Abstract

Objectives

This study investigates the information and policies that Canadian patient groups post on their publicly available websites about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Canadian national patient groups.

Participants

Ninety-seven patient groups with publicly available websites.

Interventions

Each patient group was contacted by email. Information from patient groups’ websites was collected about: total annual revenue for the latest fiscal year, year revenue was reported, revenue from pharmaceutical company donors, purpose of the donation, presence of donors’ logos on the website and hyperlinks to donors’ websites, previous and current employment information about board members and staff, external audits about the group’s finances and whether the group endorses products made by donors. Analysis of publicly available policies looking at: board and/or advisory board, acceptance of donations and revenue generation, independence of decision-making, endorsements, assistance to and/or interactions between patient members from a donor or another company/person acting on behalf of a donor and audits/monitoring/compliance.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Number of patient groups posting information on their websites about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies; the presence and contents of patient group policies covering different topics about relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Results

Fifty-three (54.6%) of 97 groups reported donations from pharmaceutical companies. Forty-one (42.3%) groups showed the logos of pharmaceutical companies on their websites and 22 (53.7%) had hyperlinks to pharmaceutical company websites. Twenty-five (25.8%) of these groups endorsed pharmaceutical products produced by brand-name companies that had donated to the groups. Twenty-six (26.8%) groups had policies that dealt with relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Conclusions

Pharmaceutical industry funding of the included patient groups was common. Despite this, relatively little information was provided on patient group websites about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Only 26 out of 97 groups had publicly available policies that directly dealt with their relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Keywords: health policy, medical ethics, health economics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first Canadian study to examine patient groups’ disclosure of their relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

National patient groups were identified from lists of groups registered to comment on national and provincial drug funding decisions.

A novel data extraction form was developed based on previous surveys and was pilot tested and revised based on comments from experts in the field.

Our methodology could not distinguish between groups that failed to disclose industry funding and those that received no industry funding.

Some national patient groups may not have been included because they lacked a website or were not registered to comment on drug funding decisions at the time our list was compiled.

Introduction

Patient groups serve an important function within the healthcare system for their members with a specific condition, providing information, education and support, contact with others facing the same health condition and assistance in navigating the healthcare system. Within this mandate, they often lobby Health Canada, the federal drug regulator, to approve new drugs and provincial governments for specific products to be funded for their membership.1 2

Since the Canadian federal government rolled back funding of patient groups in the mid-1990s,3 groups have sought new sources of revenue. Many patient groups receive money from pharmaceutical companies. This source of revenue has created concerns about a conflict of interest (COI) between corporate sponsors with a vested interest in supporting product sales and the patient groups and the potential for groups to adopt positions that favour their funders. Some groups have lobbied provincial governments to have their sponsors’ drugs included on provincial formularies.4 5 Patient groups are able to make submissions to the Common Drug Review and the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review, both part of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health, about whether these agencies should recommend that provincial drug plans fund medications. Between 2013 and 2018, these evaluations almost always supported funding the drug, whether the groups had a financial conflict with the company making the drug, a conflict with another company or no conflict with any company.6

In addition to the widespread concerns in health policy about pharmaceutical industry funding,7 financial transparency is an important value in the non-profit sector, which depends heavily on donations, volunteer labour and public trust.7 8 Furthermore, non-profit organisations with registered charity status are indirectly subsidised by taxpayers and thus have a public responsibility to be open about their finances.

No study has systematically investigated how transparent Canadian patient organisations that participate in drug funding assessments are about their relationships with the pharmaceutical industry and how they report financial information; for example, whether they report receiving donations from pharmaceutical companies, and whether they have policies to guide their relationships with their pharmaceutical company donors. While there are other possible approaches to retrieving information on these and related topics, notably disclosures from companies, if they exist,9–11 and interviews with patient group members,4 we focus on the information on groups’ publicly available websites. Unlike Australia and several European countries where industry self-regulation requires companies to disclose their funding to patient groups, in Canada only Ontario has passed such a law and it lies dormant under the current government.12 Websites are the most easily accessible source of information for interested parties and are the method most patient groups use to make their financial accounts available to the public.

Transparency in reporting is a first step to enabling all affected parties (patient group members, the medical community, governments, policymakers and funders) to assess the independence of groups from these funding sources and the objectivity of the information that they provide. In determining the transparency of Canadian patient groups, we adapted the survey methodology used by researchers in other jurisdictions13–18 to investigate the transparency of how patient groups report their funding links generally and in particular with pharmaceutical companies. We assessed key information about the organisation: how much financial information patient groups post on their websites—specifically, information about donations and the use of donations, the composition and employment histories of their boards and staff. Equally important, we examine whether the groups have COI policies to guide their interactions with companies.

Methods

List of patient groups

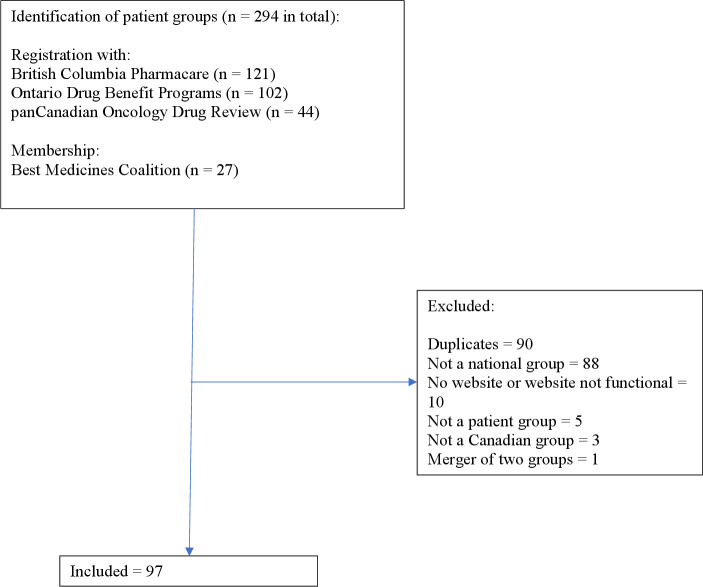

In the absence of a single national list of Canadian patient groups that advocate on drug policies, on 22–23 April 2019, we searched the websites of all provincial and territorial drug plans (online supplemental file 1) using the terms ‘registered’, ‘patient group’, ‘advocacy group’, ‘patient engagement’ and ‘patient organization’ to see if they had a list of patient groups that provided input to their decision-making processes. Only Ontario and British Columbia (BC) had such lists: BC Pharmacare registers groups that may provide public input into its drug coverage review process (121 groups)19 and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care registers advocacy groups eligible to provide patient evidence submissions on drugs listed on the drug review schedule of the Ontario Public Drug Program (102 groups).20 Additional sources for patient groups were those registered with the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (44 groups)21 and the membership of the Best Medicines Coalition, an alliance of patient advocates with a shared goal of gaining access to ‘safe and effective medicines that improve patient outcomes’ (27 groups).22 The decision to only include groups that were nationally based was made because of the limited resources available to our team.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp001.pdf (74.6KB, pdf)

We removed duplicates from our list and limited the groups to those that met the following criteria: Canadian, national in nature, self-identified as patient groups and had an active website that we could search for information.

Contacting patient groups

In addition to independently gathering information on patient groups’ websites, we contacted each patient group’s communication contact or equivalent by email in the week of 13 July 2020 to ensure that our data collection would not miss any publicly available, relevant documents that were on their websites. Online supplemental file 2 provides a generic version of the email which was modified for each individual group. The nature of the study was explained including that we were collecting only publicly available information, that while groups would be identified no individuals in those groups would be named and that all the information we collected would be placed in a publicly available website. In the email, we asked for documents on their websites that would help us determine how transparent groups are with respect to their relationship with donors: (1) the organisation’s criteria for accepting funding; (2) the organisation’s position on how funds from acceptable sources are used; (3) the organisation’s financial affiliations and donors, the sum per annum that the organisation receives from those donors; and (4) the organisation’s board membership including the names of the board members, employment information, and whether there are any current or former pharmaceutical industry employees on the board. (Revenue Canada does not require registered charitable organisations to submit audited financial statements, but organisations need to file annual reports that include basic financial information along with a list of directors. These statements do not include the names of individual donors and the amount that they donated nor any background information about the directors.) If no response was received, a reminder email was sent out after 7 weeks. Any documents received were stored in a password-protected web-based site.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp002.pdf (63.5KB, pdf)

Construction of data collection tool

We initially identified research from our personal files and those of other experts on patient group relationships with industry and COI disclosure and developed a preliminary data collection tool.13–18 This preliminary tool was then sent to five experts in the area (LB, AFB, QG, BJM, LP) and modified based on their comments. The resulting tool was then pilot tested by two authors (JL and AS) who independently abstracted information from five Australian patient groups. Results were compared and the tool was modified based on this pilot test. It was then converted into REDCap, a data management tool. The same two authors carried out a second pilot test, using five Canadian patient groups and modified the tool one final time.

Data extraction

Using the final version of our REDCap tool, between September 2020 and April 2021, we extracted the following information, if it was available, from the group’s website: total annual revenue for the latest fiscal year, year revenue was reported, revenue from pharmaceutical company donors, purpose of the donation, presence of donors’ logos on the website and hyperlinks to donors’ websites, previous and current employment information about board members and staff, external audits about the group’s finances and whether the group endorses products made by donors (online supplemental file 3).

bmjopen-2021-055287supp003.pdf (4.7MB, pdf)

We also examined websites for the presence of COI policies, codes and guidelines (collectively referred to as policies) that covered one or more of the following a priori defined content areas: board and/or advisory board, acceptance of donations and revenue generation, independence of decision-making, endorsements, assistance to and/or interactions between patient members from a donor or another company/person acting on behalf of a donor and audits/monitoring/compliance. Any policy potentially related to relationships with industry donors was collected and assessed for relevancy; only those policies covering one or more of the issues listed above were included in the analysis. If a policy was available, we recorded whether specific information was present or absent, however, we did not evaluate the strength of the policy (online supplemental file 4). To be eligible, the document had to be explicitly identified as a policy. By-laws and legal documents were excluded.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp004.pdf (8.7MB, pdf)

All four authors independently extracted information from the websites of 23–24 different patient groups and each author did a secondary review of five additional websites. Groups of two authors compared their evaluations for these five to ensure uniform extraction and then compared information in the collection tool for one out of every five of the remaining groups. Differences were resolved by consensus and if consensus could not be reached, a third author made the final decision.

Best Medicines Coalition (BMC) has a Code of Conduct Regarding Funding23 that applies to all its member groups. Consistent with our goal of examining only publicly available information, we considered the code applicable to a group if it was posted on the group’s website or if the website had a hyperlink to the code. Similarly, if groups hyperlinked to other codes or policies, such as the Canadian Consensus Framework for Ethical Collaboration,24 we also considered those codes or policies as applicable to the group. If a group indicated on its website that a code or policy was available on request, but the policy was unavailable otherwise, we did not include it.

Data analysis

We only report descriptive data in the form of the number and per cent of groups with the different types of information on their websites and with policies covering the different aspects of relationships with pharmaceutical companies. To report our results, we anonymised groups but their names, not linked to their responses, are available in online supplemental file 5.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp005.pdf (82.5KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patient groups were contacted for information about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies. There was no other patient or public involvement in this study.

Results

We initially identified 100 different groups that met our inclusion criteria and contacted all 100 by email, but during the study two groups merged and the websites of two other groups disappeared leaving a sample of 97 groups (figure 1; online supplemental file 5). Eight groups provided policies in response to our request, all of which were publicly available on their websites except one that was publicly available on request from the group (we did not request that policy as we wanted to only analyse policies that were available on websites). Fifteen groups responded but did not provide policies, 14 additional groups specifically stated that they did not want to be involved in the project and 60 groups did not reply.

Figure 1.

Selection of patient groups.

Between the material that patient groups sent us directly and those we sourced from the groups’ websites, we collected 846 pieces of material (financial statements, documents, policies, codes, reports) for analysis, with a median of 6.0 pieces per group (IQR 2.5–10.5) (online supplemental file 5).

Information on patient group websites

Fifty-three (54.6%) of 97 groups reported donations from pharmaceutical companies. The remainder may have received donations and not reported them or did not receive any donations. Only 1 (1.9%) of those 53 groups (1.0% of all 97 groups) gave the total amount—$516 000 (1.0%) out of total revenue of $54.1 million—that it received from pharmaceutical companies. None of the other groups reported the per cent of its total revenue from companies. Nine (9.3%) of the 97 groups gave dollar ranges for donations, 17 (17.5%) gave the total value of donations from all sources but none gave the exact amount of any single donation, and 8 (8.2%) broke donations down into separate categories (for example, corporate, foundations, individuals). Four (4.2%) disclosed the purpose of donations.

Fifty-one (52.6%) of 97 groups displayed the logos of their donors on the groups’ websites, including 41 (42.3%) that showed the logos of pharmaceutical companies. Thirty-one (60.8% of those displaying logos) provided a hyperlink to their donors’ websites (table 1), including 20 (48.8%) groups that had hyperlinks to pharmaceutical company websites. Sixty-seven (69.1%) groups did not endorse any products, while 30 (30.9%) endorsed specific products made by their donors, for example, by expressing approval for their funding or availability, including 25 (25.8%) groups that endorsed pharmaceutical products produced by pharmaceutical companies that had donated to the groups. Twenty-eight patient groups’ websites did not contain any of the items listed in table 1 and the median number of items was 3.0 (IQR 0.0–5.0) (online supplemental file 6).

Table 1.

Number of 97 patient groups (per cent) reporting information about revenue and donations on their websites

| Total annual revenue | Donations in general | Pharmaceutical company donations | Donor information on website | ||||||||

| Dollar range of individual donations | Total value of donations | Breakdown of total donations by source (eg, corporate, individuals) | Purpose of donations | Number of groups reporting donations | Value of donations from pharmaceutical companies | Per cent of total revenue from pharmaceutical company donations* | Donor logo | Hyperlink to donor website | |||

| 42 (43.3) | 9 (9.3) | 17 (17.5) | 8 (8.2) | 4 (4.2) | 53 (54.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | Any donor | Pharmaceutical company donor | Any donor | Pharmaceutical company donor |

| 51 (52.6) | 41 (42.3) | 31 (32.0) | 20 (20.6) | ||||||||

*Calculated from information on website.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp006.pdf (102.6KB, pdf)

Fifty-three (54.6%) groups had a brief synopsis about their board members but only six (6.2%) had detailed employment histories. Seventeen groups (17.5%) reported that board members had current or past employment with a pharmaceutical company. Four (4.1%) groups gave pharmaceutical industry employment histories about their staff (table 2). Online supplemental file 7 shows the reporting pattern by individual patient groups.

Table 2.

Number of 97 patient groups (per cent) reporting employment information about board members and staff on their websites

| Board members | Staff | |||||

| General employment history | Pharmaceutical industry employment history reported | Pharmaceutical employment history reported | ||||

| None* | Brief synopsis | Detailed† | No | Yes | No* | Yes |

| 38 (39.2) | 53 (54.6) | 6 (6.2) | 80 (82.5) | 17 (17.5) | 93 (95.9) | 4 (4.1) |

*Board members (staff) not named or no information about employment history.

†For example, year ranges with position, job title, employer.

bmjopen-2021-055287supp007.pdf (91.9KB, pdf)

No groups had external (or internal) audited reports about their activities aside from financial statements, for example, whether they followed their policies regarding industry donations or how these donations were used.

Patient group policies

Twenty-six (26.8%) groups had publicly available policies on their websites that dealt with relations with pharmaceutical companies (table 3), including 9 of the 20 members of BMC that were part of our sample. (In discussing the contents of those policies, we refer to the per cent of groups with policies and not the per cent of all groups). None of the members of BMC referred to the BMC Code on their website. Policies on seven separate topics were related to patient group–company relationships: composition and authority of the board, acceptance of donations and revenue generation, independence of decision-making, endorsements, material assistance to patient group members by a donor, other interactions between patient members of the group and a donor, and independent monitoring of activities and compliance with policies. The topic most frequently mentioned was acceptance of donations and revenue generation (16 (61.5%) of the 26 groups) and the least covered topic was independent audits of finances, monitoring of activities and compliance with policies audits (5 (19.2%) groups). The median number of topics covered per group with policies was 4 (IQR 2–6).

Table 3.

Topics related to relationships with pharmaceutical companies covered by 26 patient group policies reported on websites

| Patient group number* | Topic of policy | ||||||

| Composition and authority of board | Acceptance of donations and revenue generation | Independence of decision-making | Endorsements | Material assistance to patient group members by a donor | Other interactions between patient members of the group and a donor | Independent monitoring of activities and compliance with policies | |

| 1 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| 2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 3 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| 4 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 5 | |||||||

| 6 | |||||||

| 7 | |||||||

| 8 | x | x | x | x | |||

| 9 | x | x | x | ||||

| 10 | x | x | x | ||||

| 11 | x | x | x | ||||

| 12 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| 13 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| 14 | x | x | |||||

| 15 | x | x | x | ||||

| 16 | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| 17 | |||||||

| 18 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 19 | x | ||||||

| 20 | |||||||

| 21 | x | ||||||

| 22 | x | x | x | ||||

| 23 | x | ||||||

| 24 | x | ||||||

| 25 | x | x | x | ||||

| 26 | x | ||||||

| Total (%) | 11 (42.3) | 16 (61.5) | 13 (50.0) | 15 (57.7) | 8 (30.8) | 7 (26.9) | 5 (19.2) |

*Patient groups have been anonymised.

Table 4 provides details about how many of the 26 groups with publicly available policies regulated individual aspects of each of the seven topics referred to above. However, here we do report on all aspects of each topic. For example, ‘Composition and authority of board’ asked whether the policy covered five different aspects of the relationship, but in table 4 we only present numbers for two of these aspects. Neither of the three groups that have policies covering employment of board members required their current or previous employment to be made public on the group’s website. One group prohibited people who currently or previously worked for any donor from being on the board, while two allowed this.

Table 4.

Topics of relationships with pharmaceutical companies covered by policies on websites of 26 patient groups

| Particular topic of relationship covered by policy | Number of groups with policy mentioning topic | Policy positive about topic | Policy not positive about topic |

| Composition and authority of board | |||

| Current or previous employment of board members should be made public | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Board membership allowed for people who currently or previously worked for a donor | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Acceptance of donations and revenue generation | |||

| Source of donations should be made public | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Amount of donations should be made public | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Purpose of donations should be made public | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Donations can be tied to donor-initiated project | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Donations require approval by board or executive director | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Independence of decision-making | |||

| Group has total independence in decision-making | 13 | 13 | 0 |

| Donors allowed to directly organise seminars, lectures, projects or meetings | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Endorsements | |||

| Names of donors and/or their logos can be displayed on group’s website except to identify donor and amount of money donated | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Endorsements of products and/or companies allowed | 14 | 3 | 11 |

| Hyperlinks to donors’ websites allowed | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Patient group can directly or indirectly cooperate with companies in lobbying, testifying, addressing legislators, regulators, or policymakers, writing articles or policy briefs, etc | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Material assistance to patient group members by a donor | |||

| Donor allowed to directly pay for conference travel and accommodation for group representatives and participants | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Donor allowed to directly pay staff salary or provide staff support for group | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other interactions between patient members of group and donor | |||

| Donor allowed to provide information to patient members of group about products donor makes | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Donor allowed to access membership data or membership lists | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Donor allowed to provide patient group members with advocacy materials | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Donor allowed to provide gifts of non-educational value to patient group members | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Donor allowed to provide information to patient group members about policies or positions adopted or suggested by the donor | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent monitoring of activities and compliance with policies | |||

| Monitoring of compliance with group’s policies | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Actions if group is not compliant with its policies | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Audit of what activities donor money has been spent on | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Public availability of results of audits, monitoring, compliance | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Sixteen (61.5%) of the 26 groups had policies about all donations, but only six (23.1%) of these policies stated that the source of donations had to be made public and no group required public reporting of the amount of donations. Similarly, no group required that the purpose of donations be publicly disclosed. Five (19.2%) groups did not allow donations to be tied to a donor-initiated project and five (19.2%) groups did allow this type of donation.

Thirteen (50%) groups had policies that covered group independence and all stated that the group had total independence in decision-making. However, only two (7.7%) groups dealt with whether donors are allowed to directly organise seminars, lectures, projects or meetings (one permitted such activities, the other did not).

The policies of 14 (53.8%) groups covered endorsements and the display of donors’ names and logos. Four (15.4%) groups did allow and four (15.4%) did not allow the name and/or logo of donors to be listed on their websites except to identify the donor and the amount of money that the donor gave. Eleven (42.3%) groups did not allow endorsements of products and/or companies while three (11.5%) did. Four (15.4%) groups allowed hyperlinks to donors’ websites.

Eight (30.8%) groups had policies that regulated material assistance to patient group members by a donor and six (23.1%) groups had policies on other types of interactions between patient members of the group and donor. In the case of the former, one (3.8%) group allowed donors to directly pay for conference travel and accommodation for group representatives and participants, and two (7.7%) of the 26 groups had policies covering whether donors were allowed to directly pay staff salary or provide staff support for the group (1=yes, 1=no). In the case of the latter, two (7.7%) groups did, and two (7.7%) groups did not allow donors to provide information to patient members of the group about products the donor manufactures and two (7.7%) groups controlled whether donors were allowed to access membership data or membership lists (1=yes, 1=no).

Three (11.5%) groups mentioned that there was no monitoring of compliance with the group’s policies, while two (7.7%) groups had policies about actions that could be taken if the group was not compliant with its policies (1=action would be taken, 1=no action would be taken). Two (7.7%) groups mentioned whether there was an audit of the activities on which donor money had been spent (1=audit, 1=no audit).

Discussion

In general, we found that pharmaceutical industry funding of the included patient groups was frequent, with over half (54.6%) publicly declaring on their websites that they had received donations from companies in this sector. Despite this, relatively little information was provided on patient group websites about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Only a single group reported the total amount of revenue from this source, none gave the exact amount from individual donors and only eight groups stated the purpose of the donations. The employment history of people on patient group boards was typically not given, making it impossible to determine if they had a history of working for a pharmaceutical company. Similarly, only four groups provided employment histories of their staff.

On the other hand, some practices were common. Over 40% of the groups (41 out of 97) displayed the logos of pharmaceutical company donors on their websites including 22 groups that hyperlinked to pharmaceutical company websites. The use of logos is ambiguous and could be interpreted as transparency; alternatively, the image of logos on a site could be interpreted as promotion for the company in question, especially if a link brings a patient to the company’s web page, which might contain information about a new treatment for the patient’s condition.

Collectively, our observations can be seen as an indication that groups are not committed to being transparent about their relationships with pharmaceutical companies and/or are too closely tied to those companies.

That message about relationships is reinforced in our observation that only 26 out of 97 groups had publicly available policies on their websites that directly dealt with their relationships with pharmaceutical companies. Even when groups did have such policies, those policies often did not cover key aspects of these relationships. For example, only half of the 26 policies stated that the group had complete independence of decision-making and no group’s policy covered current or previous employment of board members. Worryingly, an even smaller minority of groups had policies that dealt with topics such as material assistance to patient group members by a donor (2 of 26 policies) and having independent monitoring of activities and compliance with policies (3 of 26 policies).

On the one hand, our results show that in the absence of publicly available policies, most groups do not make key information public about relationships with pharmaceutical companies including the purpose of donations that they received. But our findings also suggest that, in practice, some groups may follow unwritten policies. For example, although product endorsements were only dealt with in 14 policies, 67 groups did not have any product endorsements on their websites.

With some variations, our findings are broadly in line with studies from other countries that analysed information and policies on patient group websites. Ball and colleagues studied patient organisations in Australia, Canada, South Africa, the UK and the USA. Corporate donations were acknowledged in only 7 out of 37 annual reports and none of the groups gave enough information to show the proportion of their funding coming from pharmaceutical companies;13 our results found even fewer groups gave enough information (1 out of 97 groups). In another study, 36 (52.9%) out of 68 Australian groups that received industry funding disclosed the use that they made of the money,25 whereas only 4.2% did so in our study. Three out of 157 Italian patient and consumer groups (6%) reported the amount of funding from pharmaceutical companies, 25 (54%) reported the activities funded but none reported the proportion of income derived from drug companies.26 None of 24 American dermatology organisations reported the exact amount or use of donations.17 A systematic review that included five studies that examined patient groups’ websites found that a median of 75% reported receiving funding from pharmaceutical companies9 compared with 54.6% in our study. Another nine studies in the review reported that between 0% and 50% of groups disclosed the amount of funding that they received, between 0% and 6% of groups reported the proportion of their budget coming from company funding, and a median of 22% organisations reported on how the funding was used.

In the international study of patient groups by Ball and colleagues, one-third of websites showed one or more company logos and/or had links to websites of pharmaceutical companies13 compared with 22.7% (22 of 97 groups) in our study. Forty-nine out of 133 Australian groups had company logos, web links or advertisements on their websites and six had board members that were currently or previously employed by pharmaceutical companies.25 Among members of the US National Health Council,27 24 of 47 patient advocacy organisations had policies that addressed institutional COI,28 while less than one-fifth of Australian groups had publicly available policies on corporate sponsorship.25 In a systematic review, the prevalence estimates of organisational policies that govern corporate sponsorship ranged from 2% to 64%.29 In our case, 16.5% of groups had policies about donations and revenue generation.

The fact that results from multiple jurisdictions spanning the period of time from 2003 to 2021 are so similar speaks to a number of issues. First, it indicates how pervasive the relationships between patient groups and the pharmaceutical industry are. Second, it demonstrates that the lack of patient groups’ policies governing this relationship is widespread and that patient groups, wherever they are located, do not see this absence as a problem. Finally, the persistence of the results shows that challenges to the status quo have not produced any substantial movement in the behaviour of patient groups.

Limitations

As Canada has no centralised database of industry funding of patient groups, we relied on information reported on groups’ websites about their pharmaceutical industry funding and we had no way of verifying the accuracy of the information. It is difficult to know what time spans patient groups consider as relevant when disclosing funding. Some groups may disclose corporate funding in the current fiscal year; others may include only the previous year, and some may include more years. Some groups may have steady corporate income from the same sources, whereas others may only receive intermittent donations from different companies. We identified patient groups to include in our study based primarily on whether they were national and provided advice to government institutions about funding new drugs. However, this may constitute a biased sample of Canadian patient groups and other groups may differ in terms of which information is made public and the extent of their policies. We only looked at whether policies existed for certain topics and did not evaluate the strength of the policies. Other documents may have covered areas that were of interest to us, but if these documents were not identified as policies, we may have missed them. Only 37 of the 97 groups that we contacted by email responded and out of those, only 8 sent us publicly available policies. Some websites were quite complex and the location of information varied from one organisation to another; in addition, we may have missed policies on the websites of groups that did not respond or did not send us material. Some groups may have had non-publicly available policies on relevant topics and those would not have been included. Finally, we asked groups about their policies in 2019 and started collecting information from their websites in September 2020. It is possible that some groups subsequently updated their websites or policies, although we verified that the information was current to April 2021.

Conclusion

In the past few decades, patient groups in Canada have evolved rapidly to play a consequential policy role in the Common Drug Review, pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review, Quebec’s Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux, and other provincial and territorial drug programmes that decide which drugs will be included on drug formularies. By speaking from patients’ experience, groups can add to our understanding of patients’ needs and suggest useful system changes, including in drug policy. However, groups with funding from the very companies whose drugs are under review may be influenced by their industry sponsors unconsciously,30 through a complex process of corrupted knowledge systems,31 or through a transactional system of ‘asset exchange’.32 While transparency does not protect a group against such influence, openness about funding sources is a basic ethical responsibility in science, in democratic systems of governance and in non-profit organisations. Internationally, websites are the most common means of information disclosure in non-profit organisations, but they are recognised as inadequate to meet the standards of accountability the sector requires.8

Other than the law governing charitable organisations based in Canada, which makes few requirements for public reporting of corporate donations and specifically does not require organisations to declare the names of individual donors or the amount of the donations, patient groups are not answerable to any national regulatory or governing body. It is left to the groups themselves to decide what information they will reveal on their websites about corporate donations and whether they develop policies to guide their interactions with their donors. Our study found that most groups had no explicit publicly available policies guiding these interactions and that in general very limited information is disclosed.

The inconsistencies we discovered are not surprising given the absence of external requirements and the varied histories, mandates and resources of the groups themselves. Each group exists to serve its particular patient constituency, not the public at large, and the absence of requirements for public accountability is not the fault of the organisations. A few groups have taken the initiative to adopt strong transparency policies in their relations with the pharmaceutical industry and we applaud the example they set.

Patient groups have an important role to play in the healthcare system as a voice for their membership. However, they need to act, and be seen to act, as independent voices for patients. Whether this is possible while engaged in relationships with the pharmaceutical industry is a question of active debate;33 we agree with analysts who would have patient groups decrease, and ultimately end, their dependence on industry funding.34 Unfortunately, while governments in Canada actively seek to engage patient groups in their policy processes, they do not provide them with funding to support these activities.3 35 Those groups that have relationships with industry need to adopt a much more transparent approach to reporting on their relationships with these companies and to develop policies that clearly define the extent of those relationships. We recommend as a first step to achieving this goal, that groups convene a series of regional and national workshops, similar to one recently held in Australia, to develop independent guidance for groups looking for assistance in enacting sponsorship policies.36

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs Lisa Bero, Adriane Fugh-Berman, Quinn Grundy, Barbara Jane Mintzes and Lisa Parker provided comments on initial versions of the data collection tool. Drs Barbara Jane Mintzes and Lisa Parker provided feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: AS developed the idea for this study. JL and AS developed the data collection tool. JL, AS, SB and DG gathered and analysed the data. JL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AS, SB and DG revised the manuscript. JL, AS, SB and DG approved the final version of the manuscript. JL is the guarantor of this study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: In 2017–2020, JL received payments for being on a panel at the American Diabetes Association, for talks at the Toronto Reference Library, for writing a brief in an action for side effects of a drug for Michael F Smith, lawyer and a second brief on the role of promotion in generating prescriptions for Goodmans and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for presenting at a workshop on conflict of interest in clinical practice guidelines. He is currently a member of research groups that are receiving money from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. He is a member of the Foundation Board of Health Action International and the Board of Canadian Doctors for Medicare. He receives royalties from University of Toronto Press and James Lorimer & Co for books he has written. SB has received payment for commissioned briefs related to patient advocacy and industry funding from the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions and the Canadian Health Coalition. In 2018, she received royalties from UBC Press for a book on industry funding of patient groups. She is a member of the executive of the Nova Scotia Health Coalition and a member of Independent Voices for Safe and Effective Drugs. AS and DG report no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The raw data used for analysis of information on patient groups’ websites and their policies is available on request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The Human Participants Review Committee of the York University Office of Research Ethics assessed our ethics application and replied that an approval certificate was not required as this research was not subject to review.

References

- 1.Baggott R, Jones K. The voluntary sector and health policy: the role of national level health consumer and patients' organisations in the UK. Soc Sci Med 2014;123:202–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones K, Baggott R, Allsop J. Influencing the National policy process: the role of health consumer groups. Health Expect 2004;7:18–28. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00238.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batt S. Health advocacy Inc.: how pharmaceutical funding changed the breast cancer movement. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weeks C. When patients and drug makers align on a cause, whose best interests are at play? Globe and Mail 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goomansingh C. Patient groups fighting for coverage of pricey drugs get pharma funding: global news, 2014. Available: http://globalnews.ca/news/1690509/what-role-do-pharmaceutical-companies-play-in-gaining-support-for-theirdrugs/ [Accessed 31 Jul 2018].

- 6.Lexchin J. Association between commercial funding of Canadian patient groups and their views about funding of medicines: an observational study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212399. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jesus-Morales K, Prasad V. Closed financial loops: when they happen in government, they're called corruption; in medicine, they're just a Footnote. Hastings Cent Rep 2017;47:9–14. 10.1002/hast.700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega-Rodríguez C, Licerán-Gutiérrez A, Moreno-Albarracín AL. Transparency as a key element in accountability in Non-Profit organizations: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020;12:5834. 10.3390/su12145834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khabsa J, Semaan A, El-Harakeh A, et al. Financial relationships between patient and consumer representatives and the health industry: a systematic review. Health Expect 2020;23:483–95. 10.1111/hex.13013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulinari S, Martinon L, Jachiet P-A, et al. Pharmaceutical industry self-regulation and non-transparency: country and company level analysis of payments to healthcare professionals in seven European countries. Health Policy 2021;125:915–22. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rickard E, Ozieranski P, Mulinari S. Evaluating the transparency of pharmaceutical company disclosure of payments to patient organisations in the UK. Health Policy 2019;123:1244–50. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owens B. Ontario delays implementation of pharma transparency rules. CMAJ 2019;191:E241–2. 10.1503/cmaj.109-5718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ball DE, Tisocki K, Herxheimer A. Advertising and disclosure of funding on patient organisation websites: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2006;6:201. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemminki E, Toiviainen HK, Vuorenkoski L. Co-operation between patient organisations and the drug industry in Finland. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1171–5. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herxheimer A. Relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and patients' organisations. BMJ 2003;326:1208–10. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karas L, Feldman R, Bai G. Pharmaceutical industry funding to patient-advocacy organizations: a cross-national comparison of disclosure codes and regulation. Hastings International and Comparative Law Review 2019;42:453–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li DG, Singer S, Mostaghimi A. Prevalence and disclosure of potential conflicts of interest in dermatology patient advocacy organizations. JAMA Dermatol 2019;155:460–4. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCoy MS, Carniol M, Chockley K, et al. Conflicts of interest for patient-advocacy organizations. N Engl J Med 2017;376:880–5. 10.1056/NEJMsr1610625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.British Columbia . Your voice, 2021. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/health-drug-coverage/pharmacare-for-bc-residents/drug-review-process-results/your-voice#patient-group [Accessed 22 Apr 2019].

- 20.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Patient evidence submissions 2018. Available: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/patient_evidence/registered_advocacy_groups.aspx [Accessed 22 Apr 2019].

- 21.CADTH . Number of patient groups registered with CADTH’s pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review program 2018. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20210228191917/https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pcodr/Submit%20%26%20Contribute/pcodr-registered-patientadgrps.pdf [Accessed 23 Apr 2019].

- 22.Best Medicines Coalition . Coalition members, 2019. Available: https://bestmedicinescoalition.org/members/ [Accessed 23 Apr 2019].

- 23.Best Medicines Coalition . Code of conduct regarding funding for the best medicines coalition and its members, 2021. Available: https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.39/fa4.f37.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/BMC-Code-of-Conduct-Regarding-Funding.pdf [Accessed 1 May 2021].

- 24.Best Medicines Coalition, Health Charities Coalition of Canada, Canadian Medical Association . Canadian consensus framework for ethical collaboration no date. Available: http://innovativemedicines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMC_CONCENSUS_2016_HR_nobleed.pdf [Accessed 7 Jun 2021].

- 25.Lau E, Fabbri A, Mintzes B. How do health consumer organisations in Australia manage pharmaceutical industry sponsorship? A cross-sectional study. Aust Health Rev 2019;43:474–80. 10.1071/AH17288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombo C, Mosconi P, Villani W, et al. Patient organizations' funding from pharmaceutical companies: is disclosure clear, complete and accessible to the public? An Italian survey. PLoS One 2012;7:e34974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putting patients first: National Health Council, 2021. Available: https://nationalhealthcouncil.org [Accessed 30 May 2021].

- 28.Brems JH, McCoy MS. A content analysis of patient advocacy organization policies addressing institutional conflicts of interest. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10:215–21. 10.1080/23294515.2019.1670278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabbri A, Parker L, Colombo C, et al. Industry funding of patient and health consumer organisations: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;368:l6925. 10.1136/bmj.l6925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore DA, Loewenstein G. Self-interest, automaticity, and the psychology of conflict of interest. Soc Justice Res 2004;17:189–202. 10.1023/B:SORE.0000027409.88372.b4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sismondo S. Epistemic corruption, the pharmaceutical industry, and the body of medical science. Front Res Metr Anal 2021;6:614013. 10.3389/frma.2021.614013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker L, Fabbri A, Grundy Q, et al. "Asset exchange"—interactions between patient groups and pharmaceutical industry: Australian qualitative study. BMJ 2019;367:l6694. 10.1136/bmj.l6694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arie S, Mahony C. Should patient groups be more transparent about their funding? BMJ 2014;349:g5892. 10.1136/bmj.g5892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moynihan R, Bero L. Toward a healthier patient voice: more independence, less industry funding. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:350–1. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batt S. Who will support independent patient groups? BMJ 2014;349:g6306 https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g5892/rapid-responses 10.1136/bmj.g6306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker L, Brown A, Wells L. Building trust and transparency: health consumer organisation-pharmaceutical industry relationships. Aust Health Rev 2021;45:393–4. 10.1071/AH20206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-055287supp001.pdf (74.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp002.pdf (63.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp003.pdf (4.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp004.pdf (8.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp005.pdf (82.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp006.pdf (102.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-055287supp007.pdf (91.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The raw data used for analysis of information on patient groups’ websites and their policies is available on request.