Abstract

Acquired haemophilia A (AHA) is a rare bleeding disorder with high morbidity and mortality, but it is eminently treatable if diagnosis and treatment are prompt. We report a case of AHA in Southeast Asia following the administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. A man in his 80s developed multiple bruises 2 weeks after his first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Diagnosis was delayed due to his cognitive impairment and low clinical suspicion. This led to a representation with worsening ecchymosis, a left thigh haematoma and symptomatic anaemia. Laboratory testing was notable for an isolated prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time, which remained uncorrected in the mixing test. Further testing confirmed the presence of factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitors and low FVIII titres of 6.7%. He responded to treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone and recombinant activated FVII. Screening for autoimmune diseases and malignancies was negative.

Keywords: COVID-19, geriatric medicine, haematology (incl blood transfusion), vaccination/immunisation, unwanted effects / adverse reactions

Background

Acquired haemophilia A (AHA) occurs due to the development of autoantibodies directed against clotting factor VIII (FVIII). This disease is commonly observed among two groups—pregnant women and the elderly.1 The risk is higher among those above 65 years old and those with malignancies, with a mortality rate approaching 20%.2 Accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment of AHA has been shown to reduce its bleeding mortality risk.3

AHA is known to be associated with autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, malignancies and medications, such as antibiotics and anticonvulsants. However, the majority of cases are idiopathic.4 Studies have reported an association between vaccinations and AHA, namely the seasonal influenza vaccine and H1N1 vaccination.5 6 Nonetheless, a definitive link between the vaccine and AHA remains to be proven.

Case presentation

A man in his 80s was seen in a district hospital clinic with a 4-day history of bruising over the upper and lower limbs. There was no other bleeding tendency. There was no recent history of falls or trauma or a family history of bleeding disorders. He had multiple comorbidities, which included type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease stage 3a, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and glaucoma in both eyes. He had a history of an ischaemic stroke 7 years previously with subsequent cognitive impairment. There was no history of COVID-19 infection. Medications included calcium carbonate, alfuzosin, cardiprin, pantoprazole, atorvastatin, bisoprolol and metformin. The patient had received his first dose of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms. He had no other recent vaccination. On examination, his temperature was 36.8°C, blood pressure 128/68 mm Hg and pulse 73 beats per minute. There were bruises on the right posterior thigh and left upper limb. Blood results demonstrated an isolated prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 90 s (25.4–38.4). The platelet count, international normalised ratio and prothrombin time were normal. His creatinine level was 136 umol/L and liver function was normal. A compression bandage was applied to the haematoma and he was discharged and asked to return for review a week later. He was advised to defer the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

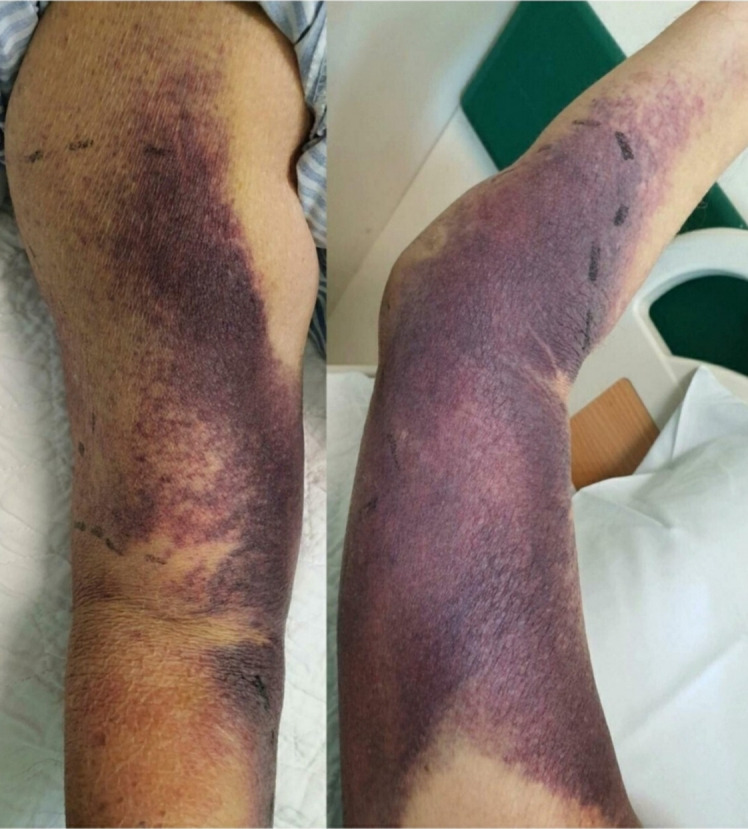

Unfortunately, 5 days later, he presented to the emergency department with tiredness and a painful swollen left lower limb. He appeared frail. He had no constitutional symptoms. No recent falls or trauma were recorded. On examination, his temperature was 36.5°C, blood pressure 127/64 mm Hg, pulse 98 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation 99% while breathing ambient air. There were multiple ecchymoses over his left cubital fossa, left wrist and right arm extending to the forearm (figure 1). There was a painful swelling on the anteromedial aspect of his left thigh with associated oedema (figure 2). The rest of the physical examination was normal. He had a mild cognitive impairment with a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 18/30.

Figure 1.

Ecchymosis over the right medial aspect of the arm and forearm.

Figure 2.

Ecchymosis over the left thigh with intramuscular haematoma.

Investigations

He had severe anaemia with a haemoglobin of 73 g/L (130–180) and an isolated prolonged aPTT at 78.7 s (25.4–38.4). His COVID-19 rapid antigen test on admission was negative.

The other laboratory parameters are tabulated in table 1. The mixing test (patient’s plasma mixed with normal plasma) showed an isolated prolonged aPTT not corrected immediately or at 2 hours postincubation. Subsequent testing yielded a low FVIII assay of 6.7% (62.6–165.3). FVIII inhibitor assay was detectable at 7.5 Bethesda unit (BU). Von Willebrand factor activity and platelet function test were normal, with no anti-PF4 antibody detected. Ultrasound of the left thigh revealed an intramuscular haematoma at the anteromedial part of the thigh measuring 4.0 cm × 6.5 cm × 10.9 cm (AP × W × CC), and posterior part of the thigh measuring 0.8 cm × 1.2 cm × 9.1 cm (AP × W × CC).

Table 1.

Tabulation of laboratory parameters

| Laboratory parameters | Values in unit (normal range) on admission | Values in unit (normal range) 7 weeks later |

| Haemoglobin | 73 g/L (130–180) | 102 g/L (130–180) |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume | 90.6 fL (83–101) | 93.4 fL (83–101) |

| Mean Corpuscular Haemoglobin Concentration | 33.3 g/dL (31.5–34.5) | 33 g/dL (31.5–34.5) |

| White cell count | 11.6×109 /L (4–10) | 7.63×109 /L (4–10) |

| Platelets | 292×103 /µL (150–400) | 280×103 /µL (150–400) |

| aPTT | 78.7 s (25.4–38.4) | 27.1 s (25.4–38.4) |

| Prothrombin time (PT) | 13.1 s (9.62–12.18) | 10.6 s (9.62–12.18) |

| International normalised ratio | 1.26 | 0.97 |

| Creatinine | 134 umol/L (45–84) | – |

| Serum albumin | 31 g/L (35–52) | – |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | 6.2 ng/mL (<3) | – |

| Carbohydrate antigen (CA 19–9) | <2 U/mL (<37) | – |

| Alpha fetoprotein | 1.5 ng/mL (<9) | – |

| Prostate-specific antigen | 9.234 ng/mL (<4) | – |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative | – |

| Beta-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) | 2.1 IU/L (<5) | – |

| C reactive protein | 8.8 mg/L (<5) | – |

| Total iron binding capacity | 41.4 umol/L | – |

| Serum iron | 7.6 umol/L | – |

| Unsaturated iron-binding capacity | 33.8 umol/L | – |

| Serum vitamin B12 level | 103 pmol/L (133–675) | – |

| Serum folate level | 12.9 nmol/L (>14.93) | – |

| Peripheral blood film | Anaemia with increased reticulocytes possibly secondary to underlying bleeding/blood loss. No evidence of haemolysis was seen. White blood cell changes suggest infection or inflammation. | – |

| FVIII assay | 6.7% (50–150) | 365.1% (50–150) |

| FVIII inhibitor | 7.5 BU | <0.5 BU |

| Factor IX assay | 114.7% (86.4–128.4) | – |

aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; FVIII, factor VIII.

Differential diagnosis

Senile purpura can occur in the elderly following minor trauma due to thin sun-damaged skin, especially on the forearms and dorsum of the hands. This patient, however, had an unprovoked left thigh haematoma with an isolated prolonged aPTT effectively excluding senile purpura.

Drug-induced bleeding is unlikely. Although on aspirin, he was not on any anticoagulants, including unfractionated heparin or direct thrombin inhibitors. An antiphospholipid antibody syndrome was unlikely due to his age, and this typically presents with thrombosis. There was no personal or family history of haemostatic disease. There were no features of connective tissue disease. Furthermore, he had a normal platelet count and liver function test. Disseminated intravascular coagulation was excluded in the absence of any infection or sepsis.

A mixing study was performed to differentiate a coagulation factor deficiency from the presence of factor inhibitors. In this case, the test showed a prolonged aPTT uncorrected even after 2 hours of incubation. This implies the presence of a clotting factor inhibitor. He had a low FVIII level, which was only 6.7% (62.6–165.3). FVIII inhibitor titre was detected at 7.5BU, confirming the diagnosis of AHA. His von Willebrand activity was normal.

Further investigations were performed to look for the aetiology of his AHA. Apart from the recent vaccination history, his initial COVID-19 rapid antigen test was negative and the chest X-ray was normal. Tumour markers and screening for autoantibodies were unremarkable (table 1). CT of thorax-abdomen-pelvis did not reveal any malignancy. His esophagogastroduodenoscopy and sigmoidoscopy showed no sign of malignancy.

Treatment

Oral tranexamic acid 500 mg was served immediately at the district hospital with no availability of the bypassing agent. He was transfused with two units of packed red blood cells and four units of fresh frozen plasma. He was then transferred to a specialist centre where aggressive treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg daily for 3 days and a single dose of recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa) 90 µg/kg were given to eliminate inhibitors and achieve haemostasis. The patient responded to this initial treatment and was started on azathioprine 100 mg daily subsequently. He was also commenced on high dose steroids (oral prednisolone 60mg daily) in divided doses to be tapered down over six weeks.

Concurrently, the patient had folate and vitamin B12 deficiency as shown in table 1. He was given oral mecobalamin 500 µg three times a day, as intramuscular cyanocobalamin was contraindicated in this case.

Outcome and follow-up

Given the above, his second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine was deferred. Unfortunately, he developed Covid-19 pneumonia during the third week of tapering dose prednisolone. This resulted in readmission to hospital. Despite this, the AHA remained under control. There was a reduction in the haematoma size and dissipation of the ecchymosis. There was no bleeding episode and his aPTT remained within the normal range. The oral prednisolone was changed to intravenous dexamethasone as advised by the haematologist. This was continued for six days before being converted to oral dexamethasone. He was asked to continue on oral dexamethasone till the end of planned therapy for the AHA (see online supplemental table 1 for details of corticosteroid therapy). The azathioprine was continued at a dose of 100mg daily. He was subsequently discharged well. After 6 weeks of treatment with corticosteroids and azathioprine, his FVIII titres had normalised and FVIII inhibitors were undetectable. Corticosteroids were stopped, whereas oral azathioprine 100 mg daily was continued.

bcr-2021-246922supp001.pdf (38.8KB, pdf)

His clinical course was complicated by an episode of urosepsis and acute urinary retention 2 months after diagnosis. This responded well to intravenous antibiotics and he was scheduled for a renal ultrasound. There was no further bleeding episode and oral azathioprine was reduced to 50 mg daily. At the sixth month of follow-up, he remained in remission while on oral azathioprine 50 mg daily. The haematologist advised further continuation of the azathioprine for a total duration of nine months.

Discussion

Six cases of AHA following COVID-19 vaccination have occurred worldwide.7–10 Interestingly, most of them involved elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. All presented with bleeding within 1–3 weeks after receiving the mRNA vaccine, either Pfizer or Moderna (mRNA-1273). Bleeding was particularly severe among patients who had completed two doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine.7 8 10 Life-threatening bleeding such as a large intramuscular haematoma, haemarthrosis and even a haemothorax were observed. A few of these were treated with rFVIIa and activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) to control the bleeding.8 9 One patient passed away due to an acute gallbladder rupture with active arterial bleeding. Details of those studies are tabulated in table 2. Case studies have reported the appearance of AHA following COVID-19 infection.11–13

Table 2.

Tabulation of previous studies for comparison

| Previous studies | Radwi and Farsi7 | Cittone et al8 | Lemoine et al9 | Gutierrez-Nunez and Torres10 | ||

| Location | Middle East (Saudi arabia) |

Europe (Switzerland) |

North America | Country of occurrence not stated. (Author’s communication details not available) |

||

| Age | 69 | 85 | 86 | 72 | 70 | 43 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Female |

| Comorbid |

|

|

|

|

|

– |

| Type of vaccine | Pfizer mRNA | Moderna (mRNA-1273) | Moderna COVID-19 (mRNA-1273) | Moderna COVID-19 (mRNA-1273) | Moderna COVID-19 (mRNA-1273) | Pfizer mRNA |

| Total dose received | Two doses | Two doses | Two doses | One dose | One dose | Two doses |

| Onset of symptoms | Nine days after the first dose, the patient developed a spontaneous mild bruise over the left wrist. After the second dose, the patient developed spontaneous ecchymosis on the left forearm and elbow, ecchymosis on the right thigh (after intramuscular injection and minor trauma), and left anteromedial thigh intramuscular haematoma. |

One week after the first dose, the patient developed right forearm and right thigh haematoma, with bilateral knee haemarthrosis. After the second dose, the patient developed a large haematoma of the right iliopsoas muscle and free fluid in the right lower abdomen. |

Three weeks after the second dose, the patient had a fall with a right-sided haemothorax and fractures of the 9th, 10th and 11th ribs. | Two weeks after the first dose, the patient developed extensive cutaneous bruises. 24 days after the first dose, the patient developed multiple large cutaneous haematomas. |

Eight days after the first dose, he developed extensive ecchymosis on the right upper limb, ecchymosis on the left forearm and right lower extremity. | Three weeks after the second dose, the patient developed bilateral extremities haematomas. |

| aPTT (sec) | 115.2 | 49 | Not stated. | 184 | 57.5 | 86.1 |

| FVIII level | 1% → 5% | Not detectable | 23% → 178% | Not detectable → 5% (after the third dose of rituximab) |

0.03 IU/mL | <5% |

| FVIII inhibitor titre (BU) | 80 → 2 | 2.2 | 1.01 | 12.4 → 5.6 (after the third dose of rituximab) | 39.9 | 78.4 |

| Use of aPCC/ rFVIIa | – | rFVIIa and aPCC | rFVIIa and aPCC | rFVIIa for 7 days | rFVIIa and aPCC | – |

| Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Outcome | Good | The patient had an acute gallbladder rupture with active arterial bleeding and passed away. | Good | Good | Good | Not stated. |

aPCC, activated prothrombin complex concentrate; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; FVIII, factor VIII; rFVIIa, recombinant activated factor VII.

Our case highlights the appearance of AHA following the administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia. The onset of the patient’s symptoms shortly after vaccination in the absence of any other precipitating factor points towards a vaccine-induced AHA. We postulate that the vaccination triggered an autoimmune response. Other autoimmune phenomena have been reported following vaccination, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome and immune thrombocytopenic purpura.14 15 The pathophysiology of postvaccine AHA remains unclear. Vaccines are known to trigger the activation of non-specific antibodies and stimulate autoantibody production via pre-existing B cells. It is postulated that antigenic mimicry can occur, although following secondary exposure.

Under available guidelines, treatment of bleeding in patients with suspected or confirmed AHA should be carried out at a specialist centre.1 Currently, aPCC, rFVIIa and recombinant porcine FVIII can be considered as appropriate first-line treatments. Propensity score-matched analysis of registry data on these three agents did not show a superiority of one drug over the others.3 4 The current mainstay of inhibitor eradication includes immunosuppression with steroids and cytotoxic agents, alone or in combination. The most widely used agents include prednisolone and cyclophosphamide. However, cyclophosphamide was deemed unsuitable for our patient, given the risk of myelosuppression and infection.

The 2020 international AHA guideline recommends initiating immunosuppressive therapy (IST) in all AHA patients promptly following diagnosis. The guideline recommends the use of oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day for a maximum of 4–6 weeks.1 However, clinicians should individualise the use of IST among frail patients with AHA. The GTH-AH 01/2010 study protocol has reported that IST-related mortality, in particular infection, outweighs the risk of fatal bleeding in AHA. Patients with a poor WHO performance status at presentation were found to have a four-fold increased risk of mortality.16

Given the patient’s cognitive impairment and frailty, a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) from the outset might have facilitated an earlier diagnosis. CGA is a multidimensional multidisciplinary diagnostic process to determine an elderly patient’s medical, psychological and functional capability with the ultimate goal of treating acute illness while maintaining function.17 18 An explicit care plan is developed by setting goals, assigning responsibility and determining a timeline to review progress. It is important to ascertain a patient’s premorbid functional status to achieve a reasonable rehabilitation goal. History taking can be challenging in the elderly due to accompanying sensory and/or cognitive impairment. Therefore, a collateral history from a caretaker is essential. A meta-analysis of randomised control trials has demonstrated that inpatient CGA brings a significant reduction in mortality or functional decline at 6 months.19

Randomised clinical trials have demonstrated that the mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccines are safe.20 21 However, only a quarter of the trial participants were aged 65 and above.20 AHA remains a rare condition. Despite a temporal association between the COVID-19 vaccine and AHA, a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established in this case report. Further study is warranted. The elderly should be encouraged to accept vaccination as the benefits far outweigh the risk of COVID-19 infection. However, careful clinical assessment and close post-vaccination monitoring are advised.

Patient’s perspective.

I am concerned about my parents’ safety during this COVID-19 pandemic and thus advised them to take the vaccine. I am convinced that the vaccine can protect them from becoming seriously ill if an infection occurs. However, I had never expected that this rare side effect could be serious and require hospital admission. My father has cognitive impairment and has difficulty expressing his concerns or feelings. It was an incidental finding that I noticed his bruises 1 day and I was puzzled since he had not had any recent falls. Initially, I took him to a clinic in the district hospital and the doctor performed some blood tests. The doctor reassured me that this was unlikely to be a bleeding disorder at this old age. However, as his bruises increased in size and his left thigh became swollen, he became more tired and I decided to bring him to the hospital again. The attending doctor performed a variety of tests including an ultrasound. I am glad that the doctor was finally able to find the diagnosis. I feel relieved when I see the bruises improving and my father responding to treatment in a specialised centre.

Learning points.

Early comprehensive geriatric assessment with a coordinated and integrated care plan should be implemented for frail elderly patients.

Clinicians should consider recent vaccination history in patients presenting with idiopathic acquired haemophilia A.

A high index of suspicion in nonbleeding elderly with isolated prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time and not on anticoagulation.

Caution in giving immunosuppressive therapy to frail elderly patients with close monitoring to ensure safety.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. We would also like to thank Dr Veena Selvaratnama and her laboratory staff for her contributions in analysing his blood sample for factor titre, inhibitor assay as well as platelet function and Von Willebrand analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: LAV, EAS-Y and ANK involved in clinical management of the patient. LAV conducted the patient’s son interview. TMSTJ involved in the supervision of geriatric management, proofreading and english editing of this report. All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from next of kin.

References

- 1.Tiede A, Collins P, Knoebl P, et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia a. Haematologica 2020;105:1791–801. 10.3324/haematol.2019.230771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bitting RL, Bent S, Li Y, et al. The prognosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2009;20:517–23. 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32832ca388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, et al. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European acquired haemophilia registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost 2012;10:622–31. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado J, Jimenez-Yuste V, Hernandez-Navarro F, et al. Acquired haemophilia: review and meta-analysis focused on therapy and prognostic factors. Br J Haematol 2003;121:21–35. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moulis G, Pugnet G, Bagheri H, et al. Acquired factor VIII haemophilia following influenza vaccination. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:1069–70. 10.1007/s00228-010-0852-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirrotta MT, Bernardeschi P, Fiorentini G. A case of acquired haemophilia following H1N1 vaccination. Haemophilia 2011;17:no. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radwi M, Farsi S. A case report of acquired hemophilia following COVID-19 vaccine. J Thromb Haemost 2021;19:1515–8. 10.1111/jth.15291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cittone MG, Battegay R, Condoluci A, et al. The statistical risk of diagnosing coincidental acquired hemophilia A following anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Thromb Haemost 2021;19:2360–2. 10.1111/jth.15421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemoine C, Giacobbe AG, Bonifacino E. A case of acquired haemophilia A in a 70-year-old post COVID-19 vaccine. Haemophilia: the Official Journal of the World Federation of Hemophilia, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez-Nunez J, Torres G. " Dark skin"-acquired hemophilia a after pfizer-biontech covid-19 vaccine. Chest 2021;160:A1384. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.1265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini M, Glingani C, De Donno G, et al. The first case of acquired hemophilia A associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Am J Hematol 2020;95:E197-E198. 10.1002/ajh.25865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hafzah H, McGuire C, Hamad A. A case of acquired hemophilia A following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cureus 2021;13:e16579. 10.7759/cureus.16579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang KY, Shah P, Roarke DT, et al. Severe acquired haemophilia associated with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e242884. 10.1136/bcr-2021-242884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souayah N, Nasar A, Suri MFK, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome after vaccination in United States: data from the centers for disease control and prevention/food and drug administration vaccine adverse event reporting system (1990-2005). J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2009;11:1–6. 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181aaa968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cines DB, Bussel JB. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine–Induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2021;384:2254–6. 10.1056/NEJMe2106315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiede A, Klamroth R, Scharf RE, et al. Prognostic factors for remission of and survival in acquired hemophilia A (AHA): results from the GTH-AH 01/2010 study. Blood 2015;125:1091–7. 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernabei R, Venturiero V, Tarsitani P, et al. The comprehensive geriatric assessment: when, where, how. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2000;33:45–56. 10.1016/S1040-8428(99)00048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer K, Onder G. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: benefits and limitations. Eur J Intern Med 2018;54:e8–9. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d6553. 10.1136/bmj.d6553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;384:403–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1761–73. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bcr-2021-246922supp001.pdf (38.8KB, pdf)