Abstract

The impact of acidification and alkalinization of urine on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin was investigated after single 200-mg oral doses were administered to nine healthy male volunteers. In addition, the effect of human urine on the MICs of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin against some common urinary tract pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was investigated. Acidic and alkaline conditions were achieved by repeated oral doses of ammonium chloride or sodium bicarbonate, respectively. Plasma ciprofloxacin levels in all subjects were adequately described in terms of two-compartment model kinetics with first-order absorption. Acidification and alkalinization treatments had no effect on ciprofloxacin absorption, distribution, or elimination. The total amount of unchanged ciprofloxacin excreted over 24 h under acidic conditions was 88.4 ± 14.5 mg (mean ± standard deviation) (44.2% of the oral dose) and 82.4 ± 16.5 mg (41.2% of the oral dose) under alkaline conditions, while the total amount of unchanged drug excreted over 24 h in volunteers receiving neither sodium bicarbonate nor ammonium chloride was 90.53 ± 9.8 mg (45.2% of the oral dose). The mean renal clearance of ciprofloxacin was 16.78 ± 2.67, 16.08 ± 3.2, and 16.31 ± 2.67 liters/h with acidification, alkalinization, and control, respectively. Renal clearance and concentrations of ciprofloxacin in urine were not correlated with urinary pH. The antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin against E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was affected by human urine and in particular by its pH. The activities of both quinolones against E. coli NIHJ JC-2 were lower at lower urinary pH and rather uniform, while in the case of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 ciprofloxacin was more active than sparfloxacin.

Ciprofloxacin has been shown to exhibit an excellent activity against gram-negative pathogens commonly encountered in complicated urinary tract infections (21). It is well absorbed from oral doses and is rapidly excreted from the body under normal conditions, with an elimination half-life of 3 to 5 h (9).

It has been emphasized that physicochemical proprieties of quinolones have major consequences for their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (13, 19). Piperazine-substituted quinolones such as ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin exhibit two protonation sites in the molecule. At physiologic pH, ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin exist primarily as zwitterions. The percentage of these zwitterion antibiotics ionized is pH dependent (20). A previous study revealed a significant effect of urinary pH on the renal clearance of sparfloxacin (8). However, there are no studies investigating the effect of urinary pH on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin. In view of the importance of urinary ciprofloxacin concentrations for the treatment of urinary tract infections (6–8) and of the major role exerted by the kidneys in ciprofloxacin elimination (9), it is necessary to examine the effect of urinary pH on the pharmacokinetic and antibacterial properties of ciprofloxacin in humans. This study also compares the effects of acidic and basic urines on the antimicrobial activities of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pharmacokinetic study. (i) Subjects.

Nine healthy Japanese male volunteers aged from 21 to 32 years (mean age, 23 years) with a mean body weight of 65 kg participated in this study after written informed consent had been obtained. All subjects were determined to be in good health prior to the study on the bases of physical examination, medical history, and laboratory tests. No other medication and no ingestion of alcohol were permitted 1 week prior to and during the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oita Medical University Hospital.

(ii) Drugs.

Ciprofloxacin was obtained from Bayer Yakuhin Ltd., Osaka, Japan, and ammonium chloride and sodium bicarbonate were obtained from Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan.

(iii) Study design.

The nine subjects received single oral doses of ciprofloxacin (200 mg) on three different occasions by a Latin square design. Treatments were administered 1 week apart. On each occasion the subject’s urinary pH was modified by one of the following treatments started 21 h before and continued for 24 h after administration: (i) no treatment, (ii) 0.4 g of ammonium chloride given every 3 h and 0.8 g given before sleep, or (iii) 1.2 g of sodium bicarbonate every 3 h and 2.4 g before sleep. To maintain urine production, every dose of ammonium chloride or sodium bicarbonate was given with 150 ml of water every 3 h. On the occasions when ciprofloxacin was administered alone, the frequency and volume of water ingestion were identical to those in the other treatments. On the study day at 8:00 a.m., 200 mg of ciprofloxacin was administered with 150 ml of water. For all three treatments, the subjects were not allowed to eat food from 8:00 p.m. on the day before until noon on the day of ciprofloxacin administration. The order of treatments was open and balanced, and the subjects were randomly allocated to the treatments.

(iv) Sample collection.

Sampling was identical for all the subjects. Blood samples (7 ml) were collected in heparinized tubes before and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after drug administration. Samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and plasma aliquots were frozen at −80°C for later analysis. Urine was collected from 0 to 2, 2 to 4, 4 to 6, 6 to 8, 8 to 12, and 12 to 24 h after intake of ciprofloxacin. The pH of the urine was recorded immediately after each collection to minimize pH changes occurring during storage. Urine samples were frozen at −80°C as soon as each volume and pH value had been determined.

(v) Drug analysis.

Plasma and urine samples were analyzed for unchanged ciprofloxacin by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography assays (7). Six concentrations (excluding blank values) defined the standard curves. The linearity of the standard curves was verified from 0.01 to 2.5 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin in plasma and from 0.5 to 500 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin in urine. The correlation coefficients between the peak-area ratio of the drug to the internal standard and concentration were >0.999. The limit of quantification was 0.01 μg/ml of plasma and 0.5 μg/ml of urine. The relation between response and concentrations was demonstrated to be continuous and reproducible. A standard curve was generated for each analytical run and was used to calculate the concentration of ciprofloxacin in the unknown samples assayed with that run. The standard curves covered the entire range of expected concentrations. The specificity of the assay was established with nine independent sources of the same matrix. The accuracy and precision were determined with five determinations per concentration. The mean value was within 15% of the actual value, except at the limit of quantification, where it did not deviate by more than 20%. The procedure had mean intra- and interassay coefficients of variation below 10 and 5% over the concentration ranges in plasma and urine. Recovery from plasma was 96.1, 98.8, and 98.4% for ciprofloxacin at the concentrations 0.01, 0.5, and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively, and the recovery from urine was 95.2, 99.9, and 99.96% for ciprofloxacin at the concentrations 0.5, 50, and 500 μg/ml, respectively. Recovery for the internal standard was 90.8% at the concentration 5 μg/ml from plasma and 92.5% at the concentration 50 μg/ml from urine.

(vi) Pharmacokinetic analyses.

The area under plasma concentration-time curve was estimated by the trapezoidal rule. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated according to a two-compartment open model with first-order absorption. The maximum concentration in plasma (Cmax) and the time to peak concentration in plasma were taken directly from the original data. The renal clearance of the drug was calculated as Ae (0 to 24 h)/AUC (0 to 24 h), where Ae (0 to 24 h) is the amount of unchanged drug excreted in the 0-to-24-h urine.

(vii) Statistical analyses.

Group data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). To describe differences in pharmacokinetic parameters and urinary pH between treatments, the results were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (subjects and treatments) followed by Scheffe’s multiple-range test if appropriate. All P values ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

In vitro antimicrobial study. (i) Bacterial strains.

One clinical strain of Escherichia coli (NIHJ JC-2) and one reference strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) were used.

(ii) Antimicrobial agents.

Ciprofloxacin (Bayer Yakuhin Ltd.) and sparfloxacin (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co.) were used. Stock solutions of the drugs were prepared from standard powders and stored at −70°C until used. On the day of test, antimicrobial agents were diluted into the appropriate medium to achieve the desired concentrations.

(iii) Media.

Cation (Ca2+ and Mg2+)-supplemented Mueller-Hinton Broth (MHB [Difco]; pH 7.2 at 25°C) and pH-adjusted MHBs (pHs 5.8 and 8.0 at 25°C) were used for MIC determinations. The adjustment of pH in MHB was made with hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide solutions. To investigate the influence of divalent cations on the MICs of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin, the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in MHB (pH 7.2) were increased by factors of 2, 5, and 10. The antimicrobial-agent-free human urines were pooled from study subjects after ammonium chloride or sodium bicarbonate treatment and were used for MIC determinations.

(iv) MIC determinations.

Determinations of the MIC were made by the microdilution standard method as described by the Japan Society of Chemotherapy (4, 5). Serial drug dilutions were prepared in broth or 100% urine. In brief, the cultures of E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were suspended and adjusted to approximately 1.0 × 107 CFU/ml in sterile saline. One to five microliters of each bacterial solution was inoculated into a well, which included 0.1 ± 0.02 ml of broth or urine, with a series of drug dilutions, and incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35 ± 1°C. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of drug that prevented visible growth.

(v) Ca2+ and Mg2+ determinations.

Urinary calcium and magnesium concentrations were determined according to the O-cresolphthalein complexon method (6) and xylidil blue method (11), respectively. Three microliters of urine from each subject was directly injected into a Hitachi-7450 autoanalyzer with the reagents provided in the kits for analysis (Calcium-HR II and Magnesium-HR II; Wako, Junyaku, Japan).

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetic study. (i) Urine pH values.

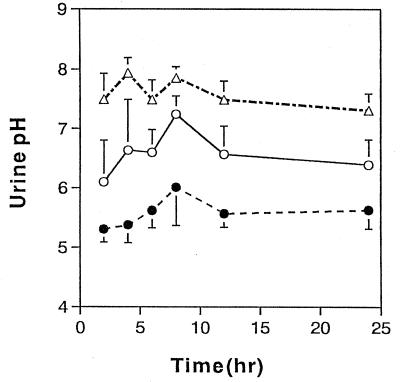

The mean urine pH values obtained after the three treatments are summarized in Fig. 1. Under control conditions, the mean pH varied between 6.1 and 7.24. After ammonium chloride treatment, the pH decreased to 5.32 to 6.02, whereas sodium bicarbonate treatment resulted in an increase in pH to 7.15 to 7.79. The pH differences between treatments were significant (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Changes in the urinary pH over 24 h in healthy subjects treated with ammonium chloride (●), sodium bicarbonate (▵), or water (○). Values represent means ± SDs for nine subjects.

(ii) Pharmacokinetics in plasma.

The mean pharmacokinetic parameters as well as the results of the statistical analysis are summarized in Table 1. Neither the rate nor the extent of ciprofloxacin absorption from the oral dose was significantly affected by changes in urinary pH. Cmax after ammonium chloride treatment was decreased slightly without reaching statistical significance. After ammonium chloride treatment, ciprofloxacin levels in plasma were not detectable at 24 h in three subjects. Treatment with ammonium chloride or sodium bicarbonate did not have any effect on the half-life of ciprofloxacin.

TABLE 1.

Influence of urinary pH on ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics in plasma: a comparison between pharmacokinetic variables on three separate occasions under different conditions of urinary pH

| Pharmacokinetic variablesa | Resultb (SD) under treatment with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NaHCO3 | NH4Cl | H2O | |

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 1.729 (0.33) | 1.506 (0.238) | 1.804 (0.421) |

| Tmax (h) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.4) |

| t1/2 (h) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.2 (0.8) |

| AUC (μg · h/ml) | 5.147 (0.680) | 5.320 (0.770) | 5.649 (0.884) |

| CL/F (liters/h) | 37.971 (6.711) | 39.011 (5.599) | 37.464 (5.194) |

| V/F (liters) | 248.762 (78.602) | 234.484 (46.28) | 223.377 (37.52) |

| CLR (liters/h) | 16.08 (3.02) | 16.78 (2.67) | 16.31 (2.67) |

| Ae (mg) | 82.4 (16.5) | 88.4 (14.5) | 90.53 (9.8) |

Tmax, time to peak concentration in plasma; t1/2, apparent elimination half-life; AUC, area under the plasma concentration-time curve (0 to 24 h); CL/F, apparent total body clearance; V/F, apparent volume of distribution; CLR, renal clearance; Ae, amount of unchanged drug excreted.

The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated according to a two-compartment open model with first-order absorption. ANOVA was utilized to describe significant differences in the pharmacokinetic parameters and urinary pH; all differences were not significant.

(iii) Urinary excretion.

The total amount of unchanged ciprofloxacin excreted over 24 h under acidic conditions was 88.4 ± 14.5 mg (mean ± SD) (44.2% of the oral dose), while under alkaline conditions it was 82.4 ± 16.5 mg (41.2% of the oral dose). The total amount of unchanged drug excreted over 24 h in the subjects under control conditions was 90.5 ± 9.8 mg (45.2% of the oral dose). Statistical comparison of the data showed that urinary excretion of ciprofloxacin was independent of the treatment even when we look at the urinary excretion at various time periods (Tables 1 and 2). The renal clearance of unchanged drug was not correlated with urinary pH (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Amount of unchanged drug excreted into urine at various time periods after treatment with ammonium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, or watera

| Collection period (h) | Amt (mg) of unchanged drug (SD) under treatment with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NaHCO3 | NH4Cl | H2O | |

| 0–2 | 22.426 (9.679) | 24.756 (8.564) | 26.251 (5.156) |

| 2–4 | 20.099 (6.690) | 19.877 (5.327) | 21.988 (9.145) |

| 4–6 | 12.763 (3.253) | 12.695 (5.696) | 13.700 (3.366) |

| 6–8 | 8.220 (2.015) | 11.098 (5.958) | 9.314 (3.884) |

| 8–12 | 10.935 (2.269) | 10.116 (2.546) | 10.598 (2.410) |

| 12–24 | 9.899 (2.604) | 8.304 (3.246) | 8.608 (3.927) |

ANOVA was utilized to describe significant differences; all differences were not significant.

In vitro antimicrobial study. (i) Influence of pH and concentration of cations Ca2+ and Mg2+ on ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin MICs.

Lowering the pH of MHB to 5.8 caused 8- to 31-fold increases in the ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin MICs for E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and 4- to 16-fold increases in the ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin MICs for P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, respectively (Table 3). Lowering of the pH had its greatest effect on the sparfloxacin activity against E. coli NIHJ JC-2, but it showed little effect on the activity of ciprofloxacin against P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853. When concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ in MHB (pH 7.2) were increased by factors of 2, 5, and 10, the MICs of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin were shifted upward twofold for E. coli NIHJ JC-2, but there was no detectable effect of increasing of Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations on the activity of ciprofloxacin against P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Influence of pH and Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations on the MICs of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin

| Strain and drug | MIC [μg/ml (fold increase)] in brotha at pH:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.0 (MHB-A) | 7.2

|

5.8 (MHB-A) | ||||

| MHB-A | MHB-B | MHB-C | MHB-D | |||

| E. coli NIHJ JC-2 | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.016 | 0.031 (2) | 0.031 (2) | 0.063 (4) | 0.063 (4) | 0.125 (8) |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.008 | 0.031 (4) | 0.031 (4) | 0.063 (8) | 0.063 (8) | 0.25 (31) |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.50 | 0.50 (1) | 0.50 (1) | 0.50 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.50 | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 8 (16) |

MHB-A, MHB with concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of 25 and 12.5 mg/liter, respectively; MHB-B, MHB with concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of 50 and 25 mg/liter, respectively; MHB-C, MHB with concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of 125 and 62.5 mg/liter, respectively; MHB-D, MHB with concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of 250 and 125 mg/liter, respectively.

The MICs for E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 cultivated in pooled human urines and the concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ at different pH values are shown in Table 4. The ciprofloxacin MIC range for E. coli NIHJ JC-2 determined in urine at pHs from 5.27 to 6.39 was 0.063 to 0.5 μg/ml, whereas at pHs from 6.84 to 8.1 it was 0.016 to 0.125 μg/ml. The activity of sparfloxacin against E. coli NIHJ JC-2 was influenced in a similar fashion. With P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 cultivated in urine, the MICs of ciprofloxacin at pHs from 5.27 to 6.39 increased about one- or twofold in six subjects and decreased two- or fourfold in three subjects compared with MICs at pHs from 6.84 to 8.1. Lowering of the pH from 6.39 to 5.27 in the case of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 resulted in an increase in MICs of sparfloxacin of about one-, two-, or fourfold. Lowering of the pH from 6.39 to 5.27 in urine generally resulted in an increase in concentrations of divalent cations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of about two- or fourfold compared with those in urine at pHs from 6.84 to 8.1.

TABLE 4.

Influence of human urine on the in vitro activities of ciprofloxacin (CPFX) and sparfloxacin (SPFX) against E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853

| Subject no. | NH4Cl treatment

|

NaHCO3 treatment

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Concn [mg/liter (fold increase)] of:

|

MIC [μg/ml (fold increase)] for:

|

pH | Concn [mg/liter (fold increase)] of:

|

MIC [μg/ml (fold increase)] for:

|

|||||||||

| Ca2+ | Mg2+ |

E. coli NIHJ JC-2

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853

|

Ca2+ | Mg2+ |

E. coli NIHJ JC-2

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853

|

|||||||

| CPFX | SPFX | CPFX | SPFX | CPFX | SPFX | CPFX | SPFX | |||||||

| 1 | 5.36 | 320 (4) | 145 (4.3) | 0.25 (4) | 0.25 (4) | 0.125 | 2 (2) | 6.28 | 86 | 61 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.50 (2) | 1 |

| 2 | 5.40 | 220 (4) | 120 (1.2) | 0.125 (4) | 0.125 (4) | 0.125 (1) | 2 (4) | 6.37 | 58 | 100 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.125 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 5.27 | 200 (2) | 80 | 0.50 (8) | 0.50 (8) | 0.125 (2) | 2 (4) | 6.10 | 97 | 105 (1.3) | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.50 |

| 4 | 6.39 | 200 (2) | 135 (2.5) | 0.063 (4) | 0.063 (4) | 0.25 (2) | 0.50 (4) | 7.78 | 43 | 53 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| 5 | 6.03 | 240 (2) | 145 (1) | 0.125 (2) | 0.25 (4) | 0.125 | 2 (4) | 7.28 | 225 | 110 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.50 (4) | 0.50 |

| 6 | 6.12 | 200 (2) | 54 (1) | 0.50 (8) | 0.50 (8) | 0.25 (1) | 2 (1) | 7.14 | 13 | 44 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 7 | 6.13 | 270 (7) | 130 (1.3) | 0.125 (1) | 0.25 (1) | 0.25 (1) | 2 (1) | 7.43 | 41 | 100 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 8 | 5.79 | 80 (1) | 70 (1) | 0.125 (2) | 0.125 (2) | 0.25 | 1 (2) | 6.35 | 79 | 85 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.50 (2) | 0.50 |

| 9 | 5.30 | 56 (1) | 33 (2) | 0.50 (31) | 0.50 (31) | 0.50 (1) | 2 (4) | 8.01 | 36 | 18 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.75 (0.43) | 178.4 (97) | 101.3 (40.1) | 6.97 (0.71) | 75.3 (58.6) | 75.1 (30.5) | ||||||||

| Range | 5.27–6.39 | 56–320 | 33–145 | 0.063–0.50 | 0.063–0.50 | 0.125–0.50 | 0.50–2 | 6.84–8.1 | 13–225 | 18–110 | 0.016–0.125 | 0.016–0.25 | 0.125–0.50 | 0.125–2 |

When E. coli NIHJ JC-2 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were cultivated in pooled human urines, an additional increase in the MICs could be observed. The MICs of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin for E. coli NIHJ JC-2 at pH 8.0 in MHB with Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations of 25 and 12.5 mg/liter, respectively, were 0.016 and 0.08 μg/ml (Table 3), whereas at the same pH in urine with Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations of 36 and 18 mg/liter, respectively, they were 0.016 μg/ml (Table 4). The results indicated that low pH and the presence of urine generally increased the MICs.

DISCUSSION

One of the original objectives of this study was to investigate the impact of acidification and alkalinization of urine on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin after a single 200-mg oral dose was administered. Changes in urinary pH had no effect on ciprofloxacin absorption, distribution, or elimination. The pharmacokinetic values for ciprofloxacin in control subjects were in good agreement with those reported previously (12).

Although the various quinolones are structurally similar, they vary considerably in polarity. As an extremely polar agent, ciprofloxacin is both filtered and secreted with the result that its renal clearance values exceed the glomerular filtration rate by a factor of 2 to 3 (12). Due to its polarity, reabsorption of this agent would be expected to be minimal (20). Manipulations of the urine pH should have altered the percentage of this zwitterion antibiotic ionized, but as a quinolone with a high contribution of tubular secretion, this manipulation failed to modify the elimination of ciprofloxacin.

Preliminary data indicate that factors such as the pH and divalent cation concentration may affect drug activities (14, 17). It has been suggested that the effect of pH on the activity of fluoroquinolones against E. coli depends on the nature of the substituents at the C-7 position of the quinolone nucleus (1). Fluoroquinolones with a piperazine group at C-7 (e.g., ciprofloxacin or sparfloxacin) display a progressively decreased activity with pH reduction. Smith and Ratcliffe (18) suggest that at high pHs all of the fluoroquinolones tend to be negatively charged (it seems that negatively charged piperazine-containing drugs, including ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin, are the most active species); however, at lower pHs (e.g., in urine) the piperazine-containing fluoroquinolones are positively charged, and this factor may decrease their penetration into bacteria and thus decrease their activity. In addition to the effect of pH on the activity of fluoroquinolones, the divalent urinary cations such as calcium and, especially, magnesium may also decrease their activity (10). Whether magnesium interacts with the outer membrane as in the case with amino-DNA-gyrase-DNA complex is presently unknown (23).

From the results of this study, we conclude that urine and in particular its pH antagonizes the activity of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin. These data are in agreement with those of other investigators who described the same phenomenon (22, 23). Lowering of the pH from 6.39 to 5.27 in urine generally resulted in an increase in MICs of about 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, or 31-fold in the case of E. coli NIHJ JC-2 in a similar fashion for both drugs. In the case of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, ciprofloxacin was more active than sparfloxacin under the same conditions. This may be due to the fact that ciprofloxacin has an extremely high intrinsic bactericidal potential (22). This property of ciprofloxacin may be of importance when low drug concentrations are available in an unfavorable environment.

We conclude that the decreased activity due to pH reduction and the presence of divalent urinary cations is offset by high urinary ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin concentrations, so this negative effect would be of minor importance in most clinical situations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to K. Perparim for his helpful discussion and suggestions and to K. Ogawa for assistance in this study. We also thank Mitsubishi-Kagaku BCL and Clinical Laboratories Inc., Osaka, Japan, for their kind contribution to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard J, Gasser T, Rhodes P, Madsen P O. MICs of ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim for Escherichia coli: influence of pH, inoculum size and various body fluids. Infection. 1991;3(Suppl.):S167–S169. doi: 10.1007/BF01643691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campoli-Richards M D, Monk J P, Price A, Benfield P, Todd P A, Ward A. Ciprofloxacin. A review of its antimicrobial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1988;35:373–447. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198835040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clair C. Brief report: ciprofloxacin in the treatment of urinary tract infections caused by Pseudomonas species and organisms resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Am J Med. 1987;82(4A):288–289. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Method. Standard methods of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1990;38(1):102–105. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Method. Standard methods of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 1993;41(2):183–189. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gitelman H J. An improved automatic procedure for the determination of calcium in biological specimens. Anal Biochem. 1967;18:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamberi M, Tsutsumi K, Kotegawa T, Nakamura K, Nakano S. Determination of ciprofloxacin in plasma and urine by HPLC with ultraviolet detection. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1251–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamberi M, Kotegawa T, Tsutsumi K, Nakamura K, Nakano S. Sparfloxacin pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: the influence of acidification and alkalinization. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:633–637. doi: 10.1007/s002280050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyle V-B, David K, Guay R P, Rotschafer J C. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;19:434–461. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199019060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin C S, Smith J T. 4-Quinolones and multivalent ions. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:149. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.1.149. . (Correspondence.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann C K, Yoe J H. Spectrophotometric determination of magnesium with sodium 1-azo-2-hydroxy-3-(2,4-dimethylcarboxanilido)-naphthalene-1-(2-hydroxybenzene-5-sulfonate) Anal Chem. 1956;28:202–205. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuman M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the newer antimicrobial 4-quinolones. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1988;14:96–121. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198814020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikaido H, Thanassi D G. Penetration of lipophilic agents with multiple protonation sites into bacterial cells: tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones as examples. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1393–1399. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez-Giraldo C, Hurtado C, Moran F J, Blanco M T, Gomez-Garcia A C. The influence of magnesium on ofloxacin activity against different growth phases of Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:1021–1022. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.6.1021. . (Correspondence.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan J L, Berenson C S, Greco T P, Mangi R J, Smith M, Thorton G F, Andriole V T. Oral ciprofloxacin in resistant urinary tract infections. Am J Med. 1987;82(4A):303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadao K, Soichi A. Brief report: ciprofloxacin treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Am J Med. 1987;82(4A):301–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharon M S, Robert H K E, Charles E C. Conditions affecting the results of susceptibility testing for the quinolone compounds. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1988;34:308–314. doi: 10.1159/000238584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith J T, Ratcliffe N T. Effects of pH and magnesium on the activity of 4-quinolone antibacterials. Infection. 1986;14(Suppl. 1):31–35. doi: 10.1007/BF01645195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorgel F, Kinzig M. Pharmacokinetics of gyrase inhibitors, part 1: basic chemistry and gastrointestinal disposition. Am J Med. 1993;94(Suppl.):44S–55S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorgel F, Ulrich J, Kurt N, Ulrich S. Pharmacokinetic disposition of quinolones in human body fluids and tissues. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;16(Suppl. 1):5–24. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198900161-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wise R, Andrews J M, Edwards L J. In vitro activity of Bay 09867, a new quinolone derivative, compared with those of other antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:559–564. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.4.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeiler H J. Influence of pH and human urine on the antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and ofloxacin. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1985;XI(5):335–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhanel G G, Karlowsky J A, Davidson R J, Hoban D J. Influence of human urine on the in vitro activity and postantibiotic effect of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1991;37:218–223. doi: 10.1159/000238857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]