Abstract

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a systemic connective tissue disorder that is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance. While clinically this disease manifests in many different ways, the most life-threatening manifestations are related to cardiovascular complications including mitral valve prolapse, aortic insufficiency, dilatation of the aortic root, and aortic dissection. In the past 30 years, research efforts have not only identified the genetic locus responsible but have begun to elucidate the molecular pathogenesis underlying this disorder, allowing for the development of seemingly rational therapeutic strategies for treating affected individuals. In spite of these advancements, the cardiovascular complications still remain as the most life-threatening clinical manifestations. The present chapter will focus on the pathophysiology and clinical treatment of Marfan syndrome, providing an updated overview of the recent advancements in molecular genetics research and clinical trials, with an emphasis on how this information can focus future efforts toward finding betters ways to detect, diagnose, and treat this devastating condition.

Keywords: Aorta, aneurysm, extracellular matrix, collagen, metalloproteinase, thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection syndrome, Marfan syndrome (MFS), Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), endoglin, mitral valve, SMAD, TGF-β receptor, mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal related kinase (ERK), fibrillin, genetic testing, losartan, valvulopathy, Ghent nosology, β-blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), Fbn1C1039G/+, mgR/mgR

1.0. Introduction

1.1. History and overview

Approximately 125 years ago (1896), French pediatrician Antoine Bernard-Jean Marfan published a case report describing a 5½-year-old girl (Gabrielle P.) with extraordinary musculoskeletal abnormalities that included severe scoliosis and fibrous contractures of the fingers, in the absence of ocular and cardiac abnormalities (75). While much later (1971), it was suggested that Gabrielle may have actually had Congenital Contractural Arachnodactyly (CCA) in place of MFS, based on current diagnostic criteria (9). Nonetheless, this early observation laid the foundation for the description of a genetic syndrome that has come to be known as Marfan Syndrome (MFS; OMIM #154700). Interestingly, the first description of this disorder was likely made 20-years earlier by E. Williams, an Ophthalmologist from Cincinnati, OH. Williams published a case report in the Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society, describing a brother-sister pair with ectopia lentis who both were extraordinarily tall and “loose-jointed” from birth (107). It has been suggested that his keen observation went largely unnoticed because he did not practice at an academic center. Since that time, key discoveries have added to the symptomology and clinical description of this multisystem connective tissue disorder, providing better discrimination between similar heritable conditions. It wasn’t until 1914 that Boerger, officially added ectopia lentis to the growing list of other MFS-related symptoms (12). The first cardiovascular manifestations were described by Salle in 1912. He reported the results of a necropsy following the death of a 2½ month old infant diagnosed with MFS, that displayed “striking changes in the mitral valve” (97). A literature review written by Rados in 1942, supported this early observation by Salle, describing the presence and prevalence of mitral valve regurgitation (“click-murmur syndrome”) in the MFS patient population (91). The first descriptions of aortic aneurysm and dissection were recorded in 1943 by Etter and Glover (35), and Baer and colleagues (8). This was followed by key advancements in 1955 by Victor McKusick, defining the heritable nature of MFS and its sequelae, along with the new cardiovascular aspects, including aortic root dilatation and aortic regurgitation (76, 77). Subsequently, this was followed by a postmortem study completed by Goyette and Palmer in 1963, in which they confirmed that evidence of cystic medial necrosis in the ascending aortic aneurysm, aortic insufficiency, and aortic dissection were prevalent in MFS patients (49). In 1975, Brown and coworkers reported the first study examining MFS-related cardiovascular manifestations using cardiac ultrasound to record noninvasive quantitation of aortic size and mitral valve function (14). This pushed the limits of echocardiographic studies during a time when standardized criteria for measuring the aortic root had yet to be established, resulting in a wide “normal” range, suggesting that mild aortic root dilatation may have gone undiagnosed in many MFS patients, particularly children. It wasn’t until the early 1990’s that the genetic locus responsible for MFS was identified (29, 31, 33). Work by Dietz and Pyeritz localized key mutations to the gene encoding a large extracellular matrix structural protein, called fibrillin-1 (FBN1) (32). For more than a century, many dedicated geneticists, physicians, and scientists have contributed toward understanding the mechanistic and clinical pathogenesis of this multisystem connective tissue disorder. We now know that MFS is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with variable penetrance, affecting 1 in 3–5,000 people without preference for ethnicity or geographic location (90). This connective tissue disorder affects multiple organ systems including the skeletal, pulmonary, ocular, central nervous, and cardiovascular systems of the body (22, 90).

1.2. Identification of the primary genetic defect

The primary gene defect in MFS lies on chromosome 15q21.1, within the coding region of the fibrillin-1 gene (FBN1) (30). Fibrillin-1 is a large 350 kDa glycoprotein, produced and secreted by fibroblasts, and incorporated into the extracellular matrix (ECM) as insoluble microfibrils (68). These microfibrils serve as a scaffold for the deposition of elastin and are necessary to build proper elastic architecture to provide elasticity to dynamic connective tissues (67). Structurally, each Fibrillin-1 monomer contains multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like motifs that are arranged in tandem orientation. There is a total of 47 EGF-like motifs in all, 43 of which contain specialized calcium binding sequences, termed calcium-binding EGF (cbEGF) repeats (111). These cbEGF modules sequester extracellular calcium in order to protect against fibrillin proteolysis, promote interactions between fibrillin monomers and other cellular components such as the integrins (e.g. αvβ3), and serve to stabilize the structure of the microfibrils, which favors lateral packing (92, 93). The tandem arrays of cbEGF motifs (1 to 12 repeats) are separated by seven 8-cys/TB modules. These modules have high homology to the latent transforming growth factor binding proteins (LTBPs), and are characterized by eight highly conserved cysteine residues, including a unique cysteine triplet (92, 111). Fibrillin monomers self-assemble into macroaggregates that form the basic structure on which mature elastin fibers are synthesized from tropoelastin subunits. Accordingly, it was originally hypothesized that mutations in fibrillin-1 resulted in weak and disordered elastic fiber formation, causing a disruption of the microfibril network connections to the adjacent interstitial cells (89). In the aorta, it was suggested that this gave rise to a weakened vascular wall, prone to dilation and dissection; commonly observed in patients with MFS.

Contrary to the “weakened constitution” hypothesis, Dietz and colleagues suggested that MFS syndrome is caused by more than just a disordered microfibril matrix (30). In addition to directing elastogenesis and providing structural integrity to the elastic lamellae, the 8-cys/TB domains of fibrillin are involved in the sequestration of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). TGF-β is synthesized as a pre-pro-polypeptide that is cleaved in a post-Golgi compartment to yield a mature growth factor molecule complexed with an inactive cleavage fragment, termed the latency-associated peptide (LAP). Homodimers of the mature TGF-β and the LAP then uniquely combine and form a tight biologically inactive complex called the small latent complex (SLC). The SLC covalently binds to LTBP by forming disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in the LAP and a cysteine rich motif in the LTBP (5, 18, 93). This large latent complex (LLC) is then secreted from the cell and functions to target latent-TGF-β to the ECM, specifically to fibrillin microfibrils, and the 8-cys/TB motifs they contain (17, 59). This complex sequestration process serves a dual role in the regulation of TGF-β signaling. First, the LAP sequesters active TGF-β, rendering it inactive, preventing unregulated stimulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Second, interactions of the LLC with microfibrillar proteins, localizes and concentrates the inactive latent TGF-β at critical signaling sites within the ECM, making it available for rapid release and activation when required by the cell. As a result, when Dietz and coworkers localized multiple mutations within the FBN1 gene to sites that were associated with sequestering the LLC (32), they hypothesized that fibrillin-1-dependent abnormalities observed in MFS may lead to impaired sequestration of latent TGF-β complexes and enhanced TGF-β signaling (30).

In support of the Dietz hypothesis, evidence reported by Isogai and coworkers, demonstrated that fibrillin-1 and LTBP-1 were directly associated in vivo, and that the interaction was mediated by the cbEGF domains common to both proteins (59). Chaudhry and coworkers identified a peptide of fibrillin-1 (encoded in exons 44–49) that was capable disrupting the interaction between fibrillin-1 and the C-terminal domain of LTBP-1 (18). They demonstrated that the release of the LLC led to enhanced TGF-β signaling as determined by the phosphorylation Smad-2. While their work defined a physiological mechanism by which the LLC could be released from fibrillin-1, it did not address how TGF-β was released from the SLC. Studies by Ge et al. demonstrated that bone morphogenetic protein 1 (BMP1)-like metalloproteinases were capable of hydrolyzing LTBP-1 at two independent sites (44). This resulted in the release of the SLC and subsequent activation of TGF-β via further cleavage of the LAP by non-BMP1-like proteinases. In similar fashion, work by Tatti ei al. demonstrated that LTBP-1 could be hydrolyzed by the action of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase (103). These studies suggested that proteolysis of LTBP-1 was sufficient to release the SLC, which was then subsequently acted upon by other extracellular proteases to release active TGF-β in a non-regulated fashion. In addition to proteolysis of the SLC, a number of other mechanisms have been shown to catalyze the release TGF-β or modify its association with the LAP by rendering it active; these include non-proteolytic dissociation by interaction with thrombospondin or integrin αvβ6, and release from the LAP by exposure to acidic or oxidative stress (reviewed in (5)).

Taken together, the missense mutations identified in the FBN1 gene, have been shown to alter the interaction between FBN1 and the TGF-β-LLC, resulting in aberrant sequestration of latent TGF-β. Upon further proteolytic action, LTBP releases the bound SLC, which subsequently releases activated homodimers of TGF-β that are capable of binding and activating the TGF-β signaling pathway. As a result of these biochemical studies, many of the clinical manifestations of MFS were looked at in a new light, focusing on how a weakened fibrillar elastic matrix could be exacerbated by enhanced TGF-β signaling.

2.0. Diagnosis and Clinical Presentation

2.1. Diagnostic Criteria

Diagnosis over the years often relied heavily on the treating physician to recognize the evidence of multiple clinical features scattered across multiple organ systems. Although these common clinical features do indeed appear in most patients, the variable penetrance of the genetic defect lead to inconsistencies in the time of onset, sometimes making a definitive diagnosis difficult. To improve diagnostic ability, an international clinical congress met in 1986 to formalize and categorized the common clinical diagnostic criteria; these criteria were thus termed the Berlin nosology (10). Over time weaknesses were discovered in these criteria, which were further illuminated by the addition of novel molecular testing. As a result, the criteria were revised to include requirements for diagnosis of a first degree relative, skeletal involvement in 4 of 8 typical skeletal manifestations, any potential contribution from molecular diagnostics, and delineation of criteria for other heritable conditions with partial overlapping phenotypes (28). This set of diagnostic standards became known as the revised Ghent nosology. As information continues to be gathered about disease presentation, other heritable connective tissue disorders, and advanced molecular diagnostics, our capacity to discriminate similar but genetically and phenotypically unique diseases away from MFS has improved. The most recent iteration of the diagnostic criteria is known as the 2010 Ghent nosology (Table 1). This version of the diagnostic criteria rely heavily on the presence of aortic root aneurysm, ectopia lentis, family history, and genetics, but still requires a combination of two major criteria in different body systems, plus a minor criterion in a third body system. Furthermore, the 2010 Ghent nosology have advanced our ability to distinguish MFS from other heritable conditions, potentially avoiding unnecessary diagnostic testing, anxiety, and medical interventions. While the diagnosis of MFS in a patient that had a first degree relative who had previously been diagnosed with MFS was quite simple, patients lacking an affected first degree relative remain a bit more challenging. To facilitate the often-complex diagnostic process, a scoring system was developed (Table 2) (73). Accordingly, the presence of an aortic root aneurysm, ectopia lentis, or a systemic score ≥7 provides sufficient confidence to make a positive diagnosis.

Table 1. Revised Ghent Criteria for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome (MFS) and related conditions in the absence of family history of Marfan syndrome.

(Adapted from Loeys, B.L. et al.; J Med Genet 47: 476–485, 2010) MASS: myopia, mitral valve prolapse, borderline aortic root dilation, striae, skeletal findings phenotype; MVPS: mitral valve prolapse syndrome; Note: 1) aortic root z-score calculators for pediatric and adult populations can be found at www.marfan.org; 2) the presence of an aortic dissection can supplant a Z-Score cutoff for diagnosis of MFS.

| Aortic Root Dimension | Presence of Ectopia Lentis | Genetic Testing | Systemic Score | Other Considerations | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Aortic Dimensions | |||||

| Z-Score ≥ 2 | + | - | n/a | MFS | |

| Z-Score ≥ 2 | Causal FBN1 mutation | n/a | MFS | ||

| Z-Score ≥ 2 | - | ≥7 | MFS | ||

| Normal Aortic Dimensions | |||||

| Z-score < 2 | + | Causal FBN1 mutation | n/a | MFS | |

| Z-score < 2 | + | Non-MFS FBN1 mutation OR no FBN1 mutation | n/a | Ectopia Lentis Syndrome | |

| Z-score < 2 | No | - | ≥ 5 | MASS | |

| Z-score < 2 | No | - | < 5 | Mitral Valve Prolapse | MVPS |

Table 2. Marfan Syndrome Diagnostic Scoring System.

(Adapted from Loeys, B.L. et al.; J Med Genet 47: 476–485, 2010). US/LS: Upper segment/lower segment ratio, score ≥7 indicates systemic involvement.

| Features | Points |

|---|---|

| • Wrist AND thumb sign / Wrist OR thumb sign | 3 / 1 |

| • Pectus carinatum deformity / Pectus excavatum or chest asymmetry | 2 / 1 |

| • Hindfoot deformity / Plain pes planus | 2 / 1 |

| • Pneumothorax | 2 |

| • Dural ectasia | 2 |

| • Protrusio acetabuli | 2 |

| • Reduced US/LS AND increased arm/height AND no severe scoliosis | 1 |

| • Scoliosis or thoracolumbar kyphosis | 1 |

| • Reduced elbow extension | 1 |

| • Facial features (3/5 required: dolichocephaly, enophthalmos, down slanting palpebral fissures, malar hypoplasia, retrognathia) | 1 |

| • Skin striae | 1 |

| • Myopia> 3 diopters | 1 |

| • Mitral valve prolapse (all types) | 1 |

| Maximum | 20 |

2.2. Clinical Presentation of MFS

Marfan syndrome, without appropriate and timely treatment, leads to a reduced lifespan with death usually in the third to fifth decades of life (47). With appropriate medical and surgical care, however, patients can expect a lifespan approaching normal. Early diagnosis, expectant management, and multidisciplinary expertise throughout the patient’s lifetime are key to achieving a near normal quantity of life for people with Marfan syndrome. Even so, there are significant detriments to quality of life based on repeat hospitalizations, a lifetime of medical and surgical therapies, as well as pain and disability from the musculoskeletal, ocular, neurologic, pulmonary, and cardiovascular sequelae (47).

2.2.1. Musculoskeletal Manifestations

Musculoskeletal abnormalities are often the first finding that raises suspicion for MFS. The classic MFS phenotype includes exaggerated long bone growth accompanied by scoliosis, pectus deformities, and increased joint laxity. Aberrant TGF-β signaling, as a result of mutations in FBN1 during bone growth and mineralization, has been implicated in MFS-related osteoporosis and long bone overgrowth (85). Dysregulated osteogenesis and osteoclastic activity lead to excessive growth in both long bones and the axial skeleton. Excessive rib length leads to anterior or posterior displacement of the sternum, causing pectus deformities. Dysregulated skeletal growth leads to other common musculoskeletal findings in MFS, including increased arm span, pes planus, wrist sign, and the thumb sign. Patients with MFS also display a higher fracture rate, presumably due to osteopenia combined with joint instability and deformities that worsen with age (105). Scoliosis in MFS patients is quite common and can be both disabling and painful. Surgical repair of spinal alignment deformities, however, carries a higher risk for complications when compared to unaffected patients (69). While it is commonly held that MFS patients are tall and slender, this is not always true. Abnormal height should be evaluated relative to unaffected family members. Additionally, obesity and MFS can co-exist, which can serve to exacerbate joint and spinal deformities, and should likewise be carefully managed.

2.2.2. Ocular and Craniofacial Manifestations

Visual disturbances are common in Marfan syndrome, related both to abnormal globe morphology and to laxity in the support structures of the lens and retina. The globe can be elongated with a flatter, thinner cornea, often showing posterior displacement within the orbit due to changes in the orbit volume (called endophthalmos), along with an increased distance between the eyes (hypertelorism) (19). One of the most common manifestations associated with MFS, and possibly the first identified, was thought to be caused by weakened structural filaments in the lens of the eye, likely due to the presence of mutated fibrillin-1 protein. This predisposed patients to ectopia lentis, a dislocation or displacement of the natural crystalline lens outside of the hyaloid fossa, free-floating in the vitreous, present in the anterior chamber, or lying directly on the retina (20). Around 30% of MFS patients will develop ectopia lentis, which is rarely seen outside of this disorder, but can result from facial trauma (16, 45). Ectopia lentis is one of the cardinal features in the 2010 Ghent nosology. Myopia and astigmatism are also quite common and can be easily corrected with lenses. Retinal detachment occurs in about 15% of MFS patients (16). Both ectopia lentis and retinal detachment may require ophthalmologic surgery to preserve vision. The majority of ophthalmologic problems manifest before age 30, and close follow up with an ophthalmologist starting in early childhood is recommended. Additional craniofacial findings may include a condition where the head is longer relative to its width (called dolichocephaly), down slanting palpebral fissures of the eye, malocclusion of the maxilla or mandible (retrognathia), a high arched palate, and underdevelopment of the upper jaw (malar hypoplasia)

2.2.3. Neurologic Manifestations

Dural Ectasia is dilation of the neural canal, usually in the lumbosacral region of the spinal cord. Though it can be found in a number of other connective tissue disorders, the presence of dural ectasia is another cardinal feature in the 2010 Ghent Nosology. It is commonly associated with MFS and found in more than 80% of patients with a prior diagnosis (74). The dilation may lead to thinning of the cortex of the vertebral bodies and pedicles, and enlargement of the neural foramina, or anterior meningocele (28). These changes often lead to chronic back pain (2), or to postural headaches related to intracranial hypotension.

2.2.4. Pulmonary Manifestations

Spontaneous pneumothorax is the chief pulmonary manifestation of Marfan syndrome, and blebs are commonly seen on radiographic imaging (19, 83). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) can occur secondary to a weakened trachea (tracheomalacia), and has been associated with increased TGF-β signaling in the lung of MFS patients. Upper airway obstruction and obstructive sleep apnea related to abnormal oropharyngeal anatomy can also occur. Restrictive lung disease can be exacerbated in the setting of severe kyphosis or pectus excavatum, often associated with MFS.

2.2.5. Cutaneous findings

Stretch marks on the skin (striae atrophicae) may occur in anyone as a result of rapid growth adolescence and pregnancy or with marked weight gain or loss. Patients with MFS, however, are prone to develop stretch marks, often at an early age and without weight change (50). These striae, frequently seen on the trunks of MFS patients, tend to appear in near body parts subject to stress, such as the shoulders, hips, and lower back.

2.2.6. Cardiovascular Manifestations

Cardiovascular disease is the primary determinant of lifespan in MFS patients (106). The phenotype varies widely by age of presentation and severity of disease. The spectrum of MFS-related cardiovascular disease includes aneurysmal dilation of the aortic root, and proximal pulmonary arteries, thoracic aortic dissection and aneurysm, mitral and tricuspid valve prolapse, cardiomyopathy, and supraventricular arrhythmias (38, 102). Of these, aortic aneurysm and dissection are the most immediately life-threatening (52). In the early 1970’s, the outcomes of emergent surgical repair of the aortic valve and root in MFS patients were unacceptably poor. With the development of the Bentall procedure (11), which was first performed on a patient with MFS, outcomes were dramatically improved and use of the composite graft (Bentall) procedure, rapidly became the international standard (48). Mortality related to prophylactic root replacement has proven to be safe and effective in MFS patients (1), and represents the single most effective intervention leading to a longer life span. In many cases, a valve-sparing procedure can be performed, which negates the need for long term anticoagulation and further improves long-term survival.

The classic aortic aneurysm associated with MFS is described as “annulo-aortic ectasia,” highlighting the fact that both the aortic annulus and the sinuses of Valsalva are dilated. Uncorrected, this can lead to aortic insufficiency, aortic dissection, and congestive heart failure. In most instances, the ascending aorta and arch retain their normal dimensions, leading to an “Erlenmeyer flask” shaped aneurysm originating at the aortic valve annulus. As the aorta dilates, the risk for aortic rupture and dissection increases. Population studies have suggested that MFS patients are approximately 200 times more likely to die from aortic disease (52), and that half of patients <40 years old who suffer from aortic dissection likely have MFS (27). It is unclear why the sinuses of Valsalva are more prone to early dilation than other aortic segments. However, recent biomechanical studies have demonstrated that aortic tissue from MFS patients demonstrated increased sinus stiffness with medial degeneration, both during aging and with aneurysmal growth (109). This suggests that the increased aortic stiffness present in in the aortic root, may significantly contribute to dilation and dissection early in disease pathogenesis. It is important to note, as MFS patients are now routinely surviving beyond their 30’s following prophylactic aortic root repair, aortic dissection involving the aortic arch and/or descending thoracic aorta are becoming more common. Moreover, these patients experience elevated risk of thoracoabdominal aneurysms and dissections, as well as peripheral artery aneurysms (110). Reports of the presence of myocardial fibrosis leading to distinct non-ischemic cardiomyopathy independent of valvular lesions, as well as an increased propensity for supraventricular tachycardias have also emerged, presumably due to the role of fibrillin-1 in maintaining normal structure and function of the myocardium (21, 63, 100). In teens and young adults, aortic valve regurgitation and aortic root disease become the dominant cardiac pathologies, however mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation are also commonly encountered.

Cardiovascular manifestations in neonates are less common, however with particularly aggressive forms of the MFS, they are affected by severe mitral and tricuspid valvular regurgitation, often leading to cardiac failure and death. This phenotype has commonly been called “Neonatal Marfan Syndrome” though some have suggested this term be retired in favor of “Early Onset Marfan Syndrome” or “Rapidly Progressive Marfan Syndrome” (56, 110). Fortunately, aortic dissection in the pediatric MFS patient population remains rare.

Mitral valve dysfunction was the earliest cardiovascular manifestation of MFS syndrome identified (97) and represents a key cardinal feature of the 2010 Ghent nosology. Myxomatous thickening and elongation of the mitral valve leaflets commonly occur in MFS patients in response to mutations in FBN1 (64). Prolapse of the anterior leaflet, or bileaflet prolapse, are more common in MFS than in the degenerative mitral valve regurgitation populations.

All patients with suspected or confirmed MFS should be followed by a cardiologist appropriate for the age group and diagnosis. Ideally, these patients should also be referred for genetic counseling, and have close access to a tertiary cardiovascular surgery program with experience in valve sparing aortic root operations, mitral valve repair, and thoracoabdominal aortic interventions.

3.0. Molecular Pathogenesis

3.1. Mouse models of MFS

To enhance the ability to study the pathogenesis of MFS, small animal models designed to recapitulate the clinical phenotypes observed in MFS patients, were developed. Three primary strains emerged and have now been used for more than two decades to define mechanisms and disease sequalae. The first strain developed by Periera et al., designed to replicate the dominant-negative effects of fibrillin-1 mutations in MFS, targeted exons 19–24 for replacement with a neomycin resistant expression cassette (88). The resulting mouse (designated Fbn1mgΔ/mgΔ) resulted in a substantial reduction in fibrillin-1 protein (almost complete) but retained normal elastin levels. There was no fetal loss of transgenic pups, and no overt phenotypic abnormalities at birth. At approximately 3-weeks after birth however, they would all suddenly die from cardiovascular complications, showing evidence of hemothorax and large vessel catastrophe upon necropsy. The mgΔ/+ heterozygotes, on the other hand, were morphologically and histologically indistinguishable from wild-type animals, living a normal lifespan with normal fertility. The second MFS strain generated, was also developed by Periera et al., using the same targeting vector and scheme as the Fbn1mgΔ/mgΔ mouse. This strain, designated Fbn1mgR/mgR, was the result of an aberrant recombination event that only replaced exons 20–24, retaining exon 19 (89). Similar to the original strain, the Fbn1mgR/mgR were born with reduced fibrillin-1 protein levels. They contained on average, approximately 25% of the normal amount of fibrillin-1, with variability depending on secondary factors, which suggested there may be a minimum threshold, that once reached would be lethal embryologically. Importantly, the Fbn1mgR/mgR mice displayed classic MFS phenotypic features in the skeleton including progressive kyphosis, overgrowth of the ribs, and elongation of the long bones. The most severe manifestations were displayed in the cardiovascular system and included aortic aneurysm and dissection. The homozygous mgR mice typically survived to 3.8 months on average before dying (89). Once again, the heterozygous mgR/+ mice were indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates. The third MFS mouse strain developed was based on a common missense mutation identified in the human MFS patient population (62). In this strain, mice heterozygous for a C to G cysteine substitution in a calcium binding EGF-like domain (designated Fbn1C1039G/+), resulted in a 50% reduction in fibrillin-1 protein at birth, and recapitulated many of the human MFS phenotypic features including the pulmonary, skeletal, and cardiovascular manifestations. Mice homozygous for the Fbn1C1039G mutation uniformly died in the perinatal period from aortic catastrophe. While a small number of other MFS mouse strains exist, these three strains were the primary tools utilized to define much of the molecular pathogenesis of MFS. These animals replicated clinical MFS features to different degrees, based on the severity of fibrillin-1 loss, and formed the basis for several key discoveries, as well as serving as a testbed for translational studies that ultimately resulted in novel clinical trials.

3.2. Identification of disease mechanisms

Several key laboratory studies were initiated to provide empirical support for the role of aberrant TGF-β signaling in the pathogenesis of MFS. First, Neptune and coworkers described that the lung abnormalities, evident in the immediate postnatal period in fibrillin-1 deficient mice (Fbn1mgΔ/mgΔ), were related to enhanced TGF-β activation and signaling, and that the perinatal administration of a TGF-β neutralizing antibody could rescue the defect in alveolar septation (82). The second study used mice carrying a hypomorphic allele of the fibrillin-1 missense mutation (Fbn1C1039G/+) that effectively recapitulated most of the MFS clinical phenotypes. In this study, Ng and coworkers similarly demonstrated that treatment with a TGF-β neutralizing antibody was able to reverse myxomatous changes in the mitral valve, rescuing the prolapse defect (84). This was followed with a study by Habashi et al., using the same Fbn1C1039G/+ mouse, which demonstrated that the treatment with the TGF-β neutralizing antibody was sufficient to attenuate the spontaneous aortic root dilatation, elastic fiber fragmentation, and activation of downstream TGF-β signaling intermediates (phospho-Smad2) (54).

The use of β-blockers as a first line therapy for MFS patients was considered standard of care and offered to all patients with aortic root dilatation. As a class, β-blockers (e.g. atenolol) functioned by regulating systemic blood pressure as well as the cardiac pulse wave (dP/dt; rate-rise time). The underlying premise was that attenuation of the force of the cardiac pulse wave as it moved through the aorta, would decrease in systemic blood pressure and aortic wall tension and thereby must be advantageous towards the prevention of aneurysm rupture and continued root dilatation. With this in mind, Habashi and coworkers tried another class antihypertensives; the angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs), specifically losartan (54). There were several reasons supporting the use losartan in models of MFS. First, Daugherty et al., discovered that treatment with an Ang-II type-I specific receptor (AT1R) blocker (losartan) could attenuate AngII-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation, while treatment with an Ang-II type-II specific receptor (AT2R) inhibitor (PD123319) enhanced aortic pathology and aneurysm development. This suggested that activation of the AT1R pathway had deleterious effects on aneurysm development, while signaling through the AT2R pathway may have protective effects. Similarly, this drove the argument that AT1R selective antagonism may be better than the combined antagonism achieved with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (24). Secondly, many studies had previously demonstrated that losartan could attenuate TGF-β signaling by inhibiting AngII-dependent expression of TGF-β ligands and receptors (36, 42, 81, 108). These important discoveries led Habashi et al. to hypothesize that treating MFS mice with losartan may be advantageous both for its ability to lower systemic blood pressure and its ability to attenuate TGF-β signaling. Indeed, treating MFS mice (Fbn1C1039G/+) with losartan attenuated aortic root dilatation, similar to treatment with the TGF-β neutralizing antibody (54). These results indirectly implicated enhanced TGF-β signaling as the primary mechanism underlying FBN1 mutations. Subsequent studies by Carta et al. (15) and Rodriguez-Vita and coworkers (94), demonstrated that AngII could stimulate the phosphorylation of Smad-2, independent of signaling through the type-I TGF-β receptor (ALK-5), resulting in enhanced production of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). Importantly, losartan treatment was able to attenuate both the phosphorylation of Smad-2 and the accumulation of CTGF, suggesting a role for an as yet unknown downstream mediator in the AT1R pathway. Interestingly, AngII stimulation of Smad-2 phosphorylation was attenuated by treatment with a p38 MAPK selective inhibitor (SB203580), suggesting that AngII induced Smad-2 phosphorylation by a non-canonical pathway involving p38 MAPK that was independent of TGF-β receptor signaling (15). The importance of non-canonical TGF-β signaling in MFS has gained further support by a subsequent series of studies by Habashi (53) and Holm (58) demonstrating that both ERK1/2 and JNK1 could be activated by AngII, and inhibition of either pathway could attenuate aortic disease in MFS mice (Fbn1C1039G/+).

4.0. Genetic Testing and Patient Management

The classic ocular, skeletal, neurologic, and cardiovascular manifestations result from a combination of both fibrillin-1 structural weakness and abnormal TGF-β signaling, which leads to pleiomorphic changes depending on the local environment and the stage of tissue development. In fact, this deeper understanding of the role of TGF-β signaling has led to the appropriate delineation of similar but genetically unique inherited vascular connective disorders. The most notable of these, Loeys-Dietz Syndrome, is caused by an inherited defect in the TGF-β receptors and has a phenotype that is distinct from but commonly identified as MFS. To assist in the differentiation of heritable connective tissue disorders that have overlapping symptomology, genetic testing has taken on a larger role, and has been included as part of the criteria defined in the 2010 Ghent nosology.

4.1. Genetic Testing

Advances in genetic analysis have dramatically altered the landscape for diagnosis of heritable diseases, and as a result, the understanding of MFS and other related connective tissue disorders has grown rapidly since the early 21st century. Genetic analysis can be used both for diagnosis of a proband, and for screening of potentially affected relatives. On the other hand, with new information comes more questions. Pathogenic variants causal for MFS are found on the FBN1 gene, on chromosome 15q21.1. However, not all variants in this locus are associated with MFS, and some of these may be associated with familial thoracic aortic aneurysms. These are often termed variants of unclear significance. Additionally, there are non-pathogenic variants that do not lead to any clinically relevant syndrome. In current practice, diagnosis of MFS and related diseases has shifted further and further away from clinical diagnosis to a genetic diagnosis (73). However, correct diagnosis of MFS from genetic analysis is only possible when combined with clinical findings.

When heritable connective tissue or aortic disease is suspected, a consultation with a genetic counselor should be considered. However, in the appropriate clinical setting, genetic analysis is not necessary prior to prophylactic aortic root surgery or repair of disabling musculoskeletal or ocular features. The proband may be offered large panel sequencing, which examines a panel of different loci that have been implicated in hereditary aortopathies. If a causal variant is identified, then appropriate clinical follow up and surveillance imaging can be arranged, with a goal of providing prophylactic aortic surgery prior to aortic dissection or development of irreversible heart failure. If a causal variant, or a variant of unknown significance (VUS) is identified, but clinical criteria are not met, the diagnosis may be better described as the MASS phenotype (mitral valve prolapse (M), nonprogressive aortic root dilatation (A), musculoskeletal findings (S), and skin striae (S); OMIM# 604308), Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome, the Weill-Marchesani syndrome, familial thoracic aortic aneurysm, or familial thoracic aortic dissection. Further differential diagnosis must then be based on clinical criteria (6). It is important to note that our understanding of the role of isolated VUS and the interplay between VUS, bicuspid aortic valve disease, and less severe causal variants is incomplete.

Specific variants do impact severity of disease and prognosis. For instance, specific variants in the exon 24–32 region, colloquially known as the “neonatal region,” are associated with a severe prognosis with death in the first few years of life (37). Probands with premature termination codon (PTC), or nonsense variants had significantly reduced extracellular fibrillin deposition in addition to reduced fibrillin synthesis, whereas individuals with mis-sense cysteine substitutions had normal levels of fibrillin synthesis accompanied by reduced matrix deposition (7, 37, 101). Genotype-phenotype correlations are further complicated by clinical heterogeneity among individuals with the same variant.

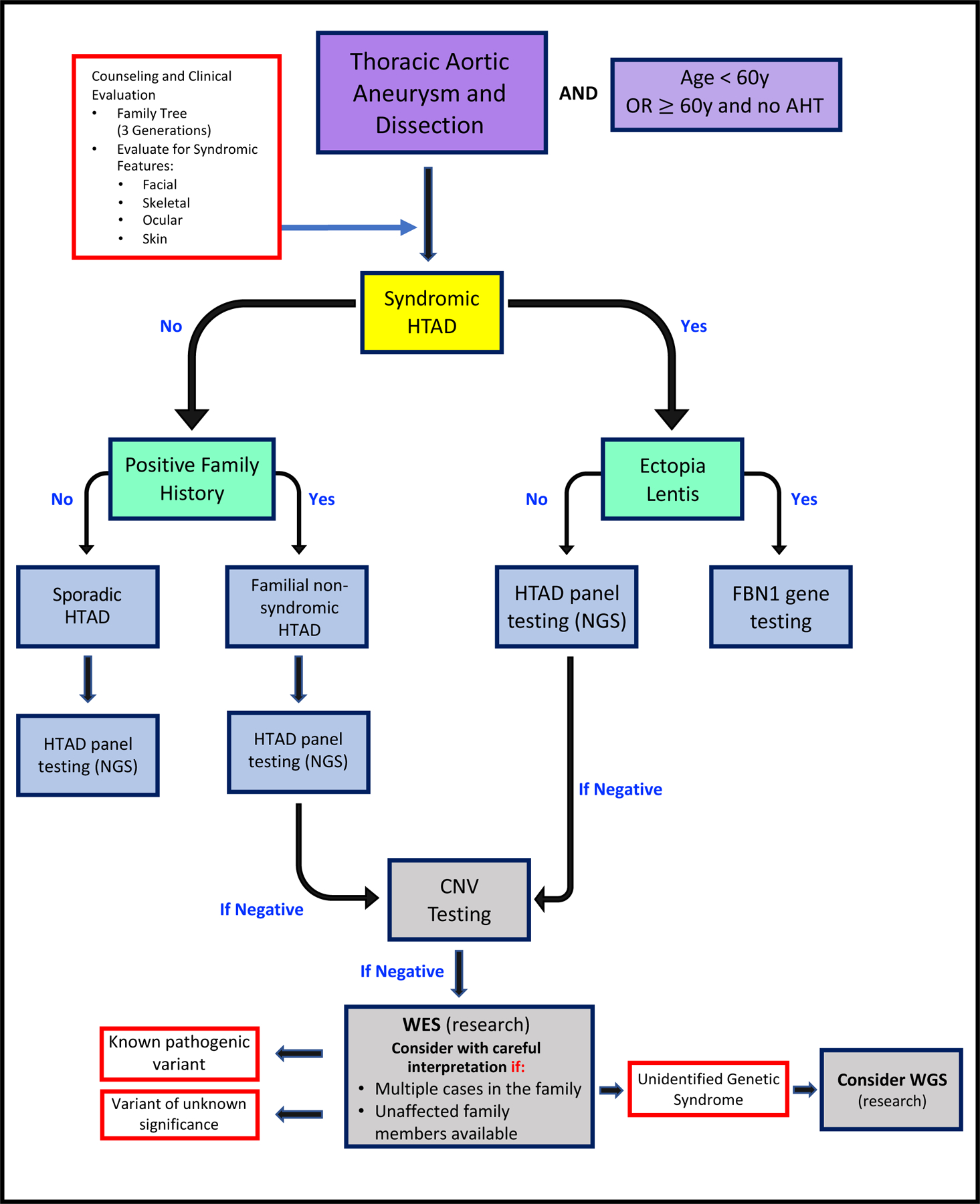

Genetic screening may also differentiate MFS from other related disorders arising from genetic variants remote from FBN1. These panels also screen for other potential pathogenic variants in a wide array of genes, such as TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, which may lead to Loeys-Dietz Syndrome; COL3A1 leading to vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome; and ACTA2, the SMAD family of genes, and NOTCH genes. These panels may identify variants associated with both syndromic and non-syndromic hereditary aneurysm clusters (expertly reviewed by De Backer, et al. (26)). Once a specific variant is identified, the family group may choose to undergo focused cascade screening, which screens relatives only for the variant identified in the proband. Cascade screening is typically less expensive and can be done more quickly than large panel screening (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genetic Testing Flow Chart.

(Adapted from De Backera, J. et al.; Curr Opin Cardiol 34:585–593; 2019). Flowchart for the process of genetic evaluation in heritable thoracic aortic disease. AHT, arterial hypertension; CNV, copy number variants; HTAD, heritable thoracic aortic disease; NGS, next generation sequencing; WES, whole-exome sequencing; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Despite significant progress made in understanding the genetic and molecular basis of MFS, the diagnosis continues to depend heavily on clinical features described in the 2010 Ghent nosology, however, with the 2010 revision, genetic testing is playing a larger role in diagnosis (4).

4.2. Management and Treatment of MFS in the Pediatric Population

All possible cases of MFS in the pediatric population should be regularly assessed by echocardiography, optometry, and skeletal survey as the child grows. Children often have an evolving phenotype and commonly need to be followed for several years before a MFS diagnosis can be confirmed (99). Early referral to a cardiologist and clinical geneticist is key. Repair of pectus deformity should be postponed until the adolescent growth spurt is completed unless there is cardiopulmonary compromise. Severe scoliosis may require surgical stabilization (61). These operations should be performed at centers with experience managing Marfan patients based on commonly used operative criteria.

All Patients with MFS should undergo a yearly evaluation with a pediatric cardiologist to include physical exam and imaging of the aorta (72). The preferred imaging modality is echocardiography in the majority of patients. In patients who are unable to be properly imaged with echocardiography due to either obesity or extreme pectus deformity, MRI or CT scanning can be used yearly for follow up; though MRI is preferred to avoid radiation exposure whenever practical (72). In patients with an aortic root dimension above 4 cm, aortic root growth of more than 0.5 cm/year, or those involved in competitive sports, it is recommended to obtain aortic imaging every 6 months (72).

Lifestyle modifications are another mainstay in the management of MFS. It is generally advised that children with MFS avoid isometric exercise, high impact sports, and competitive sports due to the risk of aortic dissection, long bone fractures, and retinal detachment. However, most patients should be encouraged to remain active with aerobic activities performed in moderation (63).

The commonly prescribed use of β-blockers for MFS patients is intended to reduce hemodynamic stress on the aortic wall and is considered by many to be the standard of care (96). Data supporting the therapeutic benefits of this class of drugs is conflicting, and controversy remains regarding the true benefit of β-blockade (98). If the decision is made to use β-blockers it must be titrated to clinical guidelines. While studies using murine models of MFS, demonstrated the utility of Losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, in slowing aortic growth and preventing dissection, multiple randomized controlled human trials have been unable to consistently reproduce this effect (40, 70, 79). When comparing losartan monotherapy to combination therapy with β-blockade, two studies have shown slower rates of aneurysm progression in the combination therapy (40, 80). A recent meta-analysis concluded that ARB therapy and in combination with β-blockade, was capable of slowing the rate of aortic root dilation but did not change the rate of aortic complications and surgery (3). Accordingly, the use of ARBs may also favorably affect myocardial fibrosis, aortic stiffening, and circulating TGF-β levels (65). We recommend ARB as first line therapy, with the addition of β-blockade as tolerated.

4.3. Management and Treatment of MFS in the Adult Population

Management of the adult with MFS revolves around medical drug therapy, lifestyle management, and appropriate surveillance of aortic and cardiac disease. The relative merits of β-blockade versus ARBs are as controversial in adults as in children, based on the same trial data. Hypertension should be avoided, with goal resting blood pressure <130/80. Most cardiologists and aortic surgeons initiate prophylactic ARB or β-blocker therapy as tolerated, regardless of blood pressure. Both hydralazine and calcium channel blockers should be avoided in MFS patients, as these may be associated with higher rates of aortic dissection and death (34). Furthermore, fluoroquinolones should be strongly avoided in patients with MFS, as multiple studies have demonstrated these medications are associated with de novo aneurysm formation, rapid aneurysmal dilation, and higher rates of dissection (71).

Lifestyle recommendations for adults are similar to those for children. High impact and isometric exercise, as well as competitive athletic pursuits should be avoided, though moderate aerobic exercise is generally recommended. Activities with dynamic atmospheric pressures, i.e. scuba and extreme altitude, should be avoided given the risk of spontaneous pneumothorax (66). It should be noted, there is little real-world data to support these lifestyle recommendations, however, they are unlikely to cause harm. Other cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, should be managed accordingly.

4.4. Cardiovascular management

4.4.1. Imaging Surveillance

Imaging of the aortic root with echocardiography is recommended at the time of diagnosis, and at 6 month intervals after diagnosis in order to quantify baseline aortic root dimensions and initial rate of growth. Echocardiography will also determine the presence of any mitral valve pathology. Bi-annual transthoracic echocardiography should be considered if the maximal aortic dimension is greater than 4.5 cm.

It is important to note that size recommendations for intervention are based on cross-sectional imaging, not echocardiographic dimensions. CT measurements report the external dimension and tend to be a few millimeters larger than echocardiographic measurements (104). Gated CT angiography should be performed if surgical repair is considered.

Surgical referral for prophylactic root replacement should be sought when the maximal aortic dimension reaches 5.0 cm. Other indications for prophylactic root replacement include rapid growth (>0.5cm/yr), family history of dissection at smaller dimensions, or concomitantly when the primary indication is severe aortic or mitral valve regurgitation. For shorter patients and children, an aortic-height index greater than 10 has been associated with higher risk of dissection (78).

Often, a diagnosis of MFS is not made until after emergency treatment of a Stanford Type A aortic dissection. Following dissection repair, cross-sectional imaging should be obtained at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually to watch for aneurysmal dilation of the remaining aortic segments.

4.4.2. Surgical Management

The historic gold standard for treating aortic root aneurysm with or without aortic valve regurgitation in a patient with MFS is root replacement with a composite valved-graft (CVG), which incorporates a mechanical aortic valve into an aortic prosthesis (the Bentall procedure). This approach allows for resection of the aortic root and ascending aorta, as well as a durable, competent aortic prosthesis (11). This approach still exposes the patient to lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin, as well as a significant risk of thromboembolic events, life threatening bleeding, and prosthetic valve endocarditis. Important refinements in surgical technique have led to the David technique becoming the preferred operation for prophylactic root replacement in the young, including in MFS patients. This technique, also known as aortic valve reimplantation, or less precisely, valve-sparing root replacement (VSARR), preserves the native aortic valve leaflets and can often restore competence to even a severely regurgitant valve, provided that there is limited pathology to the leaflets (25). A recent meta-analysis comparing VSARR to CVG in Marfan patients demonstrated very significant reductions in late complications including bleeding, thromboembolism, endocarditis, and mortality, with no difference in the need for reoperation. Overall survival for the entire cohort was excellent: 97.8% at 1 year and 90.5% at 10 years (39).

Another interesting approach involves a custom-made external support, which becomes incorporated into the aortic wall to prevent dilation. Personalized external aortic root support (PEARS) was developed by an engineer with MFS, who then became the first patient in 2004. Mid-term follow up of the first 24 patients was published in 2018 and showed stability of the aortic root and ascending aorta, though 2 patients had technical failure of the operation (60).

Patients presenting with an acute Type A dissection are much more difficult to manage, and often there is no opportunity for patient transfer to a high-volume aortic center without risking patient death. However, there is clear evidence that a more aggressive index operation, including root replacement and extension of the repair to the arch, results in less reoperation (95). Failure to replace the aortic root in the index operation led to a 40% reintervention rate in their series.

The management of Type B aortic dissection in Marfan patients remains controversial. Traditionally, endovascular techniques have been avoided due to poor outcomes in the early experience with the technology. In low-risk patients with chronic dissection related thoracoabdominal aortic disease, open repair remains the treatment of choice on account of its reproducibility and high rate of technical success compared with TEVAR.

Open repair in the acute setting leads to poor outcomes; this has been largely abandoned except in rare circumstances. Outside of connective tissue disease, the use of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), even in uncomplicated dissection, is becoming more common. While initial experience with TEVAR in patients with connective tissue disorders was promising, due to the young age of the patients at implantation, the instability of the landing zones, a high rate of reintervention, and late complications was not uncommon (86). The advantage to early TEVAR would include favorable remodeling by covering the primary tear. The debate continues as to whether this actually lessens the need for open thoracic aortic repairs (23).

4.4.3. Mitral Valve Repair

Mitral valve pathology may present anytime in the course of a MFS patient’s life. As previously discussed, bileaflet pathology is common, including prolapse and chordal rupture. Annular dilatation is also common. The indications for repair or replacement are not different for Marfan patients, and surgical repair should be considered when severe mitral regurgitation is present, regardless of symptoms or ventricular pathology (87). The presence of left ventricular myocardial dysfunction, heart failure symptoms, or atrial fibrillation is a strong indication for surgery. Despite concerns about repair failure, MFS patients who undergo mitral valve repair, rather than replacement, have improved long term survival and this is the preferred strategy (43, 46, 55). Similar concerns about long term bleeding, thromboembolism, and infection apply for mitral valve surgery.

4.3.2. Treatment of MFS in Pregnancy

Pregnancy with MFS requires special attention. There are important considerations regarding prophylactic surgery and the risk for Type B dissection. The negative effects of Warfarin on fetal development, and the risk for dissection associated with lactation following delivery are key concerns. These patients need to be managed by a high-risk obstetrician, preferably at a medical center with expertise in aortic surgery and management of MFS patients.

5.0. Clinical Trials

Results from the early animal studies demonstrating that treatment with losartan, an already FDA approved ARB, could attenuate many of the MFS disease sequelae, stimulated physicians worldwide to start prescribing losartan to patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms secondary to MFS. As noted by Hoffmann Bowman and colleagues, this occurred well before randomized clinical trials of losartan had begun, in many cases in place of β-blocker therapy (57). Nonetheless, these animal studies served as a foundation for designing and implementing a series of exciting clinical trials that had the potential to change the medical management of MFS forever. The first landmark study was a small clinical trial that specifically recruited pediatric MFS patients with severe aortic root enlargement, that had already received β-blocker therapy that failed to reduce aortic root enlargement (13). These patients received ARB therapy and were followed for 12–47 months. The results demonstrated that losartan was able to delay aortic root dilatation from 3.54+/−2.87 mm per year during previous β-blocker therapy to 0.46+/−0.62 mm per year during ARB therapy (P<0.001) (13). This early indication of success continued to feed the excitement and led to the initiation of multiple randomized clinical trials world-wide.

The first prospective trial assessed 233 Dutch MFS patients that were older than 18 years of age and were given losartan in addition to standard of care therapy (COMPARE trial), which often included a β-blocker (51). The results were reported after 3 years of follow-up and suggested that losartan significantly reduced aortic root dilatation as compared to standard therapy alone. It was also reported, however that more patients receiving losartan were taking a β-blocker than in the standard of care treatment group (51).Moreover, a substudy of this trial reported that of 117 patients that underwent FBN1 mutation analysis, there was a statically significant response to losartan in those patients that had FBN1 haploinsufficiency (reduced protein content, with normal protein function) versus FBN1 missense mutations (normal protein content, with aberrant protein function) (51).

The next clinical trial to report results was completed in the US and sponsored by the Pediatric heart Network (PHN). This randomized trial enrolled 608 MFS patients with aortic root enlargement and compared losartan with atenolol directly in children and young adults. The primary outcome measure was the rate of aortic-root enlargement indexed to body-surface area, measured over a 3-year period (70). Unfortunately, the results revealed that there no significant difference in aortic-root dilatation rate after three years, as measured by standardized echocardiography, between patients randomized to the two treatment groups.

Shortly thereafter, a small parallel, randomized, double-blind study was initiated in Spain with 140 patients, using the same study design as the PHN (40). After 3 years of follow-up this study likewise showed no change in aortic root diameter between the two group, demonstrating no benefit of losartan over atenolol. Furthermore, follow-up of 128 of these patients at 6.7 years after receiving initial treatment, still failed to show a difference in aortic root diameter between the treatment groups (40).

Importantly, the PHN and Spanish trials did not indicate that losartan was ineffective, it suggested only that it was equivocal with atenolol treatment, showing no specific benefit over standard of care. Interestingly, in the COMPARE trial substudy in which losartan was given in combination with β-blocker therapy, results suggested that there was a possible benefit in combination therapy. Accordingly, the “Marfan-Sartan” study addressed this question directly (79). This study was a double-blind, randomized, multi-center, placebo-controlled, add-on trial that compared losartan vs. placebo in MFS patients that were older than 10 years of age. After 3.5 years of follow-up the 303 patients enrolled showed no difference in aortic root diameter (79). In contrast to these results, the Aortic Irbesartan Marfan Study (AIMS) examined 192 patients with MFS that were receiving standard of care (in which approximately 56% of the patients were receiving a β-blocker) and randomized them to receive either irbesartan or a placebo (80). The mean baseline aortic root diameter was 34.4 mm both groups at the start of the study. After 5-years of follow-up, the mean rate of aortic root dilatation was 0.53 mm per year in the irbesartan group, versus 0.74 mm per year in the placebo group, representing a statistically significant reduction in aortic root dilatation of −0.22 mm per year (80). Importantly, irbesartan was well tolerated in both treatment groups, even in children.

While most of these clinical trials showed no benefit of ARB (losartan) over β-blocker (atenolol) therapy, there are a couple of important conclusions that came out of this work. First, there may be some hope in combining ARB and β-blocker therapies. Two of the smaller studies demonstrated benefit with the drug combination. Furthermore, the use of different β-blockers or ARBs may contribute to improved responses. Second, as additional studies began to look at the specific associations between genotype and phenotype, there may be subsets of patients that respond better than others. For example, as indicated above in the COMPARE trial, MFS patients that were FBN1 haploinsufficient, responded better to losartan than those that had missense mutations (41). The authors hypothesized that haploinsufficient patients may have a weaker aortic wall due to reduced FBN1 content, leading to enhanced mechanotransduction as a result of aortic dilatation and enhanced activation of the mechanosensitive angiotensin receptor pathway. Clearly further studies are warranted to delineate this and other genotype-phenotype associations and may suggest that additional treatment strategies are needed for MFS patients with dominant negative FBN1 mutations.

6.0. Conclusions

While the recent equivocal clinical trial results comparing ARB therapy versus β-blockade, have not been able to perfectly replicate the early promising animal studies, new data continues to build on the suggestion that combination therapy may provide the best benefit to all patients for now. Nonetheless, current therapeutic standards (β-blocker therapy) and prophylactic aortic root replacement, have extended the life of MFS patients to near normal. They are living longer and are now having to deal with medical issues related to later onset symptoms including joint disease and aneurysm of the descending thoracic aorta. Moreover, as genetic testing becomes increasingly prevalent in diagnosis and classification, additional data examining the FBN1 haploinsufficient genotype-phenotype association with ARB therapy response will certainly provide new insights and potential treatment options. Importantly, this highlights the need to develop additional therapeutic strategies to address those patients with less favorable genotypes. Overall, few medical discoveries in history have been elucidated to the degree that MFS has seen. From the early indications of a heritable disorder, to the identification of the gene responsible, to discerning the complex pathogenesis, culminating in rationale clinical trial design, the degree of thought and investment from the countless physicians and scientists involved has facilitated the truly remarkable progress that has been made in understanding this disorder.

7.0 Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Merit Review I01 BX000904 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service.

8.0 References

- 1.Aalberts JJ, Waterbolk TW, van Tintelen JP, Hillege HL, Boonstra PW, and van den Berg MP. Prophylactic aortic root surgery in patients with Marfan syndrome: 10 years’ experience with a protocol based on body surface area. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 34: 589–594, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, Garrett ES, Sieber AN, and Kostuik JP. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: a meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine 25: 1515–1522, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Abcha A, Saleh Y, Mujer M, Boumegouas M, Herzallah K, Charles L, Elkhatib L, Abdelkarim O, Kehdi M, and Abela GS. Meta-analysis Examining the Usefulness of Angiotensin Receptor blockers for the Prevention of Aortic Root Dilation in Patients With the Marfan Syndrome. Am J Cardiol 128: 101–106, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammash NM, Sundt TM, and Connolly HM. Marfan syndrome-diagnosis and management. Curr Probl Cardiol 33: 7–39, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annes JP, Munger JS, and Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci 116: 217–224, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arslan-Kirchner M, von Kodolitsch Y, and Schmidtke J. The importance of genetic testing in the clinical management of patients with Marfan syndrome and related disorders. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105: 483–491, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubart M, Gazal S, Arnaud P, Benarroch L, Gross MS, Buratti J, Boland A, Meyer V, Zouali H, Hanna N, Milleron O, Stheneur C, Bourgeron T, Desguerre I, Jacob MP, Gouya L, Genin E, Deleuze JF, Jondeau G, and Boileau C. Association of modifiers and other genetic factors explain Marfan syndrome clinical variability. Eur J Hum Genet 26: 1759–1772, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baer RW, Taissig HB, and Oppenheimer EH. Congenital aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta associated with arachnodactyly. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 72: 309, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beals RK and Hecht F. Congenital contractural arachnodactyly. A heritable disorder of connective tissue. J Bone Joint Surg Am 53: 987–993, 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beighton P, de Paepe A, Danks D, Finidori G, Gedde-Dahl T, Goodman R, Hall JG, Hollister DW, Horton W, McKusick VA, and et al. International Nosology of Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue, Berlin, 1986. Am J Med Genet 29: 581–594, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentall H and De Bono A. A technique for complete replacement of the ascending aorta. Thorax 23: 338–339, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boerger F Ueber zwei Fälle von Arachnodaktylie. Monatsschr Kinderheilk 13: 335, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooke BS, Habashi JP, Judge DP, Patel N, Loeys B, and Dietz HC 3rd. Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 358: 2787–2795, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown OR, DeMots H, Kloster FE, Roberts A, Menashe VD, and Beals RK. Aortic root dilatation and mitral valve prolapse in Marfan’s syndrome: an ECHOCARDIOgraphic study. Circulation 52: 651–657, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carta L, Smaldone S, Zilberberg L, Loch D, Dietz HC, Rifkin DB, and Ramirez F. p38 MAPK is an early determinant of promiscuous Smad2/3 signaling in the aortas of fibrillin-1 (Fbn1)-null mice. J Biol Chem 284: 5630–5636, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra A, Ekwalla V, Child A, and Charteris D. Prevalence of ectopia lentis and retinal detachment in Marfan syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol 92: e82–83, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charbonneau NL, Ono RN, Corson GM, Keene DR, and Sakai LY. Fine tuning of growth factor signals depends on fibrillin microfibril networks. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 72: 37–50, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhry SS, Cain SA, Morgan A, Dallas SL, Shuttleworth CA, and Kielty CM. Fibrillin-1 regulates the bioavailability of TGFbeta1. J Cell Biol 176: 355–367, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Child AH. Non-cardiac manifestations of Marfan syndrome. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 6: 599–609, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke CC. Ectopia lentis: a pathologic and clinical study. Archives of Ophthalmology 21. 1: 124–153, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook JR, Carta L, Benard L, Chemaly ER, Chiu E, Rao SK, Hampton TG, Yurchenco P, Gen TACRC, Costa KD, Hajjar RJ, and Ramirez F. Abnormal muscle mechanosignaling triggers cardiomyopathy in mice with Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest 124: 1329–1339, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook JR and Ramirez F. Clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects of the Marfan syndrome. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 802: 77–94, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper DG, Walsh SR, Sadat U, Hayes PD, and Boyle JR. Treating the thoracic aorta in Marfan syndrome: surgery or TEVAR? J Endovasc Ther 16: 60–70, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daugherty A, Manning MW, and Cassis LA. Antagonism of AT2 receptors augments angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol 134: 865–870, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.David TE and Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 103: 617–621; discussion 622, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Backer J, Jondeau G, and Boileau C. Genetic testing for aortopathies: primer for the nongeneticist. Curr Opin Cardiol 34: 585–593, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Beaufort HWL, Trimarchi S, Korach A, Di Eusanio M, Gilon D, Montgomery DG, Evangelista A, Braverman AC, Chen EP, Isselbacher EM, Gleason TG, De Vincentiis C, Sundt TM, Patel HJ, and Eagle KA. Aortic dissection in patients with Marfan syndrome based on the IRAD data. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 6: 633–641, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Paepe A, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Hennekam RC, and Pyeritz RE. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet 62: 417–426, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietz HC, Cutting GR, Pyeritz RE, Maslen CL, Sakai LY, Corson GM, Puffenberger EG, Hamosh A, Nanthakumar EJ, Curristin SM, and et al. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature 352: 337–339, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietz HC, Loeys B, Carta L, and Ramirez F. Recent progress towards a molecular understanding of Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 139C: 4–9, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dietz HC, McIntosh I, Sakai LY, Corson GM, Chalberg SC, Pyeritz RE, and Francomano CA. Four novel FBN1 mutations: significance for mutant transcript level and EGF-like domain calcium binding in the pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome. Genomics 17: 468–475, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietz HC and Pyeritz RE. Mutations in the human gene for fibrillin-1 (FBN1) in the Marfan syndrome and related disorders. Hum Mol Genet 4 Spec No: 1799–1809, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietz HC, Pyeritz RE, Hall BD, Cadle RG, Hamosh A, Schwartz J, Meyers DA, and Francomano CA. The Marfan syndrome locus: confirmation of assignment to chromosome 15 and identification of tightly linked markers at 15q15-q21.3. Genomics 9: 355–361, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doyle JJ, Doyle AJ, Wilson NK, Habashi JP, Bedja D, Whitworth RE, Lindsay ME, Schoenhoff F, Myers L, Huso N, Bachir S, Squires O, Rusholme B, Ehsan H, Huso D, Thomas CJ, Caulfield MJ, Van Eyk JE, Judge DP, Dietz HC, Gen TACRC, and Consortium ML. A deleterious gene-by-environment interaction imposed by calcium channel blockers in Marfan syndrome. Elife 4, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etter LE and Glover LP. Arachnodactyly Complicated by Dislocated Lens and Death From Dissecting Aneurysm of the Aorta. JAMA 123: 88, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Everett AD, Tufro-McReddie A, Fisher A, and Gomez RA. Angiotensin receptor regulates cardiac hypertrophy and transforming growth factor-beta 1 expression. Hypertension 23: 587–592, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faivre L, Collod-Beroud G, Loeys BL, Child A, Binquet C, Gautier E, Callewaert B, Arbustini E, Mayer K, Arslan-Kirchner M, Kiotsekoglou A, Comeglio P, Marziliano N, Dietz HC, Halliday D, Beroud C, Bonithon-Kopp C, Claustres M, Muti C, Plauchu H, Robinson PN, Ades LC, Biggin A, Benetts B, Brett M, Holman KJ, De Backer J, Coucke P, Francke U, De Paepe A, Jondeau G, and Boileau C. Effect of mutation type and location on clinical outcome in 1,013 probands with Marfan syndrome or related phenotypes and FBN1 mutations: an international study. Am J Hum Genet 81: 454–466, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figueiredo S, Martins E, Lima MR, and Alvares S. Cardiovascular manifestations in Marfan syndrome. Rev Port Cardiol 20: 1203–1218, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn CD, Tian DH, Wilson-Smith A, David T, Matalanis G, Misfeld M, Mastrobuoni S, El Khoury G, and Yan TD. Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical outcomes in Marfan patients undergoing aortic root surgery by composite-valve graft or valve sparing root replacement. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 6: 570–581, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forteza A, Evangelista A, Sanchez V, Teixido-Tura G, Sanz P, Gutierrez L, Gracia T, Centeno J, Rodriguez-Palomares J, Rufilanchas JJ, Cortina J, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, and Garcia-Dorado D. Efficacy of losartan vs. atenolol for the prevention of aortic dilation in Marfan syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. European heart journal 37: 978–985, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franken R, den Hartog AW, Radonic T, Micha D, Maugeri A, van Dijk FS, Meijers-Heijboer HE, Timmermans J, Scholte AJ, van den Berg MP, Groenink M, Mulder BJ, Zwinderman AH, de Waard V, and Pals G. Beneficial Outcome of Losartan Therapy Depends on Type of FBN1 Mutation in Marfan Syndrome. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics 8: 383–388, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukuda N, Hu WY, Kubo A, Kishioka H, Satoh C, Soma M, Izumi Y, and Kanmatsuse K. Angiotensin II upregulates transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor on rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Hypertens 13: 191–198, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuzellier JF, Chauvaud SM, Fornes P, Berrebi AJ, Lajos PS, Bruneval P, and Carpentier AF. Surgical management of mitral regurgitation associated with Marfan’s syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 66: 68–72, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ge G and Greenspan DS. BMP1 controls TGFbeta1 activation via cleavage of latent TGFbeta-binding protein. J Cell Biol 175: 111–120, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gehle P, Goergen B, Pilger D, Ruokonen P, Robinson PN, and Salchow DJ. Biometric and structural ocular manifestations of Marfan syndrome. PLoS One 12: e0183370, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillinov AM, Hulyalkar A, Cameron DE, Cho PW, Greene PS, Reitz BA, Pyeritz RE, and Gott VL. Mitral valve operation in patients with the Marfan syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 107: 724–731, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldfinger JZ, Preiss LR, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Hendershot TP, Kroner BL, Eagle KA, and Gen TACRC. Marfan Syndrome and Quality of Life in the GenTAC Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 2821–2830, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gott VL, Greene PS, Alejo DE, Cameron DE, Naftel DC, Miller DC, Gillinov AM, Laschinger JC, and Pyeritz RE. Replacement of the aortic root in patients with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 340: 1307–1313, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goyette EM and Palmer PW. Cardiovascular Lesions in Arachnodactyly. Circulation 7: 363, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grahame R and Pyeritz RE. The Marfan syndrome: joint and skin manifestations are prevalent and correlated. Br J Rheumatol 34: 126–131, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groenink M, den Hartog AW, Franken R, Radonic T, de Waard V, Timmermans J, Scholte AJ, van den Berg MP, Spijkerboer AM, Marquering HA, Zwinderman AH, and Mulder BJ. Losartan reduces aortic dilatation rate in adults with Marfan syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. European heart journal 34: 3491–3500, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groth KA, Stochholm K, Hove H, Andersen NH, and Gravholt CH. Causes of Mortality in the Marfan Syndrome(from a Nationwide Register Study). Am J Cardiol 122: 1231–1235, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, Holm TM, Aziz H, Schoenhoff F, Bedja D, Chen Y, Modiri AN, Judge DP, and Dietz HC. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science 332: 361–365, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Cooper TK, Myers L, Klein EC, Liu G, Calvi C, Podowski M, Neptune ER, Halushka MK, Bedja D, Gabrielson K, Rifkin DB, Carta L, Ramirez F, Huso DL, and Dietz HC. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science 312: 117–121, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Helder MR, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, Li Z, Stulak JM, Suri RM, and Connolly HM. Management of mitral regurgitation in Marfan syndrome: Outcomes of valve repair versus replacement and comparison with myxomatous mitral valve disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 148: 1020–1024; discussion 1024, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hennekam RC. Severe infantile Marfan syndrome versus neonatal Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 139: 1, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofmann Bowman MA, Eagle KA, and Milewicz DM. Update on Clinical Trials of Losartan With and Without beta-Blockers to Block Aneurysm Growth in Patients With Marfan Syndrome: A Review. JAMA Cardiol 4: 702–707, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holm TM, Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, Bedja D, Chen Y, van Erp C, Lindsay ME, Kim D, Schoenhoff F, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Thomas CJ, Patnaik S, Marugan JJ, Judge DP, and Dietz HC. Noncanonical TGFbeta signaling contributes to aortic aneurysm progression in Marfan syndrome mice. Science 332: 358–361, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isogai Z, Ono RN, Ushiro S, Keene DR, Chen Y, Mazzieri R, Charbonneau NL, Reinhardt DP, Rifkin DB, and Sakai LY. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 1 interacts with fibrillin and is a microfibril-associated protein. J Biol Chem 278: 2750–2757, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Izgi C, Newsome S, Alpendurada F, Nyktari E, Boutsikou M, Pepper J, Treasure T, and Mohiaddin R. External Aortic Root Support to Prevent Aortic Dilatation in Patients With Marfan Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 1095–1105, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones KB, Erkula G, Sponseller PD, and Dormans JP. Spine deformity correction in Marfan syndrome. Spine 27: 2003–2012, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Judge DP, Biery NJ, Keene DR, Geubtner J, Myers L, Huso DL, Sakai LY, and Dietz HC. Evidence for a critical contribution of haploinsufficiency in the complex pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest 114: 172–181, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Judge DP and Dietz HC. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet 366: 1965–1976, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Judge DP, Rouf R, Habashi J, and Dietz HC. Mitral valve disease in Marfan syndrome and related disorders. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 4: 741–747, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karur GR, Pagano JJ, Bradley T, Lam CZ, Seed M, Yoo SJ, and Grosse-Wortmann L. Diffuse Myocardial Fibrosis in Children and Adolescents With Marfan Syndrome and Loeys-Dietz Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 72: 2279–2281, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keane MG and Pyeritz RE. Medical management of Marfan syndrome. Circulation 117: 2802–2813, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kielty CM, Baldock C, Lee D, Rock MJ, Ashworth JL, and Shuttleworth CA. Fibrillin: from microfibril assembly to biomechanical function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357: 207–217, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kielty CM, Sherratt MJ, Marson A, and Baldock C. Fibrillin microfibrils. Adv Protein Chem 70: 405–436, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kurucan E, Bernstein DN, Ying M, Li Y, Menga EN, Sponseller PD, and Mesfin A. Trends in spinal deformity surgery in Marfan syndrome. Spine J 19: 1934–1940, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lacro RV, Dietz HC, Sleeper LA, Yetman AT, Bradley TJ, Colan SD, Pearson GD, Selamet Tierney ES, Levine JC, Atz AM, Benson DW, Braverman AC, Chen S, De Backer J, Gelb BD, Grossfeld PD, Klein GL, Lai WW, Liou A, Loeys BL, Markham LW, Olson AK, Paridon SM, Pemberton VL, Pierpont ME, Pyeritz RE, Radojewski E, Roman MJ, Sharkey AM, Stylianou MP, Wechsler SB, Young LT, Mahony L, and Pediatric Heart Network I. Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 371: 2061–2071, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee CC, Lee MT, Chen YS, Lee SH, Chen YS, Chen SC, and Chang SC. Risk of Aortic Dissection and Aortic Aneurysm in Patients Taking Oral Fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 175: 1839–1847, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindsay ME. Medical management of aortic disease in children with Marfan syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr 30: 639–644, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, Callewaert BL, De Backer J, Devereux RB, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Jondeau G, Faivre L, Milewicz DM, Pyeritz RE, Sponseller PD, Wordsworth P, and De Paepe AM. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet 47: 476–485, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lundby R, Rand-Hendriksen S, Hald JK, Lilleas FG, Pripp AH, Skaar S, Paus B, Geiran O, and Smith HJ. Dural ectasia in Marfan syndrome: a case control study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30: 1534–1540, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marfan AB. Un cas de deformation congenitale des quatre membres, plus prononcee aux extremitds, characteriske par l’allongement des os avec un certain degre d’amincissement. Bull et mom Soc med hop Paris 13: 220, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKusick VA. The cardiovascular aspects of Marfan’s syndrome: a heritable disorder of connective tissue. Circulation 11: 321–342, 1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McKusick VA. Heritable disorders of connective tissue. III. The Marfan syndrome. J Chronic Dis 2: 609–644, 1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Milewicz DM, Dietz HC, and Miller DC. Treatment of aortic disease in patients with Marfan syndrome. Circulation 111: e150–157, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]