovine serum albumin to neutralize the sodium dodecyl sulfate. After collection of bacterial cells from the resultant Mφ lysate by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 15 min and subsequent washing of recovered bacteria with distilled water by centrifugation, the CFU were counted on 7H11 agar plates.

Mφ production of RNI.

Mφ production of reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) was measured as described previously (1). Briefly, Mφ monolayer cultures in 16-mm-diameter culture wells (24-well flat-bottom plate; Becton Dickinson) pretreated with MBST for 2 days as described above were incubated in 0.5 ml of 5% FBS–RPMI 1640 medium containing 5 × 107 CFU of MAC N-444 per ml at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 2 h. After washing with 2% FBS–HBSS, the MAC-infected Mφs were cultivated in 5% FBS–RPMI 1640 at 37°C for 24 h. Culture supernatants of the Mφs were allowed to react with Griess reagent, and the nitrite content was quantitated by measuring the A540.

IL-10 and TGF-β production by Mφs.

The 2- or 7-day culture fluids of MAC-infected Mφs with or without the MBST treatment described above were measured for interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) concentrations as previously described (32). Briefly, Immulon 4 plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with a capture antibody (Ab) for each cytokine using a rat anti-mouse IL-10 monoclonal Ab (MAb) (Genzyme Co., Cambridge, Mass.) or a mouse anti-human TGF-β MAb (also specific to mouse TGF-β) (Genzyme). A biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-10 MAb (Pharmingen Co., San Diego, Calif.) or a chicken anti-human TGF-β Ab (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) was used as the detecting Ab. After binding of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Life Technologies Co., Gaithersburg, Md.) to biotinylated MAbs (IL-10 assay) or an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken-turkey immunoglobulin G Ab (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) to a chicken anti-human TGF-β Ab (TGF-β assay), color development was performed by using p-nitrophenyl phosphate tablets (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) as the substrate.

Expression of cytokine mRNAs.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of cytokine mRNAs in lung tissues from mice infected with MAC was performed as described by Ashman et al. (3) with slight modifications. Total RNA was isolated from lung tissues harvested at weeks 4 and 8 after infection from MAC-infected mice with or without drug treatment by using the ISOGEN kit (Nippon Gene Co., Toyama, Japan). After DNase I (GIBCO-BRL, Rockville, Md.) treatment (1 U of DNase/μg of RNA sample) at room temperature for 15 min, the resultant RNA samples were reverse transcribed to the first chain of cDNA by using random hexamer primers (GIBCO) and 200 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (GIBCO) with a standard reaction mixture (20 μl) containing 1× RT buffer (pH 8.3); 1 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (GIBCO); and 2.0 U of RNase inhibitor (GIBCO). After a 1-h reaction at 42°C and subsequent heating at 72°C for 15 min, 1-μl aliquots of the resultant cDNA were amplified specifically by PCR in a standard reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 1× PCR buffer (pH 8.3); 0.2 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 1 U of Taq polymerase (Takara Biomedicals Co., Tokyo, Japan); and 20 pmol of the sense and antisense primers for the test cytokines (synthesized by Greiner Labortechnik Co., Tokyo, Japan) as follows (sense/antisense): TNF-α, AGCCCACGTCGTAGCAAACCACCAA/ACACCCATTCCCTTCACAGAGCAAT (14); IFN-γ, GAAAGCCTAGAAAGTCTGAATAACT/ATCAGCAGCGACTCCTTTTCCGCTT (14); IL-10, TGACTGGCATGAGGATCAGCAG/ATCCTGAGGGTCTTCAGCTT (34); TGF-β1, AGCCCTGGATACCAACTATTGCTTCAGCTCCACAG/AGGGGCGGGGCGGGGCGGGGCTTCAGCTGC (24). Reactions were carried out in a DNA Thermal Cycler (ASTEC Corp., Fukuoka, Japan) for 30 cycles including denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 58°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min for each cycle. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gels.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by using Bonferroni’s multiple t test or the Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Effects of MBST on the therapeutic activity of KRM against MAC infection.

Tables 1 and 2 show the effects of MBST on the therapeutic efficacy of KRM against MAC infection in mice. The doses of KRM (20 mg/kg) and MBST (50 or 100 mg/kg) were nearly equivalent to their clinical dosages by weight. MBST at these doses caused no acute or subacute toxicity to mice and rats when given by gavage once daily for 13 weeks (data not shown). Table 1 indicates bacterial loads in the lungs and spleen at week 4 after infection. KRM displayed significant therapeutic efficacy in terms of reduction of bacterial growth in the lungs and spleens of KRM-treated mice compared to those of untreated control mice (P < 0.05). Notably, the therapeutic efficacy of KRM, in terms of MAC growth inhibition in the lungs, was moderately increased when it was given in combination with MBST (P < 0.05 in the Mann-Whitney test), although MBST alone did not exhibit a significant therapeutic effect against MAC infection.

TABLE 1.

Therapeutic effects of KRM, MBST, and KRM-MBST against MAC infection in mice observed at 4 weeks after infectiona

| Drug(s) | Dose(s) (mg/kg) | Mean log CFU ± SEMb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs

|

Spleen

|

||||

| Day 1 | Week 4 | Day 1 | Week 4 | ||

| None | 0 | 4.29 ± 0.08 | 5.88 ± 0.09 | 5.24 ± 0.05 | 7.48 ± 0.05 |

| KRM | 20 | NDc | 5.38 ± 0.08d | ND | 6.85 ± 0.07d |

| MBST | 100 | ND | 5.72 ± 0.07 | ND | 7.53 ± 0.10 |

| KRM + MBST | 20 + 100 | ND | 5.03 ± 0.16def | ND | 6.86 ± 0.10de |

Mice infected i.v. with MAC N-444 (107 CFU) were given or not given the indicated agents by gavage either once weekly (KRM) or once daily five times per week (MBST) from day 1 for up to 4 weeks.

There were six mice per regimen.

ND, not determined.

Significantly smaller than the value of untreated control mice (P < 0.05 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

Significantly smaller than the value of mice given MBST alone (P < 0.05 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

The difference from the values of mice given KRM alone was statistically significant (P < 0.05) when assessed by the Mann-Whitney test.

TABLE 2.

Therapeutic effects of KRM, MBST, and KRM-MBST against MAC infection in mice observed at 8 weeks after infectiona

| Drug(s) | Dose(s) (mg/kg) | Mean log CFU ± SEMb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs

|

Spleen

|

||||

| Day 1 | Week 8 | Day 1 | Week 8 | ||

| None | 0 | 4.12 ± 0.07 | 7.03 ± 0.12 | 5.00 ± 0.14 | 7.93 ± 0.11 |

| KRM | 20 | NDc | 5.20 ± 0.06d | ND | 7.12 ± 0.07d |

| MBST | 50 | ND | 7.02 ± 0.11 | ND | 7.85 ± 0.08 |

| KRM + MBST | 20 + 50 | ND | 4.79 ± 0.09def | ND | 6.89 ± 0.08de |

Mice infected i.v. with MAC N-444 (107 CFU) were given or not given the indicated agents by gavage either once weekly (KRM) or once daily five times per week (MBST) from day 1 for up to 8 weeks.

There were five mice per regimen.

ND, not determined.

Significantly smaller than the value of untreated control mice (P < 0.01 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

Significantly smaller than the value of mice given MBST alone (P < 0.01 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

The difference from the values of mice given KRM alone was almost significant (P < 0.07) in Bonferroni’s multiple t test. Moreover, this difference was assessed as statistically significant by the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05).

Table 2 shows the bacterial loads in the viscera at week 8 after infection. Also at this phase of infection, KRM treatment significantly reduced the growth of MAC in the lungs and spleen (P < 0.01), while MBST exerted no such effect. A moderate increase in the therapeutic efficacy of KRM was also achieved by the combination of KRM with MBST (P < 0.05 and P < 0.07 by the Mann-Whitney test and Bonferroni’s test, respectively). These findings may indicate that MBST is capable of potentiating the in vivo therapeutic effects of KRM against MAC infection. However, we cannot conclude that MBST is also efficacious in controlling human MAC diseases in combination with KRM, since the pharmacokinetic profiles of KRM and MBST in humans are not strictly the same as those in mice.

Effects of MBST on Mφ anti-MAC activity.

It is of interest to study the immunological mechanisms of the increase in the therapeutic efficacy of KRM due to combined administration with MBST. In the next series of experiments, we investigated the effects of MBST on some Mφ functions related to their antimicrobial activity, since Mφs are known to play crucial roles in the expression of host resistance to mycobacterial infections (9).

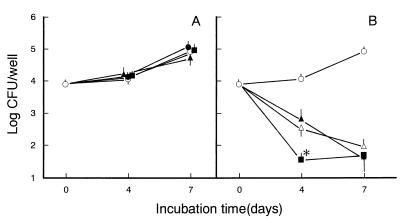

First, the effects of MBST on the mode of intracellular growth of MAC in murine peritoneal Mφs were examined. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment of Mφs with MBST alone at 1 to 100 μg/ml did not significantly affect the growth of the microorganisms. MBST at these concentrations exhibited no cytotoxic effect against Mφs in terms of cell morphology and dye-excluding ability and had no bacteriostatic effect against MAC organisms (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment of Mφs with 100-μg/ml MBST significantly promoted KRM-mediated killing of MAC organisms residing in Mφs during a 4-day cultivation of infected Mφs (P < 0.05). In a separate experiment, a similar combined effect was also noted for a combination of KRM and MBST in the killing of intra-Mφ MAC during a 4-day cultivation (unpublished observation). These findings may indicate that MBST is capable of potentiating Mφ anti-MAC activity, although its efficacy is not so potent.

FIG. 1.

Effects of MBST on Mφ anti-MAC activity. Mφs were preincubated in culture medium in the absence or presence of 1-, 10-, or 100-μg/ml MBST for 2 days, infected with MAC for 2 h, and further cultured in the same medium with or without the addition of MBST at corresponding doses (1, 10, or 100 μg/ml, respectively), in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 1-μg/ml KRM, for up to 7 days. Symbols in panel A: ○, without MBST treatment; ●, ▴, ■, treated with 1-, 10-, or 100-μg/ml MBST, respectively. Symbols in panel B: ○, no drug added; ▵, KRM alone; ▴, ■, treatment with KRM plus MBST at 10 and 100 μg/ml, respectively. Each symbol indicates the mean ± the standard error of the mean (n = 3). The asterisk indicates a value significantly smaller than that of Mφs treated with KRM alone (P < 0.05 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

Second, we examined the effects of MBST on Mφ production of RNI, which play roles in the expression of Mφ antimycobacterial activity (1, 9). As shown in Table 3, MBST treatment significantly reduced the accumulation of NO2− (a breakdown product of RNI) in culture fluids of MAC-infected Mφs. This may indicate an MBST-mediated increase in RNI production by Mφs, although the possibility cannot be excluded that MBST merely reduced the rate of RNI conversion to NO2−.

TABLE 3.

Effect of MBST on RNI production by MAC-infected Mφsa

| Drug used for pretreatment of Mφs (dose [μg/ml]) | MAC infection | Mean NO2− accumulation ± SEM (nanomoles/well)b | % Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | − | 6.02 ± 0.14 | |

| None | + | 11.5 ± 1.55 | |

| MBST (3) | + | 8.87 ± 0.41 | 23 |

| MBST (10) | + | 6.57 ± 0.55c | 43 |

| MBST (30) | + | 5.30 ± 0.48d | 54 |

| MBST (100) | + | 5.14 ± 0.42d | 55 |

Mφ monolayer cultures in 16-mm wells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of MBST for 2 days, infected with MAC organisms (2.5 × 107 CFU) for 2 h, and further incubated in fresh medium without test drugs for 24 h to measure subsequent production of NO2− as described in Materials and Methods.

There were three tests per treatment.

Significant inhibition (P < 0.05) by Bonferroni’s multiple t test.

Significant inhibition (P < 0.01) by Bonferroni’s multiple t test.

Effects of MBST on IL-10 and TGF-β production by Mφs.

In the next experiment, we examined the effect of MBST on Mφ production of IL-10 and TGF-β, immunoregulatory cytokines which down-regulate Mφ anti-MAC activity (6, 7, 10). As shown in Table 4, treatment of Mφs with MBST at doses of 10 to 100 μg/ml caused partial reductions in the accumulation of IL-10 in culture fluids by MAC-infected Mφs in the early phase of cultivation (day 2). The transiently increased level of IL-10 was thereafter decreased to undetectable levels by day 7 (data not shown). In the same experiment, the accumulation of TGF-β by MAC-infected Mφs was below the limit of detection in the early phase (day 2), followed by low-level accumulation in the middle phase (day 7) of Mφ cultivation (data not shown). In this case, MBST treatment caused no significant change in Mφ TGF-β production as follows: MBST (100 μg/ml)-treated Mφs, 0.29 ng/ml; untreated Mφs, 0.33 ng/ml.

TABLE 4.

Effect of MBST on IL-10 production by MAC-infected Mφsa

| Treatment of Mφs with MBST | MBST concn (μg/ml) | Cultivation time (days) | MAC infection | Mean IL-10 accumulation ± SEM (ng/ml)b | % Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | 2 | − | 2.0 ± 0.2 | ||

| − | 2 | + | 12.2 ± 0.2 | ||

| + | 10 | 2 | + | 9.5 ± 0.1c | 24 |

| + | 30 | 2 | + | 7.5 ± 0.3c | 40 |

| + | 100 | 2 | + | 7.1 ± 0.2c | 43 |

Pretreatment of Mφs with MBST, subsequent infection with MAC, and chase cultivation (2 days) of MAC-infected Mφs were performed as described in Table 3.

The values are for groups of five. The IL-10 detection limit was 0.1 ng/ml.

Significantly different from the value of control Mφs (P < 0.01 by Bonferroni’s multiple t test).

Expression of RNA messages of cytokines in the lungs of MAC-infected mice with or without drug treatment.

Profiles of the expression of the mRNAs of proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and the immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β in the lung tissues of MAC-infected mice given KRM, MBST, or both were determined by using RT-PCR analysis. Figures 2 and 3 show representative results for the lungs of six mice separately subjected to RT-PCR assay.

FIG. 2.

Effects of MBST on the expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-10, and TGF-β mRNAs in the lungs of MAC-infected mice at week 4 after infection. Induction of MAC infection and subsequent drug treatment of infected mice were as described in Table 1. RT-PCR analysis of the lungs of mice was done at week 4. The relative intensities of the RT-PCR bands of individual cytokines were calculated by normalizing to the intensity of the β-actin band. The values in parentheses are cytokine band/β-actin band ratios (the mean of six mice). The standard error of the mean ranged from 5 to 28% (TNF-α), from 14 to 29% (IFN-γ), from 11 to 28% (IL-10), and from 3 to 10% (TGF-β).

FIG. 3.

Effects of MBST on the expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-10, and TGF-β mRNAs in the lungs of MAC-infected mice at week 8 after infection. Induction of MAC infection and subsequent drug treatment of infected mice were as described in Table 2. The other details are the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 2, except that mice were sacrificed at week 8.

First, at week 4 after infection, the following profiles were observed (Fig. 2). MAC infection induced a marked increase in the levels of all test cytokine mRNAs (P < 0.01 for TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 by Bonferroni’s test), although significant expression of TGF-β mRNA was constitutively observed, even in uninfected mice, and the increase in the IL-10 mRNA level was modest. At this stage of infection, either KRM or MBST displayed marked modulating effects on the expression of the mRNAs of all of the test cytokines except IFN-γ. When MAC-infected mice were given KRM, TNF-α mRNA expression was significantly decreased (P < 0.01), while a modest decrease in IFN-γ and IL-10 mRNA levels was observed and a nearly significant (P < 0.1) increase in TGF-β mRNA was seen. MBST treatment caused a significant reduction in TNF-α and IL-10 mRNA levels (P < 0.05) and a moderate decrease in IFN-γ and TGF-β mRNAs. The TNF-α, IL-10, and TGF-β mRNA levels in mice given a combination of KRM and MBST were nearly the same as those in mice given MBST alone.

Second, at week 8 after infection (Fig. 3), the lungs of MAC-infected mice also showed significantly increased expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 (P < 0.05), as observed for mice examined at week 4. In this case, TGF-β mRNA was also increased but this increase was insignificant. KRM treatment of infected mice reduced these cytokine mRNA levels particularly those of TNF-α and IL-10 mRNAs, but such decreases were not significant (P < 0.25 to P < 0.5). MBST treatment did not affect the test cytokine mRNA levels, although a moderate decrease in TGF-β mRNA was observed (P < 0.25). Notably, combined use of MBST and KRM markedly reduced the levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNAs, almost abolished IL-10 mRNA expression, and moderately decreased the TGF-β mRNA level compared with those of MAC-infected mice without drug treatment or those given each drug alone. The P values of the observed decrease in the levels of these cytokine mRNAs (mice treated with KRM plus MBST versus mice given no drug) were as follows: TNF-α, P < 0.05; IFN-γ, P < 0.05; IL-10, P < 0.05; TGF-β, P < 0.005. A significant combined effect of the KRM-plus-MBST combination was observed for TNF-α and TGF-β mRNA expression (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study has revealed that the Chinese medicine MBST is capable of moderately potentiating the therapeutic efficacy of KRM against MAC infection (Tables 1 and 2). This effect of MBST appears to be related to its ability to modulate Mφ anti-MAC activity, since Mφ treatment with MBST potentiated the microbicidal activity of KRM against intra-Mφ MAC. As indicated in Table 3, MBST reduced the RNI-producing ability of MAC-infected Mφs. In preliminary experiments, Mφ production of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) was also down-regulated due to MBST treatment. Therefore, it may be thought that MBST-treated Mφs preferentially use microbicidal effectors other than RNI and ROI. This concept is consistent with our previous findings that the degree of resistance of various MAC strains to RNI and ROI did not correlate with their virulence in mice (30), indicating that RNI and ROI alone are not decisive in the host defense against MAC. Collaboration among RNI, ROI, and other Mφ antimicrobial effector molecules, such as free fatty acids and bactericidal peptides (1, 9, 18), may be required for expression of the anti-MAC activity of MBST-treated Mφs.

As shown in Table 4, MBST treatment suppressed IL-10 production by MAC-infected Mφs. Since IL-10 is an immunoregulatory cytokine with Mφ-deactivating activity and is capable of down-regulating Mφ anti-MAC activity (7, 10, 11), MBST-mediated potentiation of KRM activity against MAC residing in Mφs was due in part to reduction of Mφ IL-10 production by the action of MBST. On the other hand, MBST did not affect Mφ TGF-β production. This finding has some importance in relation to MBST administration in patients with MAC infection, since it excludes the possibility that MBST promotes the progression of MAC infection by enhancing Mφ production of TGF-β, a Mφ-deactivating cytokine which down-regulates the anti-MAC activity of Mφs (6).

RT-PCR analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in the lung tissues of MAC-infected mice with or without drug administration revealed the following. MAC infection elevated the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 mRNAs at weeks 4 and 8, while such an effect on TGF-β mRNA was obscure. Similar profiles have also been reported for TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 by other investigators (2, 12, 15). KRM treatment tended to decrease the levels of all of the test cytokine mRNAs except TGF-β mRNA at week 4. This is consistent with our previous finding that KRM administration reduced the expression of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 protein levels in the lungs and spleens of MAC-infected mice at weeks 4 and 8 (32). In this context, it has been recently reported that a potent anti-MAC drug, clarithromycin, reduced IFN-γ mRNA expression in spleen cells of MAC-infected mice at week 4 postinfection (13). In addition, the reduction of IL-10 mRNA levels in MBST-treated mice at this stage may be due to MBST-mediated down-regulation of the IL-10-producing ability of host Mφs, as evidenced in Table 3.

While MBST treatment caused a reduction in the levels of all of the test cytokine mRNAs at week 4 after infection, such effects of MBST became obscure at week 8. Moreover, the profiles of cytokine mRNA expression in mice given the KRM-plus-MBST combination differed somewhat, depending on the stage of infection, i.e., between week 4 and week 8. These situations may be related more or less to the fact that cytokines involved in host protection are different from stage to stage of MAC infection (2). For instance, it has been reported that TNF-α and IFN-γ are involved in early protection, while IFN-γ, but not TNF-α, plays a role at later time points of infection (2).

Notably, at week 8 after infection, the combination of MBST with KRM caused a marked decrease in cytokine mRNA expression compared to that in mice given KRM alone. This is due in part to the reduction of bacterial loads in the lung tissues achieved by combination therapy of KRM with MBST. The remarkable decrease in the levels of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and IFN-γ mRNAs may be attributable to down-regulation of inflammatory reactions in host mice receiving treatment with KRM plus MBST. Such mice also showed lowered expression of IL-10 and TGF-β mRNAs, both of which down-regulate Mφ anti-MAC activity (6, 7, 10, 11, 33). This might be the reason for the potentiation of the chemotherapeutic efficacy of KRM due to combined administration with MBST, particularly at week 8 after infection.

In any case, the present finding that MBST increased the therapeutic activity of KRM against MAC infection appears to be of importance for clinical management of MAC infections using rifamycin derivatives, including KRM. This finding indicates that there may be no unfavorable drug-to-drug interaction between KRM and MBST, even if these drugs are concomitantly administered to MAC patients. That is, the therapeutic efficacies of rifamycins are not decreased when patients with MAC infection receiving KRM treatment are furthermore given MBST for other purposes, such as clinical control of the common cold and perennial nasal allergy. Further studies are currently under way in order to elucidate the effects of MBST on the T-cell functions of MAC-infected mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (07670310 and 07307004) and from the U.S.-Japan Cooperative Medical Science Program. We thank Kaneka Corporation for providing KRM-1648.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akaki T, Sato K, Shimizu T, Sano C, Kajitani H, Dekio S, Tomioka H. Effector molecules in expression of the antimicrobial activity of macrophages against Mycobacterium avium complex: the roles of reactive nitrogen intermediates, reactive oxygen intermediates, and free fatty acids. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;62:795–804. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelberg R, Castro A G, Pedrosa J, Silva R A, Orme I M, Minoprio P. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha during T-cell-independent and -dependent phases of Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3962–3971. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3962-3971.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashman R B, Bolitho E M, Fulurija A. Cytokine mRNA in brain tissue from mice that show strain-dependent differences in the severity of lesions induced by systemic infection with Candida albicans yeast. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:823–830. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson C A. Treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease: a clinician’s perspective. Res Microbiol. 1996;147:16–24. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson C A, Ellner J J. Mycobacterium avium complex infection in AIDS: advances in theory and practice. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:7–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bermudez L E. Production of transforming growth factor-β by Mycobacterium avium-infected human macrophages is associated with unresponsiveness to IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1993;150:1838–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bermudez L E, Champsi J. Infection with Mycobacterium avium induces production of interleukin-10 (IL-10), and administration of anti-IL-10 antibody is associated with enhanced resistance to infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3093–3097. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3093-3097.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bermudez L E, Kolonoski P, Young L S, Inderlied C B. Activity of KRM 1648 alone or in combination with ethambutol or clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium in beige mouse model of disseminated infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1844–1848. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan J, Kaufmann S H E. Immune mechanisms of protection. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 389–415. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis M, Ghadiarian E. IL-10 neutralization augments mouse resistance to systemic Mycobacterium avium infections. J Immunol. 1993;151:5425–5430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Waal Malefyt R, Yssel H, Roncarolo M-G, Spits H, de Vries J E. Interleukin-10. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:314–320. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90082-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doherty T M, Sher A. Defects in cell-mediated immunity affect chronic, but not innate, resistance of mice to Mycobacterium avium infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:4822–4831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doherty T M, Sher A. IL-12 promotes drug-induced clearance of Mycobacterium avium infection in mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:5428–5435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehlers S, Mielke M E A, Blankenstein T, Hahn H. Kinetic analysis of cytokine expression in the livers of naive and immune mice infected with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1992;149:3016–3022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansch H C R, Smith D A, Mielke M E A, Hahn H, Bancrott G J, Ehlers S. Mechanisms of granuloma formation in murine Mycobacterium avium infection: the contribution of CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1299–1310. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.8.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada M, Nishimura M, Kase Y. Contribution of alkaloid fraction to pharmacological effects of crude Ephedra extract. Proc Symp Wakan-Yaku. 1983;16:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heifets L. Clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium complex infections. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1996;77:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiemstra P S, Eisenhauer P B, Harwig S S L, van den Barselaar M T, van Furth R, Lehrer R I. Antimicrobial proteins of murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3038–3046. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3038-3046.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inderlied C B, Barbara-Burnham L, Wu M, Young L S, Bermudez L E M. Activities of the benzoxazinorifamycin KRM 1648 and ethambutol against Mycobacterium avium complex in vitro and in macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1838–1843. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Baba S, Takagi I, Ohya Y, Yokota A, Ito H, Inagaki M, Oyama K, Hojo G, Maruo T, Higashiuchi A, Sugiyama K, Kawai T, Moribe K, Suzuki K, Takushoku H, Itaya S, Suzuki Y. Effect of Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To on nasal allergy with nasal obstruction. Pract Otol (Tokyo) Suppl. 1994;52:107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Imamura F, Iijima Y, Anjo T, Matsuki Y, Nambara T, Yamamura H, Tokuoka Y. Gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric determination of plasma and urine levels of ephedrine isomers in human subjects given a Chinese traditional drug (Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To) Igaku Kenkyu. 1991;22:416–423. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji B, Lounis N, Truffot-Pernot C, Grosset J. How effective is KRM-1648 in treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infections in beige mice? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:437–442. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaji M, Kashiwagi I, Hayashida K, Shingu S, Ishii K. Clinical effect of Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To in patients with common cold. Jpn J Clin Exp Med. 1991;68:3437–3479. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda H, Kuwahara H, Ichiyama Y, Ohtsuki M, Kurakata S, Shiraishi A. TGF-β enhances macrophage ability to produce IL-10 in normal and tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:4926–4932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi Y, Nakai Y, Furuya H, Esaki Y, Hachikawa K, Tamura T, Uekawa M, Sugiura Y, Iguchi H, Ohono Y, Okamoto J, Kubo T, Sugiura M, Takeda M. Clinical effect of Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To in patients with obstinate nasal blockage due to perennial rhinitis. Pract Otol (Tokyo) 1992;85:1845–1853. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito H, Tomioka H, Sato K, Emori M, Yamane T, Yamashita K, Hosoe K, Hidaka T. In vitro antimycobacterial activities of newly synthesized benzoxazinorifamycins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:542–547. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.3.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibata H, Kohno S, Ohata K. Effects of Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To on experimental allergic models in mice. Jpn J Allergol. 1995;44:1234–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibata T, Sugiyama M. Inhibitory effects of Mao-Bushi-Saishin-To and its extractable components against histamine release from mast cells. J Med Pharmacol Soc Wakan-Yaku. 1989;6:288–289. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomioka H, Saito H, Sato K, Yamane T, Yamashita K, Hosoe K, Fujii K, Hidaka T. Chemotherapeutic efficacy of a newly synthesized benzoxazinorifamycin, KRM-1648, against Mycobacterium avium complex infection induced in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:387–393. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomioka H, Sato K, Sano C, Akaki T, Shimizu T, Kajitani H, Saito H. Effector molecules of the host defence mechanism against Mycobacterium avium complex: the evidence showing that reactive oxygen intermediates, reactive nitrogen intermediates, and free fatty acids each alone are not decisive in expression of macrophage antimicrobial activity against the parasites. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:248–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4511349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomioka H, Sato K, Hidaka T, Saito H. In vitro and in vivo antimycobacterial activities of KRM-1648, a new benzoxazinorifamycin. In: Pandalai S G, editor. Recent research developments in antimicrobial agents & chemotherapy. Trivandrum, India: Research Signpost; 1997. pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomioka H, Sato K, Shimizu T, Sano C, Akaki T, Saito H, Fujii K, Hidaka T. Effects of benzoxazinorifamycin KRM-1648 on cytokine production at sites of Mycobacterium avium complex infection induced in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:357–362. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahl S M. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) in inflammation: a cause and a cure. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:61–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00918135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida A, Koide Y, Uchijima M, Yoshida T O. Dissection of strain difference in acquired protective immunity against Mycobacterium bovis Calmette-Guerin bacillus (BCG) J Immunol. 1995;155:2057–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young L S. Mycobacterial infections in immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1996;9:240–245. [Google Scholar]