Abstract

The current cross-sectional study investigates whether pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between ethnicity/race and pain, disability and physical function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Furthermore, this study examined mediation at 2-year follow-up. Participants included 187 community-dwelling adults with unilateral or bilateral knee pain who screened positive for knee osteoarthritis. Participants completed several self-reported pain-related measures and pain catastrophizing subscale at baseline and 2-year follow-up. Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) adults reported greater pain, disability, and poorer functional performance compared to their non-Hispanic White (NHW) counterparts (Ps < .05). NHB adults also reported greater catastrophizing compared to NHW adults. Mediation analyses revealed that catastrophizing mediated the relationship between ethnicity/race and pain outcome measures. Specifically, NHB individuals reported significantly greater pain and disability, and exhibited lower levels of physical function, compared to NHW individuals, and these differences were mediated by higher levels of catastrophizing among NHB persons. Catastrophizing was a significant predictor of pain and disability 2-years later in both ethnic/race groups. These results suggest that pain catastrophizing is an important variable to consider in efforts to reduce ethnic/race group disparities in chronic pain. The findings are discussed in light of structural/systemic factors that may contribute to greater self-reports of pain catastrophizing among NHB individuals.

Keywords: Pain catastrophizing, ethnicity/race, knee osteoarthritis, chronic pain, disability

Symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent joint disease, occurring in approximately 14 million adults in the United States (US), with more than half of these cases diagnosed as advanced.18 Knee OA prevalence has doubled in the US since the mid-20th century91 and is projected to further increase as a result of the aging population and the rising levels of obesity, among other risk factors.18,40,83 Knee OA causes debilitating chronic joint pain, functional limitation (e.g., reduced walking distance) and disability (e.g., inability to work).5,19,38,41,72,78 Historically, knee OA has been conceptualized as a regional pain condition driven primarily by peripheral joint changes; however, radiographic findings are not strong predictors of clinical symptoms (e.g., knee pain).6,33,41,48 Therefore, the focus on structural pathology as the cause for clinical symptoms fails to fully explain OA-related pain and disability,14 which implicates other risk factors (e.g., psychosocial factors) as potentially important contributors to OA-related pain and disability outcomes.39

Symptomatic knee OA is highly prevalent, and expected to rise, among adults from racial/ethnic marginalized groups.16 Evidence indicates that non-Hispanic Black (NHB) adults have a higher prevalence of both radiographic and symptomatic knee OA compared to non-Hispanic White (NHW) adults.20,43,60,75 For example, in a recent meta-analysis, researchers found that NHB individuals experience greater pain and have higher rates of disability due to knee OA compared to their NHW counterparts.86 NHB individuals report greater pain severity, higher levels of pain-related physical and psychosocial disability,4 and more severe functional limitations,90 and these pain disparities have been demonstrate to persist over time.87

Multiple biological and psychosocial factors likely contribute to the health disparities in OA-related knee pain, disability, and functional impairment. One psychosocial factor, pain catastrophizing, has been consistently associated with poor OA-related outcomes.51,80 Pain catastrophizing is an increasingly controversial term applied to a pattern of cognitive and affective appraisal of pain characterized by the tendency to attend to, and magnify, the threat value of painful stimuli and to feel helpless in the context of pain.63 Substantial evidence links pain catastrophizing with greater clinical pain and self-reported disability, and poorer functional performance.12,74,76 Moreover, prior research indicates that NHB individuals engage in pain catastrophizing as a pain coping strategy more frequently than their NHW peers.57,58,69 However, greater use of pain catastrophizing may be due to the impact of health disparities as the result of structural/systemic barriers that influence pain and disability in ethnic/racial minority groups.3,29,51,85 Therefore, the responses to the pain catastrophizing items may reflect consequences of structural/systemic barriers that disproportionately impact Black and White persons. Furthermore, previous studies have not evaluated pain catastrophizing over a longitudinal period, to better understand its influence on pain and disability over time. Given that pain catastrophizing is greater in NHB individuals and is also associated with greater OA-related pain and disability, it is possible that pain catastrophizing mediates ethnic/race group differences in OA-related pain and disability.

The current study aims to examine whether pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between ethnicity/race and OA-related pain, disability, and functional impairment at baseline and during a 2-year follow-up among NHB and NHW adults with self-reported knee pain. We tested the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1: NHB participants will report higher levels of pain catastrophizing, clinical pain and disability, and exhibit lower levels of physical function compared to NHW participants. Hypothesis 2: Pain catastrophizing will mediate ethnic/race group differences in clinical pain, disability, and physical function at baseline. Hypothesis 3: Pain catastrophizing will mediate ethnic/race group differences in pain and disability over a 2-year follow-up period. The findings are discussed in light of structural/systemic factors that may contribute to greater self-reports of pain catastrophizing among NHB individuals.

Methods

Study Overview

The current study analyzed data from a larger longitudinal observational cohort study titled Understanding Pain and Limitations in OsteoArthritic Disease − Second Cycle, (UPLOAD-2) that was conducted at the University of Florida (UF) and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) between August 2015 and May 2017.

Participants

Participants were 187 community-dwelling adults who self-identified as NHB or NHW, presented with unilateral or bilateral knee pain, and screened positive for clinical knee OA.2

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at UF and UAB. Participants completed a standardized telephone screening whereby sociodemographic and physical health data were obtained to determine initial eligibility. Sociodemographic information included self-reported questions about potential participant’s sex, age, ethnic/racial identity, and a brief health history screening including symptoms of knee OA. This screening questionnaire used to determine symptoms of knee OA showed 87% sensitivity and 92% specificity for radiographically confirmed symptomatic knee OA.68

Participants meeting inclusion criteria were brought into the laboratory and were consented prior to data collection. Participants then provided additional sociodemographic information (e.g., educational level obtained, current income, insurance status), anthropometric measurements (e.g., height, weight) were obtained and participants completed the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Self-report questionnaires assessing pain catastrophizing, clinical pain, and pain-related disability were administered electronically via email prior to the subsequent visits of this multi-session protocol. However, if the participant did not have access to a computer to complete the questionnaires electronically, the questionnaires were completed at the beginning of the next laboratory visit. After completion of baseline sessions, participants were contacted by telephone and/or email on a quarterly basis for up to 2 years (total of 7 follow-up contacts) to complete a pain and disability questionnaire.

Participants were recruited through the community via multiple advertisement methods (e.g., posted fliers), health fairs or other community events, radio advertisement targeted for specific audience, bus advertisement, clinic-based methods partnership with local clinics, and the University of Florida sponsored community engagement program (HealthStreet) (Supplemental Table S1 for recruitment strategies by ethnicity/race). Participants were excluded based on the following: 1) knee replacement or other clinically significant surgery to the arthritic knee; 2) uncontrolled hypertension; 3) heart disease; 4) peripheral neuropathy; 5) systemic rheumatic disorders; 6) neurological diseases; 7) significantly greater pain in body sites other than in the knee; 8) daily opioid use; 9) hospitalization within the preceding year for psychiatric illness; or 10) pregnant or nursing.

Measures

Outcome Variables

Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire-Revised (SF-MPQ-2).

The SF-MPQ-2 is a self-reported measure that has evidenced adequate reliability and validity in individuals with chronic pain conditions.21 Participants completed a modified version of the SF-MPQ-2, instructing them to rate the extent to which they experienced each of 22 pain descriptors (e.g., throbbing pain, shooting pain, hot-burning pain, punishing-cruel pain) in their most bothersome knee, during the past week. Participants used an 11-point numeric rating scale (0 = “none” to 10 = “worst possible”) to describe their pain intensity. The total SF-MPQ-2 score (current study) is computed as an average across all questions.

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC).

The WOMAC is a 24-item self-administered assessment of knee OA symptoms over the past 48 hours.7 Severity of symptoms are rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 indicating “None” and 4 indicating “Extreme”) with scores on the pain subscale ranging from 0 to 20 and scores on the physical function subscale ranging from 0 to 68, with higher scores reflecting greater severity. The WOMAC is a well-validated and reliable (Cronbach’s α: pain subscale = 0.89; physical function subscale = 0.97) instrument.7

Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS).

The GCPS is a seven-item self-administered assessment of knee pain (pain intensity), and knee pain interference (disability) experienced over the past 6 months.22 Characteristic pain intensity is the average of the current, average, and worst knee pain (0−10 scale), multiplied by 10 (Range 0−100) to generate a characteristic pain intensity score. Using the same scale, participants rated the degree to which their knee pain interfered with daily activities during the past six months, which was averaged and multiplied by 10 to generate a disability score. Higher scores reflecting greater knee symptomatology.22

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).

The SPPB is a standardized measure of lower-extremity function that includes three performance tests: standing balance, 4-meter gait speed, and chair-rising.32 Each measure is scored from 0 (worst performance) to 4 (best performance), and a total score (range: 0−12) is calculated as the sum of all the items. Lower scores indicate poorer function and greater disability.23,32 The total score was used in analyses.

Quarterly Pain Assessment.

Participants completed online or telephone quarterly assessments of self-reported knee pain over the past week using three items from the GCPS to assess pain severity (“knee pain at its worst” and “knee pain on average” in the last week, and “knee pain right now”). Pain items were averaged and multiplied by 10 to create a pain intensity score. Participants also self-reported how much knee pain interfered with their general activities during the past week (1 item, 0−10 scale).

Mediator Variable

Pain catastrophizing subscale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire-Revised (CSQ-R). The pain catastrophizing subscale consists of 6 items 66 assessing the frequency of pain-related catastrophic thoughts (e.g., “I worry all the time about whether the pain will end”), on a 0 (“never do that”) to 6 (“always do that”) scale. Pain catastrophizing scores range from 0–6. Responses across items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater pain catastrophizing.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL), and R version 3.6.2. Data were checked for normality, outliers, and missing values prior to analysis. Ethnic/racial differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were assessed using chi-square (χ2) tests for dichotomous variables and independent samples t-tests for continuous variables. Pearson correlations were conducted to examine associations between pain catastrophizing and outcome variables (clinical pain, disability, and functional performance) separately by ethnicity/race. Fisher’s r-to-z tests were conducted to examine potential ethnic/race group differences in relationship patterns between pain catastrophizing and outcome variables. A one-way between-groups analysis of covariance was conducted to assess differences across ethnicity/race and outcome variables. Effect size estimates associated with F tests were calculated using partial eta squared values and classified as follows: (small = 0.01, medium = 0.06, and large = 0.14).

The 2-year follow-up data were analyzed to obtain the area under-the-curve (AUC). A total of 187 participants completed the quarterly questionnaires. Thirty-five participants were removed from the analyses due to missing data (>3.5 missing out of 7). Therefore, 152 participants remained in the analyses. Additional missing data were imputed by K-nearest-neighbor method using R package impute,34 which calculated the missing data of a subject by its K closest neighboring subjects. The data was fitted to a smoothing spline15 curve to estimate the trajectory of pain intensities and pain interference, respectively and the total pain intensity and pain interference were calculated by the AUC of the fitted spline curve. The AUC provides a robust estimate of total pain measurement since the pain measurement between adjacent visits were less likely to fluctuate.

Hayes’ PROCESS macro SPSS36 was used to examine the simple mediation model (Model 4). This statistical approach employs bootstrapping to conduct inference tests for the indirect effects.35 The 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (CI) is based on 5,000 bootstrap samples to generate the path estimates and the indirect effects. Results were considered statistically significant when zero was not contained in the 95% CI. Study site, age, gender, education, BMI, income, and marital status were included as covariates in all analysis of covariance and mediation analyses. Additionally, baseline GCPS pain intensity was included as a covariate in AUC pain model, while baseline GCPS interference was included as a covariate in GCPS interference model in the 2-year follow-up mediational analyses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented by ethnicity/race group (Table 1). NHW participants were significantly older, with higher income (χ2 = 23.57, P = .01), higher educational attainment (χ2 = 12.97, P = .02), and higher rates of marriage (χ2 = 20.05, P < .01) compared to NHB participants. NHB participants reported higher pain catastrophizing (M = 1.7, SD = 1.3) compared to NHW participants (M = 0.9, SD = 1.1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants by Ethnicity/Race

| NHB (N = 96) | NHW (N = 91) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M or N (SD or%) | M or N (SD or%) | P | |

|

| |||

| Age (y)* | 56.5(6.6) | 59.6(8.6) | .01 |

| Study site | .21 | ||

| UF | 57(47.5) | 63(52.5) | |

| UAB | 39(58.2) | 28(41.8) | |

| Sex | .35 | ||

| Female | 57(48.3) | 61(51.7) | |

| Male | 39(56.5) | 30(43.5) | |

| Income* | <.01 | ||

| $0-$9,999 | 36(38.7) | 18(20.0) | |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 15(16.1) | 10(11.1) | |

| $20,000-$29,999 | 16(17.2) | 9(10.0) | |

| $30,000-$39,999 | 5(5.4) | 3(3.3) | |

| $40,000-$49,999 | 3(3.2) | 10(11.1) | |

| $50,000-$59,999 | 5(5.4) | 11(12.2) | |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 6(6.5) | 9(10.0) | |

| $80,000-$99,999 | 4(4.3) | 6(6.7) | |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 2(2.2) | 10(11.1) | |

| >150,000 | 1(1.1) | 4(4.4) | |

| Education* | .02 | ||

| Some school, <high school | 9(9.4) | 4(4.4) | |

| High school degree | 47(49.0) | 31(34.1) | |

| Associates degree | 19(19.8) | 14(15.4) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 13(13.5) | 24(26.4) | |

| Master's degree | 6(6.3) | 13(14.3) | |

| Doctoral/professional | 2(2.1) | 5(5.5) | |

| Marital status* | <.01 | ||

| Married | 24(25.5) | 43(47.3) | |

| Widowed | 10(10.6) | 4(4.4) | |

| Divorce | 27(28.7) | 26(28.6) | |

| Separated | 8(8.5) | 1(1.1) | |

| Never married | 24(25.5) | 12(13.2) | |

| Living with partner | 1(1.1) | 5(5.5) | |

| Insurance status | .58 | ||

| No | 15(15.6) | 15(16.5) | |

| Yes | 81(84.4) | 75(82.4) | |

| Knee pain duration | .26 | ||

| <6 mo | 4(4.2) | 6(6.7) | |

| 6 to 12 mo | 10(10.4) | 5(5.6) | |

| 1 to 3 y | 27(28.1) | 19(21.1) | |

| 3 to 5 y | 16(16.7) | 11(12.2) | |

| >5 y | 39(40.6) | 49(54.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.9(7.8) | 31.2(7.5) | .15 |

| Pain catastrophizing* | 1.7(1.3) | 0.9(1.1) | <.01 |

Abbreviation: NHB, non-Hispanic black; NHW, non-Hispanic white; UF, university of florida; UAB, university of birmingham at alabama; BMI, body mass index.

Note:

P < .05.

Ethnic/Race Differences in Pain, Disability and Functional Performance

There were significant ethnic/race differences across all clinical pain and disability outcome measures (ps<.05), indicating that NHB participants reported higher pain and greater disability compared to NHW participants (Table 2). These effects remained significant even after controlling for study site, age, gender, education, BMI, income, and marital status. However, there was no significant ethnic/race difference in functional performance (P = .11).

Table 2.

Inferential Statistics for Measures of Pain, Disability and Function

| ADJUSTED |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHB | NHW | COMPARISON |

||

| M(SD) | M (SD) | F | ηp2 | |

|

| ||||

| SF-MPQ-2 total | 3.5(2.3) | 1.7(1.8) | 13.31** | .08 |

| WOMAC pain | 9.2(4.0) | 6.6(4.3) | 4.63* | .03 |

| WOMAC physical function | 30.4(13.7) | 20.1(13.8) | 9.28** | .05 |

| GCPS pain intensity | 67.0(20.5) | 44.1(20.3) | 28.16** | .14 |

| GCPS interference | 57.3(27.8) | 37.6(29.7) | 7.63** | .04 |

| SPPB function (0–12) | 9.0(1.8) | 9.7(1.5) | 2.57 | .02 |

Abbreviation: NHB, non-hispanic black; NHW, non-hispanic white; SF-MPQ-2, short form McGill pain questionnaire - revised; WOMAC, western ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index; GCPS, graded chronic pain scale; SPPB, short physical performance battery;

NOTE: Covariates, study site, age, gender, BMI, education, income, and marital status.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Correlations between Pain Catastrophizing and Clinical Characteristics by Ethnicity/Race

Pain catastrophizing was moderately to strongly correlated with pain and disability in both groups (Table 3). However, pain catastrophizing was weakly correlated with functional performance in NHW participants. Fisher’s r-to-z transformation tests revealed no evidence of differential associations between pain catastrophizing and outcome variables by ethnicity/race (Table 3). Supplementary Figures S1a–S1f provide scatterplots of pain catastrophizing with outcome variables (e.g., pain, disability, and function) separated by ethnicity/race.

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations and Fisher’s r-to-z Transformation Among Pain Catastrophizing and Clinical Characteristics of NHB and NHW Participants

| ZERO-ORDER CORRELATION |

FISHER'S R-TO-Z TESTS | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHB PARTICIPANTS | NHW PARTICIPANTS | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Pain catastrophizing | - | - | - | ||||||||||||

| SF-MPQ-2 Total | .53** | - | .70** | - | −1.9 | ||||||||||

| WOMAC pain | .43** | .70** | - | .60** | .81** | - | −1.56 | ||||||||

| WOMAC physical function | .46** | .71** | .84** | - | .60** | .75* | .88** | - | −1.32 | ||||||

| GCPS pain intensity | .45** | .65** | .60** | .69** | - | .63** | .76** | .73** | .69** | - | −1.73 | ||||

| GCPS Interference | .48** | .63** | .58** | .64** | .71** | - | .51** | .59** | .54** | .58** | .66** | - | −0.27 | ||

| SPPB function | −.44** | −.31** | −.27** | −.37** | −.25** | −.45** | - | −.22* | −.16 | −.25* | −.39** | −.18 | −.34** | - | −1.67 |

Abbreviation: SF-MPQ-2, short form McGill pain questionnaire - revised; WOMAC, western ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index; GCPS, graded chronic pain scale; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

NOTE: Fisher’s r-to-z transformation tests (p two-tailed).

P < .05.

P < .01.

Mediation Analyses

Separate mediation models were conducted on the following outcome variables: 1) pain measures including SF-MPQ-2, WOMAC Pain, and GCPS Pain Intensity; 2) disability measures including WOMAC Physical Function and GCPS interference; and 3) functional performance measure including SPPB Function and outcome variables used over the follow-up period were: 1) pain measure include AUC GCPS Pain Intensity and 2) disability measure include AUC GCPS Pain Interference. Each of the eight mediation models retained the same predictor (ethnic/race group) and mediator (pain catastrophizing). All models controlled for study site, age, gender, education, BMI, income, and marital status. In addition, baseline GCPS pain intensity and baseline GCPS interference were included as covariates in the 2-year follow-up mediation analyses.

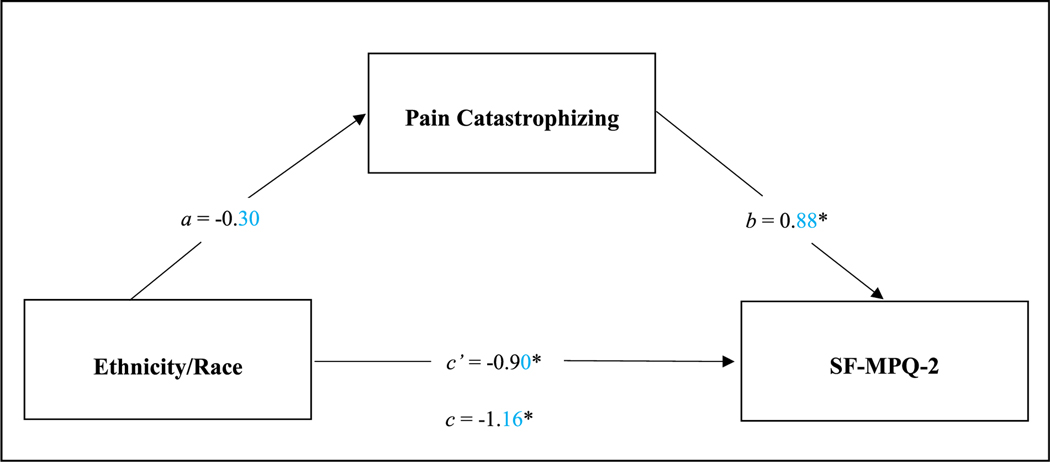

SF-MPQ-2

Model one predicted significant variance in pain, (R2 = .30, F(8,157) = 8.49, P < .001) (Fig 1). Ethnicity/race was not associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −1.69, P = .094, CI = [−.651, .052]), and pain catastrophizing was positively associated with pain, (t = 7.04, P < .001, CI = [.632, 1.125]). This indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the SF-MPQ-2 was not statistically significant [95% CI = −.609, .060].

Figure 1.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences SF-MPQ-2 Total, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. SF-MPQ-2, Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire-revised. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

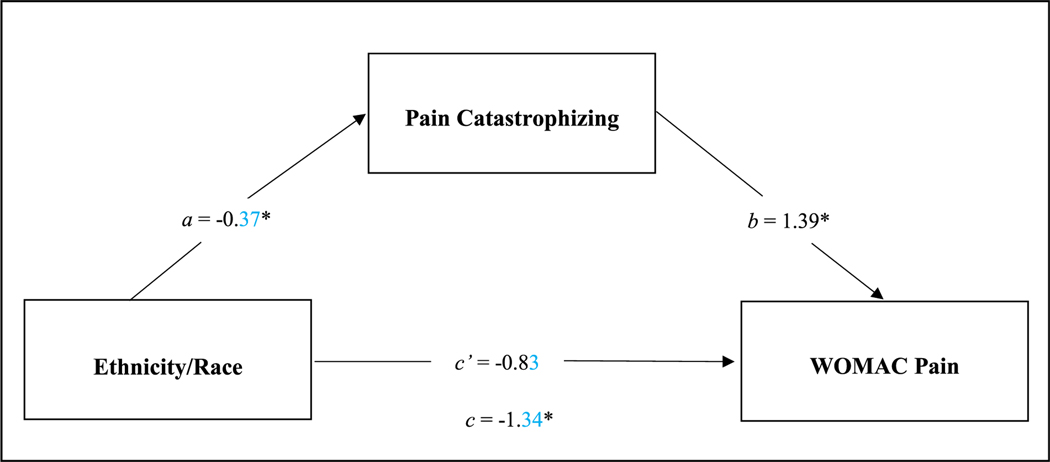

WOMAC Pain

Model two accounted for significant variance in WOMAC pain, (R2 = .25, F(8,166) = 6.76, P < .001) (Fig 2). Ethnicity/race was associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −2.07, P = .040, CI = [−.720, −.017]), indicating higher pain catastrophizing among NHB participants, and pain catastrophizing was positively associated with clinical pain, (t = 5.55, P < .001, CI = [.897, 1.887]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the WOMAC pain subscale [95% CI = −1.133, −.012].

Figure 2.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences WOMAC Pain, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

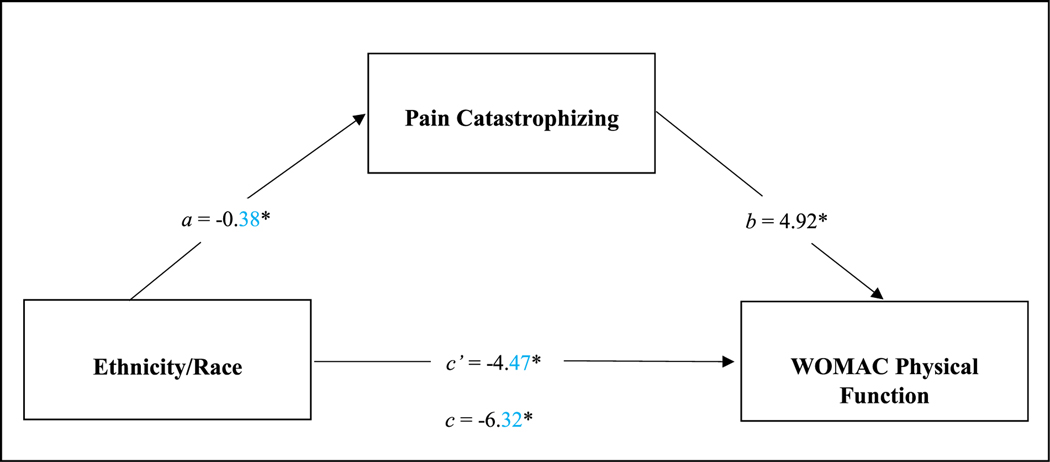

WOMAC Physical Function

Model three was predictive of significant variance in WOMAC physical function, (R2 = .27, F(8,167) = 7.87, P < .001) (Fig 3). Ethnicity/race was associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −2.12, P = .036, [CI = −.726, −.026]), indicating higher pain catastrophizing among NHB participants, and pain catastrophizing was positively associated with physical function, (t = 5.98, P < .001, [CI = 3.296, 6.545]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race mediated through pain catastrophizing on the WOMAC physical function subscale [95% CI = −4.116, −.061].

Figure 3.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences WOMAC Physical Function, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

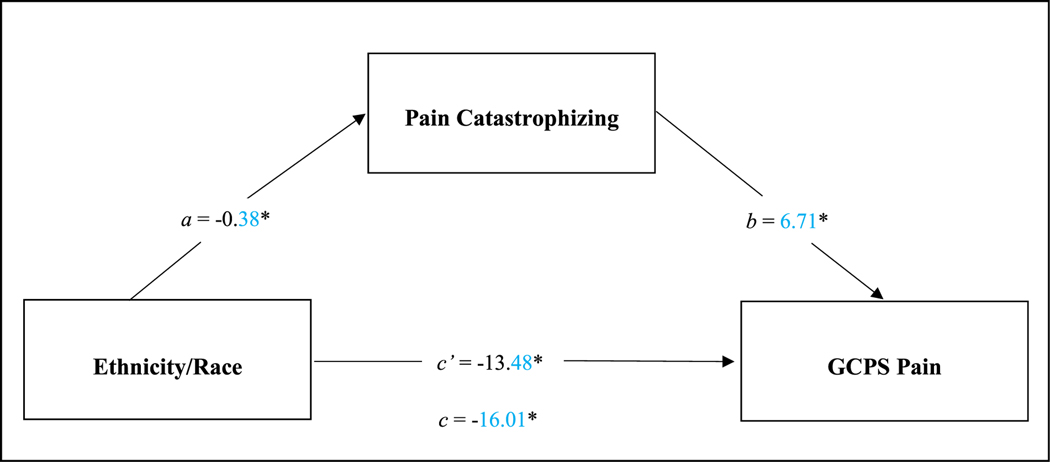

GCPS Pain Intensity

Model four predicted significant variance in GCPS Pain intensity, (R2 = .39, F(8,167) = 13.60, P < .001) (Fig 4). Ethnicity/race was associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −2.12, P = .036, [CI = −.726, −.026]), indicating higher pain catastrophizing among NHB participants, and pain catastrophizing positively associated with pain intensity (t = 5.54, P < .001, [CI = 4.318, 9.103]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the GCPS pain intensity [95% CI = −5.344, −.100].

Figure 4.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences GCPS Pain, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. GCPS, Graded Chronic Pain Scale. Covariates include, study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

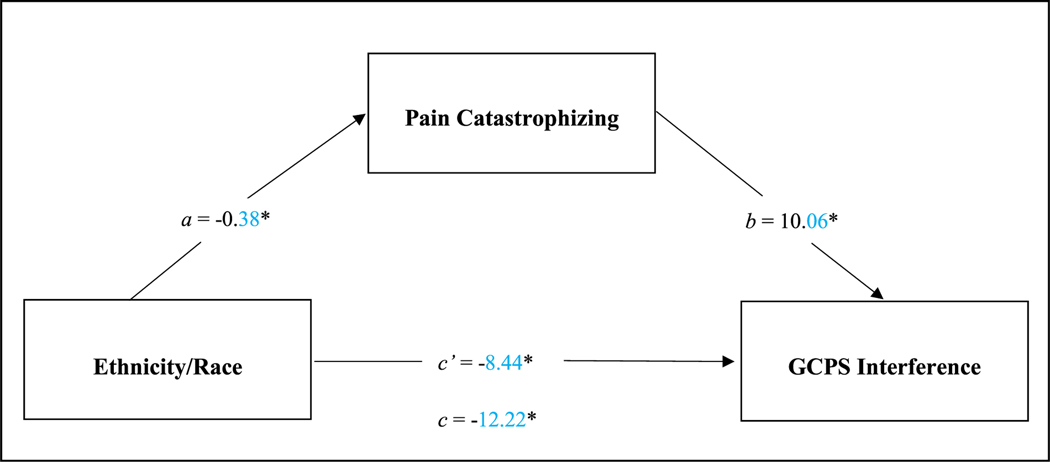

GCPS Interference

Model five was predictive of significant variance in GCPS interference, (R2 = .23, F(8,167) = 6.14, P < .001) (Fig 5). Ethnicity/race was associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −2.12, P = .036, [CI = −.726, −.026]), indicating higher pain catastrophizing among NHB participants, and pain catastrophizing was positively associated with disability, (t = 5.69, P < .001, [CI = 6.567, 13.554]) This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the GCPS pain interference [95% CI = −8.146, −.145].

Figure 5.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences GCPS Interference, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. GCPS, graded chronic pain scale. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

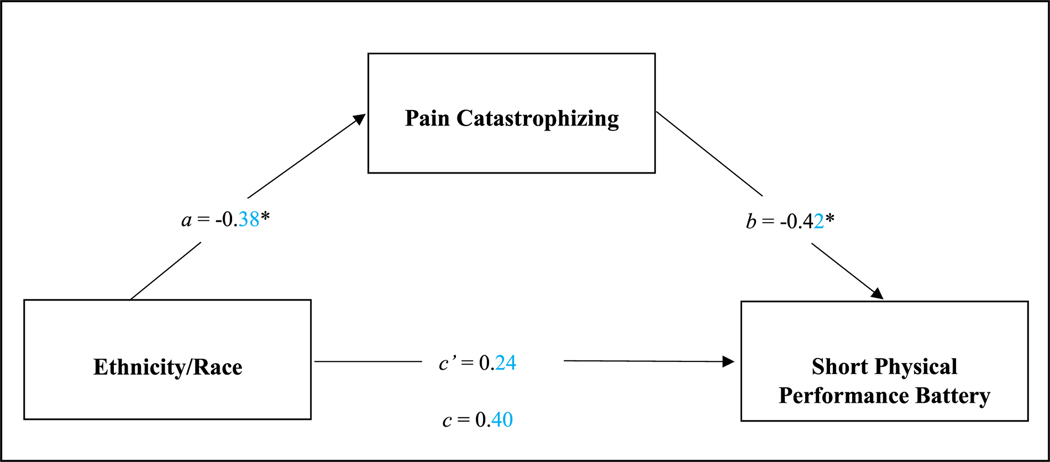

SPPB

Model six was predictive of significant variance in SPPB functional performance, (R2 = .25, F(8,167) = 6.79, P < .001) (Fig 6). Ethnicity/race was associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −2.12, P = .036, [CI = −.726, −.026]), indicating higher pain catastrophizing among NHB participants, and pain catastrophizing was negatively associated with function, (t = −4.10, P < .001, [CI = −.625, −.218]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on SPPB functional performance [95% CI = .004, .389].

Figure 6.

Mediation model show how ethnicity/race group influences SPPB, mediated through pain catastrophizing. Note: *P < .05. SPPB, short performance physical battery. Covariates include, study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, and marital status.

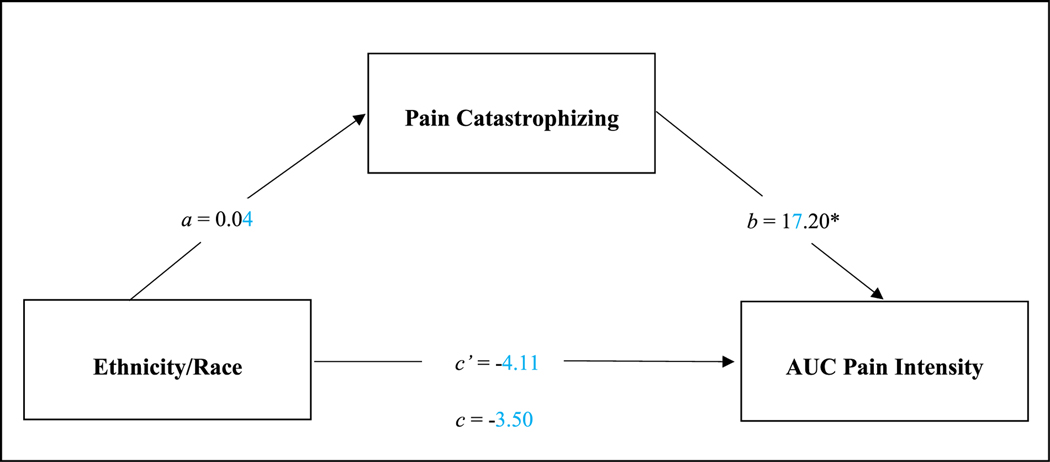

AUC GCPS Pain Intensity

Model seven was predictive of significant variance in AUC GCPS pain intensity, (R2 = .55, F(9,133) = 17.99, P < .001) (Fig 7). Ethnicity/race was not associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = .17, P = .862, [CI = −.365, .436]), however, pain catastrophizing was positively associated with AUC pain intensity, (t = 2.14, P = .034, [CI = 1.304, 33.090]), suggesting higher pain catastrophizing was predictive of greater pain intensity up to two years later. This model showed a non-significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the AUC GCPS pain intensity [95% CI = 7.905, 10.068].

Figure 7.

Mediation model show pain catastrophizing influences AUC knee pain intensity AUC. Note: *P < .05. AUC, area under the curve. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, marital status, and GCPS pain intensity.

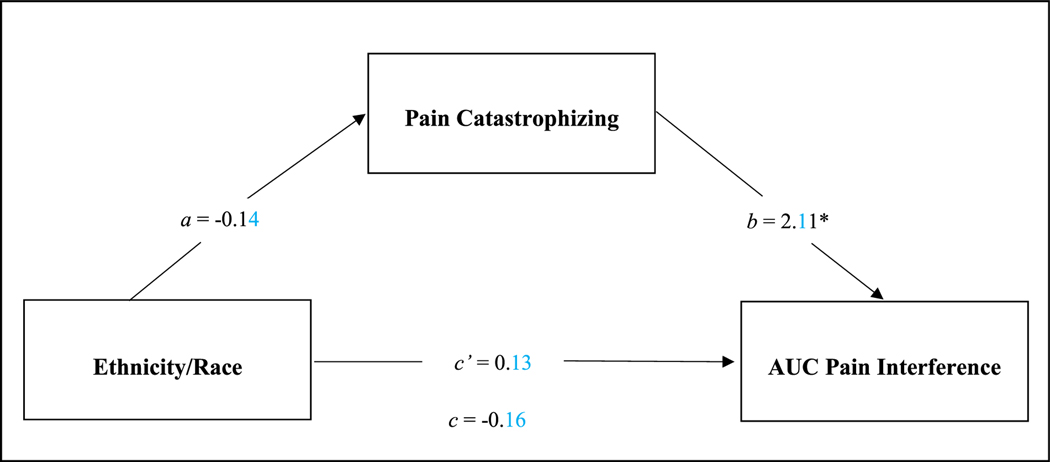

AUC GCPS Pain Interference

Model eight was predictive of significant variance in AUC GCPS pain interference, (R2 = .55, F(9,133) = 18.41, P < .001) (Fig 8). Ethnicity/race was not associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −.717, P = .475, [CI = −.517, .242), however, pain catastrophizing was positively associated with AUC disability, (t = 2.61, P = .010, [CI = .509, 3.720]), suggesting higher pain catastrophizing was predictive of greater pain interference up to two years later. This model showed a non-significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through pain catastrophizing on the AUC GCPS pain interference [95% CI = −1.446, .540].

Figure 8.

Mediation model show pain catastrophizing influences knee pain interference AUC. Note: *P < .05. AUC, area under the curve. Covariates include: study site, age, gender, education, body mass index, income, marital status, and GCPS pain interference.

Supplemental Mediation Analyses

Recognizing that the direction of associations cannot be determined in this cross-sectional study, we also conducted mediational models to consider that greater pain, disability and functional performance may mediate the ethnic/race group differences in pain catastrophizing. The results of these mediation models for ethnicity/race −> pain/disability/functional performance measures −> pain catastrophizing analyses are presented in supplemental Tables S2–S7. Therefore, supplemental mediation analyses were conducted whereby the mediator (pain catastrophizing) and the outcome variables (pain measures: [i.e., SF-MPQ-2, WOMAC Pain, GCPS Pain Intensity]; disability measures: [i.e., WOMAC Physical Function and GCPS interference]; functional performance measure [i.e., SPPB Function Performance]) were reversed such that pain, disability and functional performance variables became the mediator variables and pain catastrophizing became the outcome variable, while the predictor variable (ethnicity/race) remained unchanged. All models controlled for study site, age, gender, education, BMI, income, and marital status.

Ethnicity/Race → SF-MPQ-2 → Catastrophizing

Model one predicted significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .28, F(8,157) = 7.46, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S2). Ethnicity/race was associated with SF-MPQ-2, (t = −3.65, P = <.001, [CI = −1.789, −.532]), indicating higher SF-MPQ-2 among NHB participants, and SF-MPQ-2 was positively associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = 7.04, P <.001, [CI = .198, .352]). This indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through SF-MPQ-2 on pain catastrophizing was statistically significant [95% CI = −.530, −.131].

Ethnicity/Race → WOMAC Pain→ Catastrophizing

Model two accounted for significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .29, F(8,166) = 8.32, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S3). Ethnicity/race was associated with WOMAC pain, (t = −2.15, P = .033, [CI = −2.578, −.111]), indicating higher WOMAC pain among NHB participants, and WOMAC pain was positively associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = 5.55, P < .001, [CI = .073, .153]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through WOMAC pain on pain catastrophizing [95% CI = −.333, −.006].

Ethnicity/Race → WOMAC Physical Function→ Catastrophizing

Model three was predictive of significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .29, F(8,167) = 8.48, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S4). Ethnicity/race was associated with WOMAC physical function, (t = −3.05, P = .003, [CI = −10.416, −2.224]), indicating higher WOMAC physical function among NHB participants, and WOMAC physical function was positively associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = 5.98, P < .001, [CI = .024, .048]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through WOMAC physical function on pain catastrophizing [95% CI = −.443, −.063].

Ethnicity/Race → GCPS Pain Intensity→ Catastrophizing

Model four predicted significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .29, F(8,167) = 8.48, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S5). Ethnicity/race was associated with GCPS Pain intensity, (t = −5.31, P = <.001, [CI = 21.961, −10.051]), indicating higher GCPS Pain intensity among NHB participants, and GCPS Pain intensity positively associated with pain catastrophizing (t = 5.54, P < .001, [CI = .015, .032]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through GCPS Pain intensity on pain catastrophizing [95% CI = −.601, −.182].

Ethnicity/Race → GCPS Interference → Catastrophizing

Model five was predictive of significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .29, F(8,167) = 8.48, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S6). Ethnicity/race was associated with GCPS interference, (t = −2.76, P = .006, [CI = −20.952, −3.489]), indicating higher GCPS interference among NHB participants, and GCPS interference was positively associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = 5.69, P < .001, [CI = .011, .022]). This model showed a statistically significant indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through GCPS interference on pain catastrophizing [95% CI = −.385, −.046].

Ethnicity/Race →SPPB → Catastrophizing

Model six was predictive of significant variance in pain catastrophizing, (R2 = .29, F(8,167) = 8.48, P < .001) (Supplemental Figure S7). Ethnicity/race was not associated with SPPB functional performance, (t = 1.60, P = .111, [CI = −.092, .884]), however, SPPB functional performance was negatively associated with pain catastrophizing, (t = −4.10, P < .001, [CI = −.323, −.113]), indicating lower SPPB functional performance was associated with higher pain catastrophizing. The indirect effect of ethnicity/race, mediated through SPPB functional performance on pain catastrophizing was not statistically significant [95% CI = −.250, .014].

Discussion

Pain catastrophizing has been consistently documented to predict poor pain, disability, and functional outcomes.24,45,49,50,76 Increasing evidence demonstrates that catastrophizing is a significant mediator of race differences in pain.54 However, studies investigating this relationship have primarily examined experimental laboratory-induced pain in healthy pain-free samples.25,26,56,58 Only one study, to date, has investigated the mediating effects of catastrophizing on race differences in chronic pain.59 The current study provides evidence for catastrophizing as a mediator of ethnic/race group differences in OA-related pain, disability, and function. Further, our findings suggest that catastrophizing predicts pain intensity and interference across a 2-year follow-up period similarly in both ethnic/race groups. As expected, we found that compared to NHWs, NHB participants reported higher levels of clinical pain and pain-related disability and demonstrated poorer functional performance. These findings are consistent with prior research54,57,77,86 and these ethnic/racial disparities have been purported to reflect a myriad of structural inequities (e.g., access to health care, perceived racial discrimination) and sociodemographic inequalities (e.g., education, income, occupation) that influence pain and disability.3,29,51,85

In the current study, we found support for catastrophizing as a mediator of ethnic/race group differences in clinical pain, pain-related disability, and functional performance. NHB adults reported greater catastrophizing than NHW adults, though both groups reported low levels of catastrophizing compared to prior studies in clinic-based samples of patients with other chronic pain conditions.65,67 Also, higher catastrophizing was associated with greater pain, disability, and reduced functional performance. Over the 2-year follow-up period, no significant ethnic/race group differences in pain or interference were observed, after controlling for baseline pain and interference. Hence, catastrophizing did not mediate the association of ethnicity/race with pain intensity nor interference over the follow-up period. However, despite the low levels of catastrophizing observed in our sample, catastrophizing significantly predicted pain and pain-related disability over the ensuing two years, even after adjusting for baseline pain and interference. These results provide evidence for the robust predictive power of catastrophizing and its deleterious effects on pain and pain-related outcomes. Additionally, supplementary analyses revealed pain-related outcomes as mediators of ethnic/race group differences and catastrophizing. These findings provide evidence that the relationship between pain and disability and its association with catastrophizing are bidirectional and may be more nuanced and support the contention that catastrophizing is not a characterological trait, but is a more complex phenomenon that can negatively impact pain and disability and catastrophizing can be impacted by pain and disability. While some studies provide evidence that catastrophizing predicts chronic pain outcomes,1,8,44,49,50,71,76 other studies found the opposite predictive relationship, namely that pain was predictive of catastrophizing.31,46,62,89 These disparate findings raise questions regarding whether high pain catastrophizing leads to increases in pain or whether high pain leads to increases in catastrophizing. In an attempt to address this question, a prospective study in 176 subjects investigated changes in pain catastrophizing at baseline and 12 months following total knee replacement.47 The authors found that 71% of subjects with initially high catastrophizing showed significant decreases in catastrophizing following total knee replacement. Therefore, reduction in pain appeared to produce decreased catastrophizing scores, suggesting catastrophizing is a dynamic construct89 and may be a situation-based response to pain.84

While we use the term pain catastrophizing throughout this manuscript, we wish to acknowledge the increasing dissatisfaction with this term among researchers, clinicians and people suffering from chronic pain. Indeed, the term pain catastrophizing seems to be at odds with prevailing patient-centered approaches to research and clinical pain management as the term can be pejorative and stigmatizing. Applying the label “pain catastrophizers” to patients can be a form of patient blaming and stereotyping, which could adversely influence patient-provider shared decision making, thereby adversely impacting the patient’s quality of care.61 Additionally, a recent content analysis of pain catastrophizing items indicated that pain-related worrying and pain-related distress better captured the content of pain catastrophizing measures.17

These concerns about the term pain catastrophizing are amplified in the context of ethnic/racial disparities in pain, because patients from marginalized groups are already at greater risk for marginalization and healthcare experiences that are not patient centered. A previous Institute of Medicine report concluded that patient-related factors such as “patient preferences, care-seeking behaviors, and attitudes are unlikely to be major sources of healthcare disparities”.42 Instead, multiple systemic and provider-level barriers contribute to inadequate healthcare, including substandard pain management in ethnic/racial marginalized groups.42,55,73 The Institute of Medicine published a comprehensive report indicating minorities may experience multiple barriers to access healthcare services “even when insured at the same level as whites”.42 For example, when Black patients access healthcare services they may face provider-related barriers, including provider bias, that influence decisions about pain assessment and pain treatment.3,11,37 Stanton and colleagues79 found that physicians were more likely to underestimate pain in their Black patients compared to their patients of other ethnicities. This is consistent with the findings of Hoffman and colleagues37 that both laypeople and medical trainees endorsed beliefs that biological differences between Blacks and Whites rendered Black individuals less sensitive to pain, and medical trainees who endorsed these beliefs rated the pain of Black patients lower and showed racial bias in their treatment recommendations. Additional research reveals that Blacks are less likely to receive comprehensive assessments and treatment approaches,3,29,52,73 appropriate pain medications,27,82 referral to pain specialists,30 and referral for surgical procedures.81 In addition, providers’ personal bias against marginalized patients’ health behaviors may lead to discrimination73 and stereotyping,11 practices that negatively impact patients’ clinical care. Furthermore, perceived racial discrimination in patients has been associated with feelings of anger and helplessness,9,88 and perceived discrimination is associated with increased psychological stress which may exacerbate chronic pain.10,80

Together, NHB patients’ experiences in the healthcare system and the barriers they face in receiving adequate pain treatment contribute to worst pain outcomes, which could understandably promote negative thinking about their pain and may leave NHB patients to feel that their pain cannot be managed and will continue to worsen. These are the very types of thoughts and feelings that are assessed by pain catastrophizing instruments. Therefore, it is possible that both greater pain severity and higher pain catastrophizing among NHB individuals result from inadequate pain care and suboptimal interactions with a biased healthcare system.

Meaningful progress towards eliminating disparities in pain management will require changes in policy, education, practice, and research.13,53 Therefore, given the complex and long-term nature of interventions to address health disparities at structural/system and provider levels, there is benefit to implementing targeted strategies to intervene at the patient level. Specifically, clinical interventions aimed at reducing pain catastrophizing have been shown to be effective in reducing pain-related outcomes.28,70 Indeed, a pain coping skills intervention designed for patients with high pain catastrophizing who were scheduled for knee arthroplasty was shown to reduce pain, catastrophizing, and disability at 2 month-follow-up.64 Therefore, catastrophizing is a clinically relevant, modifiable construct, and interventions aimed at reducing catastrophizing could have meaningful positive impact on pain outcomes.

Strengths of this study include the recruitment of a large community sample with equal representation of NHB participants. Second, several covariates were included in the analyses in an effort to reduce confounding due to significant differences in sociodemographic factors between the groups. Indeed, low SES has been strongly related to multiple measures of stress and multiple adverse health outcomes. However, the findings should also be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, significant differences in SES between the groups were reported and this could affect pain catastrophizing and pain-outcomes. While we controlled for self-reported education and income, these measures may not adequately account for the multiple components of SES that may influence pain-related outcomes. Second, while pain catastrophizing is highly clinically significant as a construct, limited information exists regarding what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference in pain catastrophizing, and the relatively low levels of catastrophizing in our sample raise further questions regarding clinical significance. Third, the current study used the pain catastrophizing scale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire-revised, which assesses the helplessness domain of pain catastrophizing, rather than a more comprehensive measure of pain catastrophizing such as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale which captures three domains of pain catastrophizing (i.e., magnification, rumination, and helplessness). Fourth, we modified the GCPS instructions and used a limited item set in the quarterly questionnaire, and this modified measure, though similar to the original GCPS, has not been validated. Furthermore, we only assessed knee pain interference with their general activity, so findings may not generalize for other domains of pain-related interference. Finally, robust statistical approaches (e.g., K-nearest-neighbor imputation methods) were used to address missing data in the follow-up dataset, however, data from 35 participants were excluded from the dataset.

In summary, the current study revealed that catastrophizing mediated ethnic/race group differences in pain, disability, and function. NHB adults reported higher catastrophizing than NHW adults and higher levels of catastrophizing was associated with poorer pain, higher rates of disability, and reduced functional performance outcomes. In the 2-year follow-up period, catastrophizing predicted pain and interference across both ethnic/racial groups up to 2 years later. These results point to the need for interventions that target catastrophizing in order to reduce pain-related outcomes in individuals with knee osteoarthritis.

Supplementary Material

Perspective:

The current study examines whether pain catastrophizing mediates the relationship between ethnicity/race and OA-related pain, disability, and functional impairment at baseline and during a 2-year follow-up period in non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White adults with knee pain. These results point to the need for interventions that target pain catastrophizing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Larry Bradley for his invaluable contributions to developing and implementing the UPLOAD Projects.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funding agencies.

Disclosures: Research funding and support provided by NIH/NIA Grants R37AG033906 (RBF) and R01AG054370 (KTS); UF CTSA> Grant UL1TR001427 and UAB CTSA Grant UL1TR001417 from the NIH Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NIH/NINDS K22NS102334, and McKnight Brain Institute Career Development Award (ELT); minority supplement provided to the University of Florida (JSC); NIH/NIAMS K23AR076463-01 (SQB); NIH/NIA Grant R00AG052642 (EJB); and minority supplement supported by the Jacksonville Aging Studies Center (NIH/NIA 3R33AG056540-04S2) (DF).

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.04.018.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P, Pav D, Aloisi R: A dual pathway model of daily stressor effects on rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Behav Med 19:161, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke T, Greenwald R, Hochberg M: Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheumatol 29:1039–1049, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10:1187–1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arango MA, Cano PO: A potential moderating role of stress in the association of disease activity and psychological status among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol Rep 83:147, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badley EM, Wagstaff S, Wood P: Measures of functional ability (disability) in arthritis in relation to impairment of range of joint movement. Ann Rheum Dis 43:563–569, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedson J, Croft PR: The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:116, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW: Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 15:1833–1840, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birch S, Stilling M, Mechlenburg I, Hansen TB: The association between pain catastrophizing, physical function and pain in a cohort of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:421, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broudy R, Brondolo E, Coakley V, Brady N, Cassells A, Tobin JN, Sweeney M: Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. J Behav Med 30:31–43, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown TT, Partanen J, Chuong L, Villaverde V, Griffin AC, Mendelson A: Discrimination hurts: The effect of discrimination on the development of chronic pain. Social Sci Med 204:1–8, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess DJ, Van Ryn M, Crowley-Matoka M, Malat J: Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from dual process models of stereotyping. Pain Med 7:119–134, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell CM, Buenaver LF, Finan P, Bounds SC, Redding M, McCauley L, Robinson M, Edwards RR, Smith MT: Sleep, pain catastrophizing, and central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis patients with and without insomnia. Arthritis Care Res 67:1387–1396, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell LC, Robinson K, Meghani SH, Vallerand A, Schatman M, Sonty N: Challenges and opportunities in pain management disparities research: Implications for clinical practice, advocacy, and policy. J Pain 13:611–619, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caneiro J, O’Sullivan PB, Roos EM, Smith AJ, Choong P, Dowsey M, Hunter DJ, Kemp J, Rodriguez J, Lohmander S: Three Steps to Changing the Narrative about Knee Osteoarthritis Care: A Call to Action. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleveland WS, Grosse E, Shyu WM, Chambers JM, Hastie TJ: Statistical models in S. Local Regression Models; 8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins JE, Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Losina E: Race-and sex-specific incidence rates and predictors of total knee arthroplasty: Seven-year data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthrit Care Res 68:965–973, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crombez G, De Paepe AL, Veirman E, Eccleston C, Verleysen G, Van Ryckeghem DM: Let’s talk about pain catastrophizing measures: An item content analysis. Peer J 8: e8643, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, Suter LG, Losina E: Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: Impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res 68:1743–1750, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieppe P, Cushnaghan J, Tucker M, Browning S, Shepstone L: The Bristol ‘OA500 study’: Progression and impact of the disease after 8 years. Osteoarthr Cartil 8:63–68, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R: Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991–94. J Rheumatol 33:2271–2279, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, Harding G, Coyne KS, Peirce-Sandner S, Bhagwat D, Everton D, Burke LB, Cowan P: Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the short-form mcgill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain 144:35–42, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dworkin SF, von Korff MR, LeResche L: Epidemiologic studies of chronic pain: A dynamic-ecologic perspective. Ann Behav Med 14:3, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards MH, van der Pas S, Denkinger MD, Parsons C, Jameson KA, Schaap L, Zambon S, Castell M-V, Herbolsheimer F, Nasell H: Relationships between physical performance and knee and hip osteoarthritis: findings from the European Project on Osteoarthritis (EPOSA). Age Ageing 43:806–813, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA: Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7:216, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabian LA, McGuire L, Goodin BR, Edwards RR: Ethnicity, catastrophizing, and qualities of the pain experience. Pain Med 12:314–321, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsythe LP, Thorn B, Day M, Shelby G: Race and sex differences in primary appraisals, catastrophizing, and experimental pain outcomes. J Pain 12:563–572, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman J, Kim D, Schneberk T, Bourgois P, Shin M, Celious A, Schriger DL: Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern Med 179:469–476, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson E, Sabo MT: Can pain catastrophizing be changed in surgical patients? A scoping review. Can J Surg 61:311, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC: The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277–294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T: The adequacy of chronic pain management prior to presenting at a tertiary care pain center: the role of patient socio-demographic characteristics. J Pain 11:746–754, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groth-Marnat G, Fletcher A: Influence of neuroticism, catastrophizing, pain duration, and receipt of compensation on short-term response to nerve block treatment for chronic back pain. J Behav Med 23:339–350, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB: A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49:M85–M94, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T: Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 27:1513–1517, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Narasimhan B, Chu G: impute: Imputation for microarray data. Bioinformatics 17:520–525, 2001. 11395428 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes AF: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY, The Guiford Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes AF: Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY, Ebook The Guilford Press. Google Scholar, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN: Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Nat Acad Sci 113:4296–4301, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubertsson J, Petersson IF, Thorstensson CA, Englund M: Risk of sick leave and disability pension in working-age women and men with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72:401–405, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt MA, Birmingham TB, Skarakis-Doyle E, Vandervoort AA: Towards a biopsychosocial framework of osteoarthritis of the knee. Disabil Rehabil 30:54–61, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter DJ, Bierma-zeinstra S: Seminar osteoarthritis. Lancet 393:1745–1759, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter DJ, McDougall JJ, Keefe FJ: The symptoms of osteoarthritis and the genesis of pain. Med Clin N Am 93:83–100, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute of Medicine: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Abbate LM, Callahan LF: Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and caucasians: The johnston county osteoarthritis project. J Rheumatol 34:172–180, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keefe FJ, Brown GK, Wallston KA, Caldwell DS: Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain: Catastrophizing as a maladaptive strategy. Pain 37:51–56, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Egert JR, Affleck G, Sullivan MJ, Caldwell DS: The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain 87:325–334, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovacs FM, Seco J, Royuela A, Corcoll-Reixach J, Pen~aArrebola A, Network SBPR: The prognostic value of catastrophizing for predicting the clinical evolution of low back pain patients: a study in routine clinical practice within the Spanish National Health Service. Spine J 12:545–555, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lape EC, Selzer F, Collins JE, Losina E, Katz JN: Stability of measures of pain catastrophizing and widespread pain following total knee replacement. Arthritis Care Res 72:1096–1103, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawrence J, Bremner J, Bier F: Osteo-arthrosis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis 25:1, 1966 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lazaridou A, Martel MO, Cornelius M, Franceschelli O, Campbell C, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA, Wright JR, Edwards RR: The association between daily physical activity and pain among patients with knee osteoarthritis: The moderating role of pain catastrophizing. Pain Med 20:916–924, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis G, Rice D, McNair P, Kluger M: Predictors of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 114:551–561, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luong M-LN, Cleveland RJ, Nyrop KA, Callahan LF: Social determinants and osteoarthritis outcomes. Aging Health 8:413–437, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meghani SH: Corporatization of pain medicine: implications for widening pain care disparities. Pain Med 12:634–644, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM: Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: Directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med 13:5–28, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meints S, Edwards R: Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 87:168–182, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meints SM, Cortes A, Morais CA, Edwards RR: Racial and ethnic differences in the experience and treatment of noncancer pain. Pain Manag 9:317–334, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meints SM, Hirsh AT: In vivo praying and catastrophizing mediate the race differences in experimental pain sensitivity. J Pain 16:491–497, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meints SM, Miller MM, Hirsh AT: Differences in pain coping between black and white americans: A meta-analysis. J Pain 17:642–653, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meints SM, Stout M, Abplanalp S, Hirsh AT: Pain-related rumination, but not magnification or helplessness, mediates race and sex differences in experimental pain. Journal of Pain 18:332–339, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meints SM, Wang V, Edwards RR: Sex and race differences in pain sensitization among patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain 19:1461–1470, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson AE, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Kraus VB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM: Differences in multijoint radiographic osteoarthritis phenotypes among African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis project. Arthritis Rheumatol 63:3843–3852, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Brien J: Calls to Rename “Pain Catastrophizing”Backed by International Patient-Researcher Partnership. Pain Res Forum, 2020. Available at: https://www.painresearchforum.org/news/150718-calls-rename-%E150712%150780%150719Cpain-catastrophizing%E150712%150780%150719Dbacked-international-patient-researcher-partnership Accessed June10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfingsten M, Hildebrandt J, Leibing E, Franz C, Saur P: Effectiveness of a multimodal treatment program for chronic low-back pain. Pain 73:77–85, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR: Pain catastrophizing: A critical review. Expert Rev Neurotherapeut 9:745–758, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riddle DL, Keefe FJ, Nay WT, McKee D, Attarian DE, Jensen MP: Pain coping skills training for patients with elevated pain catastrophizing who are scheduled for knee arthroplasty: A quasi-experimental study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 92:859–865, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riley JL III, Robinson ME: CSQ: Five factors or fiction? Clin J Pain 13:156, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson ME, Riley JL 3rd, Myers CD, Sadler IJ, Kvaal SA, Geisser ME, Keefe FJ: The Coping Strategies Questionnaire: A large sample, item level factor analysis. Clin J Pain 13:43–49, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ: The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: Relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain 17:33–44, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roux CH, Saraux A, Mazieres B, Pouchot J, Morvan J, Fautrel B, Testa J, Fardellone P, Rat AC, Coste J: Screening for hip and knee osteoarthritis in the general population: Predictive value of a questionnaire and prevalence estimates. Ann Rheum Dis 67:1406–1411, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruehlman LS, Karoly P, Newton C: Comparing the experiential and psychosocial dimensions of chronic pain in African Americans and Caucasians: Findings from a national community sample. Pain Med 6:49–60, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schutze R, Rees C, Smith A, Slater H, Campbell JM, O’Sullivan P: How can we best reduce pain catastrophizing in adults with chronic noncancer pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 19:233–256, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Severeijns R, Vlaeyen JWS, van den Hout MA, Weber WEJ: Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clin J Pain 17:165–172, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharif B, Garner R, Sanmartin C, Flanagan WM, Hennessy D, Marshall DA: Risk of work loss due to illness or disability in patients with osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology 55:861–868, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB: Race, ethnicity, and pain among the US adult population. J Health Care Poo Underserv 21:177–220, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shelby RA, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, Dixon KE, Blumenthal JA: Domain specific self-efficacy mediates the impact of pain catastrophizing on pain and disability in overweight and obese osteoarthritis patients. J Pain 9:912–919, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Showery JE, Kusnezov NA, Dunn JC, Bader JO, Belmont PJ Jr, Waterman BR: The rising incidence of degenerative and posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee in the United States military. J Arthroplasty 31:2108–2114, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, Dixon KE, Waters SJ, Riordan PA, Blumenthal JA, McKee DC, LaCaille L, Tucker JM: Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in osteoarthritis patients: relationships to pain and disability. J Pain Symptom Manage 37:863–872, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song J, Chang HJ, Tirodkar M, Chang RW, Manheim LM, Dunlop DD: Racial/ethnic differences in activities of daily living disability in older adults with arthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res 57:1058–1066, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD: Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Care Res 55:248–255, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Staton LJ, Panda M, Chen I, Genao I, Kurz J, Pasanen M, Mechaber AJ, Menon M, O’Rorke J, Wood J: When race matters: Disagreement in pain perception between patients and their physicians in primary care. J Nat Med Assoc 99:532, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Terry EL, Fullwood MD, Booker SQ, Cardoso JS, Sibille KT, Glover TL, Thompson KA, Addison AS, Goodin BR, Staud R: Everyday discrimination in adults with knee pain: The role of perceived stress and pain catastrophizing. J Pain Res 13:883, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thirukumaran CP, Cai X, Glance LG, Kim Y, Ricciardi BF, Fiscella KA, Li Y: Geographic variation and disparities in total joint replacement use for medicare beneficiaries: 2009 to 2017. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:2120–2128, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, Goe L: Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med 35:11–16, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, Bjo€rk J, Hawker G, Dahlberg LE, Lohmander LS, Englund M: Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: A population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoarthr Cartil 22:1826–1832, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turner JA, Aaron LA: Pain-related catastrophizing: What is it? Clin J Pain 17:65–71, 2001. 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Editors Understanding Co, Racial E, Care EDiH, Stith AY, Smedley BD, Nelson AAR: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vaughn IA, Terry EL, Bartley EJ, Schaefer N, Fillingim RB: Racial-ethnic differences in osteoarthritis pain and disability: A meta-analysis. J Pain 20:629–644, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vina E, Ran D, Ashbeck E, Kwoh C: Natural history of pain and disability among African−Americans and Whites with or at risk for knee osteoarthritis: A longitudinal study. Osteoarthr Cartil 26:471–479, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vines AI, Baird DD, McNeilly M, Hertz-Picciotto I, Light KC, Stevens J: Social correlates of the chronic stress of perceived racism among Black women. Ethn Dis 16:101, 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wade JB, Riddle DL, Thacker LR: Is pain catastrophizing a stable trait or dynamic state in patients scheduled for knee arthroplasty? Clin J Pain 28:122–128, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walker JL, Harrison TC, Brown A, Thorpe RJ Jr., Szanton SL: Factors associated with disability among middle-aged and older African American women with osteoarthritis. Disabil Health J 9:510–517, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wallace IJ, Worthington S, Felson DT, Jurmain RD, Wren KT, Maijanen H, Woods RJ, Lieberman DE: Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Nat Acad Sci 114:9332–9336, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.