Abstract

Objective

Anaemia leads to poor health outcomes in older adults; however, most current research in China has focused on younger adults. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of anaemia and its associated factors in older adults in an urban district in China.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

An urbanised region, Shenzhen, China.

Participants

A total of 121 981 participants aged ≥65 years were recruited at local community health service centres in Shenzhen from January to December 2018.

Primary outcomes

The prevalence of anaemia was analysed and potential associated factors were evaluated.

Results

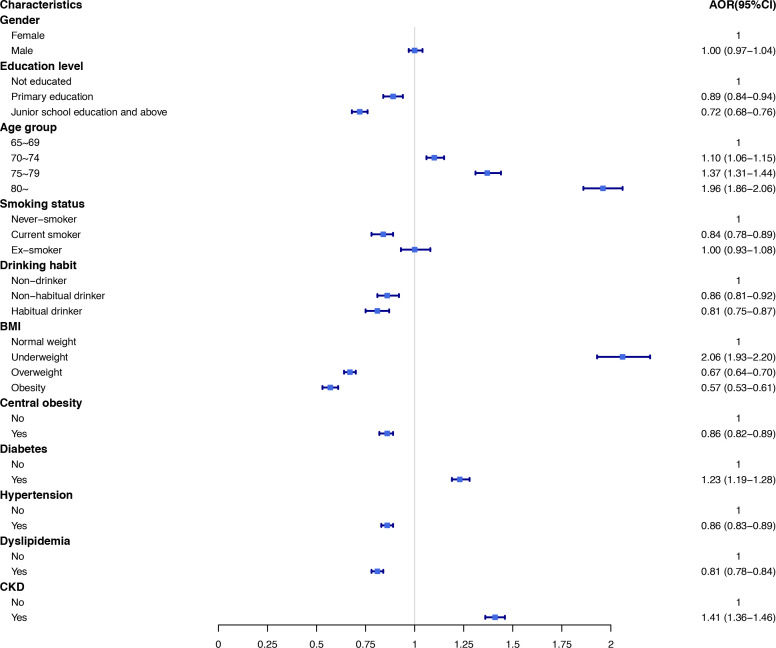

The mean haemoglobin level was 136.40±16.66 g/L and the prevalence of anaemia was 15.43%. The prevalences of mild, moderate and severe anaemia were 12.24%, 2.94% and 0.25%, respectively. Anaemia was positively associated with older age, being underweight (adjusted OR (AOR) 2.06, 95% CI 1.93 to 2.20), diabetes (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.28) and chronic kidney disease (AOR 1.41, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.46), and inversely with higher education level, current-smoker (AOR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.89), non-habitual drinker (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.92), habitual drinker (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.87), overweight (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.70), obesity (AOR 0.57, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.61), central obesity (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.89), hypertension (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.89) and dyslipidaemia (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.84).

Conclusion

Anaemia is prevalent among people aged 65 years and older in China. Screening of high-risk populations and treatment of senile anaemia should be a top priority in Shenzhen, and should be listed as important public health intervention measures for implementation.

Keywords: anaemia, epidemiology, risk management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was the first large-scale cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence of anaemia and its factors in an urban district in China.

This study had a sufficiently large sample size to detect significant differences in the prevalence of anaemia among older adults.

Convenience sampling was used to enrol the population sample.

The dataset used in this study did not provide information on the dietary behaviour of the participants.

Introduction

Anaemia results from an inadequate number of erythrocytes which leads to a decreased ability to carry oxygen to meet the body’s physiological demands. It is characterised by reduced levels of haemoglobin (Hb) in the blood in affected individuals. Anaemia may occur at all stages of life, however, older people are among the most vulnerable.1 2 Globally, 11.0% of men and 10.2% of women aged 65 years and older are anaemic.3 Anaemia is a risk factor for a variety of adverse outcomes in the older population, including hospitalisation, disability and mortality.1 Previous studies found higher mortality rates in people aged 65 years and older hospitalised for myocardial infarction, patients with systolic and diastolic chronic heart failure (CHF), and in older CHF patients with anaemia.4–6 Anaemia is also an independent risk factor for decline in physical performance and has a negative impact on quality of life, physical functioning and muscle strength in older individuals.7–9 Early identification and treatment of anaemia is therefore an important strategy to improve the quality of life of older adults with anaemia.

In China, 13.5% of the total population (approximately 190.64 million people) were aged 65 years or older in 2020,10 and increasing life expectancy and declining fertility rates mean that China is experiencing an ongoing ageing process. In line with the ageing of the population, anaemia has become an important public health problem in China. The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study showed a prevalence of anaemia in middle-aged and older Chinese residents of 12.86% from 2011 to 2012,11 and the 2010–2012 China National Nutrition and Health Survey found a prevalence of anaemia in older Chinese people of 12.6%.12 Preventing anaemia and improving the health of older adults in China are thus urgent issues. However, the only previous trial for preventing anaemia examined the use of iron-fortified soy sauce in some cities in China, which aimed to reduce the prevalence of iron-deficiency anaemia among women of reproductive age.13 The prevention of anaemia in older adults thus still presents a challenge, and limited measures have been taken to address this public health problem.

Clarifying the risk factors of anaemia in the older adults will help to identify the population at risk of anaemia, and promote the development of targeted screening and intervention measures. Economic development, living standards, body mass index (BMI), chronic disease and specific risk factors, chronic kidney disease (CKD), older age are important factors affecting anaemia.1 3 14 15 Most previous studies focused on the prevalence of anaemia among middle-aged and older adults in urban and rural districts of China, but there is a lack of large-sample studies of anaemia among older adults in urban districts.11 12 16 17 This study, therefore, aimed to examine the prevalence of anaemia and its related factors among people aged 65 or older in an urban district of China, to help develop strategies for future interventions and the prevention of anaemia in older adults living in urban districts in China.

Materials and methods

Study population

We recruited participants aged 65 years and older from the lists of all residents registered at local community health centres in Shenzhen by convenient sampling method, from January 2018 to December 2018. The staff of the local community health centres recruited older adults in their community to participate in the survey by pasting posters, placing leaflets, telephone, distributed electronic posters via Wechat. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) lived in Shenzhen for more than 6 months; (2) able to participate in the study and give informed consent; and (3) conscious and able to cooperate to complete the face-to-face interview, medical examinations and biomedical tests. Prisoners are not free to visit community health centres, and we excluded residents living in prisons. A total of 141 684 individuals were recruited in this study, accounting for 36.9% (141,684/383,700) of the resident older adult population in Shenzhen according to the 2015 population census. Data were collected at examination centres in local community health centres in the participants’ residential areas. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire, provide a fasting blood sample, and undergo physical examinations. A total of 19 703 respondents were excluded because of failure to fulfil one or all of these requirements. Finally, 121 981 participants (86.09%) were included in the final data analysis.

Questionnaire survey

Prior to the study, all investigators completed a training course to understand the methodology and process of the study. Working manuals containing questionnaire techniques, blood pressure measurement, anthropometric measurements, biological sample collection and processing information were distributed to all the investigators.

Data were recorded by face-to-face interview 1 hour after blood collection. Detailed sociodemographic characteristics and health parameters were collected by a standardised questionnaire including age, sex, education level, marital status, medical history, family health history, lifestyle behaviours and medication use. Participants were categorised according to the level of education into three categories: not educated; primary education; and junior high school education and above. Regarding drinking habits, participants were classified as habitual drinkers (drink at least once a day), non-habitual drinkers (six times a week to once a month) or non-drinker (almost never).18 Based on a previous study, we divided participants into current smokers, ex-smokers and never-smokers.19

Physical examination

Anthropometric examinations were carried out in the morning after overnight fasting by standard methods. Body height, weight and waist circumference (WC) of the participants were measured, and BMI was calculated. Blood pressure was measured twice in both arms supported at heart level with the participants in a sitting position, using a calibrated electronic sphygmomanometer and the higher level was recorded and used for statistical analysis. To obtain accurate readings, the participants were asked to rest for at least 5 min before the measurement, or if they had engaged in excessive exercise prior to the visit, to rest for at least 30 min before the measurement.

Blood sample collection and biochemical analyses

Venous blood samples were taken after overnight fasting for at least 8 hours. All blood samples were analysed in clinical laboratories at the grade 2 hospitals to which the community health centres were directly affiliated. All the laboratories had successfully completed a standardisation and competency programme. Fasting venous blood was used to measure levels of Hb, plasma glucose, creatinine, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) using an automatic biochemistry analyzer. Biochemical analysis of fresh blood samples was completed within 4 hours. Serum creatinine was used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the full age spectrum equation.20

Operational definitions/measurements

Anaemia was defined as a Hb concentration <130 g/L in men and <120 g/L in women, according to WHO standards.21 The severity of anaemia was classified as mild (110–119 g/L (women), 110–129 g/L (men)), moderate (80–109 g/L), and severe (<80 g/L).21 CKD was defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.22 A diagnosis of hypertension was considered in participants with three consecutive high readings (≥140 mm Hg systolic blood pressure (SBP) and/or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure (DBP)) with 2-week intervals or self-reported treatment with antihypertensive medication within the previous 2 weeks.23 24 Participants who met one of the following three criteria were diagnosed with diabetes: (1) previously diagnosed by professional doctors, (2) fasting plasma glucose (FBG) ≥7.0 mmol/L and (3) 2-hour plasma glucose level ≥11.1 mmol/L.25 High TC, high TG, high LDL-C and low HDL-C were diagnosed according to the 2016 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemia in Adults.26 In this study, we defined dyslipidaemia as an abnormal concentration of one or more lipid components or the use of antidyslipidaemia medications in the past 2 weeks.

Participants were divided into four groups based on the adult weight criteria published by the Ministry of Health of China (WS/T 428–2013): BMI <18.5 kg/m2 (low weight), BMI ≥18.5 kg/m2 and <24.0 kg/m2 (normal weight), BMI ≥24.0 kg/m2 and <28.0 kg/m2 (overweight) and BMI ≥28.0 kg/m2 (obesity). A WC ≥90 cm for men and ≥85 cm for women was defined as central obesity.27

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means and SD, were used to compute continuous variables. Numerical data were expressed as percentages and compared by χ2 tests. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the associations between the prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors. In the multivariate logistic regression model, the prevalence of anaemia was defined as the dependent variable, and sex, education level, age group, smoking status, drinking habit, BMI, central obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and CKD were defined as the independent variables. Data analysis was carried out using SAS V.9.4. A two-sided value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Participants and public involvement

Neither the study participants nor the public were involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study. All the participants had the option of receiving a health check and biochemical results when they visited the local community health centres.

For participants who were not educated, the participants and a proxy (family member) who accompanied the participant in the survey were informed orally (participant) and in writing (proxy) about the purpose, process, methods, benefits and health risks of the study. During the informed consent process, uneducated older adults and their proxies were able to consult the investigators with questions at any time. After explaining the concept of informed consent, uneducated older adults provided verbal agreement, and written informed consent to participate in the study was provided by their proxy. The consent processes were approved by the committee of the Center for Chronic Disease Control of Shenzhen.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The characteristics of the study participants are shown in table 1. The mean age was 71.28±5.58 years (range 65–113 years). There were 53 743 men and 68 238 women, and >50% of participants had a minimum of a junior school education. Among the study population, 8.22% were current smokers and 6.35% were habitual drinkers. The mean Hb, BMI, SBP, DBP, WC, FBG, TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C and eGFR values among all 121 981 participants were 136.40±16.66 g/L, 23.83±3.17 kg/m2, 134.71±17.69 mm Hg, 77.23±10.31 mm Hg, 85.10±8.82 cm, 5.96±1.90 mmol/L, 5.21±2.00 mmol/L, 1.57±1.14 mmol/L, 3.09±1.05 mmol/L, 1.39±0.51 mmol/L and 68.74±16.70 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. A total of 100 762 participants (82.60%) had at least one chronic disease, with hypertension (55.61%), dyslipidaemia (44.73%), CKD (31.09%) and diabetes (22.31%) being the most prevalent (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of older adults living in Shenzhen community (N=121 981)

| Characteristics | Total | 95% CI |

| Age (years) | 71.28±5.58 | 71.25 to 71.31 |

| Hb (g/L) | 136.40±16.66 | 136.30 to 136.50 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.83±3.17 | 23.81 to 23.85 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 134.71±17.69 | 134.61 to 134.81 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 77.23±10.31 | 77.18 to 77.29 |

| WC (cm) | 85.10±8.82 | 85.05 to 85.15 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.96±1.90 | 5.95 to 5.97 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.21±2.00 | 5.20 to 5.23 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.57±1.14 | 1.57 to 1.58 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 3.09±1.05 | 3.08 to 3.09 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.39±0.51 | 1.39 to 1.39 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 68.74±16.70 | 68.65 to 68.83 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 53 743 (44.06) | 43.78 to 44.34 |

| Female | 68 238 (55.94) | 55.66 to 56.22 |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| Not educated | 9888 (8.11) | 7.95 to 8.26 |

| Primary education | 43 441 (35.61) | 35.34 to 35.88 |

| Junior school education and above | 68 652 (56.28) | 56.00 to 56.56 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 10 023 (8.22) | 8.06 to 8.37 |

| Ex-smoker | 7546 (6.19) | 6.05 to 6.32 |

| Never-smoker | 104 412 (85.59) | 85.40 to 85.79 |

| Drinking habit, n (%) | ||

| Non-drinker | 101 661 (83.34) | 83.13 to 83.55 |

| Non-habitual drinker | 12 571 (10.31) | 10.14 to 10.48 |

| Habitual drinker | 7749 (6.35) | 6.22 to 6.49 |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting plasma glucose; Hb, haemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

Prevalence of anaemia in different subgroups

The overall prevalence anaemia was 15.43% and the prevalences (95% CI) of mild, moderate and severe anaemia were 12.24% (12.05% to 12.42%), 2.94% (2.84% to 3.03%) and 0.25% (0.23% to 0.28%), respectively. The prevalence of anaemia among subpopulations is shown in table 2. Anaemia was significantly more prevalent in women than in men and generally increased with age. The prevalence was lower among individuals with at least primary-level education, and lower in current smokers and habitual drinkers compared with their counterparts. The prevalence of anaemia was higher in participants with low weight and lower in those with overweight, obesity, central obesity, hypertension or dyslipidaemia. Individuals with diabetes or CKD had a higher prevalence of anaemia than those without these conditions.

Table 2.

Prevalence of anaemia in older adults living in Shenzhen community, according to sociodemographic and other characteristics

| Characteristics | Total | No of anaemia | Prevalence of anaemia (%) | 95% CI | χ2 value | P value |

| Total | 121 981 | 18 820 | 15.43 | 15.23 to 15.63 | ||

| Sex | 22.36 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 53 743 | 7946 | 14.79 | 14.49 to 15.09 | ||

| Female | 68 238 | 10 874 | 15.94 | 15.66 to 16.21 | ||

| Education level | 263.21 | <0.001 | ||||

| Not educated | 9888 | 2027 | 20.50 | 19.70 to 21.30 | ||

| Primary education | 43 441 | 7240 | 16.67 | 16.32 to 17.02 | ||

| Junior school education and above | 68 652 | 9553 | 13.92 | 13.66 to 14.17 | ||

| Age group | 1201.99 | <0.001 | ||||

| 65–69 | 60 043 | 7635 | 12.72 | 12.45 to 12.98 | ||

| 70–74 | 32 750 | 4730 | 14.44 | 14.06 to 14.82 | ||

| 75–79 | 16 599 | 3070 | 18.50 | 17.90 to 19.09 | ||

| 80– | 12 589 | 3385 | 26.89 | 26.11 to 27.66 | ||

| Smoking status | 68.89 | <0.001 | ||||

| Current smoker | 10 023 | 1253 | 12.50 | 11.85 to 13.15 | ||

| Ex-smoker | 7546 | 1047 | 13.87 | 13.09 to 14.65 | ||

| Never-smoker | 104 412 | 16 520 | 15.82 | 15.60 to 16.04 | ||

| Drinking habit | 130.24 | <0.001 | ||||

| Non-drinker | 101 661 | 16 302 | 16.04 | 15.81 to 16.26 | ||

| Non-habitual drinker | 12 571 | 1589 | 12.64 | 12.06 to 13.22 | ||

| Habitual drinker | 7749 | 929 | 11.99 | 11.27 to 12.71 | ||

| BMI | 1522.11 | <0.001 | ||||

| Low weight | 4496 | 1504 | 33.45 | 32.07 to 34.83 | ||

| Normal weight | 61 532 | 11 041 | 17.94 | 17.64 to 18.25 | ||

| Overweight | 44 644 | 5175 | 11.59 | 11.29 to 11.89 | ||

| Obesity | 11 309 | 1100 | 9.73 | 9.18 to 10.27 | ||

| Central obesity | 540.10 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 49 051 | 5897 | 12.02 | 11.73 to 12.31 | ||

| No | 72 930 | 12 923 | 17.72 | 17.44 to 18.00 | ||

| Diabetes | 27.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 27 220 | 4520 | 16.61 | 16.16 to 17.05 | ||

| No | 94 761 | 14 300 | 15.09 | 14.86 to 15.32 | ||

| Hypertension | 63.27 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 67 835 | 9883 | 14.57 | 14.30 to 14.83 | ||

| No | 54 146 | 8937 | 16.51 | 16.19 to 16.82 | ||

| Dyslipidaemia | 211.72 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 54 564 | 7354 | 13.48 | 13.19 to 13.76 | ||

| No | 67 417 | 11 466 | 17.01 | 16.72 to 17.29 | ||

| CKD | 624.34 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 37 927 | 7574 | 19.97 | 19.57 to 20.37 | ||

| No | 84 054 | 11 246 | 13.38 | 13.15 to 13.61 |

A two-sided value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Association between anaemia and related variables

Binary logistic regression analysis was carried out with presence or absence of anaemia as the dependent variable, and factors in univariate analysis as independent variables to determine the factors influencing anaemia. Primary education (adjusted OR (AOR) 0.89, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.94), junior school education and above (AOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.76) current-smoker (AOR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.89), non-habitual drinker (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.92), habitual drinker (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.87), overweight (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.70), obesity (AOR 0.57, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.61), central obesity (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.89), hypertension (AOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.89) and dyslipidaemia (AOR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.84) were independently associated with lower odds for the presence of anaemia (figure 1), while age 70–74 years (AOR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.15), age 75–79 years (AOR 1.37, 95% CI 1.31 to 1.44), age ≥80 years (AOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.86 to 2.06), underweight (AOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.93 to 2.20), diabetes (AOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.28) and CKD (AOR 1.41, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.46) were independently associated with greater odds (figure 1). However, there was no significant difference in the risk of anaemia in relation to sex.

Figure 1.

Risk factor analyses of the prevalence of anaemia in older adults living in Shenzhen community. AOR, adjusted OR; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

This was the first large-scale cross-sectional survey to report the prevalence of anaemia in older adults (aged 65 years or older) living in an urban district of China. This study demonstrated that the prevalence of anaemia was relatively high, representing a public health problem in Shenzhen. After controlling for the confounding factors, we found that the prevalence of anaemia varied with education level, age group, smoking status, drinking habit, BMI, central obesity and some non-communicable diseases. The prevalence of anaemia among older adults in an urban district in China in the current study was 15.43%, which was higher than the 12.86% reported in previous national studies in China,11 but lower than the 18.90% reported in the 2009 national survey in China.13 The difference in prevalence rates among these studies may have been caused by differences in study design, sample size, and/or the age of the study participants.

The current study found a significant negative correlation between anaemia prevalence and educational level. This was consistent with studies conducted in Nepal and Pakistan, which confirmed that a low educational level was a risk factor for anaemia.28 This relationship probably occurs because higher levels of education enable people to earn more and thus escape from the poverty trap. Multivariate analysis also identified older age as an independent risk factor for anaemia, consistent with the findings of other related studies.3 29 The prevalence of anaemia increased with age, with a 2–3 fold increase (26.89% vs 12.72%) in people aged >80 years, suggesting the need for routine screening for anaemia in this high-risk subgroup.

Current smokers had a lower risk of anaemia than never smokers. Similarly, previous researches revealed that smoking was decrease the risk of anaemia.15 30 Hisa K et al found that women aged 35–49 years who were current smokers had a 25% lower risk of anaemia compared with non-smokers, after adjusting for the covariates.30 Elevated Hb levels in smokers were associated with elevated carboxyhaemoglobin (HbCO), a stable compound of Hb and carbon monoxide (CO), due to exposure to excess CO as a result of smoking.31 The form of HbCO reduces oxygen delivery, and smokers had compensatory elevated Hb to increase erythropoiesis and maintain oxygen transportation.32 This might explain why adaptation to excess CO during smoking was shown by increase in Hb and red blood cell mass.33 Habitual drinking was also associated with a decreased risk of anaemia, with a corresponding OR of 0.81, consistent with a Korean study.15 However, the direct causality of this negative correlation between alcohol drinking and anaemia is still unclear.15 Given the potential risks of alcohol and tobacco consumption to human health, we do not recommend increasing alcohol consumption or smoking to protect against anaemia.

We also found a negative association between increased BMI and anaemia prevalence, in accord with other studies conducted in China, the USA, Nepal and Pakistan.28 34 The reasons for being underweight may include poor distribution of inadequate food within the family, food insecurity, poverty and micronutrient deficiencies, which tend to coexist with other macronutrient deficiencies. The underlying mechanism accounting for the significant negative association between overweight or obesity and anaemia risk is unclear; however, there are several possible explanations. First, obese participants are less likely to be malnourished, because excess calorie intake leads to obesity,35 and overnutrition in obese participants may thus be associated with a significant reduction in anaemia risk. Second, obese participants may have a variety of other diseases that could increase Hb levels, such as obstructive sleep apnea and other obesity-related breathing disorders, which lead to chronic tissue hypoxia and increased red blood cells.36

We found that older people with diabetes had higher rates of anaemia than non-diabetics, consistent with previous studies.37 Evidence indicates that the incidence and prevalence of anaemia in patients with diabetes is often associated with erythropoietin deficiency caused by diabetic kidney damage.38 Other researchers have also shown a link between anaemia and hypertension, as shown in our current study.22

This study showed that the prevalence of anaemia was low among individuals with dyslipidaemia. A study by Zaribaf et al found a significant positive correlation between Hb levels and dyslipidaemia.39 However, this study differed from our study in that it assessed the relationship between anaemia and lipids in premenopausal women, whereas our study focused on older adults (aged 65–113 years).39 In contrast, a study conducted by other researchers in women of childbearing age found no significant association between serum LDL and anaemia.39 The reasons for the different results in terms of the relationship between dyslipidaemia and anaemia deserve further investigation. Patients with CKD have defects in renal endocrine function, resulting in decreased erythropoietin secretion by the kidney, leading to nephrogenic anaemia.40 Nearly half of all patients with CKD have anaemia.40 The current study found the similar results.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study and could only infer correlation, not causation. Second, randomised sampling would represent the best design for testing the prevalence of anaemia and its associated factors among older adults; however, large random sampling was not practically feasible and we therefore adopted a convenient sampling method to recruit older adult participants. This was a major factor preventing the extrapolation of the results to the general population. Finally, renal disease was assessed based on a one-time GFR measurement, possibly leading to overestimation of the actual prevalence of CKD. However, these limitations do not affect the significance of the results, which provide the first evidence of the prevalence and risk factors of anaemia among older adults in urban China.

Conclusion

In conclusion, anaemia is prevalent among the older adult population in China, with older age, underweight, diabetes and CKD being positively associated with anaemia, and higher education level, current-smoker, drinker, overweight, obesity, central obesity, hypertension and dyslipidaemia being negatively associated. Screening of high-risk populations, and treatment of senile anaemia should be top priorities in Shenzhen, and should be listed as important public health intervention measures for implementation.

bmjopen-2021-056100supp001.pdf (254.7KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the volunteers for their participation in the present study, and to all the investigators for their support and hard work during this survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: WN, XY and JX: study conception and design. WN, XY, YS, HZ, YZ and JX: performance of research. XY and YS data analysis and interpretation. WN and XY: writing the original draft. WN and JX: Writing the review, editing and guarantor. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. JCYJ20180703145202065),the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China(Grant No. KCXFZ20201221173600001), Shenzhen Medical Key Discipline Construction Fund, Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (Grant No. SZSM201811093), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (Grant No. A2022082).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study received ethical approval from the Center for Chronic Disease Control in Shenzhen(Grant No: SZCCC-201802, SZCCC-2020-018-01-PJ). The study complied with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the collection of data and conducting the study.

References

- 1.Working Group on "Expert Consensus on nutrition Prevention and Treatment of Iron deficiency Anemia" of Chinese Nutrition Society . Expert consensus on nutrition prevention and treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Acta Nutrimenta Sinica 2019;41:417–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e16–25. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi VE. Role of nutrition on anemia in elderly. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2016;11:e1–11. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu WC, Rathore SS, Wang Y, et al. Blood transfusion in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1230–6. 10.1056/NEJMoa010615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damman K. Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:818–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezekowitz JA MF, Armstrong PW. Anemia is common in heart failure and is associated with poor outcomes: insights from a cohort of 12065 patients with new-onset heart failure. Circulation 2003;107:223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penninx BWJH, Guralnik JM, Onder G, et al. Anemia and decline in physical performance among older persons. Am J Med 2003;115:104–10. 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00263-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penninx BWJH, Pahor M, Cesari M, et al. Anemia is associated with disability and decreased physical performance and muscle strength in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:719–24. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesari M, Penninx BWJH, Lauretani F, et al. Hemoglobin levels and skeletal muscle: results from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:M249–54. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Bureau of Statistics . Bulletin of the seventh national population census (NO. 5). Available: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202106/t20210628_1818824.html [Accessed September 26 2021].

- 11.Qin T, Yan M, Fu Z, et al. Association between anemia and cognitive decline among Chinese middle-aged and elderly: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:305. 10.1186/s12877-019-1308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang J, Wang Y. Reports of China nutrition and health survey (2010–2013). Beijing: Peking University Medical Press Co. LTD, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu X, Hall J, Byles J, et al. Dietary pattern, serum magnesium, ferritin, C-reactive protein and anaemia among older people. Clin Nutr 2017;36:444–51. 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Ye H, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of anemia and sociodemographic characteristics among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Southwest China: a longitudinal observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:535. 10.1186/s12884-020-03222-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun M-Y, Kim J-hoon, Kang J-S. Relationship between self-reported sleep duration and risk of anemia: data from the Korea National health and nutrition examination survey 2016–2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:4721. 10.3390/ijerph18094721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruan Y, Guo Y, Kowal P, et al. Association between anemia and frailty in 13,175 community-dwelling adults aged 50 years and older in China. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:327. 10.1186/s12877-019-1342-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Qin G, Liu Z, et al. Dietary balance Index-07 and the risk of anemia in middle aged and elderly people in Southwest China: a cross sectional study. Nutrients 2018;10:162. 10.3390/nu10020162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. The Lancet 2012;379:815–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Liu S, Yang L. Prevalence of smoking and knowledge about the smoking hazards among 170,000 Chinese adults: a nationally representative survey in 2013-2014. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:1644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pottel H, Hoste L, Dubourg L, et al. An estimated glomerular filtration rate equation for the full age spectrum. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:798–806. 10.1093/ndt/gfv454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85839/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed July 21 2021].

- 22.Lee Y-G, Chang Y, Kang J, et al. Risk factors for incident anemia of chronic diseases: a cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216062. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Writing Group of 2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension, Chinese Hypertension League, Chinese Society of Cardiology, Chinese Medical Doctor Association Hypertension Committee, Hypertension Branch of China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care, Hypertension Branch of Chinese Geriatric Medical Association . 2018 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiovasc Med 2019;24:24–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians and the American Academy of family physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:430–7. 10.7326/M16-1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Zhang X, Fang L, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of diabetes mellitus among middle-aged and elderly people in a rural Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joint committee for guideline revision . 2016 Chinese guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. J Geriatr Cardiol 2018;15:1–29. 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Criteria of weight for adults. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ewebeditor/uploadfile/2013/08/20130808135715967.pdf [Accessed September 26 2021].

- 28.Harding KL, Aguayo VM, Namirembe G. Determinants of anemia among women and children in Nepal and Pakistan: an analysis of recent national survey data. Matern Child Nutr 2018:e12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiseha T, Adamu A, Tesfaye M, et al. Prevalence of anemia in diabetic adult outpatients in Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One 2019;14:e0222111. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hisa K, Haruna M, Hikita N, et al. Prevalence of and factors related to anemia among Japanese adult women: secondary data analysis using health check-up database. Sci Rep 2019;9:17048. 10.1038/s41598-019-52798-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordenberg D, Yip R, Binkin NJ. The effect of cigarette smoking on hemoglobin levels and anemia screening. JAMA 1990;264:1556–9. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450120068031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma AJ, Addo OY, Mei Z. Reexamination of hemoglobin adjustments to define anemia: altitude and smoking. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2019;1450:190–203. 10.1111/nyas.14167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollini G, Maugeri U, Bernardo A, et al. Erythrocytes parameters due to aging, smoking, alcohol consumption and occupational activity in a working population of petrochemical industry. The Pavia study. G Ital Med Lav 1989;11:237–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin Y, Melse-Boonstra A, Pan X, et al. Anemia in relation to body mass index and waist circumference among Chinese women. Nutr J 2013;12. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation 2005;111:1448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz AR, Patil SP, Laffan AM, et al. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:185–92. 10.1513/pats.200708-137MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauci R, Hunter M, Bruce DG, et al. Anemia complicating type 2 diabetes: prevalence, risk factors and prognosis. J Diabetes Complications 2017;31:1169–74. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas MC. The high prevalence of anemia in diabetes is linked to functional erythropoietin deficiency. Semin Nephrol 2006;26:275–82. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaribaf F, Entezari MH, Hassanzadeh A. Association between dietary iron, iron stores, and serum lipid profile in reproductive age women. J Educ Health Promot 2014;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryu S-R, Park SK, Jung JY, et al. The prevalence and management of anemia in chronic kidney disease patients: result from the Korean cohort study for outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease (KNOW-CKD). J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:249–56. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.2.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056100supp001.pdf (254.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Not applicable.